Projecting the Promise: Film and Railroads in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

- Gabriela Zamorano Villarreal

- ― see biodata

Projecting the Promise: Film and Railroads in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

Receipt: September 24, 2024

Acceptance: February 14, 2025

Abstract

This article analyzes a selection of film and audiovisual records documenting two different moments in the history of the Tehuantepec Isthmus Railroad. The materials analyzed include a film on the inauguration of the route by Porfirio Díaz in 1907 and official videos recently produced to promote this work. From perspectives shared in film and infrastructure studies around notions of excess, contingency and uncertainty, I examine how, within the framework of two different political projects that could be understood as antagonistic, these types of materials have constituted artifices that seek to materialize promises of development around plans for regional development and greater national and international integration.

Keywords: cinema, railroad, infrastructure, Isthmus of Tehuantepec, promise

screening the promise: cinema and railways in the isthmus of tehuantepec

This article analyzes a selection of film and audiovisual records of two moments in the history of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railway: a film of Porfirio Díaz cutting the ribbon on the new railway in 1907, and recent government videos on the railway's extension. The article draws on perspectives common in both film studies and infrastructure studies around ideas such as excess, risk, and uncertainty. Within the context of two distinct and contrasting political agendas, it shows how film has been employed to materialize promises of regional development and stronger domestic and international connections.

Keywords: railway, cinema, infrastructure, promise, Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Emulating the astonishing images filmed by just a pair of gaudy movie cameras in January 1907, when President Porfirio Díaz first inaugurated the Interoceanic Railroad in front of an expectant crowd in the port of Salina Cruz, we see in the preliminary tours of the new Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad and in the opening a few weeks later by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in December 2023, how hundreds of hand-held cameras were used to film the new railroad, we see in the preliminary tours of the new Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad and in the opening held a few weeks later by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in December 2023, how hundreds of portable cameras contained in personal cell phones recorded the event and the reactions of the public to hastily broadcast it on social networks.

These images of varied textures and qualities competed with the clear official records, many of which were captured in aerial drone shots that focused on the operators and the monumental machine crossing the Isthmian landscape. Three years prior to this reopening, official media and social networks periodically circulated video reports on the progress of the work and its repercussions in the region; these included the new stations, the longed-for reinstallation of passenger service at affordable prices, the reactivation of cargo service or the articulation of the route with "Poles of Wellbeing Development".1

The main question guiding this article is in what ways the official film and audiovisual records from the beginning of the century xx and the second decade of the xxi have contributed to materialize dissimilar promises of development that have been generated around this infrastructure work. This question involves examining the temporal dimension of the film and railway infrastructures analyzed, as well as their anchorages and resonances in two different historical moments.

By amplifying and recirculating real and prospective images of this infrastructure work, the audiovisual records of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad have served as "aesthetic vehicles" (Larkin, 2013: 329) of promises of economic growth and national and global belonging -whether fulfilled, yet to be fulfilled or failed-, which contribute to forge memories, subjectivities, longings, desires, wishes, rumors and expectations around this work from different state projects.

The analysis focuses on films about the railroad in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec that were produced for promotional purposes: the documentary Inauguration of international traffic in Tehuantepec (1907) about the inaugural tour of the route by Porfirio Díaz, and current promotional videos about the rehabilitation of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad. Despite the different political contexts in which the works were carried out, by reviewing these materials as a whole I identify common elements, resonances, continuities and ruptures that guide official or institutional narratives around the same infrastructure work. Likewise, I examine records of construction supervision and inauguration; images of official personalities and crowds; formal elements in terms of perspective, registration of movements, spaces and effects of closeness or distance; material record of machinery, tools and works; narratives and metaphors regarding notions of promise, mobility, connectivity, modernity and progress; as well as tensions around the traditional and the modern in the documented spaces. I also analyze the political conditions and technological qualities that made possible the recording and circulation of these materials and the temporal dimension of their narratives.

Cinema and railroads: aesthetic vehicles of promise

Several authors have explored the parallel, or even mutually constitutive, relationship between the railroad and cinema as mid-century technologies. xix that drastically influenced modern perception and subjectivity (e.g., Kirby, 1997; Krüger, 2011; Roca, 2000; Wood, 2013). On the one hand, the recurrent presence of the railroad in early filmic records contributed to show it as an iconic technology of modernity, due to its capacity to massively mobilize people and goods and to condense space and time in ways very different from other means of transportation that existed in the century xix (Krüger, 2011). On the other hand, the railroad was a key device to experiment cinematographically with perspective and movement, for example, through the famous "phantom ride", a shot in which the camera was tied to the front of the train -sometimes together with the photographer- to record the movement from there, simulating a subjective view at full speed on the tracks, landscapes and tunnels that it travels through (Krüger, 2011: 13).

Shots of locomotives and tracks were recurrent since the first "views" captured by the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière in the last decades of the century. xix. Trains quickly became the protagonist of other film genres, especially the travelogues or "travel films" that recorded landscapes and picturesque aspects of exotic places; narrative films of romances and action, as well as projections on moving wagons titled Pleasure Railway (Krüger, 2011: 13-16). Trains were also at the center of avant-garde works such as Cine-ojo (1924) y El hombre de la cámara (1926), in which Dziga Vertov experimented with previously inconceivable shots by placing the camera, which for the time was more or less static in front of events taking place in front of it, in a variety of shots and angles inside, above, below and around the train, linked by an agile montage that accentuated the effect of speed and monumentality of the railroad.2

Although these early developments in cinema could be framed in the realm of entertainment, the expansion of this technology resulted as much from experimenting with its possibilities as from complex economic, political and scientific processes. The success of the "vistas" and travelogues produced by the Lumière brothers and by the young cinematographers who worked for them traveling around the world resonated with processes of colonial expansion that increased the fascination with landscapes and peoples conceived from Europe as exotic. At the same time, the arrival of cinematographers and the possibilities of filming in this diversity of locations often served the interests of local elites and powers. One example is that when the Lumière collaborators Bon Bernard and Gabriel Veyre arrived in Mexico in 1896 to promote this technology and record the first views in America, the first screening of their materials was held at a private function for President Porfirio Díaz and his family at Chapultepec Castle. This was followed by public screenings and the filming of about 30 shots in the country, including official and casual activities of Díaz riding horses, with government officials and in parades; some were made in collaboration with early Mexican filmmakers such as Salvador Toscano and the Alva brothers (Miquel, 1997).

Thus, while the views of Mexico were consumed in Europe as exotic aspects of this country, in the Mexican context the cinematograph was not only approved and welcomed by the president, but also Díaz, as part of his modernizing impetus, saw in this technology an opportunity to amplify his image and his works, just as he did with the arrival of photography in Mexico by resorting to the most prestigious photographers to take his portrait (Aguilar Ochoa, 2021).

Although both the cinema and the railroad were emblematic infrastructures of modernity a century ago, it is worth asking in what ways cinema and its variants in audiovisual formats are currently used as propaganda tools to promote the construction or rehabilitation of state works such as the railroad, and what are the political meanings of these images today.

