The house of dreams, heritage and mausoleums

- Patricia arias

- ― see biodata

The house of dreams, heritage and mausoleums

Receipt: August 31, 2023

Acceptance: January 15, 2024

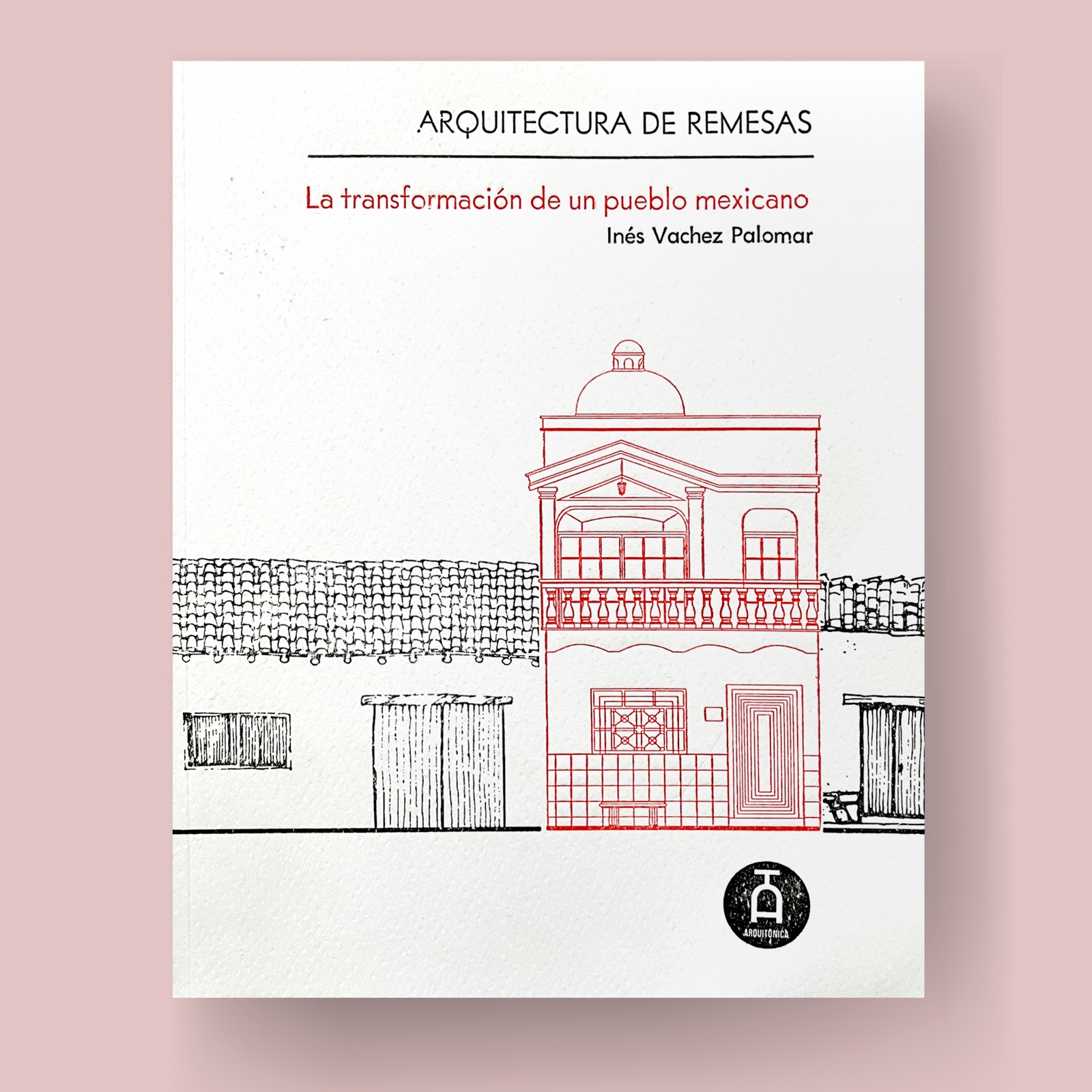

Remittance architecture. The transformation of a Mexican town

Inés Vachez Palomar, 2023 Arquitónica-Analog Typologies, Guadalajara, 110 pp.

Remittance architecture. The transformation of a Mexican town is the result of recent research and reflection by Inés Vachez Palomar on a topic that has been mentioned in several studies over time: the importance of the home in the destination of rural migrants' remittances. In the eighties, Douglas Massey et al. (1991) found, for the first time in the study of Mexican migration to the United States, that the initial destination of remittances was precisely the construction of their own homes in their communities of origin. In the following years, several ethnographies of rural communities in various regions of Mexico documented that the construction of a house had become a priority objective of migrants to the United States.

