From the Darien Gap to the Tapachula Gap. Mapping and shaping of new routes for migrants moving to the United States.

- America A. Navarro López

- Alberto Hernandez Hernandez

- ― see biodata

From the Darien Gap to the Tapachula Gap. Mapping and shaping of new routes for migrants moving to the United States.

Receipt: April 26, 2024

Acceptance date: October 31, 2024

Abstract

A geographic and sociological investigation was conducted on the routes used by migrants who cross the Darien and enter Mexico through Tapachula in order to reach the United States. Methodologically, we combined cartographic analysis, interviews and field visits. In addition, points were taken gps (Global Positioning System) to spatialize the presence of the National Guard (gn) in the Chiapas Costa-Soconusco corridor. The research is relevant because it reveals new routes and the migrants' skills to achieve their purpose, in addition to the fact that among those interviewed, the perception of Tapachula as a prison city facing challenges similar to those of the Darien emerges. Finally, it is important to point out that, based on their narratives, the first geo-referenced database of the routes in Tapachula was constructed. sig (Geographic Information System).

Keywords: migratory corridors, forced displacements, Latin American borders, GIS

from the darien gap to tapachula: mapping a new route of the displaced to the united states

This article provides a geographic and sociological analysis of the routes used by immigrants who cross the Darien Gap and enter Mexico at Tapachula on their way to the United States. The methodology combines mapping with interviews and field visits. Using GPS coordinates, the positions of the Mexican National Guard were mapped on the Chiapas coastal highway through Soconusco. The research reveals new routes and the skills migrants develop as they make the journey. It also delves into the perception among those interviewed of Tapachula as a prison-city with risks similar to those immigrants face in the Darien Gap. Finally, immigrant narratives of the journey were used to build the first georeferenced database of migrant routes using Mexico's Geographic Information System (sig).

Keywords: forced displaced, migrant routes, Latin American borders, sig.

Introduction

Colombia and Panama share a 266-kilometer border that connects the Pacific Ocean with the Caribbean Sea. The nodal point of this territory is a natural barrier - the Darien jungle - that divides Central and South America and interrupts the route of the Pan-American Highway; the Darien is covered with jungle vegetation, rivers, swampy areas, mountain ranges, wildlife, conservation areas and indigenous population reserves. In short, its challenging physical-geographical characteristics make penetration and mobility in the area difficult (Pan-American Highway Congress, 1991; Botero, 2009; Ficek, 2016; Corbino, 2021).

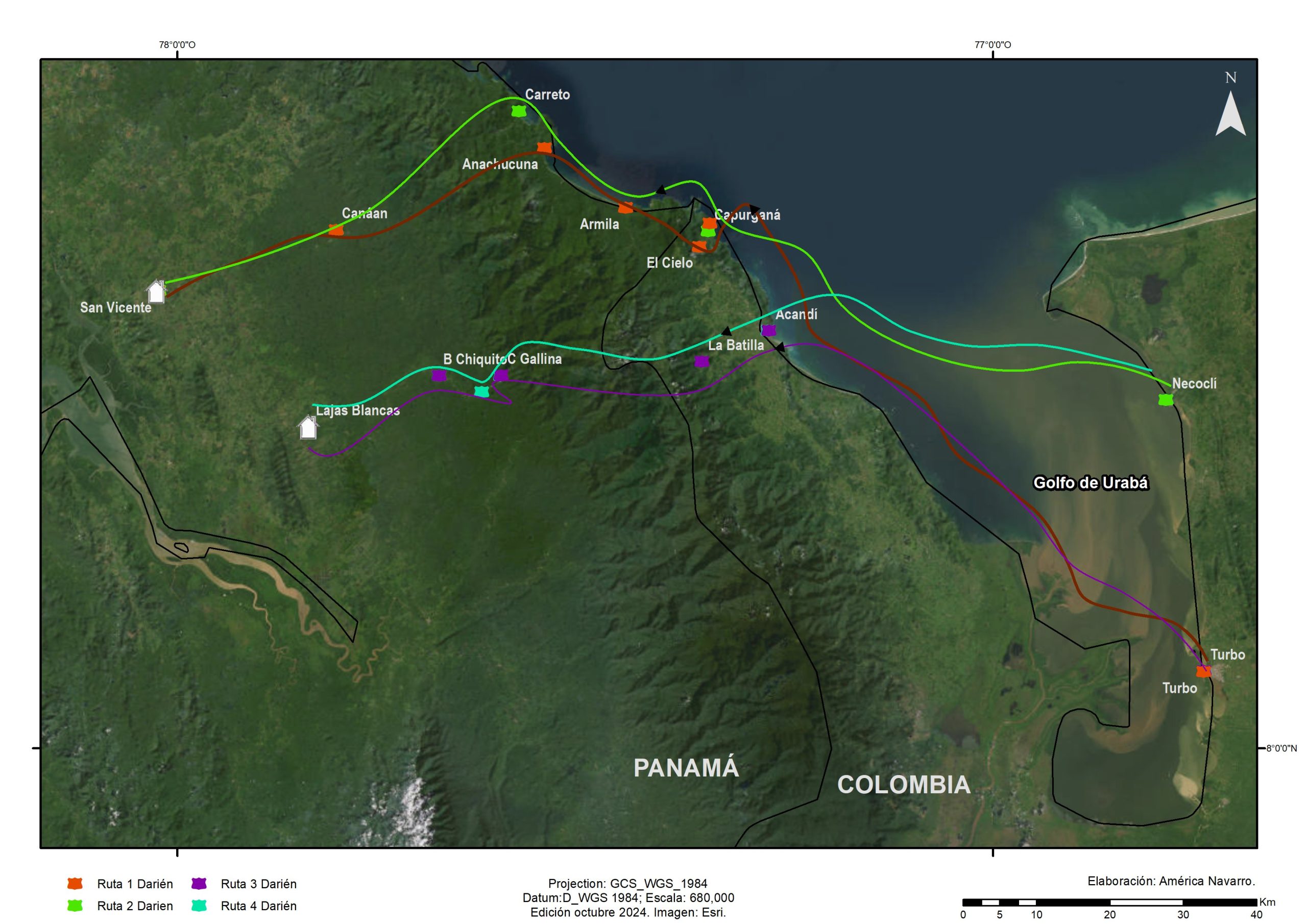

The Darién, a territory on the margins, is an example of how the boundaries between legitimate and illegitimate armed actors blur, forming a complex tapestry of violence and power. Historically, crossing this jungle has represented a great challenge for explorers, settlers, displaced populations and migrants, as it entails multiple risks and dangers. Over time, settlements, docks and trails near the border have become hubs for the trafficking of arms, drugs and, in recent years, humans. For decades, guerrilla and paramilitary groups have controlled this area, regulating access according to the implications for their illicit operations (Polo et al., 2019) (see Map 1).

In general terms, studies on the Darien have addressed different topics. Research from environmental history (Castro, 2005; Alimonda, 2014), frontier studies (Carreño, 2012; Luque et al., 2019; Corbino, 2021), irregular transit, human smuggling and humanitarian aid (León and Antolínez, 2021; Polo et al., 2019; Cabrera and Carrillo, 2022; Schmidtke, 2022; Echeverri et al., 2023; Porras, 2023; Severiche et al., n.d.), migration corridors (Zamora et al2008; Álvarez et al., 2021; Miranda, 2021; Bermudez, 2021; Bermudez, 2021. et al., 2023) and new methodological challenges (Hernández and Ibarra, 2023). However, this space has not been studied from an interdisciplinary perspective that combines geographical and sociological analysis to identify new migration corridors between the Darien Gap and Tapachula; this is our intention.

The article is divided into three parts that offer new cartographies on the tracing of traditional and new migratory routes.1 In the first one, the crossing of the Colombia-Panama border is addressed, emphasizing the adversities faced by migrants in the area known as the Darien Gap. The second part focuses on the transit through Central American countries. Finally, the third part deals with the crossing through Mexico, with a brief historical reference to the transfer of people in La Bestia, in order to allude to the traditional routes that operated for a long time. In this section we focus on the southern migratory corridor of Chiapas, characterized by a strong militarization. Tapachula is presented as a new bottleneck, as stated by the migrants interviewed, who assumed they were in transit and were stuck, as they put it, "imprisoned", in periods of varying length, partly due to the measures imposed by the United States on Mexico, which acts as an extended southern border of the neighboring country.

Methodological processing

The research was based on mixed methodologies that integrated the cartographic analysis of routes, based on information from interviews, field visits, participant and non-participant observation, as well as statistical data from the National Border Service (Senafront) of the Panamanian government and the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (comar), which were subsequently geo-referenced, making it possible to build the first spatial databases on the subject. Likewise, considering the importance of comparing data with the spatial reality of the problems addressed, the following points were taken into account gps to spatialize the control exercised by the National Guard (gn) in the southern migratory corridor of Chiapas. The processing of these data using the software ArcGis Pro allowed to obtain inputs for the cartographic elaboration.

The interviews, the main source of qualitative data, were individual and sometimes group interviews, in some cases semi-structured and in others unstructured, based on guides designed for the field trips. In the Darien jungle, several interviews were not recorded due to fear of the informants and security reasons. The recorded interviews, lasting from 20 minutes to an hour depending on the mobility conditions of the participants, were always conducted with their approval.

Between 2018 and 2024, more than 60 migrants were interviewed, mainly from Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Cuba and Haiti, in transit through border points in Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala and Mexico. In addition, five cases of people who managed to reach the United States were followed up through video calls and telephone calls; they were in various cities such as Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, Mexico City, Saltillo, Monterrey, Denver, Seaforth, New Jersey and New York. In all cases our interest focused on the narrative of the routes and the experiences that the interviewees had with the actors involved in these long international journeys. The objective was to test whether changes in the routes and the actors had occurred.

The border points visited were Capurganá, Sapzurro, Acandí (Colombia), Paso Canoas (Panama-Costa Rica), Los Chiles (Costa Rica), San Pancho (Nicaragua), as well as Ciudad Hidalgo, Talismán and Tapachula (Chiapas). In these places, unstructured interviews were conducted with migrants, public officials, migration personnel, customs, police, migrant smugglers, guides, street vendors, cab drivers, motorcycle cab drivers and other key actors.