To examine how the links between the railroad and cinema have contributed to expanding promises of development in the Isthmus region in two different historical contexts, I take up Brian Larkin's idea that infrastructures constitute "semiotic and aesthetic vehicles" (2013: 329). This is because both the cinema and the railroad generate "embodied" and sensory experiences, while - similarly to promises of development - they "operate at the level of fantasy and desire. These encode the dreams of individuals and societies and are the vehicles through which those fantasies are transmitted and become emotionally real" (Larkin, 2013: 329). Due to their symbolic and political potential to influence collective imaginaries and fantasies around infrastructures, the promotional images of these works can be considered as "modules or parts of the infrastructure itself", as suggested by Júlia Morim and Alex Vailati (2023: 183) in their analysis of a filmic collection on the construction of the port of Suape in Pernambuco, Brazil, during the 1970s. At the same time, I take up the insistence of authors such as Harun Farocki (2013), Jonathan Crary (2008) and Deborah Poole (1997) to investigate the political, cultural, institutional and technological contexts that make possible the production, circulation and attribution of meaning of images in specific historical moments.

Elements such as contingency, excess, uncertainty and temporality are particularly relevant for the analysis of cinema and railroad technologies. In this regard, in his analysis of the presence of the railroad in cinema produced during the Porfiriato and the Mexican Revolution, David Wood (2013) examines the tension between the impetus to represent the railroad as an icon of "rationality and efficiency" and the ways in which "chaos and contingency" are present in the registration and montage of these images. In the case of Inauguration of trafficWood notes, for example, that the numerous sharp shots of the train in motion, including shots of ghost rideThe images of the train's landscape accentuate the representation of this technology as fast, dynamic and efficient; that is, as a technology capable of fulfilling the promise of "international economic integration" (Wood, 2013: 197). At the same time, shots of the landscape traversed by the train record, almost accidentally, somewhat unpredictable scenes of children bathing in a river, an everyday moment in the local market, or a hut in the blurred landscape that, according to Wood, constitute a "folkloric counterpoint" or, following Doane (2002), temporal and spatial "contingencies" that interrupt the dynamic representation of the railroad (Doane, 2002: 201). The analysis of "contingency" in the cinematic record made by Wood, Doane and other authors, has resonances with the notion of "excess" or "visual noise" identified by some studies in the indexical quality of photography that makes visible material details that, many times, exceed the intentions of the photographers and the temporalities of the moment of recording, thus contributing to the ambiguous and open qualities of these technologies (e.g., Poole, 2005; Edwards, 2012).

Recent studies on infrastructures also observe qualities of "contingency" and "excess" by identifying that infrastructure works are not mere technological insertions with a determined, calculated and predictable function, but "produce new worlds" that entail "unpredictable", "uncertain", "unexpected" and "silent" transformations (Jensen and Morita, 2015; Bonelli and González, 2018). This happens through processes such as "creating new forms of sociality, remaking landscapes, defining new forms of politics, reorienting agencies, and reconfiguring subjects and objects at once" (Jensen and Morita, 2015: 83-85). These reflections, in turn, point to temporal dimensions of infrastructure works and their historical contexts.

Based on these reflections, I pay special attention to how these elements of contingency, excess and uncertainty, which are common to cinema and railway infrastructures, permeate the ways of materializing the promise as luminous, clear and material evidence; or, alternatively, of evading it, overflowing it or reappropriating it from random, blurred, imprecise or opaque elements and details that are insinuated in these same representations and in their specific contexts of production and circulation.

From the Tehuantepec National Railroad to the Tehuantepec Isthmus Railroad

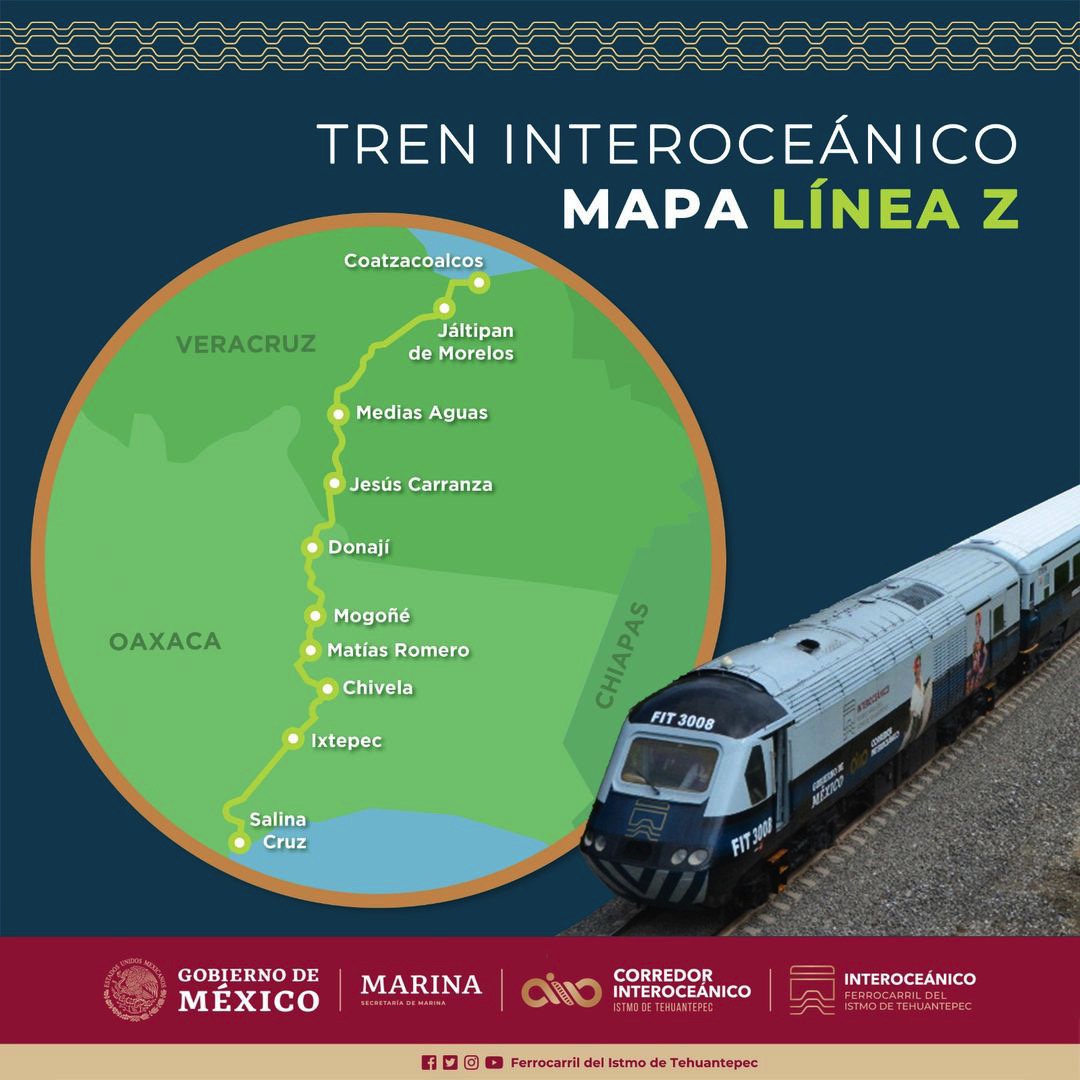

The current Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad project adds to a long history of prospecting that began in 1842, which resulted in the inauguration of the commercial route of the National Railroad of Tehuantepec in 1907 by President Porfirio Diaz (1877-1880 and 1884-1911) in a stretch of more than 200 kilometers between the ports of Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, and Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz. Together with other port infrastructures, this work sought to interconnect the Pacific Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean and, therefore, maritime commercial traffic between Asia and the east coast of the United States.

