The Documentary as Witness: Dance Memories in the Costa Chica (part 1)

- Rosa Claudia Lora Krstulovic

- ― see biodata

The Documentary as Witness: Dance Memories in the Costa Chica (part 1)

Receipt: October 3, 2024

Acceptance: December 10, 2024

Abstract

The ethnographic documentary has been one of the ways of recording and showing the diverse Afro-Mexican dances of the Costa Chica, the article argues that this audiovisual genre can also be used as a way of investigating dance memory. The text makes a first analysis of the documentaries produced on the dances of this region and presents part of the process of making the documentary feature film Maybe, where memory dancesdirected by the author, whose primary interest is to contribute to the collective memories of a people.

Keywords: Afroméxico, dance, documentary film, memory

the documentary as witness: dance memories on the costa chica (part 1)

Ethnographic film has been one of the ways to document and showcase the diverse Afro-Mexican dances of the Costa Chica region. This article shows how this audiovisual genre can also serve as a method to investigate dance memory as it presents the documentary films dedicated to the dances of this region. It then turns to a feature-length documentary directed by the author, Maybe, where memory danceswhich aims to contribute to the collective memory of a community.

Keywords: documentary, dance, memory, afroméxico, black Mexico.

In memory of Don Hermelindo and Don Bruno

Introduction

What ethnographic documentaries have been produced on the dances of the Costa Chica in Mexico? How can their analysis contribute to the study of the memories of the traditional dances of the region? How was the making of a documentary that dialogues with the dance memories of a people conceived? These are the questions that guide the objectives of this text.

From the beginning of my career as an ethnologist I decided to dedicate myself to the study of Afro-American dances. This happened after watching a documentary in an Anthropology of Dance class that told fragments of the history and present of the Afro-Mexican population through dances and music of the region. An image stuck in my memory that struck me: the devil dancers dance on the shore of the beach and then completely submerge, could this be a healing dance or what did this image represent? I asked myself that question repeatedly, until, being in the Costa Chica, I discovered that this part had been the director's invention, because traditionally the dance did not take place in that way.

That experience has raised questions and reflections for years and today I realize that it marked my career in at least two ways: on the one hand, I began to question myself about the delicacy of representing the "other"; I realized the power that filmmakers and anthropologists have to produce imaginaries about the cultures we investigate, and how subjectivity and fiction in the documentary play an important role in the representation of diverse realities. A vast literature has been written on this topic (Nichols, 1991, 1997; MacDougall, 1998).

On the other hand, these images were so powerful that they took me to the place where they had emerged, to the Costa Chica; there a totally unknown world was revealed to me, invisible to most Mexicans at that time (2000). From that moment on, I dedicated myself for years to the research and recording of dances in Afro-America (Mexico, Venezuela, Panama, Cuba, Brazil, Peru), which always generated questions like the ones I asked myself that day, related to the audiovisual and the representation of social reality: the limits of documentary and fiction; the interdisciplinary languages; the memories that these recordings keep with them (Lora 2024) and, in this sense, the documentary as a way to investigate cultural memories, the central theme of this writing.

As we are in the second International Decade for People of African Descent -decreed by the United Nations General Assembly-, we are in the midst of the second International Decade for People of African Descent. unesco In 2024- and only a few years after the Afro-Mexican population has obtained constitutional recognition (2019), several researches and films related to this topic have emerged. In addition to my interest in studying these productions and joining the effort to make visible the artistic expressions of Afro-Mexican peoples, this research has the intention of delving into the dance memories of the people of El Quizá. For this reason I developed my first feature-length documentary -still in post-production-, whose central theme is the new group of Danza de Diablos in El Quizá, Guerrero.

Since 2019, the young people of El Quizá have been trying to consolidate a group against all odds, or rather, against pandemics and hurricanes. For having been a person who recorded this town, its rituals and loved ones for more than 20 years (with long interruptions), the community allowed me to make a second documentary on the Danza de los Diablos. This work has aimed to collaborate with the revitalization of the dance and the memories related to it. In this sense, through audiovisual ethnographic research, I accompanied and recorded the dancers in the search for their own representation through the reactivation of their dance and musical repertoires. With the help of a work team, audiovisual material recorded between 2020 and 2023 was generated, in addition to the recordings that had already been made between 2000 and 2008, with which a large part of the documentary was edited. The game of the Diablos: celebration of the dead in the Costa Chica of Guerrero and Oaxaca.

To begin this journey, I consider it necessary to problematize the term "ethnographic documentary", to later analyze the way in which anthropologists and filmmakers have contributed to generate notions or ideas about Afro-descendant dances through the recording and circulation of such audiovisual products. On the other hand, the process of a documentary project of our own is presented, which seeks to contribute to the struggle of young people to revitalize a dance that was thought to be lost.

The ethnographic documentary and the recording of the dance repertoire

Broadly speaking, the term ethnographic documentary refers to a form of audiovisual production. non-fiction (Grierson, 1932) conducted from ethnography, a social research method and approach used to study and describe social phenomena (Guber, 2011).

José da Silva Ribeiro states that

In the expression ethnographic film or ethnographic film, the word ethnographic has two distinct connotations. The first is that of the subject matter it deals with-ethnos, θνoς, people, nation; graphein, γρφειν, writing, drawing, representation. The ethnographic filme would be "the representation of a people through a filme" (Weinburger, 1994). This is the scope of the films Flaherty's Nanook of the North and the essays on ethnographic film by MacDougall (1975, 1978) and Timothy Asch, John Marshall, analyses by filmmakers who photographed or filmed exotic cultures. The second connotation of the term ethnographic is that there is a specific disciplinary framing within which the film is or was made - Ethnography, Ethnology, Anthropology - (Da Silva, 2007: 9. Author's translation).