This methodological design makes it possible to consider the new cartography generated as an analytical tool, since by projecting it onto a map, it can be used as a tool for the analysis of sig spatial patterns of position, coincidence, distance and journeys undertaken by migrants can be observed from the sources. It also offers readers the opportunity to approach the experiences of those who move through Latin American territories, thus promoting a more comprehensive understanding that links the social and spatial dimensions.

The Darien Gap: navigating through the jungle

Entering the Darién from Colombian territory is an arduous journey. According to field research and on-site interviews, the usual route is from the port of Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca, to Bahía Solano, Chocó, with an estimated duration of 22 hours by boat plus six hours by speedboat. The next itinerary is Bahía Solano-Juradó, which takes approximately three hours by speedboat, plus one hour to reach the port of Jaqué, Panama; the trip continues by ferry for 16 and a half hours to Puerto Quimba, the connection point with the Pan-American Highway. This is an old route that was used mainly for drug trafficking and today, due to the high cost of transportation and extreme maritime surveillance, it is rarely used. et al. n.d., n.d.) (see Map 2).

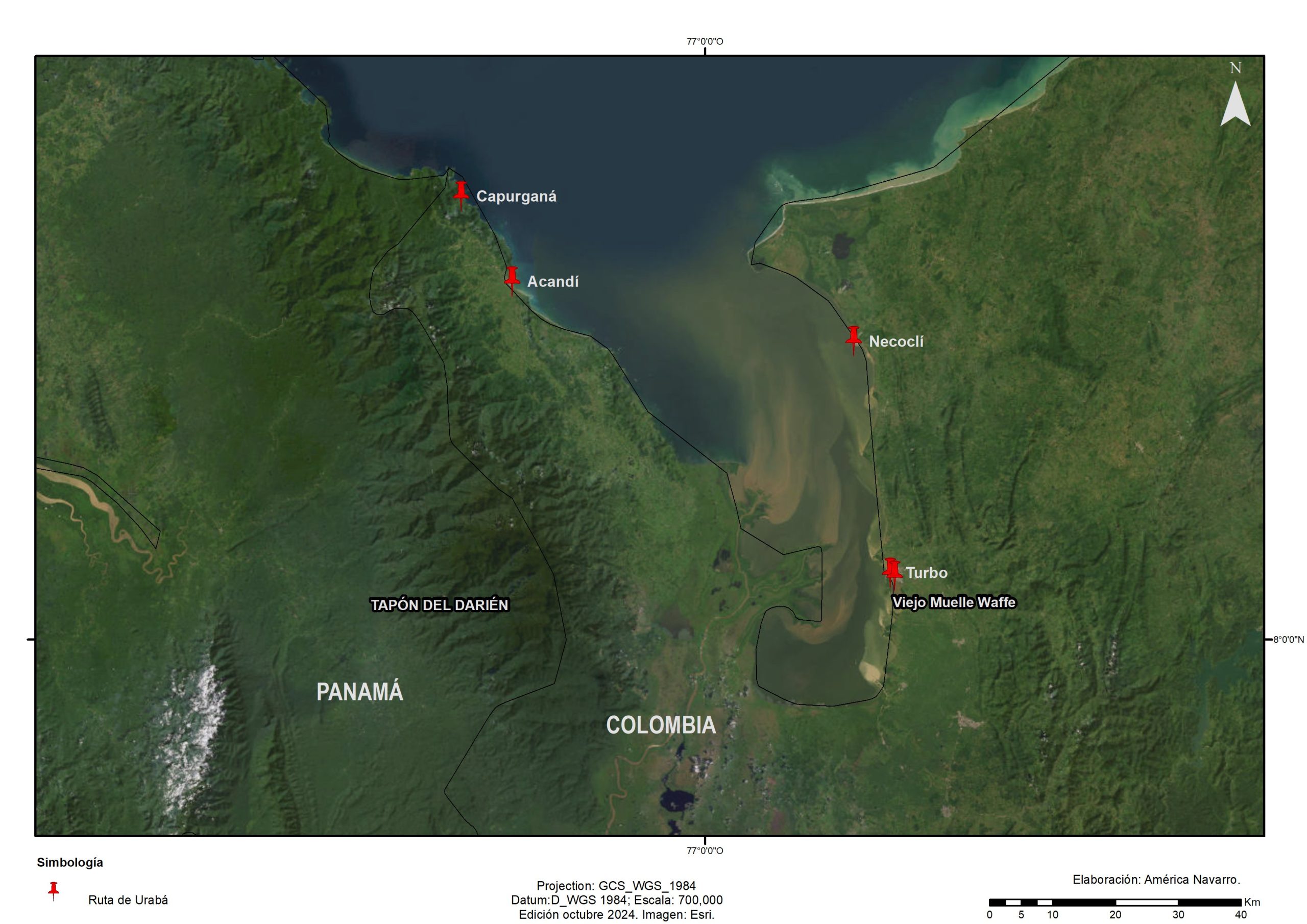

Other points of entry to the Darién have been the jungle towns near the Atrato River, although these routes were closed in the previous decade by paramilitary groups and the National Liberation Army guerrilla (eln). Therefore, to connect Colombia with Panama it is necessary to cross the Gulf of Urabá, a tongue of sea with an area of approximately 1,800 km² that includes the delta of the Atrato River. On the coasts of this gulf are Turbo and Necoclí, in Antioquia, which have consolidated as points of fluvial connection to Acandí and Capurganá, in Chocó (Botero, 2009).

Initially, this trip was made in the so-called pangas.2 In Turbo, the old El Waffe dock became the departure point for these vessels, and some time later the shipping companies modernized and introduced catamaran-type vessels.3 Since 2010, these four localities emerged as the main transit and connection zones for migrants in the Darién rainforest (Hernández and Ibarra, 2023) (see Map 3).

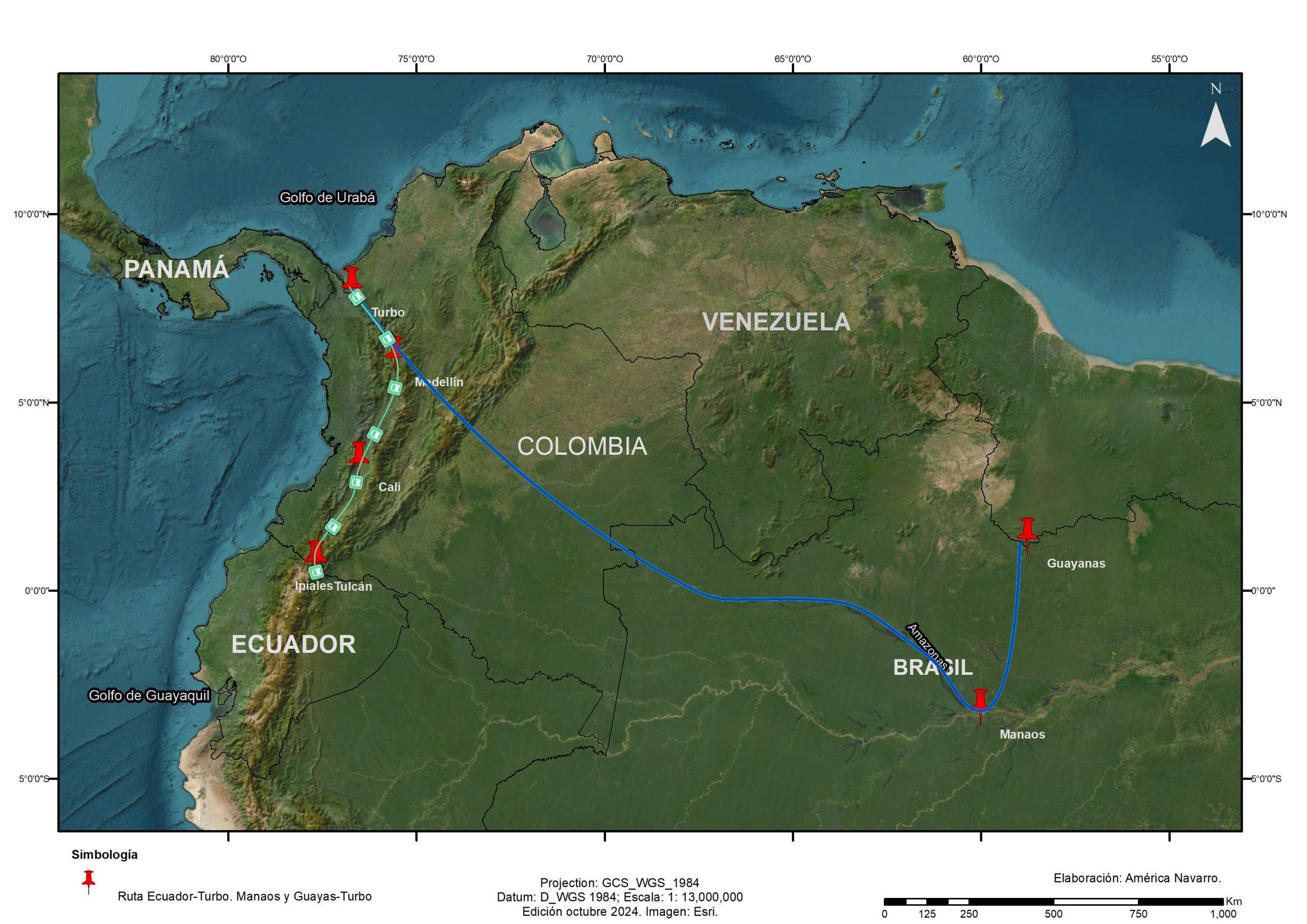

With the opening of Ecuador as a free transit country, a 1,200 km land corridor by bus was created from the Tulcán-Ipiales border to Turbo, with several transportation lines offering direct service or through connections in Cali and Medellín (Ceja and Ramírez, 2022). For their part, migrants departing from the Guianas or Manaus, Brazil, arrived in Turbo after crossing the Amazon region for several days by boat. Turbo became the most used transit route for those intending to cross the Darién (see Map 4).

