A new breed open to the future: Melchor Peredo's mural in La Antigua

Interview with

*

Receipt: March 10, 2025

Acceptance: April 07, 2025

was born in Mexico City in 1927. He is recognized as the last representative of Mexican muralism among scholars. His vast work, developed over more than seven decades, can be found in several emblematic buildings in Mexico, France and the United States. For the last four decades he has lived in Xalapa, where most of his mural work is concentrated in the municipal palace, the Superior Court of Justice and spaces of the Universidad Veracruzana. He mainly uses the fresco technique and developed an innovative method of applying murals on cement sheets. He has reconciled his artistic work with university teaching, transmitting his knowledge to new generations. He is the author of Xalapa, stronghold of the Mexican muralist revolution (2015) y Los muros tienen la palabra (2019).

Based on the research work we have been doing since 2021 with the Universidade Aberta in Lisbon (uab), related to the adaptability of Portuguese immigrants in Mexico, we have found that an increasing number of Mexicans join the Portuguese community by naturalization due to their origins as Sephardic Jews from the colonial era. As Miguel León-Portilla mentions, this phenomenon is the result of the relationship between Portugal and Mexico since the xviAlthough little known, their presence has endured in various forms over time. This fact awakened our interest in delving deeper into the subject and, with the aim of creating new lines of research, we undertook a project in collaboration with the Department of History to study the presence and influence of Portuguese Jewish converts in the shaping of New Spain. On one of our fieldwork trips to La Antigua, Veracruz, we came across the mural titled A new breed open to the futureThis led us to hypothesize whether its author, Melchor Peredo y García -a renowned Mexican muralist- had considered the arrival of the Portuguese who arrived with Cortés.

Master Melchor Peredo was born in Mexico City in 1927; from an early age he decided to become an artist, influenced by Mexican muralism, which is clearly reflected in all his work. This movement emerged after the Revolution of 1910, based on socialist and nationalist ideals, and is characterized by its protest against social intolerance towards minorities -the indigenous, the peasant or the proletariat-, thus seeking to rescue the dignity of the working class, highlighting the exploitative conditions in which they lived and exposing the complex power relations within society.

By advocating the cause of the oppressed against the oppressor, muralism is defined as a political, social and cultural project, representing the principles of socialism; the apology for the progress of science and knowledge; and, later, with the use of its powerful indigenous iconography, it recovers the identity roots of the Mexican people, acting simultaneously as a vehicle for the vindication of the past and as a form of resistance in the present. Likewise, the movement reflected the criticism of the wars and, above all, of the Eurocentric narrative that had prevailed in the history of Mexico; it also sought to have an impact on reestablishing the historical truth in relation to the conquest and colonization and, mainly, on the War of Independence and the Mexican Revolution.

The art of muralism not only made visible themes different from those instituted at the time, but also created an innovative aesthetic and technical repertoire. In addition, it assumed a pedagogical function, distinguished by communicating from the public space -government buildings, schools and universities-, taking advantage of the monumentality of its works. Undoubtedly, the muralist movement positioned Mexico in the international cultural vanguard by granting it the prestige of a "Mexican Renaissance", as stated by maestro Melchor Peredo in this interview.

Among the most famous names of the century xxThe artists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco are fundamental pillars of this movement, a legacy that Melchor Peredo fully embraced, which has led him to be recognized as the last representative of Mexican muralism among scholars. His vast body of work, to which he has been dedicated for more than seven decades, is exhibited in various emblematic buildings in Mexico and in other countries, such as France and the United States. However, Xalapa was the city he chose as his home decades ago, and it is there where the greatest concentration of his works can be found in different buildings, such as the municipal palace of Xalapa, the Superior Court of Justice of Xalapa, spaces of the Universidad Veracruzana and many other buildings in the state of Veracruz.

The master uses fresco as his main technique, but his creativity led him to develop a new method that allows the application of murals on cement sheets or ceilings, which facilitates the mobilization of the works to be exhibited in different places. In addition to his work as an artist, he has reconciled teaching as a professor in several universities, with a firm commitment to the artistic education of new generations, dedicating himself to transmitting his knowledge, especially through the workshops he has taught at the Universidad Veracruzana in recent decades.