Although in its beginnings anthropology focused on the investigation of foreign societies, nowadays, and for decades, it is a method that can be used both to study the society to which the researcher belongs and to approach any culture other than his/her own. One of its main characteristics is "participant observation", a term coined by the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski (1922), which refers to the researcher assuming an active role in the tasks of the society he/she is studying, observing every detail and learning from his/her interlocutors. Ethnography is, therefore, a practice that, although transformed and adapted to the particular context, time and situation, remains the research method that characterizes anthropology.

The term ethnographic documentary arises then as a way of defining audiovisuals made by ethnologists or filmmakers who use ethnography to record and describe the culture under study. More recent authors, such as the visual anthropologist Antonio Zirión, propose a somewhat different meaning of the term ethnographic and therefore of ethnographic cinema:

...it seems to us more appropriate to characterize it first of all as a form of experience, a disposition, an attitude, a way of looking, a type of sensitivity that implies a constant estrangement, amazement, curiosity and interest in the face of the verification of identity, otherness and cultural diversity (Zirión, 2015: 53).

This definition, which highlights elements related to the form of interaction between the one who wants to know and the one who allows this dialogue to happen, whether anthropologist or not, allows us to understand ethnography from a different perspective. For Antonio Zirión, ethnographic cinema "is that which propitiates an intercultural dialogue, which provokes an ethnographic experience, an interaction or transaction in which both parties are transformed" (Zirión, 2015).

Some researchers have suggested the term anthropological documentary to refer to a social cinema, concerned, in its narrative, not only with the descriptive but also with an analytical and propositional approach.

The anthropologist Karla Paniagua in her book Documentary as a melting pot (2007) attributes to ethnographic cinema an association with exotic or primitive cultures, which would leave out the perspective of urban productions and those views of the researcher on his own culture. He opts for the term "anthropological documentary", to which he attributes certain characteristics:

- It focuses its arguments on the cultural life of various human groups.

- It is articulated on the basis of concrete research premises.

- It presupposes a theory of culture and therefore an ideological sieve.

- It involves an ethical framework inherited from anthropology, which considers the relevance of the informed consent of the participants (Paniagua, 2007: 32).

The debate that has developed around these terms is long and complex. My proposal in this paper is that, regardless of the name it adopts, and from the discipline or place we are talking about and/or filming, it is extremely necessary that constant problematization and not neglect the historical and current processes from a critical and committed point of view, because, as Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui says, the sociology of the image has to be problematized in its "unconscious colonialism/elitism" (Rivera Cusicanqui, 2018).

In this sense, the way in which the documentary has been used to record the corporeality of other cultures also has to be problematized, questioning who, for what and for whom the work is done and, on the other hand, being aware that the audiovisual material we produce will become an audiovisual reference of the cultures portrayed.

People of African or African descent have historically been associated with the ability to dance rhythmically, to the point of being a completely naturalized idea. Phrases such as "rhythm is in their blood" are common to describe them. Colonial capitalist thinking has led to the idea that, genetically, this population is "made" or skilled in everything that has to do with labor and bodily actions, while at the same time calling into question their rational capacity. This representation of blackness is nourished by ideas of race that reverberate to this day and have been part of racist policies of conquest and domination.

Cinema in general has helped to reinforce these thoughts, reproducing dominant discourses. This can be seen most clearly in fiction films, in which black characters play the roles of servants, white people's workers, comedians or dancers. In documentaries, the colonial gaze is more difficult to observe; its value as a historical-cultural record, as well as for dissemination, can cloud the critical gaze towards these productions.

Dance and religion have been persistent ways of representing Africans or Afro-descendants in film and ethnographic photography. Dance and religion, cultural elements strongly repressed and used in the colony to discriminate and create evolutionary theories that place indigenous and enslaved Africans in the lowest link, are referents that, in the European mentality, differentiated their societies from the "other" primitive or savage ones.

It is undeniable that these productions contain a valuable ethnographic testimony, but, on the other hand, the reality they are intended to show is clearly influenced by the exoticizing Eurocentric gaze.

While it is important to present this issue, which is fundamental to understanding the historical representation of these cultures, it is clear that not all films are made in this way and that, especially in recent years, as a result of anti-racist, feminist and cultural demands, part of the population has become aware of the persistent colonial structures and has sought various ways to transform the dominant practices and discourses.

In the context of patrimonialization, recognition of Afro-descendence and the need for historical reparations, some researchers ask similar questions; one of the central axes revolves around how to contribute to the struggle for cultural memories and the dignification of Afro-Mexican and indigenous populations.

It may be that in Europe this stage began with the Cinema Vérité, proposed by Jean Rouch after having made his first documentaries. Having a more conscious vision and being in dialogue with researchers such as Edgar Morin, they propose a different way of representation, in which interaction and consensus with the protagonists becomes fundamental, stating that the ethnologist has to become a filmmaker because: "although his films are quite inferior to the work of professionals, they will have that irreplaceable quality of real and primary contact between the person who films and those who are filmed" (Rouch, 1995: 107). Another difference with respect to previous ethnographic cinema is that Rouch and Morin's cinema Verité showed its protagonists the filming of the shooting, sharing their impressions of it.

