The sonic border of the wixaritari ceremonial experts. Liminality for the control and protection of the rains.

- Xilonen María del Carmen Luna Ruiz

- ― see biodata

The sonic border of the wixaritari ceremonial experts. Liminality for the control and protection of the rains.

Receipt: May 31, 2023

Acceptance: October 13, 2023

Abstract

The sonic border is a sensitive state. It is the perception of a corporeal presence of sonorities that circulate in space-time: actions, emotions and behaviors. Ceremonial experts wixaritari of Tierra Azul identify with the word 'enierikavisio-auditions or audito-visions (nierika) in liminal divine auditory interstice, in demand of the analogies of ancestral history and ritual practice. The rebirth of life is to take hold of the control and permanence of the rains, to consummate the cycles of darkness-light. Through cosmopolitics, the divine sonic iconicity intervenes in agrarian territorial limits, the defense of the cosmogonic territory and in controlling ancestral disagreements.

Keywords: 'enierika, anthropology of the senses, cosmopolitics, sonic frontier, liminality, nierika, wixárika

the sound frontier of wixaritari ritual experts: liminality, rain control, and protection from rain

The sound frontier is a state of the senses. It is the ability to perceive a physical presence of sounds circulating in space and time: actions, emotions, and behaviors. In pursuit of analogies of ancestral history and ceremonial practice, Wixaritari ritual experts from Tierra Azul use the word 'enierika to refer to vision-acoustics and nierika to speak of acoustic-visions at the liminal, divine interstices of hearing. The rebirth of life is about gaining agency to set and control the duration of rainfall, and master the cycles of darkness-light. As a result of cosmopolitics, the divine iconicity of sound figures into rural land borders, the defense of cosmogonic territory, and the handling of ancestral disagreements.

Keywords: anthropology of the senses, sound frontier, nierika, 'enierika, wixarika, cosmopolitics, liminality.

Sonic Frontier

In 2011 I was shocked to hear on the internet the claim of the traditional authorities wixaritari because of the possible modification of the ancestral territories where the divinities live. Following government concessions for mining projects in Wirikuta, during a ceremony at the sacred site of Paritekɨa, on top of Cerro Quemado, in the sacred place of Wirikuta in San Luis Potosi, the deities were heard in the voice of the blue deer, Tamatsi (Our Elder Brother) Kauyumarie, who announces the danger of not being reborn and flourishing in the world. The ceremonial guides (mara'akate) of an entire region unified a single voice of help from their eldest ancestor -accepting the help of civil society and some governmental sectors-. The transmission of that divinized listening was to the wixaritariI asked myself about the native conception of listening to the national society and through digital and conventional media as a response to that threat. I asked myself about the native conception of listening of the wixaritari to identify the auditory perspective of their action and the discourse of sonorities among their ceremonial experts.

Based on the very categories of Wixarika thought and their semantics, questions should be asked not about vision or visions, but about the auditory implications of jicareros and peyoteros of conical ceremonial centers (tukipa)the elders of the parental adoratories (xirikite), the senior advisors (kawiterutsixi), healers and mara'akate. Based on the category of nierika (vision) that is constantly linked to their visual perception, I set out to think in terms of hearing references to visionary abilities and found in vocabularies, dictionaries, anthropological and narrative literature the word 'enierika and its variations.

I arrived at the metatheory about this perception through field practice with ritual specialists. wixaritari.1 I found a statement about the word 'enierika, translated as the verb "to listen" or the noun "listen". They experience experiences in which they communicate with, are listened to or fail to listen to their divinities of origin stories and direct ancestors identified as "people": grandparents, great-grandparents, deer-men/women, wolves, wild boars and other animals and insects. When comparing with my listening, I found a text with the following explanation: "a perspectival discourse as those differences and similarities between some existents and myself, by inferring analogies and contrasts between the appearance, behavior and properties that I ascribe to myself and those that I ascribe to them" (Descola, 2012: 177).

In the ceremonial acoustic space, the auditory reception or dialogue with ancestors wixaritari Situates sounds that communicate in circumstances of unspecified proximity. Identification of timbres and sound qualities is essential. 'Enierika and the way it is semanticized: to understand/perceive/agree/obey, in some circumstances it is a device or an auditory spark that activates a ceremonial expert vision (nierika); in another, it is the expert hearing ability in which hearing alone predominates (nierika) (see Luna, 2023: 92)..

For its part, the category of nierika (vision) or "gift of seeing2 nourishes the anthropological discipline on the visionary complexity of the Wixarika culture (cfr.. Lumholtz, 1986; Zingg, 2012 [1982] [1938]; Furst and Nahmad, 1972; Fikes, 1985; Neurath, 2000; Schaefer, 2002; Chamorro, 2007; Neurath, 2013; Kindl, 2013, among other authors). It is a systemic category in relation to exchanges, gifts, loans, actions, objects, narratives, and ceremonial obligations.

This article proposes the term "sonic border", which converges from the study of the anthropology of sounds and the anthropology of the border, which is lived from intra and inter: cultural, pan-cultural, community, border, cosmological, state, national, continental relations. Miguel Olmos urges us to pay attention to an anthropology of the border as a complexity still in process, in those elements of culture that have remained hidden in social logics and with other clothing (Olmos, 2007: 33).

The sonic boundary is a state sensitive. A corporeal presence of sonorities that circulate in space-time, actions, sensorialities, emotions, politics and behaviors. Ceremonial experts wixaritari identify with the word 'enierika, visio-auditions or audito-visions in liminal divine auditory interstice, in demand of the analogies of ancestral history and ritual practice; however, it is not exclusive to vision and audition, as the senses change order.

It is a presence in undefined locative spaces, an unfolding of sounds in an imprecise line of auditory space and a "cotemporality" (Fabian, 2019). Generally under the influence of the ingestion of hikuri (peyote), perceptual states require the interaction of a variety of factors.

In the auditory plot of the search for the life of ceremonial experts. wixaritari of northern Jalisco, it is common for unconventional sounds of the language itself to dialogue as a form of ancestral speech that is sustained by the founding stories wixaritari and its ceremonial practices. Granted by the ritual auditory experience 'enierikaThe aim is to reach the "language of rain": water, wind, whirlwind, rain, thunder, hurricanes, heartbeats, animal noises, insects, strings of musical instruments, drums, bull horns, fire, drinks and others... They promote collective actions that aspire to satisfy the situations related to the life of the people and the environment. wixaritariThe rituals are not always successful: the function of the ritual is underlain by unresolved conflict (Geist, 2006: 174). However, good results will not always be obtained: the function of the ritual is underlain by unresolved conflict (Geist, 2006: 174).

