Mérida's carnival in 1913, social contrasts of a city through the lens of a German photographer

- Laura Machuca Gallegos

- ― see biodata

Mérida's carnival in 1913, social contrasts of a city through the lens of a German photographer

Receipt: September 24, 2024

Acceptance: January 22, 2025

Abstract

Photographs of the city of Mérida, Yucatán, taken in 1913 by Wilhem Schirp, a German amateur photographer, are the axis of analysis to reflect on the representation of this city, particularly during carnival, as an event of memory. It shows that the festive cycle was used by the elites to show off their wealth at the height of the henequen boom, while appealing to the "popular" and the "traditional". In this context, the photographer's lens captured the contrasts and social inequalities in a festival that was supposed to be one of investment.

Keywords: carnival, elites, henequen, memory, Merida

the mérida carnival in 1913: urban social contrasts in the lens of a german photographer

Photographs taken in Mérida, Yucatán, in 1913 by amateur German photographer Wilhelm Schirp serve as a starting point for analyzing the city's representation. The article focuses particularly on photographs taken during Carnival. During this memorable celebration, and despite frequent references to the "popular" and "traditional," the elites showed off their wealth during the peak of the henequen (agave fourcroydes) boom. Schirp's lens captures the social divisions and inequalities present even during a celebration that ostensibly subverts the social order.

Keywords: Carnival, Mérida, henequen, memory, elites.

Carnivals still survive in many cities around the world, and one of them is Mérida, Yucatán, on the peninsula of the same name.1 In the carnival -or "the party in reverse", as Daniel Fabre (1992) has called it-, people mask themselves, disguise themselves and confuse genders. Local power struggles are also reflected, "social distinctions resurface and make sense in the heart of the most lavish urban carnivals" (Fabre, 1992: 93), in which some watch and others represent.

Based on the photographs taken in Mérida by Wilhem Schirp, a German amateur photographer, and taking as an axis of analysis that most of his material corresponds to 1913, we reflect on the representation of society that his lens left us and on the processes of memory that evoke the events and places he portrayed, some still in force, such as the carnival. Much work has been done on the importance of photography, especially family photography, to give birth to processes of historical memory. I also consider that these photos by Schirp, those of this festival and others, contribute to memory, in the manner of Maurice Halbawachs (2004: 50): "each individual memory is a point of view on the collective memory". For him, history, more than dates, is "everything that makes a period stand out from others" (2004: 60), and the carnival festivities are the living history he refers to, that bridge between past and present that individual memory and the physical testimony that photography leaves us of an era becomes collective memory that reveals those particular details of a historical period, in this case that of the henequen boom in Yucatán.

The first thing that strikes the eye in these photos is the colorfulness of the floats, the whiteness and elegance of the costumes, the bearing of the women (who, for the most part, were the ones parading). In spite of being black and white photos, some of the faces look pale and contrast with the brown faces that can be seen in other floats in which women dressed in the "mestiza" costume, the traditional Yucatecan dress, can be seen. Likewise, we can see the support staff, perhaps Mayans, with their impeccable white clothes and some with a striped apron. Image 1 consists of two images, the one on the right side shows the strength of the social difference; perhaps more than portraying the three ladies in the carriage, the photographer's objective was to show the four men at the front of the procession. Although they are all correct, two are barefoot and two are wearing shoes. The quality of the clothing and hats is contrasting, as other elegant gentlemen in suits can be seen in the back. Children can also be seen, such as the one posing on the left of image 1, who, by his clothes and hat, we could think that he slipped in with the consent of the photographer, perhaps in spite of the ladies in the carriage.2

John Mraz (2007: 116) wrote that "If one knows how to interrogate them, photographs document social relations, they speak about class, race and gender, both by showing their very existence and by depicting their transformations". This is precisely why Schirp's photographs are of enormous interest, as he was a keen observer and managed to capture the complex social forms of Yucatecan society on several occasions, perhaps entirely circumstantially in the case of the carnival photos.

In Emmanuel Leroy Ladurie's (1994) interpretation, every carnival has a social utility. Luis Rosado Vega (1947: 92) in his essay on the carnivals of Mérida writes that in spite of "all the urban hierarchies [...] the carnival swept everything and set everything on fire", this celebration meant a total break from everyday life. According to Joan Prat's characterization (1993: 290), the carnival was a "ritual of ostentation", "a bourgeois entertainment characterized by the massive occupation of the streets and in a reflection of the same bourgeois and citizen power that drives and welcomes it"; the elements of contestation are hardly observed and the "exhibition and spectacle" predominates. These characteristics seem to be attached to that of Merida. In particular, I have found of special importance the approach of Milton Araújo Moura (2009), who, relying on Michel Foucault, considers photographs as "testimonies of power". Schirp, then, with his foreign vision -although he was not hired by these power groups, which is not the focus of interest of this work- knew how to capture the contrasts of this society very well, bequeathing us his photos.

Our idea is based on other authors who had already written about carnival. It is worth mentioning that the carnival has been held since colonial times and that it has adapted to the times. Pedro Miranda (2004: 284-285) suggests that since the middle of the xix the purpose of the authorities, with the support of the press and the elites, was to control carnival entertainments with the aim of bringing about "civility" and respect for "public morals". He starts from the idea that, during the Porfiriato, it went from being a popular celebration to being an organization of the elite: "the people had become spectators whose only function consisted of observing or participating in the workers' or friends' societies formed to enter the world of carnival entertainment" (2004: 455). On the other hand, Silvestre Uresti (2022) makes an interesting historical review on the development of the carnival of Mérida and affirms that from 1902 to 1909 and until 1914, it was "the Spanish-Yucatecan power elite", as he calls it, who organized this important festival, leaving aside the popular. Both authors agree that, in these years, Mérida's carnival was considered the most lavish in Mexico and, according to Miranda (2004: 459), comparable to those of Nice, Venice, Havana, among others.

Mérida was not a unique case. For example, the Feria de Valencia was a proposal devised by the bourgeoisie to show off their power by organizing dances and social events exclusively for them, despite the fact that it was disguised as popular (San Juan, 2022). They are parties that result in a display of the elite, as Pierre Bourdieu (1998: 52) has described it very well:

Economic power is, in the first place, a power to put economic necessity at a distance: it is therefore universally asserted through the destruction of wealth, ostentatious spending, wastefulness and all forms of luxury free of charge. Thus it is that the bourgeoisie, by ceasing to make of all existence, in the manner of the court aristocracy, a continuous exhibition, has constituted the opposition of the profitable and the gratuitous, of the interested and the disinterested under the form of the opposition that characterizes it [...].

Wilhem Schirp in Merida

Wilhem Schirp (born in Aachen, Germany, in 1886 and died in Mexico City in 1948) arrived in Yucatan in 1905, hired by the Siemens & Halske company. In fact, he arrived with his brother Peter, who had a much higher position, as Wilhem was the cashier and Peter, the director of the company. Siemens & Halske was in charge of providing electric power service to the city, because the Compañía de Luz y Fuerza Yucateca had not been able to pay debts it had incurred (Durán, 2015a).3

It is worth mentioning that by the turn of the century xx dry gelatin-silver bromide plates were common for the negative, which allowed for a reduction in exposure time and subsequent development. At that time, new sensitized papers also arrived for direct copies and developing (Newhall, 2002: 126). Cameras no longer needed tripods and were smaller in size. In his history of photography, Beaumont Newhall (2002: 129) indicates that technical progress made it easier for amateurs to dabble in photography.

