Noises and silences in the migrant waiting: sound environments and racialization of listening in the Haitian community in Tapachula.

- Mónica Bayuelo García

- ― see biodata

Noises and silences in the migrant waiting: sound environments and racialization of listening in the Haitian community in Tapachula.

Receipt: May 31, 2023

Acceptance: November 4, 2023

Abstract

In light of the fact that listening is, in its most primordial sense, a form of social recognition, this article proposes a reflection of the process of sound and listening on the symbolic practices that strengthen a silencing towards and by migrant communities as policies of rejection. It explores the categories of silence, noise and racial appreciations from which the Haitian community in Tapachula, a city of forced waiting, is perceived by institutional actors and humanitarian organizations, manifesting diverse sentiments.

Keywords: listening, mexican southern border, Haitian migration, racialization, noise, silence, Tapachula

sounds and silences in the migrant wait: soundscapes and the racialization of hearing in the haitian community in tapachula

In its most primordial sense, listening is a form of social recognition. Drawing on this idea, this article reflects on sound, hearing, and the symbolic practices at the core of anti-immigration policies that reinforce silence toward and by immigrant communities. This article focuses on the Haitian community in Tapachula, Mexico, a city where refugees are forced to wait. It explores the categories of silence, noise, and racial beliefs about these immigrants -as well as the myriad feelings associated with them- on the part of institutional actors and humanitarian organizations.

Keywords: Haitian immigration, sound, silence, racialization, listening, Tapachula, Guatemala-Mexico border.

the silence

more heartbreaking than a simun of azagayas

more roaring than a cyclone of wild beasts

and howling

rises

requests

revenge and punishment

tidal wave of pus and lava

on the felony of the world

and the eardrum of the sky burst under my fist

of justice

Ebony wood, Jaques Roumain

Introduction

The rumbling on the afternoon of January 12, 2010, caused by the 7.3 earthquake that shook Port-au-Prince, Haiti, showed that the origins of the catastrophe were the exclusion and poverty in which that part of the Caribbean island had been living for a long time. The future that would befall its inhabitants was still in doubt and the only certainty at that time was that a new era was beginning in its diaspora.

The complex history of this country has delineated great migratory waves in which the rejection that this population has encountered in the territories to which it has moved has been present. Perhaps we should briefly go back to the eighteenth century, a time when black slaves rose up against slaveholders and French colonial authorities. The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) then confronted two great yokes: French colonization and slavery, and this extraordinary news spread to neighboring territories, for "the self-liberation of black slaves in Haiti stimulated the imagination and triggered a revolution of consciences" (Ferrer, 2003: 675), which could compromise European interests in the Caribbean. In Cuba, for example, the "fear of Haiti" was essentialized in the "fear of the Negro" (Ferrer, 2003: 676), ignoring the political force of what was the first independence struggle in America. Even then, to minimize that portentous social process symbolized a kind of silencing against those revolutionaries.

Years later, U.S. economic domination in Cuba and the Dominican Republic (1915-1934) through the cultivation of sugarcane in those lands, but with labor from Haiti, reconfigured the mobility of this population to neighboring lands (Coulange, 2018). At that time and as a tense consequence of this intervention, violent practices arose in the Dominican Republic against the Haitian population; for example, the so-called "domination of the border" during the dictatorial era of General Rafael Leónidas Trujillo became an ethnic genocide sheltered under the classist and racial ideology that the migrant "of purely African race" did not represent "any ethnic incentive", thus differentiating him from those "desirable" Haitians: "of selection, the one that forms the social, intellectual and economic elite of the neighboring people. That type does not worry us, because it does not create difficulties for us; that type does not emigrate" (Peña Battle, 1942).

One of the most violent episodes that are part of the memory of the Haitian people during those times is the Parsley Massacre, so called because of the linguistic test ordered by Trujillo, in which, to distinguish Haitians from Dominicans trying to cross the border between one side and the other of the island of Hispaniola, they were required to pronounce the word "parsley". The Haitians' phonological apparatus made it impossible for them to pronounce the /R/, because in their language, Creole, this sound is softer, so they were easily detected and executed immediately.

In 1957, the government of François Duvalier began with the Cold War as a backdrop. Supported by the U.S. intention to contain the influence of communism in the Caribbean, together with the expansion of the paramilitary group the Tonton MacouteThe "bogeymen" created the ideal environment for the dictatorship of Duvalier and his successor, Jean-Claude Duvalier, to take hold, strengthening the political, economic and social instability of Haiti, thus promoting the second great period of migration of Haitians to Canada, the United States, France, other Caribbean islands or Mexico (Louidor, 2020: 53).

The third major period of Haitian migration took place after the 2010 earthquake, this time to South America, especially to countries such as Brazil, Chile and Ecuador; the latter two, by not requesting visas or other entry requirements, became the main destinations of this mobilization until the migratory flow seeking to enter these States exceeded expectations, making regularization conditions more complex and noting the prevalence of social and cultural stigmas that have hindered the dignified settlement of this population (Louidor, 2020: 54). In this sense, it must also be said that, although in principle these countries welcomed Haitians in solidarity based on international humanitarian agreements, there were also practices far from protection and closer to the absence of human rights. An example of this is the stay at the border of Tibatinga, Brazil, where more than three thousand Haitians were stranded for two years, until the government decided to issue humanitarian visas (Louidor, 2020: 58).

The particularities of this mobility can be better understood under the auspices of the category known as "Transnational Dispersion of Vulnerability" (dtv); this refers to the "reiteration of circumstances of precariousness throughout the migration cycle as conditions similar to those faced by vulnerable populations in their societies of origin" (Fresneda, 2023: 672); that is, the history of that country, with dictatorships, coups d'état, terrorism, military interventions and environmental crises, caused an imbalance in public policies that resulted in inequitable access to opportunity structures (such as educational precariousness), added to the large population growth of the time and the fragility of investment in the agricultural sector (Fresneda, 2023: 678), factors that facilitated the increase in outward displacements, finding similar circumstances in the destination cities and on their way to them, but now with one more disadvantage: the status of migrant.