These sounds that speak or that establish connections involve reflexivity and metalinguistics, as the wixaritari employ a formal language to talk about this type of speech through sounds. During the auditory practices of the families of the ceremonial offices called jicareros of the Tuapurie ceremonial centers, they hear the howl in two forms: as "wolf people", "wolf people", "wolf people", "wolf people", and "wolf people".3 howling and like wolf-people who honk bull horns (' )awá) of the pilgrims during their journey to the sacred sites on Cerro Quemado (Wirikuta) (interview with Bautista de Tuapurie. Tierra Azul, December, 2016). At the peyote festival4 in Tierra Azul, Kɨmɨkime "wolf people" is the second primordial hunter ancestor.5 and goes to the left yu'utata "the north", is 'Ututawi',6 is 'Arikate (mayor) (see Luna, 2023). The "beeping" of the bull horn as a sonorous icon is the howling "voice" of the wolf-people that links the community to the Wirikuta desert AND is also a metalinguistic index (something that points to such a code).

In this audition, the sound of physicality is absent, since neither the "wolf people" in physical form, nor the peyoteros with their horn aerophones are present at the moment. Nevertheless, the receiver knows that it is the historical ancestors and the peyoteros, who carry and blow the bull horn that are in Wirikuta or are returning to the community. In the beeping of the bull horn, the mimesis of wolf people provides a certainty, a "positive" sonic boundary that communicates the advancement of the pilgrimage in the ritual state in which the ancestral hunters of the hikuri. It is contrary to a game of imitation of animal sounds to achieve auditory confusion between victim and predator, as Mattias Lewy shows us in the case of the Pemon (Lewy, 2015). An [absent] mimicry as "a way of getting into the skin of the character one mimics, of taking his mask" (Vernant, 2001: 76). A similarity with the Amazon in Peru when the sound provides, to the auditors of the ritual, a sensitive reception of the auditory face of the invisible (Gutiérrez Choquevilca, 2016: 20).

Ceremonial listening practice requires sacrifices, ceremonial commitments and obligations, knowledge of ancestral histories, and attendance at sacred places and sites/places, shrines or ceremonial centers, and is also lived in urban communities. wixaritari of recent creation. It requires being attached to the ceremonial organization according to the dynamics of their particular and collective way of living the Wixarika life.

In the case of companies that do not wixaritariThese forms of "rain speech" are not taken into account in land management decisions. Liminal situations arise if the auditing societies do not listen equally to each other. Then, the sonic entities that are listened to by ceremonial experts are not taken into account in land management decisions. wixaritari cannot do their job in accordance with the origin in which they were created. If cosmopolitics refers to a way of looking at and approaching something, a way of thinking (Stengers, 1997, cit. in Martínez and Neurath, 2021) from that conflict or "disagreements between worlds" (see De la Cadena, 2010) is that a problem of the sonic border emerges.

By situating liminality, ritual sound reveals tensions and conflicts due to the instability of the "politics of ritual" (Mier, 1996). Then, it is viable to create links through exchange, to make visible [audible] the latitudes and the edges of the limits, the fragility of the links, the margins of the stability of the relationships that cross, disturb and reconstruct (Mier, 1996: 95-98) the renewal of Wixarika life. Thanks to their political skills (De la Cadena, 2010), ceremonial experts bet on resolving situations in the pursuit of life.

When the inherited territory is conceived differently, negotiations must be undertaken so that the sonic boundary is activated and that liminal stage operates in favor of the wixaritari. It is the foundation of another reality, a reality, understood not as a set of factual events, but as a normative space (Mukarovsky, 1977, cit. in Mier, 1996: 109).

The presence of a Wixarika entity that is not seen, but speaks differently, is fundamental for the continuity of temporality. tikari (when it is darkness). The instability of the continuity of Wixarika life favors the intervention of experts who listen to the divinized hills. They are the natural places where the winds that carry the rainfall to the lands of the farmers of San Sebastian Teponahuastlan or Wautia. It is urgent to control rainfall in the rainy season so that the sowers can successfully complete the agricultural cycle, since the birth of the children-roots that have been inherited by their ancestry is endangered. Consequently, it is to achieve the transition from a wet season to a dry season and a new cycle for the renewal of life.

These are the hills that guide the flow of rainfall and are inhabited by ancestral entities. Sometimes, the ceremonial offices are in constant debt with those divinities, so they are subject to the payment of mandas from the jicareros and to the negotiation of the mara'akate with the divinities; thus, the hills fulfill their role and the rains arrive in time and form to the polyculture slopes. In the hill Kwate Kaxiwaritsie ("where it eats storms") dwells the divinity Takutsi, who "speaks differently" (a natural guardian) and does not belong to the Wixarika agrarian territory, but it is their cosmogonic territory. A "muffled hill" due to the ceremonial debts of the same people. wixaritari. In August 2022, jicareros from the eight ceremonial centers of Wautia were alerted that a 5G telephone antenna would be installed on this hill that belongs to the municipality of Totatiche. They spoke with the municipal authorities to explain the importance of their deified hill, most urgently, to "activate" the sacred site of the hill for the emergency rains to get generous harvests in the land. wixaritari by the third week of October 2022. The Waut community membersia, the municipality and the owner of the property signed an agreement. Thus, the mara'akame He chanted (dialogued and negotiated with the divinity) and the divinity pointed out the place where the sacred place would be relocated on the same hill. Thus, about 80 jicareros circulated and paid the outstanding "debts" (interview with Martín Vázquez, president of the jicareros of the ceremonial centers of Wautia, 2022).

In this testimony the Wixarika claim to hereditary territory is the statement of the listening 'enierikaas an ancestral speech level. As important as an antenna teiwari (foreign) 5G that facilitates communication. A way to readjust the internal competences of the traditional authorities vis-à-vis the municipal and private authorities and internally with their communal authority.

Listening "from here to there" and listening "from there to here".

Derived from the perceptual triggers of the nierika (see) and 'enierika (listen) the exegetical explanation of the exchange of eavesdropping between deities and ritual specialists can be deduced. wixaritari who have acquired listening skills. The cross-listening is elicited by the demonstrative adverbs listen "from here to there" and listen "from there to here", with their different variations. They are "language games" that refer to "the whole formed by language and the actions with which it is interwoven" (Wittgenstein, 2017: 37). It is a reference, deixisThe use of sound, signaling or directionality of a linguistic ideology to explain what happens in a certain auditory time-space and also as performative practices performed by ceremonial experts in the intermediation with their divinities and through sonorous or light objects.

This sonic transition is a discontinuous temporality, it is "a before" and "an after" to reach the analogisms of the stories of origin that resolve the drama of the dawn, of the birth of life or, well, situations that affect them in their particular ceremonial, family and community life. The native category nierika is nourished by the auditory perceptual resource of 'enierika and sounds are placed on the face hixie (in front). The jicarero Marcelino González of Tierra Azul names locative expressions to exemplify this type of situated listening, which involves communication between the wixaritari and the deities as follows: listen "back and forth" (manemutane) "upstream but not downstream" and hear "from there to here" (manemuyene7) "downstream, not so steep" (translation Xitakame Ramírez).8 Paula Gómez (2008) clarifies that the prefix ye- has as its directional meaning "outward", "downstream" and as its static or locative meaning "inclusion". Thus, in manemutane the trajectory of the movement is "inward" (Gómez, 2008: 34). As indicated and translated by Dr. Xitakame and, for his part, by Gómez, the prefix ta- can express, among other directional contents, the trajectory of movement "towards the interior" of an enclosed space or as locative "entrance", or "edge" of an object (Gómez, 2008: 34). It is also the affix 'ana (here) or another spatialization indicator comparable to the following: manemutane. It is a way of situating listening.