As reported by Waldemaro Concha et al., in Photographers, images and society in Yucatan, In 1841 the first photographer arrived in Yucatán, Baron Emmanuel von Friedrichstal, followed by John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood, who introduced the daguerreotype; they are considered part of the first stage of travelers and adventurers. In the second half of the century xixAt different times, several photographers -foreign and local- developed their work, and it even became a professional activity. At different times, several studios were set up, competing with each other. Towards the 1870s they also began to venture into outdoor photography, less common due to the challenges involved (weight of equipment, hot climate, human personnel, etc.). In the last quarter of the century xix At least 15 photographers are known, although undoubtedly the most recognized and the one who managed to support himself in this activity was Pedro Guerra since 1877.

Don Juan Schirp, Wilhem's son, narrates the following:

I remember my father, with his 1900 model camera, with his "tripod", his "black cloth", to cover the camera, and his magnesium powder shutter "device", to "give light" to the night photos [...] he brought his camera from Germany, he always used it [...] There were already many new models of photographic cameras, but "my old man", he only used his "drawer". 4

The collection consists of an 81-page photo album with 250 images on paper. The album includes annotations identifying the person or place and the shutter speed; there are 391 digital images. Some of the photos (86) correspond to the period 1913-1914, and are the most interesting because they show aspects of daily life.5 These are photos for family use. Several themes stand out: photos of the 1913 carnival, his visit to Uxmal, the season in Telchac, his family. About the city, his interest focused on the Peón Contreras Theater, the Parque del Centenario (dating from Porfirio Díaz's visit in 1906), some muddy streets, outside the progressive picture of the rich part of the center, and the former town of Itzimná (now a colonia near the center). More than the mansions themselves, he was attracted by the gardens and nature, perhaps because of some evocation of the land where he came from.6

Merida at the beginning of the 20th century

To have an approximation of the Merida of the beginning of the century xxWe will use the eyes of two Europeans who visited the city, which was booming thanks to the planting of henequen, a raw material used to make rope for the shipping industry. Hundreds of henequen haciendas worked the "green gold".7 Part of the million-dollar profits were possible due to the exploitation of labor, not only Mayan, but also Korean and Yaqui, among others.

In 1902 the book by Ubaldo Moriconi was published, Da Genova ai deserto dei mayas (Ricordi d'un viaggio comerciale), which includes a chapter dedicated to the city of Mérida. Likewise, in 1906 Maurice de Perigny's article, "Une ville florissante des tropiques au Yucatán: Mérida" (2015) was published. The Frenchman Maurice de Perigny was a count interested in exploration and travel; on the other hand, the Italian Moriconi was another type of traveler, because as a businessman he was looking for markets to do business; not in vain his book is subtitled "Memories of a commercial trip".

Merida, at the turn of the century xxYucatán was as described by De Perigny (1906): "A flourishing city of the tropics", since henequen had brought great prosperity to the city. According to the census, in 1900 it had 57,162 inhabitants and in 1910, 62,447; in total, Yucatan had 339,613 inhabitants.8

The Italian Moriconi dedicated several chapters of his book to the city of Mérida, where he arrived at the beginning of 1900. The first thing that caught his attention were the festivities, especially those of August, dedicated to Santiago, and those of October, dedicated to the Christ of the Ampoules. He referred that the greatest dangers of Merida were the black vomit, some swamp fever and the heat. He said that the worst thing was the rainy season, because the streets became impassable, so businessmen had to use cars. He complained about the mosquitoes, the lack of drinking water and the incessant ringing of bells. He saw many beggars, mostly "old Mayans". As for the numbered streets, he warned that people preferred the old names, which were represented in wood or stone and were figures of crosses, saints or animals like the elephant. He also dedicated a long space to the subject of the lottery. He recognized Mérida as an intellectual center for its convents, its Literary Institute, the Seminary Library, the Archaeological Museum, the Circus Theater, a monumental theater and the beauty of some buildings such as the cathedral and the house of Montejo, as well as the publication of The Merida Magazine.9

He informs us that several commercial companies were formed after the business war (1899-1900), but what most caught his attention was a restaurant "worthy of any European capital": La Lonja Meridana which he describes as a "rare bird in these distant lands". He does not fail to mention the hospitality and generosity of the Yucatecans towards foreigners, regardless of nationality or race.

De Perigny, on the other hand, wrote a short review of his trip in the journal A Travers le Monde10 (1906). He describes the deplorable conditions of Yucatán in the recent past, especially due to the ravages of yellow fever, but acknowledged that Mérida, from being a muddy and unhealthy "sewer", with the government of Olegario Molina from 1902 onwards had become "a charming little capital. All the streets had been asphalted, wide avenues had been opened and 'superb' buildings had been erected [...] of which the largest cities would be proud".

For De Perigny, Mérida had lost its importance since colonial times and had kept only the cathedral and Paseo de Montejo as relics of its former splendor, until the henequen boom changed everything. The money made from the profits was used to build "magnificent and grand houses, those exquisite houses of the tropics with their inner courtyard full of flowers, the patio, and their arcades all around".

About the society he indicated that it was "delightful, always hospitable to foreigners, and for those who distinguish, sincerely cordial," no doubt alluding to the elites. He described the Mayas and mestizos as "sweet, educated, faithful, remarkably honest". He mentions the construction of two hotels, which would not only receive commercial agents, but tourists were also expected to visit "the admirable ruins" (referring to Uxmal). Thanks to the fact that the streets had been paved, there were 600 cars; for a population of 60,000, he considered that number to be very high. Thus, this once desolate city had become an interesting and lively town, especially in October and during carnival.

In 1913, in Europe the ferments of the future war were just beginning. Tibet proclaimed its independence from China and the Ottoman Empire renounced its European possessions and recognized the independence of Albania; this situation led to the explosion of successive wars that year, known as the Balkan Wars. For Mexico, 1913 was a fundamental year, especially politically. After the assassination of Francisco I. Madero and José María Pino Suárez and the commotion known as the tragic decade, Victoriano Huerta came to power. Shortly after, Venustiano Carranza's Plan de Guadalupe would disown him as president. That year also saw the assassinations of Serapio Rendón, Adolfo Gurrión and Belisario Domínguez. Zapata disowned Pascual Orozco as head of the Liberating Army of the South and Pancho Villa took Ciudad Juarez (Betancourt and Sierra, 1989).

Although all this news reached Yucatán, in the peninsula they had become accustomed to the fact that, due to the distance from the centers of power, the interests were different. Merida was one of the most economically active cities in the world. The henequen business was at its best. Commercial activity was essential, hence in 1913 a list was published with the names of the main businessmen. A book of the time summarized the professional and educational scene of the city:

As far as the intelligentsia is concerned, the capital of Yucatán is a cultured city. There are about two hundred lawyers, more than one hundred and fifty doctors and a similar number of notaries, engineers, pharmacists and teachers of primary and secondary education [...] The modern scientific movement has also built in it a well-organized public library [the Cepeda Peraza], an archaeological museum, a botanical garden, several meteorological observatories and special cabinets of educational corporations, all centers of public accessibility that spread intellectual knowledge on a not inconsiderable scale. There were four newspapers, one official and three for information: "la Revista de Mérida", "la Revista de Yucatán" and the "Revista Peninsular", plus the official newspaper (Salazar, 1913: 135).

