Green handkerchiefs for legal abortion: history, meanings and circulations in Argentina and Mexico

- Karina Felitti

- Maria del Rosario Ramirez Morales

- ― see biodata

Green handkerchiefs for legal abortion: history, meanings and circulations in Argentina and Mexico

Received: August 21, 2019

Acceptance: December 2, 2019

Abstract

The green scarf is distinctive of the National Campaign for the Right to Free and Safe Legal Abortion of Argentina. Historical heir to the white scarf of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, in 2018 it was adopted as an emblem that articulates the claims for reproductive rights in Latin America. This article investigates its history and the relationship it weaves with the human rights movement and the transnationalization of feminisms, with a focus on its circulation in Argentina and Mexico. We suggest that the green scarf, as a traveling symbol and cognitive bridge, ties together different identities and modes of political intervention of contemporary feminisms, identifies and mobilizes, and at the same time leaves particularities and differences in latency, opens up to new alliances, generates debates and produces responses.

Keywords: legal abortion, human rights, reproductive rights, green scarf, traveler symbols

Green Scarves For Legal Abortion: History, Meanings And Circulation In Argentina And Mexico

Green scarves have been the symbol for Argentina's national campaign for the right to free, legal and safe abortion. A historic heir to the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo's white handkerchiefs, it emerged in 2018 as an emblem to articulate demands in favor of reproductive rights in Latin America. The article explores the scarves' history and the relationship they weave with human rights movements and the trans-nationalization of feminisms, with a focus on their circulation in Argentina and Mexico. We suggest the green bandanna, both as a traveling symbol and a cognitive bridge, unites contemporary feminisms' different identities and modes of political interventions at the same time it abandons particularities and latent differences; opens up new alliances, gives rise to debate and produces protest.

Keywords: legal abortion, green scarves, reproductive rights, human rights, traveling symbols.

Introduction

LThe green handkerchiefs displayed in the air in a joint action - “Pañuelazo” - are part of the visual heritage that documents the latest feminist mobilizations in Latin America. This symbol, heir to the white scarf that distinguishes the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, those women who in April 1977 organized to demand information about the whereabouts of their detained sons and daughters disappeared due to State terrorism in Argentina, was proposed by the National Campaign for the Right to Safe and Free Legal Abortion - hereinafter "the Campaign" - which was launched on May 28, 2005. Since then it has been recognized by activists as a symbol of the struggle for the legalization of abortion and exhibited during the National Meetings of Women of Argentina - since 2019, named Plurinational Meeting of Women, Trans, Transvestites, Lesbians, Bisexuals and Non-Binary - and mobilizations such as those of March 8 (International Working Women's Day), Ni Una Less - every June 3 since 2015 - and May 28 (International Day of Action for Women's Health).

The debate in the Argentine National Congress of the project for the legal interruption of pregnancy presented by the Campaign offered an opportunity for visibility and circulation that exceeded the most optimistic expectations.2 Everyday life was dyed green, as documented in their photographic essay by Valeria Dranoksky and Lucía Prieto. "The handkerchiefs are not saved" was launched as a slogan at the end of the legislative debate, and they have not been saved. From a universe of shared situations and demands - sexist violence and femicides without a state response, deaths due to clandestine abortion, forced pregnancies due to illegal abortion, denial of reproductive autonomy, violation of human rights - beliefs and values that promote equality and gender equality, the responsibility of patriarchy for the violation of rights, confidence in the power of collective struggle and the ability of feminism to articulate actions and transform reality, the handkerchief managed to be an object that globally identifies the movement for legal abortion and also congregation and collective action beyond that specific lawsuit. Each handkerchief, with its so-called "Raise your handkerchief wherever you are", managed to overcome national and physical borders. The handkerchief was made emoji, decorative motif in pastels and cupcakes, pins, t-shirts, notebooks and stickers, profile photo frame Facebook, and wrapped statues such as the Monument to the Flag in Rosario, Argentina, Diana the Huntress and the monuments to the mother and Francisco I. Madero in Mexico City, and covered the mouth of the Virgin in the work Feminist Maria by the Argentine artist Coopla.

The scarf changed color in some countries and adapted its slogans to local peculiarities with the same conviction, which is sung loudly and danced in the streets: “Aleeerta! Aleeerta! Alert that the feminist struggle is walking in Latin America. Tremble! Let the machistas tremble! Latin America will be all feminist ”. This traveling symbol articulated the fight for sexual and reproductive rights - in particular the legalization of abortion - visually, performatively and emotionally - and offered the same symbol to women, men and trans people, to activists and militants, to legislative representatives and political leaders. that promote the legalization of abortion. In this last group were also located those who support neoliberal policies denounced by social movements and popular feminisms, showing that the green scarf could be used, promoting legalization, militarization and also voting pension cuts. Thus, the green handkerchief coexisted with the difference between those who use it and with other handkerchiefs of different colors and slogans that arose in its heat - due to a new adoption law, outside of Macri, Not One Less, against animal abuse - especially the orange scarf that demands the secularism of the State; and it also generated its antagonistic response: a light blue handkerchief that brings together the position against legal abortion with its phrase "Let's save both lives."

In this article we propose a dialogue between the political and affective meanings of green scarves in Argentina and Mexico, two countries with antecedents of political and feminist ties in recent history. Mexico was one of the main destinations for Argentine political exiles during the 1970s, several of whom met and adhered to feminism in that country. Since then, publications, teachers, students, activists, slogans, strategies have not stopped circulating through academic spaces, and also outside them, until they reach this traveling symbol and object of affection that is the green scarf. We are interested in delving into the cognitive bridges (Frigerio, 1999) traced by white and green scarves in recent Argentine history, and how the green scarf travels, inhabits and acts on the Mexican scene. Based on specific academic studies, journalistic notes, interviews, photographs and statements published in the media and social networks, as well as our own observations from participants in various mobilizations that we refer to in this text, we ask ourselves about the modes of identification that provides the green scarf, considered today as an emblem of feminist struggles in Latin America; the negotiations and adaptations that accompany its adoption, its political power and its emotional anchoring. Along these lines, we present our findings from fieldwork and we also relate our own experiences; We thus make visible the ascription to a political cause from carrying a symbol and the challenge of studying its meanings as academics, women and feminists.