He is the author of several books, including Xalapa, stronghold of the Mexican muralist revolutionin which he made a compilation aimed at making visible the murals about the Mexican Revolution with the greatest impact. His work can also be found in Los muros tienen la palabrawhich brings together some of the chronicles he wrote over a five-year period for the newspaper Xalapa NewspaperAs Lourdes Hernández Quiñones points out in the presentation of the book, his articles deal with art, historical accounts and the social and political commitment of the artist.

In this sense, we conducted an interview with Maestro Melchor on July 26, 2024 via videoconference, through Microsoft Teams, which lasted a little over an hour; he was accompanied by his wife, Lourdes Hernández Quiñones. During the chat he shared with us the historical and cultural significance behind the mural. A new breed open to the future. He also addressed the importance of representing Mexican identity through muralism, exploring the movement's influence on his art, and confessed that his ultimate purpose in art is to challenge historical lies and foster a deeper understanding of history; he offered us a reflection on the relevance of mural art in education and Mexico's cultural identity, as well as advising young muralists to stay true to their cultural roots and highlighting the role of art as a means of cultural resistance and the search for truth.

Maestro Melchor, during our visit to La Antigua, we had the privilege of observing your double-sided mural titled A new breed open to the futureCould you share with us what was the purpose behind this work and what inspired its creation?

It is a bit of a special story, let's say a bit picturesque, because the governor at the time was Miguel Alemán, a young man, and someone recommended that I paint a mural of the sixteen horses that had come with Hernán Cortés. Curiously, all the names of those horses are described in the chronicles. So, I am very fond of, and more than that, I get very involved in the history of the subjects I have to paint. Because I have the conscience that there are many lies, and that those things that are taught and those that are not taught, have falsehoods and lacks, the textbooks, etcetera. Even university people have a lot of misinformation. I do not pretend to know more than others, but I have very good friends here with several historians, eminences like Carmen Blázquez and others. Also, what I could see in the chronicles, it turns out that it was possible to make a series of horses. But I like to say, it seems ridiculous to me [laughs], what do those horses have to do with it? Besides, it doesn't say anything, a horse, a cavalry, if it were a stable, right? Well, plus a place like La Antigua, the third place where it sits.

The first town, the city of Vera Cruz de la Veracruz, they don't like it because there are many diseases, and they go to what is now called Villa Rica, which is a small town. There they founded cities in their own style; the first thing they did was to put a pillory [he laughs]. They even cut off the feet of a soldier because he said he wanted to return to his land: "And nobody leaves me here, I'm going to sink the ships of all of them, so that nobody can return" [laughs].. Smart man, I'm talking about Hernán Cortés, because he leaves a little boat, right? [he laughs], so he has to leave.

Afterwards, they finally went to Mexico and carried out the barbaric destruction of Tenochtitlan in the marvelous city. And on their way back, they settled for several years in this place called La Antigua, where a river called de los Pescados (Fish River) flows into the sea.. There, ships begin to arrive from different parts, from Central America, Spain and Portugal and slaves; people of many origins disembark. In my latest murals I represent, precisely, the scene in which they are unloading the raw material to build a city, which is human flesh, which are the slaves.

