Between the visual and the narrated: approaches to the collection of photographs of Mexico at the American Historical Exposition of 1892.

- Marisol Domínguez González

- ― see biodata

Between the visual and the narrated: approaches to the collection of photographs of Mexico at the American Historical Exposition of 1892.

Receipt: September 25, 2024

Acceptance: January 22, 2025

Abstract

In 1892 Mexico participated in the American-Historical Exposition of Madrid for which it made an exhibition proposal that included a collection of 768 photographic objects. This article sketches a research work done on these materials: it unfolds ways of approaching the images by considering their contextualization as a set and their relationship with other documentary sources, as well as emphasizing their construction as a documentary corpus that oscillates between the visual and the written and that works to address aspects of the presence and representation of the country in the exhibition.

Keywords: Historic-American Exposition, Photographs, assembly, indigenous population, visual records, pre-Hispanic vestiges

Visual and narrative approaches to the Mexican collection of photographs at the 1892 Columbian Historical Exposition

In 1892, as part of its exhibit at the Exposición Histórico-Americana (Historical American Exposition) in Madrid, Mexico presented a collection of 768 photographic objects. This article investigates these materials, revealing different ways of engaging with the images by contextualizing the collection and its relationship with other documentary sources. It also emphasizes how they were constructed as a body of materials that oscillates between the visual and the written, serving to explore aspects of the country's presence and representation at the exhibition.

Keywords: photographs, Exposición Histórico-Americana, Historical American Exposition, display, visual records, Pre-Columbian artifacts, Indigenous population.

Introduction

This article1 addresses issues arising from research done with and on photographic materials. It is an approach to the collection of photographs that Mexico exhibited at the Historic-American Exposition in Madrid in 1892, which focuses on the methodology followed to integrate them as a documentary corpus, to then expose the characteristics of the photographic collection and some aspects of its operation and contents.

I begin with a brief synthesis of the research conducted in order to frame the approach to Mexico's photo collection. Next, I contextualize the exhibition, Mexico's participation and proposal, as well as the conformation of its photographic collection on display. Then, I focus on the research processes and methodology, that is, I present the written and visual materials and documents I used in the research, and explain how I integrated them as sources. Finally, I dwell on some particular cases and issues related to the functioning of the photographic collection of Mexico and the visual representation of the country in the exhibition, which become evident thanks to the crossings between documentary sources of different nature.

The intention is to highlight the process of integration of a photographic corpus that combines the visual and the textual to put on the table ways in which a photographic collection can be approached, which constitutes, in this case, a useful documentary source not only to study the representation of Mexico in the Historic-American Exposition, but also to investigate various social processes.

The research

The approach to the photographic collection that Mexico presented at the Historic-American Exposition derives from a study of the participation of the state of Yucatán in it. My interest in this group of 54 photographs led me to analyze the 768 photographic objects that were exhibited. To delve into the photographic materials and understand their behavior it is necessary to contextualize their presence in the exhibition: to consider the specificities of their inclusion, location and deployment within the logic of the Mexican galleries, for which it was necessary to know the general structure of the exhibition and the discursive and spatial structure of the section corresponding to the country; to review the organizational processes of their participation in this event, the design of their exhibition proposal and the production, compilation and integration of their collections, in particular, the photographs. It was important to try to reconstruct and maintain an overall vision, since the photographs were not consumed in isolation, but in the midst of thousands of objects of various kinds. In other words, the photographic collection was part of a selection of objects that served as a letter of introduction to Mexico abroad.

The Historic-American Exposition and Mexico's participation in it.

The Historical-American Exposition of 1892 was one of the most important events organized by Spain in the framework of the celebrations of the iv centenary of the arrival of the Spaniards to the American continent. It was an international historical exposition that brought together a few European countries, the United States and most of the American countries that had been part of the Hispanic monarchy. Its headquarters was a building recently constructed on the Paseo de Recoletos in Madrid, destined to house the library and the national museums. On its first floor was installed the American-Historical Exposition, which opened its doors to the public on October 30, although it was officially inaugurated on the afternoon of November 11, 1892, with the presence of Queen Regent Maria Cristina of Habsburg and the kings of Portugal (Del Blanco, 2018: 79; El Siglo Diez y Nueve2 November 1892: 3).

The American Historical Exposition (eha from now on) intended to show the state of the American peoples when the Spaniards arrived and at the time of the immediate conquests (Del Blanco, 2017: 54-55).2 In the text accompanying a plan of the exhibition, it was announced that the materials on display, "in addition to serving as recreation and instruction for the visitor, will be sources of study for the scholar and will contribute to clarify many points still obscure or not well understood, which exist in the confusing history of the peoples who populated the beautiful American land".3 This window into the past would serve to strengthen Spain's ties with the countries of the Americas and, at the same time, underpin its importance in the history and development of these peoples.4

The Mexican government, through the Ministry of Justice and Public Instruction, brought together a group of intellectuals dedicated to the historical sciences to design the exhibition proposal and organize the country's participation: the Junta Colombina; subsequently, it formed a commission that would be in charge of installing the Mexican section in Madrid.5

According to the Catálogo de la sección de México (Mexico Catalog from now on), the Junta Colombina would set itself the task of "collecting objects that would reveal the progress of our aborigines, both in pre-Hispanic times and after the Conquest, and the state they are currently in" (1892: 7). In order to gather the materials to be exhibited in Madrid, he resorted to the selection and reproduction of objects from the National Museum, organized expeditions to explore archaeological sites and visit different localities of the country, asked for the collaboration of private individuals from the provinces and called on the state governments and political headquarters of the federal territories to send materials or specific pieces that were known to be in their custody.

The Mexico section, at the back of the building, would occupy five adjoining rooms bordering an inner courtyard. These housed more than 18,000 pre-Hispanic, colonial and nineteenth-century objects of various kinds (maps, books, photographs, paintings, costumes, plaster reproductions, objects made of stone, wood, cloth, clay, etc.).6 In the last three rooms, 768 photographic objects were exhibited: 767 single photographs and an album that included several prints. This group represented 4.3% of the total number of pieces that the country exhibited in its five galleries. Although the number of photographs exhibited is tiny in relation to the total number of objects, it becomes more relevant when the context of their production and integration is known.

