Global manifestations of the Israel-Palestine conflict in anti-war aesthetic images from around the world

Concern over the armed conflict unleashed on October 2023 in the area known as the Gaza Strip has led to mobilizations, takeovers of public spaces and performances around the world. Although it is part of a long-standing territorial conflict between two ethno-national groups, it has become a global concern for different student groups, religious, human rights and political activists who are speaking out against a war that has contravened international agreements and has increased hate speech and attacks on civil society - mainly children and women, the elderly and journalists.

During 2024, the war intensified and expanded its territorial radius beyond Palestine. This situation has given rise to multiple demonstrations that make use of ritualized symbolic expressions to demand a halt to the war and denounce the horrors it provokes. Pro-Palestinian committees have been formed in different cities to oppose the war and denounce what Amnesty International called genocide. On the other hand, tensions have also shifted to public spaces, which has led to police repression of protests.

Due to the importance of this topic in today's time, the magazine Encartes launched an open invitation to participate in the vi photography contest with images capturing objects, subjects, places, landscapes, symbols and aesthetics that have accompanied the mobilizations and demonstrations around the Israel-Palestine war conflict taking place in different universities, public squares, in front of embassies, in national festivities, in political and religious ceremonies and even in parades and other festivities.

The call stated that the images had to cover the following contents: to show the processes of aesthetic creativity that generate anti-war and anti-nationalist manifestations, denouncing violence, using not only words but also staging, installations and shots of emblematic sites and stylistic interventions of symbols, as well as the creation of an iconography of denunciation or the metaphoricity (deconstruction of signs of power) with which the conflicts of race, nation, ethnicity, territory, religion and gender are expressed.

The call was extended to visual artists, filmmakers, researchers, communities, collectives, students of social sciences and humanities to send their photographs accompanied by a descriptive title and caption data (emphasizing the event, the place where it took place, who are the participants and the date), and a short text explaining the expressive meanings of the demonstration.

The response was very good. We received 105 photographs from 21 participants. The photographs received document demonstrations around the Israel-Palestine conflict in nine different cities, showing the impact that this issue has had on a global scale: Guadalajara, Guanajuato, Mexico City, Tijuana, San Cristóbal de las Casas (Chiapas), Santiago de Chile, New York and Los Angeles (United States) and Uruguay. Due to the quality of the images and the strength of the situations they were able to capture with their cameras, it was not easy to make the selection and even less so to decide which ones would get the first places. Thus, we had to establish several criteria to make a selection of 17 photographs: first, we considered the quality of the photograph (framing, aesthetic composition, image resolution); second, we took into account the expressive force of the image (that in itself could generate a message); third, the members of the jury had in mind the narrative as a whole and tried to ensure that the photos chosen would allow us to form a visual narrative that would account for the diversity of situations, places and actors involved in the demonstrations. In this way we were forced to avoid repetition of content and to choose only one photograph when this happened. Five members of the editorial team participated in the selection committee.

We decided to award first place to Elizabeth Sauno's photograph, which shows a demonstrator depicting a Palestinian mother carrying a bloody baby in her arms. The photo was taken during the March for Palestine on December 17, 2023 in Mexico City. Second place was awarded to Rodolfo Ontiveros for the photograph "Fences" which generates the metaphor of the body as a territory lacerated by barbed wire; it was taken on September 5, 2024, during a demonstration on Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City. We decided to award third place to two photographs: one by Charlie Eherman and the other by José Manuel Martín Pérez. The first author's depicts "Two men, a Palestinian (left) and an Orthodox Jew (right), show peace signs next to the White House in Washington D. C., USA, during a national demonstration" (June 8, 2024, Washington). The second photograph presents how the global action of solidarity with Palestine is articulated with the feminist demands that took place in the already named Plaza de la Resistencia in San Cristóbal de las Casas during the march of March 8, 2024, in the framework of International Women's Day.

Each of the four winning photographs documents a different face of the demonstrations, but, when seen together, they allow us to recognize that the shared symbols give a single voice to people of different nationalities who may not speak the same language. At the same time, they help us to recognize how their installation in different places deploys multiple enunciations, making photography a resource of metaphoricity as a productive matrix to redefine the social (Bhabha, 2011) from the pro-Palestinian demonstrations and against the war actions in the Gaza Strip.

The idea behind the photographic contests organized by Encartes seeks to assemble the images in order to generate a meta-narrative. Each image captures a different local scenario that, when put in relation, allows the narration of different realities articulated by a global aesthetic. These are articulated because they occur in the simultaneity of a historical time even though they are replicated in multiple distant places. At the same time, the singularity of each shot accounts for the multiplicity of actors, scenarios and symbolic expressions that are manifested there. The exercise allows us to circumvent the paradox of political homogeneity and heterogeneity of identity belonging.

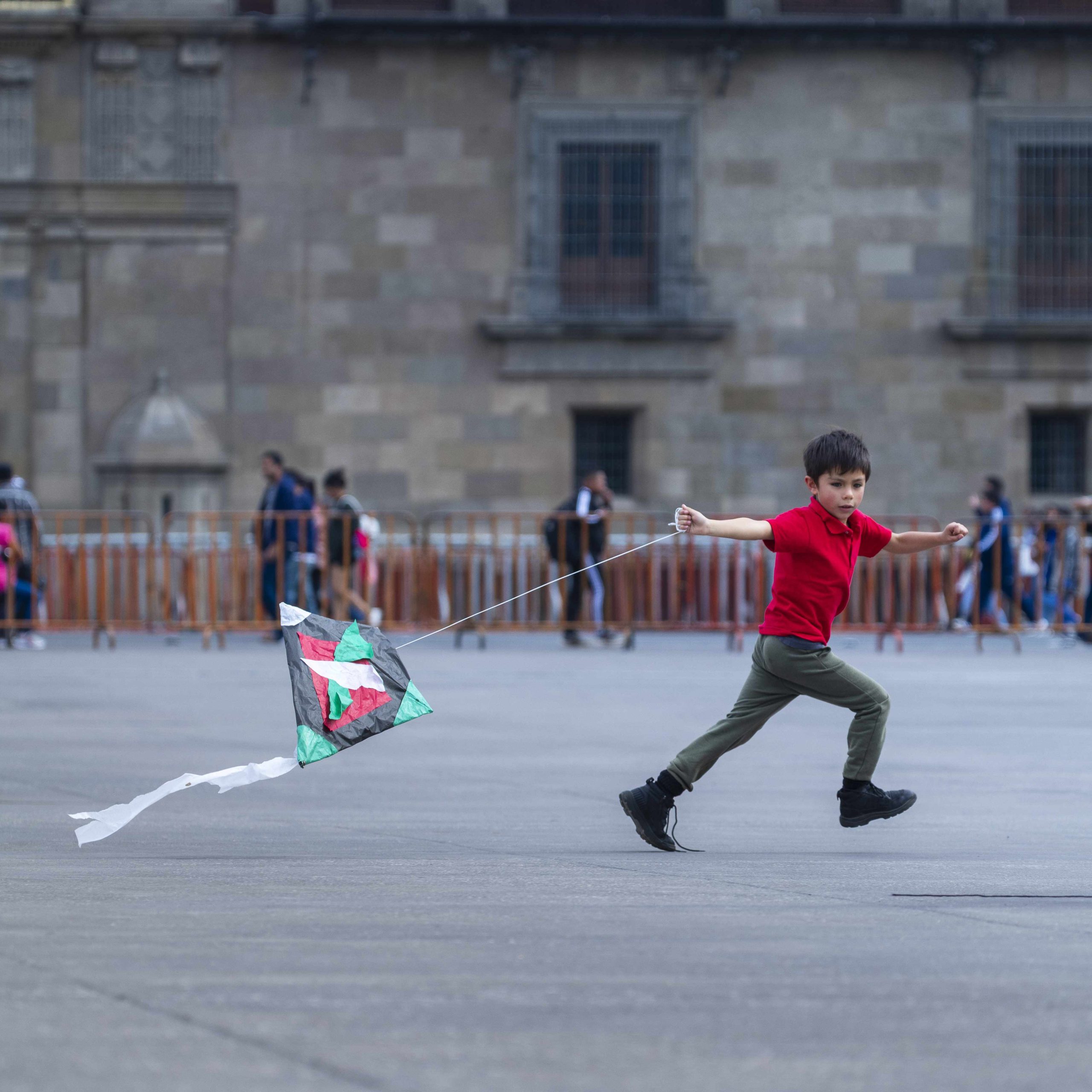

The pro-Palestine movement is undoubtedly a transnational mobilization that has produced its own slogans and symbolism. These aesthetic marks and emblems are the lingua franca that articulates a global communitas of an imagined moral community that shares values, although they will never meet or interact face to face (Anderson, 1993); that has in common a sense of grievance and at the same time a sense of commitment. Different pro-Palestinian committees exist in different countries, cities and towns. The slogans of denunciation and symbols are shared representations and build a single voice in simultaneous time throughout the world. For example, kite flying is already an act of empathy with the children of the Palestinian people; the use or representation of the kufiya covering head and neck is already a distinctive element of the Middle East and wearing it places the enunciation of an activist body. The watermelons, whose colors match the Palestinian flag, go hand in hand with the choruses and banners of free Palestine, as do the Palestinian flags.

The interesting thing about representation is that these symbols do not appear in a vacuum: they dress bodies, they are installed in key scenarios to intervene places. The symbols have acquired a powerful metaphoricity with dissident force. For example, the kite reaches its flight in the emblematic building of the National Autonomous University of Mexico or flying over the concrete slab of Mexico City's zocalo (photo by Dzilam Méndez Villagrán). The flag is placed on the sand of a beach, metaphorically restoring the slogan "From the river to the sea" (photo by Pilar Aranda). The flag is intervened with the phrase "Nunca más, nunca nadie" and "ni un@ más" by a Jewish population that places the slogan of opposition to the holocaust on the Palestinian flag, to generate a hybrid of opposition to the war and to dissociate itself from Zionism (photos by Charlie Eherman).