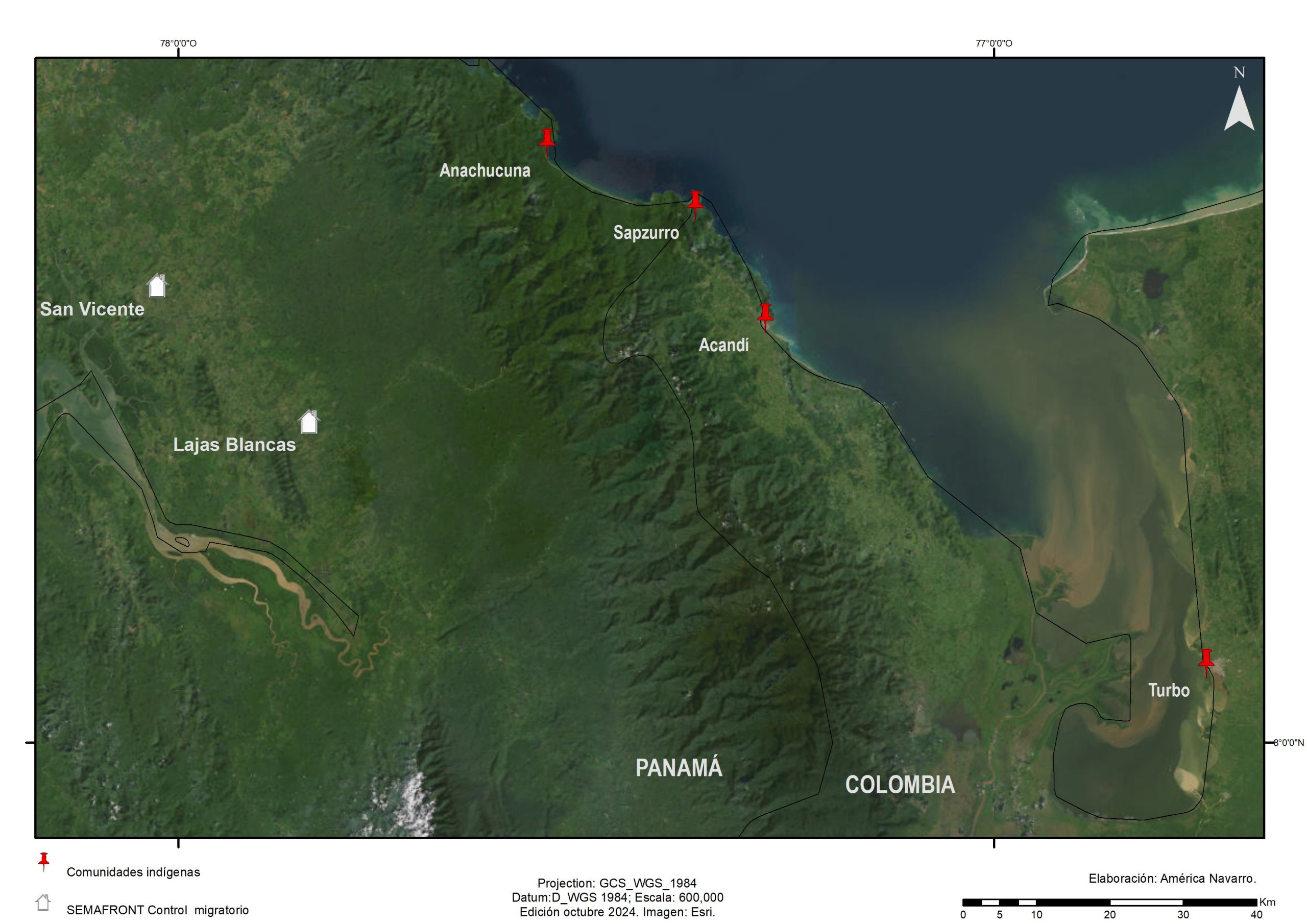

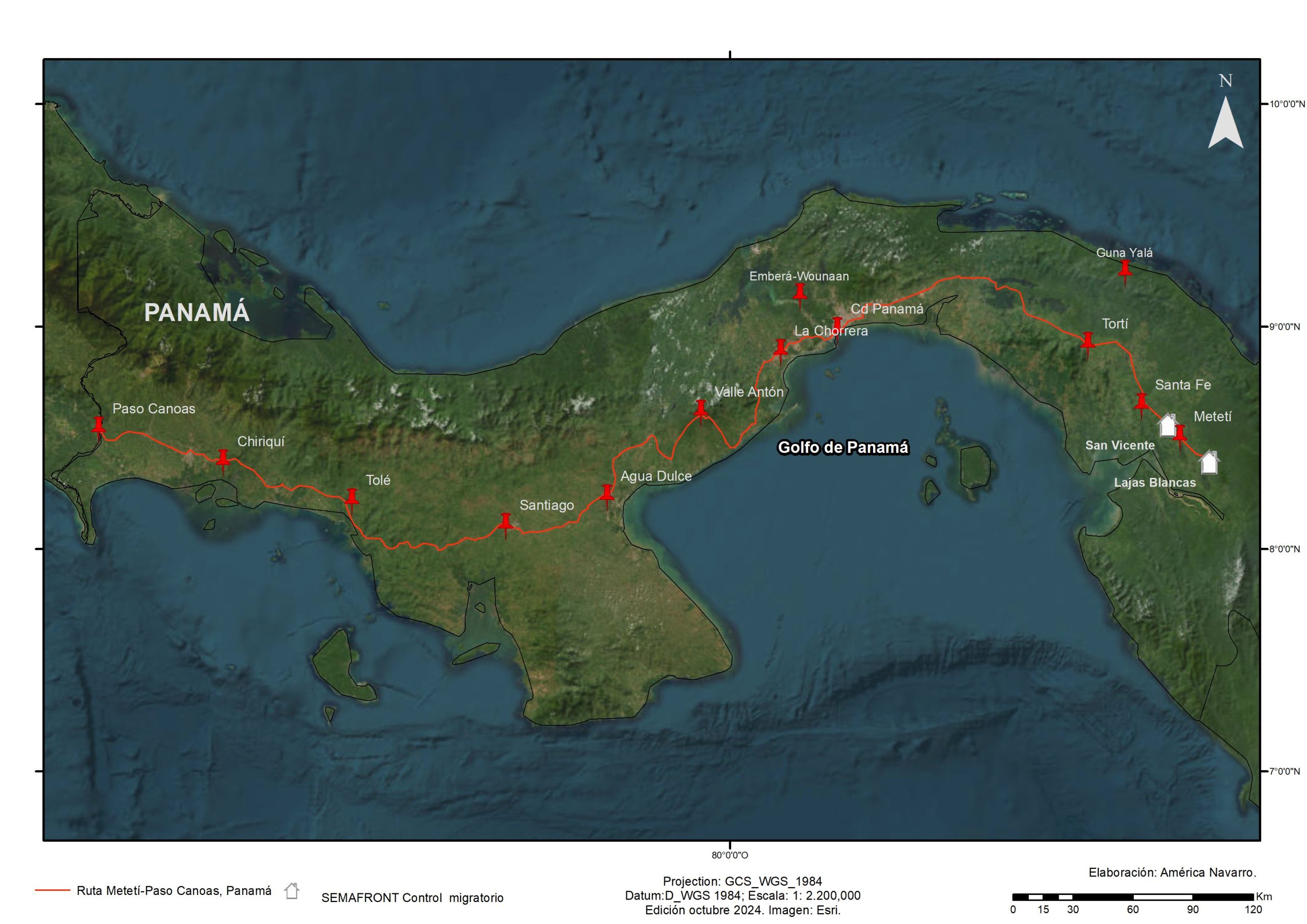

Given this scenario, in 2014 the Panamanian government decided to establish two migration control stations: one in Lajas Blancas and the other in La Peñita (now San Vicente), operated by Senafront. Thanks to the activity carried out at these stations, it is possible to know the number of migrants who crossed the Darien, as well as their nationality, sex and age (see Map 5).

According to these data, in 2014 there was a record of 6,175 migrants. In 2015 the flow increased to 29,289, of which 85% were of Cuban origin; the Turbo-Acandí-Sapzurro route was established as the usual way to enter this jungle (Senafront, n.d.). Perhaps without realizing it, this crossing would become the true feat of the Cuban flow, from which only a few would manage to get out alive (see Map 5).

In those years, for most of the immigrants, the journey took between four and seven days, crossing trails, rivers and highlands, and enduring extreme humidity, food shortages and continuous rain. Only those with more economic resources could border the coastline by boat, shortening their journey to reach the indigenous town of Anachucuna, another key entry point to the jungle (see Map 5).

Thus, in a relatively short period of time, flows through the Darién diversified and the volume of migrants increased. Those of Cuban and Haitian nationality explored other paths, creating new routes and challenging risks, which represented a logistical challenge that exposed the misery of the human condition (Clot and Martinez, 2018) and caused them numerous heartaches and losses that became their saddest stories.