The habilitation of this commercial route was one of the modernization strategies implemented by Díaz between the late 1880s and 1910. During his mandate, the railroads were key to expand the exploitation of natural resources in different regions of the country and to favor foreign investment and Mexico's integration into the world economy. In this context, the expansion of railroad infrastructure contributed significantly to the productive activation of mining, agricultural, oil and industrial regions in different regions of Mexico between the late 1880s and 1910 (Witker, 2015). Although growth focused on strengthening the construction of the nation state through the paradigm of progress, it favored privatization processes that accentuated the dynamics of dispossession and exploitation of peasant sectors and working classes (Witker, 2015).

After a decade of boom, the Ferrocarril Nacional de Tehuantepec lost relevance due to the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. In 1918, when the contract with the Pearson company was terminated, it became part of the Ferrocarriles Nacionales company, which was nationalized during the government of Lázaro Cárdenas in 1937. Between ups and downs, the Tehuantepec Railroad kept moving throughout the century. xxespecially after its reactivation in 1948 by President Miguel Alemán Valdés. At the same time, this period initiated a policy of repression and demobilization of the railroad union struggles and those of other sectors (Ballesteros Rojo, 2005).

The decades following this modernizing drive between 1950 and 1970 and the subsequent national economic crisis of the 1980s came at the cost of demobilizing and ultimately abandoning workers in state-owned enterprises, leading to the privatization of most of these institutions during the 1990s. Despite privatization, the transisthmian rail route remained central to the prospective plans around the controversial Plan Puebla Panama that was partially implemented between 1990 and 2000 (e.g., Béjar, 2001; Boyer, 2019).

In 1999, the privatization of Ferrocarriles Nacionales was consolidated and Ferrocarril del Istmo de Tehuantepec was created as a majority state-owned company in charge of three lines between Veracruz, Tabasco and Chiapas. Since passenger service ceased operating in the Isthmus in 1999 and until a few years ago, the exclusive cargo service was used clandestinely and with increasing risks by a growing number of Central American migrants in their attempts to transit to the United States. In 2019, as part of his priority projects, the then newly elected President Andrés Manuel López Obrador decreed the creation of the decentralized public agency Interoceanic Corridor Istmo de Tehuantepec (ciit), in which the reactivation of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad (fit) was one of the key projects.3

In addition to seeking to reactivate a strategic region for global trade, the López Obrador administration's objective was that the rehabilitation of the railroad would have a positive impact on the quality of life of the region's populations. To this end, this project was conceived as a key piece of the Development for Wellbeing Plan that López Obrador initiated during his term in office. The Development for Wellbeing model -which some authors frame as part of the so-called "left turn" or "post-neoliberal" in Latin America (e.g., Ackerman, 2021; Cockburn, 2014)- entails a series of policies that seek to remedy the adverse effects of the neoliberal period, among which López Obrador highlights the privatization of national companies and resources, the replacement of the State by the market, inequality and corruption.4 However, as Jenny Cockburn (2014) points out, in practice this rhetoric of rupture results in a contradictory coexistence of progressive and neoliberal policies. In this context, the project to rehabilitate the Isthmus Railway mobilized promises and expectations of a better future; of greater proximity of local populations to the State and, therefore, with services, welfare and greater citizen participation that, to some extent, have been attached to the Fourth Transformation government's commitment to "diversify development". However, as recent anthropological studies on infrastructure in different parts of the world have shown, the implementation of this type of works also, inevitably, accentuates processes of violence, conflict, uncertainty and dispossession (e.g., Anand, Gupta and Appel, 2018; Boyer, 2019). As elsewhere in Latin America, these negative repercussions of development infrastructures promoted by leftist governments involve the paradox of trying to be congruent with the rights and legal personality of indigenous peoples and with environmental protection, while participating in neoliberal global economic logics that reproduce dynamics of inequality and environmental deterioration.5

Thus, the recent projection of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad on an infrastructure project that was generated at the beginning of the 20th century, has been a major step forward in the development of a new railroad. xx gives this project a complex temporal density. By analyzing in the following sections promotional materials of this route in two historical moments, I pay attention to the ways in which these representations nurture and feed back into processes of memory and expectation of the future, alluding to specific promises of development.

Porfirio Diaz at the inauguration of Tehuantepec international traffic

In his classic article on the inauguration of a bridge in Zululand in 1940, anthropologist Max Gluckman (1940) proposes this event as a site of broad texture and ethnographic complexity in which he observes the presence of multiple actors and their interactions. Furthermore, Gluckman wonders what this bridge itself means, what types of connections it establishes, what its materiality is. Seventy years later, contributing to a more consolidated debate around infrastructures as sites of anthropological analysis, Penny Harvey analyzes the inauguration of a highway in southeastern Peru (2005). Focusing on the space and temporality of this work, she reviews the long-term history experienced by the people of the region around the road; many of them physically participated in its construction and experienced the delays, interruptions, and expectations. He contrasts this long-term experience with the fleeting presence of President Alberto Fujimori who, paradoxically, arrived to inaugurate it by helicopter. Harvey examines how the physical presence of this authority meant for the local inhabitants a way of making the promises of development tangible.

I take up here the reflections of these two anthropologists on the political and symbolic relevance of the acts of inauguration of infrastructure works in different moments and geographies to investigate how the propagandistic narrative is articulated in the filmic record of Díaz's inaugural act on the Isthmus Railroad. Twenty years after the first visit of the Lumière cinematographers to Mexico, Salvador Toscano (1907) -the most important filmmaker and exhibitor of the time, who also happened to be an engineer- produced the newsreel film Inauguration of international traffic in Tehuantepec (1907). Between 1898 and 1910, Toscano also made records of President Díaz in daily and official activities.

Due to a certain closeness of Toscano with Díaz and the ruling classes and also because of the president's interest in using modern photographic and film technologies to promote his image, Toscano obtained the official concession to document this inauguration along with the Alva brothers and a handful of Mexican cinematographers and journalists (De la Vega, 2013). The documentary is perhaps one of the first edited films about the inauguration of an infrastructure work, even already using certain cinematographic language beyond views, as Aurelio de los Reyes observed in his spoken commentary to this film (Toscano, 1907). Although De los Reyes (1986) documented at least four films around this work, the only one that has been recovered is Toscano's (De la Vega, 2013: 89-90). There was also the exhibition of these films between February and April 1907 in important national theaters in Zacatecas, Guadalajara and Mexico City (De la Vega, 2013: 91-94). This brief information on production and exhibition aspects of the film allow us to locate its positionality in the historical moment in which it was made, for example, that it was made possible by Toscano's privileged access to film governmental acts, that it had a relatively wide circulation -fostered by the interest of Díaz and other politicians and businessmen in this work- and that its content was attractive to the audiences of the time. At the same time, as De la Vega suggests, the relevance of this film at the time reveals the attention of filmmakers of the time on official events and not on the multiple social movements, such as Magonismo, that opposed the environmental and political impacts of the construction of the railroad; nor did they show the repressions they faced, although shortly after Toscano masterfully documented the Mexican Revolution (2013: 86-87).

Inauguration of traffic consists of 13 short chapters marked by descriptive intertitles that, as a whole, narrate Porfirio Díaz's maiden voyage on this railroad route, which for the first time made possible in Mexico the direct transfer of goods and passengers between two great oceans, from the port of Salina Cruz to Puerto Mexico (today Coatzacoalcos). Each chapter consists of one or more uncut views lasting between 30 seconds and one minute.