Photographs of Mexico and the integration of a collection

When investigating how Mexico's participation was organized, data emerged that highlight the importance given to the production and collection of photographic materials: from the beginning of the process of planning the contents and design of the Mexico section, it was thought to include photographs and, in addition, it was sought to collect them throughout the length and breadth of the country.7 The Mexico Catalog points out that "Of the orders that the Junta Colombina was issuing, two were of a general nature and bore immediate fruit: the circular addressed to the Governors of the States so that they would send photographs of ruins and indigenous types, and an exhortation made to private individuals to provide objects for the Exposition [...]" (1892: 17). The prompt collaboration of the states that sent photos may be due to the fact that the images were devices that allowed the governments to show certain aspects of the places they administered.

The production of photographs was one of the tasks of the Junta Colombina to form "a collection of photographic views of the archaeological monuments that exist scattered in various regions of the country, and another collection of types of indigenous races" (Circular of the Junta Colombina, 1891). The desire to integrate a photographic collection that would give an account of the indigenous population and pre-Hispanic monuments was not new; what was new was that it was actually achieved. The concentration and exhibition of a photographic collection of this magnitude, made up of materials from different regions of the country, was unprecedented.8

To achieve this undertaking, he proceeded in three ways: he used photographs generated in a couple of recent expeditions to the state of Veracruz, undertaken by the National Museum, and organized new expeditions and visits to other parts of the country -Chihuahua, Chiapas, Tabasco, Tlaxcala and Puebla- in order to obtain more materials. To enrich the collection, a provisional photographic workshop was set up inside the National Museum, where hundreds of pre-Hispanic pieces from its collection would be reproduced (Mexico Catalog, 1892: 9, 13, 20-26; 1893: 365-366, 385-386).9 In addition, as I have noted, a request was addressed to the governors of the states and the political chiefs of the territories to send photographs; some of them "took great pains to obey the wishes of the Board, and forwarded very remarkable collections [...]" (Mexico Catalog, 1892: 17). It is interesting to distinguish that more than 35% of the photos came from shipments from the governments and territories that responded to the request, almost 40% was the product of expeditions and visits, while the series produced at the National Museum represents just over 20%.

The photographic collection includes images from the states of Chiapas, Chihuahua, Colima, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, Sonora, Tabasco, Tlaxcala, Veracruz, Yucatán and Zacatecas, as well as the Federal District and the federal territories of Baja California and Tepic (Domínguez, 2023: 177).

The group includes records of people, work scenes, monuments and historical and archaeological remains, utilitarian objects, pictorial and sculptural works, codices, landscapes, urban and rural views, civil and religious architecture, public buildings and dwellings. These subjects represented in the images refer to the pre-Hispanic and colonial periods, but also to a nineteenth-century or contemporary present of the exhibition. In this sense, the photos are not limited to the temporality requested by the organizers of the exhibition. ehabut extend it.

Sources, holdings and process of locating the photographs

To locate and identify the photographs of the Mexican rooms in the eha I worked with the Mexico Catalog (1892-1893), with the collection of the National Photographic Archive of the inahthrough its digital consultation repository (the Media Library), and with the facsimile edition of the Catalog of the National Museum's Anthropology Collection of 1895 (2018).

The Mexico Catalog is a written material that served as a starting point for tracking down and working with the set of photos of Mexico. It is signed by Francisco del Paso y Troncoso, who was a member of the Junta Colombina and president of the commission assembled in Madrid, responsible for the installation of the Mexico section in the eha. It is organized in three volumes, although only the first two were published.10 It reviews the organization of the production and collection of objects and, in general, the work involved in participating in the exhibition; it describes various aspects of what today we would call the museographic design of the galleries and includes a sort of summary of the objects exhibited in which it lists, describes and/or comments on them, as the case may be.

The catalog describes the subjects or themes of the photographic images and sometimes incorporates data on their supports as legends or annotations on the back of the secondary support. In addition, in this document you can find information on the location, the furniture used and other types of structures in which the photographs were placed, the formats, the provenance and sometimes the attributed authors. It is pertinent to point out that the catalog does not include the images as visual elements, it only contained their descriptions or written references. This material provided a global view of the photographs exhibited in the Mexican galleries, which facilitated their understanding as a whole and not as isolated pieces.

On the other hand, the search for and recognition of the photographs - as visual objects - was carried out mainly in the repository of the Fototeca Nacional del Perú. inahThe images were compared with the information from the Mexico Catalog to identify them.11

The above-mentioned facsimile of the Catalog of the National Museum's Anthropology Collectionedited by Teresa Rojas Rabiela and Ignacio Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba (2018).12 This catalog recorded the contents of a renovated anthropology section of the National Museum in 1895, which had included part of the photographic collection from the eha. It should be noted that the original 1895 catalog did not include the images -as visual elements- either, only written references. The value of the facsimile lies in the fact that its editors included an appendix with the images of the 1895 anthropology collection that they were able to locate within the National Photographic Library. This made it easier to identify the images I was looking for, particularly those related to ethnographic records. These visual images were contrasted with the written descriptions of the photographs in the ehaThis served to recognize some of them, but also to discard others that at some point were thought to have been part of the 1892 exhibition and thus correct the misunderstanding.

Before continuing, it is pertinent to point out that the image is considered as one of the parts of the photographic object. That is, we speak of photographs to refer to objects composed of the image, the primary support or photographically sensitized paper, the secondary support on which the previous one is placed, in addition to elements such as inscriptions, stamps, legends and other marks that are incorporated on these two supports -sometimes at the time of their production and others later- in the path that the photographic object follows (Aguayo Hernández, 2008: 141-142).13

It would be ideal to find the original photographs exhibited in 1892, with their respective images and supports with marks and traces of its passage through the eha. However, we should not lose sight of the fact that photos (in general) could be reused for various purposes. For example, a photo produced as a personal portrait for private consumption could later appear in a newspaper, as a postcard of a place or serve as an advertisement; that is, it became a public circulation. It is possible that the photographs of the eha -or the images they contain- have been reproduced before and after the exhibition. Suffice it to think that many of them would serve as scientific study materials after the exhibition, a subject I will address later.