The songs of the niawari express the thought (Luna, 2005: 11), the teacher Gabriel Pacheco classifies them as Tayeiyari niawarikayari (Pacheco, 1995: 88) and are played with musical instruments of xaweri and kanari. The oral narrative makes locative references to an undefined place that indicate auditory triggers that will facilitate the vision such as "where", "there", "there, "there", or the trajectory of the movement: "they are coming down", "there I was coming", "there behind", "where the flower is danced", "they are coming down with those messages".

The descending melodic play of the chants of niawari refer to a listening "from there to here", the result of their personal and liminal experiences, sung in first and third person and are performed to sesquiáltera rhythm and are dance-like zapateados (see Luna, 2004; 2005: 15, in Luna, 2023). To the musicians who listen to the wind, the intonation of melodies is communicated (De la Mora, 2018: 144). The emphasis of the chants is on the locative experience of an imprecise space, on a sonic border where the visionary experience is obtained.

For their part, ceremonial experts mara'akate project a face to the east-Wirikuta. As receivers, they affirm that it is heard through the right ear, below (the south, but also below is the west and the north), there are the non-humans. Thus the deixis of the face connects with the geographical cosmology of the Wixarika territory (kiekari).9 This reflects an asymmetrical conception that relates to the movements of the solar cycles beginning with the winter solstice, the birth of the child Sun. The heuristic proposal is that the sound moves as a terrestrial (auditory) orbit, as if the five sacred places formed a face in which the sound moves as the ancestral story of the deluge is narrated, which is born by the south-north displacement. It is an auditory story of life-death-life. It begins on the right and ends on the right, to the south. The ritual specialists carry on their face the five sacred places, their face-head is at the same time the earth's orbit (Luna, 2023).

From the deployment of sounds in the sonic frontier and from the locative references to an undefined place, the sonic conceptions of the divinities and the ways of conceiving their territory and communal limits emerge.

The hereditary territory. An auditory ritual path

The cosmogonic territory of the wixaritari I know governed by the yeiyari (the ceremonial path -the ceremonial obligations-). On the other hand, the temporalities of light and darkness reveal the asymmetries of the Wixarika culture in order to achieve the renewal of life.

In temporality tukariIn the daytime, the deer ancestor Tamatsi ("Our Big Brother" and its various forms of naming) predominates. If the temporality of darkness prevails, tɨkariThe divinities "Our Mother Earth", "Our Mother Corn" and more aquatic and rain divinities, sonorously express their spaces of power to make life sprout from the sowing of the primordial polycultures. For example, Takutsi, the grandmother, speaks through the cane, a sonorous object with agentivity and visionary capacity that announces creation or destruction (see Luna, 2023).

Families of the parental adoratories10 from the various agencies of Tierra Azul participate in ceremonial positions in the tukipa Tierra Azul, they may belong to the Wautia and Tuapurie. They listen to the ancestry by double community, for what they establish familiar, ceremonial and communal relations attending to the intermediation of ceremonial guides and elders that are governed by different divinities. They are represented by a communal hierarchy: Traditional Government, kawiterutsixi (councils of elders), xukuri'ikate (jicareros), hikuritamete (peyoteros) and mara'akate (ceremonial guides) and the Commissariat of Communal Assets. They intervene in the communal life, the yeiyari and the defense of territoriality.

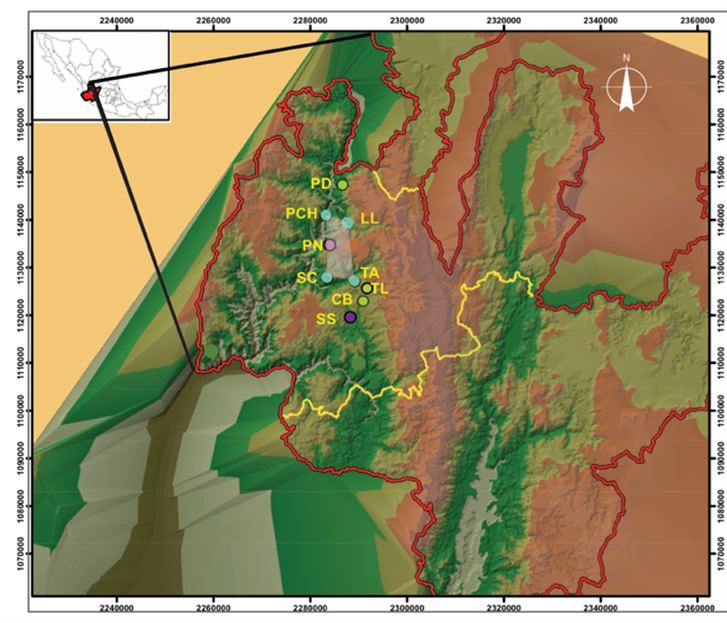

Territoriality wixarika with its ancestral dimensions has been approached by intellectuals and lawyers wixaritari. They have been joined by different anthropologists (Medina, 2003 and 2020; Téllez, 2011; Liffman, 2012), who report and recontextualize from their own research approach on the history, the territory inherited by ancestry, displacements and the reasons for the claims. The cosmological territory in the Sierra Madre Occidental is defined by the four rumbos and the axis mundi in the middle and is summarized in the graphic figure of the quincunx which covers 5,000 square kilometers and is sized to the large temples (tukite) and hundreds of rancherías, where the parental shrines are located. xirikite (Liffman, 2005: 54-57).

