Mexicans in Exile and their political performance: a trench of resistance to the war on drug trafficking

- May-ek Querales Mendoza

- ― see biodata

Mexicans in Exile and their political performance: a trench of resistance to the war on drug trafficking

Received: February 19, 2018

Acceptance: July 4, 2018

Abstract

In this text I offer a reading of the role that the community can play in promoting the encounter between people who have gone through circumstances of terror. The material presented here is the result of two extended research stays in El Paso, Texas; one of four months in 2012, and the other of one year in 2014. During these stays, I conducted 19 in-depth interviews, participant observation and collaborative work with the organization Mexicanos en Exilio. Here I analyze under the approach of performance the complaint work that has been carried out by the organization; to propose that the membership has developed a political performance that, sustained in three reconnection processes (subjective, community and political) promoted by constant encounter and exchange, has allowed them to make their narratives visible and reach the international public sphere.

Keywords: collective, social knowledge, performance

Mexicans in exile and their political performance: trench-level resistance to the "war on drugs"

A reading of the role collectivity can play when promoting interaction between people who have moved through experiences of terror. The material here presented is the outcome of two extended research residencies in El Paso (Texas, US): a four-month investigation from 2012 and a year-long study in 2014. Over the course of both, I conducted nineteen in-depth interviews , completed participatory observations and collaborated with the organization known as Mexicanos en Exilio (“Mexicans in Exile”). With a focus on performance, I analyze denunciation efforts that have come from the organization, to propose its members have developed a political performance that — sustained through three reconnection processes (subjective, communitarian and political) and promoted by constant encounter and exchange — has afforded their narratives visibility and entrance onto the international public sphere.

Key words: Performance, collective, social knowledge.

Terror and silence: security strategy in Mexico

In December 2006 Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, then president of Mexico, declared that the fight against drug trafficking would be the main axis of his mandate. From that moment on, drug trafficking became one of the most pressing problems for the government and civil society (Maldonado Aranda, 2012). The first effect was seen in the orientation of the national security strategy towards combating said problem from a scheme known as joint operatives; In other words, it was a matter of deploying the national armed forces over specific regions in supposed coordination. The practical operation of the strategy led to serious conflicts in the regions where it was implemented because it resulted in the presence of three armed actors over the territories: 1. The police forces (federal, state and municipal); 2. The army and / or navy, and 3. Organized crime.

In this framework, it has been possible to observe an increase in the vulnerability of multiple actors and the number of precarious lives has grown. Let us add that, as time has passed, the actors that make up the structure of organized crime have appropriated the tactics of torture and deployment on the ground by agents of the armed forces, gaining the possibility of hiding through indistinction. There are multiple voices that point to the difficulty of differentiating between agents of the armed forces, the police and members of organized crime: they all use the same type of vehicles, the same clothing and are deployed over the territory in similar ways, when they are not identical.

The violence that has been unleashed in Mexico as a result of the war against drug trafficking is extensive and multiple actors are interconnected to carry out the practices that have the country submerged in high indicators of insecurity and countless victims. However, the analysis of the actors involved in the violent events is a complicated plot for the academic exercise since we work with circumstantial evidence. On this starting point, many of us choose to recover the notions proposed by Achille Membe (2011), who describes how war machines to "factions of armed men that split or merge according to their task and circumstances" and whose objective is to force the enemy into submission, through a dynamic of territorial fragmentation to make population movements impossible and divide the occupied territories through interior borders and isolated cells.

In the practical sphere, the difficulty in distinguishing the armed actors that manage the practices of terror in the territories has become an allegation from which the Mexican government tries to dissociate itself. However, the history of Mexico cannot be conceived without the illicit practices of the authorities and the political class. In Mexico, crime is carried out under an official mandate, it is the supreme act of governing (Domínguez Ruvalcaba, 2015).

Forced disappearences; executions on public roads; extrajudicial executions; blankets and written threats on the public highway; harassed and exhibited bodies on daily routes; These are just some of the practices of violence that have developed in the context of the war against drug trafficking. Through repetition and insistence, these practices are used to dismantle community meanings and silence communities. The practices of terror have a clearly identified strategic function, are carried out in specific time periods and fall on individuals whose ties in the community assign them a distinguishing characteristic: community leaders, human rights defenders or journalists, for example. Given that "each one of the dead of violence points towards the living" (Segura, 2000: 38), the reiteration has turned these practices into a pedagogical resource that establishes a knowledge in the population: terror.

These practices have developed over the last ten years and have led to the construction of a field of representations that favor the domination of territories; Violence has been used to attract public attention in the form of fear that later consolidates as terror. The circuits of violence have gradually diminished the ability to state events and the visibility of violent practices is aimed at producing what Taussig calls death spaces; places where endemic torture results in a silence that is imposed little by little until everything is enveloped. Through violence it becomes possible to control massive populations, entire social classes, even nations; Violent practices are at the root of the cultural elaboration of fear (Taussig, 2002).

Faced with the logic of disarticulation that underlies the practices of violence, the population has managed to develop knowledge that allows it to overcome terror by designing routes of action that, by multiplying, are tracing paths of resistance in the face of the logics of devastation. We are talking about knowledge produced from the fissures that terror opens, knowledge that indicates the emergence of a new subjectivity, suffering but subversive, that is taking shape in the peripheries of the hegemonic discourse.

Terror isolates and, in contrast, accompaniment allows people to generate resistance practices. Based on this premise, in this text I offer a reading of the role that the community can play in promoting the encounter between people who have gone through the same circumstances of terror. The material presented here is the result of two extended research stays in El Paso, Texas; one for four months in 2012, and the other for one year in 2014. During these stays, I conducted 19 in-depth interviews, participant observation, and collaborative work with Mexicans in Exile. In this text, I analyze under the approach of performance the complaint work that has been carried out by the organization; to propose that the membership has developed a political performance that, sustained in three reconnection processes (subjective, community and political) promoted by constant encounter and exchange, has allowed them to make their narratives visible and reach the international public sphere.

Performance political: trenches of resistance

In social sciences the metaphor of performance It is used to describe a set of bodily behaviors that develop in accordance with codes and conventions that frame them and allow their repetition. While the performance is an aesthetic practice that feeds on the interrelation between the visual arts and the performing arts, the term has been used in the social sciences to understand identity as performance, because “representation is our only access to being, because being who we are is obligatory and inevitable for everyone ”(Slaughter, 2009: 15).

The Spanish translation of this term covers a good part of this semantic field: perform = carry out, carry out, fulfill, perform, interpret, function; performance = interpretation, performance, function, session, operation, performance; performer = performer, actor / actress (Slaughter, 2009: 15).

The concept of performance and studies on performance they disrupt disciplinary boundaries and offer a route to understand everyday life from another place (Slaughter, 2009). Theories of performance among linguists, sociologists and anthropologists, they found useful tools for the analysis of the social in the metaphor of theatricality (Prieto, 2007), that is, beyond reviewing what the performance As such, in social sciences it is useful to think about what allows us to observe: each performance takes place in a specific setting in time and space, and involves an audience and a group of participants (Taylor, 2016).