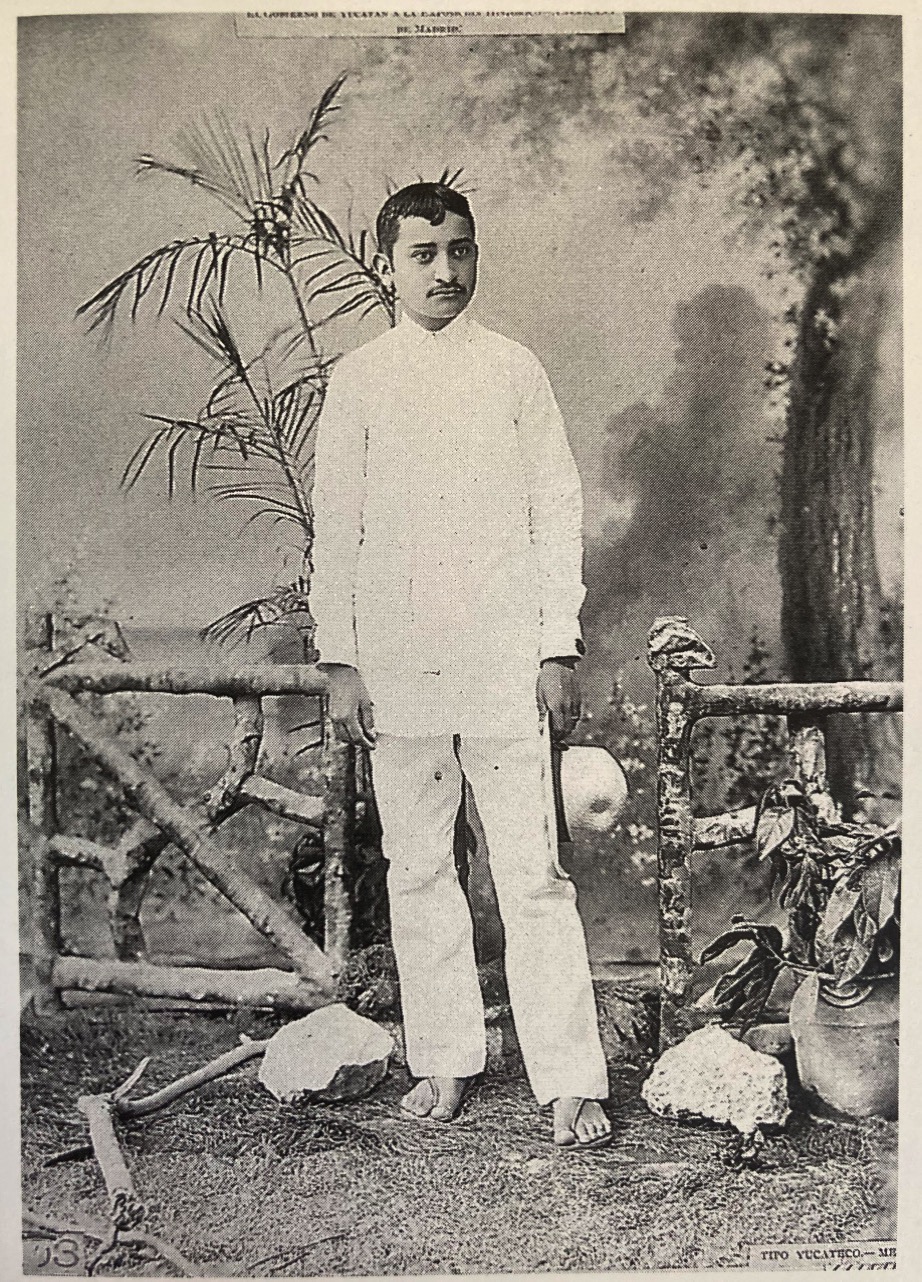

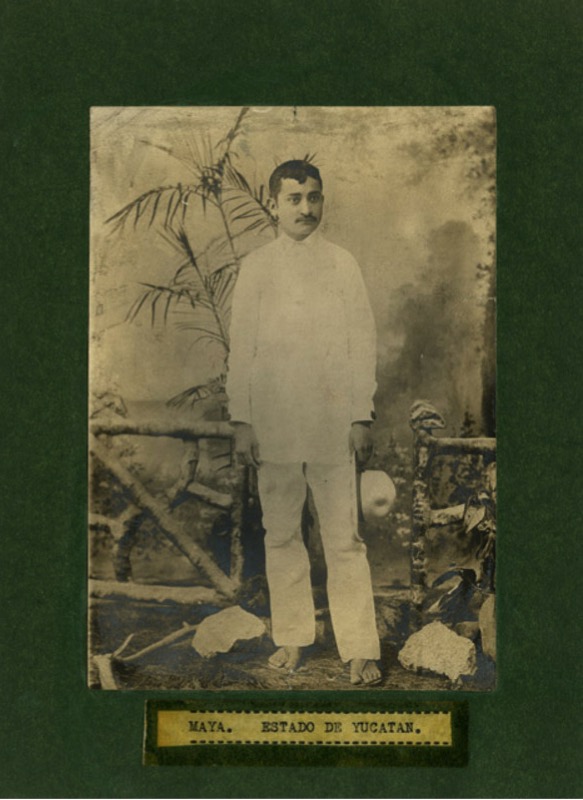

Hence, in the contemporary search process one may come across photographic objects that are not necessarily the ones that were physically exhibited in Madrid, but are derived from them, or several photographic objects that contain the same image or an edited version, on secondary supports with captions or annotations different from the originals (Aguayo, 2019). An example of this reproduction and edition within the collection of photographs of Mexico in the eha is the photograph of the Yucatecan mestizo belonging to the series sent by the government of Yucatan (see image 1).

This is a vertical image that places at the center of the composition the figure of a young man standing upright and full body. It is a studio photo that uses a landscape backdrop and objects such as a wooden fence, a flower pot in front and a couple of logs and stones on the ground to simulate an outdoor shot. The wooden fence cuts the image in half and divides the space represented into an open area and a more confined area close to the viewer, perhaps the lot, on whose threshold the mestizo poses. The rigidity of his frontal posture is broken when he slightly advances his left leg and looks to the side. The man wears the mestizo's luxurious costume: long or Filipino linen or white cotton shirt that falls loosely to mid-thigh, with a pair of denim or white cloth pants. He wears espadrilles and holds a hat made of jipijapa, a thin palm leaf fabric.

From this image exhibited in the ehaA similar one was identified, cropping a portion of the right side, eliminating the flowerpot in the foreground and part of the tree in the backdrop. With this image a new photographic object was created, since it is placed on another support and with a different caption from the original: instead of the title "Yucatecan-mestizo type" consigned for the original, the caption "Yucatecan-mestizo type" is placed on the right side of the image. ehasays "Maya. State of Yucatan" (see image 2). In other words, a figure once exhibited as a mestizo from Yucatán, a category distinct from that of Maya Indian, became a representation of a Maya man without alluding to a racial mixture.