The flag is used to conquer territories. Its placement constitutes representativeness in a regime of unrepresentability (Rancière, 2009). In the different photos selected, the flag generates a regime of visibility of solidarity for Palestine that, when placed in iconic places such as monuments, acquires a metaphorical enunciative power: In front of the Angel of Independence on Reforma Avenue in Mexico City (photo by Elizabeth Sauna), in front of the Glorieta de la Minerva (symbol of justice) in Guadalajara (photo by Christophe Alberto Palomera Lamas), placed on the border wall that divides Mexico and the United States today in what used to be the same territory inhabited by families that were divided by the wall (photo by Marco Vinicio Morales Muñoz). It even extends the enunciation of genocide to other realities, as is the case with the placement of the sign "Stop genocide" on the wall that divides Mexico from the United States (photo by Priscilla Alexa Macías Mojica), extending the clamor to the tightening of immigration policies. Symbols also move to occupy spaces and change their vocation, such as the emblematic Central Station in New York, taken over by demonstrators from the Jewish community (photo by Charlie Eherman); or their presence in the plaza of San Cristobal de las Casas (photo by Jose Manuel Martin Perez) with a wooden cross in the background, representing the indigenous Catholicism of the area.

The flag transgresses territorialities that also leave their territories traced by the States to configure mini-domains in other countries. This is the case of embassies. The photographs of a demonstration outside the Israeli embassy reproduce scenarios and experiences of violent confrontation (photo by Gerardo Vieyra). We see homemade bombs, police fences, fire, fallen bodies. This did not happen in Gaza, but in Mexico, in the territory of the Israeli embassy; but also in the center of Mexico City, in front of the Guardiola building, which houses the Bank of Mexico (photo by Ana Rodríguez). Territories are made by practicing them and the doors of the Guadalajara International Book Fair during the last month of November acquire the notoriety of an international forum and, therefore, of visibility beyond the local (photo by Pilar Aranda).

Symbols linked to different bodies also generate intersections between various activisms: they gain and expand the demands when they are linked to the feminist movement or when they are articulated with the demands for the recognition of transsexuals; or the resymbolization achieved by placing the already recognized mustache of Hitler, the exterminator of the Jews, on the portrait of Benjamin Netanyahu, current Prime Minister of Israel.

We invite you to sharpen your gaze to read the multiple realities generated by the aesthetic interventions in favor of Palestine captured by the lenses of photographic cameras and, at the same time, to allow yourself to enjoy the marvelous photos that make up this visual essay.

Renée de la Torre

March for Palestine 17 Dec 2023 CDMX

Elizabeth Sauno, Mexico City, December 17, 2023.

Mobilization in solidarity with Palestine, from the Angel of Independence to the Zocalo, Mexico City.

Fences

Rodolfo Oliveros, Paseo de la Reforma, CDMX, September 5, 2024.

Two young men march through Palestine holding hands; the body is the territory encircled by the State of Israel.

One year of genocide, 76 years of occupation.

José Manuel Martín Pérez, Plaza de la Resistencia, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico, March 8, 2024.

On March 8, in the framework of International Women's Day, the feminist movement in Chiapas joined the global action in solidarity with Palestine.

Symbols of peace in the capital.

Charlie Ehrman, Washington DC, June 8, 2024

Two men, a Palestinian (left) and an Orthodox Jew (right), display peace signs next to the White House in Washington DC, USA, during a national demonstration.

Pro-Palestinian Minerva

Christophe Alberto Palomera Lamas, Mobilization in solidarity with Palestine. Glorieta la Minerva, Guadalajara, Jalisco. Committee of Solidarity with Palestine GDL. November 12, 2023.

La Minerva, an emblematic symbol of Guadalajara, has been a meeting point to celebrate the identity of Guadalajara, but also to protest. Spectator of the search for justice and strength gives opening to the first mobilizations of the Committee of Solidarity with Palestine GDL. November 12, 2023.

Boy with kite in the Zócalo square

Dzilam Méndez Villagrán, Mexico City Zócalo, January 14, 2024.

A symbolic act to express support for the children of Gaza through the making of kites, held in the Zócalo square in Mexico City.

A light for Palestine

Sandra Suaste Avila, Mexico City, November 5, 2023.

A group of academics and activists demonstrate and offer cempasúchil flowers, candles, bread and the wish for an end to the violence in the Gaza Strip. Mexican women remember Palestinian women.

Stop genocide

Priscila Alexa Macías Mojica, Tijuana, Baja California, June 1, 2024.

Poster placed on the U.S.-Mexico border fence in a cross-border art and community activity.

Global action for Rafah in Mexico

Gerardo Vieyra, Mexico City, May 28, 2024.

On Tuesday, May 28, 2024, students from various universities and social organizations in support of Palestine, demonstrated outside the Israeli Embassy in Mexico City, in rejection of the Israeli attacks that arrived that day to the center of Rafah, south of the Gaza Strip, the same day that Ireland, Spain and Norway recognized the State of Palestine and despite international condemnation for a bombing of a camp for displaced persons. According to data from human rights organizations, more than 46,000 people have died in Palestine and a large number of people have been wounded with serious health repercussions.

Looking down on the resistance from the 10th floor.

María Fernanda López López, UNAM Ciudad Universitaria, Mexico City, May 2024.

View of the encampment and monumental painting written on the esplanade of the central library of the UNAM, carried out by the members of the university student encampment in support of Palestine.

A break at Grand Central, no more war.

Charlie Ehrman, Manhattan, New York, October 27, 2023.

Hundreds of demonstrators from the Jewish Voice for Peace organization occupied the concourse of Grand Central Station in Manhattan, New York, to stop passenger traffic and demonstrate for a cease-fire in the conflict between Israel and Hamas.

March 8M CDMX

Elizabeth Sauno, Mexico City, March 8, 2024.

During the March 8 march in Mexico City, there were contingents in solidarity with Palestine, where sexual dissidents showed their support for the Palestinian cause.

Day of the Dead CDMX 30 Oct 2024.

Elizabeth Sauno, October 30, 2024, Mexico City.

As part of the Day of the Dead, journalists gathered at the Angel of Independence to make visible the journalists who have lost their lives in the coverage of Israel's military escalation against the Palestinian people.

Stop genocide, a collective cry.

Ana Ivonne Rodríguez Anchondo, Mexico City, May 15, 2024.

Youth in front of police blockade at the Guardiola building, during the demonstrations for the 76th anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba, in Mexico City.

Handala in the corner of the world.

Marco Vinicio Morales Muñoz, Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico, February 13, 2025.

Handala, a symbol of the Palestinian people, is depicted on the Tijuana border wall along with other aesthetic elements and anti-war graphic designs that refer to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Censorship in the media and shouting in the streets

Ilze Nava, Zócalo de la CDMX, February 17, 2024.

Demonstration for Free Palestine 2024.

Journalists at FIL

Pilar Aranda, Expo, Guadalajara (FIL), December 5, 2024.

On the occasion of the XX International Meeting of Journalists, a protest was held in the vicinity of the International Book Fair in Guadalajara, it is reported that in the "conflict" there are close to 200 journalists murdered.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict (1993). Imagined communities. Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism.. Mexico: FCE.

Bhabha, Homi K (2011). The place of culture. Buenos Aires: Spring.

Rancière, Jacques (2009). The distribution of the sensitive. Santiago de Chile: lom.

El monocultivo y el “ecuaro”: Aspectos y genealogías de la modernización agrícola en San Miguel Zapotitlán, México

Rubén Díaz Ramírez

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana – Unidad Iztapalapa, México

es doctor en Antropología Social por la Universidad Iberoamericana. Actualmente realiza una investigación postdoctoral en la UAM-Iztapalapa. En su trayectoria académica se ha dedicado a la investigación histórica y etnográfica sobre diversos aspectos de las transformaciones sociotécnicas, así como los imaginarios del progreso, la modernización y el desarrollo en varias localidades del municipio de Poncitlán, Jalisco. Su trabajo actual versa sobre la antropología e historia tecno-ambiental de Poncitlán, con énfasis en San Miguel Zapotitlán.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4424-0001

Imagen 1. Fantasmas y ruinas del progreso

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 16 de enero de 2022.

(Mariana en el viejo tractor Oliver del ejido) La agricultura es un modo de vida en la que los fantasmas y ruinas de los proyectos del pasado perviven visibles e invisibles, apacibles y violentos, efímeros y perdurables. Este modelo de tractor Oliver fue una de las insignias de la “modernización” de la agricultura ejidal en la década de 1950. En sus ruinas jugaron los niños de la generación nacida en la década de 1980.

Imagen 2. Resignificación de las infraestructuras del progreso

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 07 de marzo de 2022.

(Antiguas oficinas de CONASUPO, ahora Castariz) Una de las funciones de CONASUPO fue evitar los abusos de los intermediarios (conocidos como coyotes) en la comercialización del maíz. En el paisaje rural mexicano abundan estas ruinas que se asemejan a los templos mesoamericanos. En la Imagen 2 aparecen las bodegas de San Miguel Zapotitlán. El ejido renta las bodegas a Agropecuaria Castariz y a Integradora Arca, que se apropiaron simbólica y funcionalmente de las materializaciones de los sueños del progreso de la agricultura mexicana del siglo XX.

Imagen 3. Presencias no humanas residuales

Potrero Barranquillas, 07 de mayo de 2021.

(Datura floreciendo en un callejón cerca del trigo) Sujetar la agricultura a las cadenas productivas de la industria a mediados del siglo XX resultó no solo en el sometimiento de los campesinos a la producción de alimentos para el mercado urbano, también produjo el desplazamiento o aniquilación de otras especies clasificadas como “malezas” o “plagas”. Los callejones (áreas entre parcelas) son espacios residuales, albergan especies que también son residuales y por ello sobreviven a los agroquímicos. En la Imagen 3, una planta de toloache común, quizás Datura stramonium L.

Imagen 4. Visitantes inesperados

Potrero Barranquillas, 06 de diciembre de 2018.

(“Avenilla” en el callejón) Historias de seres vivientes perviven en el paisaje. Así como un día los castellanos trajeron sus especies del otro lado del océano, en el siglo XX se introdujeron maíces híbridos, sorgos y variedades de trigo exógenas. Los caminos quedaron trazados para el arribo de otras especies inesperadas. Por ejemplo, la “avenilla” (posiblemente Themeda quadrivalvis), que coloniza áreas perturbadas en cerros y carreteras, es un indicio de su trasiego encima de la maquinaria agrícola.

Imagen 5. El trigo: regar con agua contaminada del río Santiago

Potrero Barranquillas, 11 de enero de 2023.