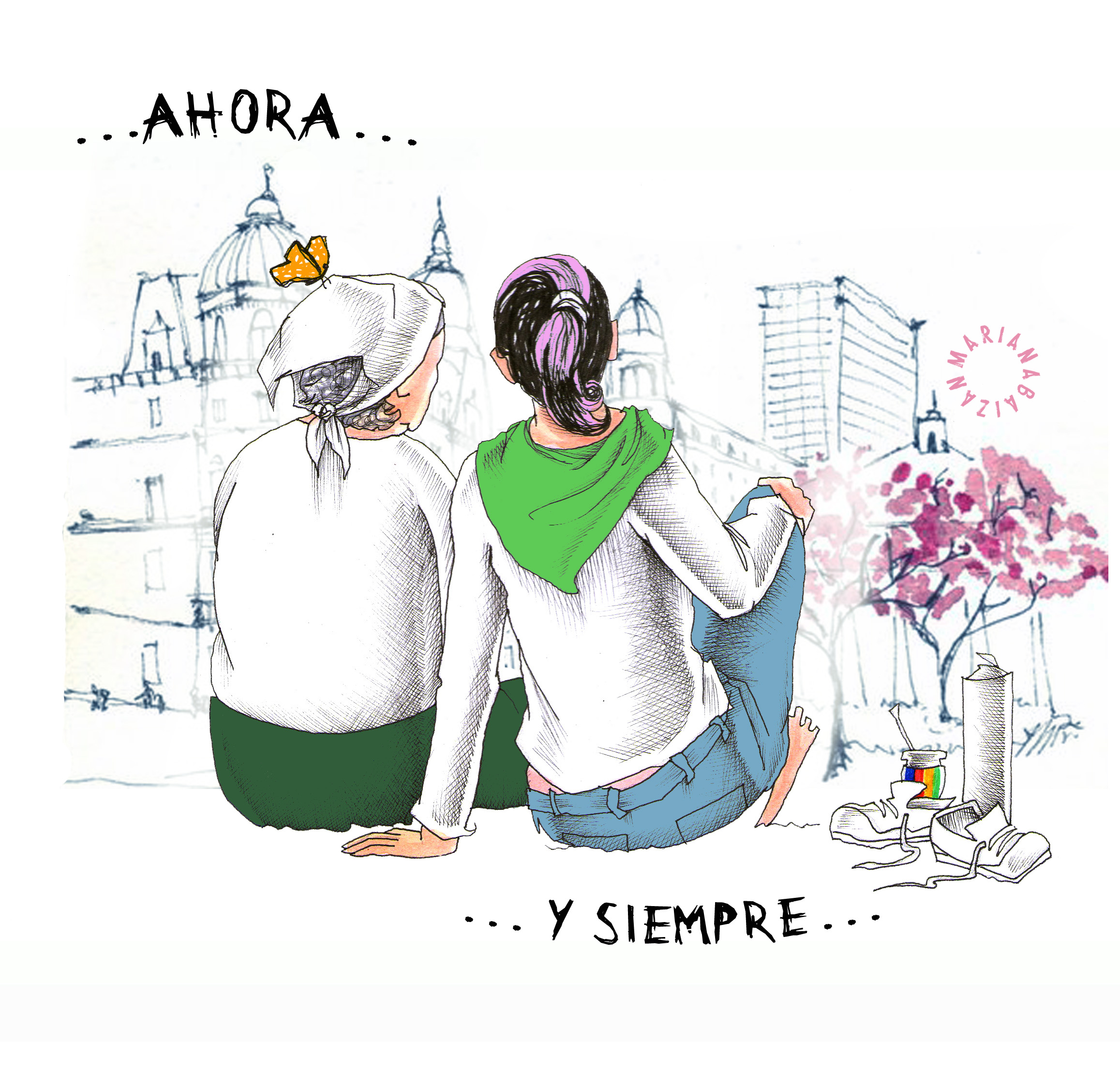

With these objectives, in the first place we document some background on the discussion of the law of Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy (ive) in Argentina and the legal situation of abortion in Mexico. Then we present a tour of readings and images that suggest the connection of feminist struggles with the struggles of the human rights movement and recent Argentine history, and the handkerchief as a symbolic element of bonding. In a third moment, we analyze the circulation of the green scarf in Latin America and its adoption in Mexico, with references to the model of dis, trans and relocation used to explain the crosses, dialogues and paths of objects and religiosities (De la Torre, 2018 ), making dialogue the interpretative frameworks of the studies of social movements and religious movements. We propose the hypothesis that the green scarf is part of a civic ritual that unites senses and struggles, without neglecting the identity and local particularities, nor the tension between the individual and the collective in the contemporary feminist context that, as Álvarez (2019) points out ), goes beyond the organizations and spaces with which it has traditionally been associated. The set of photographs that we include were taken during the mobilizations and women's meetings held in 2018 and 2019, and the illustration "The two handkerchiefs" that went viral in that period. Its insertion in the text does not have a mere illustrative purpose, but rather proposes to go further, “building a single argument, where both the text and the image merge to give strength to the explanation” (Suárez, 2008: 23).

The struggles for legal abortion in Argentina and Mexico

The Argentine Penal Code of 1921 classifies abortion as a crime against life and the person, at the same time that it provides for two cases in which it is not punishable: “1º) If it has been done in order to avoid a danger to life o the health of the mother and if this danger cannot be avoided by other means; 2nd) If the pregnancy comes from rape or an attack on indecency committed on an idiot or insane woman ”(article 86, paragraphs 1 and 2). The scope of this regulation was many times debated and adequate in response to individual judicial presentations. In 2007, the Minister of Health Ginés Gonzalez García approved the distribution of the Technical Guide for the Care of Non-Punishable Abortions, which made available to physicians the clinical and surgical procedures recommended by the who for the termination of a pregnancy, including medical abortion. In 2012 the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, in the ruling known as fal, established that every woman who became pregnant as a result of rape should have access to a non-punishable abortion without the need for judicial intervention and thus supported the three causes already included in the Penal Code - life cause, health cause and rape (Ramón Michel and Ariza, 2018) - but it was not able to ensure access to this practice in all the country's institutions. In 2015, the Ministry of Health of the Nation framed the new version of the protocol in the rights to personal autonomy, privacy, health, life, education and information, without reducing the different obstacles faced by applicants and providers of the service (Burton, 2017). Meanwhile, feminist organizations and networks - such as Socorristas en Red - that were already accompanying the decision to interrupt a pregnancy and reported on the use of misoprostol in these procedures, gained visibility, recognition and support by offering a concrete response to those who required an abortion ( Morcillo and Felitti 2017).3 The change of government at the end of 2019 restored to the rank of Ministry what it was since September 2018, under the management of the Alianza Cambiemos (2015-2019), the Ministry of Health, with the return of Gonzáles García as minister and a last updating the protocol from a public health approach, with numerous scientific sources and legal guarantees.4 This was presented to the press at a meeting with several members of the Campaign and new officials who displayed their green handkerchiefs there, in a gesture that augurs important changes and is already generating resistance.

These handkerchiefs were part of the public stage when, on the morning of June 14, 2018, the project presented by the Campaign achieved a narrow victory in the Chamber of Deputies (129 in favor, 125 against, one abstention), but on 8 August did not reach a majority in the Senate (38 against and 31 in favor, two abstentions and one absence). While the debates were taking place in each campus, thousands of women - on their own account or with their friends, relatives, colleagues and colleagues from political, party, student and union activism - took to the streets to demonstrate in favor of the project. Already in the previous weeks the green handkerchiefs with the slogan "Sex education to decide, contraceptives not to abort, legal abortion not to die" had begun to multiply their presence in the public thoroughfare and with the euphoria of the discussion in Congress, the that were distributed by members of the Campaign, free of charge or in exchange for a monetary contribution to sustain their dissemination tasks –including the production of more handkerchiefs– seemed insufficient. With different quality of fabric and printing and some shades of green, the scarves became a street merchandise offered by women and men who could be committed to the cause or simply included it as part of the souvenirs urban, in coexistence with the blue handkerchief that expresses the opposite position and was sold at the same price. A growing demand served by a heterogeneous supply was gestating the visual of the "green wave", alluding to the "waves" of feminism, until the magnitude turned it into "the green tide". The collective song that begins with the harangue "Now that we are together, now that they see us" recognized the historic opportunity to make feminist demands visible and to speak publicly about abortion - in schools, universities, workplaces, the media. and deepen a strategy started with the campaigns for the collection and dissemination of “I aborted” testimonies, and also recognizing all people with the capacity to gestate as recipients of this right, as is the case of trans men (Radi, 2018).