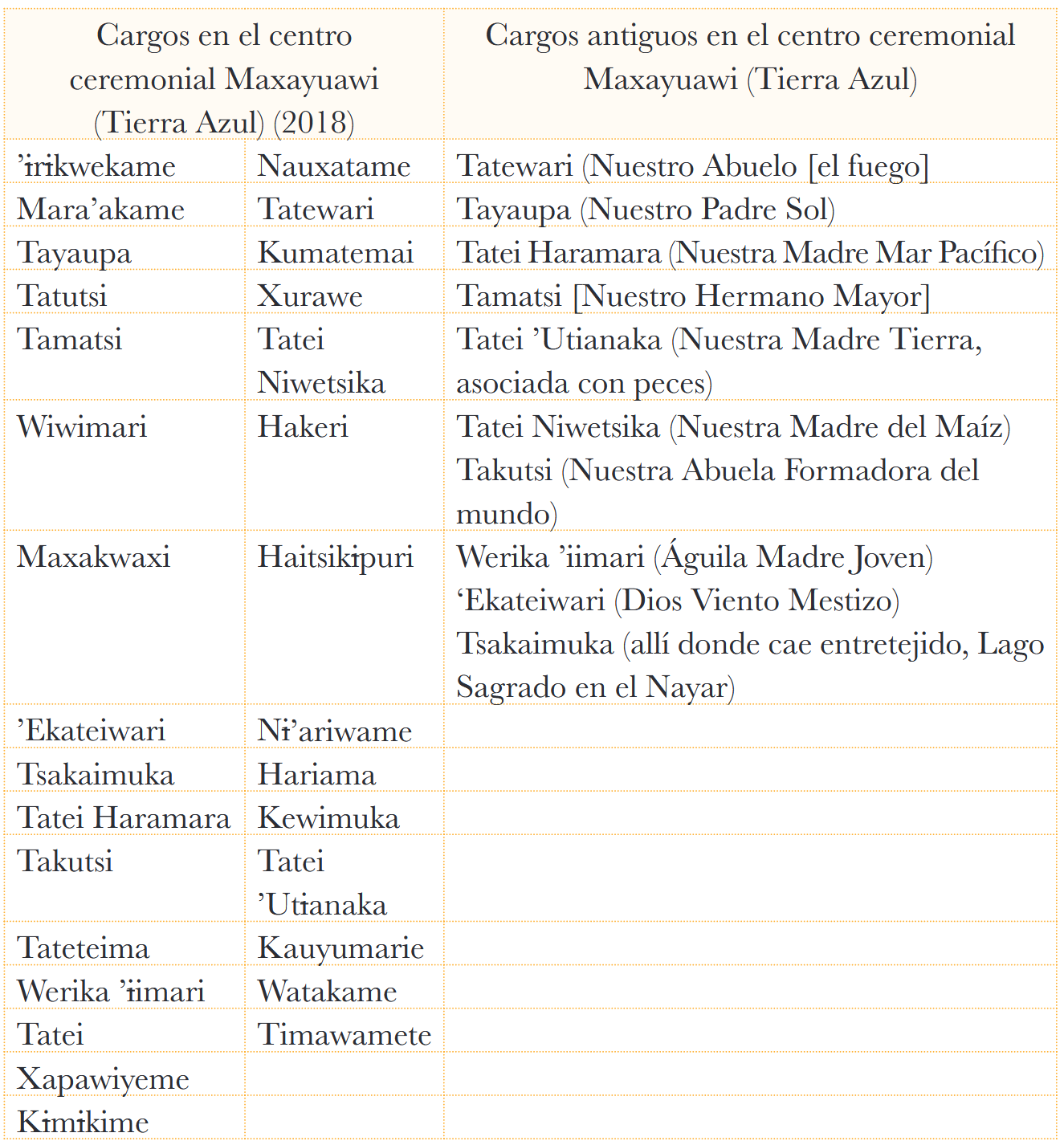

Los wixaritari took the names of deities or topographic places or divine actions from their ancestral stories to name their ceremonial centers. The ceremonial center of Tierra Azul is called in Wixarika Maxayuawi ("Blue Deer"), recognized by the community of Wautia as part of their ceremonial centers. It is the oldest denomination: yuawi (blue) has an indexical relationship with everything that has to do with rain, water, deer, a woman's name, blue corn-person, wolf, sky, puddle, sacred place, ceremonial center, etc. It is also Muyeyuawi ("it stops the blue" or, in a metaphorical description, "where the blue sky is placed"). To the south, in the vicinity of a large rock near Tierra Azul, there is a spring or waterhole called Muyeyuawi, where holy water is collected.

Maxayuawi is associated with Wirikuta and with rain deities, peyote spot, black deer, young corn, blood of the blue deer, vital energy, ancestor of the non-Indians, ancestor of the deer, Kauyumarie in his nocturnal quest (vine. Negrín, 1986, in Aceves, 2009; Lemaistre, 1997; Zingg, 1982; Negrín, 1977; Fikes, 1985; Medina, 2014).

Different traces of the presence of Maxayuawi as an indexical sign converge in the Wixarika hereditary territory as the life of all the ancestral deities. The ceremonial office of the tukipa called Wiwimari (Moon, 2023) is a "big" deer and a snake. Wiwimari unites the hunters who go to the mountains to hunt the deer and helps to find them. In Hikuri Neixa he carries deer heads in his hands and is fundamental in the dance movements performed by the peyoteros.

At tuki of Tierra Azul, in 1995, the mara'akame Alfonso González, cantador for five years, tells the ancestral story of the founding of the community of Santa Catarina and its ceremonial centers, such as the tukipa Maxayuawi (Blue Earth). Recall that this tukipa is part of the agrarian territory of the Waut community.ia:

[...] after they began to walk with the eagle for a few days, a large boulder came across them again [...] they asked the star to knock down the boulder that prevented them from continuing to walk eastward [...] they called this boulder Kairiyapa,11 today is Santa Catarina in Spanish: "por donde inició brota una especie de humo". Thus, they decide that they have found [...] where they will live and where the ceremonial centers of Santa Catarina are located today [Kairiyapa]; Tierra Azul [Maxakayuawi12Tutsita?, Pochotita [Xawepa] and Las Latas [Matsit].ita]. Since that appearance, the charges have been going on so that the world continues to survive (Field work, October 11, 1995, in Tukipa Tierra Azul. Recorded interview with mara'akame Alfonso González, simultaneous translation from Wixarika by Juventino Carrillo and Martín Carrillo).

The persistence of such foundational stories is found in the accounts of the inhabitants of the Tierra Azul ranches, who trace the origins of their jícaras to13 family members in Santa Catarina.14 These jícaras fulfill a double role: they remind and keep in force the mutual ritual commitments, which are renewed every five years between the Maxayuawi ceremonial centers of Wautia and Kairiyapa, of Santa Catarina. At the same time, there are migrations of families between both territories, which causes a human displacement that momentarily erases the common border, justified by the designation of deified jícaras, which are assigned by the elders. The constant migration of people between these populations is reinforced both by the new kinship ties that come to be produced, as well as by the seniority that is recognized to some inhabitant, who without being born in the place decides to settle in the community.

In the assemblies held in the communal agencies, the local authorities insist on the obligations of the community members. It is common to hear in the Tierra Azul police station and through the loudspeaker information about the demands made on the jicareros, it is the agent of the commissariat who complains to the community members about the lack of assistance in the defense of the territory and threatens to charge them for their faults and exhorts them to comply. The community members maxayuawitari listen to the future actions to be carried out in relation, for example, to the still unresolved territorial problem of the territorial limits with their mestizo neighbors of Huajimic. They are audible glimpses of the threat of losing the territories where the divinities live: Our Mother Earth, the Deer and their divine variations.