This history of mobility, vulnerability and rejection, first to neighboring lands in the Caribbean and later to the Southern Cone, has forced this community to renew its routes to the north of the American continent, crossing vast territories and surviving the most adverse situations hidden in the depths of Latin America until reaching Mexican territory.

Until a couple of years ago, the urban spaces south of the border in Mexico, traveled by migrants with the intention of reaching the north of the continent, were recognized as transit cities because their stay was brief and the gait and voices of their passersby were also fleeting. However, this has given way to a stagnation in this country that has transformed displacement into uncertainty and waiting due to causes such as the intensification of policies1 The main reasons for this are: the lack of legal status, the lack of clarity in the socialization of current policies and processes of action that would allow those interested to obtain some type of migratory regularization, either for the purpose of traveling with fewer risks during the journey, or to settle in a Mexican city, to be employed and to have access to social welfare structures.

Historically, Tapachula, located on Mexico's southern border, has been a host city for communities coming from other latitudes: during the second half of the 20th century, Tapachula was one of the most important cities in Mexico. xix and the beginning of the xx saw the arrival of people from Germany, Lebanon, Japan and China, who, driven to travel to Mexico after the Porfirian promotion that "exalted the benefits of migration in Mexico through its consulates in the United States and Europe" (Avella, 2000: 447) settled in the city and its surroundings. Soon after, the mobilizations of the Central American population also began to gain visibility, becoming one of the most important migratory flows in this place so far. In more recent years, the city has witnessed the passage of Central American caravans, the Haitian and Venezuelan exodus and lately has witnessed the increase of people coming from Cuba and different African countries.

These presences have turned Tapachula into a space as complex as contradictory not only because, being the first point of entry, it receives large population flows of very different origins, but also because political interests converge there that place Mexico as a country that responds to the restrictive and containment demands of the United States, but that in the public discourse shows solidarity, empathy and attachment to the humanitarian ideal. In this space, several purposes and presences linked to migration interact: those of people in mobility, those directly related to the migration industry (such as coyotes or renters), as well as migration authorities, politicians and the local population.

Not all mobile communities are received with the same enthusiasm in this Mexican city. A similar situation was identified by Alejandro Canales (2019) in the case of Haitian migrants in Santiago de Chile; the author argues that there is a perceptible distinction in the access to migratory regularization, health, education, labor market and even in the area of residence and "that puts on the table the debate of the social construction of racism and ethnic discrimination2 based on the migratory status and national origin of the immigrants" (Tijoux, 2016 in Canales, 2019: 57). In this way, this article explores the way in which ethnicity and class of Haitian people in Tapachula intervene in the exercise of their powers, in how they are perceived by civil society, regularization institutions and international humanitarian assistance organizations, and how these differences produce practices that replicate a cultural stigma about the perception of listening to the other as noisy, who is not worthy of listening and who is, therefore, silenced.

Despite the fact that human mobility is made possible above all through the body and the existence of the body in a space in which sonorities and their repercussions are essential in the interrelations of those who cohabit there and, although they are often ignored, especially in a population whose sensitivity has been pushed to the background, the significance of these sonorities evidences the existence of travelers in territories in which they are considered strangers. Since "the sensory is political" (Hamilakis, 2015: 41), to abound in this field, particularly from sound studies, is also to break down ideas that generalize "abuses against migrants", as it allows to answer what they consist of and what their procedures are, in addition to making notorious the tensions and solidarities between various collectives that often involuntarily coexist in a territory.

To be interested in this is to recognize that, given our intrinsic sensoriality, we can use our senses systematically to reflect on how certain corporealities, and even more, certain sound and listening processes are perceived in specific contexts: waiting and uncertainty, as in the case presented here. It also allows us to learn about human mobility through the experience of its protagonists, narrated from their own sensory paradigms and/or the transformation of these paradigms as they walk and, as we do so, we are introducing ourselves to studies of the perception of the identity of migrant communities.

Thus, the main purpose of this article is to explore the processes of sound and listening, or aurality, of the Haitian community in Tapachula through notions of silence and noise, how it is crossed by the perception of ethnic and socio-cultural factors and the way it is perceptible through the so-called sound marks (soundmarksThe sounds characteristic of a community), evident in the public spaces of this city.

We understand the term "aurality" as that:

set of values, concepts and paths of meaning that are performativized in listening, and at the same time, determine the ways in which the sound dimension, in each moment and place, becomes significant for a subject or intersubjective fabric (Savasta, 2020).

Aurality then is a process that involves, simultaneously, sound emissions and listening, that is, reception, the ways in which these sound emissions are perceived and what they provoke in us (Domínguez, 2011; Bieletto, 2018) beyond the biological process, also in its sociocultural dimension.

More than answering what the migrant waiting sounds like in this city, the questions that guide this reflection are the following: what are the elements of segregation in this border space in terms of sound and listening, is this migrant listening homogeneous for all the populations that converge there, what other factors intervene in this process? To accommodate the above questions, this work is situated in what has been called the "sensory turn in the social sciences" (Sabido, 2019), which warns about the relevance of the senses, perception and the body as fundamental axes to create knowledge and make sense of the world by understanding the affects that sustain it. Thus, this work is positioned between the convergence of sensory studies, especially sound studies, taking into consideration the notion of noise and racialization of listening (Domínguez, 2011; Bieletto, 2018), contrasting them with the field of research on human mobility.