In public space, as the journalist Mariana Carbajal (2018, June 24) puts it, “the green scarf is a symbol and a password. It's a wink on the subway, on the train, at school. It is to show which side of history we want to be on ”. Being at night in the subway, sitting near a woman who carries the green scarf in her bag gives us security, the glimpse of a green scarf knotted in a backpack in Europe gives us pride, but it also happened to us that on the way back to our houses in the evening of this last 8M (2019), one in Buenos Aires and another in Guadalajara, we agreed to keep our badges in the bags and erase the traces of marker and green glitter because there are still spaces - many, too many - where to present ourselves in this way places us in a place of radical otherness in which we are in danger.

At the same time, in our exchanges and observations, we noticed that many women associate the green scarf with the interruption of a life and also with the rejection of motherhood, despite the fact that in street demonstrations many pregnant women wrote slogans about the desired motherhood on their bellies, and in the statements of activists in the media it was insisted that it was a matter of deciding on the reproduction and not of rejecting it. Even so, for many women who have been socialized in traditional gender roles, the green scarf is a threat to their identity and path to personal and social fulfillment. Hence, also according to our tours in classes, trainings and field work, sometimes it has been convenient not to place a barrier that would make exchanges impossible and to decide not to make our scarves visible. The complexity of the panorama was also revealed when, faced with the need for electoral alliances and votes, the green scarves were invited to coexist with the light blue ones with the aim of facing the reelection of Mauricio Macri, arguing that unity was necessary. On December 10, 2019, however, in the crowd that accompanied the inauguration of Alberto Fernández as the new president of Argentina in the city of Buenos Aires, only green handkerchiefs were seen on the wrists with raised fists that made the V of victory, emblematic gesture of Peronism.5

As we have already said, the handkerchief arose as an initiative of the Campaign that has among its founders the civil association Catholics for the Right to Decide, an organization that expresses its dissent with respect to the moral mandates of the religious hierarchy without renouncing its identity as believers (Vaggione, 2005). In a similar way to what was experienced during the debate on equal marriage in 2010 and other laws that guarantee sexual and reproductive rights (Dulbecco and Jones, 2018; Pecheny, Jones and Ariza, 2016), people identified with some evangelical churches and with the Catholic one They have unchecked moral commandments or put values related to love of neighbor, solidarity and freedom of conscience in the first place to support these regulations. Also students from confessional high schools that support the legalization of abortion wear the green scarf in their backpacks to demonstrate it, challenging the school authorities and demanding the implementation of the comprehensive sexual education law (Felitti, 2018), and a A good number of young girls participated in the 45th edition of the Pilgrimage to the Basilica of Our Lady of Luján, wearing the green and orange handkerchiefs that express the demand for state secularism, in a gesture that separates personal faith from politics. public. The mobilizations of May 8 and May 28, 2019, when the updated version of the Campaign project for an upcoming treatment was presented in Congress, again showed the two handkerchiefs together, linked, as the idea of that state secularism, defined mainly as a separation between the State and the (Catholic) Church, is essential for gender equality and sexual and reproductive rights, especially the legalization of abortion.

The blue scarf that identifies those who oppose the legalization of abortion had a specific use during the months of the debate, but it gradually disappeared from the urban scene. There are those who trace its origins to the popular demonstrations and "cacerolazos" of December 2001 but, beyond this anchoring, the celestial is associated with the sky, the Argentine flag and a certain idea of homeland based on Christian values.6 In the last 28M, on the side reserved for the "celestial", a little more than a hundred compared to thousands on the green side, separated by a cordon that the police armed, a sign could be read that said: "It was not law. No es No ”, a play on words that appropriated the hashtag feminist against harassment and sexual violence, to boast of having managed to perpetuate what for feminism is another violence.

In Mexico, the debate on the decriminalization of abortion in civil society and in the Catholic Church as an institution and in its social bases7 It has been very intense as well, and here feminism has a couple of successful antecedents. In 2006, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (pri) and the Alternative Social Democratic and Peasant Party, through the Equity and Gender Commission, presented to the Legislative Assembly of the then Federal District - today Mexico City - the proposal to decriminalize voluntary abortion. At the beginning of 2007, a great public discussion was generated and the voices of jurists, health professionals, feminist groups, conservative organizations and non-governmental organizations were included - among which the Information Group on Chosen Reproduction stands out (gire), ipas Mexico and Catholics for the Right to Decide (Maier, 2008: 32) - to support projects that included the abolition of penalties for women who consent to abortion during the first twelve weeks of gestation (gire, 2008). This proposal was approved by majority in the assembly on April 24, 2007, it was published on April 26 in the Official Gazette of the Federal District and it went into effect the next day. Subsequently, the Law of Legal Interruption of Pregnancy was the subject of a constitutional controversy that the Supreme Court of Justice heard and resolved in 2008, after an intense debate between groups for and against said law. To date, the other state that has decriminalized abortion in Mexico is Oaxaca, which happened at the end of September 2019.

Even with this background, Mexico is far from having a panorama that allows the legalization of voluntary abortions, since each federative entity has its own regulations on the subject. According to official data, all states consider rape as a legal ground for terminating pregnancy, although local criminal codes differ with respect to other accepted causes for this procedure. For example, in states such as Aguascalientes, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Campeche, Colima, Durango, Guerrero and Hidalgo, authorization from a judge or the Public Ministry is required; and in San Luis Potosí and Tabasco a “verification of the facts” of rape to access an abortion for this reason (turn, 2017). Other locally recognized causes - in Colima, Baja California Sur, Tlaxcala, Yucatán and Michoacán - are that there is a danger of death for the woman, that the pregnancy implies damage to health or genetic alterations, that the abortion is imprudential, due to non-consensual insemination , or that is practiced for economic reasons.

On the other hand, Guanajuato and Querétaro only criminally justify abortion due to rape or if the interruption was unintentional (negligent recklessness). In both states the penalties for abortion range from six months to three years in prison.8 These examples show us a complex reality where gender violence, femicides and human rights violations are linked to the demand for legal protection by the State. Abortion, even with its permitted grounds, carries a stigma and a clear mark of criminalization. Proof of this are more than two thousand criminal cases for abortion reported between 2015 and 20189, and the results of the study carried out by gire (2018) whose title is more than eloquent: “Maternity or punishment”.

In March 2019, with the antecedents of modification of local laws and an international panorama of debate, which shows progress but also setbacks, as in the United States, the state of Nuevo León - northeast of Mexico - accepted by majority the so-called Anti-abortion Law that modifies the first article of the state constitution recognizing the right to life and the protection of the state from the moment of conception until natural death.10 This situation rekindled the debate on a national scale, social and religious actors re-emerged in favor of "the two lives" and adopted the blue scarves originating in Argentina as a symbol of identification. At the same time, a faction of the Mexican green tide spoke out in favor of the legalization of abortion by wearing its green scarf on the wrists and neck, a form of use that is copied by Argentina.