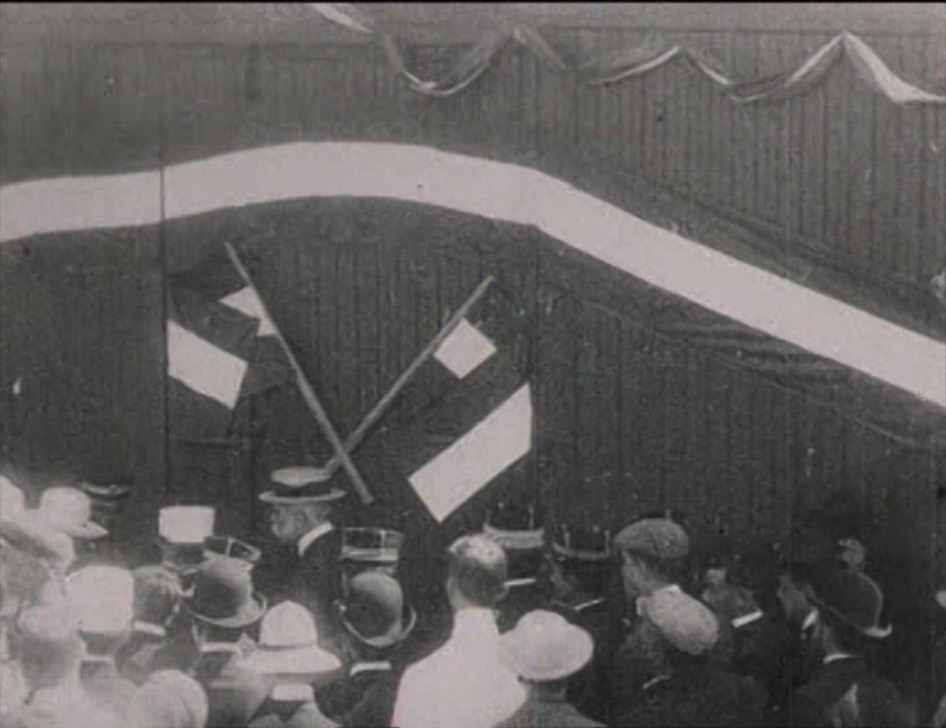

After beginning with a shot of a moving ship in the port of Salina Cruz, a sequence shows Díaz opening the gate of the port's station to allow the train's first departure. The event is attended by officials, military authorities, train workers, a large group of soldiers with musical instruments and local spectators. The president's attitude is aloof despite being surrounded by people at all times, most of whom bow to him and remove their hats. Emulating the constant views of the era of train departures, a new shot shows the railroad in all its splendor as it leaves the station, as the workers and the public look on in amazement, some also turning in surprise to the camera. The camera then pans to the "retinue of Oaxacans and the State Military College," who slowly file past the camera. The train then heads to the Arizonan steamship from where sacks of sugar are unloaded with a crane to be deposited in a van adorned with tricolor ribbons and flags. The scene shows workers at work and later the retinue accompanying Díaz, while a crowd struggles to watch as the president seals the van for the trip across the ocean.

These opening scenes are followed by others along the route: a record from inside the carriage of a riverside hut from which people watch the passing of the railroad and the movement of the train marked by the unmistakable steel bars supporting the bridge over which it crosses. Then follow three rather picturesque scenes. In keeping with the cinematic conventions of the time, one view records a group of people leaving mass in Tehuantepec: men in calzonzon and manta shirt walk down the steps putting on their hats, while women wear the distinctive Tehuantepec flare, huipil and petticoat, accompanied by girls in shawls and boys in hats. The camera then pans to the market to observe a group of women selling their wares in baskets, counting money, some watching the camera with curiosity and children peeking their faces very close to the apparatus smiling and watching attentively. The last scene of this type shows a family bathing in the river next to Tehuantepec: an old woman with a naked torso is seen on her back soaping herself, another woman is bathing, while the children play in the water and on the beach.

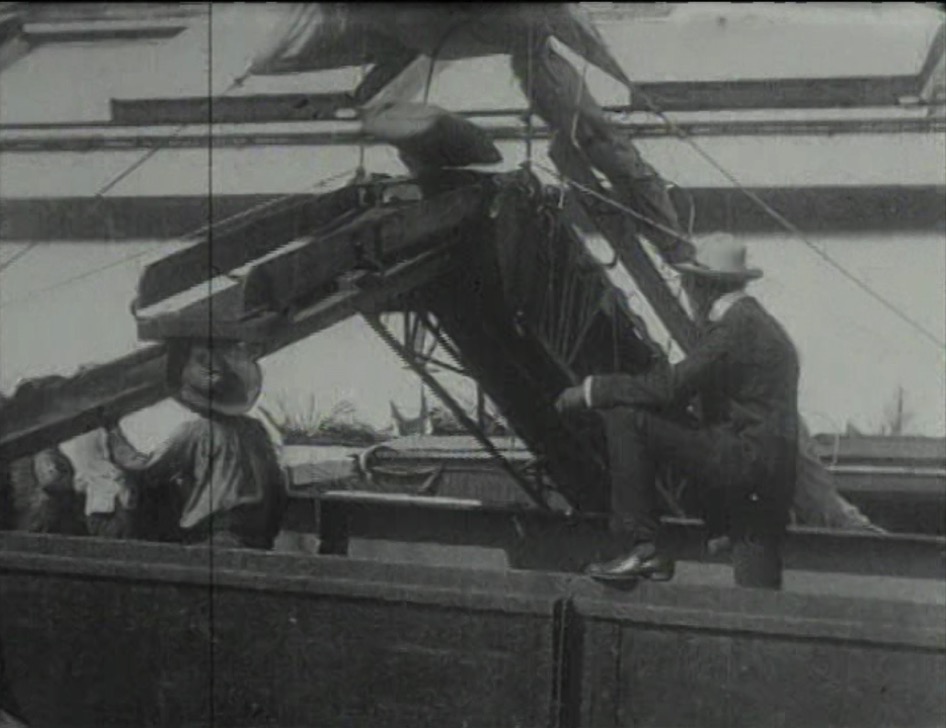

This scene is followed by a behind-the-scenes view of the train parked on a bridge while a group of journalists walk to the side of the track to board it. The camera is very close, filming them from the front, so they interact with it: they smile, observe, pose playfully as they move forward in line. Three of them are holding large-format folding cameras. The penultimate one, with a thick cigar lit between his lips, deftly climbs into the carriage, propelling himself with both arms. This scene, which was probably filmed after the group went down to portray and observe the river, allows a glimpse of the image and news makers, who are normally invisible in the records, thus adding another layer of complexity to the inaugural event.

The last scenes return to focus on the "Señor Presidente" after arriving in Puerto Mexico, where the crowd gathers again in front of the decorated van that had left Salina Cruz. The president and his entourage climb stairs to the door, he removes the seal and leaves. Another view shows a crane with a mechanical device to remove the cargo from the van and slide it into the McGabe cargo carrier. Next to the crane, a concentrated worker, dressed in a blanket shirt and hat, pushes a sack, taking care not to let it fall. By the time the second sack goes up, a black-suited supervisor approaches, stops, puts his foot over the edge and watches the action. A third sack is propelled off, followed by 13 others, with a speed that was probably unheard of at the time, as the worker follows them to the forklift. Then there are shots of people attentively observing the action from other angles: military personnel in one section; passengers on the ship watch from a balcony on the side. As De los Reyes points out in his spoken commentary to the film, the steamer's passengers are upper class: the men in suits; women and girls in long dresses and white hats. For their part, the workers below, already in groups, continue directing the unloading.