The ethnographic findings alluded above all to the rearrangements in domestic arrangements that began to arise from the house-remittances that reached households in greater amounts and with greater regularity than those that, in previous times, had been destined to traditional financing of agrarian societies: agriculture, purchase of land, animals, offices and patron saint festivities, weddings (Arias, 2009). The construction of houses also began to be documented as a main source of investment of remittances from Bolivians, Peruvians and Ecuadorians who had migrated to Europe, especially to Spain. In general, the changes in the domestic and family relations of the remittance-house attracted more attention than the houses themselves.

The novelty of Inés' research consists in having chosen migration to the United States as the central and explicit axes of her work, but from the angle of its link with the transformation of rural architecture; in other words, the study of the houses built by the "northerners", a field of research that until now has been practically unexplored, beyond descriptive allusions. Inés has done so from her particular vantage point as an urban researcher and a personal circumstance: that of someone who spent her childhood summers in the Santa Cruz del Cortijo hacienda, an agrarian property from which the town of Vista Hermosa emerged and to which she returned, in 2022, to conduct the research that has culminated in this book.

The text is interwoven with historical data and social theories, but mostly from observation, conversations and interviews. Most of the information comes from nine people whose individual and family trajectories have been shaped by migration to the United States. The text dialogues with numerous photographs, old and present, sketches, plans and drawings.

Vachez gives an account of the factors that accumulated to make migration to the United States become the main alternative to achieve the "dream of home ownership" for the residents of Vista Hermosa. As he documents, this small town in the municipality of Tamazula, located in southern Jalisco, resisted the onslaught of the Mexican Revolution, the Cristero War and the distribution of land, which in that region followed a particular path: the landowners distributed the property among their workers as a way to maintain the activity of the sugar mill, which continued to be theirs. But also, since 1940, according to the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (inegi, 2023), Vista Hermosa is categorized as an ejido, i.e., there was an agrarian distribution there.

It should be remembered that one of the main achievements of the 1910 Revolution was precisely the provision of arable land so that rural people could make a living from farming on their plots of land. Mexico was a predominantly rural and agricultural society and the post-revolutionary State designed various mechanisms to guarantee the population's access, basically men, to land and crops.

In the 1960s, in Vista Hermosa, as in so many rural communities in Mexico, the first signs appeared that the distribution of land, as well as the old agro-industrial activities, such as the traditional sugar mills, had ceased to guarantee the survival of the new generations of peasants. In this town, everything worsened since the sale of the sugar company to the Tamazula sugar mill, which left the community's neighbors without a market for sugar cane and without work. And there, as happened in so many towns in Mexico, especially in Jalisco, labor migration, predominantly male, to the United States was unleashed.

One area that remained outside the scenarios of post-revolutionary government intervention was housing. This had previously been taken care of by the hacienda, which provided small houses for its workers and, on the ranches, for the medieros who took care of the cattle. Until a few years ago, excellent examples of this vernacular architecture were preserved in the Sierra del Tigre, near Inés' study area. In indigenous societies, the Mesoamerican system of reproduction, based on patrilineal principles, guaranteed young men access to family plots where they could build houses.

In general, it can be said that the most deeply rooted building traditions in Mexico are self-construction, construction in stages and family collaboration. Migrants in the United States, but also internal migrants, that is, those who went to live in different cities in Mexico, have been the greatest creators of particular architectural typologies in the spaces to which they had to move and which they filled with activities, aesthetics, dreams and meanings that we can still find today; an example of this was the Libertad sector in Guadalajara or in the immense urban world that emerged behind the Mercado La Merced in Mexico City.

Inés' research in Vista Hermosa has allowed her to propose four typologies of life that show how migration has effectively contributed to solve the residential needs of the neighbors. The most fortunate combination, that is, the one that allows to build and return to live in the house of dreams, is that of the legal international migrant who, thanks to this condition, is able to obtain higher income, can build his house in less time and return in better economic conditions.

The construction of the houses, Inés points out, is an objective in process as it depends on multiple vicissitudes that modify it throughout the migratory journey: the variable income that can be destined to the house; the changes in the composition of the domestic groups; the incorporation of successive elements collected from experiences, trips, fashions, tastes, imitations that the migrants or also the masons add, with great freedom, to the constructions. The houses already built are the proof, but also the incentive to reiterate that migration is the main, perhaps the only way to achieve this objective, despite the sacrifices it imposes on the domestic groups, the families and the community.