I appeal to this analytical framework since I am inscribed in a tradition of social thought for which the concepts practice, action, process, situation, symbol and significance They allow the construction of a methodological view that incorporates the experience of the subjects. In this case, I describe acts that the membership of Mexicans in Exile performs repeatedly in specific settings and oriented towards specific audiences and through which they affirm a sense of belonging and their capacity for action.

That is, the people who congregate in the organization develop fragments of their experience to present it to specific audiences, and this process is what I observe under the metaphor of the performance. I propose then that performance It has been a resource used by the people victimized in the context of the war against drug trafficking to resist the techniques of production of terror, the performances they can become “a means to produce social exclusions and inclusions, update and legitimize certain mythical narratives or foundational stories, and delegitimize or suppress others, to imagine or create other possible experiences” (Citro, 2009: 35).

In the context of the war against drug trafficking, victimized people have had to learn mechanisms to place their narrative in the public sphere, to be seen by the media, so that their complaint is heard and considered, that is, to relate with the Mexican authorities. This accumulation of acts is what I call political performance: narrative practices that from the state periphery subvert the community fragmentation that is tried to produce through terror.

Among the many organizations that have been formed to denounce the abuses committed in Mexico throughout the war against drug trafficking, this text offers an analysis of the work carried out by Mexicanos en Exilio, an organization based in Texas, founded in 2011, that brings together 250 Mexican applicants for political asylum in the United States after being expelled from their homes and communities due to the multiple practices of violence. The political identity of the organization is quite clear, they are Mexicans who are in the United States to save their lives and have the possibility of continuing to demand justice from a government that has demonstrated its inability to enforce their citizenship, José Alfredo1 He indicates it in the following way: "more than fighting for a role, we are fighting for justice" (Holguín, president of Mexicanos en Exilio, personal communication, 2014).

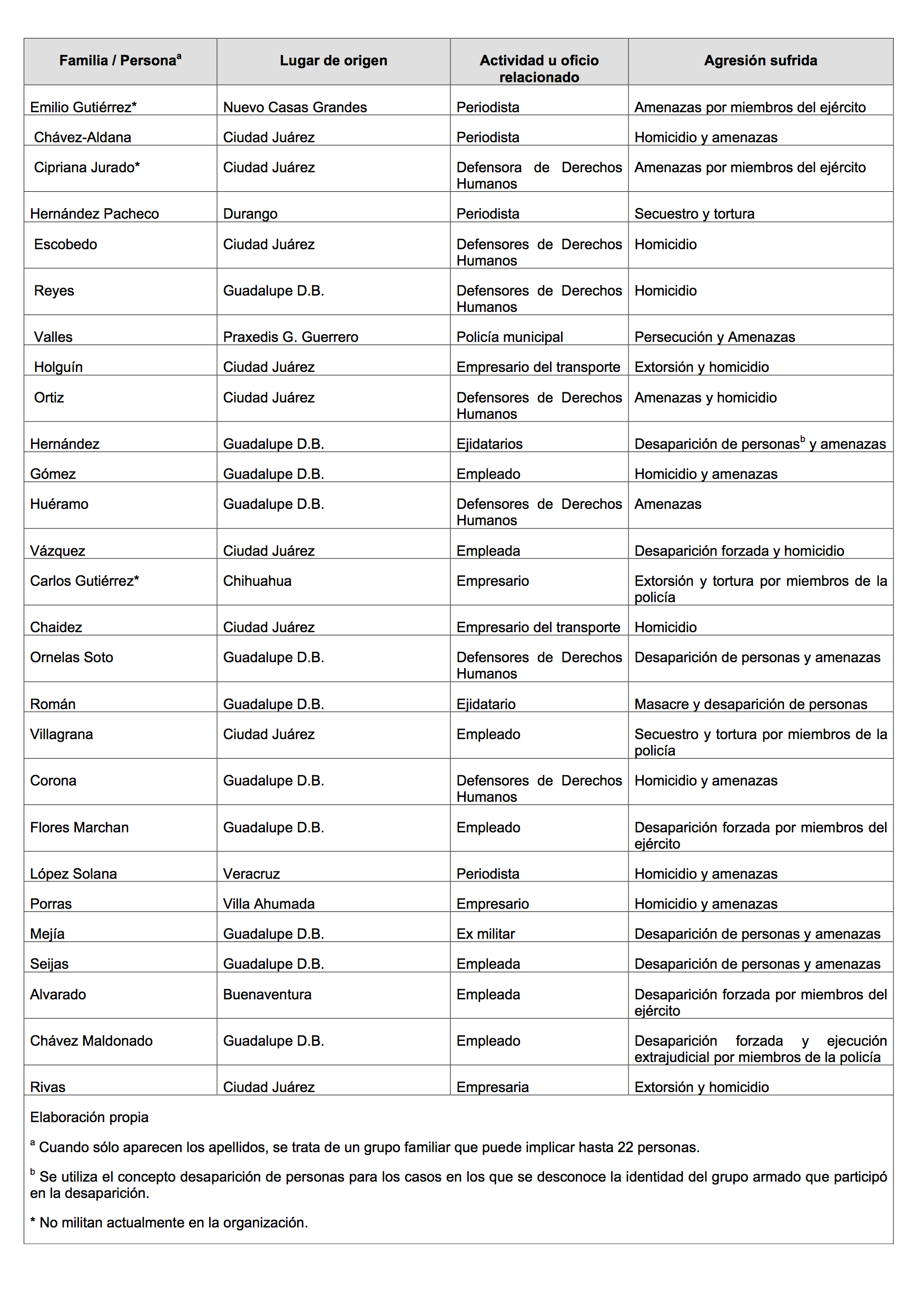

Given that the main characteristic of this group of people is to be asylum seekers, it is important to bear in mind that, first, the legal basis of an asylum request establishes that the person must have “well-founded fears of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion , nationality, belonging to a certain social group or political opinions ”(UNHCR, 2011: 11); Second, the membership of Mexicans in Exile (see Table 1) is made up of people who have suffered persecution in Mexico for two main reasons:

- In response to the complaints they filed for human rights violations within the framework of the security strategy implemented in the country since 2006 - better known as the war against drug trafficking. The threat was first directed at the complainant, activist or journalist, and later extended to their entire family.

- Under the format of the new forms of war - which are deployed from informality and with the participation of state and parastatal troops (Segato, 2014) - some member of the family nucleus was made a target of the negotiation mechanisms of the diffuse groups2 involved in conflicts and, little by little, the threat spread to the entire family.

The forms of persecution mentioned above were unleashed alongside the war against drug trafficking. The joint operations began in 2007 and as they spread over the republic, the population began to generate strategies to cope with the risks produced by the armed groups. In the case of Mexicans in Exile, 92,59% of the people in the organization are originally from Chihuahua, a state located in the north of the country, in the center of the international border between Mexico and the United States and in which the Operation was implemented. Conjunto Chihuahua from March 2008 to January 2010, when it became the Chihuahua Coordinated Operation, which implied that the federal government withdrew the command of the operation from the army to assign it to the Federal Public Security Secretariat (Silva, 2010).