As witnessed by several Argentine feminists initiators of this struggle in the second half of the century xxIt had not occurred to them before that the scarf could be used as a bracelet, it was the young girls who extended not only their urban presence but also the corporal territory to anchor it. Others put limits on the use that cisgender men make of the green scarf, if they should use it and where to place it, while some understand that, for example, putting it around the neck is a way of ostentatiously showing themselves as allies without necessarily giving up the benefits that the patriarchal system offers them in the position of "deconstructed."

Legal abortion: a debt of Argentine democracy

One of the most used arguments to legalize abortion in different contexts has been to present statistical data that show the number of deaths produced by clandestinity, and to place the issue within the framework of public health and state responsibility in it. Another way is to privilege the right of women to decide about their bodies: even if there was not a single death due to abortion, it should be legal and free. In Argentina, feminist organizations and referents, especially the Campaign, frequently postulate illegality as a "debt of democracy." According to Sutton and Borland (2017), this strategic use indicates the relevance of the claims in relation to national and international law, facilitates alliances with human rights organizations, allows the breadth as well as the specificity of the approach, connects with an extended discourse. used in Argentina and disputes the legitimacy of the counter-movement, whose strategies we will detail later. As Pecheny (2010) states, after the recovery of democracy in 1983, the divorce law of 1987 was the first successful example of the use of human rights discourse for a politics of gender and sexuality. Since then, and with different intensities according to the governments in turn, progress was made in legal regulations and public policies that expanded rights in the matter of contraception, comprehensive sexual education, equal marriage and gender identity, using this discourse. In the previous decade, the revolutionary projects that were carried out by political organizations and that defended a part of the left intelligentsia, rejected feminism, the sexual revolution and the "anti-baby pill", understood as bourgeois distractions and weapons of imperialism, that functioned as obstacles to the dedication and commitment demanded by the armed struggle and the strategic need to “give children to the revolution” (Felitti, 2016). Likewise, as Jelin (2017: 70) explains, "in antidictorial practice the nascent paradigm of human rights and women converged, but not as an expression of feminism's demands for equality, but as an expression of the more traditional familism and maternalism" .

As we have already pointed out, the human rights movement that faced State terrorism and continues to demand memory, truth and justice, and the activism for the legalization of abortion materialize their connections with the same distinctive of the scarf. In 2018, some Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo spoke publicly about the need to legalize abortion, participated in the mobilizations, used the green scarf on their wrists and the white ones on their heads, and these knots were explicit, as well as the recognition of these women in a feminine lineage of struggle and rebellion on the part of the youngest (Elizalde, 2018). This happened even with those who did not know in depth the history of the feminists of the 70s, or of the Mothers of the Plaza or of their own, until this opportunity to talk, know and debate was opened in politics, networks, the media, schools and homes. It was in this context that the illustration “Los dos pañuelos” by the Mendoza artist Mariana Baizán went viral and was transferred to T-shirts, pins, stickers, tattoos, graffiti, posters and academic texts like this one. The illustration was published for the first time on Baizán's Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/mariana.dibuja/) in March 2017, within the framework of the Commemoration of March 24, “National Day of Memory, for Truth and Justice ”. It was only with the green tide that the illustration was consolidated as representative of the continuity, specificity and confluence of each struggle, with the demarcation of the territory of each handkerchief.11

Nora Cortiñas, a member of Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo Línea Fundadora, in solidarity with many current struggles, including that of legal abortion, has told the story of the white scarf several times.

It was not until 1980 that we began to wear the white headscarf with the name and surname of the missing relative embroidered. It was on the pilgrimage to the Basilica of Luján, convened annually by Catholic youth. It was our chance: the Basilica was full and, especially, of young people. We had brochures to distribute and in front of so many crowds we had to identify ourselves. It arises at the time as a way of recognizing each other. Actually, when we started using it they weren't a handkerchief but a baby diaper; we all had some at home for our grandchildren. Thus, unintentionally, we founded the symbol of the Mothers (Cortiñas cited in Bellucci, 2000: 284).

Juana de Pargament and Hebe de Bonafini, co-founders and members of the Association Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, have also related what led them to use a diaper to distinguish themselves from the pilgrim crowd.12 This object, associated with parenting tasks that women have historically assumed, jumped the limits of the domestic space and gave them an element of identification with each other and with the world. The political maternalism of the first Argentine feminist wave, which based the claims of civil and political rights on its relational position - we have maternity and maternal obligations, we demand rights as a counterpart - (Nari, 2004) was reconfigured in the 70s and embodied his the motto of the second wave: "The personal is political."

Although in 2018 the presence of girls, adolescents and young people in the mobilizations was thematized as a novelty - known by the feminist press as the "daughter revolution" (Peker, 2019) - it is not a lesser figure than many adult women, between 60 and 80 years old, have actively participated in street mobilizations, sharing the new aesthetic and performative forms brought by the younger ones.

Some pioneers in the struggles for legal abortion and the organization of feminism in the 70s and many others who, without prior political militancy, found an opportunity to demonstrate in the new scenario (Alcaraz, 2018). The festive climate that calls for the dance is distinguished from the fact of denouncing the deaths and the injustice that illegality brings, because what is celebrated is the meeting and the antipatriarchal "incantation" proposed from the own body by "the granddaughters of the witches who they could not burn ”.

Regarding the adoption of the green scarf, María Alicia Gutiérrez, a feminist academic and a member of the Campaign since its inception, explained:

In 2001 there was a huge political and economic crisis in Argentina. The social response is very relevant and the forms of political organization are called into question, the very strong criticism of political representatives, the "let everyone go" and an attempt, through various social organizations, to question the mode of construction of politics and power. The neighborhood assemblies were one of its urban expressions. From that history of struggles, from that assembly spirit, from the recovery of feminist political practices of mainstreaming, the National Campaign for the Right to Safe and Free Legal Abortion emerged in 2005, to fight for the legalization and decriminalization of abortion. It is constituted with more than 300 organizations that support it (today there are more than 500) and with a federal sense. It is a campaign that is developed and expressed throughout the country. The green scarf, a symbol of political demand, was articulated in an important synergy with the scarf of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo and the dimension of human rights (Sánchez, August 1, 2018).

Marta Alanis, founder of Catholics for the Right to Decide Argentina (cdd), current head of Interinstitutional Relations of the association and co-founder of the Campaign, also explained to the press the reason for green: “It is a color that has to do with life: it is used by environmentalists and some health professionals; but at the same time it is a color that does not reflect party identities ”,13 an election that broadens the horizon of interpellation and disputes the characterization of "pro-life" to the anti-legalization groups.