In Latin America, collaborative documentary has developed in different ways and under different names, transforming narratives and attempting to produce material with the participation of others. This poses challenges both to the social sciences and to cinema itself, as it breaks down ideas and proposes new ways of working, telling and investigating.

Documentaries on Afro-Mexican dances of the Costa Chica

Despite the fact that historically, and even today, the African, indigenous and Afro-indigenous cultures of the American continent have been stripped of many of their historical-cultural and territorial heritages, these cultures have resisted by conserving, reinventing and generating other forms of preserving their memory. Enrique Florescano refers to myths, images, rites, the solar and religious calendar, as well as oral tradition (Florescano, 1999). Performance researcher Diana Taylor, for her part, introduces the term repertoires corporeal as a counterpart of the archive (privileged by Western epistemologies). Repertoires would perpetuate a performative memory, anchored in the transmission of bodily practices (Taylor, 2017). In this sense, dance is one of the most representative repertoires, it is part of traditions that are fundamental pillars of their cultures, many of them identity emblems and forms of memory resistance.

This is the case of the Danza de los Diablos de la Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Guerrero, which today is an icon of Afro-Mexicanity, as researcher Itza Varela points out:

It is presented as an indelible mark of the black-Afro-Mexican identity and is one of the central elements of the cultural politics that sustains the practices of Mexican Afro-descendants and allows widening the paths of political mobilization (Varela, 2023: 2010).

As the people of the Costa Chica themselves affirm, it is a dance that represents the strength and resistance of the Afro-Mexican peoples. The way in which researchers, artists and, in general, the population interested in this subject have approached to study it and leave a record of its existence, has been through writing, photography and film, video and audio recordings.

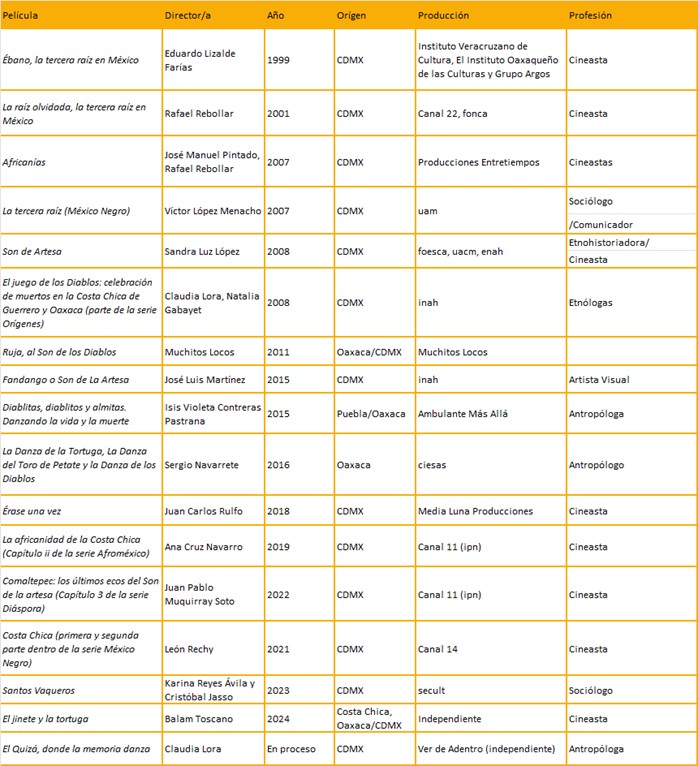

In Mexico, a large part of the documentaries made about the Costa Chica region incorporate its traditional dances as a way of evidencing the distinctive cultural characteristics of Afro-Mexicanity. The table I present here is a first systematization that contains 17 documentaries produced over 25 years (1999 to 2024). One thing that stands out is that most of these have been made by anthropologists and filmmakers; almost all of them directed by people from Mexico City, except for four, created in part or in whole from the state of Oaxaca. It can be observed that, of the 17 works, ten are directed by men and seven by women.

Another aspect to highlight is that there is a relatively continuous development in the production of documentaries on the subject of African descent in the region, ten of them are the result of governmental economic support (derived from cultural institutions and public television stations), six from independent producers and one from the best known documentary film festival in the country, Ambulante.

Ebony, the third root in Mexico (1999) is probably the first documentary made about the Costa Chica and Veracruz. It is narrated by a voice in off poetic mixed with a more educational approach, added to reflections of the interviewees (researchers, activists, dancers, etc.), who talk about historical, economic, geographic, ethnic, gastronomic and traditional medicine aspects. From this first work, the Danza de los Diablos is presented as an emblem of the Afro-Mexican dance tradition of the Costa Chica.

The forgotten root, the third root in Mexico (2001), by Rafael Rebollar, dedicates a large part to narrate the history of the African population in the country through the voices of Mexican and African researchers. The last part contains fragments of various dances that, he suggests, have African ancestry, the first to appear are the Danza del Toro and the Danza de los Diablos de la Costa Chica, focusing on one of the instruments called bote, alcuza or tigrera, which, it is affirmed, comes from Africa.

The movie Africanías (Rebollar, 2007) that I mentioned at the beginning of the text was the first to bring the national public closer to the dance traditions of the towns of the Costa Chica. Although the audiovisual productions directed by the author were avowedly documentary, they had tints of what today is known as docufiction. Africanías contains fictional scenes of traditional rituals, such as the shots of the Diablos dancers dancing on the beach, or the characters of the Danza de Conquista arriving on a boat. These have a great symbolic force that lingers in the memory of the viewers, as it happened with me.