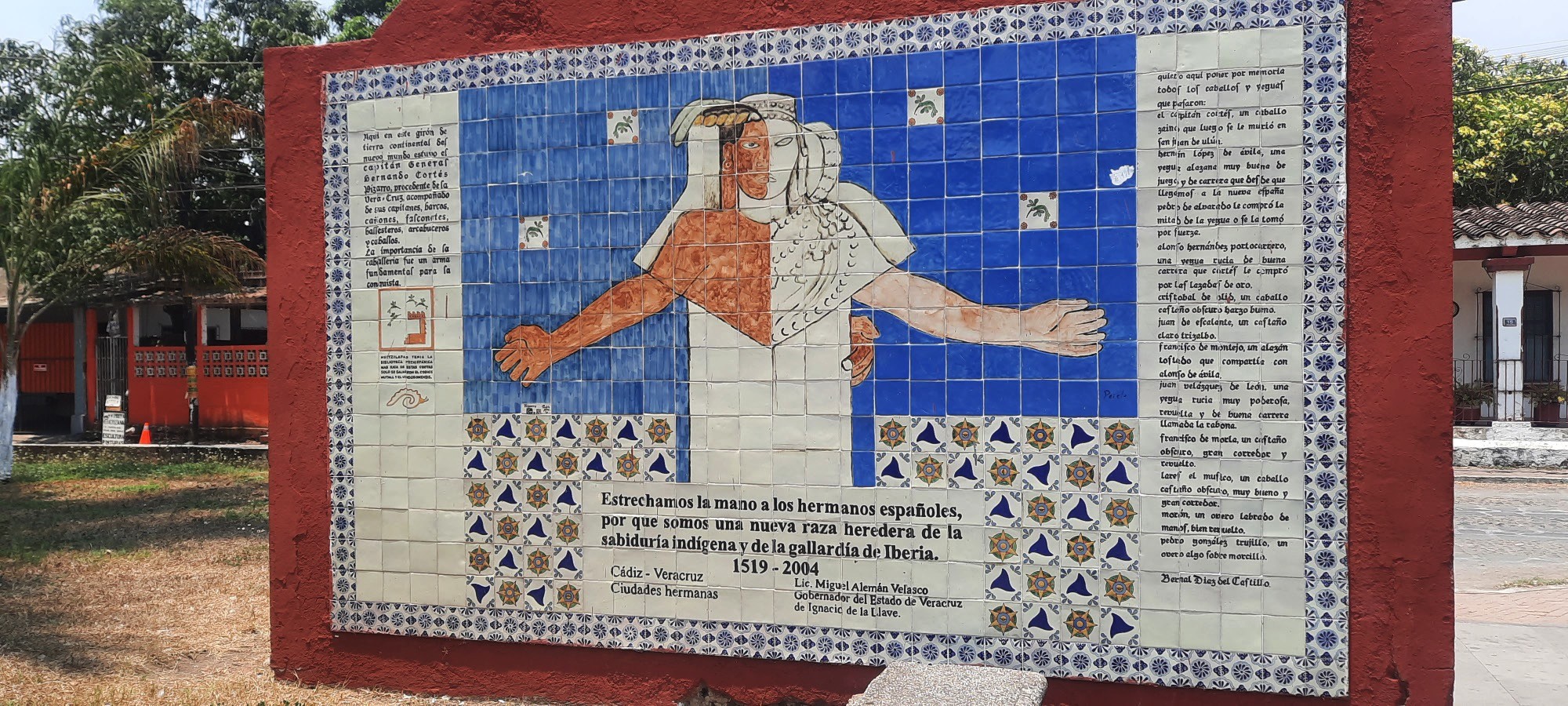

So, I said to myself: "Well, let's make a list of these horses with names, which are registered", and over there, on the other side, there was the list of names. But I said to myself: "How I like it when they give me subjects that I find questionable"; I like, excuse me for saying it, but I like to make fun of people [laughs]. So, I said: "Well, the horses, but yes, with their riders", and those riders seem very ugly, very aggressive, don't they? [laughs]. Terrible, isn't it (see image 1). As we know, history tells us, the Indians thought that man and animal were one animal; they were centaurs, they were quite terrible for the Indians. That's why there are those little horses there, so they're kind of diabolical; I had a lot of fun doing that.

So, the purpose of your work was to commemorate the historical relations between Mexico and Spain. Yes, we notice that the image of the horses is striking, while the back offers a certain enigma. Could you elaborate on how these two murals reflect such different symbolisms?

This mural was commissioned by the governor of Veracruz. How kind of Miguel Alemán to commission this work from me! [he laughs]. I have already made the list of the little horses, but now, for this, I am going to give him a mural, and on the back, which is the back of this one, there is another mural of the same size also made with talavera-type mosaic.

Since it was about receiving a group of Spaniards who were going to be there, the governor wanted to receive them well and invited historians like [Miguel] León-Portilla. We were there, people interested in history. I said to myself: "Well, I'm going to paint something positive, something that I feel, that I believe in"; and it is that dramatic, deep dispute that still survives: that if we are Spanish, or if they are Mexican Indians, or who were the bad guys or who were the good guys [he laughs]. That is why I put the title, we are a new race, a combined race, a race rich in elements of art and culture, and it is open to the future, that is to say, it is yet to happen, to be seen, and that is why it is called that way.