As it borders the United States, Chihuahua has a strategically important location, particularly the Juárez Region —composed of Ciudad Juárez and El Valle de Juárez—3 Through which the local drug cartel, the Juarez Cartel, moved drugs through 300 dirt gaps to avoid police checkpoints through the municipalities of Cuauhtémoc, Villa Ahumada, Urique, Casas Grandes and Chihuahua. Due to its location, the territory of this region became a matter of dispute between the cartels, and it is stated that in 2011 “the Sinaloa Cartel managed to seize 90% from the most coveted area, the Juárez Valley” (Dávalos Valero, 2011 : 127). In this panorama, 11,240 deaths were registered in the public thoroughfare of Ciudad Juárez between 2005 and 2010 (INEGI), and until January 2016, 1,698 disappeared persons had been registered in the entire state of Chihuahua (Amnesty International, 2016).

Although I affirm that the victimization practices that have developed in the context of the war against drug trafficking are oriented by the objective of producing terror in the population, each victimization experience has given rise to a unique knowledge in witnesses and survivors ; This generates resources as “the practices performed and embodied make the 'past' available in the present as a political resource that enables the simultaneous occurrence of several complex processes organized in successive layers” (Taylor, 2009: 105).

As a matter of structure, in this text I only recover the practices and knowledge generated by the membership of Mexicans in Exile around the disappearance of people and forced disappearance, understanding the latter as

the arrest, detention, kidnapping or any other form of deprivation of liberty that is the work of agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by the refusal to recognize said deprivation of liberty or concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, removing them from the protection of the law (OHCHR, 2006).

Today, 7 of the 26 families that make up the organization still demand to know the whereabouts of their relatives and, through their narratives, it is possible to know the learning that the communities have developed in Chihuahua: when agents of a security group detain witnesses write down as much data as possible about the group in action to locate the person who has been arrested. Once the agents withdrew, the detainee's relatives went to the tactical group's operations centers and requested information from the person. These are the first search steps that we can hear in the narratives of the relatives of the disappeared who today congregate in Mexicans in Exile.

Later, in the journey through multiple instances and investigative agencies, the relatives of the disappeared persons found themselves with the same institutional mask: “The crime that you are reporting does not exist, present your case at the deputy attorney general's office. lost or absent people”(Alvarado, relative of the disappeared person, personal communication, 2014). In the case of Chihuahua, this type of response produced one of the first lessons that are recognized today by the relatives of disappeared persons “when a person is lost or absent there is no crime, no crime is prosecuted and thus they take the complaint so as not to make nothing ”(Alvarado, 2014).

Additional knowledge has made it possible for some cases to acquire greater visibility: family members in the search process began to approach human rights defenders to accompany them in the process. In this way, defenders who previously accompanied other causes (violence against women, obtaining social services, community rights) have begun a learning process to report and demand justice in the company of relatives in search. This tour led the Center for Women's Human Rights (CEDEHM) to support many family members in their complaints and search processes. This organization was founded in 2006 with the aim of representing, to empower and contribute to access to justice for girls and women who are victims of gender violence. When the Accusatory Penal System or Oral Trials System was implemented in Chihuahua in 2008 —first than in any other state — the CEDEHM was the first organization of Mexican civil society to litigate cases of gender violence in this new penal system. From the Chihuahua Joint Operation, the organization expanded the coverage of its services and since then has led the fight against the forced disappearance of people in the state (Quintana, 2016), a situation that, in the long run, has made it an ally fundamental for Mexicans in Exile.

It is in these routes where it is possible to speak of the conformation of political performance as a narrative exercise that questions the silencing of the security strategy and violence linked to organized crime in Mexico. Mexicans in Exile is a peripheral space both due to its geographical location - the organization's headquarters is on the border, in El Paso, Texas - and because of the type of people it congregates - asylum seekers inhabit a limbic environment to the extent in that their legal status does not give them access to the rights of any specific citizenship—; however, it has the power to promote a symbolic rearticulation in its membership. From here it can be considered as a trench, one of the multiple spaces of resistance against the security strategy.

Under the focus of performance, the knowledge has to be shared so that the performance in the scene flows and, for this to happen, the members of the organization have made a journey from their experiences lived in the singularity and even in solitude, towards the encounter with others similar to they. In this journey, people carry out reconnection processes with themselves, with the community and with a political objective, allowing the formation of the performance of the organization, which I have called performance politics.

Subjective reconnection

The reconnection that is brewing on the subjective level is the most unique and has allowed asylum seekers to rework the connection with their own history. Narrating to explain to others implies an exercise in ordering the facts and the translation of one's own feelings. Although each participates in public events from their subjective possibilities, being present at meetings, protests and public complaints has offered them a space to rearticulate their narration. Accompaniment in the exercise of listening to the other, in the midst of one's own pain, acquires a pedagogical meaning. In the words of José Alfredo Holguín:

It is sad to learn from the pain of others. I never thought I would find myself in this situation and even less share this pain, I am with people who managed, through pain, to change their life (Holguín JA, personal communication, 2014).

It is not a minor thing. Pain is an “anomalous and hostile presence that bursts into us to brutally impose on us the evidence that we are no longer who we thought we were […] It has the arrogance of fatality” (Kovadloff S., 2003), but in the encounter with others there is a self-recognition that, in philosophical terms, leads to suffering. Suffering, says Santiago Kovadloff, enables the constitution of the person, emerges from an operation that gives meaning to pain. In other words, pain is experienced individually and imposes itself on the individual, oppresses him; in contrast, suffering emerges when the individual turns towards others and allows himself to meet in and with them. This is what María de Jesús Alvarado points to4 when he tells us

With others it is sharing your same pain as you identify yourself by thinking that you have already gone through that. I thought that the worst had happened to me and you see that Doña Ema arrives devastated by her four children, her husband, her son-in-law, her grandson. You say: "hey, how are you still standing?" If I, with mine ... I can't even see Doña Ema, how she came to the CEDEHM and have supported her in all that and tell her that she has to be strong and share with her, hug her, be there. That has been very nice for us, it feels good to share that with someone who has happened the same, you identify a lot. At the same time it is joy, it makes you feel good (Alvarado MD, 2014).

Brief therapies —individual and group—, letters, poems, protest and public denunciation are some of the resources that the members of Mexicanos en Exilio have had to express and reflect on their experience and, from this, several have managed to travel from pain to suffering and reorganize his singular narrative. Here I consider it important to bear in mind that

the word "narration" does not necessarily refer to putting it into words. There are many ways to narrate. But whatever its subject, word or image, it is always a form of language, a language that tries to represent, make something understand, articulating its parts in a sequence, and that addresses a real or imaginary interlocutor (Wikinski , 2016: 54).