In 2008, two short films were presented with two iconic dances of the Costa Chica as their central theme: Artesaby Sandra Luz López, and The game of the Diablos: celebration of the dead in the Costa Chica of Guerrero and Oaxaca, co-directed by myself and Natalia Gabayet. In the first one, López rescues the way in which the son de Artesa was danced and shows the work of reactivation of the dance carried out by some people from the community of El Ciruelo, highlighting the role of Doña Catalina Noyola Bruno, a legend of the genre, originally from San Nicolás Tolentino. A contribution to the legacy of women, their maintenance and reproduction of Afro-Mexican dances.

The second documentary is part of the series Origins (tv inah), and shows the characters of the Danza o game of the Diablos explaining their performance with the focus on the imaginary that the population has around the figure of the devil. In this way, it ceases to be a descriptive documentary, to dive into the subject of the imaginary and collective memories related to the devil, a very important figure for the black peoples of America. The series includes a voice in off which simulates the voice of the anthropologists, in which they explain aspects of the dance and ask questions about this expression. It is worth noting that both productions were made by three researchers trained at the same institution, the National School of Anthropology and History (Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia (enah).

In 2011, the video collective Muchitos Locos de Oaxaca and cdmx makes the documentary Ruja, to the Sound of the Devils in Lo de Soto and Chicometepec, Oaxaca, which shows aspects not previously addressed. This material constitutes a closer approach to the socioeconomic reality of the region and, for the first time, it assumes a group of women dancing the Danza de Diablos, vindicating that this is also their dance and that not only men can dance it.

In 2015, the Fandango or Son de la Artesaby the photographer José Luis Martínez, also produced by the inah and the crespial (unesco). A documentary that talks about the musical and dance history of the Artesa as a cultural heritage, emphasizing the risk of its disappearance and inviting to its recovery.

Little devils, little devils and little souls. Dancing life and death (2015) is a short film directed by anthropologist Isis Violeta Contreras Pastrana and produced by Ambulante, which presents the tradition of the Danza de los Diablos in a town in Guerrero, danced by a group of children, in which the context of violence, drug trafficking and insecurity in which children live is placed.

In 2016, ethnomusicologist Sergio Navarrete (ciesas) is carrying out a musical project in Llano Grande La Banda and as part of this project presents descriptive short films about the Danza de la Tortuga Danza, the Danza del Toro de Petate and the Danza de los Diablos in that community.

A feature film that stands out for having a different narrative is Once upon a timeby director Juan Carlos Rulfo (2018), is about a girl (the director's daughter) who discovers Mexican traditions through the Danza de los Voladores, in Veracruz, the Danza de los Diablos de la Costa Chica and the huapango of the Guanajuato highlands. A work that can raise diverse interpretations about the representation of Mexican identities. Although its circulation has been limited, it opens the possibility of reflecting on how childhood is placed as a space of discovery and intersection between different cultural traditions.

In recent years, some short documentaries or documentary series financed by state television channels have shown the Afro-Mexican character of the Costa Chica through its dances. The second chapter of the series Afroméxico of Channel 11 (2019), called The Africanness of the Costa Chica, directed by director Ana Cruz and produced by Susana Harp, it first locates the region, and then talks about the Danza de los Diablos de Chicometepec, the mural Freedom danceby Baltazar Castellanos, as well as the dance of Artesa del Ciruelo and the dance of the Toro de Ometepec. Likewise, the series México negro (2021), directed by León Rechy and produced by Canal 14, contains chapters dedicated to the Costa Chica, which includes the Danza de los Diablos, the Artesa and the Danza del Toro.

Comaltepec: the last echoes of the Son of Artesa (2022) is the third chapter in the series Diasporaproduced by Channel Eleven. Presented in black and white and hosted by artist Susana Harp. In its narrative, it uses exclusive interviews with two great ethnomusicologists, who explain diverse manifestations of dance and music of the Coast, not only of the Artesa, as the title refers. In the documentary we see and hear dancers of the Toro, Artesa and Diablos from various communities, as well as outstanding musicians, such as Efrén Mayrén, originally from the community of El Ciruelo, who speaks about his memories related to the Artesa festivities, and musicians from the Danza los Diablos de Comaltepec who comment on their participation and dance dynamics.

In 2023, the film Santos Vaqueros, by Karina Reyes Ávila and Cristóbal Jasso, is produced, showing the Danza de los Vaqueros or the Danza del Toro de Petate in La Estancia, Oaxaca, highlighting the relationship between dances, the Day of the Dead, social cohesion and identity.

Finally, the powerful short film The horseman and the turtle (2024), by Costa Rica's Balam Toscano, arrives with a fresh and innovative narrative in the form of a film essay. Through beautiful images of children and young dancers of El Ciruelo and the subjective voice of a teenage girl, the work reflects poetically on the place of men and women in the Danza del Toro (and in the community in general), placing cultural questioning and profound affirmations.

In all these audiovisual works, dance is an element that runs through them. Among them is also mine, Maybe, where memory dances, which, being an independent work, awaits a financing opportunity for its post-production.

It is interesting to see how the path of the documentary dedicated to the theme of the dances of the Costa Chica has been traced, certainly by filmmakers, but also by anthropologists, mostly women researchers interested in Afro-Mexican cultures.