We understand the notion of noise not only in its material dimension as a sound quality, but as a category of listening (García, 2022), that is, as a construction of perception: "it is factors such as taste, mood or the time and place of appearance of a sound that determine its degree of negativity" (Domínguez, 2014: 107), which, by involving more than one subject, sometimes becomes tensions or conflicts in which underlies the relationship between noise, power, space and territory (Domínguez, 2011: 36).

In the southern border region of Mexico, the presence of certain communities in mobility can become tensions within a territory, not precisely because they are within the same sound situation, sharing the same acoustic vibrations in a given space, but in these tensions also come into play the very interpretation of territory, certain migratory policies and even the racialization of bodies, which, being alien to the subject with "colonized subjectivities" (Bieletto, 2018: 163), are transformed into a social disregard traversed, in the case presented here, by race and by national and international migratory policies, as an underlying factor in the willingness to listen.

This work attempts to contribute to the conjugation of sound studies in specific contexts that involve restrictive mobility policies, cultural stigmas, but also bodies and affects, incorporating new elements in the social analysis of listening.

Methodological considerations

For the elaboration of the following, a qualitative methodology was used with the following information gathering strategies, of course, all in Tapachula: from May 2021 to February 2022, and due to an employment within international humanitarian aid organizations, participant observation and listening were conducted in these closed spaces, but also in public places, such as food establishments, in the municipal market and in open plazas, namely Miguel Hidalgo, Benito Juárez and Bicentenario parks, located in the center of the city, with the purpose of knowing the context of interaction in these places. I take up the notion of "participant listening" by Victoria Polti (2011) understood as "the theoretical-methodological tool that allows addressing sound routines, sound events and discourses through the act of hearing and producing sounds as a practice shared by the subjects and the researcher" (Polti, 2011: 10). The audio samples and photographs that accompany this article were taken, in principle, during those tours and, later on, the small audiovisual archive shared here was nourished in many subsequent visits to the city in the first half of 2023.3

Likewise, at the beginning of 2022, a sound mapping focus group was held. Some of the fragments of conversations cited here are taken from these meetings. This ethnographic collection technique consists of gathering a small number of members (six people in this issue) who share certain characteristics with the rest of the group, in this case migrants who live in Tapachula and whose experience favored the discussion about their perception of sound, both in their journey and in this border city through cartographic representations. These maps serve as a methodological and also epistemological tool, since they allow access to the authors' own narratives of these creations, facilitating emotional and subjective knowledge, since in them feelings, thoughts and experiences can be expressed, that is, "they reproduce life in a territory" (Suárez-Cabrera, 2015: 635-639).

The waiting, frustration and uncertainty that the migratory context brings with it are perceptible in the migrant population of Tapachula through attention to the sound and symbolic environment created there and the experiential cartographic record of the participants in these focus groups.

The order of this exhibition is as follows: first, the modes of silencing during the journey of the Haitian community to Mexico are explored. Later, some sound environments of Tapachula are explored when this diaspora converged with other migrant communities and with the local population that received them, in order to show how the perception of Haitians was interpreted as noisy by migration regularization institutions and the media. The racial element is brought to the table as a fundamental factor for the aural and, therefore, socioeconomic and cultural segregation of this Caribbean population, as well as the power of silence as a strategic form of resistance.

Preamble on the journey: the habit of keeping silent

For foreigners traveling from distant lands and whose passports are not welcome in all airports, the routes and transports are diversified and can become a risk to their integrity, barely counteracting it by being silent witnesses of the most atrocious acts of dehumanization. This has been the case with Haitian people who, after the 2010 earthquake in their country, were welcomed by Chile and Brazil, although by 2018 large mobilizations began again due to the difficulty of renewing work visas, which limited the obtaining of legal documents that would guarantee social security and access to development. This suggests that silencing is also reproduced in the political order by the condition of "undocumented", experienced in many societies where they have tried to settle.

Not all Haitians were born in Haiti, many of them were born in the Caribbean or South America, they learned two, three or more languages from a very young age and maintain the Creole language, which resists from the intimate and the personal during the long displacements.

Spanish is a familiar language for many of the Haitians who have arrived on Mexico's southern border. Some acknowledge an original lack of interest in learning it during their schooling. So said B., who at the time found it boring and even a bit impractical, as his parents, and the parents of his classmates, urged them to seek to learn English or French, which, they felt, were more beneficial languages in the event of going to the United States or Canada.

author, March 2022.

To reach the so-called North America, transfers from South America are usually made by bus without major mishaps, but there is a point on the way to reach the center of the continent that represents a terrible episode in the memory of people who have crossed it: the Darien jungle, famous for having impressed the experience of those who have managed to get out of there alive: "but it is a bit of a tough experience. I saw things I had never seen in my life. But it was also an experience. I always avoid talking about it because it is terrible. kd, March, 2022).

All kinds of abuses have been witnessed in that territory. B., with her husband and daughter, undertook this journey after four years of living in Chile and after being denied permanent residency. During this journey, she managed to get out safely from a security post, where presumably women are sexually abused, thanks to a friend of hers who had crossed previously and who warned her not to wipe off the mud that irremediably imprints itself on her clothes up in the mountains. On the way, she herself repeated, loudly, the recommendation with her companions. Leaving the jungle, she and her family took some time at a refuge in Panama to regain strength and continue on the road to Costa Rica and Nicaragua by bus.

It was in Guatemala that the restrictions began. Upon leaving the bus terminal, she and her family took a cab that took them to a trailer in which they would travel for eight hours locked in a wagon at high speed and which, for two hundred and fifty dollars, transported them to Tecún Umán (Guatemala) with the purpose of crossing the Suchiate River (Mexico) during the early hours of the morning. The scenario through which they travel to reach Mexico is very clandestine and the general recommendation is that they should not be seen:

You have to pretend that you are normal, that it is not the first time you cross. From Guatemala you have to cross in a trailer, and there you don't have to make noise so that migration doesn't see you, for seven or eight hours. It is horrible because inside it is black, you can't see anything, and there anything can happen, and they ran so fast, fast and you move up like a sack, you have nothing to hold on to and you have to stay on the floor, there, quietly (B., personal communication, March, 2022).