Tamatsi "Our big brother" and its various forms of naming. An auditory territoriality

The deified deer in the Wixarika territory can be thought of as a totality and variability of Wixarika ceremonial life. In Roy Wagner's terms, in a fractal motif, a totality that relates, becomes and reproduces the whole, but are not a sum of something individual (Wagner, 2013: 91). In the exegesis of the Waut jicareros.it is clear that the tukipa is the cosmos:

The singers say that it is a world, when it was created, first the grandfather fire was born; then the father sun came out, but it was hot and everyone was dying. Then the kakaiyarixi They planned and climbed up to Father Sun with a ladder, but it was not a ladder, it was a candle and they stopped them where the sun is. There was a house, a kalihuey. Inside that circular house, on the right side [tserietaThere is a stick that is a hauri (candle); on the left side ['utata], there is another stick, which is a world; the jicareros stop the world by performing ceremonies and delivering offerings (Fieldwork, interview by Tatutsi, Tierra Azul, 2018).

As a fractal motif, the ceremonial territoriality has the shape of a deer, its contour are geographical points to scale from the celestial vault and projected on the buildings of the conical ceremonial centers. The jicareros of Tierra Azul draw in their minds that body of the territorialized deer and begin with the head of the deer itself. That is to say, the tukipa are points that, as a whole, trace and unite the body of the major ancestor. It expresses a macrocosm: the cosmogonic territory, and a microcosm: the body. For them, the ceremonial center is alive, it behaves like a person who acts according to emotional states, such as the sense of revenge or appropriation.

Maxayuawi (Tierra Azul) is the beginning and head of the deer's body, the "up" part, the ancestral and spatial region of Wirikuta. The location of the other parts of the deer's body is conformed by the numerous tukipa located in the region wixarika. Other points are the tukipa Matsitaita (inside Big Brother Deer) [Keuruwitia in the literature] in Las Latas and Kairiyapa in the Tuapurie community (interview with jicareros Marcelino and Alberto, April 2018); but the jicareros are not clear on how the other parts of the deer are assembled.

In a heuristic elucidation, the indexical iconicity of the ancestral deer is linked to an acoustic spatiality by means of ritual deposits such as arrows. 'iriyou, feathers muwieri and a variety of objects nierikate that possess "ears" (Luna, 2023), dancers, movements, food and others. In the auditory interstice, the ceremonial listeners perceive those sound objects as acoustic holograms that constitute them and are constructed from their experiences and ancestral stories. Wiwimari in the peyote dance is the deer who goes to the center of the quincunx of the hait dancers.iriwemete "Those who know how to make clouds" and expresses its sonority through clashing sounds such as seeds, deer hooves, plastic, metal tabs of soft drinks, reeds and other materials, arranged in belts, in ceremonial hats, in the cheeks of the peyoteros (peyoteros, or peyoteros), in the karkajes (Moon, 2023).

Through temple ceremonies, parental worship, and during ancestral storytelling, the wixaritari listen to the deer in different forms of speech; for example, the women talk to them while processing and preparing tejuino through the sounds of boiling fermented maize; Matsi Kaiwa15 ("Big brother downstairs") is associated with the kieri and is heard through the sound of the small violin called the xaweriTamatsi Kauyumarie (Our Big Brother Blue Deer, the first singer) sing in Wirikuta by the small violin xaweri and through the intermediation of the goldfinch (kuka'imari); likewise, the black bird (tukari wiki: daytime bird) sing by the jaranita kanari and by the intermediation of the "mountain bluebird" [magpie]; Maxakwuaxi (the White-tailed Deer) sings by the sound of the drum (tepu); Yumu'utame (Their Heads-people), major ancestor of the parental worshippers, speaks through the howl of the ancestral wolf; irikate (arrow person) speaks like the wind; Maxayuawita (place of the blue deer) is the beating of the heart; Tatei Ut (place of the blue deer) is the beating of the heart; Tatei Ut (place of the blue deer) is the beating of the heart.ianaka (the fish-goddess, Rain Goddess of the East) and Mekima or Tatei Maxame (the mother of women living in Yukawita) are heard speaking as the sea of the Tatei Haramara (Our Mother of the Sea); 'awatamete (horn-people) are heard through speaking noises and by the attributes of primordial hunting animals.

These denominations and their varied ways of naming the deer express variations of a totality, whose elements cannot be added or ordered, because "they do not constitute a sum that implies a totality. If a totality is subdivided it fragments into holographies of itself, but they cannot be ordered" (Wagner, 2013: 91). So they can be considered as fractal motifs "that remain between the whole and the part, so that each of them include the total relation" (Wagner, 2013: 94).

Corporeality is the place of the action of affection, impulse and creation, the place of disturbance for acting (Mier, 2009: 16). The liminal experience of the dance of the Ni'ariwamete is one of an unresolved conflict between the ancestral and rain divinities, in front of a fire from an incandescent trunk, life or death is at stake. It is necessary to overcome an ancestral drama in the search for the control of the rains and the rebirth of the seeds of the rainy season sowing. It is a sonic frontier. The following is a perceptual narration.

Dance of the Ni'ariwamete of the Namawita Neixa ceremony. The disagreement between the night sky and the ancestors.

If the interior of the tuki or conical temple is the cosmos, in its interior reigns the temporality of the rains. Inhabits the divinity of the stories of origin, is Takutsi Nakawe, protagonist of the ceremony Namawita Neixa in the ceremonial center Tierra Azul.

The dancers called Ni'ariwamete perform a rite with a burned ocote tree ('utsi) of five to six meters inside the circular temple, are the guardians or protectors of the deity Takutsi Nakawe. During my ethnography (2018) I have recorded that the dancers circle around the fire with the guidance of the drum (Our Grandfather White-tailed Deer) in circular, levorotatory and zigzagging directions.

Hearing an auditory symbol implies "a convention" (Kohn, 2013), the sounds of the drum tepu will be heard at parties associated with rainy weather. If the listener is outside the tuki (conical temple), the sound of the pulse of the drum that is emitted from the inside out creates an enveloping effect through the canyon vault, like a modulated repetition or delay (delay) of the sound signal. The sounds dominate the acoustic space and guide other senses to overcome a liminal state, since the permanence of the rains is in danger and at the same time a divinity must be controlled. The goal is to dilute a dangerous border with an incandescent trunk that must be extinguished. A sonic border emerges as the audible manifestation of the divinity Takutsi Nakawe. The sound of rain dancers predominates over a hazy light of fire from a log and candles and caused by smoke from the fire.

In the dance of the Ni'ariwamete, in the ceremony "Namawita Neixa", the rain deities and the ancestors do not reach agreements, a dark time prevails, the ancestors do not understand the chant of the creator deity. The deity is the night sky and does not want to cross to the side where the ancestors are. A series of elements such as the huaraches of the Takutsi divinity are the sign of the night, the deity reconstructs itself; that is, even if they try to take it with them, the night sky will invariably renew itself as it does every night.

The dancers insistently step on and extinguish the fire until it is completely extinguished; they are responsible for keeping Takutsi safe and safeguarding a process of darkness. They complete the process of perception by giving continuity through this ceremony to a dark time. A struggle is observed between solar deities and female deities of darkness at the advent of the dark time. The solar deities cannot control the deities of the rains, it can only be achieved by the negotiating resource on the part of the mara'akame. It also fits the practice of the sower: it is the process of slashing, slashing and burning, finally the deities of the rains manage to extinguish the fires.