The feminist movement has also made use of the slogan "Never Again", title of the report prepared by the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (conadep) created in 1985 by the government of Raúl Alfonsín (Crenzel, 2008), which condenses the repudiation, resistance and demand for justice against State terrorism. "Never again to clandestine abortion", "Never again alone", and also the association of forced maternity that imposes the illegality of abortion with what has been experienced by the disappeared pregnant detainees, forced to go through their pregnancies and deliveries in clandestine detention centers, whose babies were appropriated as "war loot" (about 500 according to data from the Plaza de Mayo Grandmothers Association) and they were murdered. The sexual and reproductive slavery that Margaret Atwood narrates in her novel The Handmaid's Tale (1985), which is inspired by this section of Argentine history, was staged in some performances artistic artists who added the green scarf for legal abortion to the white cap and the red cape that distinguish the maids of this dystopia.14

Anti-legalization groups also use the discourse of human rights: they present themselves as defenders of life and the rights of the unborn and postulate abortion as a crime against humanity (Faúndes and Defago, 2013; Vacarezza, 2012). It is, in terms of Vaggione (2005), a reactive politicization sustained in languages and arguments that show a strategic secularism: they minimize religious references to draw on international jurisprudence, embryology studies and images of fetal development, and in the case from Argentina and recently in Chile, they try to assimilate the aborted fetus with a “disappeared in democracy” (Felitti and Irrazábal, 2018; Gudiño Bessone, 2017) or a femicide. As in the case of the light blue scarf, these are specular responses that also adopt rules of public spectacularity.

The green scarf: traveling object and transnational symbol

The journey that the handkerchief followed through Latin America was a material and symbolic journey, which responds to particular interests condensed in a specific object and to the logic of transnational circulation of symbols and objects that has been nurtured through the glocalization process (Robertson, 1997). This perspective makes it possible to understand the connections between the global and the local, and reveal the mutual effects that occur in objects and symbols from their circulation. Following De la Torre (2018), the concept of “glocalization” feeds the analysis on how global processes and meanings affect local dynamics and decisions, allows us to look at their movements through transnational networks and circuits and thus study their relocation in the contexts of arrival.

With other antecedents - such as the orange hand used by Uruguayan feminists in 2000, which in Argentina changed its color to green, and which in 2017 arrived in Chile to participate in its debate on non-punishable abortions (Vacarezza, 2019) -, The headscarf adopted in different countries served to make visible a shared restrictive scenario in terms of access to full sexual and reproductive rights and a feminist movement willing to change that situation. It relocated from its territorial context of origin, distinguishing itself as it had already done with the white headscarf of the Mothers and Grandmothers, and it reached other social and cultural settings without the symbol and its meaning losing its original supports. In addition to being a constitutive part of the visual repertoire of the green tide, it acquired an integrating symbolic power by condensing into an easily portable, transportable and reproducible object at low cost, the demand for the right to legal, safe and free abortion in different countries, including Mexico, and the same message: "My body, my decision."

After the first vote in Argentina during June 2018, in Mexico a proposal had been launched to generate a badge equivalent to the green scarf. This initiative promoted by feminist groups, mainly from Twitter, tried to choose a color and a phrase that represented the interests for the legalization of abortion, but the proposals - white or gold scarf - did not have traction or generated identification among users, and even less from organized groups. Finally, it was decided to adopt the green scarf that, by that time, was already installed in the social imaginary as an international symbol for free, safe and gratuitous abortion.

The first time it had a collective and massive presence was in the “Pañuelazo” of August 2018, which responded to an international call to support the crowd that demonstrated in the streets of Argentina while the Chamber of Senators debated and voted on the project .15 The marches were held in different Mexican cities and carried the green scarf as a banner, along with blankets, homemade T-shirts, stencils, stickers, all with messages demanding legal abortion. The response to this call showed that the green tide had come to Mexico to stay, that groups and women - regardless of their identification as feminists - joined the international demand for chosen motherhood and confirmed that the green scarf would be the banner of this struggle.

Discussions about abortion, although not new, were revived in different spaces, including academics. One of the most controversial debates was the "Dialogue around the Right to Decide" held at the Western Institute of Technology and Higher Education (iteso) in September 2018 in the city of Guadalajara.16 The event, organized by the International Relations Students Society and the Public Management and Global Policies Students Society of this institution, summoned experts from civil organizations (cladem, gire and Catholics for the Right to Decide) to discuss the issue of abortion, its legalization and the situation in Mexico. The dissemination poster quickly circulated through social networks and generated great expectations due to the thrust of the context and its headquarters: a Jesuit university. The university received criticism on its social networks from pro-life groups and parents, while the Archbishop of Guadalajara and president of the Conference of the Mexican Episcopate, Cardinal Francisco Robles Ortega, reiterated that he was opposed to abortion and specified that that forum did not have the authorization of the Church.17 With the pressure received, the institution decided, momentarily, to cancel the event on the grounds that there were no security guarantees for its realization.18 This gave rise to student mobilizations in favor of dialogue within the university and it was even considered to hold this dialogue in the Revolution Park, in the center of the city. Finally, the institution agreed to allow it to take place at its facilities, with an advertisement that used the hashtag #itesoYesdialogue,19 and opened the invitation to students, alumni and organizations. The meeting took place in the main auditorium with an audience that exceeded expectations and was broadcast by streaming.20 The rector in turn, the Jesuit priest José Morales Orozco, in his welcome message assured that “the iteso he is for life, he is against abortion, but before that he is in favor of freedom of conscience… No one can judge, only God ”,21 while in the networks, students and society in general celebrated the event and the arrival of the green tide to academic institutions. At streaming and in the multiple publications on social networks, many women and men used the green scarf following the style of the Argentine activists, but they also did so with T-shirts, sweaters or accessories of the color formerly known as “Benetton green” and now identified as “ green abortion ”or“ aborter ”.

A second moment in which the green scarf became visible in Mexico, and in a totally forceful way, was on September 28, 2018 within the framework of the Global Day of Action for a Legal and Safe Abortion. As in the Pañuelazo in August, this march was held in the capital of the country with a massive presence. The women attending, in organized groups, with friends, their partners or on their own, wore green clothes or accessories, among which the green handkerchiefs made by home-made, those with printed white letters made by women's organizations stood out. They sold at a price that covered only the purchase of material and large triangular blankets such as the insignia that led the meeting and its journey through the streets.

The distinctive green color in its different presentations and the handkerchief used in different ways - on the neck, on the wrist, covering the mouth, etc. - caused the curiosity of passers-by who were encountering the Mexican green tide. Why that handkerchief? What phrases is written on it? Now why were the women marching? were questions that were heard several times on the walk. As I found the answers in the pints of the handkerchief and when I heard the slogans - "Abortion yes, abortion no, that's for me to decide" and "Get your rosaries out of our ovaries" - there were signs of both support and rejection.