Graphically, I wanted to represent two elements: one is the lady of Elche of Spanish archaeology, which is so important and beautiful; and the other half of the same figure is constituted by an Indian seen in profile. That is to say, it is a combination of two figures that make one (see image 2). And excuse me, but no matter how much I do, I can't stop being a joker [he laughs]. The man is doing part of the woman, but he has his hand on her hip [laughs]. When the governor arrived, he saw that man taking the hip of the lady of Elche, well, yes, they were doing race, right? [he laughs]. The governor just looked at him, smiled, and took it well; these are very Mexican things, we put aside the mischief. Now I see that he has an earth-colored frame, brown, he didn't have it; I'm sorry. And that is how that name came about, and it was with all my heart. I insist on this thesis because yes, we can't go on fighting brown people with white people, nor green people [he laughs].

This mural, as you mentioned, stands out for its talavera mosaic technique, which is a different and distinctive approach to your usual work. What led you to choose this technique, especially considering the difficulties that working with pigments can entail? How was your experience in creating this work?

Yes, it is made of talavera. It happens that, in different cities and towns in Mexico, for historical reasons sometimes difficult to discern, an industry is created, a craftsmanship specific to that place. I do not know why Puebla was the place where this taste for mosaics grew; it is probably due to the type of very resistant materials used. Perhaps because in Puebla many churches were built, this material makes sense in churches, because of its resistance; and in other towns in Mexico there was not so much strength of the Christian religion, so they gained this custom.

These special muds are put in a tank and with the feet they are kneaded until they are perfectly clean; and then that value is converted into this type, like porcelain. The work was done in Puebla, I mean, it was made by me, it was painted by me, but it was baked, each mosaic was put in the oven by some very renowned artisans from Puebla. Really, for me it was an adventure, because I don't know if you have worked or know how mosaic is made; there are some colors, they are all the same color, they are like little gray powders and only when they are fired do they acquire their color. So, we were calculating, what if this is green, what if this is blue, what if this is red, right? And it's an adventure, now yes, it's not very, very easy. These workers made their stew, by the way, and the way things are now, later, when they came to participate in the inauguration, they were not allowed to enter [he laughs]. Each participant had painted on the floor where they were going to stand, didn't they, for safety reasons [he laughs].

As we mentioned, our visit to La Antigua was focused on the interest of learning more about the presence of the Portuguese who arrived with Cortés. Throughout your research, have you found any information or accounts of the influence of these Portuguese in shaping Mexico's cultural identity?

You can see the list here, what I say here this "new race". What does it say here? "We shake hands with our Spanish brothers, because we are a new race, heir to the indigenous wisdom and the gallantry of Iberia 1519-2004.". And you ask me: "Well, ¿and this Where did you get this text?". The truth is that they asked the governor: "Hey, what are you going to write over there? Tell me, governor, what do you want the painter to say?". [The governor replied] "Let him write whatever he wants, let him write whatever he wants" [he laughs]. The confidence is appreciated and this is the history of this site.

I think you must know a sensational book by Úrsula Camba Ludlow, called Echoes of New Spain: Mexico's lost centuries in historyThere is a biography of each and every one of them and, in addition to their full names, curiously, their signatures also appear. This means that they were not as ignorant as many people think they were barbarians, right? They all knew how to sign [laughs]. That book is fabulous; the author came here to Xalapa to present it. And there, we can see, as you say, who were of Portuguese origins, etcetera. In addition to the Spanish ships, many Portuguese ships arrived in La Antigua, because it was a place on the outskirts where they could anchor their ships at the river's exit.

I don't know if you were in contact with Bernardo García Díaz who has done a lot of research on this subject; with another researcher, I think they are studying precisely about the Portuguese, because he asked me for that book that I had; but I gave it as a gift to a great researcher, Carmen Blázquez.

So they arrived with Hernán Cortés, who first arrived at Villa Rica, and he told them: "You are not going back to me; here you came and here you stay"; and that is why he sank the ships, he did not burn them, as many people think; he sent the captains at night to sink them. We have a small cabin, precisely in Villa Rica, right in front of where the French are, divers are finding anchors and part of their ships.

You are an emblematic figure of muralism in Mexico. What are your main sources of inspiration and how have they influenced the representation of Mexican identity in your works?

The painters here in Mexico have their roots in the pre-Hispanic past; the marvelous art of the Olmecs, above all; and from there Mexican painting has grown under the name of Mexican Muralism, with a capital letter. It even made a lot of noise in the world, it was very important. Now yes, there were many people of pure indigenous race, but outside there were not many painters, there were few who made that Mexican Muralism and we would say that they are counted.