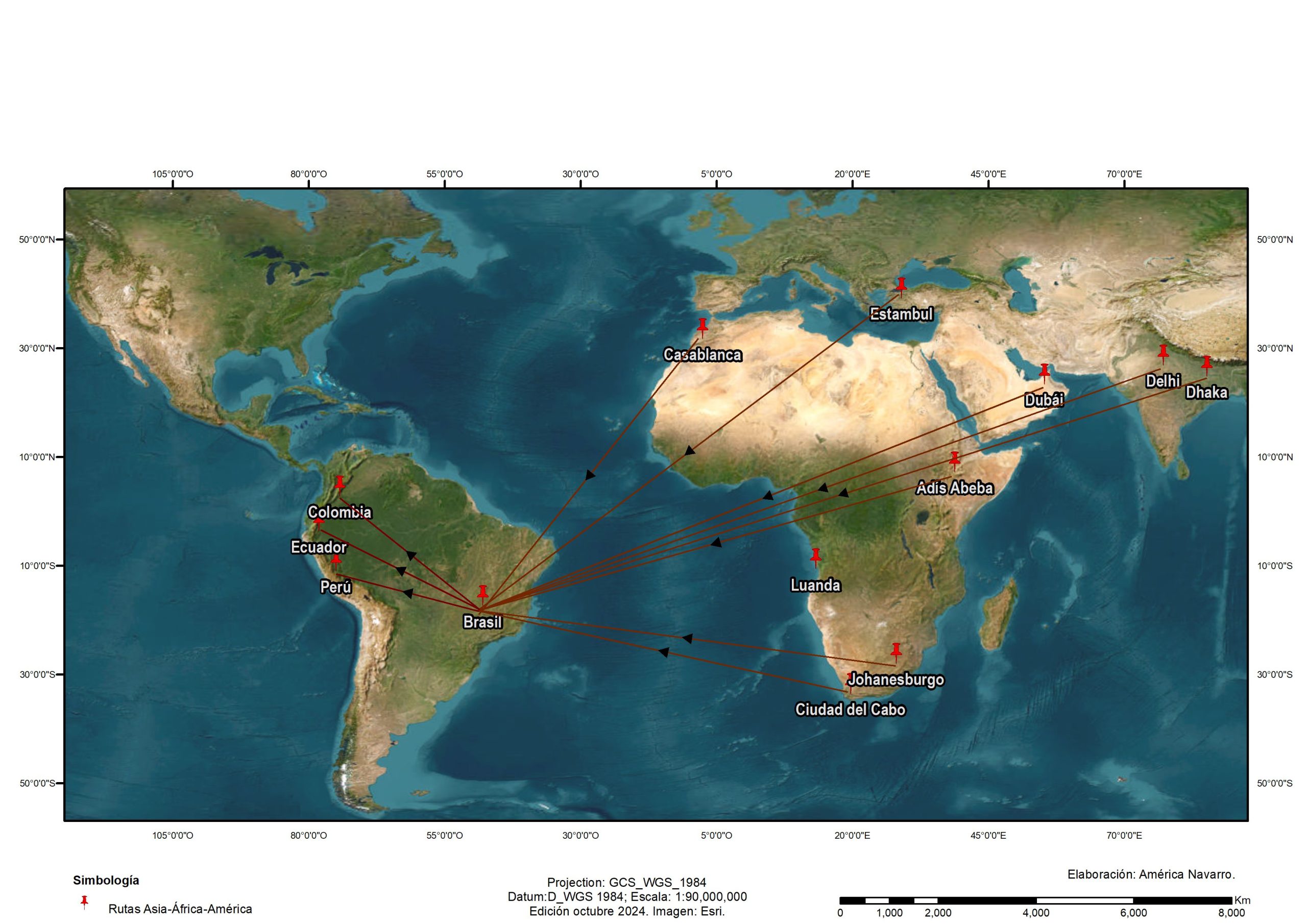

Europe, the first frontier

At the same time, the hardening of European migratory policy resulted in measures of all kinds to limit the arrival and free transit of migrants of African and Asian origin, which prompted this population to look to America, especially the United States, as a new destination and place of possibilities. Delhi, Dhaka, Istanbul, Dubai, Johannesburg, Cape Town, Casablanca, Luanda and Addis Ababa became air connections from the Indian subcontinent and Africa to Brazil. From there, this flow would move by various means to Peru, Ecuador and Colombia (Vilchez, 2016) (see Map 6).

Thus, crossing the Darien became an opportunity for people in mobility from the other side of the Atlantic. According to data from Senafront (n/d), during 2018 almost half of the migrants who entered irregularly through the Lajas Blancas and San Vicente stations came from India and Bangladesh.

As the flows increased, in Panama, the Guna Yala and Emberá-Wounaan indigenous communities began to charge for crossing their territories and for camping there, and transfer services in boats known as piraguas began to proliferate. The number of migrant nationalities also diversified. In this regard, one of the most notorious consequences was the integration of international human trafficking networks with local structures to "facilitate" the crossing through the Darien, which synchronized some routes and enabled new ones, including maritime ones, at high costs (Villalibre, 2015; Miraglia, 2016).

The fall of Turbo

In 2018, after the opening of a maritime service from Necoclí to Capurganá, the Turbo route lost momentum. The Necoclí route was shorter and safer, which led migrants to start using this route. The catamaran-type boats operated from 07:00 to 17:00 hours, with two types of departures: some for locals and tourists and others for migrants, who had to pay a round-trip ticket, even if the return trip was not necessary (information obtained in interviews).

In terms of cultural changes, local inhabitants commented on how some of the area's traditional trades began to disappear because the population saw migrants as a safe way to earn income. Thus, old trades were quickly replaced by new roles such as boatman, boatman's assistant, jungle camping salesman, puntero, facilitator, coyote, guide, or bag and provisions loader.

On the other hand, the routes to cross the Darien changed regularly for various reasons; among the best known and busiest were the following:

- Turbo-Capurganá-El Cielo-Armilla-Anachucuna-Canaán Membrillo-San Vicente.

- Necoclí-Capurganá-Carreto-La Llorona-Canaán Membrillo-San Vicente.

- Turbo-Acandí-La Bandera-Come Gallina-Bajo Chiquito-Lajas Blancas.

- Necoclí-Acandí-La Bandera-Come Gallina-Bajo Chiquito-Lajas Blancas (see Map 7).

For migrants, all routes involve a considerable economic investment and long journeys with extensive treks ranging from three to six days, transfers also in boats and canoes and, finally, in Panama's Senafront buses. Additionally, according to testimonies, since 2014 criminal and human trafficking groups established a practice of extortion of migrants that involved the payment of taxes, vaccines or collaborations, known as "arrival tax, security and guide payment and departure tax".

As a result of health measures taken during the covid-19 pandemic and the closure of border ports in Ecuador, Colombia and Panama, Senafront estimated that more than 25,000 migrants, mostly of Haitian origin, were stranded in Turbo, Necoclí and Capurganá (Corbino, 2021) until August 2021, when the reopening of the Panamanian border raised hopes of continuing the crossing. However, the Panamanian government was willing to admit only 650 people per day, which provoked pressure from Haitian and Cuban migrants in particular, who accused local leaders of lack of sensitivity. The authorities' response was that, as of October 2021, Acandí was listed as the new border control and crossing point.

From there to the border with Panama the route involves a walk of approximately eight hours. Then, to reach the town of Bajo Chiquito, a new journey begins from an altitude of 50 meters, crossing rivers and swampy areas through a rugged geography, until reaching an altitude of 1,000 meters, with significant climatic variations (see Map 8).

According to the people interviewed, the most difficult stretch to cross is Panama. Ana, who had left Ecuador with her family a month earlier because "there is a lot of violence [...] there are extortionist mafias, vaccinators [...] who threaten you, send you a paper and tell you that if you don't give them the money they will burn your business or kill you", explained that to get to Bajo Chiquito they walked "from 6 in the morning to 6 in the afternoon, not stopping walking on the Panama side".

In the interview she shared that in Panama they faced the greatest risks. For her:

It is worse than in the jungle, because in the jungle at least there is food, there are skittles, there is passion [...] but when you pass the Panama River it is terrible [...] there is water, but that water is contaminated water and you cannot drink it, and if you go without water you cannot get to Bajo Chiquito, which is a place where there are pure people, like Indians (interview, Ecuadorian migrant, September, 2023).

A 30-year-old Haitian immigrant who crossed through that area at the end of 2021 recounted his experience on that journey:

Before entering Panama you have three very high mountains, a first one of three hours, a second one of four hours, going up and down, and the third one even higher of six hours. Then comes the hardest part. I start climbing at noon, at 6, 7 in the evening you reach a very big rock, the fatigue exhausts you. You have to go down and look at the black jungle, you have to cross a rock that they call the "hill of death" because if you fall, you die. Below there is more jungle and you have wild animals. After that you have to get to a river, people follow this river for three days until they get to the first refuge. In those three days the most dangerous part begins because it is raining and the ground is very muddy, you have to hold on to the trees to sustain life; there you have no way to sleep, you go like a zombie all the time, it looks like a death zone. At dawn everyone leaves on a path with a lot of undergrowth. The first ones to leave mark the path with clothes and using machetes to know where to go, because you can die and disappear. Then hell begins because you can't eat, drink water or rest, you can't sleep, and you also have to watch out for bandits who rob and kill you. Your spirit needs energy, you have to be like a wild animal [...] sometimes you have to abandon the people who accompany you. After that follows a dangerous river, the current crosses with rafts [...] I had to watch children who were swallowed by the river [...] they disappeared. Arriving on the Panama side there is a real hell, there you start to see the dead in the river [...] you can smell the dead. At the first stop you start to breathe a little, everyone is thirsty, you have to wait until a good source comes out to drink water and not drink the contaminated water from the river. When you see the horizon, you are close to arrival (interview, Haitian migrant, December, 2021).

Even knowing what the interviewees reported, in 2021, 83,000 migrants of Haitian origin crossed the Darién through Acandí and their experience was crucial for those who followed this route. The choice of the jungle route depends to a large extent on the economic resources available, as local guides and the so-called "coyotes" offer services whose danger varies according to the cost. For this reason, some opt for boat transport, while others choose more arduous land routes, such as the Acandí route, which has been defined as the most extreme and dangerous, also known as "the Haitian route" (Clot and Martínez, 2018; Cárdenas, 2021).

In 2022 the number of crossings practically doubled with respect to the previous year. The Panamanian Migration Service registered the entry of 248,284 irregular migrants, of which 70% were from Venezuela, followed by people from Haiti and Ecuador, the latter as a result of a new stage of political and economic violence in their country. Another important fact is that after that year, the number of Cubans crossing decreased because they changed their route and began to travel by air to Nicaragua, avoiding the Darien crossing (Hernández, 2023).

The massive arrival of Venezuelan migrants became evident, and young families, single women or women with small children, single men, non-binary population, unaccompanied minors, groups of neighbors and co-workers were more frequently integrated. These made up contingents of thousands of people and were joined by others who re-emigrated from Argentina, Chile, Brazil and Peru. In October 2022, the flow of Venezuelans exceeded 150,000 people (Senafront, n.d. A) (see Map 9).

Generally speaking, the migration routes are controlled by criminal organizations that act as security guarantors from Turbo and Necocli, and their dominance extends all the way through the jungle to the Panamanian border. The shortest crossing through the Darien takes between four and five days, while the longest takes between eight and twelve. In Necoclí, the beach has become a vast reception camp for hundreds of migrants waiting for a place to continue on to Acandí and Capurganá. The wait can last from a week to ten days. Early in the morning, boats with 60 and 80 passengers, mostly migrants, leave the three docks of the place to navigate the gulf of Urabá. Upon arrival in Acandí or Capurganá, they are transferred by the same groups that control human trafficking to camps or shelters.