On the other hand, with the exception of one, all the productions have been directed by non Afro-descendants, an issue that deserves a thorough investigation, because although at present, and increasingly, there are Afro-Mexican filmmakers, the themes they work on are others: contemporary arts, gender, migration, racism, territory, sports, etc. On the other hand, we must consider that the films are the result of a collective work and, therefore, they are often an intercultural creation. In this sense, the people of the communities or villages where they are filmed, in addition to being interviewed, also cooperate in production, organization, etc., aspects that should be further reflected upon and taken into account in the credits and retributions.

We also see that many of the productions are descriptive documentaries that explain, for a non-expert audience, the dynamics of the dances and music: characters, festivities, interactions, etcetera. This information is well known by the majority of the villagers, since the intention of these works is their dissemination in other Mexican and international territories.

On the other hand, there are aspects of utmost importance for the populations, such as the historical aspects that are described; these are often communicated by academic specialists and by specific people from the communities who have been in charge of researching, preserving and transmitting the knowledge of dance and music. The voices that narrate information about dance dynamics and traditional festive contexts are, for the most part, those that form or have formed part of the collective of dancers and the musicians that accompany them. In this sense, we can say that, independently of the narrative, these works keep community memories, although others are also generated, constructed with the production team.

In equal order of importance are the images and sounds of the dancers and musicians dancing and playing; although these scenes do not communicate with a spoken discourse, they do so with their dancing corporeality, with their steps, their playfulness, their movements from head to toe, their spatial and temporal displacement, their masks and costumes, and so on. This memory is the one that has interested me the most and to which I have dedicated my research: the body repertoires, through which a large part of the collective memory of the black and indigenous peoples in Mexico and the continent has been transmitted. It is also this memory that the dancers investigate, turning to the oldest dancers. Today, one way to investigate their dances are videos, used to remember and repeat movements, listen to dance and music masters who have passed away, relive spaces, games, sounds, etcetera.

Although it would be necessary to mention many other narrative aspects, the elements presented here give us an idea of the content of these audiovisuals, which are significant for the Afro-Mexican populations where the audiovisual material is recorded. The following anecdote shows this sense of belonging of the communities: on one occasion I interviewed a group of Diablos dancers, with whom I went to the Cineteca to see Juan Rulfo's documentary, and they confessed to me that, beyond the narrative or the stories, what had most caught their attention were the places and the people who recreated the material, watching the film made them long for their land, their culture and "their people".

Back to the origin: the ethnographic documentary as a remembrance process in El Quizá, Guerrero

The following lines are dedicated to develop the process of making a documentary that integrates old and new recordings of dance in the two periods worked, my beginning as an anthropologist and the last years of postdoctoral work (2000-2008 and 2020-2024).

The purpose is to present the process of my first feature film and the attempt to work collaboratively with people from the community, as well as with a film crew, something that had not happened before in the places where I have worked on long term research, because I always filmed alone and with very basic equipment. Previously (2001-2008) I had recorded with academic intentions and later for the opportunity to disseminate this dance expression of the Costa Chica. In this new project there is a conscious idea that the film is for the community of El Quizá. A work that contains materials recorded 20 years ago, mixed with new ones, recorded by professionals in the cinematographic area.

This feature film is designed to contribute to the collective memory of a community that I came to 25 years ago, with an innocence alien to the power of image and sound, but that today acquires a crucial urgency as a place of memories for old and new generations.

The making of the documentary that I recently renamed as Maybe, where memory dancesrecorded between 2020 and 2023 and currently awaiting the next stage of post-production, has represented, in the first instance, a long ethnographic and artistic process. The big difference with previous recordings in El Quizá and other Afro-American villages was that this time the production was carried out with a small team of filmmakers who accompanied me intermittently: photographer Venancio Lopez (Tlaxcala/cdmx) and sound recordist Clemen Villamizar (Acapulco/cdmx), granddaughter of one of the founders of El Quizá.

Part of the filming was done in pandemic conditions, with the proper sanitary protections, with no budget for the project, but with a lot of enthusiasm on the part of the team. From the first moment I asked permission to the community and especially to the group of young people and children Diablos Quizadeños Nueva Generación; I asked them if they were interested in making a documentary about this stage of reactivation of their dance, and they accepted excitedly.

Talking after such a long time with people I already knew allowed me to do fieldwork quite comfortably and calmly. It made me understand some issues related to the recovery of dance and the factors that crucially determined this process to happen. In the first year, I recorded with a very short set-up.

I wanted to do a more autoethnographic work about what it meant to me to return to the Costa Chica after more than ten years. This is how I expressed it to Venancio (the photographer of the project), who recorded the car ride, my arrival, the welcoming hugs and all those emotional actions that arose in the reunions with each of the people I met.

I found myself in the particular situation that Mr. Bruno Morgan, a musician with the flute, o harmonica, who organized the dance year after year for decades, was no longer alive. His departure meant that dancing had ceased for many years in the village. So I was interested in what the absence of don Bruno had meant and how a new generation of dancers had organized in the midst of a pandemic. I conducted interviews with some people and decided to return, more prepared, the next year. In the second part of the filming I was accompanied by filmmaker Clemen Villamizar, who was in charge of the sound. On camera, Venancio López, a fellow graduate student of documentary filmmaking at the unam. At that time the only thing I knew was that the central thread of the documentary would be Don Bruno, but that the focus would be on the new generations of "devils".

Portraying the absence of don Bruno

How to portray don Bruno if he was no longer there? That question haunted my mind the second year of recording, accompanied by a feeling of nostalgia.