Of the collection exhibited in the Mexico galleries, made up of 768 photographic objects, I was able to visually recognize and locate 218 photographs -or derived images- within the collection of the Fototeca Nacional, with the exception of three images that are located in the collection Legado de Teobert Maler (1842-1917) of the Ibero-American Institute of Berlin.14 As anyone who researches photographic materials from the 20th century can tell you xixI was confronted with many absences and gaps -perhaps losses or destructions- within the Mexican photographic collection in the eha.

In this process of searching for photos,15 have at hand the Mexico Catalog meant having a kind of narrated guide to the images that provided a complete view of the collection. A guide with sufficient precision to make more evident the gaps or missing elements in the photographic corpus of Mexico exhibited in the ehaThose images that have not yet been located despite the fact that the task of tracing photographs and images was constant in the investigation.

The formation of the photographic corpus with visual images and written descriptions

Undoubtedly, it would be optimal to gather the photographs exhibited in order to be able to work with this complete visual corpus.16 Before this ideal scenario, which is still far away, there is the real present scenario in which part of the images in the collection have been identified and there are written descriptions of all the photos. It seems pertinent to make use of these descriptions and not limit them to being only a support in the search for the original visual sources. That is to say, to choose to consider both the visual materials found -identified as part of the eha- as well as the descriptions of the photos articulated in the Mexico Catalog. The proposal is to build a corpus that unites the photographs in their visual and narrated versions: to juxtapose the visual and the textual in order to enrich the general perspective of the photographic set, but also to approach the issues and themes represented in it. This is the documentary body that can be worked with and that can be used to get to know and approach what Mexico showed in the Madrid galleries.

It should be noted that the descriptions of the Mexico Catalog present what is contained within the picture and also comment on some aspects related to the people, places or things that appear in the image. However, apart from the visible elements -people, things, places, landscapes, actions, customs, etc.-, photographs as objects have information in their supports and in their own materiality, for example, legends, titles, signatures, stamps or annotations.

Some of the photos that came into the hands of the Junta Colombina de México had captions pasted on the image and on the front of the support or notes on the back of the secondary support containing titles and comments on what was represented in the image. When exhibited, these elements were not necessarily visible to the visitor, either because they were on the backs of the supports or because the location and/or mounting of the photo prevented them from being read. The catalog texts were also not read by visitors.

However, today we are interested in them because they are data that can contextualize what is presented in the image, the solutions chosen to represent something and to build narratives on various issues; they help to draw the meaning that was given to hundreds of records that were integrated into the photographic set exhibited. The recovery of these two types of information provides clues as to where the viewer's gaze was intended to be directed and the intentionality of the photos.

Del Paso, at the time of drafting the Mexico CatalogHe retrieved the information from the photo supports and, on occasion, when it was too messy or had errors, he considered it necessary to correct or expand it. For example, from a series of photos of "ruins of Yucatan" that the government of that state sent, Del Paso noted that the subjects of each image "were indicated from Yucatan at the bottom of the pictures, but as the inscriptions have been made with much carelessness, I will have to rectify some of them" (Mexico Catalog, 1893: 31, 36). Such was the case of a photograph that showed structures from Chichén Itzá and claimed to be from Uxmal. In particular, this series gathered enlargements of vestiges of Mayan sites already known and photographed years before the exhibition -Chichén Itzá, Uxmal, Kabah, Labná and Sabacché- without indicating the authorship of the photos. It is likely that he gathered images by different authors.

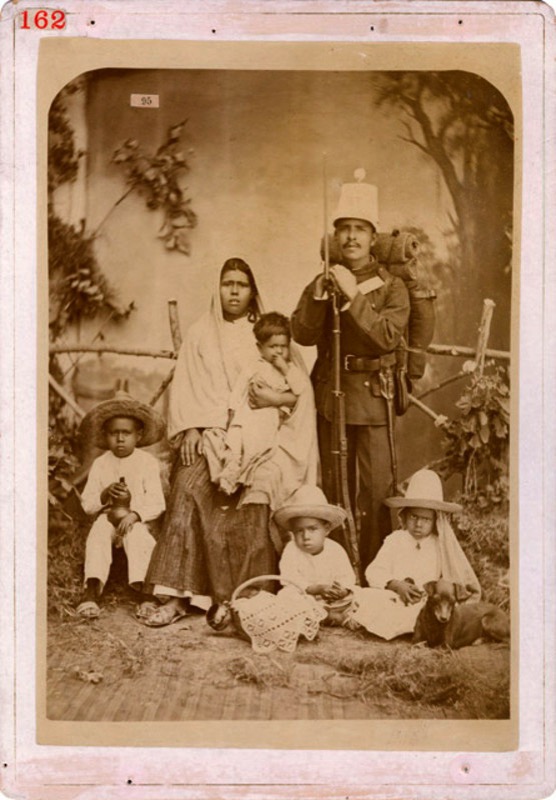

In this sense, when contrasting the photographs identified visually with their written descriptions, there were coincidences between the information written on the photos themselves and what the catalog consigned, but differences or nuances were also detected. The information that the senders of the photos wanted to make known could differ from what the Junta Colombina wanted to emphasize. One group record from the territory of Tepic stands out, which is presented in the catalog as a "family of the indigenous race that lives in the cities" (see image 3). The image shows a family composed of the father, who is wearing a federal army uniform and holding a bayonet, the mother carrying one of her children on her lap, and three children sitting on either side of her, all facing forward. In his description, Del Paso clarifies that "the sender believes that it presents characters of having been mixed with other races," but that "the appearance of the individuals is of an almost pure Indian race" (Mexico Catalog, 1893: 256-257). The commentary shows that Del Paso made corrections when he considered that the information contained in the photos sent was not accurate. What is interesting is that, in general, he made explicit the error he was correcting or at least indicated that he would make a modification.