Look, we had a Revolution in 1910 because the rulers, Porfirio Diaz, was a very chicthe French way. Of course, with good reason, France was a wonderful thing; but there were many Spaniards, also hacienda owners, who were heirs of the conquistadors. The conquistadors had arrived and enslaved the Indians; later, when the haciendas were formed, they turned them into workers, sometimes without pay, almost like slaves. This whole situation of contempt for the indigenous was very Hispanic, in the Spanish style, which was the Europeanizing style of Porfirio Díaz.

There comes a moment when [Emiliano] Zapata stands up, grabs his rifle and says: "We are Mexicans" [he laughs]; and Pancho Villa comes: "We are Mexicans", and the painters come and say: "Ah, well, we are going to make art based on pre-Hispanic art as well". Then, a man, Diego Rivera, who all his life was working to rescue the cultural artistic values of the pre-Hispanic era, came along. To the extent that, before he died, he built an enormous building which is the Anahuacalli or the house of the temple of America, with the materials and the type of culture used for the pyramids, a marvelous thing. He built it enormous, he did it to keep about two thousand archaeological pieces that he had gathered with all his love to set up his museum.

They, above all he, was the one who most sought this rescue, and all this was the nationalist movement, which was called, and the Mexican renaissance. From there came artists such as [Silvestre] Revueltas; the musician with music with very similar tones also linked to the drama of sound, to the spirit of Mexico. A very Mexican cinema arises, based on Mexicanness, a Mexicanness that at times is a little curious because it empowers the figure of the charro, but the charro is of Spanish origin [he laughs].

There was a very, very unfriendly critic who said: "In Mexico there is nothing more than the murals of Diego Rivera"; that here in Mexico there is nothing more than the murals. And, certainly, it was the moment of culture that was growing, what was called the golden age, in cinema, music, literature and painting, all with respect for the strength and depth of pre-Hispanic times.

Then comes a moment when, it must be said, there is an intrusion by the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).cia), during the Cold War, yes? And Mexican art had to suffer very well-planned attacks to discredit it; and the time came when it was a sin to paint Mexican things, a sin to make Mexican music [he laughs]. All this is a long story, which should be told, not a justification, but an explanation; there were atomic bombs on one side and on the other, and they didn't want anyone in Mexico to think about nationalism.

So, in the face of these external pressures and expectations, how did you manage to resist and stay true to your artistic vision?

I want to give a tangible answer, an answer on paper. That moment when our culture is attacked, is distorted for these dirty, political reasons. And, you ask me what to do or if someone did something? I don't want to be pretentious, but I was born in Mexico City and I refused to give in to that invasion of purist art, etc., that came from the United States. I started to work in the same line of nationalism, but a nationalism that criticizes you, and I wrote a book: Xalapa, stronghold of the Mexican muralist revolution of 2015.

Since I arrived here [nearly 40 years ago] [Xalapa], we have managed to continue a critical and somehow revolutionary line because we do not accept lies. Also, it must be said, at one point our great master Diego Rivera told us: "Boys, don't paint the Revolution anymore" [he laughs]. So, the revolution we make is against lies, it is for the truth.

Mexico, as I was telling you at the beginning, is full of lies told in schools, like the one that Antonio López de Santa Anna, who was born in Xalapa, sold Mexico to the United States. That is a lie [he laughs]. That is a lie; he was even the creator of the Mexican Republic. But we are confronting all these lies and many others through investigations that take a long time. We are fighting lies and making a gloss of values, for example: there is a woman named María Teresa de la Sota Riba, who fought for Mexico's independence and was condemned to be locked up in a convent. We have painted her, as a way of making known a heroine that almost nobody knew about, we could not find her in book research, strange, isn't it? [she laughs]. I have the pretension of having launched her [laughs] to historical stardom; me and another writer, who curiously has the same last name as me, Peredo, we both worked to make her known. That's how we are making our revolution, without weapons and for Mexico, for the truth.

In this way, we are not making abstract art, nor conceptual painting, nor are we following the ridiculous position of that great artist [he laughs] who sent a urinal, do you know the story, to make fun of the gringos, as we say here [he laughs], to make fun of them. From that, the gringos say: "Ah, well, it's a work of art". And excuse me when I say gringos, I don't mean it in a derogatory way, but critically, because green coat is the green jacket of the invaders who came here to Mexico at the time when they took away half of our territory, yes? They were the gringos, green coat [laughs]. That way, you have fun [laughs].