The case of Miguel Murguía is significant for understanding the subjective reconnection process. On August 14, 2011, he was brutally beaten by the group of armed men who took away Isela Hernández, his wife. Isela's family took him with them when they fled the town, they transferred him unconscious to the international bridge and he was admitted to a hospital for several weeks. From August 14, he not only had the absence of his wife and a pending application for political asylum in the United States, but the injuries also left consequences on his speech. In 2012 his narrative was choppy, and the thread of the conversation could be easily lost, he suffered from migraines and as he spoke he insistently passed his right hand over a scar left by the attack on his forehead.

Miguel has attended all the protests of the organization and little by little he regained confidence in his voice; now he asks to be considered as a speaker and prepares for it, prior to the conferences he writes a script of what he wants to say and leans on it if he loses the thread when it is his turn to speak. Miguel reestablished his ability to narrate aloud and, with it, every time he has the opportunity, he demands results from the Mexican authorities on the search for his wife.

Isela's kidnapping and disappearance appear as a traumatic event5 In the narrative of the entire Hernández family, in one way or another, practically the entire family was present at the event (with the exception of two sisters from Isela who lived in Tornillo, Texas). The group of armed men went through the houses of all the Hernández homes, looking for someone and, not finding him, they went to where the women of the family used to gather on Sunday afternoons. Isela, her sister Romelia, a sister-in-law, Diana and Gaby (Isela's two daughters), were taking the fresh air and chatting under a leafy tree. In a public display of their ability to coerce, the group of hooded men with weapons in hand demanded that the women put on their chests and tried to choose in a game of chance which one to take. Faced with this scenario, Isela asked that they take her away in exchange for not doing anything to her daughters.

The reconstruction of this narrative is the product of the articulation between individual stories of various members of the family, although none has the possibility of narrating the entire event, each one, from where they were, has a fragment of the event. About this type of circumstances Mariana Wikinski tells us:

Witnesses or victims could not construct the same story, even if they have been there, in the same place and at the same time, because in each one what happened has been linked to absolutely unique experiences, as their psychic apparatus was singular before what happened happened. And also because in all cases […] the opportunities to process what happened have been unique […] (Wikinski, 2016: 61).

The Hernández family has a constant presence in meetings and protests, but they prefer not to talk much about what happened that August 14. The space obtained with Mexicans in Exile contributes greatly to a work of collective symbolization in which each one connects from their uniqueness, and from there we can read the letter that Diana Murguía, Isela's eldest daughter, shares in the protests

When I learned to walk you helped me to the end, when I started dreaming you told me it's a great stage, when I started to grow up you told me don't be afraid to believe, when you know it's love you'll know that only someone will treat you better, when they get you [ sic] feel bad remember that you are special; when someone breaks your heart, don't let them take your illusion [sic]; when someone wants to hurt you remember that I will always be here! I MISS YOU MOM (Murguía, 2012).

Being with others enables movements on the singular, intimate level, one might say. Reporting in public requires strength and the ability to somehow articulate one's own story with the collective story.

Community reconnection

A second level of reconnection to which Mexicanos en Exilio contributes is that of the community. People who join the organization are faced with the possibility of ceasing to be a political asylum seeker who, alone, concentrates his energies solely on solving daily life in a foreign country.

The organization takes up the model that the Sanctuary Movement used during the 1980s to show itself in public spaces: refugees (or asylum seekers in this case) spread, among people dedicated to the defense of human rights, university students and organizations pro-migrants in the United States, information on human rights violations that occur in Mexico as a result of the war on drug trafficking. The political objective of this strategy is to generate empathy among the American progressive sector; that at the end of the 1990s he supported the protests that took place on the border to prevent the construction of a nuclear dump in Sierra Blanca (Rico, 1998) and that shortly afterwards he demonstrated against the Merida plan.

Under this scheme, Jorge Reyes Salazar, Daniel Hernández, Marta and Marisol Valles,6 and Alejandra Spector7 they joined the ranks of the Caravan for Peace on their tour of the United States in 2012; Later, the dissemination of Marisol Valles' story was allowed through the play “So Go the Ghosts of Mexico” by Mathew Paul Olmos in 2013, and the doors were opened to documentary maker Everardo González to portray Alejandro Hernández's exile Pacheco8 and Ricardo Chávez Aldana.9

From the Sanctuary Movement and other exile movements, Mexicans in Exile has resumed the relationship with the consulate as the scene of protests directed at its government, and it was there that they began to use their slogan, until today,: Exiles but not forgotten!

Advised by their legal representative, Carlos Spector,10 The organization has incorporated press conferences into its repertoire of practices, as a strategic resource for asylum seekers and a driving force for the organization. Until 2015, the conferences were held for two main reasons: 1) When new families join the group with the intention of informing both the Mexican government and American society that another group of people has had to escape the violence in Mexico. In this format, the objective is to point out to the media those directly responsible for the violence and "repeat to the authorities that we are here, we come here [to the United States] to follow up on our cases" (Holguín, field notes , 2014). 2) Events in Mexico related to asylum cases: these conferences focus on pointing out the prevailing impunity in Mexico.

The press conference is one of the scenarios in which the actors display their political performance. There is an audience both real - the spectators and readers of the media - and imaginary - the operators of the Mexican justice system and, ultimately, immigration judges in the United States. Under the focus of performance, the repertoire of collective knowledge is essential to stage a practice (Taylor, 2009), and press conferences come to fruition due to the prior, constant and structured dialogue that exists in the organization.

Once a month a meeting is called, usually on Sunday, at 10 am, since it is the day that most rest. The host house usually shares with the membership a drink (soft drinks or coffee) and sandwiches (pieces of sweet bread, fruit or more elaborate food, depending on the occasion). The meeting is always started by Carlos Spector11 to make a summary of the situation of the asylum cases that that month enter or have appointment in the Court. This activity is crucial, because the cases of each household and each family are at different administrative moments. Without the lawyer's explanation, people tend to interpret their case as longer than it should be or consider their case abandoned when there is no visible movement in their process.

Until May 2015 only 3312 of the 250 members had received legal protection status in the United States. The application for political asylum keeps the applicants in a prolonged legal limbo, they are not citizens nor are they considered residents; They are people with a permit that authorizes their stay within the borders of a country; in the United States they have to make regular visits to their asylum officer or the deporter, and every year (until December 2016) they had to renew their work permit. This turns the lawyer and his team into figures that are constantly present in the lives of the applicants. So explaining the administrative operation of the legislation allows the membership not to fall into despair and, through a translation exercise, the lawyer makes it easier for applicants to take ownership of their legal process. Carlos Spector is not only the legal representative of those who participate in the organization, over the years he has become a moral leader and in the monthly meetings, once he presented the legal report, he mentions the conjunctural circumstances in Mexico that may be related to a particular case and asks the membership to propose routes of action.

The first years of operation of Mexicans in Exile, Saúl Reyes Salazar13 served as moral leader of the organization and Cipriana Jurado14 she filled the role of official president. In September 2014, with a more consolidated base, the new board of directors of the organization was formed and José Alfredo Holguín began to serve as general president of Mexicanos en Exilio. Unlike Saúl and Cipriana, activists with a well-known trajectory in Ciudad Juárez and the Valle de Juárez, José Alfredo Holguín had no previous ties with the members of the organization, but instead gained their trust from the Detention Center,15 where he shared space with several of the members. Holguín describes himself as a “believer who has a lot of faith” and usually participates in the meetings with words that appeal to brotherhood: “each meeting serves to live together as if we were family, we are establishing family ties” (Holguín, 2014) .