There were two bookstores: Manuel Espinosa y E. and La Central, owned by Jorge Burruel, which even sold books in French. There was also an important cultural life. On carnival days, these movies were advertised in the movie theaters and in La Revista de Yucatán: Fault and atonement (in seven parts), The cursed daughter, The anarchist Luhí (in two parts), The ghost of the night (in two parts), Revenge of the manufacturer (Danish series in six parts) and The last embrace (in six parts as well), among others. It was a time when cinema had already established itself as a true entertainment industry.

Origins of carnival and choreographic societies

Mérida's carnival has its origins in the 20th century. xvi. In the city ordinances of 1790 it is mentioned that men dressed as women and that oranges were thrown in the squares.11 It is known that the carnival festivities lasted three days because of an 1830 bando that prohibited games that disturbed the public tranquility, such as throwing oranges, eggs or water and painting the walls. In addition, the use of masks was penalized and it was forbidden to ridicule religion by dressing up in religious costumes.12 In less than a hundred years these practices had been eliminated.

It is known that five important groups of members (known as choreographic societies) were in charge of organizing the carnival, both the floats and the contingents, as well as the daytime and nighttime dances that took place daily. This issue is important because power and the enormous social segmentation come into play here. Those same societies had begged and recommended their guests to attend with carnival costumes "in order to restore the sympathetic notes of our ancient carnivals" (The Yucatan Magazine, Saturday, February 1).

Manuel Dondé Cámara founded the Unión in 1847, which included medium-sized merchants, professionals and civil servants. The Liceo, founded in 1870, belonged to the economic elite. The two rivaled each other in luxury and ostentation at the parties they organized almost every night of carnival, which were open not only to members, but also to outside guests. The mestizo choreographic societies that emerged during the Porfiriato were Paz y Unión and Recreativa Popular, formed by mestizos with resources and who tried to replicate the "white" societies. Paz y Unión was founded in 1887 and was composed of artisans; in 1891, after differences between members were bridged, they created the Recreativa Popular. The use of the mestizo costume for the anniversary and Easter dances was obligatory. The members of Paz y Unión even organized a dance in honor of Porfirio Díaz when he visited the peninsula in 1906, which he attended with his entire retinue (see Martín Briceño, 2014: 88-90).

In 1913 there were La Unión and El Liceo, which had been divided into two: El Liceo de la 59 and El Liceo de la 62, destined to "the most elegant of our society" and in whose meetings, they boasted, "champagne" was profusely circulated. On the other hand, Paz y Unión and Recreativa Popular claimed the presence of the mestiza. The mestiza and the mestizo in Yucatan have a very clear presence. Each of these societies had their own carts and their own routes.

Luis Millet and Ella Fanny (1994) analyze the process in which a group of non-Maya (peninsulares, Creoles and mestizos) adopted the Maya costume and suggest that this was mainly due to the climate, which "was [and is] very hot". As they explain, at first the hipil was limited to the home setting; however, by the mid-century xix Men and women of the middle and upper classes in some towns and in the city began to wear the "mestizo" costume in certain festivities; that is, the Mayan hipil became sophisticated with the terno, a cross-stitched embroidered costume with a characteristic background called fustan, accompanied by gold jewelry and the typical rosary (in filigree).

For Lilian Paz (n.d.), the mestizo woman adapted the terno to European fashion in order to differentiate herself from the Maya, to gain status and publicly flaunt it, as did the upper class, which ended up adopting and legitimizing it. Millet and Fanny argue that this happened after the "caste war" crisis,13 because from the perspective of the bourgeois, in order to establish new alliances, it was better to present Yucatán as mestizo and eliminate the figure of the Maya. Marisol Domínguez (2017: 261-262), in her essay on the social landscape in Pedro Guerra's photography, also puts her attention on the Yucatecan mestizo, part of Guerra's clientele, a part constituted by the hacienda Indians and the so-called "pacifics" who marked a difference with the "rebels" and called themselves mestizos, as those who had some "racial" mixture.

Let us remember that carnival was born within a society that made sharp divisions of class and race, as it was installed and developed by privileged groups in the center of Mérida, in neighborhoods where the Maya population only entered the houses as servants. Thus, the mestiza began its participation in fiestas and carnivals as a form of mockery, but, as Millet and Fanny (1994) argue, what began as a transgression eventually became normalized. For a long time the use of the hipil was restricted to Maya women and was a marker of class and race that, when accepted by women of other classes and races in the festive order, functioned, according to them, as "the bridge of social reform".

Although the presence of traditional dress was affirmed by the mestizo societies, as the saying goes, they were "together, but not mixed", since the mestizo societies could only visit the bourgeois ones by invitation.

Chronicles of carnival days

The 1913 carnival was held from Friday, January 31 through Tuesday, February 4, as recorded by La Revista de Yucatán. The radius of action of the derroteros was from Plaza de San Juan to Plaza Grande and from Mejorada to Santiago, along Calle 59, in downtown Mérida. Until then it was a place of residence for the elites, who would gradually begin to move north; the wealthiest would move to the newly opened Paseo de Montejo. As Umberto Eco (1989: 17) has written so well, the modern carnival "multitudinous is limited in space: it is reserved for certain places, certain streets, or framed on the television screen".

In order to understand the social construction of the carnival space, the text by Roberto DaMatta (2023) is very useful, who works on the way in which space is delimited by means of borders; he also considers that for each society there is a "grammar of spaces and temporalities". There is the time of everyday life, in which "the normal rules of naming and work ensure the maintenance of hierarchy and rigid boundaries between the people who represent these positions in the development of ordinary life, but in the '....'".entrudo [Portuguese name for carnestolendas] and carnival these positions can be perfectly reversed" (2003: 7). The interesting thing about the Yucatecan case is that the carnival space maintains social differences.

Another relevant aspect is that we know the names of the people on the floats, at least the ones that the journalist from La Revista de Yucatán considered it pertinent to record; we have even recorded some of them. For those who are not from Yucatán they will be only names and surnames, but in the peninsula these attributes have a particular weight; on the other hand, although we would not need to know the names of those who appear in several of the photos, by consigning them the figure and the name are linked, thus passing to a concrete character who participated in the carnival from anonymity to identity.

Several photographers recorded the carnival. Pedro Guerra -the city's official photographer- also covered the event for The Yucatan MagazineHis participation is very important, since a large collection of his work survives and is kept by the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.14