(Riego “rodado” con agua del río) Los sistemas de riego son infraestructuras que conjuntan tiempos. En el siglo XIX, pequeños propietarios y hacendados acapararon las tierras de riego, pero los campesinos ganaron su derecho al agua en la reforma agraria del siglo XX. Estos sistemas aprovechan zanjas, canales, bordos y represas, algunas provienen de la época de las haciendas, otras fueron abiertas en los años de la reforma agraria.

Imagen 6. El trigo entre tradición e industria

Potrero Barranquillas, 21 de enero de 2023.

(La “raya” para guiar el agua por la parcela) Los agricultores y regadores son unos expertos en ver el terreno y usar la gravedad para dirigir las aguas dentro de las parcelas para regar el trigo. Este conocimiento se transmite a través de las generaciones. El líquido para el riego se extrae o se canaliza desde el río Santiago, en cuyo cauce las empresas del corredor industrial desechan sus residuos tóxicos. Como se observa, la “naturaleza” y la agricultura están contenidas por la tradición y por la industria de maneras poco evidentes.

Imagen 7. Dependencia: el monocultivo y los fertilizantes químicos

Potrero Barranquillas, 23 de febrero de 2021.

(Los dos Martín entre costales de urea). La agricultura comercial depende de los fertilizantes químicos. Entre 2021 y 2022 el precio de la urea alcanzó en la región hasta los 24 000 pesos por tonelada; 18 000 pesos según otras fuentes (Index Mundi 2023). La situación se agravó por la escasez provocada por la guerra entre Rusia y Ucrania, iniciada el 24 de febrero de 2022.

Imagen 8. Una dupla esencial: el monocultivo y el nitrógeno

Bodega Libertad, San José de Ornelas, 10 de junio de 2023.

(Sulfato de amonio y tarimas de Monsanto) El desabasto de urea y la guerra Rusia-Ucrania provocaron aumentos en el precio de la urea y por tanto en los gastos de producción por hectárea del maíz, 5 o 10 000 pesos más que en años anteriores. En una charla entre agricultores escuché: Estados Unidos nos lleva “muchísima ventaja” porque allá ya existen las sembradoras y los aplicadores de fertilizante que dosifican la cantidad suficiente por metro cuadrado. En México, al contrario, se “tira parejo”. Por eso, “las tierras que no lo necesitan se vuelven mejores y las que lo necesitan peores porque no reciben el fertilizante necesario” (Diario de campo, 29 de mayo de 2022).

Imagen 9. Cuando se alteran los ensamblajes

La Constancia, Zapotlán del Rey, 27 de marzo de 2021.

(Agricultores ven pasar una patrulla) El 22 de marzo de 2021, Día Mundial del Agua, los policías estatales destruyeron equipos de arranque del sistema de bombeo de varios de los ejidos de la región y retrasaron el riego en una etapa crítica del ciclo del trigo. Con estas acciones el gobernador de Jalisco, Enrique Alfaro, responsabilizó a los agricultores de la crisis de abastecimiento de agua potable que sufría la ciudad de Guadalajara e intentó granjearse la simpatía de sus gobernados con el típico recurso de enfrentar el campo con la ciudad.

Imagen 10. Cuando se alteran los ensamblajes

La Constancia, Zapotlán del Rey, 27 de marzo de 2021.

(Agricultores organizados) Los agricultores buscaron el diálogo con el gobierno. Al final, se acordó que se restaurarían los equipos, pero las afectaciones ya estaban hechas. Las cosechas fueron de dos a tres toneladas por hectárea, la mitad o menos del promedio en años normales. El precio del trigo fue de 4 500 pesos la tonelada. Los ingresos de nueve mil pesos, en el caso de cosechas de dos toneladas por hectárea, son insuficientes, ni siquiera cubren la mitad de los gastos de producción.

Imagen 11. El agave

Potrero Barranquillas, 15 de septiembre de 2022.

(Nuevos cultivos en el ejido) La sequía, las acciones del gobierno estatal, los altos precios de insumos agrícolas y la expansión del mercado del tequila orillaron a varios agricultores a rentar sus parcelas a productores de agave (tequilana Weber). La fiebre por el agave surge en parte por el alto precio que alcanzó durante el periodo 2019-2021. Según una nota del periódico en línea UDG TV, “el precio del kilogramo del agave […] superó los 30 pesos, [30 veces más caro] que en 2006 cuando se vendía en 1 peso” (García Solís, 2020). En 2024, el precio varía entre 15 y 8 pesos el kilogramo.

Imagen 12. Eliminar especies sin valor

Potrero Barranquillas, 21 de febrero de 2019.

(Preparación del tanque de fumigación para el trigo) El monocultivo implica la eliminación sistemática de cualquier especie animal o vegetal que “compite” por espacios y recursos con las plantas cultivadas. Como apunta Gilles Clément, “la erradicación de una especie invasiva es siempre un fracaso: es afirmar que el estado actual de nuestros conocimientos no nos permite otro recurso que la violencia” (2021: 19). Uno de los herbicidas post emergentes más usados en San Miguel Zapotitlán se llama Ojiva (Paraquat), una prueba más del vocabulario bélico que pervive en la agricultura (Romero, 2022:51).

Imagen 13. La cosecha

Potrero Barranquillas, 19 de mayo de 2021.

(Los rastros verdes de otras especies entre el trigo) El trigo se cosecha a mediados de mayo. Este cereal fue la insignia de las haciendas de la región hasta la Revolución Mexicana de 1910 y se convirtió en el centro de atención de la ciencia agronómica a partir de 1940 (Olsson, 2017: 150). Variedades de trigo mexicanos se exportaron a países tan distantes como India, con lo que se crean más corredores globales biotecnológicos.

Imagen 14. Las máquinas

Potrero Barranquillas 19 de mayo de 2021.

(Cosechadora cargando trigo en el camión Dina) Uno de los símbolos visibles de la modernización agraria en esta región son las máquinas. Desde la década de 1960 el trabajo en los ejidos de Poncitlán es inimaginable sin trilladoras, tractores y camiones de carga. Los camiones transportan los granos hasta las fábricas Barcel, Kellogg´s, Bimbo, Ingredion, Cargill o PEPSICO, donde transforman los cereales en productos industriales que después regresan en camiones repartidores a los comercios en donde los agricultores los compran en forma de mercancía.

Imagen 15. Pagar la maquila

Potrero Barranquillas, 11 de junio de 2021.

(Pagar a tiempo la maquila) A mediados de la década de 1980 los ejidatarios compraron maquinaria agrícola para uso individual. Por diversas razones, estos agricultores fueron perdiendo su maquinaria hasta depender de los maquiladores: dueños de tractores, sembradoras, cosechadoras y demás equipo que rentan sus servicios a quienes los requieran. Esta es otra de las razones por las que el minifundio se encuentra en retroceso.

Imagen 16. De maíz mesoamericano a semilla híbrida

Potrero Barranquillas, 11 de junio de 2021.

(Jornalero revisando la semilla híbrida de maíz) Hay algo inquietante en el hecho de que las compañías privadas que comercializan semillas híbridas de maíz sean dueñas de “miles de años de conocimientos acumulados por millones de productores” que han sido depositados en la semilla como “plasma germinal” (Warman, 2003: 185). Los agricultores de Poncitlán dependen de estas empresas para comprar semilla año con año desde mediados del siglo XX. En ese entonces, a los híbridos les llamaban “maíz del gobierno” (Diario de campo, 25 de junio de 2022).

Imagen 17. La siembra genera tensión

Potrero Barranquillas, 10 de junio de 2023.

(Los agricultores supervisan la siembra correcta del maíz) La siembra del maíz inicia a finales de mayo, cuando han caído las primeras lluvias. La siembra genera tensiones nerviosas en los agricultores porque, como me comentó uno de ellos: “Tenemos tirado el dinero en las parcelas”. La inversión para producir maíz en 2018 se encontraba entre los 20 y 30 000 pesos por hectárea (Diario de campo, 2 de junio de 2018). Durante el 2023 la inversión fue de alrededor de 40 000 pesos por hectárea.

Imagen 18. La siembra a la hora que sea necesaria

Potrero Barranquillas, 10 de junio de 2023.

(Noche de siembra del maíz) Hay que mirar al cielo en busca de los indicios del clima. En 2022 una serie de tormentas reblandecieron los suelos del ejido, luego paró de llover hasta bien entrado el mes de junio. La lluvia ocasionó el retraso de las siembras y la resequedad marchitó las plantas que nacieron para encontrarse expuestas bajo un sol inclemente con apenas algo de humedad. Por eso, la siembra se realiza a la hora que sea necesaria, incluso por la noche, porque es imperativo bregar entre los cambios climáticos.

Imagen 19. Eliminar la competencia del maíz

Potrero Barranquillas, 22 de junio de 2022.

(Los jornaleros rellenan las bombas de aspersión) Los jornaleros están en contacto directo con los pesticidas. Según un estudio, cada año en el mundo 385 millones de personas enferman por envenenamiento con plaguicidas (Chemnitz et al., 2022: 18). Pero los efectos de los pesticidas en la salud humana alcanzan incluso a los consumidores urbanos de frutas y verduras contaminados por residuos invisibles.

Imagen 20. Quemar

Potrero Barranquillas, 22 de junio de 2022.

(Los jornaleros eliminan el “mostrenco”) Se le llama “mostrenco” a la milpa que nace de los granos de maíz que no alcanzan a ser recolectados por las máquinas cosechadoras. Es una planta rebelde que germina donde no debería: afuera de las líneas de los surcos. A la labor de eliminar el mostrenco y otras malezas los agricultores la llaman “quemar”, porque cuando el herbicida actúa sobre las plantas las seca, coloreándolas de dorado, amarillo o blanco. Un cultivador preguntó a un ingeniero por qué la ciencia no ha inventado un agroquímico que acabe de manera definitiva con este problema, a lo cual el ingeniero respondió entre veras y bromas: “¿Si acabamos con eso, qué veneno les vamos a vender?” (Diario de campo, 18 de octubre de 2018).

Imagen 21. Mirar la siembra

Potrero Barranquillas, 31 de octubre de 2018.

(Arriba, para mirar mejor las parcelas) La agricultura implica mirar. Lo anterior significa andar por la superficie de la parcela, levantar el polvo, auscultar por surcos mal alineados, sacar plantas agonizantes a la superficie, arrancar la maleza, ensanchar un canal con una pala; sentirse triste por las plantas nonatas. Ya que este mirar es una forma de conocer el mundo, “moviéndolo, explorándolo, atendiéndolo, siempre alerta al signo por el cual se revela” (Ingold, 2000: 55). El cultivo “moderno” depende de estas intuiciones “tradicionales” y sensibles.