In these meetings, the members express their fears regarding the events that are taking place in Mexico, they keep abreast of what is happening in their place of origin since several of their relatives still remain there. Thus, when a press conference is reached, the matter was previously consulted with the community, the possible consequences of the action to be taken were assessed and, to a certain extent, the words that will be put on stage when speaking were established. In the meetings of Mexicans in Exile, there are three voices that set the direction of the group, and this is how they express themselves when considering the possibility of giving a press conference

Carlos Spector: What do we do? How do we continue to denounce your disappeared? He is a disappeared person and cannot be forgotten, if we don't do something, nobody is going to do anything.

Martin Huéramo16: As we are low-ranking people, we need to be in a group so that our voice is heard. How is it possible that we are 30 or 40 families outside the town and the government does not know what is happening.

We have to denounce and denounce loudly. I know that everyone goes to Church, remember that Moses faced Pharaoh when the Bible was made public and everyone who had a Bible had to defend the word of God; this is similar.

José Alfredo Holguín: The government does not want to recognize the violence we are suffering, the greatest violence is extermination. The strategy is needed so as not to risk our lives here, nor that of family members there. We want to be very cautious and that everything is for the benefit of the group, we do not want to risk their relatives (field notes, 2014).

These types of comments guide the actions of the organization, the discussions that take place and the resolutions they arrive at constitute the area behind the scenes of the political performances. Here agreements are made and some differences are settled. In these dialogues and negotiations, a definition is formed as a community, in exile but all together and with a shared goal:

Our cases are correlated, we are telling the press, we have the advantage that we have Televisa, Univision here, and we are making it known internationally. In Mexico there is a violence that is palpable but invisible, the fact that they are finding the graves in Guerrero indicates the violence in Mexico. Every time we have a press conference, express your anger and pain […] (Holguín, field notes, 2014).

Cohesion as a group allows Mexicans in Exile now to link up with other organizations in El Paso, including the Border Network for Human Rights is one of its strongest allies. Its antecedents date back to 1990 with the founding of the Border Rights Coalition; Originally made up of a group of lawyers and civil rights activists, it changed its operations when Fernando García was hired as executive director. Under his leadership, the Coalition began to transform itself into a grassroots organization, that is, a process of training community members as promoters of human rights began; the objective was for the community to know how to face search warrants and to know their rights. On this basis, community members began training others and formed human rights committees. Finally, the Coalition acquired the name Red Fronteriza pro Derechos Humanos / Border Network for Human Rights (BNHR) in 2001 (Mejía, 2015).

The alliance between Mexicans in Exile and BNHR is woven in two ways. In practical terms, the target population of BNHR are migrants in the United States, the majority Mexican and many in an irregular situation, for which Carlos Spector is a fundamental ally, being clear that legal representation is done from his office and not by title. of Mexicans in Exile. Then, in symbolic terms, solidarity is extended to the extent that one of BNHR's main spokespersons is a relative of two people who joined the ranks of Mexicans in Exile in 2012.

Between the practical and the symbolic, in El Paso a link has been woven that allows Mexicans in Exile to relate to a portion of the receiving community and, at the same time, connects the exiles' demands with the struggle that migrants carry out in the United States. United. In the midst of this bond, in August 2014, the participation of Daisy, Paola and Sitlaly Alvarado germinated17 at the “100 Mile Border Walk for our Children and Dignity”.18

The walk was convened by BNHR and set the goal of raising awareness about the vulnerabilities experienced by migrants on their way to the United States, requesting comprehensive immigration reform, and rejecting the presence of the national guard at the US border.

Paola and Sitlaly started activism in 2010. The mothers' march in Mexico City was their first public participation and their first learning about the performance required by the world of activism: Two 14-year-old girls caught the attention of the media and surrounded them to tell their story

Paola: It was the first time we told about my mom's disappearance and everyone asked us questions and took photos, we ended up crying.

Sitlaly: My aunt started taking us because all the time we told her “take us with my mommy, we want to know where she is, we also want to look for her” (Alvarado, 2015).

After that experience, the psychosocial support work carried out by the CEDEHM allowed them to apprehend the narrative strategy required by the scene of the complaint: there the grievances are stated and the perpetrator is named but privacy is safeguarded. At CEDEHM Paola and Sitlaly, along with Daisy, their younger sister, participated in workshops that allowed them to meet young people with similar experiences to theirs and also received psychotherapeutic care. In such a way that when they entered the United States in 2013 they already carried a wealth of their own knowledge to insert themselves into a new scenario of complaint.

The three sisters attended the walk called by BNHR and throughout the journey carried out a contrasting exercise between the risky conditions to make the complaint, the rhythms of the protest and the solidarity that is built in Mexico. The 100-mile walk was carried out according to a strict schedule to culminate in three days, this involved a demanding pace and few breaks. Unlike the call that exists in the Mexican protests, where the first and last intention is to attract the largest number of people, the 100-mile walk was constituted as a closed event. When leaving Las Cruces (city established as point of origin), the coordinator of the line asked the people who had approached to provide their support to leave, as the walk would take a constant rhythm for which the members of BNHR would they had psyched up weeks in advance. The event was held on the base groups of BNHR and the media were invited to give coverage, but the lines were never opened to people in solidarity.

In the United States, the membership of Mexicans in Exile establishes a dialogue with a performance of different denunciation, other repertoires support a less prolonged and more peaceful display in the public stage, and in which the media play the role of the only public window towards the denunciation that is made, with the limitations that this entails:

Every time there is a new event, what we have been doing becomes opaque, for the media we know that our cases are a business. That is why we have to repeat to the authorities that we are here, we come here to follow up on our cases, all cases must be one for us (Holguín, field notes, 2014).

As José Alfredo Holguín tells us, these are new knowledge and Mexicans in Exile has managed to incorporate them to generate a political performance that, according to them, allows them to maintain their visibility.

Political reconnection: diasporic public spheres

So far we have reviewed the learnings that people have acquired in terms of the effect of their experiences However, the experience only becomes palpable once the individual has managed to reflect on their experiences and on the basis of this reflection endows their life trajectories with meaning and significance. Following this order of ideas, we can propose that the learnings of the membership of Mexicans in Exile have favored the elaboration of narratives that escape from the local to insert themselves in a global environment, what María Pía Lara names as diasporic public spheres (2003),

Pía Lara proposes that immigrants and exiles sow processes of globalized justice, which first requires the constitution of a global public sphere. This is developed in a reflective process that individuals develop about themselves and, as a result, they become capable of producing their own narrative. To the extent that it contravenes the hegemonic representation, when this narrative reaches the public sphere they begin to form counterpublics, and if it gains sufficient power it can obtain the public domain leading to institutional transformations of an emancipatory type (2003).