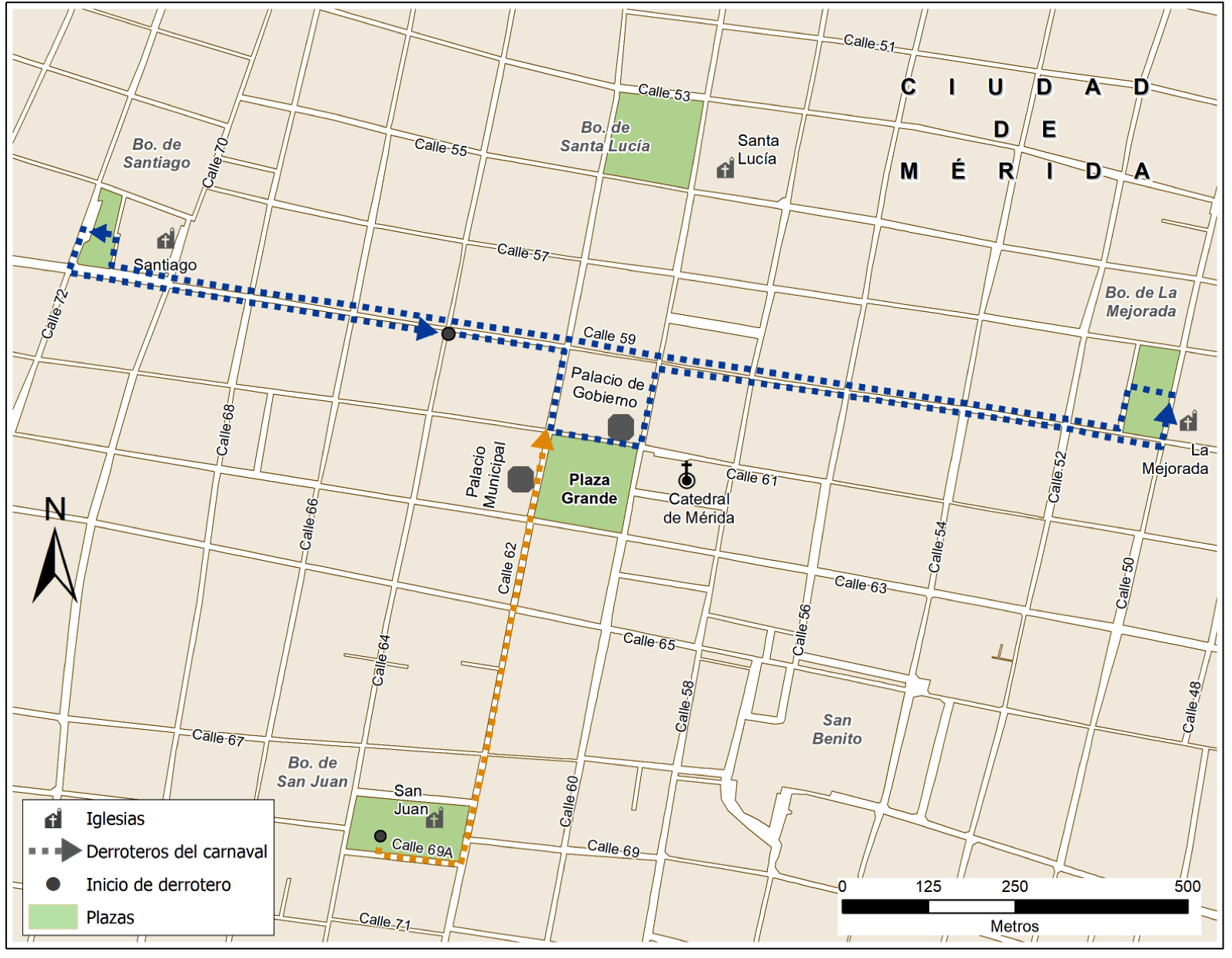

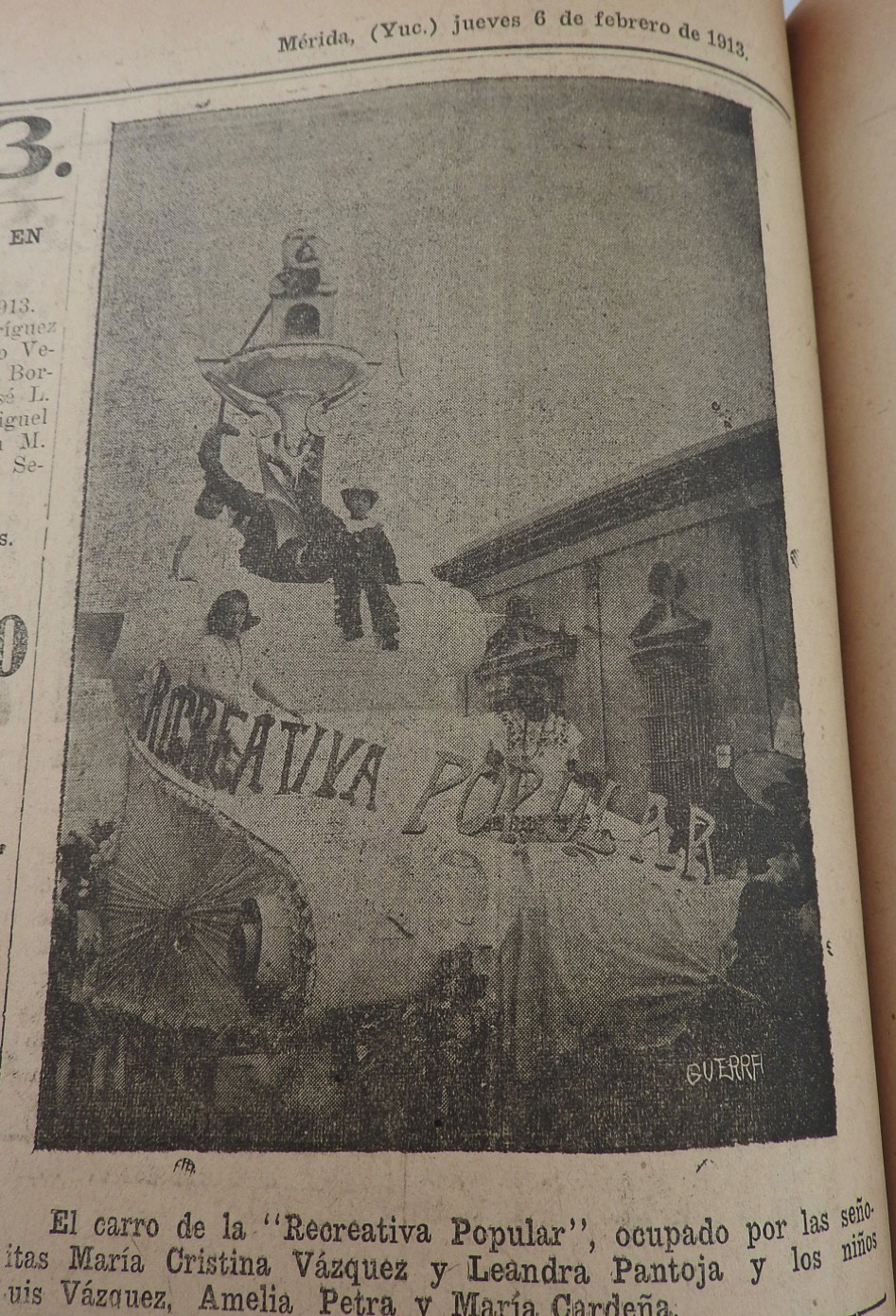

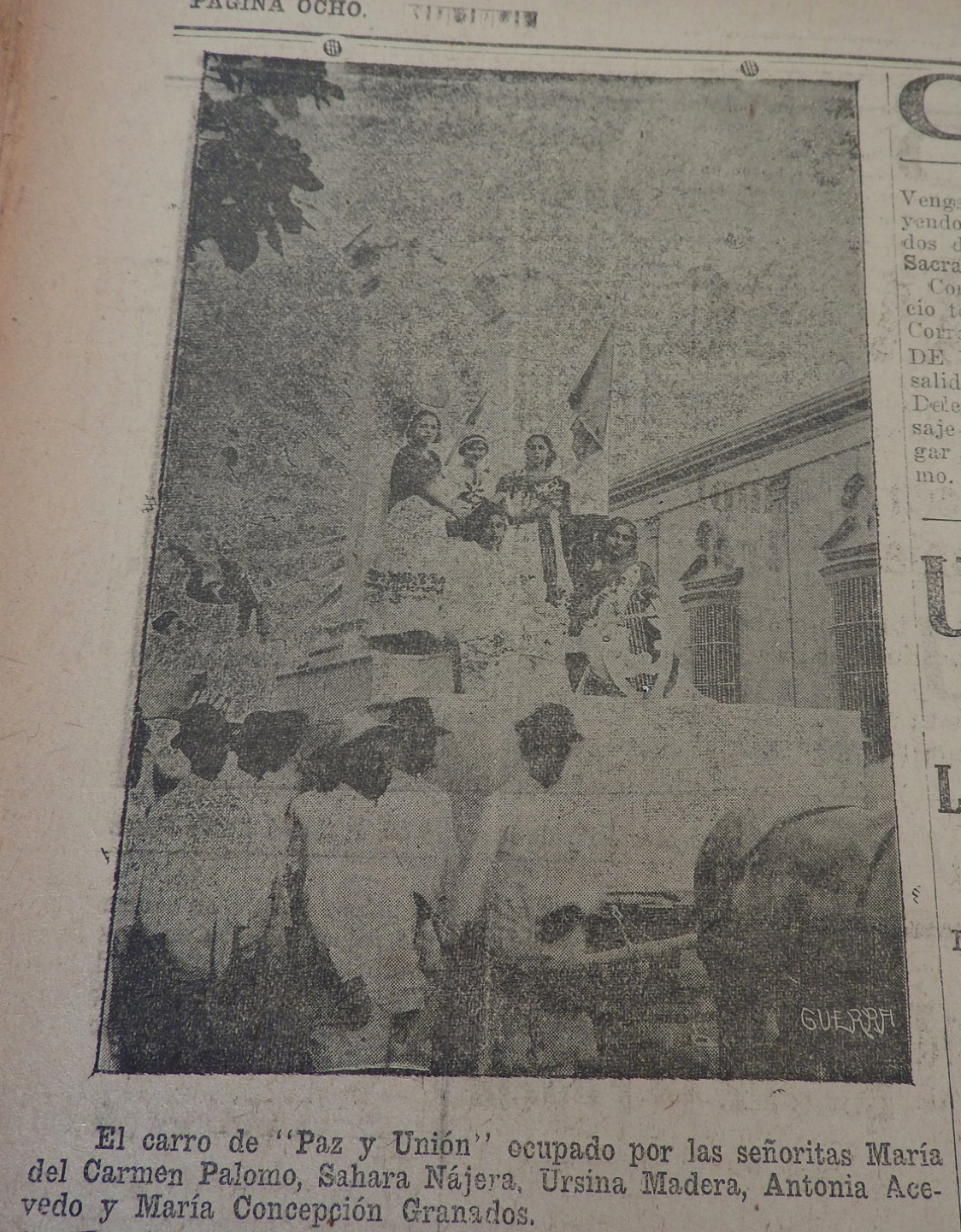

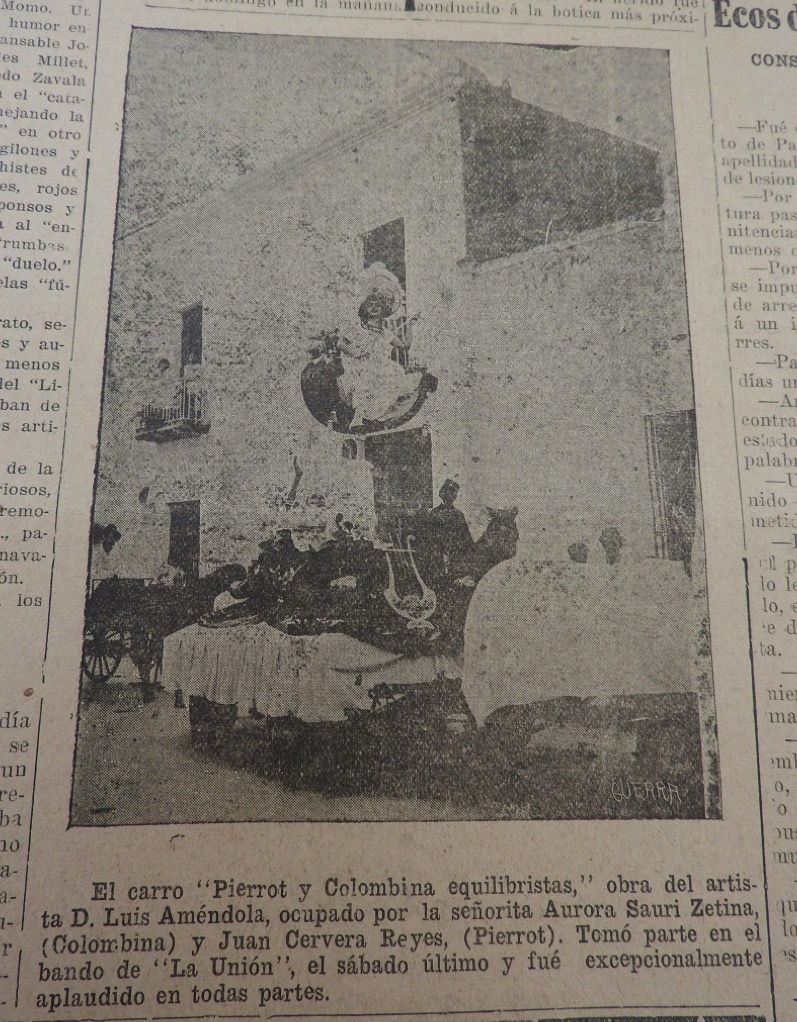

At least three photos published in The Yucatan Magazine coincide with those of Schirp: the Pierrot and Colombina, Paz y Unión and Recreativa Popular. The focus is on the wagons and their protagonists, although in the Paz y Unión one some companions are also seen (see "Annex"). Perhaps the biggest difference with Guerra's photos is that the latter was hired, while Schirp took them "for pure documentary or aesthetic pleasure, of his own free will, detached, in principle, from any immediate application" (Kossoy, 2014: 101).

The Alva brothers were also in Mérida in 1913; they are recognized among the first Mexican documentary filmmakers and at that time they were screening at the Circo Teatro Yucateco,15 where films were broadcast. They filmed the dynamics of the city and in particular made a recording of the battle of flowers on Tuesday, February 4, which apparently was widely broadcast. Unfortunately, the Alva brothers' visual material on carnivals in Mérida and other Yucatecan subjects is no longer known (Aznar, 2006: 57). Another photographer who was in Mérida during those days was the American F. M. Steadman,16 who was located in close proximity to the office where Schirp worked. Siemens & Halske was located on 61st Street (between 46th and 48th) and Steadman stayed at 467 61st Street.

On Thursday evening, January 30, the series was inaugurated with the Union Fantasy Party, attended by more than 200 couples in fancy dress. La Revista de Yucatán He said that there was a variety of music, such as sevillanas, malagueñas and jotas, and named all the ladies who performed the dances; he mentioned that the orchestra was at the height of the carnival, because there were many people and the "splendid ambigú" that was served.