In response to the meanings related to the violence experienced and the multiple losses, silence and self-censorship emerge in migrants as a protection against threats and stigmatization:

In their places of origin they learned that keeping quiet allowed them to go unnoticed and protect themselves from violent threats; in the city they evidence that not telling their story, not naming themselves as displaced enables them to protect themselves from rejection, from stigmatization and to begin to regain control of their privacy and their lives (Díaz, Molina and Marín, 2014: 19).

Silence in the migrant population is common and varied. Sometimes it is exercised on them as a practice of social annulment, but when it is deliberately employed by people in mobility, it becomes a strategy of protection against the hostility to which they are exposed, and which, by seeking to go unnoticed, will free them, in the best of cases, from hostilities, exclusion or deportation.

Recorded by the author, March 2022.

In the preceding audio, B. narrates the difference between nationalities and its implications in the international migration policies applied in the jungle region linking Central and South America: if people from other countries are detained, they will most likely be deported to any other country, while, in the case of Haitians, they will be returned to Hispaniola, reason enough to try to go unnoticed. This strategy is common among people in mobility and is related to previous transit experience. They know that immigration authorities have the power to detain foreigners whose legal stay in the country has not been regularized and deport them; like B., thousands of people no longer come from Haiti, but from the Southern Cone: nothing awaits them on the island, besides the fact that being deported would very possibly imply having to make the journey through the jungle again, a scenario they cannot afford.

Waiting sound environments.

The Haitian Diaspora in Tapachula

According to the notion of the word, those who expect stay in a place in the hope that something, usually favorable, will happen, with the confidence that it will (demThis has not been the case for all the regularization requests that Haitian nationals have made to the corresponding authorities.

In 2021, their welcome turned out to be chaotic for this small city, which, although it has historically seen thousands of people passing through, had never received so many to stay and lacks dignified conditions to offer to this population; Thus, the main squares of this town became shelters through a forced appropriation of these spaces to carry out activities that in other circumstances would belong to the private sphere, such as spending the night, feeding, cleaning and raising children, that is to say, there was an occupation of public space as the only option to stay, and at the same time a cancellation of intimacy.

From the thought of Judith Butler (2018) and Michel Agier (2015), marginal corporealities confirm their right to the city as they exercise their freedom of expression through loud protests, meetings in spaces in which they claim justice and recognition, as well as the construction of habitats. Let us consider other ways of being, listening and demonstrating in these places when one has an unfavorable political condition, such as that of migrants stranded in these cities, which, according to their own perception, "traps" them through the establishment of politics of fatigue.4 The Mexican authorities are trying to stop them from moving northward and remain in the bottleneck that many border cities in Mexico have become.

2023.

To disrupt The arrival of these migratory flows also transformed their sonorities, incorporating their own aural habits to the soundtrack of the public spaces shared with the local population, which would later account for the processes of interaction. In the above audio, recorded on Museum Day (May 18) in the Benito Juarez Park as a great sonorous space, we perceive the dynamics that took place there between communities and languages, but also with other species, for example, the birds whose home resides in the few trees left by the renovations in the park, or with other objects, such as the bells that announce the next mass in the church of San Agustin, next to where this Haitian vintage is located.

The use of the term sound mark (or soundmark in English) comes from the soundscapes studies to refer to the characteristic sound of a community whose uniqueness is distinctive among the other sounds that coexist there. In spaces such as Benito Juárez Park, listening to Creole stands out as a sound mark that differentiates the interactions of this population with other languages. The peculiar accent of Caribbean people when they speak Spanish adds to the specificity of this sonorous space and, as a linguistic memory, is a record of long stays in other territories. In addition to the convergent languages, the rhythm of the music they share with those who pass by, shows the ways of coping with the waiting times. During one of the tours to this site, it was a surprise to hear that the music played there is from Brazil or, well, from distant places such as Nigeria: "I was surprised to hear that the music is from Brazil or from Nigeria.Everybody needs a special someone/ wey go dey to make you smile/ wey go drive all the tears from your eye/ everybody needs that special love/ wey go always hold your hands/ wey go there with you through the end" (Singah, Nigerian singer, 2021). These listenings resonate with other migrant communities gathered in public space, the African community, for example, which has slowly increased its flows into the city and with whom they share ethnicity and, recently, prolonged stagnation in Tapachula. Many of the members of the Haitian community have spent long periods in Brazil, perhaps that is why listening to music in Portuguese is familiar to them, in a process of constant updating to their socio-cultural capital.

The linguistic skills developed during their long stays and travels throughout the continent, together with the need to stimulate their economy, have resulted in the ability to sell by making rhymes in Spanish, audible in informal trade activities; at first in the sale of technological devices, such as speakers and headphones, chips and telephone articles, and as time went by, Haitian gastronomy: vegetables or rice with fried chicken, hygiene articles, new tennis shoes, kitchen utensils or soft drinks.

Recording by Author, March, 2022.

At the beginning, the presence of these new sonorities was mostly perceptible at points where humanitarian assistance services were offered. By the end of 2021, the most important meeting place was the Miguel Hidalgo Central Park, which they began to inhabit as soon as they arrived and, later, due to the cancellation of its public use because of the installation of an artistic work that we will talk about later, the Benito Juarez square, located in front of the park from where they were excluded and where since then until now they have installed a vendimia.

by Author, May, 2023.

Many of these vendors are still stranded in the city waiting for a resolution to their request for refuge: "without work there is no money, and without money there is nothing to do but sit in the shade and wait" (B., personal communication, 2021).