Pía Lara suggests that nomadic subjects are the vanguard in the constitution of the global public sphere, since through them two or more different geographical spaces are connected. These subjects are usually from peripheral towns or second class citizens that "occupy marginal positions and have been stigmatized by humiliation, discrimination and prejudice" (2003: 218). Migrants and exiles are those who, by demanding social justice, make up a diasporic public sphere, that is, a public sphere that exceeds the limits of national states and, at some point, can produce a global audience. We speak here of demands for justice at the international level that can generate awareness in world public opinion (Pía Lara, 2003).

As the performance politician cultivated by Mexicans in Exile over the years has managed to connect with complaint processes that transcend the limits of the local and national justice, appealing to transnational audiences. In this process, collaboration with the CEDEHM has been a cornerstone, since the litigation strategy implemented for the Alvarado case led to the exiles 'narratives being presented at the Permanent Peoples' Court and before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ( IACHR).

The Permanent Peoples Tribunal

The Permanent Peoples' Tribunal (TPP) is an ethical, non-governmental court of conscience that examines Human Rights violations and denounces them before international public opinion; It was established in 1979, recovering the experiences of the Russell Tribunal that judged US crimes in Vietnam (Astorga Morales, 2014), and the cases of Western Sahara have come before it (1979); Argentina (1980); Philippines (1980); El Salvador (1981); Tibet (1992), and human rights violations in Colombia (2006). Despite being a non-binding space, that is, its sentences do not produce legal effects, it is a space designed for victims to speak, it was thought of as “a mirror that tells people that what they live is true” ( Quintana Guerrero, 2013).

When the Mexico chapter was presented to the Court, seven thematic hearings were proposed to document the violations of fundamental rights in Mexico: 1) dirty war such as violence, impunity and lack of access to justice; 2) migration, refuge and forced displacement; 3) feminicide and gender violence; 4) violence against workers; 5) violence against corn, food sovereignty and autonomy; 6) environmental devastation and peoples' rights, and 7) misinformation, censorship and violence against communicators. To these was added a trans-thematic hearing on the destruction of youth and future generations.

Organized civil society has worked since 2011 to make the Mexico chapter of the TPP possible. Activists described it as an invaluable opportunity to make the country's dire situation known to the world. It was programmed and started before the international gaze was alarmed by the Mexican reality, that is, before the 43 normalista students from Ayotzinapa disappeared.

As convenors of the hearing "Femicide and gender violence", the CEDEHM extended the invitation to Mexicans in Exile so that Cipriana Jurado and Marisela Ortiz, activists against femicide who fled Mexico after receiving death threats, present their complaint at said hearing and that "the Nitzas19 they will participate in the Youth hearing, in Mexico City ”(González, field notes, 2014). In an internal meeting, Mexicans in Exile discussed the relevance of participating in this type of forum, but not from individual testimonies: “What we have been talking about in the organization is the need to make the organization more known” (Spector C. , field notes, 2014). In this way, it was agreed with the CEDEHM that the complaint of Mexicans in Exile would be presented in the "Women in War Situations" axis of the Femicide hearing and in the "Juvenicide" axis of the trans-thematic Destruction of youths hearing.

Structured as a Tribunal, the performance the space requires that the case be presented, that is, organizing the complaint narrative in an understandable way; However, as it is a space designed for victims to speak, it differs from other legal spaces (including migration) that seek to understand events in isolation. In this forum, it is requested to incorporate into the file an analysis of the context, not only data or journalistic notes of similar events, but also an explanatory exercise that locates the problem and puts it in relation to other events and that, if possible, shows patterns of victimization. To close this information, the complainant is asked to state the injury suffered and the reparation measures that he considers necessary. In addition to the file, on the day of the hearing each complainant or organization gives testimony. Due to these characteristics, critics of the criminal justice system consider that this Court is a space that allows the trial to be prepared without having the issuance of the pain as a priority, “there may be a trial […] without a sanction being reached. And not because the convicted are acquitted, but simply because the sanction may not be part of the logic of the trial process ”(Feierstein, 2015: 65).

The distance, the international border, their legal status and the threat that still hangs over their heads did not offer an opportunity to the members of Mexicans in Exile to attend the hearings in person, however, two testimonial videos were made so that their voice was present virtually. For those who gave testimony, it was an exercise of courage guided by an ideal of justice: their voice would be heard before an international court, their story could resonate in other spaces. The recording of both videos became a space for solidarity approach between the members, they listened to the stories one by one, advice was given and the usefulness of this space was recognized.

The inclusion of youth in this complaint process was particularly relevant. The information on young refugees in general, and Mexicans in particular, is scarce (Querales Mendoza, 2015), since the minority of age places this population sector under the shadow of family history, blurring their uniqueness and leaving them before legal procedures not designed for your specific needs (Courtis, 2012). With a space designated for them, each participant provided their narrative and placed in the testimony just what they are not allowed to say in other spaces.

Thus, Flor Marchan, an 18-year-old girl, came to the recording carrying the uniform of softball of his father —Rubén Marchán Sánchez, disappeared on March 18, 2012 by a group of armed men wearing military uniforms—, and when it was his turn to speak, he arranged the uniform on an armchair, took out a sheet of notebook that was folded in the pocket of his pants and read the following:

Diploma to the best father in the world for being always when I need you and teaching me with your example, what effort and work are, for caring when I get sick, for making me smile every day when I need it most, for talking to me about what Let it be, for teaching me, for understanding me, your love and good times. Today I want to give you this diploma; for being the way you are with me (Youth in Exile Video, 2014).

The fact of wearing his father's uniform to give his testimony constitutes in itself a narrative, a metaphor of absence, if that is how we want to see it. Flor did not describe the moment of the kidnapping or the pain caused by the disappearance, she wrote to the father with whom she hopes to meet again; his narrative unfolded on affection.

Diana Murguía, who also gave testimony in the video, took the space to comment on this, which is why few people have asked her: how her short life has changed since her mother disappeared:

She set a great example for me and is the best mom. I am sure that she would also have been the best grandmother and the best mother-in-law, although she could not meet her granddaughter and son-in-law because of the criminals who took her on August 14, 2011, her name is Isela Hernández Lara. After her disappearance, more memories came, you reach a point where you see that no one in your family will see for you as she did. Many times your own family, call it aunt, cousins, instead of supporting you, they harm you more with their expressions and ways of treating you, and even thinking about crazy things like suicide. It is also horrible to see that as the years go by, she is not here to see you and support you in your achievements, falls, disappointments, joys. For example, when you first change your life, friends, school and country because of the violence where you live, your life takes a 180 degree turn. Integrating into school is difficult because of the language, not knowing anyone and with the problem of not knowing where your mother is. For a year I left high school and because of the language I have not been able to obtain my diploma and it is frustrating that once you leave school you cannot have the diploma to continue studying or to get a better job (Video Young People in Exile, 2014).