The final sequence shows a panoramic view of the port from the steamship as it pulls away while the crowd looks on. A Mexican flag flies from the top of a building. Finally, evoking the opening shot, another steamer is seen passing by with a smoking chimney and then the horizon of sea and sky divided by a breakwater of rocks.

As De los Reyes observes, in these views it is clear that Toscano was experimenting with different possibilities for recording movement. On the one hand, he positions the camera in front of unexpected situations and everyday moments of the villagers; he also records the movement of large modern objects such as trains, ships and cranes. On the other hand, movement is experienced by placing the camera fixed on moving objects, especially ships and trains. These shots show the astonishment and fascination for what is happening and what the camera can capture, whether everyday or extraordinary.

In the following section, in analyzing a series of short videos that documented the rehabilitation and inauguration of the Tehuantepec Isthmus Railroad between 2019 and 2023, I focus on the remarkable continuity with this astonishment and experimentation with the recording of movement more than a century after this first documentation of the railroad in Mexico, despite its realization and circulation in totally different political and technological contexts. Above all, there remains a fascination with making visible the movement created by technologies that, like the train, seem to repeatedly embody promises of the future, although there also remains a reiteration of the presence of the presidential figure at the head of these works.

"Renace el Istmo": documenting railroad rehabilitation

More than a century after the first inauguration of the Tehuantepec Railroad was recorded by a few cameras as a pioneer work of documentary in Mexico and exhibited in the main national movie theaters, the new inauguration of this same route is massively and instantly transmitted in short digital video formats that can be consulted on personal devices, which now serve as the main channels of state propaganda. Starting in 2020, official news and videos about the rehabilitation of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad began to be transmitted through two websites managed by the Mexican government: the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Interoceanic Corridor website (Corredor Interoceánico del Istmo de Tehuantepec) and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Interoceanic Corridor website (Corredor Interoceánico del Istmo de Tehuantepec).6 and that of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad (fit).7 While these sites publish formal and synthetic information, the fit also disseminates through three social networks: Facebook, Instagram, and x.

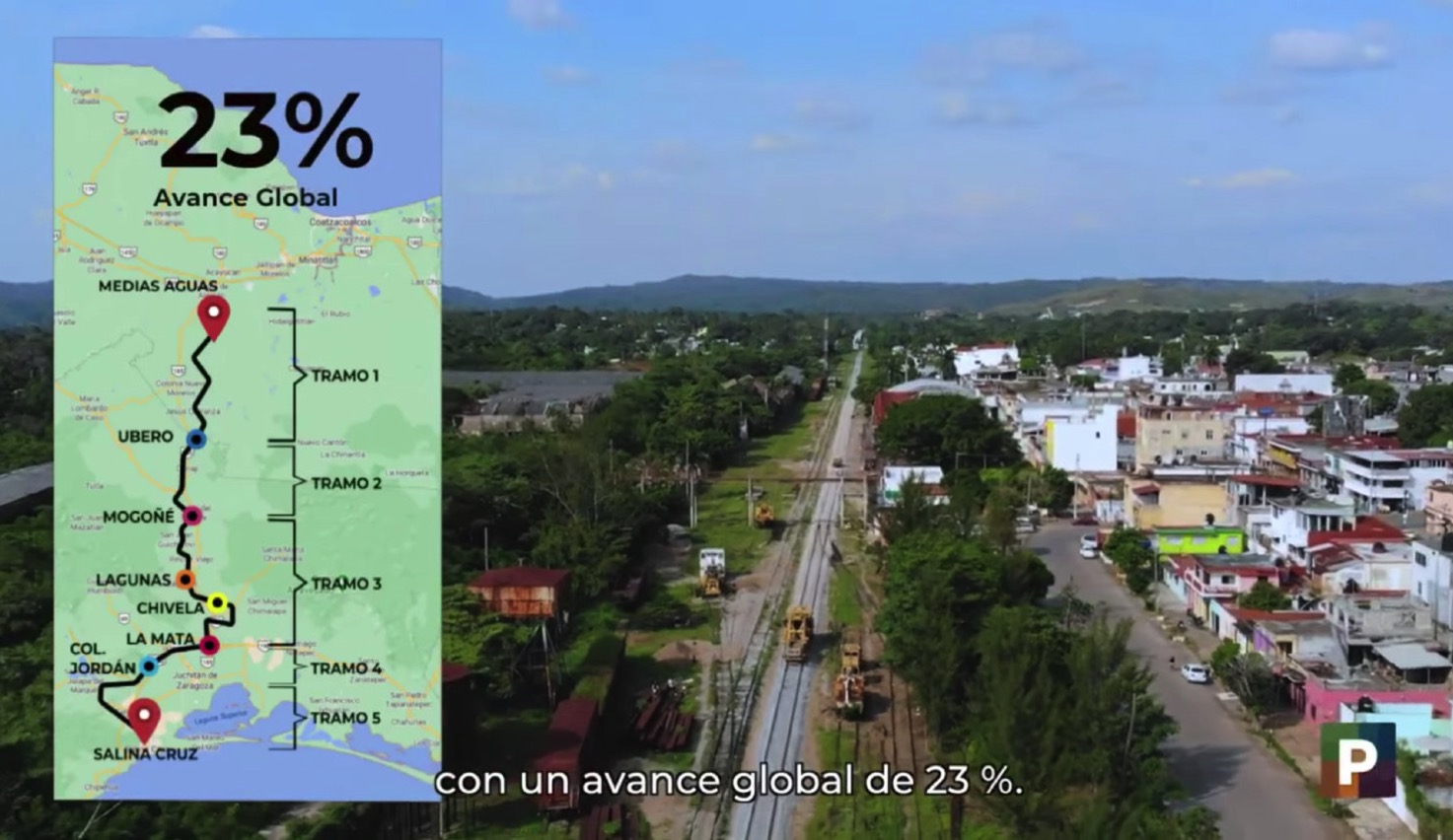

The reactivation of this route has so far not involved the production of an official documentary,8 but short video reports on their progress and impacts. In this section I analyze a selection of video reports from the fit based on monitoring of posts on the official Facebook site before, during and after the December 2023 inauguration of the Line. z of fitThe company's main line of business, which interconnects the ports of Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos, is the one that connects the ports of Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos.9

The formal recording of work progress - including the use of drones, animated mock-ups and editing of materials - is carried out by members of the company's communications teams. fitThe multiplicity and versatility of these records to be transmitted in raw form or to be reused in edited materials with structured narratives characterize the fragmented and unfinished aspect of these new forms of producing and consuming propaganda about the President. The multiplicity and versatility of these records to be transmitted raw or to be reused in edited materials with structured narratives characterize the fragmented and unfinished aspect of these new ways of producing and consuming propaganda about this infrastructure work.