Bicentennial. Recording by Author, June 2023.

Noise and racialization of listening

The experience of communities' stay in cities depends a lot on the reception of the usual inhabitants, as well as of other migrant populations converging for the same purpose of leaving or settling down, and this admission is created from the temporality of their stay, the conditions of occupation of the space, their migratory regularization and also their purchasing power. For example, for carriers, the arrival of these populations has increased the good reception towards them because it is parallel to the income they generate by using these private urban mobility services, even if the communication between them is crossed by mobile devices, such as online translators. In this perception of the otherrace and class intervene as essential elements in whether or not they are welcome to spend more time sharing the city.

[...] I was able to observe divided postures regarding the presence of these [Afro-descendant] populations, as bodily visibility and blackness had an impact. Although it was not very common, verbal aggressions, discriminatory postures and attitudes of racism and xenophobia were focused towards African people, but not towards Asians, because many city dwellers were even unaware of their transit through the city, this because "their skin tone does not attract attention". [...] The exoticization of the other somehow becomes something normal because people considered the "black" as different, since it is "rare to see him walking around the city", the worrying thing is when the sense of discrimination is added to the sense of a potential danger, and criminalized because of the racial issue (Cinta, 2020: 94).

This forced foreign habitation served to recognize the administrative incapacity of the authorities of Tapachula with respect to the provision of the most basic humanitarian services, such as shelter, understood in its strictest sense: that of protecting those to whom it is offered from the inclemencies. In an accumulation of practices of social deafness, by ignoring the international security requests of those interested in regularizing their migratory situation, delaying the procedures that would grant access to health services, education or work; limiting support to the shelters in the city, which have always been saturated, or in more serious cases, detaining them by using security forces (National Guard, the army and the navy) gave rise to the perception of migrants as intruders, as those dispossessed of their private space, of their privacy, and segregated them from the rest of the population, This gave rise to xenophobic practices by the media, replicated by institutions of migratory regularization, which labeled the occupants as dirty and noisy.

If we make a deeper reading towards the obvious, as Yannis Hamilakis suggests, migration is a material and sensorial matter. So much so that at borders the detection of people traveling without migratory regularization consists of aspects such as color, smell or the pronunciation of their accent (2015: 41). Although it is true that the stigma of intruder falls on many foreign people, this is even more notorious in the Haitian population because of the phenotype that identifies them as outsiders almost immediately, coupled with their language and emphasized by their class, the latter evidenced in the "loss of the ability to mobilize resources and the erosion of the ability to maintain material exchange" (Fresneda, 2023: 675). On the first aspect, it is not superfluous to bring to account the association between the perception of noise as a disturbance typical of barbarisms, as opposed to qualities granted to silence as the harmony of civilization (Bieletto, 2018: 168).

Especially, the linguistic issue is a reason that tries, without succeeding, to justify this disregard with which they have been received, arguing the lack of communication and understanding with the speakers of their native Haitian Creole; in light of the fact that it is difficult to communicate truthful and direct information about processes, purposes and requirements about the legal stay in Mexico, omissions and strong violations of the rights of this community are generated. From this, pejorative labels are attached to them, which, more than showing cultural mismatches, confirm the racialization of migration in Mexico and, even more, of the racialization of the sound-listening process (Bieletto, 2018) of the Haitian diaspora in funnel cities, such as Tapachula.

What about those people whose democratic demands are not heard, those people who speak a language that sounds like noise to the ears of others, those whose language is a kind of noise for which there is no apparent translation into the democratic structures in place? Is it indeed noise, or is it a demand? Does it come from people outside democracy? [...] They are not always recognizable as subjects. And their language is not always recognizable as language. They have become the noise at the gates of parliament, at the gates of established democratic institutions, and since the sounds they emit cannot be granted the category of language, nor can they be inscribed in the lexicon of political demands available to us, what they make is noise: they are the noise of democracy, of democracy from outside, of that which demands an opening of institutions for those who have not yet been recognized as capable of expressing themselves, as possessors of political will, as deserving of representation (Butler, 2020: 72).

We have then that the cultural practices of this population in in/mobility are interpreted as noisy, especially by the media and promoted by policies and executed by migration regularization institutions, because they are based on the perception of intrusion that accompanies them during their journeys. "Irritating, disturbing, dirty, threatening and barbaric" are some adjectives with which characteristics are attributed to noise, but it is also common to find them in the media when referring to these communities. In these appraisals, one reads the "effect on the mood" that this phenomenon can cause on others; that is, it is a sound-listening process crossed by perception, the same that will determine whether some sound will preferably be heard or not, according to cultural, historical, epistemological, territorial situations (Bieletto, 2018: 162) and, in the case of the Haitian diaspora, racial ones.