The dialogue of the photographic corpus with other written and graphic documentary sources

The photographic corpus of Mexico, made up, as I have said, of elements of a visual and textual nature, can be put into dialogue or confronted with other written and graphic documents. In addition to the two aforementioned catalogs, there is the Catálogo general de la Exposición Histórico-Americana de Madrid 1892 (1893), which brings together the catalogs of the other participating countries; the Suplemento-guía de las Exposiciones Históricas (1892),17 of the Madrid newspaper El Díawhich was a brochure with a schematic plan of the facilities, a general description of the contents, and even some illustrations of exhibits; the Plano de la Exposición Histórico-Americana (1892), which shows the spatial distribution of the countries in the headquarters; a document by Jesús Galindo y Villa (1892), who was part of the Mexican commission in Madrid, which includes a sketch of the rooms in Mexico showing both the spatial division and the distribution of the basic furniture; the Guía para visitar los salones de historia del Museo NacionalThe first edition of the report, written by Galindo y Villa (1899), includes references to some photographs of the ehaa series of ten photos with views of the interior of the halls of Mexico;18 the "Álbum Exposición Histórico-Americana de Madrid 1892",19 with records of various sections, including three views of the Mexico section; a circular issued by the Junta Colombina to the state governments (Circular of the Junta Colombina1891); in addition to a hemerography of the period, for example, the reviews of the Mexico section of the Spanish archaeologists José Ramón Mélida Alinari and Eduardo Toda y Güell in the Spanish newspapers La Ilustración Artística and The Spanish and American Enlightenmentand notes and notices that reported on the country's progress and preparations for the eha in national newspapers such as El Monitor Republicano and El Siglo Diez y Nueve.

This dialogue of the photographic corpus with other sources allows us to unveil interesting scenarios and aspects of how the country was (re)presented in the eha and how the photographic collection worked. In the following, I address some cases related to both the contents of the photos and the editing.

Considerations on what the photographic collection of Mexico in the eha

The photographic collection is dominated by records of indigenous types and pre-Hispanic monuments and objects. With a couple of exceptions,20 most of the latter were produced purposely at the National Museum for the exhibition, the monuments were collected on expeditions and through ad hoc requests, and the types were mostly collected thanks to the response of the states to the request made by the Junta Colombina, although they also come from the raids promoted by the latter.21

When confronting the photographs with the narrative of the Mexico Catalog, the General Catalog, the Supplement-guide and reviews in the Spanish press, it is clear that Mexico shows issues that are not always in line with the purpose of the exhibition. Unlike the records of pre-Hispanic pieces and monuments that fit in well with the objective of the ehaThe series of indigenous races represented a contemporary component that did not quite fit with the intentions of the exhibition.

Through his photographic collection, Mexico boasted a grandiose indigenous past, especially through the records of vestiges of monumental constructions and, at the same time, presented a contemporary indigenous population with varying degrees of "civilization" and miscegenation, which is emphasized mainly through dress.

There were 178 photographs of "ethnological types", i.e., records of indigenous and mestizo people from different regions of the country. In the Mexico Catalog are presented as types or Indians of a state or territory, with the exception of a series entitled "Workers of the state of Zacatecas" and another "Descendants of Cosijoeza, king of Zaachila", and their individual descriptions specify the "Indian" or mestizo status of the persons represented. In other words, a constant in the titles and descriptions of the catalog is to point out the racial component and the purity or mixed race of the persons recorded. In addition, some thirty photos associate people with an occupation or with general jobs such as artisan or more specific jobs such as marimbero or escobetero, by means of objects and tools typical of the trade represented or through a text -either in the photograph itself or in the descriptions-.

The group of ethnological types makes up almost a quarter of the photographic ensemble. Together with a collection of costumes of some of the indigenous peoples of the time and other contemporary objects, the photographs of types constitute an ethnographic pole in the fifth room and tilt the balance towards the representation of the present, within an exhibition of a historical nature. Thus, these images were in line with the objective that the Junta Colombina had stated from the beginning: to show the state of the indigenous population; however, it was far from what the Spanish organization was primarily interested in: to show the state of the population and the territory at the time of the arrival of the Spaniards and the first conquests. In a review of the Mexican rooms, Mélida Alinari celebrated the following: "Fortunately, very few objects belong to modern times; all the rest are from pre-Columbian times, which are the ones that interest us" (1892: 455).

Beyond the intentions of the general exhibition and of the Junta Colombina, one must think that the images showed a variety of individuals and indigenous and mestizo groups that coexisted in Mexico in 1892. In other words, they showed the visitor a facet of the present: the subsistence of an indigenous population throughout Mexican territory. Although some states did not participate or have a presence in the collection, the group of images did give an overview of the diversity of the living indigenous population and the vestiges of the country's pre-Hispanic civilizations.

The photos brought pre-Hispanic vestiges closer to the contemporary eye and placed them at eye level, which due to their format and geographic location were inaccessible to most people and, at the same time, to hundreds of indigenous inhabitants of Mexico. Together they visually associated a pre-Hispanic past and an indigenous present, evidencing a link of continuity?

Subsequent use of the photos: objects, monuments and indigenous peoples

On the other hand, the photographs of pre-Hispanic objects and monuments and of the "indigenous races" were directly related to the efforts to promote the development of scientific studies that Mexico would promote, particularly the National Museum. For example, the chronicles of the preparations for the exhibition point out that in the process of manufacturing the 180 phototypes exhibited in Madrid, more than 600 negatives had been taken from pieces mostly housed in the museum, material that would nourish its collections and above all would serve for the research that would be gestated in this instance (Casanova, 2008; Ramírez, 2009; Rojas and Gutiérrez, 2018). Likewise, the comparison of the 1892 and 1895 catalogs shows that part of the photographic collection exhibited in the eha would be incorporated into the National Museum's collection; for example, photos of indigenous types would be moved to the anthropology section.

The records of pre-Hispanic pieces and monuments and of indigenous types would be recycled as materials for scientific study in the country. Along with them, the descriptions recorded in the 1892 catalog would be used as a source for the study of the objects, people and environments represented, a subject that would be taken up again a couple of years later in publications by the National Museum related to its collections. For example, the Catalog of the anthropology section of 1895.which was part of a set of five catalogs that were produced as part of what would become known as the xi Congress of Americanists, held in Mexico City in 1895. This document divulged the contents of the anthropology section of the National Museum, which displayed a collection of photographs of indigenous races that included many of those exhibited years earlier at the ehain addition to others that the museum had previously or subsequently collected (Rojas and Gutiérrez, 2018). There they were listed or briefly presented and the authors resorted to the descriptions that Del Paso wrote in the 1892 catalog. That is to say that in 1895 some of the photos of the eha and also the information already reported on them.