The dance of the Ni'ariwamete in the ceremony "Namawita Neixa" (which translates as: nama "cover", "cover", "cover". witari "in the waters" or 'itari, "manta del venado", neixa "dance", translates as "Dance to cover the waters"). It is a festival for female deities such as Tatei Niwetsika (Our Mother Corn) and Takutsi Nakawe (Great Grandmother Growth). It welcomes the rains and helps to control them. Namawita Neixa marks the beginning of the rainy season, a dark time. This feast in Tierra Azul is preceded by the ceremony called Karuwanime Xeirixa, dedicated to Father Sol.

The dancers called Ni'ariwamete are the guardians or protectors of the Takutsi deity Nakawe, they and the jicareros meet inside the tuki, have turned the equipales facing west and to the back of the fire. In this feast a woman of corn will be made, 'iku (Tatei Niwetsika), tie the plants and dress her in her five skirts and blouses, xikuri (scarf), chaquira medals, feathers. In front of the fire are the main 'irikuekame, Nauxatame, second of the mara'akameMara'akame, Tatutsi and Tatewari; all the jicarero men on the north side of the tuki and, bordering the wall, all their wives, jicarera women carrying candles to the south side; in turn, the placement coincides with the arrangement of the ceremonial courtyard's deities' shrines.

At 10:30 p.m., the singing and drumming begins. tepu is placed next to the singers and in front of the ceremonial oven or "the place of the women". The mara'akame Juan Hernández welcomes the deities by beating the drum. Then comes an hour of singing. The feast chanter Namawita Neixa represents Takutsi Nakawe, the chanter of the Hewixi [ancestors] (Neurath, 2002: 272).

The Ni'ariwamete are dressed with various muwierite (feather bouquets) placed on the head and belonging to the different jicareros; in the right hand they carry a rattle (kaytsa) and on the left, a muwieri. There are five dancers and they are identified as topiles or "chalanes" of the jicareros.

As they dance, they form rows in serpentine movements, first in a levorotatory direction around the fire and then zigzagging across the width of the circular temple and among the other jicareros who are in opposing rows. They circle for about half an hour and prepare themselves because the rite will begin with an ocote on fire. ('utsi) of five to six meters; the jicareros go to load and tie the ocote.

They turn around in a clockwise direction and immediately Tatei Niwetsika, who at that moment is a baby, appears, carrying the jicarera of the deity 'Ut' on his back.ianaka (Goddess of the Rain of the East and Goddess of Peyote). In front of this woman will be the ocote on fire. At the front of the line they are led by the Xukuri X cargo.iriwaame (Jícara-Esophagus) and the second Mara'akame.

Behind Tatei Niwetsika is an old woman, Takutsi Nakawe with her cane and her mask, wearing her huaraches of taki, the plant with which the hats are made, with three holes, black skirt and a wooden mask, "before I wore hair, now they don't take good care of that, before it was cooler, now it's just the mask" (interview with exjicarero Antonio Hernández, 2018).

The exegesis of the villagers narrates that Takutsi Nakawe carries a child not their own, who are perhaps the same wixaritariThey are wearing a wooden mask with an "old" face. In front of them are tied ocote sticks that are a big torch, they go around five times in a clockwise direction and then they stand in front of the women on the far right side of the tukiAs they pass by, the women pour "holy" water that was collected from the springs and pray to them. It is important to note that all the "jicareros" of the feast are fasting. Not fasting is dangerous for the Ni'ariwamete, since they could have some tragedy at the time of burning the stick with their stomping or jumping. Gutiérrez notes that, at the summer solstice, at the beginning of the rains, the sun begins its return from north to south. The counterclockwise (levogyrous) is associated with fertility and solar emergence. The dextrogiro schedule represents the garrisons of nocturnal, perverse and unbridled beings (Gutiérrez, 2008: 300-301). In the tuki of Wautito lightning illuminate the roof of the tuki at noon without being able to enter through the north-facing window (Gutiérrez, 2008: 304).

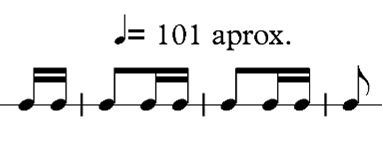

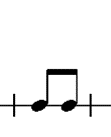

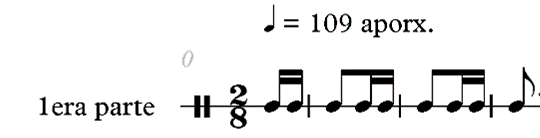

The temperature is extreme because of the huge ocote lit inside this space, the ventilation does not circulate at all, it is difficult to breathe. The door of the tuki of the ceremonial center Tierra Azul is closed with blankets, there are so many people inside that it is difficult to pass, each jicarera and jicarero have taken their place. Inside the ceremonial center the attention is focused on the sound of drumming and stomping. You can hear a ostinato in 2/8, built along the first part of the time signature, based on two rhythmic motives. Motive A or 1 is made up of an eighth note on the strong beat and two sixteenth notes on the weak beat.

Occasionally the motif B or 2 appears, which is formed from two eighth notes that makes it easier for the dancers to dance Ni'ariwamete.

Every five laps the dancers make reverse movements and shout "wolf", "Indians", "jújújújújújújújujujuuuu"; from minute 5:05 (the second part) the ostinato transition in the tempo The dynamics in this second part increase in relation to the first part, when the execution is stronger.16

In the background you can hear the song of the mara'akame and their seconds. The rattles (kaytsa)17 The dancers' movements and their shouts release tension. At one point, women and men laugh at a person who wanted to help a male dancer dance.i'ariwame that he was exhausted, but he makes a mistake and dances with his shoes on backwards.

Everyone waits for the moment of climax when the dancers trample on the burning trunk, it is an event that generates great tension, because not only they, but the whole community is in danger. tuki. If something were to happen to the Ni'ariwamete would be because someone transgressed the norms, did not fast and did not perform his personal sacrifices as the person in charge of his jícara. That nothing happens is determinant for the party to conclude in a favorable way. Before the rite of extinguishing the fire, the Ni'ariwamete were worried and at the same time comforted that this was their last year of sacrifice. The moment of tension arrives with an intense zapateo that gives the accelerated pulsation on the fire that covers in its sonority the circular temple, it also increases the rhythm of the tepu. This is a liminal state, there is danger, it is a sonic frontier.

Audio 1. Sound example. In the dance the Ni'ariwamete extinguish the ocote that they set on fire. Ceremonial center Tierra Azul, Jalisco. Recording: Luna, 2017.