Imagen 22. El acto de mirar en agricultura

Potrero Barranquillas, 21 de febrero de 2019.

(Mirar el trigo) El acto de mirar en la agricultura de San Miguel Zapotitlán es una búsqueda por signos de malos enredos de las múltiples especies y sus temporalidades. El agricultor observa entre las raíces y las hojas: Si el color es amarillento, es necesario fertilizar. Si las hojas están como mordisqueadas, es a causa de los gusanos. Está atento al desarrollo de hongos, mayates o gusanos cogolleros. Se siente satisfecho cuando la mayoría de las plantas refulgen con un verde oscuro y la población de plantas en la parcela luce homogénea. ¿Cuán distinto es el observar de los modernos urbanos al de los agricultores y campesinos?

Imagen 23. Colapso temporal: teocintle y maíz

Potrero Barranquillas, 22 de junio de 2022.

(Teocintle entre maíz híbrido) La lógica de la modernización supone que eficientes variedades de maíz sustituirán a las antiguas menos productivas. El teocintle, el ancestro evolutivo del maíz, crece entre los híbridos modernos en las tierras ejidales. Esta “rémora” de la evolución resiste los herbicidas y es visible solo cuando sobresalen sus espigas encima del maíz debido a su mayor longitud, que es cuando los agricultores arrancan la planta. El teocintle se ha mezclado con híbridos como el Pioneer (Inzunza, 2013: 72).

Imagen 24. Agricultores crono-nautas

Potrero Barranquillas, 19 de diciembre de 2021.

(Cosechadora vaciando el grano en un camión) Elegir cuándo sembrar y cosechar es una decisión delicada que depende de las condiciones climáticas. Si siembran antes del inicio del temporal, la semilla no nace. Si esperan demasiado, el terreno está tan blando que es imposible sembrar. Si el maíz no se seca a tiempo, las lluvias de invierno podrían dificultar la cosecha. El agricultor se convierte en un crono-nauta que navega entre temporalidades insumisas, las cuales se agitan en el Antropoceno y la Era de las Plantaciones.

Imagen 25. Las viejas nuevas demostraciones

Potrero La Bueyera, 09 de octubre de 2018.

(Registro para asistir a una demostración) Las demostraciones son las viejas tácticas del extensionismo y la comunicación rural del siglo XX. Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial existió una “necesidad” por incrementar la producción de comida en América, “la consecuencia fue un fuerte interés en los medios de comunicación”. En ese contexto, “la persuasión fue considerada el arma correcta” para incentivar el cambio y “facilitar el desarrollo” del campo (Díaz Bordenave, 1976: 136).

Imagen 26. Demostrar para vender

Potrero San Juanico, 18 de octubre de 2018.

(Ingeniero demostrando el llenado de la mazorca) Al contrario del mirar del agricultor, las demostraciones son un despliegue de retórica visual que busca convencer al productor agrícola de comprar un producto o un servicio. Los ingenieros agrónomos (antes los extensionistas) son los actores que intentan superar el supuesto “escepticismo” de la gente de campo mediante tácticas fundamentadas en la ciencia de la comunicación.

Imagen 27. Etiquetas para reconocer el híbrido

Potrero San Juanico, 18 de octubre de 2018.

(Ingeniero bromea con agricultores) Las agro empresas llaman “vitrinas” a estas escenas donde se demuestra al agricultor los beneficios de sus productos (Diario de campo, 15 de marzo de 2024). Son fundamentales los apoyos visuales, como este letrero que indica la variedad sembrada: Pioneer P3026W, que está asociada con el insecticida Dermacor de DuPont.

Imagen 28. La sociabilidad de los agricultores y la publicidad

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 04 de noviembre de 2022.

(Comida de agradecimiento) Desde 2019, Integradora Arca organiza la Expo Foro Maíz Amarillo en San Miguel Zapotitlán el mes de noviembre, una feria que vincula a los agricultores con agronegocios, aseguradoras, empresas financieras y con el sector industrial. Como el nombre lo indica, gira en torno a las complejidades de la producción de maíz amarillo para consumo de la industria. Luego de conferencias y demostraciones, Integradora Arca ofrece una comida a los asistentes, donde sobresalen los vistosos artículos promocionales de las empresas, como las gorras blanquiazules de Financiera Rural (FIRA).

Imagen 29. Nuevas tecnologías

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 04 de noviembre de 2022

(Venta de drones agrícolas) En el sector del agronegocio pervive el determinismo tecnológico: se asume que las nuevas tecnologías incrementan casi de inmediato la producción. En la Imagen 29 aparece la última innovación: el dron fumigador. Otro aparato de uso militar que extiende sus aplicaciones al agro y que se suma a la lista del maquinismo promovido por la visión futurista del agronegocio (Marez, 2016).

Imagen 30. La religiosidad del tractor

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 20 de septiembre de 2023.

(Entrada de Gremios San Miguel Zapotitlán) Si bien la agricultura es una actividad comercial abismada entre el pasado y el futuro, esto no significa que los aspectos religiosos estén ausentes en su operación. Las misas por el buen temporal y las peticiones a san Isidro Labrador, patrono de los labradores, son comunes en San Miguel Zapotitlán. La religión es parte integral de la producción de granos para la industria “moderna”.

Imagen 31. La religiosidad del agroquímico

Poncitlán, 09 de octubre de 2018.

(Entrada de Gremios Poncitlán) La iconografía agrícola traspasa los dominios para formar parte de desfiles y procesiones religiosas. En la Imagen 31 aparece un envase gigante de un agroquímico encima de un carro alegórico que desfiló en la “Entrada de Gremios”, un desfile que abre la fiesta de la Virgen del Rosario en Poncitlán, la cabecera municipal. La agricultura no es solo producción, también es cultura visual mezclada con religión.

Imagen 32: Los ecuaros: policultivos en el olvido

Cerro el Venadito, San Miguel Zapotitlán, 22 de marzo de 2023.

(Ecuaros en laderas) La agricultura comercial convive con una práctica de policultivo llamada “ecuaro”. Un campesino define ecuaro como “un pedacito de tierra para sembrar verduras o maíz, como decir: nomás pa´ los elotes” (Diario de campo, 6 de marzo de 2019). Esta práctica está a punto de desaparecer, si bien todavía quedan unos cuantos campesinos que cultivan sus ecuaros. En la Imagen 32, se observa un ecuaro en temporada de secano y en lontananza las planicies con trigo.

Imagen 33. La diversidad incluso en la sequía

Cerro el Venadito, San Miguel Zapotitlán, 22 de marzo de 2023.

(Ecuaro del tío Conrado) Los campesinos eran hacedores expertos de arreglos multiespecie antes del monocultivo. Los ecuaros han sido caracterizados como “sistemas agroforestales” donde coexisten “un elevado número de plantas perennes y anuales, silvestres y domesticadas, [así como] especies con diferentes usos” (Moreno-Calles et al., 2016: 5). En esto, los policultivos son distintos a los monocultivos, donde se asegura la supervivencia del trigo y del maíz, pero no de otras especies. En la Imagen 33 se observa la cerca viva formada por especies maderables y frutales.

Imagen 34. Ecuaro y desmonte

Cerro el Venadito, San Miguel Zapotitlán, 22 de marzo de 2023.

Antes de sembrar la milpa, el campesino “limpia” el terreno. Corta las especies consideradas malezas, mientras que tolera otras plantas útiles, con esta acción crea el paisaje a partir de la biodiversidad existente. En la Imagen 34 se observa el nopal, llamado blanco, que es muy valorado en la cocina local por su sabor y textura.

Imagen 35. Nuevos campesinos

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 16 de junio de 2022.

(Mariana sembrando un nuevo ecuaro) La pandemia publicitó el “retorno a la naturaleza” a nivel del discurso popular. Sin embargo, este fenómeno es relativamente común en las sociedades postindustriales en que los “neo campesinos” y los “neo artesanos” reivindican saberes y praxis locales al regresar al mundo rural desde las urbes (Chevalier, 1998:176). En la Imagen 34, Mariana tapa los hoyos –ahoyados con una herramienta manual llamada azadón– en donde depositó las semillas con esperanza de la cosecha.

Imagen 36. Antiguas y nuevas asociaciones

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 24 de agosto de 2023.

(Asociación de maíz, zinnias, calabazas y frijol) Los nuevos campesinos aprenden a cultivar la milpa atendiendo las enseñanzas de los antiguos campesinos, pero también mediante videos de YouTube, que fueron filmados por personas que practican la permacultura en Chile o en España. De modo que la milpa se convierte en un laboratorio de experimentación –como lo ha sido durante milenios– donde se ensamblan nuevas asociaciones entre seres vivientes y se trazan rumbos globales que son distintos a los del monocultivo.

Imagen 37. Selección emotiva de la semilla

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 09 de marzo de 2024.

(Mariana seleccionando la semilla) Las semillas que se siembran en la agricultura de ecuaros han sido seleccionadas por campesinos desde hace decenas de años. Su historia-genética es razón suficiente para promover su cuidado. Incluso en medio de esta región donde la agricultura es cada día más tecnificada y comercial, las personas conservan variedades locales de semillas de frijol, calabaza y maíz, y las plantan en donde encuentran suelo disponible. Este modo popular de conservación de semillas podría asegurar la preservación de los maíces nativos.

Imagen 38. La milpa más allá del rendimiento

San Miguel Zapotitlán, 09 de marzo de 2024.

(Calabaza y sus semillas junto a mazorcas multicolor) Una pregunta esencial de la historia económica agraria es si la milpa es productiva. Si se compara la cosecha de los ecuaros con el rendimiento de los monocultivos, la respuesta es negativa. El monocultivo está diseñado para producir masivas cantidades de materia prima para la industria. En comparación, ni siquiera hay cifras exactas sobre la producción en los ecuaros. Pero lo que se pierde en cantidad con los policultivos, se gana en diversidad y salubridad: el sabor de las calabazas o los elotes sin pesticidas es inmejorable. Y las relaciones entre humanos y no humanos se intensifican alrededor del cultivar y compartir estos alimentos.