The contrast of sources also shows that not all the ethnographic photos shown in the eha were assigned to the anthropology section, but some became part of the history section. The Guía para visitar los salones de historia del Museo Nacional22 lists a group of photos of the eha located in two facistoles, thus making it possible to point out the relationship between the photos of the eha and the collections of the National Museum, namely, it contributes to the knowledge of the evolution of the photos of the eha.

This means that the photo collection -or part of it- would constitute a material to study not only the ancient pre-Hispanic civilizations, but also the living indigenous population. This use of photographic materials as a source for scientific study helps explain the inclusion of records of indigenous types in the eha. In that sense, Rojas and Gutiérrez point out that "science conceived of the indigenous as 'a subject of study that it aspired to transform'" (2018: 43-44). Mexico was showing part of the contemporary reality of the country: an aspect of the present that was problematic within the idea of the modern nation to which it aspired and which it was intended to change. But also, by exhibiting these photos, he was demonstrating that those depicted were the object of contemporary scientific study. As Aguayo says, these photos reached the eha with the objective of evidencing the scientific work being carried out in the country (2019: 107), which responded to Mexico's will to insert itself into modern practices.

Particularities of the photos sent by the states

Some contradictions that become evident when juxtaposing the images with the data in the catalogs emerge among the submissions from the states: photos that have little to do with the desired themes and temporalities and with what was requested by the Junta Colombina. For example, Yucatan, Michoacan and Jalisco sent groups of photos that showed aspects of a present reality, recalled people and spaces linked to the struggle for independence and showed architecture, technological advances and elements of modernity. All these images were accepted by the Colombian Board as part of the photo collection and were absorbed by Mexico's exhibition proposal.

In the case of Jalisco, its government submitted a series in which the pre-Hispanic and the contemporary indigenous are absent and the modern architecture of Guadalajara predominates. Included in the set were six views of the inauguration of the Central Railroad connecting the nation's capital with Guadalajara, an event that had taken place prior to the ehain 1888. The images show the protocol of nailing the last rail and the arrival of the reconnaissance and final train (Mexico Catalog, 1893: 223-227). Image 4 is a scene that shows the movement and congregation of people around the track. A panorama of the city of Guadalajara can be seen in the background and in the foreground some workers loading and placing the wooden sleepers.

In the case of Yucatán, its government only submitted photo series. In this sense, the representation of the state was constructed largely through photographs. In addition to records of archaeological remains and ethnological types, he enclosed a sample of architecture ranging from colonial to late 19th century dwellings and public buildings. xix. In other words, the photos show a pre-Hispanic Maya past, but also a contemporary facet of the state: the population of Maya, indigenous and mestizo origin, and the architectural development of Mérida.

Considerations regarding the visibility of the photos in the exhibition

The Mexico Catalog describes aspects of the exhibition design such as the furniture, the supports, their spatial location and the arrangement of the contents, concrete data that serve to reconstruct the structure of the exhibition proposal. This reconstruction of the interior spaces with the furniture, together with the mounting of the objects, helps to glimpse what the visitors' journey might have been like and how they experienced the exhibition halls in Mexico in spatial terms.

Apart from a commentary (Toda and Güell, 1893) in the Spanish press of the time that criticized the fact that the objects lacked explanatory information to know what was on display, there is little material that tells us about the visitors' experience. The importance of the knowledge of the space and the display of the objects gives us specific references to think about how the exhibits were approached and consumed, for example, how close they could get to the different types of showcases and sideboards, according to their characteristics, from where the objects could be appreciated, if they were at eye level or if they had to bend down to look and make an effort to reach higher places, and so on.

If we consider that the mounting determines the access and visibility of objects, its recovery also serves to distinguish the spatial and visual privileges that are granted to some and not to others, that is, the hierarchies between objects. Placing an object in a certain place so that it has a better visibility is related to the importance given to that object. Therefore, knowing how the objects are mounted gives clues as to what was to be emphasized in the exhibition. In this sense, the solutions in the spatial arrangement of the objects are indicators of the intentions of the exhibition proposal or of those involved in its organization.

By knowing the place and the specific way in which the photographs were displayed on the walls and different types of furniture or supports -showcases, sideboards, lecterns and paintings- and having a detailed view of their organization, it is possible to identify hierarchies, question why some groups occupied spaces with greater visibility and why series from the same place are separated, among other things.

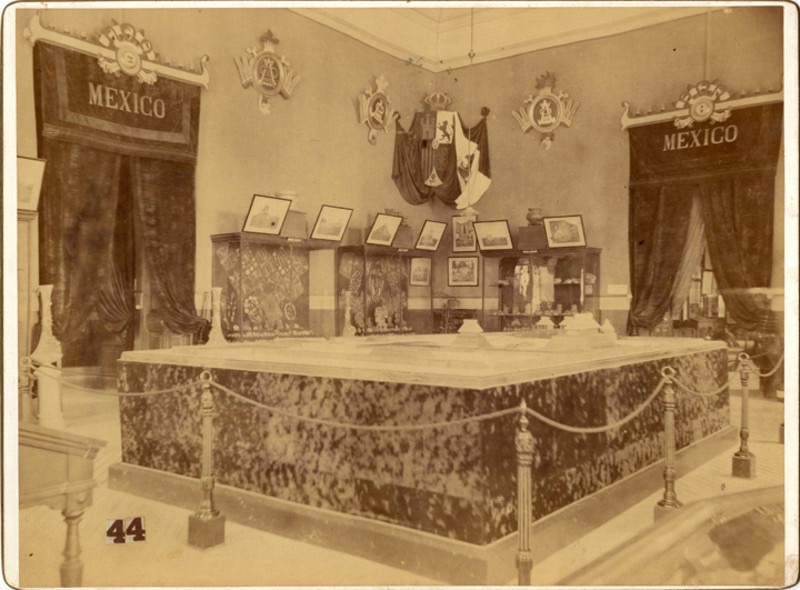

As an example, among the set of photos showing the interiors of the rooms in Mexico, there is one that shows part of the interior of the fourth room (see image 5).23 The visual information it yields coincides with the data recorded on the Mexico Catalog on the mounting of the aforementioned series of photos of "ruins of Yucatan". The fourth room displayed a set of 25 photos sent by the state government showing structures from various pre-Hispanic sites: "the most grandiose monuments of the Peninsula" (Mexico Catalog, 1893: 31). These photos were enlargements, the largest in the Mexico collection (54 x 42 cm), and had a dominant visual presence within the room. Twenty rested on the cornices of the ten showcases attached to the walls that occupied the room, that is, a pair on each piece of furniture and the remaining five hung in the few available openings in the walls. In the view of the interior this arrangement can be seen and at least nine photos can be distinguished, most of them leaning against the windows and some attached to the wall.