Taking advantage of the format and popularity of Facebook, the official Facebook page of fit has consistently published videos ranging from 20 seconds to five minutes in length, photographs and infographics since the work began to take shape in late 2020, thus creating material evidence, always in the form of timely and clear fragments, that the work is progressing. In most of these videos a female or male narrating voice persists, which is combined with homogeneous and soft instrumental music. The videos intersperse drone shots that accentuate the majesty of the works in progress with shots of workers concentrating on their work, deftly operating the machinery that also unfolds in awe through close-up or wide shots. Some videos include digitally animated maps that effectively show the unfolding of the works on the territory. In these pieces, the promise is enunciated in the narration from two temporalities: with sentences constructed in the future tense, such as "it will allow the passage", "it will be a reality"; but, also, when narrating the concrete progress of the works, with sentences in the present tense, using verbs such as "they continue", "it has an advance", "there are active works". The temporality of the promise is also identified in the type of images used. While the first videos interspersed, as evidence in the present tense, video recordings of construction work and works in progress, in 2022 the use of digital models was incorporated more and more frequently to graphically explain technical details of the upcoming construction of certain works.

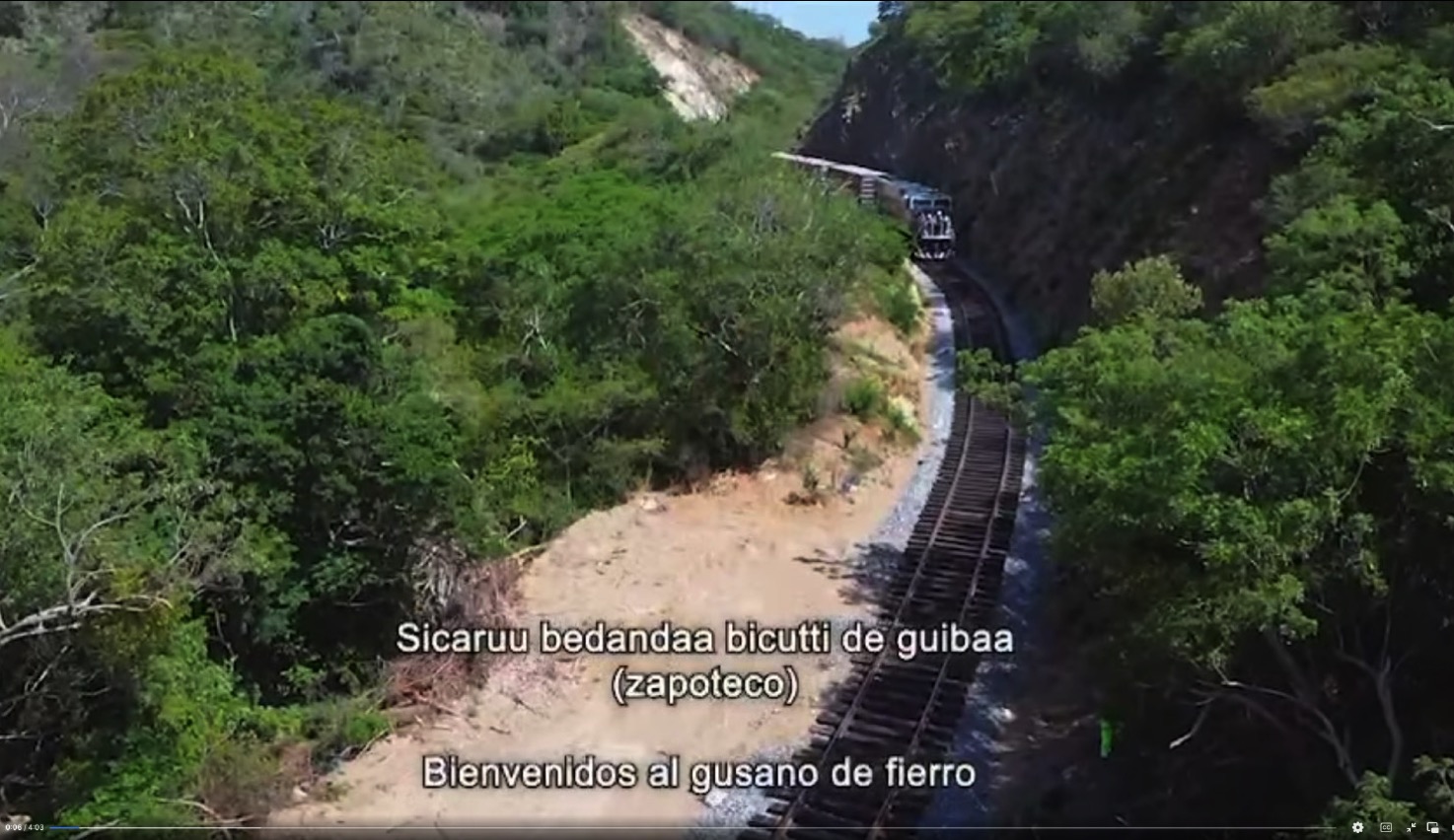

After three years of periodical publications of this type of progress, video reports began to announce the conclusion of the works, through transmissions of test runs. In addition to spontaneous official records of the supervision tour carried out along the entire route by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador on September 17, 2023,10 a four-minute video report on this event was produced.11 After the logo of the Secretary of the Navy, which appears forcefully with a metallic sound, a male voice emits a phrase in Zapotec whose subtitles translate as "Welcome to the iron worm", while a locomotive is seen from an aerial shot approaching in the middle of a landscape of hills.

This image is followed by a series of shots of López Obrador boarding the train and then greeting, sending kisses and hugs from the carriage door to the crowd watching him from the tracks, while an institutional male voice announces that "a new stage begins in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec". The report format then follows with general aerial shots of the train advancing into the bush connecting with renewed ports. An animated map of the region is also shown to indicate the ten sites where development poles will be installed. This is followed by a world map indicating with red lines the connections to the Isthmus from Asia; with green lines the connections to the east coast of the United States and with white lines the maritime connections from Central and South America. A new map of southern Mexico traces the railroad routes still pending to interconnect with southern Chiapas, Tabasco and sections of the celebrated Tren Maya.

The report then goes on to detail the work that was done to complete the line and specifies the pending work for the new routes. The end of the report explains, always illustrating with images of communities and residents, how these works are linked to social and economic works in the localities, in order to reaffirm the "integral, sustainable and inclusive development for all", stating that "the rebirth of the Isthmus is beginning".

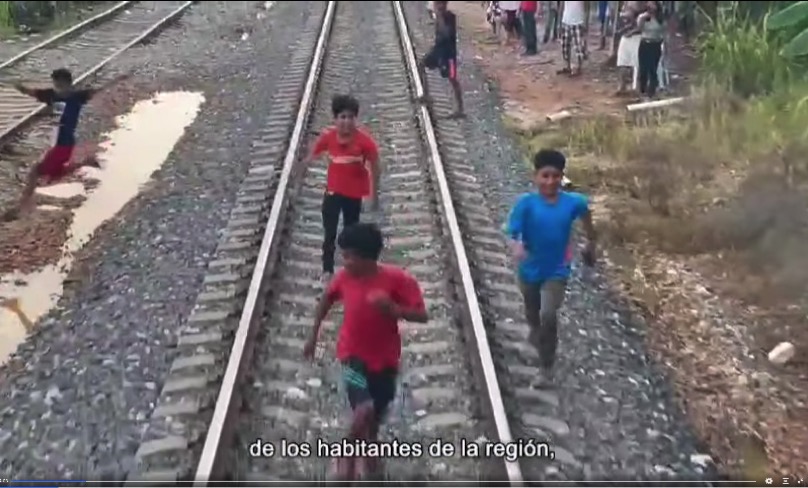

Thus, while what has already been achieved and what is in process is shown with record-evidence, the future is sketched in maps. At the same time, a novel component are the references to the impacts on the local population, which are demonstrated with images of works and services in localities - parks and streets, assemblies and economic activities; but also in the references to language and territory. The new promise that opens up in "this new stage" is clearly stated at the end of the video-report: "integral, sustainable and inclusive development". In this way, the future is also outlined in random or "contingent" moments that are capitalized in the narrative of the promise, for example, by capturing a group of children running after the train or the spectators waving flags next to the tracks as a way of greeting and thanking the passing of the train and the visit of the president.