Once your weapon of resistance is the truth, what changes every time you finish a work?

What changes? Well, people begin, many people began to doubt, for example, that it was true that Antonio López de Santa Anna had sold Mexico to the United States. Because already in conferences, which I have even given in historical centers of the university, making that figure as it really is; because he did not sign the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, he did not sign it, it was another man. He also proclaimed the Mexican Republic, nothing more than that. And the people, when I ask them in the conferences: "And do you know that you live in the republic? Do you know who recast it?". There is silence, no! [he laughs]. "Well, it was Santa Anna" [I tell them]. I think it is changing a little bit because we are not only painting, but we are giving many lectures and I talk a lot.

And then people did not know who María Teresa de la Sota Riba was, and especially now the feminists are very happy because they now have their heroine, which they did not have before, and they are even painting her on the walls.

These are the things that are changing and, above all, I believe that the new painters are changing too. Recently, one of them, who was my assistant, said to me: "Master, may you give us the brush so that we can follow your path".. Well, yes, we are here slapping the idiocy of considering a pair of tennis shoes hanging on a clothesline as a work of art and things of that nature, which is the deviation. We are managing to attract a little, I think quite a lot, towards the culture of our origin, not only indigenous, but also of the revolutionaries, well, some socialists that, in a way, we are rescuing, right?

Do you believe that the emergence of this new race has represented a positive value in the construction of Mexican identity?

It's a good question you ask me, isn't it? It is as if you were asking me if the existence of God or the non-existence of God is worthwhile. These are things that happen in history, they are inevitable, one people always arrives and mixes with another. And so, fortunately, we no longer mix with the dinosaurs, right? Now we are other critters [he laughs]. Well, yes, it's worth it as soon as we make of the mixtures something positive. So, yes, it is worth understanding that we are a great universal community. It is not worth it when we deny, when we say that we are a mess because we are a jumble: the blacks, the whites, the greens [laughs]. So, it's not worth it anymore, great, because this kind of debate is now almost political, and no longer philosophical.

Bibliography

León-Portilla, Miguel (2005). “Presencia portuguesa en México colonial”, Estudios de Historia Novohispana, núm. 32, 2005, pp. 13-27.

Peredo, Melchor (2019). Los muros tienen la palabra. Xalapa: Universidad Veracruzana, 2019.

Charles Da Silva Rodrigues D. in Anthropological Philosophy, Universidade de Lisboa; PhD in Psychology from the Universidad de Extremadura with distinction. cum laude; D. in Intercultural Relations from the Universidade Aberta, with an outstanding mention. cum laude. He is a member of the snii, level i. Specialization in Neuropsychology by the Institute of Neuropsychology. criapLisbon, Lisbon. Master's Degree in Language Psychology and Speech Therapy from the Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (ual); Bachelor's degree in Clinical Psychology, ual. Degree in Philosophy, Universidade de Lisboa. Master's Degree, Universidade Guanajuato. Profile prodep. Collaborating researcher of the cemri–uab, Centro de Estudos das Migrações e das Relações Interculturais, Saúde, Cultura e Desenvolvimento, Universidade Aberta, Portugal. Member of the doctoral faculty of the University of Extremadura, Spain. PhD Candidate in History at the Universidade Aberta, Portugal.

Paula Alexandra Carvalho De Figueiredo D. in Intercultural Relations, Universidade Aberta de Lisboa, Portugal; M.A. in European Studies, Universidade Aberta, Portugal; B.A. in Philosophy, Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Letras, Portugal. Collaborating researcher at cemri–uab from Universidade Aberta, Portugal. Candidate member snii.

Melchor Peredo y García was born in Mexico City in 1927. He is recognized as the last representative of Mexican muralism among scholars. His vast work, developed over more than seven decades, can be found in several emblematic buildings in Mexico, France and the United States. For the last four decades he has lived in Xalapa, where most of his mural work is concentrated in the municipal palace, the Superior Court of Justice and spaces of the Universidad Veracruzana. He mainly uses the fresco technique and developed an innovative method of applying murals on cement sheets. He has reconciled his artistic work with university teaching, transmitting his knowledge to new generations. He is the author of Xalapa, stronghold of the Mexican muralist revolution (2015) y Los muros tienen la palabra (2019).