Trampling the fire in an unrestrained way is like feeding the sonority of the acoustic space and resolving a situation in danger (listen to sonorous example 1). Each dancer tries to extinguish the fire with his jumping, the fire is extinguished little by little. It is a moment of deep stress and the emotions reveal the confabulation of the restrained breaths of the audience that observes, the murmurs and expressions that arise from an exalted moment that reveals the ambivalence of the dancers of the rain: vulnerable and strong, and finally the comments of relief on the part of the charges before the flame that fades before their eyes. As the ocote fades away, the rhythmic beat of the tixeukua wixarika With relief he exclaims: "I'm going to drum! I'm going to drum...!". There is no lack of those who help with the tepu to continue the party.

After extinguishing the fire their "helpers" relieve them; they can be jicareros or local people; they take the kaytsa of the dancers and their muwieri and they still dance in a clockwise direction around the fire and around the perimeter of the tuki and meandering. A few minutes later the Ni'ariwamete return to take up their ceremonial utensils to dance again and prepare for the second occasion of the burning of the ocote. This happens four more times inside the circular temple (Centro Ceremonial Tierra Azul, 2017).

From the history of the 'utsi (ocote), the old people say that Takutsi liked to stay in one place, but the ancestors (kakaɨyarixi) wanted to talk to her about how to shape the world; however, Takutsi did not want to go to the other place. Whenever "the commissioners" arrived, Takutsi began to sing, but the commissioners did not know what she was singing, so they sent the smartest "magician" and from him they knew that she did not want to appear with the ancestors. They decided to bring her by force, they grabbed her, but an ancestor [mara'akameWhen they finally saw her coming, they realized that she had already reconstructed herself. Takutsi went inside her cave and the kakaɨyari They got "pissed off": "Let's light some ocotes, let's light some ocotes, let's light them at the entrance, because with the smoke it has to come out! There they lit ocotes so that Takutsi would come out (see video example). However, the goddess was crafty and in her cave she had a hole in the middle of the rock; that is, there was a window that allowed her to breathe and get rid of the smoke and fire.

The chalanes [Ni'ariwamete] of Takutsi extinguished the fire of the ocote tree to protect and shelter her. Takutsi will circulate in her nocturnal walk with her skirt. (kauxe), his walking stick, his mask and his nunutsi (interview with Marcelino González, Tierra Azul, 2017). In another similar myth, Paritsika is trapped by the male animal ancestors of the night and saved by Our Mothers of the Rain and by the voice of the strong Wind, an impetuous wind that rises (Benzi, 1972: 248).

To the sound iconicities that imply a similarity between the nierika and the ceremonial sound reference of the acoustic space of the temples and family adoratories will be called "nierika sonora". "Nierika sound" combines the intermediation and sound intervention of the ceremonial experts in the elaboration and production of exchange offerings, the visionary capacity through prayers thrown into space in circular forms and the dances and sound movements in a circle in which the listener can listen to the sound of the ceremonial offerings. 'enierika resolve in a nierika. Thus, the wixaritari in the dance of the rain they weave a nierika The sound that will be extinguished at five dances by the rain dancers, is danced in a circle and through the sounds in a levorotatory direction. At the edge or the final dance will be extinguished the fire of the great candle, a sonic image or nierika sound through ritual.

This dance is an exercise that combines tension, sensation, kinesthesia, audition, hapticity, situational awareness, alertness and concentration. For Yannis Hamilakis, sensory modalities are infinite, either by an infinity of things, as well as by the contextual situations and places where the sensory experience takes place (Hamilakis, 2015: 43).

Conclusions

On the sonic frontier ceremonial experts wixaritari listen and dialogue with their divinities to negotiate their future and also to continue with life in the face of a society that does not listen as they do. The sonic border is a political ability to establish negotiations in the face of otherness. The sonorous space is located in an imprecise line of the auditory space-time, in a proximity in unspecified places, but the ceremonial experts know who the divinities are. The native category nierika is nourished by the auditory perceptual resource of 'enierika and sounds are placed on the face hixie (at the front) and in other cases the mara'akame listening through the right ear (see Luna, 2023).

The sonic frontier of Waut's communitiesia and Tuapurie is an invisible line of corporeal sonorities that erases the agrarian frontier through the listening of divinized jícaras and the jicareros of Maxayuawita and Tuapurie. By designation and demand of the fulfillment of the yeiyari in the communal norms, is a process of adaptation of ancestry and of their own and shared stories of origin.

In the field of Wixaritari relations with the foreigner or the national society, the sonic border allows communication with the ancestry and is a way to negotiate with those sound corporealities that others cannot hear and in which community and individual interests are at stake. wixarika and its constitutional rights in the collective sphere and its pro-persona rights.

A constant concern among wixaritari is the issue of territorial conflicts with people outside the community. The elders, through their jicarero organizations, express their concern to maintain the union of the group of jicareros and the territoriality of the ceremonial centers conceived in the ancestral histories; that is, to avoid the disunity of the parts of that cosmic deer.

Ceremonial expert listening skills 'enierika (listening-listening) helps to overcome situations related to the dramas of people's lives. wixaritari. The territories that expand are actually those of the non-humans, of the deities. The wixaritari, through their singers, help the deities to reterritorialize themselves, which is achieved through the nierika and, for this reason, the wixaritari are mobilized for the renewal of life.

The Wixaritari are heard immersed in their ceremonial practices and personal experiences.. Human corporeality, objects with agency, buildings and ceremonial practices, are cartographic points that emit sounds, in analogy with a cosmogram. Listeners hear "from there to here" and listen to them "from here to there". Thus the body, the face and the head of the deer-person correspond from the Wixarika anthropology and epistemology to a theoretical object.

For its part, Wixarika territoriality is strongly involved in ceremonial life. The slogan of the community members of San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán: "the land is our mother" evokes the defense of their territory and is closely linked to a network of relationships and intercultural conflicts and conflicts with the State. For this reason, negotiation from the cosmopolitical approach is a position for dialogue and negotiation.

Bibliography

Aceves, Raúl (2009). Simbología, cosmovisión y ceremonial wixarika: diccionario temático. México: Amaroma.

Benzi, Marino (1972). Les derniers adorateurs du peyotl. Croyences, coutumes et mythes des Indiens Huichol. París: Gallimard.

Chamorro, Jorge Arturo (2007). La cultura expresiva wixarika. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara.

De la Cadena, Marisol (2010). “Cosmopolítica indígena en los Andes. Reflexiones conceptuales más allá de lo ‘Político’”, Cultural Anthropology, vol. 25, núm. 2. Trad. Mario Cornejo Cuevas. Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, pp. 334-370.

De la Mora, Rodrigo (2018). El rabel de los cahuiteros. Unidad y diversidad en la expresión musical wixarika: el caso del xaweri y el kanari. Guadalajara: La Zonámbula.

Descola, Philippe (2012). “Más allá de la naturaleza y de la cultura”. Cultura y naturaleza. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, pp. 75-96.

Fabian, Johannes (2019). El tiempo y el otro. Cómo construye su objeto la antropología. Bogotá: Universidad del Cauca.

Fikes, Jay Courtney (1985). “Huichol Indian Identity and Adaptation”. Tesis de doctorado. University of Michigan.