In the midst of administrative procedures and the constant effort made by asylum seekers to adapt to the new country, the uniqueness with which young people face these processes is overlooked and this leads them to remain silent. Each of those who gave testimony for the Court took advantage of the space to stage the emotional impact that the refugee experience has generated on them. This is how Jorge Reyes puts it:

I came to the United States when I turned 18. Six of my relatives were killed in the Juárez Valley. It was a major change in my life, my mother was kidnapped and murdered in nineteen days. The life change I made was a very drastic change. I stayed from everything to nothing, I had to start a new life. I had to start with itself; to stand up for itself. I had to be tried and I am still tried in the courts as if I were a drug dealer, as if I was the worst human in history. I was detained for fifteen days for research, when all I did was study and be with my mother. They took a life ahead of me. They took from me the most valuable thing a human being can have, which was the mother. And here they come and treat you like you're nobody, like you're worthless. I believe that we are people and I believe that we are all worth equally (Young People in Exile Video, 2014).

The Peoples' Permanent Court became a listening space in which various daily silenced narratives managed to place themselves in the public sphere with the intention of generating an effect, of achieving some kind of justice. This is how Bishop Raúl Vera expressed it at the end of his participation in the Tribunal: "The governments bet on oblivion, we bet on memory [...] we do not forget, we do not give up, we do not surrender" (Vera, Hearing of the Permanent Court of the Peoples, 2014).

"We are all Ayotzinapa, we are all Alvarado"

A few days after the TPP concluded, on November 21, 2014, Carlos Spector accompanied Paola Alvarado before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. "The Inter-American Court is one of the three regional Courts for the protection of Human Rights, together with the European Court of Human Rights and the African Court of Human and Peoples' Rights" (IACHR, 2017). For a case to be accepted in this Court, it must first have been presented before the Inter-American Commission, the body in charge of “receiving and evaluating the complaints made by individuals on the basis of human rights violations carried out by any of the States Parties” of the American Convention on Human Rights (IACHR, 2017).

Paola Alvarado attended the Joint Public Hearing on the Alvarado Reyes et al. And Castro Rodríguez matters regarding Mexico;20 there the State's response was expected in compliance with the provisional measures21issued on May 26, 2010. Although at this point the case had not yet been accepted before the Court, the event shows us one of the international scenarios to which justice is appealed and that can be read under the idea of the public sphere global (Lara, 2003). Likewise, in this hearing we can observe the consolidation of a political position of the relatives of the disappeared in Mexico in the face of government inaction.

The performance in this Court it is different, unlike the TPP that only summons the voices of those who denounce, here a space is assigned to the State; to the Inter-American Commission; to the interested parties and their representatives and, finally, the Court, that is, the judges. The Mexican State presented itself to this audience with the speech that leads to any other performance space: the government is working. Almost a month after the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa, his intervention began by referring to the case; In the voice of Lía Limón, Undersecretary of Human Rights of the Ministry of the Interior:

We come to this public hearing at difficult times for Mexico in which our regulatory progress and institutional strengths have been questioned by the painful reality of the events that occurred in Iguala Guerrero. The Mexican State recognizes the seriousness of the disappearance of the 43 students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos rural normal school in Ayotzinapa, and has made an uninterrupted effort to search and locate them, as well as to guarantee a diligent, objective and impartial investigation that guarantees the rights to truth and justice as well as the punishment of those who are responsible. The dialogue with the next of kin and their representatives has been constant and various commitments have been assumed that are in the process of being fulfilled to guarantee the right of the victims to comprehensive reparation in accordance with the highest international standards (IACHR, 2014).

I highlight this performative display because since September 2014, "the 43" became a political reference for the issue of forced disappearance in Mexico. The days following September 26, 2014 were decisive in making the work of many groups of relatives of the disappeared in Mexico visible, who have turned to search for clandestine graves with their own hands due to government ineffectiveness. At the same time, it offered family members in search a moment of international visibility to demonstrate government inaction. The November Hearing before the Inter-American Court is a small-scale sample of the above and this was expressed by Alejandra Nuño, from CEDEHM:

On the night of September 26, the world witnessed the murder of 6 people in the southern state of Guerrero in Mexico and the forced disappearance of 43 normalistas. Since then they have been sought, as the undersecretary said, by sky, land and water. These actions, adequate and reasonable for the seriousness of the situation, are those that we would expect in relation to the 22,000 missing persons in our country, but especially in the case at hand, the only one that this honorable court has given Mexico a precise order. search for 3 people who have been missing since December 2009. The State should search day, night and tirelessly, diligently and by all means for Nitza, Rocío and José Ángel.

We are all Ayotzinapa, we are all Alvarado (IACHR, 2014)

These words express a feeling that permeates the universe of the relatives of disappeared persons, but that rarely reaches a stage of international justice administration. Despite the fact that the organization, search and complaint processes had been developed years ago, the relatives had not managed to generate a symbol that welcomed their struggle because one of the main characteristics of the people who disappeared during the war against drug trafficking has been anonymity; They have only been men and women with a name, a family and a job (Robledo Silvestre, 2017: 16).

No attempt is made here to analyze the mechanisms underlying the Inter-American Court, nor is a critical reading of the TPP proposed. Each of these legal and political reflection instances would imply a unique study. The intention in bringing them into this text is to show that the performance Political development developed by the membership of Mexicans in Exile converges in the conformation of a diasporic public sphere and, to reach it, people have had to reconnect with their history and with a community, recognizing themselves in the other is the basis of a political reconnection. To demand from the State the same attention they pay to a temporary case is to demand recognition.

The membership of Mexicans in Exile has been consolidating a performance politic throughout the years that today allows them to demand recognition. This was expressed on December 2, 2014 in a meeting with Eliana García Laguna, at that time head of the Human Rights Deputy Attorney General's Office (PGR):

Miguel Murguía: “Does there have to be a massive case for them to listen to us? Is it that our individual cases don't count? "

Ricardo Chávez: "I hear on the news of the 43 in Ayotzinapa, in Juárez there are thousands of murdered and disappeared and they do nothing, what certainty can we who are here have that something is going to be done?" (Meeting with PGR, 2014).

Once the political reconnection has been achieved, the membership always points towards the idea of justice; As Reyes Mate tells us: “We do not have to imagine the universality of justice exclusively as the universal validity of a procedure, but also as a constant rescue of frustrated lives, as an open process of saving forgotten stories or as an incessant response to demands for unsatisfied rights ”(2003: 114). Although in each of these instances a specific limit may be found, observing these processes under the approach of the performance it offers a possibility to think about the lessons learned that the forced disappearance have left behind, the complaints and the legal journeys that the family members have taken, even from exile.

Closing

Among the narratives of Mexicans in Exile we can find features of the constitution of a performance politician who has been formed in the periphery produced by the war against drug trafficking. In this periphery there are also the searchers who day after day have gone out to search in gaps and open fields the remains of their loved ones, those who do not give up on reviewing files to find information on disappeared persons, Central American mothers who cross the country in search of their children and the human rights defenders who accompany the complaints of the victims and relatives of victims.