The interviews conducted by the author show an irrefutable fact that constitutes a 360-degree change in the migratory experience and the relationship with the houses. Until the 1990s, after the construction of the house, migrants invested their remittances in resources that would guarantee them a labor insertion and a source of income: land, land, ranches, animals, machinery, premises, which transformed their social position in the communities and modified the destiny of their descendants (Massey et al., 1991). Migrants' productive investments diversified and expanded the supply of activities, jobs and income for people in the communities.

However, all that changed in the 1990s with the Immigration Reform and Control Act (ircaThe legalization of undocumented migration and the persistence of undocumented migration in the United States. Since then, legal migrants began to stay and live and work on the other side and undocumented migrants had more and more problems to go and return, regularly and safely, as it had been during the previous decades. This change forever altered the meaning of the houses built with remittances.

Currently, as Inés shows, the remittance houses belong to husbands and sons who are in the United States, who have not returned for years, if not decades, and the constructions have been in progress for more than ten or even 30 years. The working world of the neighbors is outside and far from the community. They will be inhabited, in the best of cases, when their owners' working lives are over and they can return to Vista Hermosa as retirees.

Vista Hermosa is not unique in this regard. The resources and activities of many rural communities like Vista Hermosa make it very difficult, if not impossible, for rural households to survive. According to the inegi (2023), the town has never had more than four thousand inhabitants -since 1970 it has fluctuated between 3,500 and 3,900 residents- and its growth rate has been negative or very low. This situation has changed the meaning of the enormous effort of migrant labor: the houses will be retirement homes or, as interviewees told Vachez, they will be part of a heritage for their descendants. The semantic change is not minor. The objective of the dream house has become a more diffuse purpose: heritage. To this must be added the violence, increasingly present in rural communities such as the one analyzed in this book, which has become an additional reason for the departure and emptying of rural communities.

For Inés, migrant houses correspond to a "free" architecture in terms of "morphology, color, construction elements, size", in which common elements and unique combinations can be seen. This "free" architecture has given rise to patterns with ingredients of different origins and symbols of diverse traditions, but which are repeated in the houses of migrants of all times, in all places: the house, large, eclectic, profusely decorated, especially on the exterior, with novel elements that break with the typologies, the language and the meanings of the vernacular architecture of the communities.

In the interiors of the houses, Inés has noted the persistence of components and products that recall the functionality and attachment to the objects of yesteryear: the street benches, the altars to the Virgin of Guadalupe, but especially in the kitchen: the sink, the comal, the molcajete, the metate. The author does not mention elements that have been pointed out in a still anecdotal way, such as the lack of space for laundry and clotheslines, which do not exist in homes in the United States, the need for which is felt when migrants return home. But, as he notes, this is happening and will happen less and less.

As Inés rightly points out, this is an architecture of great endogenous value that has taken years of effort and corresponds to the tastes, dreams, aspirations, representations and new identities of migrants and of enormous importance for the public image they want to project. In fact, a central intention of the research has been to recognize in migrants' houses "their immense value, which goes far beyond the aesthetic canons determined by a Eurocentric heritage and imposed by a privileged minority" (Vachez, 2023: 10) for tourist consumption.

However, migrant architecture is very different from what today is valued in aesthetics, real or created, that privilege the colonial or pre-Hispanic elements of rural communities, as happens, for example, with the Magical Towns. In this context of emptying of economic activities and of not being part of the architectural and recreational trends that attract tourists, what will happen to the migrant architecture of localities such as Vista Hermosa?

There are some clues. Vista Hermosa is part of what can be considered a lineage of localities that, at different times and contexts, have created an architecture based on remittances laboriously obtained abroad and invested in the places of destination. This happened, for example, with the Indianos, those Spaniards who after years of work in some Latin American country, returned and showed the result of their efforts with the construction of huge houses that, with the large palm trees that identify them, modified the built space and architecture of countless communities in Catalonia, the Basque country, Asturias, Cantabria. For the time being, it is mainly books of photographs that have documented them (Braña, 2010). With their excesses and false coats of arms, they were houses designed for the return of the Indianos as retirees, that is, who would not have to work, but, in the best of cases, worry about their business. But, apparently, they could not be maintained as family homes. Thanks to the tourist conversion of many of these rural towns in Spain, these mansions have been converted into hotels, paradors and restaurants.

Another example is the houses of the barcelonnettes, those French migrants so close to the modernization of commerce and the textile industry in Mexico and, of course, in Guadalajara (Gouy, 1980). The barcelonnettes -called there "the Mexicans"- built huge houses for their return and retirement in that small community in the French Alps. They are known as Mexican mansions or castle-mansions (Homps, 2023; Wallace, 2017).