Bibliografía:

Chemnitz, Christine, Katrin Wenz y Susan Haffman (2022), Pestizidatlas. Daten und Fakten zu Giften in der Landwirstschaft, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung; Bund. Friends of The Earth Germany; PAN Germany; Le Monde Diplomatique. Recuperado de: www.boell.de/pestizidatlas.

Chevalier, Michel (1993). “Neo-rural phenomena”, en L’Espace géographique. Espaces, modes d´emploi, número especial, pp. 175-191. Recuperado de: https://www.persee.fr/doc/spgeo_0046-2497_1993_hos_1_1_3201

Clément, Gilles (2021). El jardín en movimiento. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

Díaz Bordenave, Juan (1976). “Communication of Agricultural Innovations in Latin America.

The Need for New Materials”, en Communication Research, vol. 3, núm. 2, pp. 135-154.

García Solís, Georgina Iliana (8 de mayo de 2020). Sin desabasto, el agave azul se encarece en 3 mil%. UDG TV. Recuperado de: https://udgtv.com/noticias/sin-desabasto-el-agave-azul-se-encarece-en-3-mil-/168584

Index Mundi (2024). Urea precio mensual. Peso mexicano por tonelada. Recuperado de: https://www.indexmundi.com/es/precios-de-mercado/?mercancia=urea&meses=60&moneda=mxn

Ingold, Tim (2000). The Perception of the Environment. Essays on Livehood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

Inzunza Mascareño, Fausto R. (2013). “Hibridación entre teocintle y maíz en la Ciénega, Jal., México: propuesta narrativa del proceso evolutivo”, en Revista de Geografía Agrícola, núm. 50-51, pp. 71-97.

Marez, Curtis (2016). Farm Worker Futurism. Speculative Technologies of Resistance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Olsson, Tore (2017). Agrarian Crossings. Reformers and the Remaking of the US and Mexican Countryside. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Romero, Adam (2022). Economic Poisoning. Industrial Waste and the Chemicalization of American Agriculture. Oakland: University of California Press.

Warman, Arturo (2003). Corn and Capitalism. How Botanical Bastard Grew to Global Dominance. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Photographing a Ritual Process: An Approach to the Agency of Xantolo Masks

Pablo Uriel Mancilla Reyna

The College of San Luis

is a doctoral candidate in the Anthropological Studies Program at El Colegio de San Luis. His research interests are ritual, visual anthropology, religious practices and the anthropology of art. She is part of the Visual Anthropology Laboratory of El Colegio de San Luis (LAVSAN).

Image 1. Chapulhuacanito: place of grasshoppers and masks.

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2022

During the days of the Xanto festival, the center of Chapulhuacanito is decorated for the attraction of the townspeople and visitors.

This year we hope that the delegation arranges it well, because the Xantolo is Chapulhuacanito's big party.

Participant of the costumed group of the San José neighborhood.

Image 2. Seed for St. John's day

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019

The cempasúchil flower that is placed on the domestic altars during Xantolo is left to dry and its seeds will be sprinkled on June 24 (St. John the Baptist's Day) of the following year. On that day they go out to their backyards and sprinkle the seeds that will give them that year's Xantolo flower.

Image 3. Tamales for the offering

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. October 2023

During the descent of masks and the days of Xantolo, the women organize themselves to make the tamales that they will offer and that will be the food for the participants of the costumed group, who will come to eat them when they finish dancing in the streets of the community.

Making tamales is one of the most important tasks and is the support of the Xantolo ritual process at the time of offering and exchanging food.

Image 4. Domestic altar

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November of 2019.

I'll be waiting for you for Xantolo so you can take a picture of me with the altar I'm going to put up here in the house," said don Barragan.

Excerpt from my field diary

In the houses a domestic altar is set up and dedicated to the deceased members of the family. Here food is placed and an offering is made, sometimes a mask is also placed, referring to their participation in a costumed group.

Image 5. Not saying thank you

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019

In the domestic offerings are placed the food that will be smoked and then eaten. In Chapulhuacanito, during the days of Xantolo, people eat what they put on the altar. When you are invited to ofrendar (consume the food on the altar), you do not have to say thank you because the food was prepared for the deceased and you are the only vehicle that consumes it in its material form.

Image 6. The descent of the devil

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2023.

In the first lowering of masks it is crucial to lower the devil masks with bent horns and standing horns. These are received by a past businessman who, upon taking them, blows copal from the sahumerio.

Image 7. The clown

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2022.

In addition to the traditional pink masks of the San José neighborhood, there are others that lead participants to create other types of characters.

This year they don't know what I'm going to dress up as, and I don't want to tell anyone because they'll copy it later.

Participant of the San José neighborhood group

Image 8. The photographer

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019.

We were at the businessman's house while everyone was preparing their costumes, when Toño arrived and told me: "You don't know what I'm going to dress up as, you're going to be surprised, Uriel".

Excerpt from my field diary

One of the qualities of the costume is that it can include elements of what they see or is happening at the time. In that case, one of the costumed decided to include my work as an anthropologist/photographer in the way I would appear during those days.

Image 9. Game of glances

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019.

After Toño's camera was destroyed, only the lens was preserved. The playful character of the Xantolo achieved a game of looks in which the look and the way of doing it were exposed.

Image 10. Music for the masks

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019.

The music of the Huapango trio is crucial in the descent of the masks of each of the costumed groups. When the trio arrives at the empresario's house, it begins to play "El canario" for the masks. In addition, he accompanies the masqueraders to their dance through the streets of the community during the four days of the festival.

Image 11. The devil in the mural

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. May 2023.

One of the most relevant masks in Chapulhuacanito is that of the devil. This is because the shape, figure and image of this mask is the way the devil appeared in this community. For this reason some murals have been dedicated to highlight the importance of this image.

Image 12. "We have to start playing cuetes". El Gordo, second businessman of the San José neighborhood.

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. March 2013.

In addition to the music, another fundamental sound aspect is the rocket or, as the people say: "echar cohete". Its thunder in the sky creates a festive atmosphere that serves to warn a large part of the community where they are preparing for the offerings, the lowering of masks or that the costumed are getting ready to go out into the streets of the community.

Image 13. "Touching the floor means that the past is already here among the living". Cecilio, a former businessman from the San José neighborhood.

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. October 2023.

During the first mask lowering, only seven main masks are lowered. In this case, the crouching horned devil, the standing horned devil, the older cole, the grandfather, the grandmother, the mask of the second businessman and the mask of the chiflador were lowered. After lowering them from the false ceiling of the house where they are kept, it is necessary that the masks touch the ground, which is a sign that the deceased are already on the earthly plane, where we, the living, live.

Image 14. "In the first descent it is something intimate with few people, and in the second descent it is big". El Gordo, second businessman of the San José neighborhood.

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. October 2023.

For the second descent of masks, the group of costumed people from the San José neighborhood organizes and sets up chairs to wait for about 50 people, sometimes there are more. All the people are offered tamales, coffee, chocolate and soft drinks.

Image 15. Transmissions

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2023.

The second descent of masks can be such a big event, that businessmen manage the transmission of the ritual. Sometimes it is only given through social networks and other times they take the community radio so that it can broadcast.

Image 16. Mask heights

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. October 2023.

The altars where the masks are placed are usually larger than the domestic altars. This leads to a greater elaboration of the arch and cempasúchil flower necklaces. Making a bow for the lowering of masks carries a signifier of prestige and pride.

Image 17. Have your costume ready to go out.

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019.

The participants of the costumed group meet at the businessman's house where they take their mask and prepare their costume. In some occasions they take clothes that are already in the place of the masks and that are used year after year, in others they wear their own clothes. In addition to disguising themselves with masks, some men also dress up as women to make couples when dancing.

Image 18. The new generations

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019.

If you notice, this group brings a lot of children, many of them are attracted by it and come here, and that's good because they are the new generations. I used to walk like them since I was little, behind the costumes.

El Gordo

Image 19. Small mask

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019.

I have already made my son a small mask, which fits him well and can be used for the Xantolo.

Chilo, community masquerader

Image 20. Sweat

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. October 2019.

Imagine all that a mask has gone through inside, it has the sweat and energy of many people who have worn it.

Óscar, disguised as the neighborhood of San José

Image 21. The descent from the school

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. October 2023.

Each of the masks that is lowered has to be smoked before being placed on the floor and given aguardiente to drink.

Image 22. Passing the drink

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. October 2023.

Deliver and receive: these are words used in the lowering of masks and consist of a dialogue between present and past businessmen, in which sharing a drink (aguardiente) is fundamental during the ritual, to strengthen the process in which they welcome the deceased.

Image 23. Sahumar not to go crazy

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. September 2018.

During the lowering of masks, it is necessary that all the people attending the ritual pass by to smoke them. This will prevent them from going crazy, which consists in not falling asleep and listening to the disguised people. In case of going crazy, the entrepreneur has to carve a mask and give to drink the powder that comes out with aguardiente.

Image 24. Óscar's unveiling

Chapulhuacanito, Tamazunchale, S.L.P. Mexico. November 2019.

In the unveiling, when one takes off the mask, I feel sad that I will not return until next year.

Oscar

Of Zamorano insomnia. What is not talked about, but what the night allows to be shown

Laura Roush

El Colegio de Michoacán

likes to walk at night and during the pandemic began documenting aspects of the night in Zamora, Michoacán, where she lives. She holds a PhD in anthropology from the New School for Social Research and teaches at El Colegio de Michoacán.

Image 1. Zamorano's insomnia. What is not talked about, but what the night allows to show.

Entrance hall in Jardines de Catedral, Zamora, Michoacan. Mural by Marcos Quintana, 2019

Image 2. Pandemic novena

Colonia El Duero, Zamora, December 2000

Image 3. "When the Merza closes at eleven o'clock, I want you back here".

Parish of St. Peter and St. Paul, Infonavit Arboledas. 22 hours and 55 minutes. January 2020.

Image 4. Chiras pelas. At night the streets and sidewalks cool down and you can play more fun. Some neighborhoods in the city offer the conditions for children to enjoy nightlife all year round.

Cathedral Gardens, Zamora, 2018.

Image 5. On Christmas and a few other holidays, the schedule rules are suspended.

Cathedral Gardens, December 24, 2020, almost midnight.

Picture 6

Cathedral Gardens, Zamora, New Year, 2021.

When the Douro River was diverted, segments of its former course became curved streets, sometimes narrow and with few connections to other streets.

La Lima, July 2023.