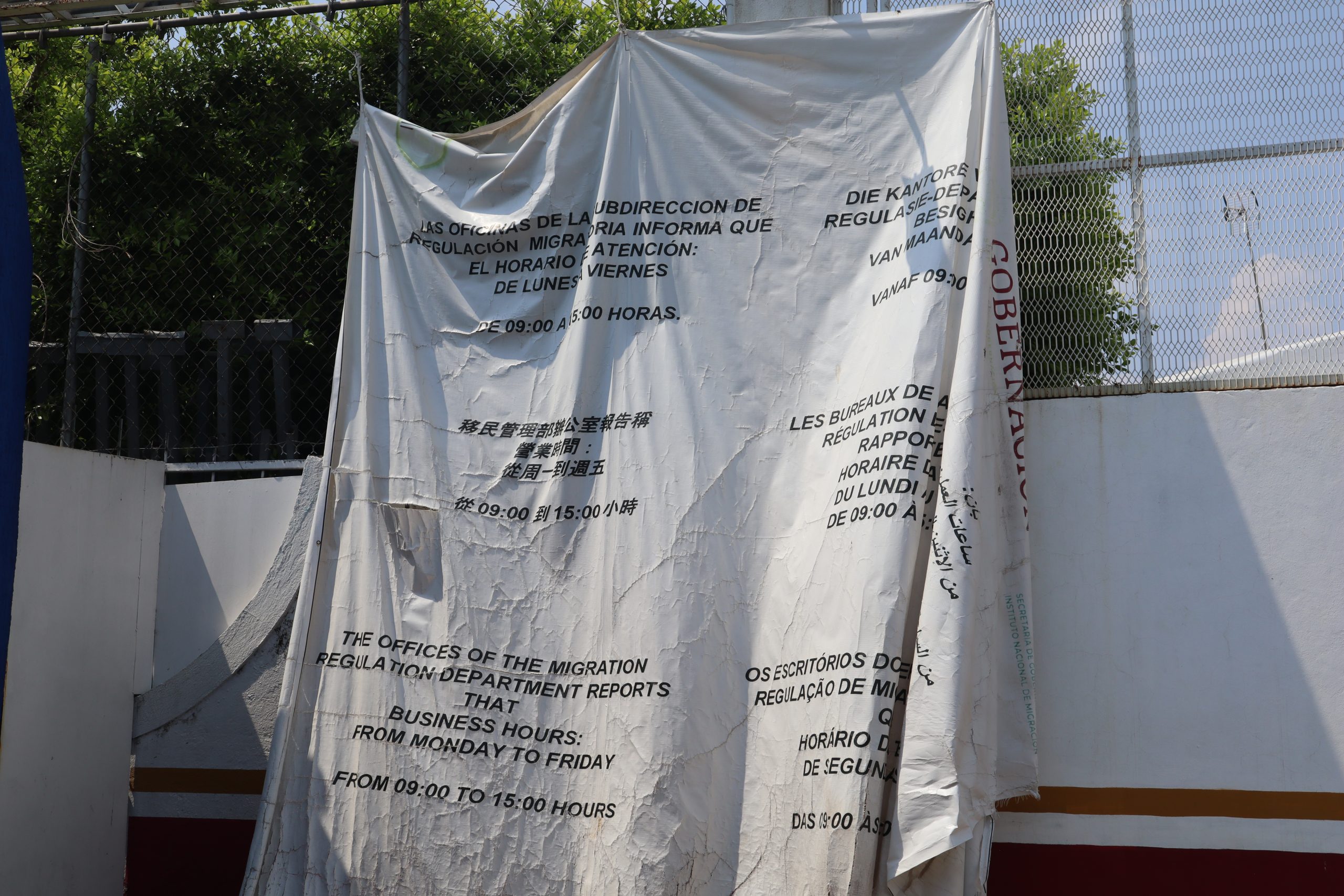

Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid.

This is how the sound space becomes a political terrain by becoming a scenario of rivalries, in which one of the parties imposes its sound sphere and the other is subdued through what it considers a violation of its own sphere. (It emerges then) a new field of coexistence and social conflict around noise, where what is disputed is the right to do in a place that is considered one's own (Domínguez, 2011: 36).

Silencing: between exclusion and resistance

This consideration of what is one's own against what is foreign, as well as the impetus to avoid any disturbance of the known world, has much to do with the concept of citizenship and the exercise of rights that this legal category grants: if "belonging" to a nation state would "facilitate" having a voice with sufficient strength and ears to listen to it, this provision is annulled for migrants. What is more, they are forcibly silenced as an expression of the exercise of power that hides the discomfort caused by that which you need "cleansing", under the pretense of a sonorous purity that desires, if read in more depth, a racial and linguistic purity that segregates those who "contaminate" the city with their presence and sonority.

This reflection points to the fact that silence is a communication that is not precisely discursive. David Le Breton stated that "silence is a feeling, a signifying form, not the counterpoint of the prevailing sonority" (2006: 10). From their symbolic power, these silences were the forms of hospitality offered in Tapachula, especially in the institutional sphere, to the Haitian community.

One of these is of a structural nature and affects migrants, as their needs and perspectives are often ignored and policies that affect them, most of them to their detriment, are applied. In this category there is also the silencing of the media and civil society; with respect to the former, it is rarely the protagonists who raise their voices in the mass media and they are almost always mediated by third parties. In this media discourse, it is common to find labels such as "a danger to the local economy", due to the decrease in sales, since, according to the perspective of the tenants, they "obstruct" the arrival of potential customers.

As an international consequence of restrictive migratory policies, there is the silence of those children of Haitians who were not born in that country and who, when they are deported to a place where they never lived, have serious difficulties of cultural reintegration. A related example is what has happened in the Dominican Republic through the ruling of the Constitutional Tribunal tc/In the same way, the law of the Republic of Haiti was amended to include a new law, the law of the Republic of Haiti, which, with the idea of "protection of the national identity", denied the right to nationality to Haitians born on the Hispanic side of the island, retroactively, which violently implied the diffusion of identity, thus violating one of the most fundamental human rights (Fresneda, 2023: 689).

There is also bureaucratic silence, closely linked to the previous one. It refers to the ineffectiveness of Mexican institutions, at least before which refuge is requested, thus positioning the applicants in a long pause and which can be read as a "containment mechanism" (Fresneda, 2023: 686) on the part of the Mexican government and in response to the pressures of the United States regarding the increase in the flow of Haitian people to the north. This point of the presentation is an opportunity to exemplify, through an institutional practice, this type of silencing.