In Turbo and Necoclí they are offered transfer, guide and security services at an average cost of US$340 per person, which covers the payment to cross the Gulf of Urabá, one or two nights' accommodation without a bed in a camp, a light lunch, transfer to the second camp, security and guide to the Panamanian border. Once payment is made, they are given a pair of bracelets that they must wear at all times. Upon arrival at the first camp, migrants must hand over their identity documents or passports, which are verified in a system to which these groups have access. If everything is in order, a sticker is affixed to each document, which serves as certification. No migrant may arrive at the border without having paid this fee.

The fees for such services vary according to the nationality of the migrants and, according to their accounts, range from US$2,000 to US$5,000 per person. In addition, as part of the modernization of the services provided by these organizations, the Capurganá and Acandí camps began to sell - at high prices - food, cold drinks and airtime for cell phones, services that only some people could afford.

A Venezuelan migrant who made this journey with her husband and three children shared the following with us: "We were very hungry and thirsty all the way [...] if the governments pay attention to you because of your universities, I would suggest that, please, at every border crossing point, they place free food and water". Regarding the time spent in the jungle, she added that "it was either continue the journey or stay stranded [in the Darién] and eat" (interview, Venezuelan migrant, January, 2024).

The crisis worsened on October 12, 2022 when the United States announced its decision to reject Venezuelan migrants arriving by land at its southern border, which caused great confusion. Taking the next step became difficult, as one had to decide between moving on and getting stuck in Panama or some Central American country or returning to Venezuela (Piña, 2022).

In Necoclí, three groups of migrants caught our attention. The first was made up of nine men and one woman, all from a poor neighborhood in Valencia, Venezuela. They had organized themselves to make the trip and to that end they sold their cars, household goods and tools; some took out loans, others managed to gather resources through their relatives. On October 5, 2022, they met in Medellín, from where they boarded a bus to Necoclí. There they bought the necessary equipment and supplies to cross the jungle, and were on the verge of acquiring the so-called "combo", which included the payment of US$280 to cover the costs of sea transfer, guide services and the entry and protection tax in the jungle.

They were accompanied by a 17-year-old Venezuelan guide who had crossed the Darien three times and knew the route to the border at Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico. This young man drew them a detailed map of the route they would follow. However, the timing was not favorable for the group, as the news that the United States would close its border on October 12 made them reconsider their plans. Some sold what they owned to pay their way back to Venezuela and others looked for work in some city in Colombia; among them were cooks, mechanics, hairdressers and bricklayers.

The second group was a Venezuelan family of peasant origin, composed of a married couple with two sons, ages 18 and 16, and two daughters, ages 10 and four. Their dream was to reach the United States so that the older children could receive medical attention at the Shriners Hospitals, since both suffered from a deformity in their hands and had not received the care they needed in Colombia or Venezuela. Their resources were limited and they were engaged in fishing and food gathering. Unfortunately, their plan to migrate to the United States was cut short by Joe Biden's immigration policy.

The last group was made up of Venezuelan migrants who met upon arrival in Necoclí. Four were men between 20 and 40 years old, and two were families with small children. Together they set up camp on the beach, shared a fire pit and improvised a latrine. Thanks to the help of some nuns, they received provisions and shared their food. Two days after the news of the so-called border closure, this group decided to split up. Despite the difficult moment, Jorge and José, brothers-in-law who had been living in Colombia for a couple of years, did not want to turn back. They had managed to save enough money to undertake the trip; moreover, their faith was blind and "with invocations and prayers to the Lord Jesus Christ" they hoped to reach their goal.

The latter case was followed up. After a year of undertaking the adventure, Jorge managed to reach New Jersey, but his brother-in-law was less lucky. For him, crossing the Darien jungle represented the first challenge, and much of his success was due to seeking guidance on the route on social networks, mainly WhatsApp and TikTok. Jorge recounted how grueling the journey was, how he saw sick families and children, and how he experienced something that many people interviewed mentioned, "the smell of [the] dead."

Blue bags scattered in the undergrowth guided him along the way, where he met people of other nationalities and discovered how precious water was. He managed to reach Bajo Chiquito after four days of walking and, as best he could, he managed to get the money to pay for the canoe that would take him to the Lajas Blancas immigration station. Upon arrival, he was received by the military, who divided the group into those with tattoos and those without, which generated a sense of stigma and discrimination among the former.

Contrary to what the U.S. government expected with the tightening of its border, as of October 12, 2022 the migratory flow greatly exceeded the figures of previous years; even people of new nationalities, such as Chinese, joined. Months later, rumors circulated that Panama and Costa Rica would close their borders to irregular transit, which provoked another large migratory wave.

The facilities at the Lajas Blancas and San Vicente checkpoints, operated by Senafront and the migration agency in Panama, in collaboration with international organizations such as the International Federation of the Red Cross, the United Nations Children's Fund (Unicef) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), have been set up by Senafront and the migration agency in Panama.unhcr), continued to operate on a regular basis. The camps housed up to 2,000 people per day, of which only 1,000 were transferred to the Costa Rican border, who had to pay a fee of US$45 to US$50 for bus transportation from southern Panama to a camp in the north, near the Costa Rican border. It is at this connection point where Panamanian and Costa Rican authorities coordinate the process that allows migrants to reach Costa Rica (Senafront, n/d A) (see Map 10).

In Costa Rica, government agencies and international organizations provide migrants with food, shelter and basic medical care at the Temporary Attention Centers for Migrants. These measures are intended to help them continue their journey to Nicaragua as quickly as possible. After eight hours by bus and a payment of US$40, they are transferred to Los Chiles, a canton in the province of Alajuela on the border with Nicaragua, with about 35,000 inhabitants, which has a basically agricultural economy. For many years, the crossing to Nicaragua was via the San Juan River, but it is now formally closed (see Map 11).

In Los Chiles, migrants are approached by guides, clandestine cab drivers and coyotes who offer options to travel eight kilometers to the Las Tablillas border post (see Map 11). During the rainy season, transit involves the payment of a fee. Some locals rent rubber boots for three dollars, others charge to clean the mud off migrants' feet, and others sell them lunches and drinks (see Map 12).

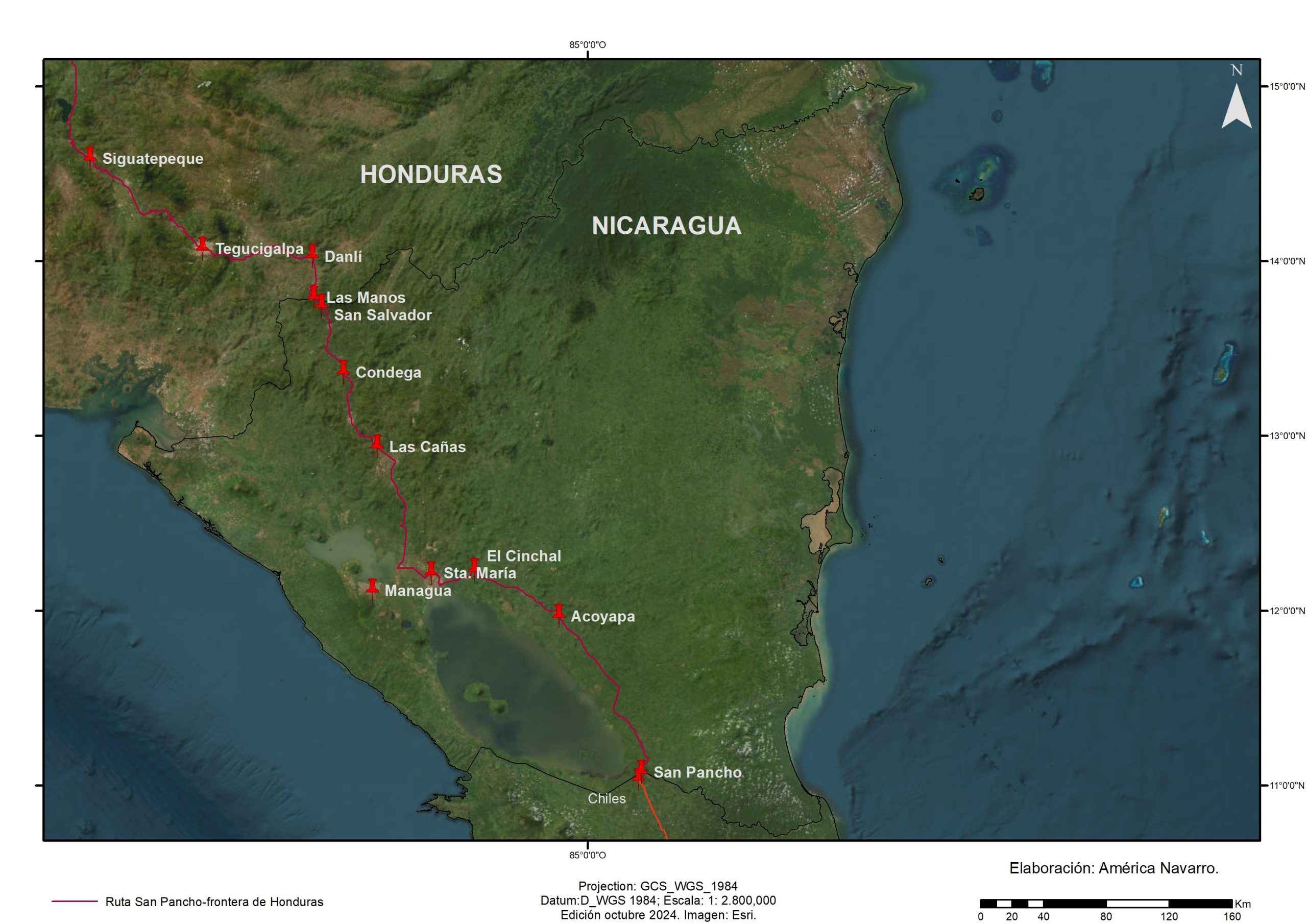

Unlike Panama and Costa Rica, which manage transit migration in a coordinated manner, Nicaragua lacks an official policy in this regard, so migration and police authorities act at their discretion. If a migrant wishes to enter the country through the border point at San Pancho, Nicaragua, he/she must pay US$150; otherwise he/she will have to cross through a trail, skirt a high concrete fence, walk through orange groves, and walk in search of unofficial transportation in the humid heat. Once through Nicaragua, the next challenge will be to cross the border into Honduras, where there is the option of doing it officially or clandestinely, depending on the economic resources available.