Most of the time I had gone to record without a set list, capturing what seemed interesting to me, organizing the interviews in a short period of time. My recordings followed more the anthropological methodology than the film methodology, because I didn't plan so much what I wanted to highlight in visual and sound terms. This time I did arrive with clearer ideas, taking into account what I had learned in film classes at the enac (unam); the script was not finalized, but the production team demanded it urgently, so I finished it while I was there. I knew that the most important thing was to talk about don Bruno with poetic images and sounds that would evoke his presence and absence at the same time, so that the community would understand who I was going to talk about when they saw or heard them. Shots were taken and audios were recorded related to this character; his house, a harmonica, sounds and images that those of us who knew him could locate. We also recorded people who knew him and who told us about him.

And since the nature of Day of the Dead is poetic, unexpected things began to happen, such as his family starting to revitalize previously empty spaces, placing an altar for him on the Day of the Dead, painting the house where he lived, and so on. The Diablos group planned to dance in front of the altar of her house, a highly beautiful and memorable moment. In this way, between his family, the community and those of us who were recording, we generated an atmosphere in which his presence was felt and at the same time we created memories for posterity that were engraved in our memories, but also in the audiovisual memory; the cameras and microphones were full of don Bruno.

These stored memories of sounds and images were later chosen and edited in terms of a narrative of memory, in the development of which the participation of filmmaker Julián Sacristán was essential. The organization and editing of this material was fundamental to generate the appropriate atmosphere. Choosing and searching for the moments that were recorded so many years ago with don Bruno represented, in its first phase, an arduous work of digitalization of the cassettes recorded in hi8, and in a second phase, of selection of the material in which we found several takes used in the film. Putting together a puzzle with such a beloved and remembered person in the town, who was also a musician, helped to work the project through sound as a metaphor that would bring us closer to him in each sequence.

The sound became a key piece to reconstruct the presence of don Bruno. It was through the melodic breath of his flute -as the harmonica is called in Costa Chica-, cheerful by nature but tinged with melancholy in his absence, we returned to inhabit his empty house. In some scenes, that sound recorded more than twenty years ago, when he enthusiastically accompanied the Diablos dancers, is interwoven with the images, filling the present silence with echoes of the past.

Although during the filming days we were able to record, together with sound recordist Clemen Villamizar, each of the musicians with their instruments, it was especially moving to record don Hermelindo, who played the boat with a dedication and energy that sustained the collective rhythm. His death last year made the edition of this documentary acquire another layer of nostalgia: not only for don Bruno, but also for don Hermelindo. What began as a record also became a farewell, sound memories that today remain sustained by the memory of a community that does not forget.

The sound edition has been one of the most complex stages: between the emotion that comes with the loss and the lack of resources to work with a sound designer, this dimension is still a pending task. The sound, as an invisible thread of memory, is still waiting to be woven with more time and care, to do justice to those who, with their music, have kept alive the Danza de los Diablos de El Quizá.

Recording on Day of the Dead

Recording on the Day of the Dead, during the pandemic period, was an unusual experience. In every town in the country it was forbidden to enter the cemeteries, and El Quizá was no exception:

- "We cannot go to the cemetery, they are not going to let us, they are going to close the cemeteries, because many people have died, they say, but not here in El Quizá."

- "But the pantheon has no door (laughs). How can we not dance in the pantheon for the dead?" (Danzantes de Diablos, El Quizá, conversation with the author, 2020).

Finally, the community decided to dance every day of Todos Santos, including November 2, the traditional day for dancing in the cemetery.

Don Hermelindo, the oldest musician, who played the boat and who sadly passed away in September 2024, recalled in those days: "the devil never went to the cross, because the devil is afraid of him, but not now, now they go to the cemetery where there are many crosses, look, and now they go to the cemetery" (Don Hermelindo, conversation with the author, 2020).

The remembrances of the older people were mixed with the determination of the young dancers. These two parts, always in dialogue and tension, were attempted to be placed in the documentary to show the complexities involved in the revitalization of a traditional dance such as this, for which interviews or open conversations were recorded, but also the dance in the pantheon in front of the crosses.

The two previous days a lady held an event for the third anniversary of the death of her son, who had also been a Diablos dancer in life. That day, T-shirts with the photograph of the young man, whom everyone remembered, were handed out, tamales and barbacoa were eaten, and there was a lot of dancing in front of the altar. Few people were able to see the dance in front of the altar, the cameraman and I were fortunate to witness such an emotional performance of the dancers who danced and sang verses to the deceased.

Other places where it was danced were in the homes of people who had just arrived "from the north" (United States), because they wanted it to be danced on their altars, since they or their deceased liked it.

The second year I was invited to be a mayordoma, a difficult decision because there was no such tradition in the town, although there was in the community of Lo de Soto, the town where most of the quizadeños/as come from. I accepted after understanding that they saw it as a form of collaboration so that the children in the group would acquire more responsibility. I then had to make tamales and buy drinks for the first Day of the Dead and take on the responsibility of giving them flavored water every day of the rehearsals.

That same year the Festival Raíces, from Coatepec, Veracruz, asked me to contact a group of Devil Dancers from the Coast, to dance in their festival, on that occasion presented in a virtual format. Without thinking about it, I told the members of the Grupo de Diablos de El Quizá Nueva Generación, who accepted. At that time my recording team helped in the recording and editing of the material. It is worth mentioning that the money received was paid directly to the dancers and a small percentage went to the photographer and editor of the material.

As part of the autoethnographic work, I felt it was important to record the experience of being a butler, so in the film you will see shots of me preparing tamales, asking why they chose me, and I also participate in the game of the face dance. blackened, accompanying the Tenango and the Minga; the latter is a traditional practice of the Devils of the region that had not been carried out for some years, but this year they wanted to revitalize the practice, which consists of chasing the participating public to paint their faces with smut.

The third year, in 2022, I returned alone, although a social psychologist colleague attended one of the days. That year it was my turn to support the mayordomo, who was don Luis Morgan, son of the late Bruno Morgan. I made the flavored water for the Diablos during the rehearsals and on the days of Todos Santos. That year was also very emotional, because the family of don Bruno arrived in town after many years and made a collective party with live music in honor of his father.

Recording memory locations

The places recorded were first and foremost places of memory, places that reminded everyone of people, situations and moments in which there was a strong presence of the Devils. Don Bruno's house, the cemetery, other houses where people lived who are no longer here. When I reviewed the material I realized that I not only portrayed the absence of don Bruno, I also portrayed the absence left by death. Why? Because the context of the Danza de los Diablos is that; the Days of the Dead are days to remember the absence of loved ones. It is not by chance that the representative dance of this region is the Danza de los Diablos, a dance linked to Africa, and which is danced on the Day of the Dead to remember the ancestors and the people who are no longer with us. Don Hermelindo always remembers the origin of the dance in those days of evocations, in 2020 he mentioned the following: "They say that this dance came from the area around the Lighthouse, it is not Oaxaca, it is Guerrero, and there that ship sank and some black people came out and that is how they danced this dance, and then it started in Cuajinicuilapa, it was a group". The following year he mentioned something similar again: "That dance is African, those devils, a ship sank in Punta Maldonado, and some black Africans came out, that's how it was" (don Hermelindo, conversation with the author, 2021).

In the collective memory, the dance and the people of the Costa Chica come from Africa, and to explain it symbolically, the nearby places with the presence of the sea are located, because, in the imaginary, that is where the ships from where they came from ran aground. As researcher Laura A. Lewis mentions: "At different levels, the ships and the saints signify the memories of the community and the feelings of belonging" (Lewis, 2020: 81).

The oral histories told by Hermelindo, and also told by don Bruno 20 years ago, which refer to the founding myth of the dance, made us go to Punta Maldonado, better known as El Faro, and record this place of memory, recording the vast sea through which the enslaved Africans arrived to what is today the Costa Chica of Guerrero and Oaxaca. Historian Pierre Nora proposed, in the 1980s, the term places of memory, relating them to the French collective memory and its relationship with history. He defined it as "the set of places where the collective memory is anchored, condensed, crystallized, sheltered and expressed."The most interesting thing is that it is not reduced to historical monuments, to the material, but also to the symbolic and functional (Nora, 2001).

The philosopher Eugenia Allier wrote, in connection with Nora's studies, a criterion that is revealing for my work:

[...] it is not just any place that is remembered, but the one where memory acts; it is not tradition, but its laboratory. Therefore, what makes the place a place of memory is both its condition as a crossroads where different paths of memory intersect and its capacity to endure and to be incessantly remodeled, reapproached and revisited. An abandoned place of memory is, at best, nothing but the memory of a place (Allier Montaño, 2018).

This is exactly what the Diablos Quizadeños Nueva Generación did: remodeling, revisiting and reapproaching dance from their perspective. We wanted to accompany them in that transition by showing their laboratoryThe dance is not only to dance, it is to rework their own history and memory through the individual and collective body, traveling the paths of their ancestors or where they lie today. Dance is not only dancing, it is reworking their own history and memory through the individual and collective body, traveling the paths of their ancestors or where they lie today.

Researching dance memory through ethnographic documentaries

After a review of everything discussed in this article, we conclude that ethnographic documentaries on African and Afro-American dances have accompanied the development of anthropology since its beginnings. In Mexico it has not been different; as we can see, seven of the documentary productions of the Costa Chica have been made by anthropologists/sociologists, the rest by filmmakers and communicologists.

The way of making them has been varying and, therefore, we can find different ways of narrating and collaborating with the communities in which we have been interested, because, as anthropologist Antonio Zirión says: "Documentaries show the reality they portray, as much as the subjective perspective and social conditions of their authors, and inevitably they are a product of the historical moment in which they are produced" (Zirión, 2021: 46).

As a production and post-production team, we have been moved by the process of revitalization of the Danza de los Diablos and related memories, such as the music, dance movements and costumes; but also by these places of memory where the dancers pass through, in a physical, mental and emotional journey: the homes of deceased people, the collective places where the dance emerged and their own diaspora. With this, the intention is to create an ethnographic documentary proposal that, as I mentioned, enhances the memories and resistances of these peoples. That, in this case, it collects the work of young people to revitalize a dance that was thought to be lost, in search of identity, meaning and encouragement.

The documentary in process starts from the fact that the research proposes a dialogue with the memory of a people, being aware that the result will generate other memories created not only by me as director, but also by the work team and the community itself (such as the moment when the first cut of the feature film was presented in El Quizá at the iv Afrodescendant Film Festival). In this sense, I have tried to articulate a discourse based on ethnographic experience, conversations with the Dance group and the community in general -who have entrusted me with their ideas, concerns and desires-, and collective anthropological and audiovisual analysis.