On Friday the 31st the Paseo del Corso began at 8:30 p.m., organized by the society the Liceo de Mérida; it started from its building on 59th Street, number 519, went to 62nd Street, then to Plaza Grande, Mejorada, Santiago and back again to the starting point. The streets were illuminated with hollow wire gasoline bulbs. The march was opened by a group of cyclists, then continued by the gendarmerie and a carriage decorated in a canopy-like manner, in which the king and his pages rode, accompanied by marching bands, comparsas and an endless line of cars, carts and buggies.

On Saturday, February 1, at 5:30 p.m., in the park of San Juan (then called "Velázquez"), the bando of the choreographic society La Unión started, accompanied by cyclists, the mounted gendarmerie and a band of drums and bugles. To it belonged the first float, according to the newspaper chronicle, with swan figures, but there is no photo. It was followed by the float of the Paz y Unión society which, according to the chronicle in The Yucatan MagazineIt also "attracted attention because of the good taste used in its construction, as well as its simplicity", since it represented work and "the Fine Arts" and indicated the name of the author and the ladies who presided.17

In the float two enormous square Corinthian columns are observed. At the back there are some figures like semicircular blades, which perhaps gave it a turn, and if you pay attention, you can read the words "Paz y Unión" (Peace and Union). The float was occupied by Miss María del Carmen Palomo, who held an olive branch, symbol of peace, and Misses Sahara Nájera, Ursina Madera, Antonia Acevedo and María Concepción Granados, who wore the terno. The three girls standing on the float seem to pose for the photographer. There is a large male audience around them (see "Annex").

The Recreativa Popular represented in its cart a mythological griffin on a roll of paper, carrying a cup in its jaws (see "Annex"). The figure in matte paper is only described as a "chinesco" representing a bracero. It was occupied by the ladies María Cristina Vázquez, Leandra Pantoja, dressed in terno, whose necklaces stand out; and by the children Luis Vázquez, Amelia Petra and María Cardeña. The boy Luis appears to be dressed as a cowboy, and the girl Amelia wears a white dress. The mestizas came to stay and institutionalized their annual presence (see Reyes, 2003: 104-112).18 Another peculiarity of image 3 is the children looking towards the camera.

In another of the floats were two girls dressed in a white costume with fretwork, perhaps alluding to the Maya, and on the flag one can see the words "oro" and "mestiza". Unfortunately there is no description of this float in The Yucatan Magazine (see image 5).19

The Union sponsored one of the most admired floats, called "Pierrot and Colombina", which featured a Japanese tightrope walker and at his feet the beautiful Colombina, both characters from the Italian commedia dell'arte. According to The Yucatan Magazine, this carriage was the work of artist don Luis Améndola; Miss Aurora Sauri Zetina represented Colombina and Juan Cervera Reyes represented Pierrot: "He took part in the 'Union' bando last Saturday and was exceptionally applauded everywhere". Colombina's face is not visible in Schirp's image 6, only her silhouette, probably because it was taken against the light; she wears a puffy skirt and an umbrella. It is possible that Schirp, more than the impressive Colombina, was interested in the man leading the horses and the bare foot that contrasted with the color of the ground.20

Also seen in image 6 is the Peón Contreras Theater carriage (inaugurated in 1908) in honor of the poet and playwright of the same name, which represents a movie theater. In the upper frame are written the words "Empresa Cinematográfica"; in reality there were several of them and they were the ones that carried the films for projection in Mérida. On the stage were the ladies Rosita Briceño and María Peón Ongay; as spectators were the ladies Adriana Cardós, Edelvina Briceño and María Asencio, and as manipulators, the ladies María Trujeque and Eila Evangelina Férraez (The Yucatan MagazineFebruary 2, 1913).

Schirp took a photo of the cart of the Crasemann hardware store, known as El Candado, as the advertisement says, founded in 1869, whose owner was the German Félix Faller. On the cart were elegantly dressed and carrying -according to the chronicle- the attributes of the job, the ladies María del Carmen López and Generosa Trujillo. A Mayan man dressed in "traditional" costume, barefoot, pulling the horses and behind him several people with their umbrellas.21

Daniel Fabre (1992: 98-102) notes on the Paris carnival that the sponsoring carriages of the large commercial stores first appeared at the beginning of the century. xxThis practice was extended to the other carnivals. Yucatán was no exception: the sponsoring cars of the Craseman hardware store, the Gran Fábrica Yucateca de Chocolates, Casa Comercial El Gallito, Bicicletas Premier, Mundo Elegante, Nueva Droguería y Miscelánea de la calle 60 and the Oakland Chemical Company paraded. Likewise, the chronicle describes that several grotesque cars and carts participated, among the most striking were the one that carried a sign with the following title: "Tres bobos que se divierten a su modo", and the Fábrica de Cigarros la Paz, with a giant wimp.

Another float carried the celebrated Chanteclaire estudiantina, which means "rooster" in old French, which had made its debut at the Union society on the first day of the festivities and was made up of both men and women. Of all the floats that paraded it was the one that most evoked the old carnivals, in which the rooster had an important presence. Caro Baroja (2006: 77-94) has outlined the presence of this animal in the festivities. In the carnivals of some Spanish towns its presence was very common, either to hang them and then eat them, since roosters, for being lewd and representing lust, had to be sacrificed for Lent. He also notes that in general the rooster is "a kind of symbol of life, the expeller of death, of evil spirits, devils, witches, etc." (2006: 92). Nor was it a coincidence that they all dressed up as chanteclaireThe store was announcing that they had received several.22

The chariot of the Chanteclaire orchestra represents the most traditional and symbolic of the carnival as they are all dressed as roosters. In image 9, two of the members of the orchestra are better observed and again the person dressed in white with a striped apron (probably the waiter) looks at the camera in a gesture unconvinced to do so.23

On Saturday, February 1, around 8:30 p.m., people gathered again on the "profusely illuminated" 59th Street, to begin the battle of flowers, confetti and streamers of the Liceo de Mérida. Afterwards, each society hosted lavish parties in their halls. Paz y Union's is described as follows: "In the elegant halls of this popular and nice working class society, decorated with simplicity, but with a splurge of good taste, the attendance was also very numerous" (La Revista de YucatánSunday, February 2, 1913: 9).

On Sunday morning, the Union's flower battle was held on 64th Street; the event lasted from 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. with the same floats and bands as the previous day. The Union itself invited the creator of the "Pierrot and Colombina" float and its members to a lunch-champagne to congratulate them. So great was the success of this float that it was also invited to its battle of flowers that took place on Monday morning, the 3rd, at the Lyceum on 62nd Street. On Monday afternoon, some 500 children also paraded in the halls of the Union during the children's party.

An interesting fact is that the groups of "Xtoles", "negritos", "cintas", "palitos" and "murguistas" went from house to house performing their dances. Rosado Vega (1947: 98) indicates that "these comparsas whether or not they wore masks or masks; they did wear the most picturesque costumes, especially the mestizo, with zarandejas and exotic ornaments". In the afternoon, as had been the custom since long ago, the evening parades were reduced to a long parade of cars and the traditional five night dances. It is worth mentioning that cars could be rented: an advertisement indicated that renting a car cost eighty pesos for four days; as an example and to compare the price, a load of corn (almost one hundred kilos) cost three pesos.24 Miguel Güémez (2021) mentions that in the Motul Mayan Calepino, a dictionary written in colonial times, mentions a pre-Hispanic dance called the ix-tooli, which passed into Spanish as X'toles, "baile de los indios moharraches" (dance of the moharrache Indians); that is, of those who disguise themselves, and it was only there that the inversion of men dressed as women took place. Today, in the carnivals of other municipalities of Yucatán there are still X'toles troupes; those of Mérida have disappeared. However, no photographer photographed them this year, 1913.