The route from Guasaule, Honduras, to El Salvador: transit through Central America's smallest country

The border crossing at Guasaule, Honduras, is a transit point for hundreds of Nicaraguan migrants who leave their country out of necessity and fear. Through what they call an "excursion", these migrants cross the Northern Triangle of Central America heading to the United States. Since the 2018 uprising, the economic and political situation in Nicaragua has worsened and has led to a large exodus. It is estimated that up to 40 buses with migrants arrive daily at the Guasaule post, of which 90% is Nicaraguan.

As in other borders, the use of "trochas" or "blind passes" is an alternative. Less than a kilometer from customs, the balsero business is flourishing. With a tire tied to a wooden frame, the balseros ferry people from one bank of the Guasaule, the river that marks the border between Nicaragua and Honduras, to the other; the charge for this service ranges between 20 and 30 lempiras (one to five dollars), while those who cross the river on horseback pay 100 lempiras. For food vendors, rafters and money changers, the Nicaraguan exodus represents a window of opportunity to generate resources (Hernández, 2023).

The entry of Nicaraguan migrants into Honduras is simple. The main bus terminal is located a few steps from the customs office, from where transport leaves for Choluteca, a town located 46 kilometers away. The next point is El Amatillo, port of entry to El Salvador. The time to cross Honduras is three hours. According to the National Migration Institute of Honduras (2022), between January 1 and October 23, 2022, 239,091 Nicaraguans traveled through that country.

El Amatillo, located in the department of La Unión, is El Salvador's first integrated border post. In October 2023, the facilities of this modern facility, which is operated jointly by the governments of Honduras and El Salvador, were inaugurated. Crossing is quick and easy, since people only have to show their travel documents -passport or identity card- when leaving or entering, while those who do not have them can enter by raft on the Goascorán River.

By bus, the trip from El Amatillo to San Salvador takes five hours, and from there the company Cóndor Internacional offers direct transportation to the Tecún Umán border at a cost of US$45 per person. A 22-year-old Salvadoran made the following recommendations:

The ideal is to travel with light luggage and book your tickets two days in advance. When you leave El Salvador, the odyssey begins. People do not have to change all the dollars into quetzales, at most a hundred. On the eight-hour road, the drivers are in contact with the police and generally at all points you are stopped and extorted, even if you are Salvadoran. You have to tell the police that you are going to the Quetzal refuge, that will give you some cover (interview with Salvadoran migrant, February 2024) (see Map 13).

For three decades, El Salvador has been a country of departure for emigrants to the United States; the transit of migrants from other countries through its territory does not represent a significant flow, as they usually enter Guatemala from Honduras.

Honduras: immigration restrictions and exemption from laissez-passer fees

Las Manos is the closest land border to Tegucigalpa. Migrants generally enter Honduras through trails, then travel in cargo vehicles and motorcycle cabs to Danlí, where they must process a safe-conduct for which they wait one to two days due to the high number of applications. Upon leaving the town, the first thing they do is find the "immigrant buses", old buses that offer low-cost services.

The trip from Danlí to Tegucigalpa is 160 kilometers and takes four hours on a narrow, bumpy road. Along the way, migrants encounter police or army checkpoints where they are asked for cooperation, which consists of contributions in lempiras or dollars. Despite this, migrants feel that Honduras is not a country that rejects or discriminates against them (see Map 13).

To get from Tegucigalpa to the border with Guatemala, there are three official border crossings. The most important are Agua Caliente and the port of Corinto; the road distances to be traveled are 300 and 370 km, respectively, although poor road conditions mean that transport takes up to six hours. At the port of Corinto, there are rigorous controls for entry into Guatemala, including biometric searches; however, as in other Central American borders, those who do not meet the requirements for official entry can enter through trails (see Map 13).

Guatemala: a difficult path for migrants

The town of Agua Caliente, Honduras, is for many the closest arrival point to Guatemala, where mobility conditions are severe. Throughout the day, the hustle and bustle of hundreds of people walking along trails to avoid crossing the border checkpoint can be observed. Once in Guatemala, the first goal is to reach Esquipulas, a key place on the route to the United States, where a complex network dedicated to human trafficking has been established. In the opinion of many migrants, crossing Guatemala irregularly without the help of a criminal organization can be dangerous (see Map 13). A 34-year-old Venezuelan woman commented that Guatemala was the country on the journey where she received the least attention. "In Honduras they gave us a safe-conduct to cross the country in five days and did not charge us anything. Here since we arrived we have not seen anything from the government, rather the police presence has resulted in a great robbery" (interview, Venezuelan migrant, October, 2023).

There is consensus among migrants that all of their rights are violated in Guatemala. Testimonies abound of women who reported sexual and psychological abuse when they were locked in rooms before the "law enforcement officers" let them leave for the Mexican border. Along this route they must cross several checkpoints, often preferring to walk through steep terrain to avoid being captured by the police or the army. At each checkpoint, the guards ask for contributions or bribes of between 10 and 30 dollars or the equivalent in Quetzals.

The fee for the transfer to the Tecún Umán border is US$300, which includes one or two nights' lodging, food, and transportation in a private vehicle in overcrowded conditions without the possibility of getting out. Another challenge is to avoid being detained by criminal groups, generally made up of armed men dressed in dark clothing who demand a fee per person or steal valuable belongings.

A young Venezuelan couple with a three-year-old son shared their travel experience in Guatemala:

At the border with Guatemala, Nanys became depressed and had no way to continue on the road. Going back was crazy. We were stuck for three days in Esquipulas until she recovered. By then we still had some savings left, with which we were able to pay the coyotes. The transfer through Guatemala was very uncomfortable, small cars with too many passengers, you could not get out to eat or use the bathroom, there were police checkpoints and criminal gangs, the drivers got off to negotiate with these guys, they used names or nicknames of people and passwords, then gave them the go-ahead to continue. About two hours before arriving at the Mexican border we took a bus to Tecún Umán. Leaving the terminal we were held up by some supposed guides, who tricked us and stole our cell phone and all our money. Although the border was close, we did not have enough money to pay for the river raft. The one who dared to ask for money was Edis. Thanks to the people who supported us we were able to get to Ciudad Hidalgo (interview, Venezuelan migrant, October, 2023).

But when arriving in Tecún Umán, whether on foot or by bus, there are other dangers, as one Salvadoran migrant reported:

I recommend that when you get to that town, if you are asked questions, do not answer more than what you are asked, do not ask anything to anyone, because from the moment you get off the bus, vultures fall from all sides. I recommend not to cross the river at night because at that time there are many kidnappings. If you are going to cross to Ciudad Hidalgo, I recommend doing it between 11 am and two in the afternoon because at that time people from Guatemala cross to Mexico to do their shopping. And also make sure they know the Waze driver because that disguises that you are a migrant. There are two options, one for migrants that skips the checkpoints and costs about 500 pesos or go on a normal combi, you get off before the checkpoint and walk around it. That way you only pay 50 pesos, but the driver will not take care of you if you are stopped. I recommend going without a cap, without bandoliers, without backpacks [...] and if God permits you get to the center of Tapachula. Once there I suggest looking for an Oxxo and buying a Telcel chip to communicate and save money (interview, Salvadoran migrant, October, 2023).

Mexico: Tapachula, the other stopper

The importance of Chiapas, and particularly Tapachula, in the reception of the migrant flow has its antecedents in the beginning of the new millennium. The train known as La Bestia (The Beast) boosted the mobility of the mainly Central American flow, from an environment characterized as dangerous, in order to cross Mexican territory and reach the United States (Casillas, 2008). In the last two decades, several authors have dealt with the subject, exposing the risks and violations of all kinds suffered by the people who used La Bestia. Gangs such as maras, groups of kidnappers and even officials of the National Institute of Migration (inm) incurred in acts that violated human rights, with women being the most vulnerable and exposed to risks (Ruiz, 2001; Casillas, 2008; Castillo and Nájera, 2016; Hernández and Mora, 2022).