Unlike other groups, this series had greater visibility not only because of its dimensions, but also because of its location in the fourth room where it shared the space with seven other images; in other words, it did not compete with many other photos. This was a different case from most of the photos that were placed in the fifth room, where they competed visually with hundreds of images placed on the walls and on the six lecterns, furniture that could contain up to one hundred images each.24

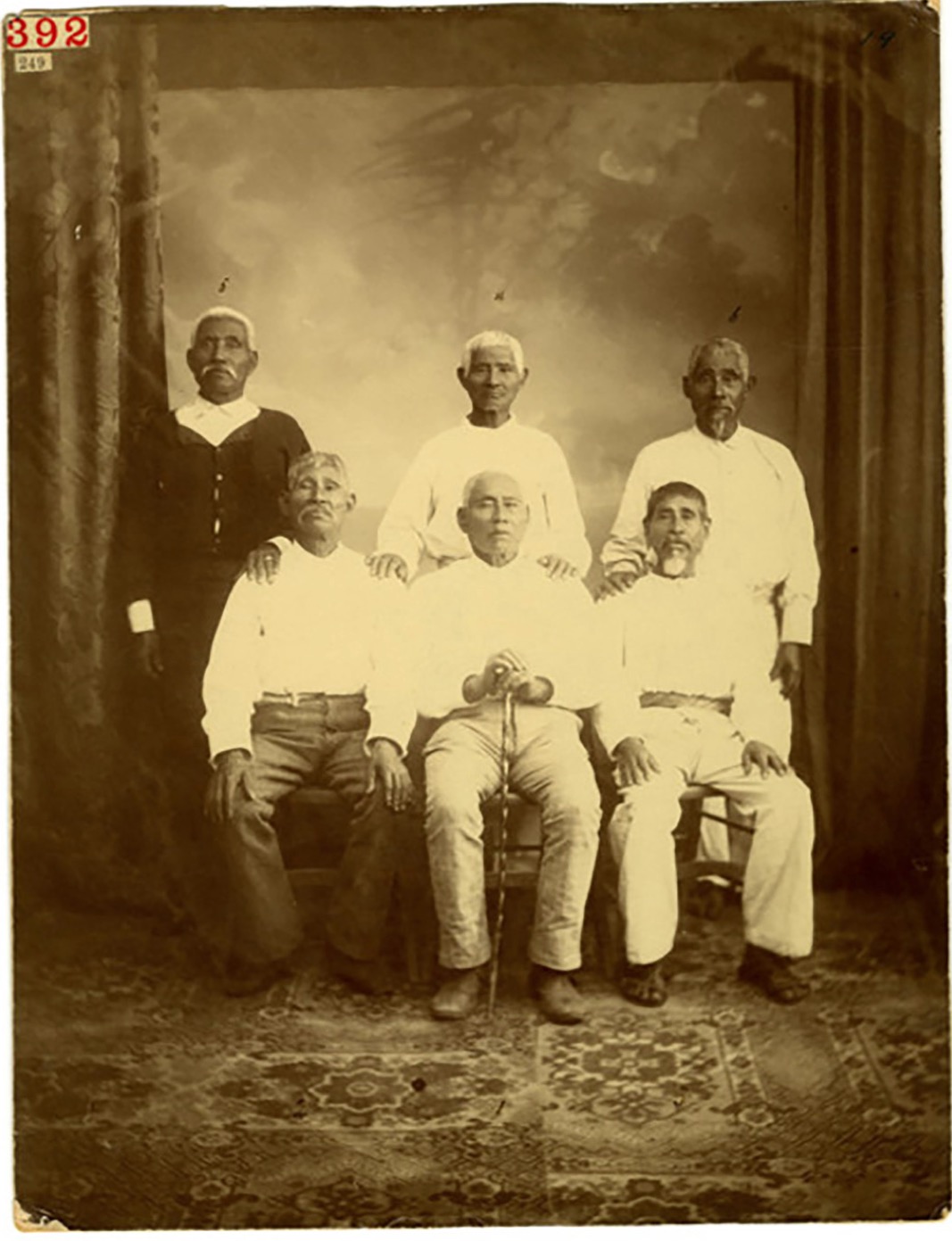

Finally, in the fourth room is a case that is exceptional in several ways, as it shows how location can reinforce a particular intention of the objects. These are three photographs of the descendants of Cosijoeza, king of Zaachila,25 which apparently formed part of a larger series of studio portraits, made in Oaxaca, of the relatives of this ruler who had to receive the Spaniards who arrived in the 20th century in Oaxaca. xvi.26 Image 6 corresponds to the second photo of the group: it is a vertical group portrait showing some of the descendants: José Antonio, Leandro, Pablo, Manuel, Eulalio and Victoriano Pérez Velasco (Mexico Catalog, 1893: 58-59).

These photos stand out among the group of "ethnological types" exhibited at the ehaare the only ones that sought to individualize the persons depicted in the image by writing their names and surnames on the back of the secondary support and entering them on the back of the secondary support. Mexico Catalog. In addition, its mounting emphasizes its uniqueness: the three 24 x 18 cm photos were grouped into a single painting hung in one of the available wall openings in the room. iv (see image 5), separated from the rest of the ethnological types, which were placed inside the facistoles in the room. v. Even if this information was not visible to visitors, it speaks of the intention of both the sender and those responsible for the montage to differentiate these images from the group of ethnological types.

Final thoughts

When approaching the photographs of Mexico, we must think of them as part of an articulated set that is integrated into a narrative proposal with specific objectives and that sought to expose the country within the framework of the American Historical Exposition of 1892. But it should also be noted that the set is made up of dozens of groups and series of photographs produced in the most diverse contexts and with very different characteristics, which deserve to be approached in their uniqueness.

The approach to Mexico's photographic collection generates and maintains two latent questions: 1) why photos of subjects that apparently escaped the wishes of the Junta Colombina and the exhibition were included; 2) what are the intentions behind the different groups of photos that make up the collection. The photographic collection that Mexico presented in Madrid contains such varied, not to say disparate, material that, in addition to considering it as a whole, it merits a review of the different groups of photos separately. Here I have mentioned just a few examples.