Furst, Peter y Salomón Nahmad (1972). Mitos y arte huicholes. México: sep-Setentas.

Geist, Ingrid (2006). “Teatralidad y ritualidad: el ojo del etnógrafo”, en Ingrid Geist (comp.). Tiempos rituales y experiencia estética. México: Universidad Iberoamericana, pp. 163-177.

Gómez, Paula (2008). “La adquisición de expresiones espaciales en wixárika (huichol)”, Función, núms. 31-32, pp. 267-276.

Gutiérrez Choquevilca, Andrea-Luz (2016). “Máscaras sonoras y metamorfosis en el lenguaje ritual de los runas del Alto Pastaza (Amazonia, Perú)”, Bulletin de l’Institut Francais d’Études Andines (1) (45 ).

Gutiérrez del Ángel, Arturo (2008). “Centros ceremoniales y calendarios solares: un sistema de transformación en tres comunidades huicholas”, en Carlo Bonfiglioli, Arturo Gutiérrez, Marie-Areti Hers y María Eugenia Olavarría (eds.). Las vías del noroeste ii: propuesta para una perspectiva sistémica e interdisciplinaria. México: unam, pp. 288-319.

Kindl, Olivia (2013). “Eficacia ritual y efectos sensibles. Exploraciones de experiencias perceptivas wixaritari (huicholas)”, Revista de El Colegio de San Luis, vol. 3, núm. 5, pp. 206-227.

Kohn, Eduardo (2013). How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley, Los Ángeles y Londres: University of California Press/Library of Congress Cataloging -in-Publication Data.

Hamilakis, Yannis (2015). “Arqueología y sensorialidad hacia una ontología de afectos y flujos vestigios”, Revista Lationoamericana de Arqueología Histórica, vol. 9, núm. 1, pp. 29-53.

Lewy, Mattias (2015). “Más allá del ‘punto de vista’: sonorismo amerindio y entidades de sonido antropomorfas y no-antropomorfas”, Estudios Indiana, núm. 8. Berlín: Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut, pp. 83-98.

Liffman, Paul (2005). “Fuegos, guías y raíces: estructuras cosmológicas y procesos históricos en la territorialidad huichol”, Relaciones. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, año/vol. xxvi, núm. 101, pp. 52-79.

— (2012). La territorialidad wixarika y el espacio nacional. Reivindicación indígena en el occidente de México. Zamora: El Colegio de Michocán, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social.

Lemaistre, Denis (1997). “Le parole qui lie: le chant dans le chamanisme huichol”. Tesis doctoral. París: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

Lumholtz, Carl (1986). El arte simbólico y decorativo de los huicholes. México: Instituto Nacional Indigenista.

Luna, Xilonen (2004). “Música wixarika entre cantos de ‘la luz’ y cordófonos”. Tesis de licenciatura. México: unam, Escuela Nacional de Música.

— (2005). Música y cantos para la luz y la oscuridad: 100 años de testimonios de los pueblos indígenas. México: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas.

— (2016). “La herencia de la diosa del maíz: guía de las calabazas y enfermedad en el rancho parental wixarika”. Tesis de maestría. México: Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

— (2023). “Modos de escucha entre expertos ceremoniales wixaritari. Un estudio de la antropología de los sentidos”. Tesis doctoral. México: Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Martínez, María Isabel y Johanes Neurath (2021). Cosmopolítica y cosmohistoria. Una anti-síntesis. Buenos Aires: sb.

Medina, Héctor (2003). “Las peregrinaciones a los cinco rumbos del cosmos realizadas por los huicholes del sur de Durango”, en Alicia M. Barabás. Diálogos con el territorio. Simbolizaciones sobre el espacio en las culturas indígenas de México, vol. iii. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, pp. 94-104.

— (2014). “El alimento de los dioses: toros y ciervos en la tradición wixarika/ The Food of the Gods: Bulls and Deers in the Huichol Tradition” [09/04/2014]. Cuestiones del tiempo presente | Comida ritual y alteridad en sociedades amerindias-Nouveaux mondes mondes nouveaux-Novo Mundo Mundos Novos-New World New worlds– Coord. Arturo Gutiérrez del Ángel y Hector Medina , 1/15. https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.66707

— (2020) Los wixaritari. El espacio compartido y la comunidad. México:ciesas.

Mier, Raymundo (1996). “Tiempos rituales y experiencia estética”, en Ingrid Geist (comp.). Procesos de escenificación y contextos rituales. México: Universidad Iberoamericana, pp. 83-110.

— (2009). “Cuerpo, afecciones, juego pasional y acción simbólica”, Antropología. Boletín Oficial del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, núm. 87, nueva época, septiembre-diciembre, pp. 11-21.

Negrín, Juan (1977). El arte contemporáneo de los huicholes. Guadalajara: udg-inah-sep.

— (1986). Nierica, Arte contemporáneo huichol. México: Museo de Arte Moderno.

Neurath, Johannes (2000). “El don de ver. El proceso de iniciación y sus implicaciones para la cosmovisión huichola”, Desacatos, núm. 5, invierno, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social México, pp. 57-77.

— (2002). Las fiestas de la casa grande. México: Estudios Monográficos Etnografía de los Pueblos Indígenas de México, Conaculta-inah.

— (2013). La vida de las imágenes. Arte huichol. México: Conaculta.

Pacheco, Gabriel (1995). “Principios generales de la cultura huichola”, en José Luis Iturrioz y otros. Reflexiones sobre la identidad étnica. Guadajalara: Universidad de Guadalajara, pp. 79-93.

Olmos, Miguel (2007). Antropología de las fronteras. México: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte/Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Schaefer, Stacy B. (2002). To Think with a Good Heart: Wixárika Women Weavers and Shamans. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Téllez, Víctor (2011). Xatsitsarie Territorio, gobierno local y ritual en una comunidad Huichola. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán.

Vernant, Jean-Pierre (1985/2001). La muerte en los ojos. Figuras del otro en la antigua Grecia. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Wagner, Roy (2013). “La persona fractal”, en Monserrat Cañedo Rodríguez (ed.). Cosmopolíticas. perspectivas antropológicas. Madrid: Trotta, pp. 83-98.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig (2017). Investigaciones filosóficas. México: unam.

Zingg, Robert (1982). Los huicholes. Una tribu de artistas. México: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas.

Xilonen María del Carmen Luna Ruiz D. in Social Anthropology, Master in Social Anthropology from the National School of Anthropology and History (enah) and a degree in Ethnomusicology by the fam, unam. Seconded for a postdoctoral stay in the Department of Anthropology at the uam-Iztapalapa/conahcyt. His doctoral thesis focuses on a study of the anthropology of the senses: the modes of listening among ceremonial experts. wixaritari. She is co-author of the collection Culturas Musicales de México, vols. i and iiSecretary of Culture. He has published several articles and coordinated books and phonograms for academic and government institutions. He has held various public positions over the years supporting the indigenous peoples of Mexico.