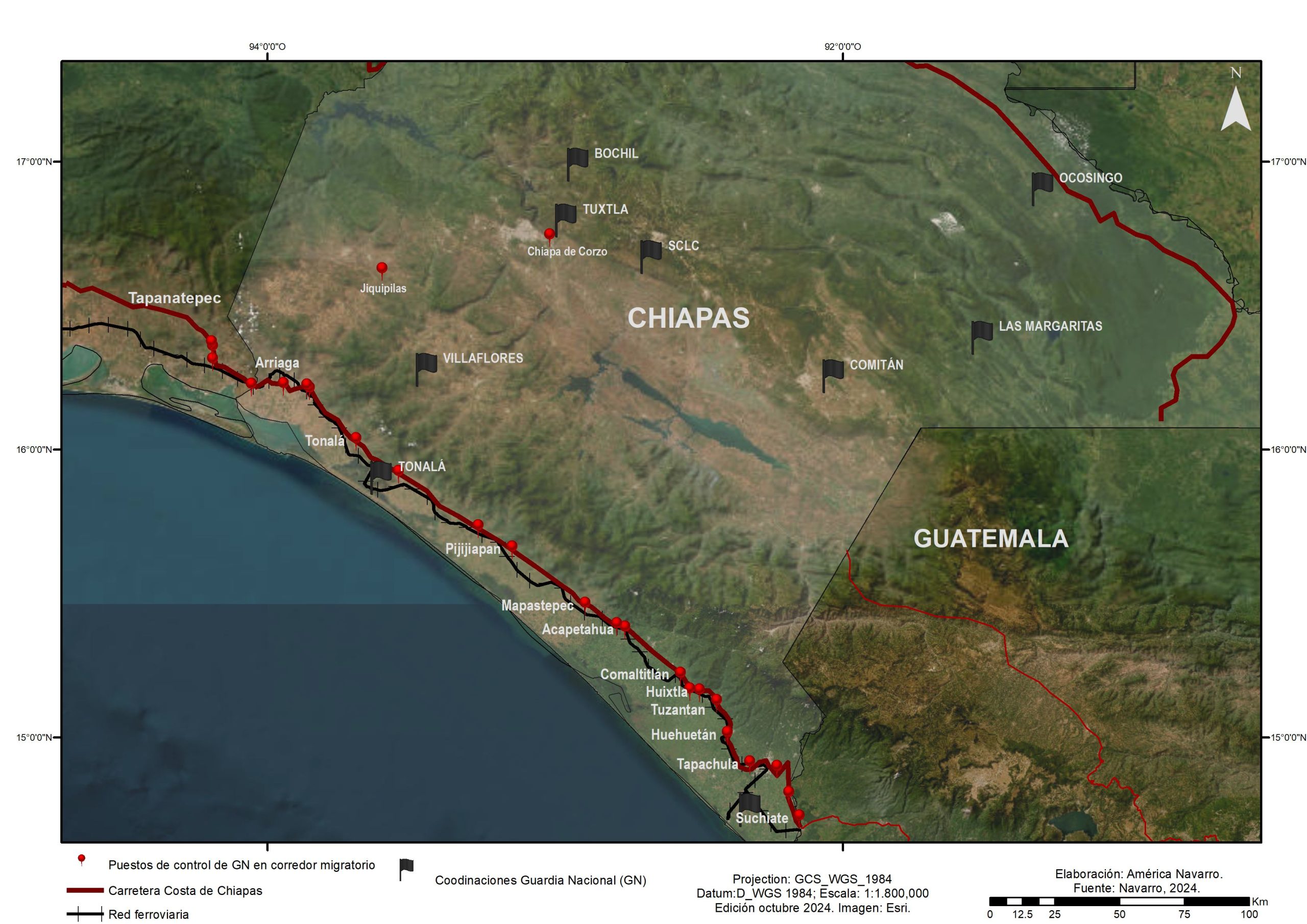

Understanding the complexity of Central American migratory routes through Mexico implies understanding that the train has been key in the migrants' journey, despite the economic costs and human risks it represented (Casillas, 2008) (see Map 14). Nevertheless, on September 20, 2023 this situation changed when the inmin alliance with Ferromex, announced the closure of 60 train lines.

Prior to that announcement, in January 2023, the Mexican government, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, announced that progress was being made on immigration issues with President Biden; specifically, it alluded to the fact that 880,000 visas and humanitarian permits could be applied for through a mobile application, cbp One, from anywhere in the world. The visas would be distributed as follows:

- 390,000 for Mexico.

- 164,000 for Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

- 326,000 for Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua and Haiti.

This provision contributed to the increase in flows, so over time the rules changed. On May 12, 2023, the U.S. terminated Title 42; however, Title 8 went into effect. cbp One starting in Mexico City, and thereafter in territories geographically located in the north of the country. These changes, in addition to the suspension of the train routes, were part of the pressure measures that the U.S. government, through the us Customs and Border Protection (cbp), ordered Mexico, through the Commissioner of the inmrepresentatives of the Secretariat of National Defense (Sedena) and the gnThe governor of the state of Chihuahua, as well as other officials, with the argument of "depressurizing" the northern border (inm, 2023).

These provisions had immediate consequences. During the field visit at the end of September 2023, it was possible to document how migrants interviewed in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Arriaga, Pijijiapan, Escuintla, Tapachula, Ciudad Hidalgo, in Chiapas, and San Pedro Tapanatepec, in Oaxaca, reported not only the impossibility for the train to continue to be their means of transportation while passing through Mexico, but also a series of returns from the northern border of the country, even with the appointment of cbp One assigned.

The migrants interviewed placed particular emphasis on the stalemates they endured for weeks and even months in bus terminals and shelters in different places, highlighting the long waits in Tapachula as a result of the initiation of the processing of any document that would allow them to transit "freely" through Mexican territory. This issue has been studied by authors such as Nájera (2022) and Jasso (2023), who suggest how Central American migrants -to which should be added a host of nationalities from South America, Asia and Africa-, in their passage through the national territory, have turned this city into a place of displacement and "prolonged stay".

In San Pedro Tapanatepec, young Venezuelans shared how being in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, five days before the interview with officials from the cbpwere returned by the gn to the southern border. The young people were dejected after weeks of waiting without being able to leave the place and faced with the obvious impossibility of obtaining a new appointment. We witnessed, through interviews and participant observation, many other stories that showed how the measures taken by Mexico practically implied a process of externalization of the U.S. border, and that the violation of human rights was a common denominator.

On the other hand, in December 2023, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid (comar) reported 140,982 asylum seekers in Mexico, of which 77,450 had sought refuge in Tapachula and 9,413 in Palenque; that is, 62% of the applicants, which shows the importance of Chiapas in receiving this flow. At the top of the list of countries of origin are the following: Haiti, Honduras, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Venezuela, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Afghanistan (comar, 2023). According to information obtained from interviews with officials of this agency:

In Tapachula alone, around 71 nationalities are present [...] it is in 2018, as a consequence of the migrant caravans, where a before and after in terms of the intensity of the international migratory flow can be located. In that year nearly 20,000 people arrived in Tapachula. For 2019 there were 72,000; in 2020, the flow decreased to 40,000 due to the measures taken in the face of the covid-19 pandemic; later, in 2021, 130,000 people arrived; in 2022, 118,000; finally, up to September 2023 the registry indicated 112,000, and we project around 150,000 to close the year. From September 15 to 30 alone, we attended to 19,671 people (interview, officials from comar, 2023).

As is common knowledge, migrants face waiting times that last weeks and even months, which has made Tapachula a bottleneck for entry into Mexico, a situation that has overwhelmed some service providers, such as transportation. The pressure in this city has reached such a magnitude that a sort of expansion of the bottleneck has taken place to contiguous municipalities along the Chiapas coast.

Makeshift clotheslines near shelters such as Viva México in Tapachula, open-air fires in Ciudad Hidalgo and hairdressing services in the streets, warned us about the process of stagnation that the interviews confirmed. The bus terminals in Escuintla, Arriaga and Pijijiapan were full to capacity, with entire families describing to us, more than the wait, their despair at the impossibility of leaving by official and safe means. In these places, where we also observed signs that read "only Mexicans", we interviewed people from Venezuela, Colombia, Cuba, Honduras, Ecuador, Haiti, Brazil, Argentina and Uzbekistan; many of them opted for clandestine transportation services, putting their lives at risk (Gómez, 2023).

It was possible to document that at the control points the gn allowed, in dribs and drabs, migrants to travel on foot, checking only those traveling by bus, from which they had to get off and continue on foot. This forced them to walk along the edges of the Costa-Soconusco highway in Chiapas, on their way to San Pedro Tapanatepec, Oaxaca, enduring temperatures above 38 °C (see Map 15).

Of the cases documented in this investigation, only five made it to the United States. One of them was the Narín family, who entered Mexico through the Suchiate and were stuck for more than a month in Tapachula. From there they were able to reach Matamoros, on the northern border, but were returned to Villahermosa. With discouragement, but great faith, they resumed the march from Tuxtla Gutierrez following the Cintalapa-Arriaga-Tapanatepec-Tehuantepec route. They worked for a few weeks in Tehuantepec, and then headed to Oaxaca and Mexico City, where they stayed for a couple of weeks. The Narín continued on the Saltillo-Monterrey route, where they got jobs, and then traveled to Ciudad Juárez to interview at the cbp. Finally, they entered the United States as refugees through Denver. Their journey involved six months of stalemates, with successes and misfortunes on their way to reach the longed-for "American dream".

Final thoughts

The study of the corridors and routes of displacement from the Darien Gap to Tapachula, from interdisciplinary perspectives, has been interesting. Through the cartographic representation of information from different sources, it was possible to interpret the traces of both traditional and new routes, crossing methodologies from the geographic and sociological disciplines, through new cartographies that turned the territory and the landscape into witnesses of the facts.

The cartographic visualization and the geographic and sociological analysis of the migratory routes and corridors made it possible to identify the territory involved and to weave a discourse that links the economic, political and social context with the space where the displacements occur, in order to reflect on the importance of the physical environment in explaining these movements. The spatialization of the long displacement of migrants made it possible to show, at first, the adverse conditions of the physical environment they face in the crossing of the Darien, on the Colombia-Panama border, to later continue to overcome adversities with border authorities and organized crime groups from Colombia to Mexico.

In Mexico, the geostrategic position of Chiapas, added to its commercial connection through the Pacific and the Atlantic, is changing the border dynamics in the south and this has favored the presence of drug trafficking cartels and organized crime groups that dispute the territory, which implies the control of the border itself. This is a similar dynamic to that observed in other countries that expel populations, or rather, from where the population is forcibly displaced, mainly due to poverty and violence, as we were told.

In addition, in the cross-border area, both in the northern and southern borders of Mexico, the violence exercised by the military forces permeates, but not only them, but also, as mentioned above, members of drug trafficking and organized crime cartels, who control through terror strategies, such as disappearances, the routes, the costs of transportation and, in general terms, the border itself. Having erected checkpoints gps in the field trips, which were subsequently projected in the sigled to a paradox: how to explain that a flow moving through a highly militarized corridor is under the control of organized crime groups.

Spatialization made it possible to identify spatial patterns of coincidence and proximity of highways and, in the case of Mexico, also of railroads and police checkpoints. gn in the Soconusco-Costa region of Chiapas. Interviews and participant observation also revealed the perception of migrants and some local residents that Tapachula is a bottleneck city that imprisons the flow of migrants at different times. In addition, through the interviews it was possible to remotely follow up with the Narín family, who gave an account of the new routes that allow them to leave the Tapachula bottleneck and of the cunning they had to reach the United States using the same legal rules imposed by the country to the north.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their pertinent comments. The research was carried out in the framework of the projects "Forced displacements and transformations of indigenous territorialities in the southern border of Mexico. Chiapas 1970-2022", with funding from papiit-dgapa unamIA301424, and "Circuitos migratorios, tránsito y movilidad en las fronteras Colombia-Panamá y México-Guatemala, 2010-2023", Centro de Estudios Migratorios de la Universidad de los Andes.

Bibliography

Alimonda, Héctor (2014). “La problemática del desarrollo ambiental. Una introducción a la ecología política latinoamericana pasando por la historia ambiental”, en Neptalí Monterroso, Luis Alfonso Guadarrama y Lilia Zizumbo (eds.). Democracia y desarrollo en América Latina. Toluca: uaem, pp. 139-174.