A peculiar fact is the courtesy visit that some members of the Union paid to the popular societies Paz y Unión and Recreativa Popular to thank them for their support during the carnival. This gesture clearly exemplifies the cordial relations, as well as the limits that existed between them. There is a boundary that separates one from the other; although we do not see it, we know it exists.

It is noteworthy that The Yucatan Magazine he described, on the one hand, the meetings of the Union and the Lyceums and, on the other hand, "the popular societies". The former were described as "exquisite" and "exceptionally attended by the most elegant of our society", and a "splendid and delicate" "ambigú" was served. Of the "two popular and nice workers' societies" he mentioned that they had paraded "the most beautiful and beautiful mestizas of Mérida".

Among them were La Murga Criolla, the State Music Band, the Chanteclair student bands (already mentioned), that of the Union and the Murguistas, the orchestra of Maestro Mangas, the Military Band of the 16th Federal Battalion led by Geronimo Flores, the band of Everardo Concha, as well as the orchestra of Agustin Pons Capetillo. Good music was part of the atmosphere. One of these groups paraded without our being able to identify it.25

Given the competition between the high schools, there were two flower battles, one for the 62nd and the other for the 59th. On Tuesday, the last day of festivities, it was the turn of the flower battle of the Liceo de Mérida de la 62, the appointment was at eight o'clock in the morning. The chronicle of The Merida Magazine It is not wasteful, since it mentions that it was very well attended "by people of all social classes", 147 carts and 21 automobiles paraded "by elegant ladies of our society" (see image 11).26 At the doors of the Liceo, the Military Band of the 16th Federal Battalion under the command of Don Gerónimo Flores was present; inside the building, a comparsa and a concert of the murguistas criollos (Creole murguistas) were installed. We know the names of the board of directors: Don Fernando Cervera García Rejón, Don Federico Escalante, Don Perfecto Villamil Castillo, Don Elías Espinosa and Don Don Donaciano Ponce, who with a "display of gallantry" offered the ladies a "succulent lunchice-cold beer and champagne". These are not just names, they are surnames known and recognized by the local society.

Afterwards, all the guests moved to the Casa Quinta O'Horán, owned by Don Eulalio Casares, alias Don Boxol, where a picnic was held, "a Yucatecan style lunch sprinkled with fine wines". The peculiarity was that all the people who gathered outside the quinta to watch were also served lunch -although, of course, outside-. This note refers me to Roberto DaMatta's (2023) analysis of spaces and divisions by sex and age, to which we can add here the variable of social category, just as during the carnival: the poor participated, but outside. The author (2023: 15) mentions that the house has its street spaces, which act as a bridge between inside and outside, a brief wink of union between the two worlds.

As was customary, the party concluded with a dance in the halls of the Liceo. At nine o'clock in the evening, the traditional masquerade of the "Burial of Juan Carnival" started from the 59th Street Lyceum; the event was accompanied by jokes of all colors, responsos and a charanga. It was the end of the cycle.

We are facing a carnival of elites, in which the order of society is reproduced as it is, with its enormous social differences that are maintained at all times between the three superior societies and the two "inferior" ones. In this carnival there is no inversion or, at least, the photos do not show them to us; although the X'toles are mentioned, we do not know exactly who they were. There were no men dressed as women or Mayas dressed as "whites", nor vice versa, everyone occupied their corresponding place.

Several photos of the public show only men or boys, who by their clothing can be inferred to belong to different social levels. Women were also in attendance, although the photos hardly show them. In image 12 we can see the back of a float passing through one of the historical arches of Mérida, where we can see a huge bottle fixed on whose label we can make out the letters cb (perhaps Carta Blanca). In the lower right, three assistants can be seen: two ladies seated in white dresses and a little boy in his wooden chair.27

These days of joy would be followed by complicated political days because, without a doubt, the event that most affected Yucatan, and Mexico in general, was the tragic decade, the military coup against Francisco I. Madero and José María Pino Suárez that took place from February 9 to 18, 1913 and that would end with his death on the 22nd. Far away were those days of 1911 when they campaigned in Yucatan, boasting of their political strength.

Final comments

The year 1913 was unique and marked by violence and political instability in Mexico; however, in Yucatán, one of the most prosperous places in the world at that time, a German named Wilhem Schirp left us his legacy of various events, places, people and houses, which he considered of value. Thanks to him and the zeal of his family, today we have a visual idea of what Yucatan was like in those times. For the same event there were different looks and Schirp's was that of the foreigner, who just that year decided to document with his photos such an important event in the life of the city and captured details that for the locals were so normal that they passed by. His photos were intended for his private use, a memory captured in his album, now turned into a place of memory, an evocation of places in Yucatan and events that, although documented by others for public use (La Revista de Yucatán and photographer Pedro Guerra), take on different meanings with other photographic looks and approaches, or at least that is what they wanted to show.

We start from the idea that the carnival of Mérida at the beginning of the century xx was an event organized by the elites to show the wealth of the city, with a popular vocation, having normalized the presence of floats of "mestizas", which was reaffirmed over the years. Nowadays there is a specific day to show off the "ternos" called "regional Monday". However, Schirp's foreign gaze was able to capture very well in a few photographs the enormous contradiction that Yucatecan society lived in the midst of so much luxury and exuberance: the other population on which the burden fell, the Mayans, the waiters, all the support staff, who wore shoes and who did not, who were the protagonists and who only watched. The social differences were there, living shoulder to shoulder.

The carnival is also an event of collective memory because there will be no Meridian who does not have an interpretation around it. It is also a marker of the historical era, for in 1913 the elite were eager to show off their wealth: cars, costumes and beautiful women paraded through the streets in the hands of a few, while many others could only watch.

The Carnival of Mérida at some point began to grow, as the route was extended to Paseo de Montejo, a paradigmatic avenue of the city and also a sample of the ostentation and wealth of the time of henequen. However, in 2014 the new commercial and business elite, unlike the old, disdained the carnestolendas and moved the carnival to the outskirts of Mérida, where it acquired a totally popular character, far removed from the aspirations displayed by society a hundred years earlier.

Annex

Bibliography

Araujo Moura, Milton (2009). “A fotografía numa pesquisa sobre a história do Carnaval de Salvador”, Dominios da Imagem, Londrina, v. iii, núm. 5, noviembre, pp. 109-122.

Betancourt Pérez, Antonio y José Luis Sierra Villarreal (1989). Yucatán, una historia compartida. México: sep/Instituto Mora/Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1998). La distinción. Criterios y bases sociales del gusto. Ma. del Carmen Ruiz de Elvira (trad.). Madrid: Taurus.

Canto Mayén, Emiliano (2016). “Guía para el estudio de la colección digital Schirp (1893-1998)”, manuscrito. Ciudad de México. Recuperado de: (99+) Guía para el estudio de la colección digital Schirp.

Caro Baroja, Julio (2006). El carnaval: análisis histórico-cultural. Madrid: Alianza.