A type of record very similar to the one just described served as the basis for the video on the inauguration of the work on December 23, 2023.12 It combines the president's casual interactions with the people that produce an intentional effect of closeness to the people, unlike, for example, the film in which Porfirio Díaz inaugurates the same route and does not show any interaction with the crowd. However, similar to the 1907 documentary, this one focuses at all times on the presidential figure: his voice is heard throughout the piece and his interactions with the high command of the Army, the Navy and other officials are seen, but he also interacts with many other sectors such as the workers and engineers and, above all, with the townspeople -railroad workers, women, men, boys and girls who receive him enthusiastically.

Unlike the documentary on Díaz in which the president maintains a serious and solemn attitude, this video, like many other official media, shows a smiling, spontaneous, warm and physically close president. Something that stands out in this piece is the way in which the president's speech is placed in a "historical" present in which the yearnings of more than five centuries to unite the oceans are crystallized.

At the same time, this present makes constant nods to the future shown in the images of children and villagers, accentuated by the final phrase of the speech: "Thinking of those who come after us, this project is for them". This emphasis on the local population is reinforced by the inclusion of ethnic or regional elements such as shots of women, old women and girls, wearing colorful traditional costumes, which are also emulated in the iconic and giant image of the tehuana together with a jarocha that adorns the front carriage of each train. The local tinge is also produced by the use of traditional Isthmian band music at the beginning and end of the clip. These nods to local identities differ from the previous video reports referred to in the first part of this section, which focused on showing technical and material advances of the work outside of any social or historical context.

Thus, the first phase of the Interoceanic Railway focused on making visible the centrality of this work, through the passenger service already enabled, which symbolically aims to repair the neoliberal dispossession of the privatization of Ferrocarriles Nacionales in the late nineties, to fulfill the promise of "integral, sustainable and inclusive development" in the region. On the other hand, the materials released in 2024 point to the new promise of connecting the region with global trade in which the freight railroad is presented as the "backbone of the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, improving the logistics of the supply chain in the southeast of the country."13 The videos in this regard include recordings of trains with renovated containers circulating in the landscape or unloading at ports, as well as didactic animations detailing the amount of cargo or the type of products transported by the vans.14

By consulting these publications in chronological order, I identify a temporal narrative that transits between the enunciation in 2020 of a promise of interconnection located in the future -still at an abstract level- and the articulation of a present in 2024 that fosters amazement for the materialization of the works, which is related to significant historical events over more than a century of railroad operation in the region. The narrative also seems to transit between the promise of regional development, in which the passenger railroad is presented as a key piece, to the promise of global interconnection, for which the freight service is proposed and evidenced as the "backbone".

In this narrative, congruent with a post-neoliberal approach to diversify development, the "contingency" of everyday and spontaneous images is rather capitalized to season the effect of the president's closeness to the people. On the other hand, while the ethnic elements aim at exalting the cultural richness of the region, they also suggest a certain continuity with multicultural neoliberalism, that is, with governance strategies that recognize cultural rights as ways to neutralize opposition and adverse economic impacts of development policies (Hale, 2002). At the same time, there are other contingencies that remain outside the frame of these productions, but that overflow this coherent and optimistic narrative, often also from the use of audiovisual media and unofficial social networks. Thus, these pieces leave out of the frame the mobilizations and blockades that several communities carried out to interrupt the construction of the works because they did not agree with the consultation processes and agreements that were carried out in the region, the repression of these protests,15 the strategic decisions not to install stations in towns with a history of mobilization or the apparently logistical decisions to keep out of the train facilities the growing flow of Central American migrants and local people who, in the past, complemented their economies by transporting and selling their agricultural products on the old passenger trains.

Conclusions

From the earliest filming of railroad infrastructure works in Mexico, it is notable that these combine the material monumentality of these works with a glorification of the presidents, military and state officials who make them possible. At the same time, this record includes shots of the workers who build them and the masses who embrace them, while documenting processes of construction or rehabilitation to produce evidence of improvement between before and after. From the assemblage of these events, narratives of the president arriving alongside the train and of the fulfillment of development promises are reiterated, as in the case documented by Penny Harvey in Peru (2005). In this essay I have inquired into the ways in which cinema and its contemporary audiovisual variants amplify this promise, reiterate it and transport it to other spaces and times.

The two cases analyzed respond to dissimilar historical contexts and political projects. By combining two of the iconic technologies of modernity, the cinema and the railroad, Inauguration of international traffic was one of Mexico's first cinematographic works to be produced and consumed as evidence of the integration of the emerging Mexican nation into the global economy; an integration that, however, excluded most of the region's inhabitants and repressed their mobilizations. More than a century after this production, the video reports on the rehabilitation and inauguration of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railroad are framed within a new development discourse that, while also appealing to modernity, growth and global economic integration, emphasizes the possibilities of favoring a region that was dispossessed by the effects of neoliberalism, especially by the privatization of the railroads undertaken by the government of Ernesto Zedillo in the 1990s.

Thus, despite the historical, technological and political differences in the materials analyzed, I have identified continuities that reveal resonances and nuances about the role of film and audiovisuals in shaping the promise of development by documenting infrastructure works. The materials analyzed seek to produce visual odes and metaphors around infrastructure, its materiality, and the technologies or machinery always in action that enable its operation. There also continues to be a fascination with exploiting the possibilities of the train to record movement, whether from within or without. Likewise, the landscape continues to be represented as a central and complementary aspect of the infrastructures. On the other hand, there is a suggestive play with picturesque scenes that, due to their unexpected and somewhat uncontrollable character, are the ones that most condense the notion of "contingency". Some pieces include shots of local towns and scenes as ways of contrasting the movement of progress -sublimated in the moving train- with the apparent static of local life, as observed by David Wood in relation to Toscano's film (2013). And in the more recent ones produced after López Obrador's inauguration, the clips intentionally include these local scenes, highlighting ethnic elements such as music, dress and language, to emphasize that the villagers are the main actors of the promised progress. At the same time, some of these shots seem to overflow the narrative and escape from the edges of the frame to reveal the multiple contingencies that are disputed around these works and that, many times intentionally, are left out of the narrative.

Bibliography

Ackerman, Edwin (2021). “Post-neoliberalismo realmente existente en México”, Política y Gobierno, vol. 28, núm. 2, pp. 1-8.

Aguilar Ochoa, Arturo (2021). “Mirando más allá al héroe de la república y al fotógrafo del imperio. Porfirio Díaz y la fotografía”, Fotocinema. Revista Científica de Cine y Fotografía, núm. 22, pp. 23-48.

Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta y Hanah Appel (eds.) (2018). The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham-Londres: Duke University Press.