In the case of Guadalajara, recognized as the second largest city in Mexico as well as one of the most important in terms of the Catholic congregation, the walk of the green tide had several moments of tension that included boos and shouts by men in the street, harassment and threats about "the crime" that was being promoted, the condemnation of the protesters' souls, and even several incidents by elements of the municipal police towards the participants.22

With this demonstration carried out on a national scale and with its media coverage, more and more people, even outside activist and feminist circles, began to associate the green scarf with the movement for the legalization of abortion and its implications: pregnancy / maternity by choice and the right to decide on one's own body. The use of the green scarf not only exceeded the territorial limits that gave rise to it, but also the limits of organized groups identified as feminists. This assembly logic,23 As Álvarez (2019) calls it, it brings together various individual, collective and social, civil and political actors, and is a manifestation of the mobility characteristic of current feminisms. The scarf and its use condensed not only the struggle for a cause that encouraged the (re) assembly of actors of various kinds, but also materialized the solidarity of the global feminist struggle. In this way, both the collective use and its circulation in daily life allowed this symbol to acquire meaning for those who carried it, but it also served as an awareness campaign and dissemination of a political commitment that becomes evident from the materiality of the object. And in turn, following Algranti's (2013) analysis proposal on religious merchandise, beyond a physical geography where the handkerchief circulated from hand to hand, the images and strategies of digital activism expanded the areas of belonging and the arrival of the symbol without it being necessary to share the space in person.

In Argentina, this assemblage was also evident in Congress, when representatives of different political parties came together to gather the necessary votes for the approval of the law and were shown in the debate, which was broadcast by different media, with the green handkerchief in their seats or wrists. In Mexico, the handkerchief acquired another visibility in the media thanks to its presence in the Senate and thus reached social groups that do not participate or follow social networks and whose main vehicle of information is television and radio. On March 7, 2019, several senators placed the green scarf on their seats, which provoked the anger and rejection of Lilly Téllez, senator from Sonora for the National Regeneration Movement party, currently in government, who confronted the senators of the Citizen Movement party for having placed "a green cloth" on his seat without his consent. By naming it that way, he tried to disqualify the symbol by associating it with a discarding element, without considering that the rag is also a cleaning and working tool for millions of women. The versatility of the emblem was once again on display. In the videos and notes that circulated through the network and the media, Senator Téllez was shown holding the handkerchief with rejection and saying:

Putting a green cloth on my seat makes other women and citizens think that I support abortion, when I am against it. I ask that just as I am not going to tear a green cloth from your neck, you do not come and put a green cloth on my seat, which for me means death. I represent many people who believe that abortion is the murder of a person. Furthermore, I invite the senators who are against abortion to support me in presenting something similar to what the Nuevo León congress did, I support what they did and congratulate the Nuevo León congress.24

This fact, which circulated for several days in the press and the media at the national level, enabled the debate on legal abortion and on the use of the green scarf, taking it to other audiences. The reactions provoked by their presence in the seats showed that the current party in power and its representatives - who are the majority in Congress - defend a conservative political agenda with respect to reproductive rights - among others -, as we observed before when referring to the law passed in Nuevo León. This situation, added to the discussions on same-sex marriage, among others, has once again placed the validity and state of secularism in Mexico on the public and academic agenda.

By way of closing

The green scarf proposed as a distinctive by the National Campaign for Legal, Safe and Free Abortion in Argentina is today a banner of the feminist struggle in the region and a sign of identification capable of awakening differentiated affections and emotions. Pride, security, hubbub, fear, rejection, anger, contempt, are some of the feelings associated with this symbol, which went from an extraordinary use restricted to specific dates, a body space and a country, to multiplying its presence in daily life, to be used in different parts of the body, to go through the space tied to the strap of a bag or suitcase, to be fixed on the grill of a window or the craft beer dispenser in a bar, and above all, to be a traveler symbol between different countries. The green scarf is a public and proud expression of support for legal abortion, it shows love and sisterhood when it is a gift, it is a source of income for those who make and sell it, it signals confidence and security when we find it in the night walk alone in Another backpack, outrageous when whoever wears it does not honor social justice or work to bring down the patriarchy, and it is a distinctive that we prefer to hide if we anticipate the stalking of sexist violence or if we think that it will be a barrier to starting a conversation that Help deconstruct gender stereotypes.

Its widespread use in national, physical, political and gender, class and age territories materialized the assembly of a feminist solidarity at unimagined levels. In a scenario of global and transnational circulation of the slogans, from "Not One Less" to "MeToo", which rely on the power of convocation and mobilization of social networks, the green scarf - or the green scarf, as it is called. llama in Mexico - is a tangible and visible sign that suspends discussions within the movement on issues such as commercial sex, pornography, the privileges of white middle-class women, and segregationist positions regarding transsexuality. This symbol invites the (re) articulation of various individual and collective actors, and proposes a margin of agreement and consensus without denying particularities or silencing differences.

With a speed greater than that which could occur in the 70s and 80s, when the travelers carried and brought books, magazines, ideas and debates, and the Argentine exiles became feminists in Mexico, an object of simple confection - key to their success as an emblem - it expands without limits other than those imposed by the groups against legalization, who speculate (re) create their symbolism (light blue scarf) and slogans (It is not No), they exacerbate the plebiscite and the idea of consensus; and in the case of Argentina, they are inserted in the debates on recent history and human rights.

The handkerchiefs are the main elements of the green tide, the insignia that represents and synthesizes the fight for human rights, reproductive rights and the protection of the State to the reproductive decisions of women and people with the capacity to bear children. They are combined with green accessories, violets, the orange kerchief of the secular state and the glitter that since August 2019 it is not only green, as shown by the presence of the pink diamond in the mobilizations in Mexico in reaction to the lack of response of the authorities to gender violence and the fact that the security forces themselves are the who attack and rape women.

The way of wearing the scarf marks a generational belonging, which refers to the renewal of feminism, of new waves that, beyond aesthetics - and also based on it -, have renewed the way of doing politics from the channels used to the performative display. Seeing the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo raise the green scarf, speak with inclusive language and take to the streets without age being a brake confirms them as predecessors who follow their agenda and at the same time open up to new needs, expressions and movements . From this position, they bring together the demands for legal abortion, social justice, the restitution of the identity of each appropriate grandchild, the common jail for each genocide and the end of the repression of the security forces in the same Act, with the same symbol, that changes color and body location but maintains and duplicates the political and affective identification that it claims: not one more death due to a clandestine abortion or sexist violence and the bodily sovereignty of all people.

Bibliography

Alcaraz, Florencia (2018). ¡Que sea ley! La lucha de los feminismos por el aborto legal. Buenos Aires: Marea Editorial.

Algranti, Joaquín (ed.) (2013). “Introducción”, en La industria del creer. Sociología de las mercancías religiosas. Buenos Aires: Biblos.

Altamirano, Claudia (2018). “La marea verde en la cdmx: mujeres marchan por la legalización del aborto en México”, en Animal Político. Recuperado de https://www.animalpolitico.com/2018/09/marea-verde-mujeres-marcha-aborto/, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Álvarez, Sonia (2019). “Feminismos en movimiento, feminismos en protesta” en Revista Punto Género, núm. 11. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-0417.2019.53881

Ángel, Arturo (2019). “En México se abrieron más de 2 mil casos penales por aborto, desde 2015”, en Animal Político. Recuperado de https://www.animalpolitico.com/2019/03/mexico-casos-penales-aborto/ consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Animal Político (2018). “Abortar en México: ¿en qué estados se criminaliza más a las mujeres por interrumpir el embarazo?”, en Animal Político. Recuperado de: https://www.animalpolitico.com/2018/08/abortar-mexico-mujeres-estados/, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Arquidiócesis de Monterrey (2018). “Cardenal Robles Ortega no autorizó evento a favor del aborto en el iteso”, en Arquidiocesisdemty.org. Recuperado de https://www.arquidiocesismty.org/arquimty/cardenal-robles-ortega-no-autorizo-evento-a-favor-del-aborto-en-el-iteso/, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Bellucci, Mabel (2000). “El Movimiento de Madres de Plaza de Mayo”, en Fernanda Gil Lozano, Valeria Silvina Pita y María Gabriela Ini (comp.), Historia de las Mujeres en la Argentina, Siglo xx, t. ii. Buenos Aires: Taurus, pp. 266-287.

Bellucci, Mabel (2014). Historia de una desobediencia. Aborto y feminismo. Buenos Aires: capital intelectual.

Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina (2019) Ministerio de Salud. Resolución 1/2019RESOL-2019-1-APN-MS. Recuperado de https://www.boletinoficial.gob.ar/detalleAviso/primera/223829/20191213, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Burton, Julia (2017). “De la Comisión al Socorro: trazos de militancia feminista por el derecho al aborto en Argentina”, en Descentrada, vol.1, núm. 2. Recuperado de: http://www.descentrada.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/DESe020, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Canal Encuentro (2015). Madres de Plaza de Mayo. La historia: los pañuelos (video). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJA-vXiZ5Ks, consultado el 21 de enero de 2020.

Carbajal, Mariana (2018). “El pañuelo verde, el símbolo”, en Página 12. Recuperado de: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/121322-el-panuelo-verde-el-simbolo, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Castillo, Gabriela (2018). “La larga y complicada historia de un foro sobre aborto en el iteso”, en Plumas Atómicas. Recuperado de https://plumasatomicas.com/noticias/mexico/aborto-foro-derecho-decidir-iteso/, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Crenzel, Emilio (2008). La historia política del Nunca Más. La memoria de las desapariciones en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Siglo xxi.

Dulbecco, Paloma y Daniel Jones (2018). “Lxs evangélicxs ante los derechos sexuales y reproductivos; más allá de la reacción conservadora”, en Sociales en Debate, núm. 14. Recuperado de https://publicaciones.sociales.uba.ar/index.php/socialesendebate/article/view/3347, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Elizalde, Silvia (2018). “Hijas, hermanas, nietas: genealogías políticas en el activismo de género de las jóvenes”, en Ensambles, vol. 4, núm. 8, pp. 86-93. Recuperado de http://www.revistaensambles.com.ar/ojs-2.4.1/index.php/ensambles/article/view/149, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Faúndes, José Manuel Morán y María Angélica Peñas Defago (2013). “¿Defensores de la vida? ¿De cuál vida? Un análisis genealógico de la noción de vida sostenida por la jerarquía católica contra el aborto”, en Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad, núm. 15, pp. 10-36. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-64872013000300002

Felitti, Karina y Gabriela Irrazábal (2018). “Los no nacidos y las mujeres que los gestaban: significaciones, prácticas políticas y rituales en Buenos Aires”, en Revista de Estudios Sociales, núm. 64, pp. 125-137. https://doi.org/10.7440/res64.2018.10

Felitti, Karina (2018). “Las chicas del pañuelo verde en las escuelas religiosas: sentidos en disputa más allá de la laicidad estatal”, en Sociales en Debate, núm. 14. Recuperado de https://publicaciones.sociales.uba.ar/index.php/socialesendebate/article/view/3354, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Felitti, Karina (2016). “Maternidades y militancia en la Argentina de los 70. Notas históricas para pensar las maternidades colectivas contemporáneas”, en Revista de Historia Regional, vol. 21, núm. 2, pp. 432-458. https://doi.org/10.5212/Rev.Hist.Reg.v.21i2.0006

Forbes (2019). “Nuevo León prohíbe el aborto con derecho a la vida desde la concepción”, en Forbes. Recuperado de https://www.forbes.com.mx/nuevo-leon-prohibe-el-aborto-con-derecho-a-la-vida-desde-la-concepcion/, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Frigerio, Alejandro (1999). “Estableciendo puentes: articulación de significados y acomodación social en movimientos religiosos en el Cono Sur”, en Alteridades, vol. 9, núm. 18, pp.5-18.

Gómez, Carolina (2018). “Aborto legal en todo el país, exigencia en la marcha de ayer”, en La Jornada. Recuperado de https://www.jornada.com.mx/ultimas/2018/09/29/aborto-legal-en-todo-el-pais-exigencia-en-la-marcha-de-ayer-279.html , consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Grupo de información en reproducción elegida (gire) (2019). Hoy, los y las diputados de Hidalgo le fallaron a las mujeres. La democracia les queda a deber a las hidalguenses. #AbortoLegalHidalgo #SeraLeyHidalgo [Actualizacion de estado de Twitter]. Recuperado de https://twitter.com/GIRE_mx/status/1205186120520290307?s=20, consultado el 21 de enero de 2020.

Grupo de información en reproducción elegida (gire) (2018). Maternidad o castigo. La criminalización del aborto en México. México: Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida, A.C.

Grupo de información en reproducción elegida (gire) (2017). Violencia sin interrupción. México: Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida, A.C. Recuperado de https://aborto-por-violacion.gire.org.mx/assets/pdf/violencia_sin_interrupcion.pdf, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Grupo de información en reproducción elegida (gire) (2008). “La despenalización del aborto en la ciudad de México”, en Debate Feminista, vol. 38, pp. 3-8. Recuperado de http://www.debatefeminista.cieg.unam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/articulos/038_01.pdf, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Gudiño Bessone, Pablo (2017). “Activismo católico antiabortista en Argentina: performances, discursos y prácticas”, en Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad. Revista Latinoamericana, núm. 26, p. 38-67. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-6487.sess.2017.26.03.a.

Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (iteso) (2018). “A la comunidad universitaria del #iteso, sobre la suspensión del diálogo “Por el derecho a decidir” @alumnositeso @itesoegresados @Politicas_iteso” [Actualización de estado en Twitter]. Recuperado de: https://twitter.com/ITESO/status/1044734133099003905/photo/1, consultado el 21 de enero de 2020.

Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (iteso)(2018, 26 de septiembre). Diálogo por el derecho a decidir. Recuperado de: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJA-vXiZ5Ks, consultado el 24 de enero de 2020.

Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (iteso)(2018, 26 de septiembre). “#itesoSÍdialoga El foro “El derecho a decidir” se llevará a cabo en el Auditorio Pedro Arrupe, sj, hoy, a las 4pm. #HablemodePaz @Politicas_iteso @alumnositeso @itesoegresados” [Actualización de estado en Twitter]. Recuperado de: https://twitter.com/ITESO/status/1045017351610142721/photo/1, consultado el 21 de enero de 2020.

Jelin, Elizabeth (2017). Las luchas por el pasado. Cómo construimos la memoria social. Buenos Aires: Siglo xxi.

Nación 321 (2019). “Lilly Téllez: yo creo que el aborto sí es el asesinato de una persona”. Recuperado de https://www.nacion321.com/congreso/lily-tellez-yo-creo-que-el-aborto-si-es-el-asesinato-de-una-persona, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Nari, Marcela (2004). Políticas de maternidad y maternalismo político. Buenos Aires, 1890-1940. Buenos Aires: Biblos.