The narrow and curved streets of the old course of the Duero allow the continuation of the custom of street altars because they protect them from traffic. However, they say, because of the violence and disrespect, many now prefer to set them up inside the houses and publicly visible altars are scarce.

Day of the Dead, 2020, La Lima.

Image 9. Traffic goes down, kids go in and cats come out.

Colonia El Duero, September 2023.

Image 10. Already locked up

Jacinto López, January 2021.

Image 11. Day of the Dead Altar

Infonavit Arboledas, 2021

Image 12. A multi-family altar housing memories of an entire street

Arboledas Third Section, Day of the Dead, 2021

Image 13. "What hurts is the fucking killing".

Day of the Dead, 2021, La Lima

Image 14. Two fallen from the same family. Suddenly, the third one was killed

The Douro, July 2021

Image 15. "It's just that he was in it".

The Douro, July 2021

Image 16. "No one understands. But if you isolate yourself, you can go crazy."

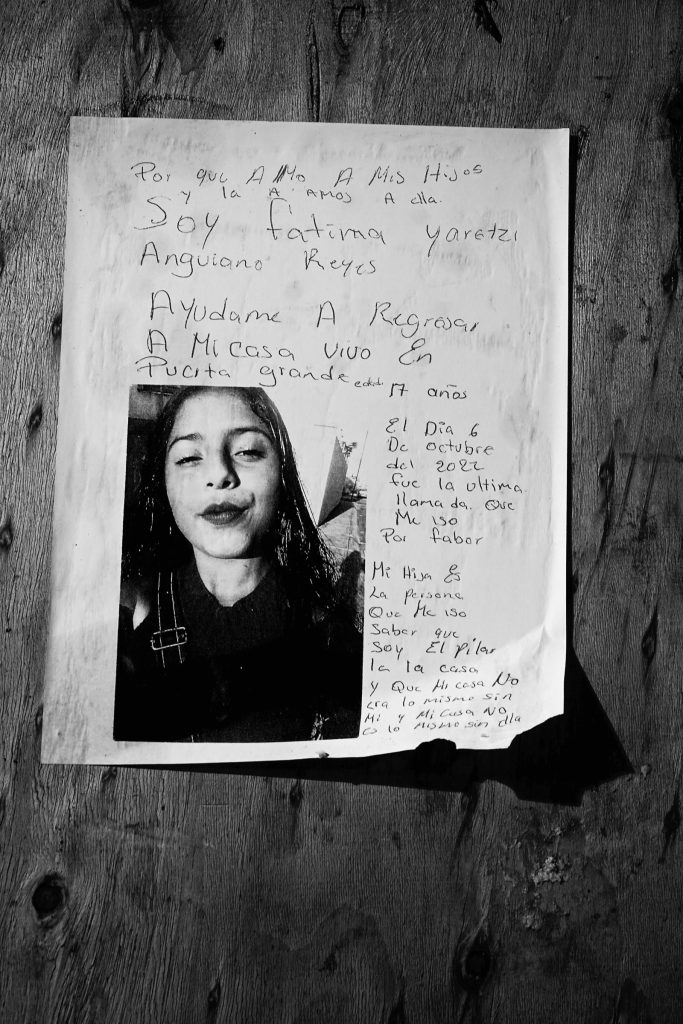

Zamora, October 2022 (photo); conversation about the purpose of these photos, October 2023.

She wanted to remain anonymous, but she also wanted her children to be seen, for one might be alive somewhere.

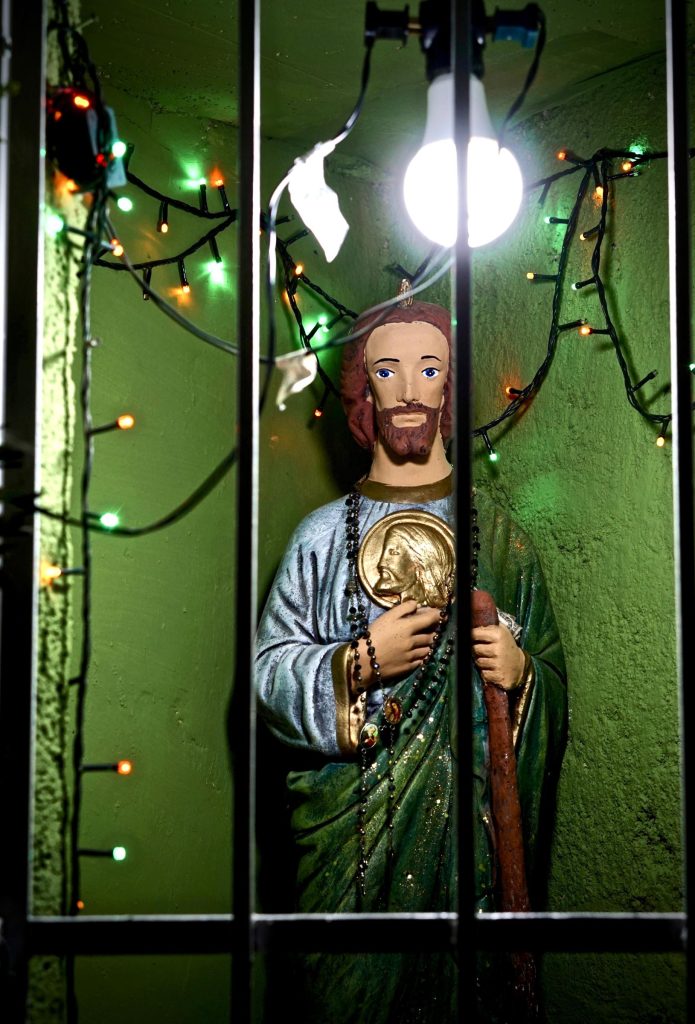

Image 17. Altar to Saint Jude Thaddeus

Same place as in the previous image, Zamora, October 2022.

The situation of women who had to take on these tasks due to the kidnapping-disappearance, imprisonment or clandestinity of their partners is intrinsically different....

The situation of terror in which they lived required various forms of concealment, even of personal pain. It included trying to get the children to go about their daily activities as if nothing had happened in order to avoid suspicion. Fear and silence were constantly present, with a very high emotional cost.

Elizabeth Jelin, anthropologist, on the Dirty War in Argentina (2001:105)

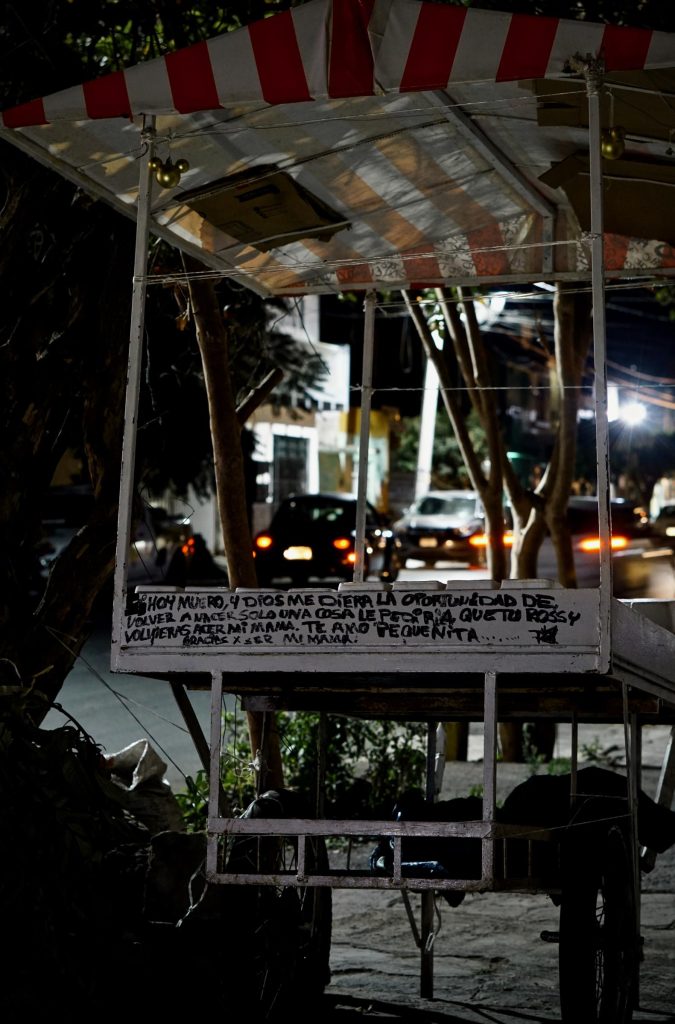

If I die today, and God gives me the opportunity to be born again, I would ask only one thing, that you, Rossy, be my mother again. I love you, little one. Thank you for being my mommy."

Avenida Virrey de Mendoza, January 2021.

Picture 19

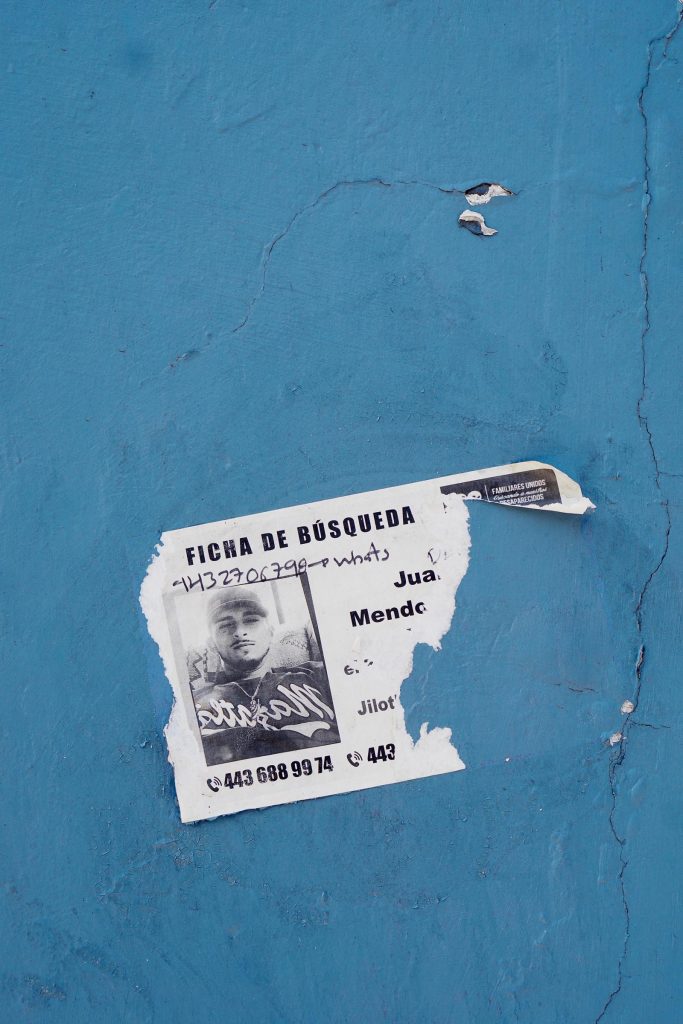

Arboledas Second Section, October 2023

There is a great stigma attached to missing persons. In Zamora, the population has internalized the phrase "he was up to something" to justify any crime against humanity. I believe that this is a reflection of the fact that we have lost the ability to empathize with the pain of others, we think that violence is a reasonable means to punish or resolve conflicts, and it also gives us a false sense of security, since it will not happen to me, only to the other, to the one who is "up to something".