Ballesteros Rojo, Manuel (2005). “La guerra de Vallejo, o los días que conmovieron a Matías Romero”, en Víctor Cérbulo Pérez, Manuel Ballesteros Rojo et al. (eds.). ¿No oyes pitar el tren? Un acercamiento a la historia y la cultura de Matías Romero Avendaño, Oaxaca. Matías Romero: Ayuntamiento Constitucional de Matías Romero/Conaculta/pacmyc/Secretaría de Cultura de Oaxaca, pp. 29-49.

Béjar Álvarez, Alejandro (2001). “El Plan Puebla Panamá: ¿desarrollo regional o enclave transnacional?”, Observatorio Social de América Latina, núm. 4, pp. 83-105.

Bonelli, Cristóbal y Marcelo González Gálvez (2018). “The Roads of Immanence: Infrastructural Change in Southern Chile”, Mobilities, vol. 13, núm. 4, pp. 441-454.

Boyer, Dominic (2019). Energopolitics: Wind and Power in the Anthropocene. Durham-Londres: Duke University Press.

Calla, Ricardo (2012). “tipnis y Amazonia: contradicciones en la agenda ecológica de Bolivia”, Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, vol. 92, pp. 77-83.

Crary, Jonathan (2008). Las técnicas del observador. Visión y modernidad en el siglo xix. Madrid: cendeac.

Cockburn, Jenny (2014). “Neoliberal Governance, Developmental Regimes, and Party Systems in Postneoliberal Latin America: A Review”, Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, vol. 39, núm. 1, pp. 157-169.

De la Vega Alfaro, Eduardo (2013). “Prensa, cine y poder en la última etapa de la dictadura porfirista: los reportajes de El Diario y el caso de inauguración del tráfico internacional en el Istmo de Tehuantepec (1907), de Salvador Toscano Barragán”, en Lucila Hinojosa Córdova, Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro y Tania Ruiz Ojeda (eds.). El cine en las regiones de México. Monterrey: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, pp. 83-122.

Farocki, Harun (2014). Desconfiar de las imágenes. Buenos Aires: Caja.

De los Reyes, Aurelio (1986). Filmografía del cine mudo mexicano. Ciudad de México: Filmoteca de la unam.

Doane, Mary Ann (2002). The Emergence of Cinematic Time. Cambridge-Londres: Harvard University Press.

Edwards, Elizabeth (2012). “Objects of Affect: Photography beyond the Image”, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 41, núm. 1, pp. 221-234.

Ferri, Pablo (2022). “Un conflicto de tierras en Oaxaca pone en evidencia el tren del Istmo de López Obrador”, El País, 27 julio. Consultado el 21 de abril de 2025. https://elpais.com/mexico/2022-07-27/un-conflicto-de-tierras-en-oaxaca-pone-en-evidencia-el-tren-del-istmo-de-lopez-obrador.html

Gluckman, Max (1940). “Analysis of a Social Situation in Modern Zululand”, Bantu Studies, vol. 14, núm. 1, pp. 1-30.

Hale, Charles R. (2002). “Does Multiculturalism Menace? Governance, Cultural Rights and the Politics of Identity in Guatemala”, Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 34, núm. 3, pp. 485-524.

Harvey, Penny (2005). “The Materiality of State-Effects: An Ethnography of a Road in the Peruvian Andes”, en Christian Krohn-Hansen y Knut G. Nustad (eds.). State Formation. Anthropological Perspectives. Londres: Pluto Press, pp. 123-141

Jensen, Casper Bruun y Atsuro Morita (2015). “Infrastructures as Ontological Experiments”, Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, vol. 1, pp. 81-87.

Kirby, Lynn (1997). Parallel Tracks: The Railroad and Silent Cinema. Durham-Londres: Duke University Press.

Krüger, Ralph (2011). “La fascinación temprana por la técnica y el espectáculo: el phantom ride en los comienzos de cine”, Arkadin, núm. 3, pp. 12-20.

Larkin, Brian (2013). “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure”, Annual Review of Anthropology, núm. 42, pp. 327-343.

Manzo, Diana (2024). “Declaran culpable a defensor que se opuso a parque industrial del Interoceánico en Oaxaca”, Primera Línea, 31 de enero. Consultado el 21 de abril de 2025. https://www.primeralinea.mx/2024/01/31/declaran-culpable-a-defensor-que-se-opuso-a-parque-industrial-del-interoceanico-en-oaxaca/.

Miquel, Ángel (1997). Salvador Toscano. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara.

Morim, Júlia y Alex Vailati (2023). “O museu suape: reflexões sobre a contramusealização dos acervos visuais”, Iluminuras, vol. 24, núm. 65, pp. 172-199.

Oliveira Ferreira, Hélio Júnior et al. (2021). “El papel de Brasil en la iirsa: neoestructuralismo y neoextractivismo”. Tesis de maestría. Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, sede Ecuador.

Poole, Deborah (2005). “An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies”, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 34, núm. 1, pp. 159-179.

— (1997). Vision, Race, and Modernity. A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Roca, Lourdes (2000). “Ferrocarril e imágenes en movimiento: ¿por un México nuevo?”, en Victoria Novelo y Sergio López (coords.). Etnografía de la vida cotidiana. México: Miguel Ángel Porrúa, pp. 117-148.

Wood, David (2013). “Film, Time, and the Railway in Porfirian and Revolutionary Mexico”, en Araceli Tinajero y J. Brian Freeman (eds.). Technology and Culture in Twentieth-Century Mexico. Alabama: University of Alabama Press, pp. 197-213.

Witker, Jorge (2015). “Liberalismo e interés nacional en el porfiriato”, en Raúl Ávila Ortiz, Eduardo de Jesús Castellanos Hernández y María del Pilar Hernández (coords.). Porfirio Díaz y el derecho. Balance crítico. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, unam, pp. 173-188.

Filmography

Ibarra, Epigmenio y Verónica Velasco (2024). Tren Maya. Argos Media Group.

Moran, Giselle (2024). “México en el centro del mundo. Corredor Interoceánico del Istmo de Tehuantepec”. Real Estate Market.

Toscano, Salvador (1907). Inauguración del tráfico internacional de Tehuantepec (1907), en Filmoteca de la unam. Oaxaca. Recopilación de documentos cinematográficos, existentes en la Filmoteca de la unam, sobre la vida política, social, económica y cultural del estado de Oaxaca, 2005. Colección Imágenes de México. unam/dgac. dvd.

Vertov, Dziga.(1924). Cine-Ojo. Mezhrabpomfilm.

— (1926). El hombre de la cámara. Dirección de Fotografía y Cine de Ucrania (vufku).

Gabriela Zamorano Villarreal is a researcher at CIESAS Mexico City and holds a PhD in Cultural Anthropology from The City University of New York (2002-2008). Among her publications are the books: Indigenous Media and Political Imaginaries in Contemporary Bolivia (University of Nebraska Press, 2017, award inah Fray Bernardino de Sahagún) and Ethnographies of "On Demand" Films: Anthropological Explorations of Commissioned Audiovisual Productions, co-edited with Alex Vailati (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2021). Directed the documentary Cordero Archive (Mexico-Bolivia, 2020). In 2023 she co-coordinated the project "Restoring Territory and Memory: Samples of Visual Archives in Michoacán", selected as part of the initiative "Reimagining Futures, (un)Archiving the Past". Her current project is entitled "Prospecting over ruins: visuality, railway infrastructure and indigeneity in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec".