Derecho de playa: my experience as an anthropologist in documentary film production

Interview with

*

Received: February 1, 2018

Acceptance: February 26, 2018

Abstract

The interviewee describes her work as a sociologist and anthropologist in documentary film production and reflects on it; specifically through the collaborative experience in the documentary Derecho de playa.

Keywords: collaboration, documentary film, social investigation, film, production

Beach Right: My Experience As an Anthropologist in Documentary-film Production.

The interview describes and reflects on Alfaro Barbosa's work as a sociologist and anthropologist in documentary-film production, specifically through the experience of collaborating on the documentary entitled Derecho de playa.

Keywords: Social research, documentary, film, production, collaboration.

Cristina Alfaro is part of the family of ciesas West. He is currently studying the Doctorate in Social Sciences in this unit, but he already studied here the Master in Social Anthropology, and even before, when he was still in the degree in Sociology at the University of Guadalajara, he began to form part of teams that investigated on the presence of indigenous people in this city. Since 2004 she has worked on issues related to indigenous migration in different contexts, but for her doctorate she decided to change, and the subject of her thesis is women who seek alternatives in care at birth. At the same time that she has become an established researcher, Cristina has developed a career in the production of documentaries, such as Derecho de playa, which premiered in 2016, and at the Guadalajara Film Festival that year, the Jalisco Academy of Cinematography awarded him the award for best Jalisco feature film. From this, we talked with Cristina about her experience in the relationship between both spaces of knowledge production.

Santiago Bastos: Good afternoon, Cristina. Since I met you in the Master's degree, you have been involved in the world of documentaries, and this parallel career has always caught my attention, which has been around for a while. How did you get into this space, and how was that first experience?

Cristina Alfaro: My foray into audiovisual work happened in a somewhat unexpected way, when a couple of filmmakers became interested in using my undergraduate thesis, which was on indigenous women who worked as domestic workers here in Guadalajara, as a basis for a Documentary that ended up called Here on Earth and premiered in 2011.

I had no idea what this would imply, I was totally removed from topics such as cinematographic narrative and the structure of a script. That first approach was certainly bumpy. On the one hand, the documentary allows us to show in images what we explain in the social sciences through words; but they have different rhythms and forms, the times of audiovisual production are different from those of research, and without the opening to dialogue these activities become conflictive. We also had tensions, because the director privileged the image itself, and on the other hand, I was more concerned about people.

I learned that interdisciplinary dialogue is important. Anthropological research gives priority to information gathered in the field, through conversation and observation. Audiovisual production records images and sounds of reality, through the camera. If it is possible that these tasks are not exclusive, and if the production of a documentary is preceded and accompanied by a reflective process of investigation and analysis, the result is undoubtedly enriching.

SB The last work in which you have participated has been the documentary Beach Law, which has been presented at festivals such as the one here in Guadalajara or the one in Trieste in Italy, but I understand that also in academic fields such as the Mesoamerican Studies Congress in Guatemala What is it about? How did you treat this issue? Did it have to do with your Master's thesis, which was taking place on the beaches of Jalisco?

AC No, Beach Law does take place on the southern coast of Jalisco, but it has nothing to do with the street vendors I worked with on the thesis. It deals with the way of life of fishermen from different cooperatives in that area who are facing various conflicts, including the difficulty of accessing the sea due to the constant closure of beaches for privatization.

Our interest in making this documentary arose in mid-2012, while we were following the work of the journalist Analy Nuño, who was covering the issue of the privatization of these beaches. She was going to learn about the situation of the residents of Tenacatita, who had been evicted from houses, hotels and restaurants on the beach in August 2010. As we spoke with them, we realized that there was a story that had to be told through a documentary: the privatization of the beaches besieged the entire region; Tenacatita was just one of the many stories of dispossession that the inhabitants of the coast have lived.

SB And so how was the process? How did they get the funds?

AC In that first approach we met Don Rodolfo, a fisherman who loved his trade, but who for physical reasons had to move away from that profession that he liked so much. We thought about seeking financing to tell their story through a short film and thus have the opportunity to return to the region to continue learning more about the subject and to be able to propose the production of a feature film later.

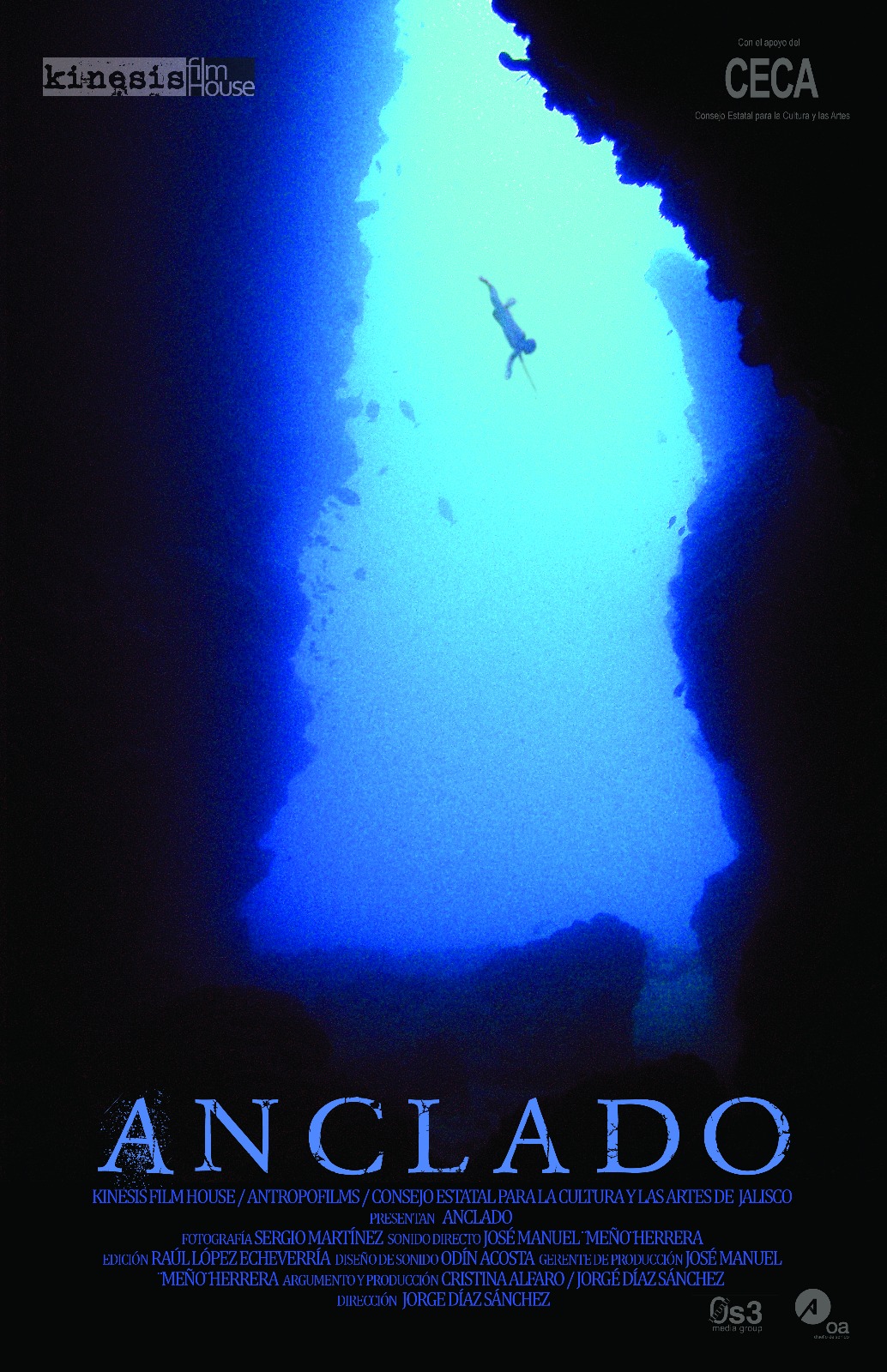

Thus, in 2013 we got a scholarship from mint –The State Council of Culture and the Arts of Jalisco– for the production of the short film Anchored, which is a portrait of Don Rodolfo. This allowed us to return to the area and delve into the reality of fishermen's cooperatives to generate the proposal that gave rise to Beach Law, which was later financed by foprocine-imcine.

SB What has been your work as part of the production teams in which you have participated? What were your tasks at Anchored and Beach Law?

AC In general, within the team my tasks have been mainly research, relationship with the characters and also the continuous analysis of reality; but throughout the process I have also collaborated with production tasks.

The cinematographic production of documentaries is distinguished from the mere audiovisual record used in anthropology because the cinematographic language is used to construct a narrative. This implies the conjunction of specialized technical elements in the three stages: pre-production, production and post-production.

In pre-production I had a double task, research and planning; work I did together with Jorge Díaz Sánchez, who is a filmmaker and is the director of the documentary. The first step is to establish the situation to be analyzed, and it is necessary to know the particular context in which the initial approach takes place. To do this, we carried out a bibliographic and hemerographic review and we also had conversations with the fishermen and key figures. We sought to understand different aspects of the region, from Barra de Navidad to Punta Pérula; where the stories of dispossession and power struggles frame the daily life of its inhabitants and reconfigure their social and economic activities.

Regarding planning, at this stage the elements for production were established: choosing a crew –the production staff–, the specialized equipment team for the needs of the subject, and also the scheduling and budget.

SB And during the production phase, what was your responsibility?

AC There, my responsibilities were related to my anthropological training: observation and listening were my main activities. But unlike anthropological fieldwork, which is usually an individual task, documentary film production involves collaboration between a group of specialists in the field, and the use of specialized technical equipment: camera, lenses, microphones, etc. For Beach Law, the production crew consisted of four members: director, photographer, sound engineer and myself, the researcher.

SB You were the only woman on the team, how did that affect that?

AC Fishing is a mostly male activity and fishermen felt much more comfortable interacting with my companions. I did not seek to interfere in this situation; the comfort of the characters is crucial for the camera, as it is for the informants of any investigation. I am not saying that I stayed away from any interaction with the fishermen, on the contrary, my relationship with them was more personal than related to their trade; They cared about my well-being and repeatedly questioned how I felt traveling with three men.

The presence of women in fishing activity is practically nil; their participation occurs in the preparation of the fish product, at home or in restaurants. I did seek to approach them in those contexts, but the results were not fruitful; as they felt they were alien to the fishing activity, they did not consider their participation in the documentary to be of importance, and as the documentary's plot centered on fishing, they stopped seeking their incorporation. If I had been doing anthropological fieldwork alone, I would have given myself the time and found a way to break with this distance; the fact of being more members of the team allowed to turn the situation around.

Despite this gender distance established by the fishermen, the exercise of constant dialogue with the director allowed us to carry the analytical thread in the production process, both for the choice of characters and situations to follow and for the generation of thematic axes for the interviews.

SB The documentary is about various cases, what are they? How was the relationship with the protagonists?

AC The central theme of the documentary is fishing in Costa Alegre, southern coast of Jalisco; We work with various cooperatives: those of Barra de Navidad, Careyitos, Chamela and Punta Pérula. The state of access to the beach and the fishermen's housing in each context modified our way of relating to them. In some cooperatives our work was limited to the limits of fishing, especially in those where the entrance to the sea is disconnected from the fishermen's house. In one of the smaller communities, on the other hand, there was the opportunity to live with the families, wives and children of the fishermen, they invited us to eat and even to spend the night in their houses. This made it possible to generate a personal bond that has been maintained to this day.

SB In social research, great care is now taken with issues of ethics and the participation of subjects in the process. How does this apply in the case of the documentary?

AC As in anthropological research, documentary production needs a constant questioning of the ethical implications of our activity in relation to the characters, the registration of their image and the decisions made regarding the plot to be developed.

During the production of Beach Law this was always present. During the production process we seek to be as less intrusive as possible, respecting your privacy, time and space. An example of this is the decision to use exclusively natural light during filming, leaving in the background the technical value of photography that is achieved using controlled artificial light; to have used artificial light would have implied a greater interference in their daily life.

SB I am struck by the fact that in the documentary it is not quite visible that the fishermen were people who were fighting for their territory; appears in the narrative thread, but we do not see images of struggle.

AC Indeed, that has been mentioned to us in various presentations, and it really was a deliberate decision. I agree with Victoria Novelo that it is important to seek and work on emotions as well as the information that audiovisual work wants to convey; but I also consider it equally important not to ignore the personal, political and social interests of those involved.

When we began to collect the stories of dispossession on the beaches of the southern coast of Jalisco, we encountered fishermen who were not willing to tell their story in front of a camera; they assumed that their registration was a risk, since their life and profession were threatened. They had reasons for this: they had just assassinated Aureliano Sánchez Ruiz, a representative of one of the cooperatives that was fighting against the closure of the beaches and the dispossession of land in the region; and just at the end of last year they assassinated Salvador Magaña, a social activist from the coast.

Then, these stories were told carefully when the camera was not present, the audiovisual record modified their speeches and attitudes. Given the refusal to tell this part of their reality, the fishermen proposed to show their trade, and although this modified the original argument, we decided to respect their decision. This generated expectations in them, which they imagined excitedly and commented on how their trade and daily work could be shown in the best way. With this we achieve a participatory and dialogical reflection of their interests and ours when wanting to film the film. At all times they were given authority as specialists on the subject, only they could talk about it and show its reality.

SB Then, there came a time when they were like part of the team… ..

Let's say there was an ongoing dialogue. An example of this are the maritime images recorded by Neftalí, a diver with innate qualities for photography, who was in charge of recording his brother's fishing skills under water with a small underwater camera. The experience of collaboration with Nefta was surprising, they narrated at different times how they worked underwater and their passion for the beauty of the seabed. Undoubtedly, the recording of these images would not have been possible without their participation, and it shows the importance of collaborative work with those involved in the reality to be taught.

SB Seen now, after almost ten years combining anthropological research with documentary production, how do you evaluate the relationship between the two; what have you learned?

AC My experience through documentary production has been a personal and professional learning journey. Anthropologists know and analyze a reality that is expressed through words. Documentary cinema does so through a sequence of images –and testimonies if it is the case– in congruence with an argument. This trip has been a collaborative exercise based on continuous interdisciplinary dialogue, seeking to go beyond the register. By including cinematographic language in this analysis of reality, its essence is necessarily incorporated: building a cinematographic journey that provokes emotions in the viewer. That is, it seeks not only to inform and present information related to a reality, but also to leave a lasting emotional imprint through a solid visual and discursive argument.

In my work as a sociologist and anthropologist, I have learned to observe and listen from contemplation and dialogue, giving the necessary time to each situation and interaction to later analyze and write; it is a continuous work of understanding reality, between the senses and theory. My foray into audiovisual production has allowed me to access other forms of recording and approaching a reality and its actors.

The dialogue between research and audiovisual production is not easy, however, when carried out well, it is extremely useful and enriching. Audiovisual media are ideal for taking the work of the social sciences beyond specialized academic and scientific circles, and thereby bringing the results of an investigation to a wider audience. This collaborative exercise has allowed the documentary to be shown at film festivals and in academic settings, thus generating a dialogue between audiovisual production and the social sciences.

SB What are they up to now? What are the plans when you finish your PhD? Do you think you can continue to combine both ways?

Well, it would be the ideal. It is very clear to me that job options within the academic world are scarce, so we need to create other spaces for work and reflection, to be a bit self-managed. Antropo Film House is the production company that we created thanks to this collaborative work with Jorge Díaz Sánchez, to generate projects of interdisciplinary dialogue between cinema and research. At the moment we are working on two feature films, one that is in the pre-production process with the Triqui basketball players and the other in an early stage of production, in collaboration with researchers from ecosur. Here we go.

Data sheet

Director: Jorge Diaz Sánchez

Screenplay: Jorge Díaz Sánchez, Cristina Alfaro

Production: Jorge Díaz Sánchez, Cristina Alfaro

Photography: Sergio Martinez

Direct audio: Jose Manuel Herrera

Edition: Raúl López Echeverría

Music: Kenji kishi

Sound design: Odin Acosta

Duration: 75 min. Mexico 2016

Producer: Kinesis Film House, AntropoFilms, imcine, foprocine

Thank you, thank you for allowing us to see reality through you. Congratulations for your courage and effort to make the reality in which we live known to the world. All the people in all your movies, but especially those of Derecho de playa and Anchored They are people of great value. Like your whole team, Jorge. I would very much like thousands of people to have the opportunity to see your films and your interviews. All your projects are beautiful because they have a lot of heart. Many congratulations!