This symbolic violence exercised by the population has had various repercussions on the victims of forced disappearance and murder, and their relatives, in the search for truth and justice. It would seem that, if the victim had any link with illicit activities, to search for them, to demand justice or their appearance alive, would be illegitimate in the eyes of society, but also of their relatives, who out of shame or "lacking moral authority", are forced to live in fear and silence.

Itzayana Tarelo, anthropologist, personal communication, Zamora, October 2023.

Picture 20

Guadalupano Shrine, Zamora Centro, July 2023

What level of violent deaths is socially acceptable? If we aspire to a death rate of 9.7 intentional homicides per one hundred thousand inhabitants, registered at the beginning of Felipe Calderón's government, or 17.9 when his administration ended, the 39 murders in Zamora and 15 in Jacona, in April alone, are a lot.

But if we compare with the 196.63 (per hundred thousand) publicized by the national press, according to the report of the Citizens' Council for Public Safety and Criminal Justice (March 11, 2022), then "we are doing well", since 39 murders per month would result in 468 per year, slightly above the 401 that result from an annual rate of 196.63%. Ah, but if we compare with the 57 intentional homicides in Zamora and the 21 in Jacona noted in December 2021, April is going down!"

José Luis Seefoo (2022)

Image 21. Asphalt up to the very trunk

Avenida del Arbol, May 2023.

A saleswoman from hot dogs she told me how two murderers waited for their victims among the trees. Although the ones she mentioned were just rickety ficus trees; to her, they added to the darkness of the scene. She went on to relate other murders in the area, including one on the next street. Drug addicts hung out there, she said, until several large trees were cut down. When I insisted, he acknowledged that the military rounds began around that time. However, she stuck to the fact that the trees were the main factor. For this lady, the trees were metonymically linked to danger and crime.

For an ex-taxi driver, these were thugs themselves. He told me of a dead tree that fell on top of a car, killing the parents and orphaning the children riding in the back seat. "No tree bigger than a person should be allowed!" he insisted. We also talked about the homicides that day, but he saved his indignation for the trees. When those responsible cannot be named for fear of reprisal, even trees can be a focus for articulating anxiety.

Rihan Yeh (2022) The Border as War in Three Ecological Images

(The border as war in three ecological images)

Image 22.

Avenida del Arbol, June 2023.

Picture 23

Day of the Dead, 2020, Colonia El Duero

The homicides, stated as 'confrontations', are in reality forms of manhunts of marginalized youths. Both victims and direct killers do not occupy high positions on the social ladder.

Thus, as long as the pain of loss and the smell of incense invade the homes of popular neighborhoods, intentional homicides will not drop sufficiently. If wakes and funerals were to take place in "residential" spaces, we should expect important changes...

Anonymous (textual)

Picture 24

Colonia El Duero, January 2022

Image 25. The food stalls with their lights summon from afar to live with neighbors or strangers, a nocturnal sociability that does not give up.

El Duero, January 2022

Image 26. Just called "The Metataxis": it gathers information from all cab drivers.

The Douro, February 2021

His hamburger stand is the one that closes most nights. He has the gift of getting watchmen, watchmen, policemen, hospital staff, taqueros who have already set up their stalls and who have also heard something, and a whole range of people who can't sleep for some reason.

Cab driver committed to the night shift and occasional diner at the hamburger stand.

Colonia El Duero, October 2022

After midnight, the conversation often becomes more philosophical. Bits of news that will never make it into a newspaper are gathered.

Image 28. Another member of the night owls' gathering. Topic: What is the fault of the night if you are killed during the day?

Colonia El Duero, 2022

Image 29

Zamora Centro, March 2023.

On March 5 we went out to march in Zamora for 8M. I was accompanying the contingent of women searchers and we were gluing, with paste, the cards of the missing persons. A few days later I passed by those streets again and I saw that they had tried to tear them up.

A friend of mine told me that in Queretaro the public cleaning people were instructed to remove all kinds of propaganda or posters and that is why they tore off the missing persons' cards. I suppose they do the same thing here, although sometimes the advertisement of an event lasts longer on a wall than the face of a missing person.

Anonymous, Zamora, October 2023

Image 30

Zamora Centro, August 2023.

To the perpetrators of the violence, the searching mothers have said "We don't want the guilty ones, we only want our children". With the celebration of masses and vigils in which prayers are said and candles are lit with the photo of their family member, the mothers seek God to soften the hearts of those who took their sons and daughters, not to abandon them in their search and to protect their family member wherever he or she may be.

Anonymous, Zamora (textual), October 2023

Image 31

Zamora, April 2023

We accompany ourselves with Our Lady's sorrow today, in the hope that she will be moved with us.

Anonymous, ending the Women's March of Silence

The March of Silence in the Catholic world is typically a procession of men commemorating the death of Christ on Good Friday. The Women's March of Silence has grown in parts of Latin America in recent years. In some, as in Zamora, it provides a language for some of the mothers of missing or dead young people.

Image 32. Panther

Colonia El Duero, October 2020

These pains have no words. One keeps silent more out of modesty than fear. Crying screams and one hides the tears. All loss does not want to show itself impudently.

One closes oneself and keeps silent while one's heart burns, either for love or for absence. Impotence hurts and one knows that there is no return or solution. Poetics can only murmur. The anthropologist sometimes errs on the side of exhibitionism and fills with theoretical frameworks what hurts to mention.

The Douro Panther (textual), October 2023

Image 33. Anonymous. She made this figure representing her husband after he was killed.

Zamora, November 2023

Image 34

Bank of the Douro river course

Four months ago (May 30, 2023) a teenager was killed in my neighborhood when he was going to pick up his girlfriend at CBTIS. Rumors said it was for stealing his cell phone. Some guys on a motorcycle chased him and shot him many times, until he fell dead on the corner of a vacant lot, where people throw garbage.

A few days after he was murdered, his family put up a small metal cross, some plastic flowers and a candle, but someone came by and tore the cross down and people threw garbage there again.

My mother told me that she felt bad that the boy didn't have a cross, so she made him another one with some pieces of wood she found in the yard. She put it up and, days later, she found it lying in the vacant lot, as if someone had thrown it. We think that this could only have been done by the person or persons who killed him, that the cause of his death was personal and not a robbery, as it was said.

We feel that it was a matter of hatred, of a lot of anger against the boy, because they did not respect the place where he died, nor the crosses. I feel that there was a desire to erase him, to erase his memory.

Anonymous (verbatim), October 2023

Image 35

March 29, 2024

The Women's March of Silence grew exponentially; the municipal government estimated that 15,000 people participated.

Silence was strictly maintained, punctuated only by drums with a slow, synchronized rhythm between contingents. Likewise, other signs were discarded and only those that reminded to remain silent were kept.

Image 36

Guadalupana Shrine of Zamora, March 29, 2024

They were received by their rector, Father Raúl Ventura, who congratulated them because "Zamora is consolidating its position as a leader in religious tourism.

Image 37

Avenida Virrey de Mendoza, January 2022

Where language must be imprecise, a flame in the night communicates, even if it is difficult to know who put it there or to whom it is addressed. To the dead man himself, of course; to God.

Image 38. During the day they are not even seen. At night they acquire convening power

Hidalgo Market, September 2022.

Image 39. It hurts. See it

Jacinto López, October 2022.

The author would like to publicly acknowledge the support and patience of her colleagues at the Centro de Estudios Antropológicos, Colmich; the collaborations of Itzayana Tarelo and Reynaldo Rico Ávila to think the narrative arc from a hundred photos or more; the enthusiasm of Renée de la Torre, Paul Liffman, Melissa Biggs and Gabriela Zamorano, as well as the complicity of Ramona Llamas Ayala.

Dedicated to the memory of Julio César Segura Gasca, alias the FUA (1967-2024), poet of the Zamorano night.

Bibliography

Citizen's Council for Public Safety and Criminal Justice (2022). "Ranking 2021 of the 50 most violent cities in the world." https://geoenlace.net/seguridadjusticiaypaz/webpage/archivos Accessed: August 2023.

Jelin, Elizabeth (2001). The work of memoryMadrid: Siglo xxi.

Seefoo Luján, José Luis (2022). "Zamora va... muy bien?", Semanario. Guide. https://semanarioguia.com/2022/04/jose-luis-seefoo-lujan-zamora-va-muy-bien/

Yeh, Rihan (2022) "The Border as War in Three Ecological Images," in Editors' Forum: Ecologies of War, thematic issue, in. Cultural Anthropology. January. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/series/ecologies-of-war

The awareness of being looked at: giving a view of the tianguis stall

Frances Paola Garnica Quiñones

El Colegio de San Luis, San Luis Potosí, Mexico.

is a Conacyt postdoctoral fellow at El Colegio de San Luis. She holds a master's degree and PhD in Social Anthropology with Visual Media from the University of Manchester, UK. Her research topics include the perception and imaginary of spaces, Chinese migration in San Luis Potosi and ritual and therapeutic uses of peyote from a biocultural territory defense approach. She is co-director of the documentary ...And I'm not leaving the neighborhood! (2019).

Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6957-1299

Image 1

Tianguis: a place to watch

CDMX, 2012.

Once a week the Ruta 8 de Mercados sobre Ruedas is installed in eight different neighborhoods of the CDMX. People visit with certain expectations of the place:

The tianguis is a light bulb on, a journey, a back and forth, going in search of something with the desire to get something, open space, without walls, without walls. There is room for everyone; it is a tradition, an adventure, a means of sustenance, a job and a chinga. - Rodrigo, dealer.