Concha Vargas, Waldemaro, José Humberto Fuentes Gómez y Diana María Magnolia Rosado Lugo (2010). Fotógrafos, imágenes y sociedad en Yucatán: 1841-1900. Mérida: Ediciones de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.

DaMatta, Roberto (2023). “Espacio. Casa, calle y otro mundo: el caso de Brasil”, Papeles del ceic, núm. 2.

Domínguez, Marisol (2017). “El paisaje social”, en José Antonio Rodríguez y Alberto Tovalín Ahumada. Fotografía Artística Guerra. Yucatán, México. México: Cámara de Diputados, lxiii Legislatura/Fototeca Pedro Guerra, pp. 253-267.

Duran-Merk, Alma (2015a). “Imaginando el progreso: la empresa eléctrica Siemens & Halske en Mérida, Yucatán, México”, Istmo. Revista Virtual de Estudios Literarios y Culturales Centroamericanos, núms. 27-28.

— (2015b). In Our Sphere of Life. Dimensions of Social Incorporation in a Stratified Society. The Case of the German-Speaking Immigrants in Yucatan and their Descendants, 1876-1914. Madrid: Iberoamericana/Vervuert.

Eco, Umberto (1989). “Los marcos de la libertad cómica”, en Umberto Eco, V. Ivanov y Mónica Rector (eds.). Carnaval. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Fabre, Daniel (1992). Carnaval ou la fête à l’envers. París: Gallimard.

Güémez, Miguel (12 de octubre de 2021). “De la danza ritual a la vaquería (y ii)”, Novedades Yucatán. https://sipse.com/novedades-yucatan/opinion/columna-miguel-guemez-pineda-yucatequismos-410454.html#google_vignette

Kossoy, Boris (2014). Lo efímero y lo perpetuo en la imagen fotográfica. Luis Parés (trad.). Madrid: Cátedra.

Halbwachs, Maurice (2004). La memoria colectiva. Inés Sancho-Arroyo (trad.). Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel (1994). El carnaval de Romans: De la candelaria al miércoles de ceniza, 1579-1580. Ana García Bergua (trad.). México: Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora.

Martín Briceño, Enrique (2014). “Yo bailé con don Porfirio: sociedades coreográficas y luchas simbólicas en Mérida, 1876-1916”, en Enrique Martín Briceño. Allí canta el ave. Ensayos sobre música yucateca. Mérida: Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán/Secretaría de la Cultura y las Artes/Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, pp. 84-107.

Millet Cámara, Luis y Ella F. Quintal (1994). “Traje regional e identidad”, inj. Semilla de Maíz, vol. 8, pp. 25-34.

Miranda Ojeda, Pedro (2004). Diversiones públicas y privadas. Cambios y permanencias lúdicas en la ciudad de Mérida, Yucatán, 1822-1910. Hannover: Verlag für Ethnologie (Estudios Mesoamericanos, serie Tesis 2).

Mraz, John, (2007). “¿Fotohistoria o historia gráfica? El pasado mexicano en fotografía”, Cuicuilco, vol. 14 (41), septiembre-diciembre, pp. 11-41.

Moriconi, Ubaldo (1902). Da Genova ai deserto dei mayas, Ricordi d’un viaggio commerciale. Bérgamo: Istituto d’Arti Grafiche.

Newhall, Beaumont (2002). Historia de la fotografía. Homero Alsina Thevenet (trad.). Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

Paz Ávila, Lilian (s.f). “La moda europea y su influencia sobre el terno yucateco durante el siglo xix”, Yucatán, identidad y cultura maya https://www.mayas.uady.mx/articulos/terno.html#_ftnref3

Peniche, Piedad (2010). La historia secreta de la hacienda henequenera de Yucatán: deudas, migración y resistencia maya (1879-1915). Mérida: Instituto de Cultura de Yucatán.

Perigny, Maurice de (2015). En courant le monde (1901-1906). Introducción y notas Albert-André Genel. París: Ginkgo Éditeur, pp. 127-131.

Pratt, Joan (1993). “El carnaval y sus rituales: algunas lecturas antropológicas”, Temas de Antropología Aragonesa, núm. 4, pp. 278-296.

Ramírez Aznar, Luis (2006). “De cómo se hizo cine en Yucatán”, Revista de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, núm. 243, pp. 56-67.

Reyes Domínguez, Guadalupe (2003). Carnaval en Mérida. Fiesta, espectáculo y ritual. Mérida: inah/uady.

Rodríguez, José Antonio y Alberto Tovalín Ahumada (2017). Fotografía Artística Guerra. Yucatán, México. México: Cámara de Diputados, lxiii Legislatura/Fototeca Pedro Guerra.

Rosado Vega, Luis (1947). “Los carnavales”, en Lo que ya pasó y aún vive. Entraña yucateca. México: Cultura, pp. 89-120.

Salazar, Álvaro (1913). Yucatán. Artículos amenos acerca de su historia, leyendas, usos y costumbres, evolución social, etc. Mérida: s.e.

San Juan, Héctor (09 de julio 2022). “Entrevista a Gil-Manuel Hernández en torno al libro La gran Fira de Valencia (1871-2021)”, La Vanguardia, La historia de la gran fiesta que ideó la burguesía para presumir y mostrar la Valencia moderna (lavanguardia.com)

Shirp y Milke, Juan Edwin Arthur (2017). Memorias de un sancosmeco. Selección, revisión de textos y comentarios Alma Durán-Merk y Laura Machuca. Mérida: Compañía Editorial de la Península.

Uresti, Silvestre (2022). “Carnaval de Mérida, Yucatán, 1850-1940. Una tradición que lucha contra su elitismo”, Península, vol. xvii, núm. 1, enero-junio, pp. 9-33.

Archives and libraries

Archivo General de la Nación, México

Ayuntamiento de Mérida

Biblioteca de la Universidad de Augsburgo (bua)

Colección fotográfica Schirp-Milke (cfsm)

Centro de Investigación Histórica y Literaria de Yucatán (caihly)

Actas del Cabildo de Mérida

La Revista de Yucatán. Mérida: 1-6 de febrero de 1913.

Filmography

Carnavales y comparsas tradicionales de Yucatán (2 de enero de 2011). Carnavales y comparsas tradicionales de Yucatán. Compañía de Danza Folclórica Kaambal. Recuperado de: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ncXuou8Kfoo, consultado el 2 de febrero de 2025.

Laura Machuca Gallegos holds a bachelor's and master's degree in History from the School of Philosophy and Letters of the Universidad de Chile. unam D. in Latin American Studies, specializing in History, from the University of Toulouse le Mirail, France. She is a tenured research professor at the ciesasHe lives in the Unidad Peninsular, Mérida, Yucatán, where he resides. His areas of interest have been colonial and 20th century history. xix for the regions of Oaxaca and Yucatán, for which he has published several articles and books, among them Power and management in the Mérida City Council, 1785-1835 (2017) y The subdelegates in Yucatán. Spheres of political action and social aspirations in the intendancy, 1786-1821. (2023). Member of the National System of Researchers level ii.

Image 4. bua-cfsmTwo pictures of floats in Merida's 1913 Carnival", Schirp-01-035. http://digital.bib-bvb.de/webclient/DeliveryManager?custom_att_2=simple_viewer&pid=13305803

See in the "Annex" Guerra's image to see Colombina in all her splendor. We have another photograph taken by Pedro Guerra, in which more details of the float and Colombina can be seen (La Revista de YucatánThursday, February 6, 1913).