Considering that this dossier is concerned with the possibilities of the image, its relationship with other types of sources and its use for social research, I addressed aspects arising from a study that began and ended with photographic images. Rather than delving into the results of an investigation that sought to approach and analyze a part of the presence and representation of the country in an international exhibition, I have tried to uncover some written and visual materials, as well as ways of proceeding to build the photographic corpus and the scenarios found along the way.

Bibliography

Aguayo, Fernando (2019). “Los significados de la fotografía de ‘naturales mexicanos’ en la Exposición Histórico-Americana de 1892”, Dimensión Antropológica, inah, año 26, vol. 75, pp. 94-132.

— (coord.) (2019a). Fotógrafos extranjeros, mujeres mexicanas, siglo xix. Ciudad de México: Instituto Mora. Recuperado de: https://mora.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1018/472/1/Fotografo-sextranjeros.epub

— (2008). “Imagen, fotografía y productores”, Secuencia. Revista de Historia y Ciencias Sociales. Ciudad de México: Instituto Mora, núm. 71, pp. 133-187.

“Cablegramas” (1892). El Siglo Diez y Nueve, México, 2 de noviembre, p. 3.

Casanova, Rosa (2008). “La fotografía en el Museo Nacional y la expedición científica de Cempoala”, Dimensión Antropológica, inah, año 15, vol. 42, pp. 55-92.

Catálogo de la sección de México (1892). T. i. Madrid: Establecimiento Tipográfico Sucesores de Rivadeneyra/Impresores de la Real Casa.

Catálogo de la sección de México (1893). T. ii. Madrid: Establecimiento Tipográfico Sucesores de Rivadeneyra/Impresores de la Real Casa.

Catálogo general de la Exposición Histórico-Americana de Madrid 1892 (1893). 2 tomos (i and iii). Madrid: Establecimiento Tipográfico Sucesores de Rivadeneyra/Impresores de la Real Casa.

Circular de la Junta Colombina dirigida a los gobernadores de los estados (1891). Archivo General del Estado de Yucatán (agey). Fondo Ejecutivo 1886-1892, Sección Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán, serie Gobernación, caja 442, vol. 392, exp.18, f. 1.

Domínguez González, Marisol (2023). “Cómo llevar Yucatán a cuestas. Fotografías del estado de Yucatán en la Exposición Histórico-Americana de Madrid en 1892”. Tesis de maestría. Mérida: ciesas.

Galindo y Villa, Jesús (1899). Guía para visitar los salones de historia del Museo Nacional (3ª ed.). México: Imprenta del Museo Nacional.

— (1892). “Exposición Histórico-Americana de Madrid de 1892. Nota relativa a la sección de la República Mexicana”, en Memorias de la Sociedad Científica “Antonio Alzate”, publicadas bajo la dirección de Rafael Aguilar y Santillán, T. vi. México: Imprenta del Gobierno Federal en el Ex-Arzobispado, pp. 300-323.

“La Exposición Histórico Americana de Madrid” (1893). El Monitor Republicano, 8 de julio, pp. 1-2.

Mendoza, Mayra (2012). “Interiores para legitimar un pasado glorioso: Exposición Histórico-Americana de 1892”, Alquimia, sinafo/inah, año 15, núm. 45, pp. 8-21.

Mélida Alinari, José Ramón (1892). “La Exposición Histórico-Americana. México i“, La Ilustración española y americana, núm. xlviii, 30 de diciembre, pp. 455-458.

Muñoz B., Carmen Cecilia (2013). “Imaginarios nacionales en la Exposición Histórico-Americana de Madrid, 1892. Hispanismo y pasado prehispánico”, Revista Iberoamericana, xiii, núm. 50, pp. 101-118.

— y Paula Revenga Domínguez (2020). “Tras bambalinas: museografía y proyección de imaginarios nacionales en las Exposiciones Históricas (Madrid 1892)”, Historia y Espacio, vol.16, núm. 54, pp. 103-136.

Plano de la Exposición Histórico-Americana (1892). Madrid: Fernández Peñas/Litografía del Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico. Recuperado de: https://bibliotecavirtualmadrid.comunidad.madrid/bvmadrid_publicacion/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?presentacion=pagina&path=1000150, consultado el 20 de junio de 2024.

Ramírez Losada, Deni (2009) “La Exposición Histórico-Americana de Madrid de 1892 y la ¿ausencia? de México”, Revista de Indias, vol. lxix, núm. 246, pp. 273-306.

Rodrigo del Blanco, Javier (2018). “La preparación de las Exposiciones Históricas”, en Javier Rodrigo del Blanco (coord. y ed.). Las Exposiciones Históricas de 1892. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, pp. 35-84.

— (2017). “La organización de la Exposición Histórico-Natural y Etnográfica”, en Javier Rodrigo del Blanco (ed.). La Exposición Histórico-Natural y Etnográfica de 1893. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, pp. 53-73.

Rodríguez, Georgina (1998). “Recobrando la presencia. Fotografía indigenista mexicana en la Exposición Histórico-Americana de 1892”, Cuicuilco. Revista de la Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia. México: enah, vol. 5, núm. 13, pp. 123-144.

Rojas Rabiela, Teresa e Ignacio Gutiérrez (eds.) (2018). Edición facsimilar conmemorativa del Catálogo de la colección de antropología del Museo Nacional. Alfonso L. Herrera y Ricardo E. Cicero (1895). Ciudad de México: Secretaría de Cultura/inah/ciesas.

Suplemento-guía de las Exposiciones Históricas (1892), El Día, 10 de noviembre, núm. 4508. Recuperado de https://hemerotecadigital.bne.es/hd/es/viewer?id=b41fc752-9fb4-4fc7-b76c-6e6fa3b0a0e0, consultado el 8 julio de 2024.

Toda y Güell, Eduardo (1893). “Exposición Americana en Madrid. Las salas de México”, La Ilustración Artística, núm. 580, 6 de febrero, pp. 90-92.

Marisol Domínguez González holds a degree in Art History (Universidad de las Américas, Puebla) and a master's degree in History (Universidad de las Américas, Puebla) and a master's degree in History (Universidad de las Américas, Puebla).ciesas). He has worked as a curator, researcher, translator and teacher. He has collaborated with the Fototeca Pedro Guerra (wow) and has designed exhibitions for the Museo Regional de Antropología e Historia, Palacio Cantón and the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya in Mérida. His research has focused on the construction of visualities and the history of photography in Yucatán.