Álvarez, Soledad, Claudia Perdone y Bruno Miranda (2021). “Movilidades, control y disputa espacial. La formación y transformación de corredores migratorios en las Américas”, Périplos. Revista de Investigación sobre Migraciones, 5(1), pp. 4-27.

Bermúdez, Daniel, Evelyn Betancort, Luis Gutiérrez y Gloria Morales (2023). “Propuesta para generar un corredor migratorio socioecológico en el Tapón del Darién”, Tlatemoani. Revista Académica de Investigación, 14(43), pp. 138-165.

Botero, Carlos (2009). “Los efectos dinámicos del puerto de Urabá”, Revista Politécnica, 5(8), pp. 9-25.

Cabrera, Ada y Jesica Carrillo (2022). “La selva o Tapón del Darién en disputa. Instrumentalización de la tensión entre la movilidad y el control migratorio en el actual contexto de caos sistémico”, en Ada Cabrera, Blanca Cordero y Eduardo Crivelli (coords.). El orden hegemónico contemporáneo del sistema-mundo moderno. Puebla: buap, pp. 89-132.

Cárdenas, Wilmer (2021). “Los olvidados deseantes del Darién en busca del norte”, Quaestiones Disputatae: Temas en Debate, 14(28), pp. 157-170.

Carreño, Ángela (2012). “Refugiados en las fronteras colombianas: Ecuador, Venezuela y Panamá”, Encrucijada Americana, 5(1), pp. 6-24.

Casillas, Rodolfo (2008). “La ruta de los centroamericanos por México, un ejercicio de caracterización, actores principales y complejidades, Migración y Desarrollo, (10), pp. 157-174.

Castillo, Manuel y Jéssica Nájera (2016). “Centroamericanos en movimiento: medios, riesgos, protección y asistencia”, en María Eugenia Anguiano y Daniel Villafuerte (coords.). Migrantes en tránsito a Estados Unidos. Vulnerabilidad, riesgos y resiliencia. Ciudad de México: colef/unicach, pp. 71-98.

Castro, Guillermo (2005). “De civilización y naturaleza: notas para el debate sobre historia ambiental latinoamericana”, Procesos. Revista Ecuatoriana de Historia, 20, pp. 99-113.

Ceja, Iréri y Jacques Ramírez (2022). “La migración haitiana en la región andina y Ecuador: políticas, trayectorias y perfiles, Estudios Fronterizos, 23, pp. 1-24.

Clot, Jean y Germán Martínez (2018). “La ‘odisea’ de los migrantes cubanos en América: modalidades, rutas y etapas migratorias”, Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital, 13, pp. 1-30.

Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (2023). La comar en números, septiembre de 2023. https://www.gob.mx/comar/es/articulos/la-comar-en-numeros-355058?idiom=es

Congreso Panamericano de Carreteras (1991). Carretera del Tapón del Darién. Bogotá: Ministerio de Transporte.

Corbino, Mariano (2021). “La frontera olvidada, el Tapón de Darién”, Boletín del Departamento de Seguridad Internacional y Defensa, 44, pp. 5-6.

Echeverri, Jonathan, Juan Ordóñez, Jorge Álvarez y Nicolás Bard (2023). “Reflexiones sobre la construcción del tráfico de migrantes en Colombia a partir del caso de Urabá”, Secuencia, 116, pp. 1-26.

Ficek, Rosa (2016). “Imperial Routes, National Networks and Regional Projects in the Pan-American Highway, 1884-1977, The Journal of Transport History, 37(2), pp. 129-154.

Gómez, Alejandro (2023). “Accidentes de migrantes en Chiapas 2023”, Diario del Sur, 2 de diciembre. https://www.diariodelsur.com.mx/local/accidentes-de-migrantes-en-chiapas-2023-11089325.html

Hernández, Alberto (2023). “Nicaragua y la lucrativa ruta migratoria”, Latinoamérica 21. https://latinoamerica21.com/es/nicaragua-y-la-lucrativa-ruta-migratoria/

— y Carlos Ibarra (2023). “Navegando entre dominación y empatía: desafíos éticos y metodológicos en la investigación del corredor migratorio del Tapón del Darién”, Tramas y Redes, 5, pp. 29-46.

Hernández, Rafael y José Mora (2022). “Mujeres migrantes. Entre el desplazamiento y el tránsito precario por México”, en Rafael Hernández y Chantal Lucero-Vargas (coords.). Vulnerabilidad en tránsito. Peligros, retos y desafíos de migrantes del norte de Centroamérica a su paso por México. Tijuana: colef, pp. 85-124.

Instituto Nacional de Migración (2023). “Acuerdan inm y Ferromex acciones con 3 niveles de gobierno y cbp”. https://n9.cl/8q8ar

Instituto Nacional de Migración de Honduras (2022). Estadísticas migratorias. https://inm.gob.hn/estadisticas.html

Jasso, Rosalba (2023). Vidas truncadas: muertes de personas migrantes centroamericanas en tránsito por México. Ciudad de México: unam.

León, Alejandra y Alejandro Antolínez (2021). “Necropolítica y migración. Colombia y sus dos caras en la gestión de flujos migratorios transnacionales y transcontinentales”, en Necropolítica en América Latina: Algunos debates alrededor de las políticas de control y muerte en la región. Bogotá: uniandes-Programa de Investigación de Política Exterior Colombiana, pp. 87-97.

Luque, Arturo, Pedro Carretero y Pamela Morales (2019). “El desplazamiento humanitario en Ecuador y los procesos migratorios en su zona fronteriza: vulneración o derecho”, Revista Espacios, 40(16), pp. 3-13.

Miraglia, Peter (2016). “The Invisible Migrants of the Darién Gap: Evolving Immigration Routes in the Americas”, Council on Hemispheric Affairs, 18 de noviembre.

Miranda, Bruno (2021). “Movilidades haitianas en el corredor Brasil-México: efectos del control migratorio y de la securitización fronteriza”, Périplos, 5(1), pp. 108-130.

Nájera, Jéssica (2022). “Procesos de establecimiento de migrantes latinoamericanos recientes en la Ciudad de México: el trabajo como un medio esencial”, Notas de Población, (114), pp. 129-151.

Piña, Ingrid (2022). “Abandonados por los Estados Unidos: migrantes venezolanos llenan los vacíos en la comunicación de la política migratoria”. Proyecto de estudio independiente. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3662

Polo, Sebastián, Enrique Serrano y Laura Manrique (2019). “Panorama de la frontera entre Colombia y Panamá: flujos migratorios e ilegalidad en el Darién”, Novum Jus, 13(1), pp. 17-43.

Porras, Aleix (2023). “Repensando la respuesta humanitaria a la crisis del Tapón del Darién en el marco de los ods: el triple nexo humanitario en perspectiva, Análisis Jurídico-Político, 5(10), pp. 147-178.

Ruiz, Olivia (2001). “Los riesgos de cruzar. La migración centroamericana en la frontera México-Guatemala”, Frontera Norte, 13(25), pp. 7-41.

Schmidtke, Rachel (2022). Llenar el vacío: apoyo humanitario y vías alternativas para los migrantes en la periferia de Colombia. Informe. Washington: Refugees International.

Senafront (s/f). Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2010-2019. Informe de tránsito irregular por el Darién. Recuperado el 2 de diciembre de 2024 de https://www.migracion.gob.pa/wp-content/uploads/IRREGULARES-2010-2019-actualizado.pdf

— (s/f A). Extranjeros con estatus irregular y faltas a la legislación administrativa y penal remitidos por sexo: año 2022. Informe de irregulares detenidos. Recuperado el 2 de diciembre de 2024 de https://www.migracion.gob.pa/wp-content/uploads/IRREGULARES_POR_DARIEN_DICIEMBRE_2022.pdf

Angulo Severiche, Héctor, Óscar Casallas, María Isabel Granados, Natalia Herrera y Cristian Perea (s/f). “La cara de la migración de la que nadie está hablando”. https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/FOTOS2020/2019_h_angulo_et_al_migracion_de_transito_en_uraba_y_darien.pdf

Vilchez, Haydeé (2016). “Hacia una nueva diversidad: migraciones asiáticas en América Latina”, Tiempo y Espacio, 26(65), pp. 99-119.

Villalibre, Vanessa (2015). “Pesca humana. Captación de víctimas para la trata de personas en el contexto panameño”, Societas, 17(2), pp. 135-156.

Zamora, Anny Paola, Ángela Cecilia López y Paula Cristina Sierra (2008). Formulación de los lineamientos y estrategias de manejo integrado de la Unidad Ambiental Costera del Darién. Santa Marta: invemar.

America A. Navarro López D. in Geography from the National Autonomous University of Mexico. She is a full-time researcher at the Centro de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias sobre Chiapas y la Frontera Sur at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. unam. He is a member of the National System of Researchers, level i. She has been a professor at several sites of the unam and in postgraduate unach and unicach. Recent publications: "Fifty years of forced indigenous displacement in Chiapas, Mexico. From political-religious conflicts to conflicts between cartels", Journal of Latin America GeographyInternal forced displacement in Chiapas, a retrospective view from Geographic Information Systems, 2024" (you can–unam); "Construcción de una frontera al oeste del obispado de Chiapa y Soconusco. An approach from the sig-h (2023), Geographic Journal of Central America. Lines of research: frontier, forced displacements, sig oriented to the social sciences and humanities.

Alberto Hernandez Hernandez D. in Sociology from the Complutense University of Madrid. Professor-researcher of the Department of Public Administration Studies at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, president of that institution from 2017 to 2022 and visiting professor at the Center for Migration Studies at the Universidad de los Andes. National Researcher, level iii. He has been a professor in Colombia and Spain and a visiting researcher at the University of California, San Diego, and at the Instituto Universitario Ortega y Gasset, Spain. Recent publications: Hernández, A. and A. Campos-Delgado (coords.) (2022). Migration and mobility in the Americas. Mexico: Century xxi/clacsoHernández, A. and R. Cruz (coords.) (2021). Geographies of sex work in Latin America's frontiers. Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Lines of research: borders, international migration and cultural studies.