As a result of the saturation of the appointment registration system of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a los Refugiados (eat), towards the end of 2021 a new and deliberate obstacle was introduced for those interested in obtaining a temporary visa, which, although it would not allow them to leave the state of Chiapas, in ideal terms would prevent them from police harassment and possible deportation. This new procedure consisted in that, in order to obtain an appointment in which it would be evaluated whether or not one was a candidate for refuge, one had to write, on a sheet of paper and in Spanish, the causes of the so-called "credible fear"; that is, to state the reasons that prevented one from returning to one's homeland. One of the causes of the saturation and subsequent ineffectiveness of the eat This measure, which did not consider the human right of the applicants to communicate in their native language, nor the rates of written literacy in a second language, has been one of the most perverse filters for the migratory regularization at the Mexican border of those who initially sought to reach the United States, but who have been stranded in a city that was not prepared to receive them and that, therefore, has skewed the spaces available to them.

Another example of this type of structural silencing occurred on November 17, 2021, apparently as a "recognition of migrant children", although in reality it was perceived by many as an ironic gesture of hostility. It was mentioned above that, as they arrived, the Haitian community found in the Miguel Hidalgo Park, in the center of the city and in front of the municipal government building, a place in which to settle, and that the needs of inhabiting that space transcended those of spending the night, because there they found a meeting point in which they coincided with others who, like them, were deprived of a "place of their own".

This appropriation of public space by non-citizens resulted in the cancellation of the communal use of the park: one day they were removed from the site and the next morning it was fenced off with yellow tape, the same tape used to protect crime scenes. Almost immediately, in that same square denied to migrants, the United Nations Children's Fund (Unicef) installed a sculpture by Javier Marín, titled Noise generated by the collision of the bodieswhose presence in this tense context and positioned specifically in that place was not particularly a sign of sensitivity and empathy.

This sculpture consists of the representation of bodies raised on a boat in the middle of the square. It is not in vain to mention that the bodies that Marín evokes seem to have no identity, they are totally covered, faceless and voiceless, silenced. The blanket that covers them seems to refer to the metal blankets with which migrants are covered in U.S. detention centers, and the raft on which they stand resembles the boats that people from Africa use to reach Europe, but also on this side of the continent, those of Cubans to reach the United States by sea. In addition to the fact that it looks like a sculpture out of place, in the situation in which it was placed, it can be read as another symbolic practice of silencing this population, unable to inhabit the square where, according to the interpretation of the municipal government that allowed its placement, homage was paid to them.

Although everything reported so far happened, as has been said, starting in 2021 when the population of this Caribbean island was much more present in Tapachula, these silencing practices have been constant and the possibilities of living in dignity have not improved. In 2022, it was recorded that at least seven migrants in street situations have died due to lack of medical attention for common illnesses, which, if left untreated, are complicated to the point of fatality. Wilner Metelus, president of the Citizen Committee in Defense of the Naturalized and Afro-Mexicans, attributes this precariousness to exclusion by local authorities and even regrets the indifference of organizations that, in the best of cases, should ensure better living conditions and recognize that this is a practice of social deafness, and condemns "the silence of the State Commission of Human Rights of Chiapas" (Henríquez, 2022).

The reaction with which many members of the Haitian community channeled the desperation and frustration of those who, although they do not know for sure, feel that they are being deceived was precisely this, making noise through silenceThe value judgments that qualified them as noisy and barbaric were put in check. After months of stoic patience, patience was finally exhausted, but the outburst, unlike what was expected, did not happen with thunder, but with silence as a weapon, accompanied by gestures of desperation.

This voice that moves between noise and language makes clear the unacceptable condition of exclusion that occurs at a corporal level. It suffers and makes known its suffering, demands an end to that suffering and a process of reparation. It refuses to accept that corporeality that engenders injustice: bodies that live in the limits of their sounds, bodies that struggle with unsolvable pain and political fervor (Butler, 2020: 79).

On August 23, 2021, a silent demonstration of several Haitian nationals gathered outside the facilities of the eat with signs in their hands in which they demanded what is fair: efficiency and promptness with respect to their requests for refuge to leave the city under the terms of the law. Minutes later, without the noise that usually accompanies collective demands, with serious and mute faces, they began to throw stones at the buildings of this institution, which, by the way, have tin roofs, making it impossible to hear their disagreement, although not shouted out loud: why talk if they were not heard. This was material evidence of the marginalization of this population in the city. Although this demonstration was promptly silenced by a police group, it was an indication of bodies that, from their possibilities, united with the objective of streamlining bureaucracies so that, finally, they could escape from a city where there was no space or opportunities for them.

The reading of this manifestation, which brought together feelings of frustration in the face of social disregard for the demands of a community historically marked by segregation, invites, in addition to the evident need to rethink hospital strategies that go beyond charity, to consider other forms of political expression outside the framework of the discourse as it has been interpreted up to now: if the presence of the other is inaudible, other ways of political demand are possible only through the presence in which a situation of exclusion is made evident from the body itself and which makes known, only with its beThe injustices that have been placed upon him, and at the same time he demands their reparation.

Towards final considerations

The occupation of public spaces can be in dispute between several communities and within these tensions power relations are generated; these are more evident when one of the parties has political disadvantages, such as the lack of immigration regularization documents, caused in turn by a disregard of the institutions that should provide this right. The cancellation of the use of Miguel Hidalgo Park, first with the installation of the fence for the placement of the statue that was supposedly intended to pay homage to the population in mobility and later with the felling and complete disabling due to deep renovations in the structure of the space, implied the transformation of a meeting point for the Haitian community into an inhospitable place and resulted in the displacement to a secondary space in terms of dimension and relevance, but from where the audible sound marks through music, the use of Creole as a device of intimacy and the presence of a strong representation of this population in the center of the city, give account of a kind of resistance, which insists on being heard while waiting, interacting at the same time with other communities in movement and with the resident population that slowly and daily becomes familiarity. However, in order to be heard in institutional contexts, the systematic deafness towards their demands, from which they emanate, provokes other strategies that bring into play the "noisy" appreciations of them, and as they have learned in other places and during the journey, they materialize other forms of discourse and demand through silence and the presence of the collective body.