In Barcelonnette are preserved, it is said, 51 magnificent residences, unique in the region, which serve as summer homes for a locality that today, like so many, lives on tourism (Wallace, 2017). But, as Hélèn Homps (2023) notes, the interwar crisis on both sides of the ocean gave way to new trends: the construction of retirement homes and the construction of huge, modern and novel tombs, which announced, perhaps unwittingly, that the return of migrants would be only to rest forever in the longed-for land.

A recent article by Martha Muñoz and Imelda Sánchez (2017) has brought to light a peculiar phenomenon in Jalisco. For many years now, the neighbors of Santiaguito de Velázquez, like those of Vista Hermosa, became migrants, in their case internal migrants, who scattered throughout the national geography to establish taquerias that have brought them fame and fortune. The innumerable Arandas Taquerias are, in their immense majority, owned by neighbors of this tiny town in Los Altos de Jalisco. And, like those of Vista Hermosa, they built huge mansions for their return. However, after three or four generations as migrants they have learned that they will not return to Santiaguito because business forces them to stay in their destination places. But everyone wants to have a place in the town cemetery, which has triggered an impressive migrant funerary architecture that is part, as Martha and Imelda point out, of the evidence of success (Muñoz and Sánchez, 2017).

The concern of the Santiaguito migrants is now the construction of impressive tombs and mausoleums that cost more than a house of social interest and are maintained, in perfect condition, by gardeners and caretakers. So much so that the delegate's concern, he told Martha and Imelda, was to obtain land to enlarge, not the town, but the cemetery to which they would all return at the end of their working lives, to rest, now in peace and among their own.

It is impossible to know what will happen in Vista Hermosa, but something similar is glimpsed in this book by Inés, in the imposing photograph of the mausoleum of a Vista Hermosa migrant family that mimics the entrance to the White House in Washington, d.c.

Readers of this book will find that and much more, without a doubt, an original, novel, necessary, well written, carefully illustrated and edited work, to understand through the houses, which is Inés' proposal, the formidable changes and dilemmas of the migrants and the people of the Jalisco countryside today.

Bibliography

Arias, Patricia (2009). Del arraigo a la diáspora. Dilemas de la familia rural. México: Miguel Ángel Porrúa/Universidad de Guadalajara.

Braña, Alejandro (2010). Asturias, tierra de indianos. Vega: Ediciones Nueve Doce.

Gouy, Patrice. 1980. Pérégrinations des “Barcelonnettes” au Mexique. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

Homps, Hélèn (2023). “El testamento arquitectónico de los barcelonnettes –el gran almacén, la mansión y la capilla funeraria– o el triunfo del eclecticismo”, en Javier Pérez Siller y David Skerrit (eds.). México-Francia. Memoria de una sensibilidad común. México: Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos, pp. 217-228.

Massey, Douglas, Rafael Alarcón, Jorge Durand y Humberto González (1991). Los ausentes. El proceso social de la migración internacional en el occidente de México. México: Conaculta/Alianza.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2023). Archivo Histórico de Localidades Geoestadísticas https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/geo2/ahl/ Actualización de la información 30 de junio de 2023.

Muñoz Durán, Martha e Imelda Sánchez García (2017). “La evidencia del éxito. Residencias y mausoleos en Santiaguito, Arandas, Jalisco”, en Patricia Arias (coord.). Migrantes exitosos. La franquicia social como modelo de negocios. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, pp. 99-147.

Vachez, Inés (2023). Arquitectura de remesas. La transformación de un pueblo mexicano. Guadalajara: Arquitónica-Analog Typologies.

Wallace, Arturo (2017). “La fascinante historia de cómo Barcelonnette se convirtió en la ‘capital de México’ en Francia”. bbc News Mundo. Recuperado de https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-40979695 Consultado el 31 de mayo de 2024.

Patricia arias D. (New Regime) in Geography and Territorial Planning from the University of Toulouse-Le Mirail, France. Emeritus Researcher at the sni. Recent publications: (2021) From agriculture to specialization. Debates and case studies in Mexico (with Katia Lozano, coords.). Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara. (2020) "De las migraciones a las movilidades. Los Altos de Jalisco", in Social IntersticesYear 10, No. 19, March-August. (2021) "Una revisión necesaria: la relación campo-ciudad", in Hugo José Suárez, "Una revisión necesaria: la relación campo-ciudad". et al. Towards an agenda for rethinking the urban religious experience: issues and instruments.. Mexico: unam(2021) "La migración interna: Despoblamiento y metropolización", in Jorge Durand and Jorge A. Schiavon (eds.). Jalisco: land of migrants. Diagnosis and public policy proposals. Guadalajara: Jorge Durand Chair of Migration Studies, cide/Konrad Adenauer Foundation/Government of the State of Jalisco.