Maier, Elizabeth (2008). “La disputa por el cuerpo de la mujer, la/s sexualidad/es y la/s familia/s en Estados Unidos y México”, en Frontera Norte, vol. 20, núm. 40, pp. 7-47. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/136/13624001.pdf, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Morcillo, Santiago y Karina Felitti (2017). “‘Mi cuerpo es mío’. Debates y disputas de los feminismos argentinos en torno al aborto y al sexo comercial”, en Amerika, núm. 16, pp. 1-15. https://doi.org/10.4000/amerika.8061

Muñiz, Erick (2019). “Congreso de Nuevo León aprueba penalización del aborto”, en La Jornada. Recuperado de https://www.jornada.com.mx/ultimas/2019/03/06/mujeres-que-aborten-iran-a-la-carcel-en-nuevo-leon-6386.html, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Padilla, Jesús (2019). “Nuevo León: sin aborto legal”, en Reporte Índigo. Recuperado de https://www.reporteindigo.com/reporte/nuevo-leon -sin-aborto-legal-congreso-reforma-polarizacion-legisladores-activistas/, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Pecheny, Mario, Daniel Jones y Lucía Ariza (2016). “Sexualidad, política y actores religiosos en la Argentina post-neoliberal (2003-2015)”, en Macarena Saéz y José Manuel Morán Faúndes (ed.), Sexo, delitos y pecados: intersecciones entre religión, género, sexualidad y el derecho en América Latina. Washington: Center for Latin American & Latino Studies American University, pp. 53-90. Recuperado de https://www.american.edu/centers/latin-american-latino-studies/upload/3-15-17-SEXO-DELITOS-PECADOS-3-0.pdf, consultado el 22 de enero

de 2020.

Pecheny, Mario (2010). “Parece que no fue ayer: el legado político de la Ley de Divorcio en perspectiva de derechos sexuales”, en Roberto Gargarella, María Victoria Murillo y Mario Pecheny (comp.), Discutir Alfonsín. Buenos Aires: Siglo xxi, pp. 85-113.

Peker, Luciana (2019). La revolución de las hijas. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Radi, Blas (2018). “Mitología política sobre aborto y hombres trans”, en Sexuality Policy Watch. Disponible en https://sxpolitics.org/es/3945-2/3945, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Ramírez, María del Rosario (2018). “Narrativas religiosas y aborto legal”, en Carlos Garma, María del Rosario Ramírez y Ariel Corpus (coord.), Familias, iglesias y Estado laico. Enfoques antropológicos. México: Departamento de Antropología-uam Iztapalapa/Ediciones del Lirio, pp. 135-154.

Ramón, Agustina y Soina Ariza (2018). La legalidad del aborto en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: ela/redaas/cedes. Recuperado de http://www.redaas.org.ar/archivos-actividades/129-LEGALIDAD%20DEL%20ABORTO%20-%20ARM%20y%20SA.pdf, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Ramos, David (2018). Arzobispo de Guadalajara a universidad jesuita: No al aborto, en aciprensa. Recuperado de https://www.aciprensa.com/noticias/arzobispo-de-guadalajara-a-universidad-jesuita-no-al-aborto-76005, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Recamier, Mariana (2018). “Mexicanas se movilizan para pedir aborto legal en Argentina”, en Reporte Índigo. Recuperado de https://www.reporteindigo.com/reporte/mexicanas-se-movilizan-pedir-aborto-legal-en-argentina/, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Ríos, Lucía (2018). “Campaña provida: ¿cómo nació el pañuelo celeste?”, en Télam. Recuperado de https://www.telam.com.ar/notas/201805/281613-panuelo-celeste-provida.html, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Robertson, Roland (1997). “Glocalización tiempo-espacio y homogeneidad-heterogeneidad”, en Juan Carlos Monedero (coord.), Cansancio del Leviatán: problemas políticos de la mundialización. Madrid: Trotta, pp. 261-284.

Roger, Elena y Las Criadas (2018). “Acción por el aborto”, en Página 12. Recuperado de https://www.pagina12.com.ar/130835-accion-por-el-aborto, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Torre, Renée de la (2018). “Itinerarios teóricos metodológicos de una etnografía transnacional”, en Revista Cultura y Representaciones Sociales, vol. 12, núm. 24. https://doi.org/10.28965/2018-024-02

Vacarezza, Nayla (2019). “Manos y pañuelos. Contagios políticos y derroteros transnacionales de dos símbolos a favor del aborto legal en el Cono Sur”, ponencia presentada en lasa 2019, Boston, Estados Unidos, 24-27 de mayo.

Vacarezza, Nayla (2012). “Política de los afectos, tecnologías de visualización y usos del terror en los discursos de los grupos contrarios a la legalización del aborto”, en Ruth Zurbriggen y Claudia Anzorena (comp.), El aborto como derecho de las mujeres. Otra historia es posible. Buenos Aires: Herramienta, pp. 209-226.

Vaggione, Juan Marco (2005). “Los roles políticos de la religión. Género y sexualidad más allá del secularismo”, en Marta Vasallo (ed.), En nombre de la vida. Buenos Aires: Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir. Córdoba: Edición Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir, pp. 137-167.

Sánchez, Ana (2018). “Pañuelos verdes: una historia de lucha feminista. Entrevista a María Alicia Gutiérrez, Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal Seguro y gratuito en Argentina”, en Diario El Salto. Recuperado de https://www.elsaltodiario.com/vidas-precarias/entrevista-a-maria-alicia-gutierrez-campana-nacional-por-el-derecho-al-aborto-legal-seguro-y-gratuito-en-argentina, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Santoro, Sonia (2018). “La onda sigue verde”, en Página 12. Recuperado de https://www.pagina12.com.ar/144025-la-onda-sigue-verde

Suárez, Hugo José (2008). “La fotografía como fuente de sentidos”. Cuaderno de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 150. San José de Costa Rica: flacso Costa Rica/Asdi.

Sutton, Bárbara y Elizabeth Borland (2017). “El discurso de los derechos humanos y la militancia por el derecho al aborto en la Argentina”. Trabajo presentado en Horizontes revolucionarios. Voces y cuerpos en conflicto. xiii Jornadas Nacionales de Historia de las Mujeres. viii Congreso Iberoamericano de Estudios de Género, 24 al 27 de Julio 2017.

Télam (2019). “Día Internacional de la mujer: 8M minuto a minuto”. Recuperado de http://www.telam.com.ar/cobertura-en-vivo/33/dia-internacional-de-la-mujer-el-8m-%20minuto-a-minuto, consultado el 22 de enero de 2020.

Zurbriggen, Ruth y Claudia Anzorena (comp.) (2013). El aborto como derecho de las mujeres. Otra historia es posible. Buenos Aires: Herramienta.

[…] Pour le droit à l'avortement (the foulard vert is brandi par les partisans de l'avortement, even if it ignores the origin precise de ce symbole) s'inscrit pleinement dans les mobilisations récentes dans le pays, et notamment celles, très […]

[…] Rich slogans, with their symbols (the green scarf is brandished by supporters of abortion, although the exact origin of this symbol is unknown), is fully inscribed in the recent mobilizations in that country, and in particular in the very […]