Bibliography

Agier, Michel (2015). “Do direito à cidade ao fazer-cidade: o antropólogo, a margem e o centro”, Mana, vol.21, núm. 3, pp. 483-498.

Avella Alaminos, Isabel (2000). “Los cafetaleros alemanes en el Soconusco ante el gobierno de Carranza (1915)”, Anuario 2000 de la Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, pp. 445-476.

Bieletto, Natalia (2018). “De incultos y escandalosos: ruido y clasificación social en el México postrevolucionario”, Resonancias, vol. 22, núm. 43, pp. 161-178.

Butler, Judith (2020). Sin miedo. Formas de resistencia a la violencia de hoy. Nueva York: Penguin Random House.

— (2018). Corpos em aliança e a política das ruas. Río de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

Canales Cerón, Alejandro (2019). “La inmigración contemporánea en Chile. Entre la diferenciación étnico-nacional y la desigualdad de clases”, Papeles de Población, 25(100): 53-85. Disponible en <http://dx.doi.org/10.22185/24487147.2019.100.13>.

Cinta Cruz, Jaime Horacio (2020). Movilidades extracontinentales. Personas de origen africano y asiático en tránsito por la frontera sur de México. San Cristóbal: Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas/Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica.

Coulange Méroné, Schwarz (2018). “Elementos sociohistóricos para entender la migración haitiana a República Dominicana”, Papeles de población, 24(97), pp. 173-193. https://doi.org/10.22185/24487147.2018.97.29

Díaz Facio Lince,Victoria Eugenia, Astrid Natalia Molina Jaramillo, Manuel Antonio Marín Domínguez (julio-diciembre, 2014). “Significados, silencios y olvidos asociados a la experiencia del desplazamiento forzado”, Revista de Piscología Universidad de Antioquia 6(2).

Diccionario del Español de México (2023). Disponible en línea: https://dem.colmex.mx/Ver/esperar

Domínguez Ruiz, Ana Lidia (2011). “Digresión sobre el espacio sonoro. En torno a la naturaleza intrusiva del ruido”, Cuadernos de Vivienda y Urbanismo, vol. 4, núm. 7, pp. 26-37.

— (2014). “Vivir con ruido en la Ciudad de México. El proceso de adaptación a los entornos acústicamente hostiles”, Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, vol. 29, núm. 1(85), 2014, pp. 89-112.

Ferrer, Ada (2003). “Noticias de Haití en Cuba”, Revista de Indias lxiii (29): 675-694. Disponible en <https://doi.org/10.3989/revindias.2003.i229.454>

Fresneda, Edel José (2023). “Haitianos hacia el sur, desde la vulnerabilidad hacia la incertidumbre”, Revista Mexicana de Sociología, [S.l.], v. 85, n. 3, p. 669-696, junio. Disponible en http://revistamexicanadesociologia.unam.mx/index.php/rms/article/view/60776.

García, Jorge David (2022). “¿Qué podemos escuchar con tanto ruido?” Ponencia en el coloquio: Paisaje sonoro, música, ruidos y sonidos en las fronteras. Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, 24 de noviembre.

Hamilakis, Yannis (2015). “Arqueología y sensorialidad. Hacia una ontología de efectos y flujos”, Vestigios. Revista Latino-Americana de Arqueología Histórica, vol. 9, núm. 1, pp. 31-53.

Henríquez, Elio (2022, 12 de agosto). “En 2022 han muerto siete haitianos en situación de calle en Tapachula”, La Jornada. https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2022/08/12/estados/en-2022-han-muerto-siete-haitianos-en-situacion-de-calle-en-tapachula/

Le Breton, David (2006). El silencio. Madrid: Sequitur.

Louidor, Wooldy Edson (2020). “Trazos y trazas de la migración haitiana post-terremoto”, Política, Globalidad y Ciudadanía 6 (11). Disponible en <https://doi.org/10.29105/pgc6.11-3>.

Peña Battle, Manuel A. “El sentido de la política”. Discurso pronunciado en Villa Elías Piña el 16 de diciembre de 1942, en la manifestación que allí tuvo efecto en testimonio de adhesión y gratitud al generalísimo Trujillo, con motivo del plan oficial de dominicación de la frontera. http://www.cielonaranja.com/penabatlle-sentido.htm

Polti, Victoria (noviembre, 2011). “Aproximaciones teórico-metodológicas al estudio del espacio sonoro”, en La antropología interpretada: nuevas configuraciones político-culturales en América Latina. Buenos Aires: conferencia disponible en Actas del x Congreso Argentino de Antropología Social.

Sabido Ramos, Olga (coord.) (2019). Los sentidos del cuerpo: el giro sensorial en la investigación social y los estudios de género. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de Género.

Savasta Alsina, Mene (2020). “¿Cómo se escucha el arte? Arte sonoro y auralidad contemporánea”, Sulponticello, revista online de música y arte sonoro. iii Época. Disponible en https://sulponticello.com/iii-epoca/como-se-escucha-el-arte-arte-sonoro-y-auralidad-contemporanea/

Suárez-Cabrera, Dery Lorena (2015). “Nuevos migrantes, viejos racismos: los mapas parlantes y la niñez migrante en Chile”, Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 13(2): pp. 627-643.

Mónica Bayuelo García (Querétaro, Mexico,1990). Master in Social Anthropology by the ciesas Unidad Noreste and a bachelor's degree in Hispanic Language and Literature from the unam (fes Acatlán). Her lines of research focus on the socioanthropology of the meanings of migration. She has been awarded with honorable mention in the Fray Bernardino de Sahagún Award in the category of Master's Thesis (2022) for her work "Migración de riesgo en el tránsito noreste. Subjectivities from a meaningful listening".