Film emerges as a possibility of preserving ephemeral fragments of life, as a memory that can be consulted and enjoyed later. This process implies a selection at the time of recording and I believe that here there is a point that suggests the following questions: what is selected for recording? Who does it? For what? For whom? We can use these questions to differentiate the way of filmmaking in the early days of documentary and the so-called collaborative or participatory documentary, which from my point of view is not one but many with the same intention, to contribute to the cultures, communities and / or people with whom we work from a critical place.

The ethnographic documentary as a container of community audiovisual memories is a profoundly necessary tool to work and discuss. We hope that our results and the questions that still accompany us constitute a starting point for further elaboration, construction and sharing of experiences and challenges with researchers, artists and those who are members of the cultures with which we collaborate.

Bibliography

Allier Montaño, Eugenia (2012). Los Lieux de mémoire: una propuesta historiográfica para el análisis de la memoria, Historia y Grafía. México: Departamento de Historia.

Colombres, Adolfo (1985). Cine, antropología y colonialismo. Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Sol/clacso.

Da Silva Ribeiro, José (2007). Doc On-line, núm. 03, diciembre, www.doc.ubi.pt, pp. 6-54. Brasil.

Florescano, Enrique (1999). Memoria indígena. México: Taurus.

Guber, Rosana (2011). La etnografía. Método, campo y reflexividad. Buenos Aires: Siglo xxi.

Grierson, John (1932). “First Principles of Documentary”, en Forsyth Hardy (ed.). Grierson on Documentary. Berkeley y Los Ángeles: University of California Press, pp. 145-156.

Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922/2001). Los argonautas del Pacífico occidental. Barcelona: Península.

Lora Krstulovic, Rosa Claudia (2024). “Reflexiones en torno al documental y la memoria social”, en Cristian Calónico Lucio y Rodrigo Gerardo Martínez Vargas (coords.). Cine: discurso y estética 2. Reflexiones desde las cinematografías contrahegemónicas. México: procine/uacm, pp. 209-215.

MacDougall, David (1998). Transcultural Cinema. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nichols, Bill (1991). La representación de la realidad. Cuestiones y conceptos del documental. Barcelona: Paidós.

Paniagua, Karla (2007). El documental como crisol. Análisis de tres clásicos para una antropología de la imagen. México: Publicaciones de la Casa Chata, ciesas.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia (2018). Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina. La Paz: Plural Editores.

Rouch, Jean (1995) “El hombre y la cámara” (1973), en Elisenda Ardévol y Luis Pérez-Tolón (eds.). Imagen y cultura. Perspectivas del cine etnográfico. Granada: Diputación Provincial de Granada, pp. 95-121.

Taylor, Diana (2013). O arquivo e o repertório: Performance e memória cultural nas Américas. Belo Horizonte: ufmg.

Varela, Itza (2023). Tiempo de diablos. México: ciesas.

Weinberger, Eliot (1994). “The Camera People”, en Lucien Taylor (ed.). Visualizing Theory, Selected Essays from V.A.R. 1990-1994. Nueva York y Londres: Routledge, pp. 3-26.

Zirión Pérez, Antonio (2015). “Miradas cómplices, cine etnográfico, estrategias colaborativas y antropología visual aplicada”, Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades. México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Iztapalapa, núm. 78, pp. 1-18.

— (coord.) (2021). Redescubriendo el archivo etnográfico audiovisual. México: uam/Elefanta.

Filmography

Documentary Africanías (1992). Rafael Rebollar. México: cna. Recuperado de: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGnHoimDAQE

Documentary Son de Artesa (2008). Dir. Sandra Luz López. México: uacm. https://vimeo.com/65174725?fbclid=IwAR389wh8BUAm3OgtDRS7OK50xpFWYqELAJ67xDdRzibaXNGRq0ITz1mnq9U

Documentary El juego de los Diablos (2008). Claudia Lora y Natalia Gabayet. México: tv inah. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdcOQBEVOwU

Teaser Diablitas, diablitos y almitas (2015). Dir. Isis Violeta Contreras. México: Ambulante. https://www.ambulante.org/documentales/diablitas-diablitos-almitas-danzando-la-vida-la-muerte/

Serie Afroméxico (2019). Dir. Ana Cruz. México: Canal 11. https://canalonce.mx/programas/afromexico#:~:text=Sinopsis,de%20África%20trasladados%20a%20México

Serie México negro (2021). Dir. León Rechy. México: Canal 14. https://www.canalcatorce.tv/?c=Programas&p=1853&a=Det&t=3634&ci=16985&b=ciencia&m2=5

Documentary Ruja al Son de los Diablos (2011). México: Colectivo Muchitos Audiovusual. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=94HNDEopqMY

Grupo de información en reproducción elegida (gire) (2021). Teaser Presentación de los Diablos Quizadeños Nueva Generación (2021). Festival Raíces, Coatepec Veracruz, México. Recuperado de: https://www.facebook.com/raices.colectivomaiznegro/videos/1569249276847309/

Rosa Claudia Lora Krstulovic is an ethnologist, documentary filmmaker and dancer. She researches Afro-diasporic dances in Latin America, focusing for several years on the study of the dances of devils and round dances. Her areas of interest are memory, cultural transmission, documentary and heritage. She has made ethnographic documentaries, as well as anthropological research for independent documentaries and documentary series of the inah. Currently, she directs the Afrodescendencias Arts Festival and is a post-doctoral researcher at ciesas-cdmx with the theme "Collaborative strategies for the continuity of the Afro-Mexican dances of the Costa Chica".