Picture 2

"The tianguis can be seen, smelled and touched" (Jorge, art dealer).

CDMX, 2013.

The atmosphere of a tianguis is generated in large part thanks to the work that tianguistas put into the presentation of their stalls.

The main expectations of a tianguis from the perspective of the marchantes are that, 1) its installation is on the public street, 2) there is an atmosphere of exploration, sociability and personalized attention, 3) there are products that are not found in other establishments and at low cost, 4) the visit is recreational and enjoyable, 5) there is room for maneuver in the commercial exchange, such as bargaining and bargaining.

Picture 3

"Why do I always get hungry at the tianguis?" (Carlos, dealer)

CDMX, 2013.

These expectations are not the result of a marketing study where the preferences of the potential clientele were calculated and then the tianguistas created and executed an action plan accordingly. They are the result of the observations and adaptations made by the tianguistas in order to set up a street sale. They bring together a series of knowledge about the use of space, hygiene, product presentation, interaction with vendors and internal social organization. Since stalls are usually passed down from father to son or daughter, this knowledge is acquired and inherited over decades of coexistence with vendors.

Picture 4

Assemble the stand

CDMX, 2013.

At eight o'clock in the morning, the constant whistle of the devils or chargers alerts pedestrians walking in the middle of the traffic of devils (wheelbarrows). Heavy wooden boards on the floor mark the place of each stall. Half-assembled stalls, like skeletons, wait to be dressed. But the tianguistas must take into account the rules imposed by the association itself, the government and the neighbors of each neighborhood: install the awning of the indicated color, have the stall tubes painted in the same color, do not exceed the allotted meters, do not ruin flower boxes or fences of the neighborhood, keep the boxes and other materials tidy in the back of the stall and avoid cables, ropes and obstacles in the aisles, among others.

Picture 5

Diablero

CDMX, 2013.

The diableros perform work that requires great physical effort. A diablero can carry up to 100 kilos. They load, unload, assemble and disassemble the tubes of the stand. They can also act as assistants, serving customers and giving "testers" to the vendors. For many migrants, this job is their first entry into the world of work in the CDMX, as the requirements are minimal.

Picture 6

Assistant

CDMX, 2013.

The stall owners usually hire employees to help them unload the merchandise and set up every day. The tianguistas who do not have their own cargo truck hire freight drivers who store the merchandise in their truck overnight and deliver it early in the morning to the neighborhood where the tianguis is to be set up.

Picture 7

The tailor of the post

CDMX, 2012.

Abel, an assistant at the banana stand, resembles a tailor who puts the finishing touches on the stand. A native of Veracruz, he considers his trade to be that of a farmer, but he has developed diverse skills over ten years of handling the stall's structural materials. Abel prepares and adapts the stall for possible weather conditions: clear, rainy or windy. He uses coins that he wraps and ties around the corners of the stall's canopy to get a better grip. He says he likes this work because it awakens his creativity.

Picture 8

The art of banana placement

CDMX, 2012.

Abel takes the bunches of bananas from the rows he already formed and, with a curved knife, skillfully cuts the top of the stem without splitting the bananas, making the joint look flatter:

I'm giving them a view. It's more attractive; the bananas look fresher and more appetizing..

Giving a view consists of working on the aesthetic and spatial presentation of the stand and the products that compose it.

Picture 9

The stocking stall

CDMX, 2012.

A few meters from the banana stand, Olimpia is unpacking the merchandise from her hosiery stand. Her mother inherited it from her. After a hired loader assembles her two-meter stand and places large drums full of clothes, Olimpia arranges the merchandise. As part of give view to her stall, she also often dresses her merchandise, a strategy that has helped her sell.

Picture 10

Giving sight is inherited

CDMX, 2012.

On the front counter, Olimpia places colorful socks that she has had dyed, because it's cheaper. She stretches them along the corner of the stall, creating a rainbow of nylon. Light filters through the transparent material, highlighting the delicate patterns of the stockings, which are hung like invisible legs. Bundles of stockings portraying several white-skinned blonde women hang at the front of the stall, swaying delicately in the morning breeze.

From my mother I learned to show my stockings like this. She always told me to hang up my stockings just like this. They look great, don't they? Don't they? Look at them. - Olimpia, tianguista.

Picture 11

Variety in 2 meters

CDMX, 2012.

The extensive variety of merchandise that Olimpia handles includes more than a hundred different products. After three hours of arranging socks, tights, leggings, tights, stockings, lycra skirts and so on, Olimpia arranges her seat, which consists of a stack of box tops on a storage box, and checks on Galleta, her little French Poodle who is napping very comfortably on a cushion.

Picture 12

Giving a view is innovation

CDMX, 2013.

During the 1980s, before the Free Trade Agreement, the tianguis were the place where innovations were found. Things that were not allowed to be sold were sold freely in the tianguis. It was a place of novelties. People liked to find something new, even if it was the same thing, but in a different form, for example, curiosities, like jicama. Instead of selling it in a jar, you put a stick to the slice of jicama and it becomes a special popsicle called "jicaleta". That's something innovative and it was sold at the tianguis. Fruit covered with chocolate, things like that. The idea was to look for something attractive, something curious. It was more than just satisfying a desire to consume. - Roberto, tianguista.

Picture 13

Recognition comes through the eyes

CDMX, 2012.

On Sunday more foreigners arrive and I would imagine that in their countries there are not as many things as here. It is a marvel for them to see our work, because it is not easy to arrive and find everything already shaped, washed, cut, sliced; it is a great task that we do from very early in the morning and they are amazed. And they see it as a treasure that we have. I don't know, maybe, if we had it every day, it became more habitual and maybe you don't value it so much. You see the enthusiasm, the expression on their faces, how they stand with their cameras, film and ask for permission. Many are more observant. They try to see the structures we have to work with, because it is not easy, and they are even more amazed when they go the next day and there is nothing of what they saw the day before.. - Abel, tianguista.

Picture 14

The good trader

CDMX, 2012.

The tianguis reminds you not to assume that there are no faces on the fruit. Here at the tianguis, you can see that the vendors work for the goods. They share their knowledge about the produce, how it can be eaten. It's a more direct approach, not like in the storefronts. - Octavio, art dealer.

Picture 15

Oranges with a view

CDMX, 2013.

Twice a week Roberto, tianguista and representative of Route 8, buys 90 kgs. of oranges in arpilla, as many kilos of Valencia oranges, grapefruit and pineapples.

In Abastos, a higher monetary value is given to oranges that "have eyesight", that is, those that are large in size -and therefore heavier-, uniform in color and without blemishes.

Picture 16

Automatic and manual aesthetic selection

CDMX, 2013.

At the Central de Abastos, a machine sorts the oranges by size and, via a conveyor belt, sorts them into compartments. Once the oranges have fallen into these compartments, two fruit sorters pick them up and manually select the oranges that have spots or dents.

Some fruits get leaves stuck to them when they are growing and get stained. We take care of this. We select the best ones, and the ugly ones we remove so that the fruit has a better presentation. This is what helps people consume more.- Ángel, worker at the Central de Abastos.

Picture 17

Back at the post

CDMX, 2013.

Roberto finally arranges the oranges in his stand. These oranges have gone through a selection process that is part of a chain involving the aesthetics of the product. The oranges with the "best look" are given at a more expensive price to the dealer. Roberto also sources oranges for juice, pineapples and grapefruit.

Picture 18

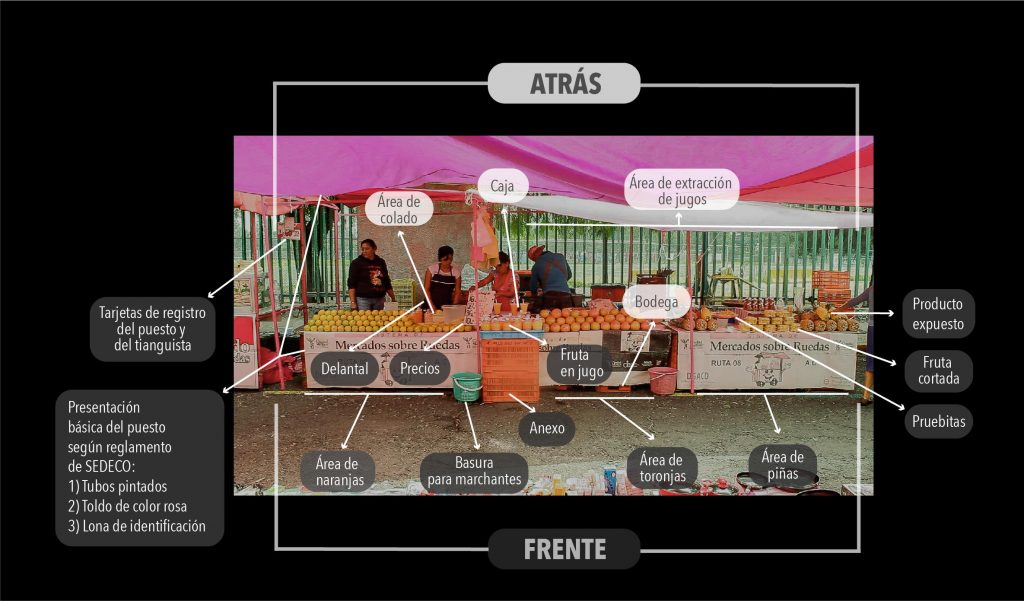

Map of a tianguis stand set up in the vicinity of the Velódromo sports center.

CDMX, 2013.

These are the basic elements that make up the assembly and presentation of a Ruta 8 citrus stand. Variations tend to occur with respect to the type of products being sold, the neighborhood where the stand is set up, where space may be larger on some streets than on others, and the needs of the vendors. Annexes are more tolerated in Velódromo, where there is much more space than, for example, in La Condesa.

Picture 19

Social control and view

CDMX, 2013.

Roberto, as a representative of Ruta 8, along with the coordinator of the Markets on Wheels Program and a representative of a neighborhood committee, review the news to measure risks, threats and points for improvement. They set out to carry out the monthly supervision of Ruta 8's facilities in the Condesa neighborhood. The criteria for this supervision focus on the presentation of the stall and the use of the space.

Picture 20

Aisle width

CDMX, 2013.