Mexicans in Exile is just one of the spaces for accompaniment and resistance that have developed in the framework of the war against drug trafficking, although the forced disappearance and disappearance of people express the political will “not to leave a trace to make work impossible of the memory of future generations, turning the victims into specters ”(Ferrándiz, 2010: 175), walking alongside others and listening to them in the midst of their own pain has become a trench to face the security strategy in Mexico .

By participating in the organization, the membership has come into contact with the knowledge of performances concrete; the members of the organization who had been human rights activists or defenders, the lawyer and those who invoke the biblical words put their knowledge and practical knowledge into motion to generate cohesion in the organization and guide actions towards common objectives, thus originating their own expression performative, which I here called performance political. This performance It is sustained on three levels of reconnection in its members: a subjective reconnection that allows them to rearticulate their singular narrative; a community reconnection that allows them to build a joint narrative and that, a posteriori, allows a political reconnection. That is, due to the work in the organization, this group of Mexicans, expelled from their territory by violence, has managed to place their narrative and their demand for justice in the public sphere and, in some cases, they have had international reach.

Bibliography

ACNUDH (2006). Convención Internacional para la protección de todas las personas contra las desapariciones forzadas. Recuperado de https://www.ohchr.org/SP/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ConventionCED.aspx

Amnistía Internacional (2016). ‘Un trato de indolencia’. La respuesta del Estado frente a la desaparición de personas en México. México: Amnesty International Publications.

Astorga Morales, Abel (2014). “Caso ex bracero ante el Tribunal Permanente de los Pueblos”. La Opinión, 4 de octubre. Recuperado de http://laopinion.com/2014/10/04/caso-ex-bracero-ante-el-tribunal-permanente-de-los-pueblos/, consultado el 9 de marzo de 2017.

CIDH (2017). Historia de la Corte IDH. Recuperado de http://www.corteidh.or.cr/index.php/es/acerca-de/historia-de-la-corteidh, consultado el 11 de marzo de 2017.

_____(2015), Refugiados y migrantes en Estados Unidos: familias y niños no acompañados. Organización de los Estados Americanos. Recuperado de: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/informes/pdfs/refugiados-migrantes-eeuu.pdf, consultado el 25 de febrero de 2017

(2014). Audiencia Pública Conjunta de los asuntos Alvarado Reyes y otros, y Castro Rodríguez respecto de México en la Secretaría de la CIDH, 21 de noviembre. Recuperado de https://vimeo.com/112746581, consultado el 25 de febrero de 2017

(2000). Caso Bámaca Velásquez vs. Guatemala, 25 de noviembre.

Citro, Silva (2009). Cuerpos significantes. Travesías de una etnografía dialéctica. Buenos Aires: Biblos.

Courtis, Corina (2012). “Niños, niñas y adolescentes refugiados/as en Chile: un cuadro de situación”, en ACNUR, OIM & UNICEF, Los derechos de los niños, niñas y adolescentes migrantes, refugiados y víctimas de trata internacional en Chile. Avances y desafíos Santiago de Chile,pp. 51-89.

Dávalos Valero, Patricia (2011). “La Guerra Perdida”, en Raúl Rodríguez Guillén y Juan Mora Heredia (coords.), Crisis del Estado y Violencia Política social. México: UAM-A, pp. 150-171.

Domínguez Ruvalcaba, Héctor (2015). Nación criminal. Narrativas del crimen organizado y el Estado mexicano. México: Ariel.

Feierstein, Daniel (2015). Juicios. Sobre la elaboración del genocidio II. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Ferrándiz, Francisco (2010). “De las fosas comunes a los derechos humanos: El redescubrimiento de las desapariciones forzadas en la España contemporánea”, Revista de Antropología Social, núm. 19, pp. 161-189.

INEGI (2010) Censo de Población y Vivienda. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2010/, consultado el 26 de diciembre de 2017.

(2005). II Conteo de Población y vivienda. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2005/default.html, consultado el 26 de diciembre de 2017.

Kovadloff, Santiago (2003). “El enigma del sufrimiento”, en Manuel Reyes Mate, y José María Mardones. La ética ante las víctimas. Barcelona: Anthropos, pp. 27-49.

Lara, María Pía (2003). “Construyendo esferas públicas diaspóricas”. Signos Filosóficos, núm 10, pp. 211-233.

Maldonado Aranda, Salvador (2012). “Drogas, violencia y militarización en el México rural. El caso de Michoacán”. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, vol. 74, núm. 1, pp. 5-39.

Mbembe, Achille (2011). Necropolítica. Madrid: Melusina.

Mexicanos en Exilio, Jóvenes en Exilio, Video testimonial para el Tribunal Permanente de los Pueblos. El Paso, Texas. Recuperado de https://www.facebook.com/mexenex/videos/896417413786949/, consultado el 26 de diciembre 2018.

Prieto, Antonio (2007). “Los estudios del performance: una propuesta de simulacro crítico, en Performancelogía. Todo sobre arte de Performance y performancistas”. Recuperado de http://performancelogia.blogspot.mx/2007/07/los-estudios-del-performance-una.html, consultado el 10 de junio de 2016.

Proceso (2014). “Por niños migrantes, despliega Texas a la Guardia Nacional en la frontera”, 21 de julio. Recuperado de http://www.proceso.com.mx/377766/por-ninos-migrantes-despliega-texas-a-la-guardia-nacional-en-la-frontera, consultado el 7 de marzo de 2017.

Querales Mendoza, May-ek (2015). “Jóvenes en Exilio: más allá de la frontera después de la guerra contra el narcotráfico en México”. Ichan Tecolotl, vol. 26, núm. 304. Recuperado de https://www.academia.edu/19833156/J%C3%B3venes_en_exilio_m%C3%A1s_all%C3%A1_de_la_frontera_despu%C3%A9s_de_la_guerra_contra_el_narcotr%C3%A1fico_en_M%C3%A9xico, consutaldo el consultado el 9 de marzo de 2017.

Quintana Guerrero, Jaime (2013). “El TPP, es un espejo que le dice a la gente que es verdad lo que viven y que tiene razón en su lucha”, en desInformémonos, 24 de noviembre. Recuperado de https://desinformemonos.org/59257/, consultado el 9 de marzo de 2017.

Quintana, Víctor (2016). “Luces en medio de la violencia”, La Jornada, 9 de septiembre. Recuperado de http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2016/09/09/politica/023a2pol?partner=rss, consultado el 11 de octubre de 2016 .

Reyes Mate, Manuel (2003). “En torno a una justicia Anamnética”, en Manuel Reyes Mate y José María Mardones, La ética ante las víctimas. Barcelona: Anthropos, pp. 100-125.

Rico, Maite (1998). “México protesta por el plan de EE UU de instalar un basurero nuclear en la frontera”, El País, 5 de septiembre. Recuperado de http://elpais.com/diario/1998/09/05/sociedad/904946402_850215.html, consultado el 03 de marzo de 2017.

Robledo Silvestre, Carolina (2017). Drama social y política del duelo. Las desapariciones de la guerra contra las drogas en Tijuana. México: El Colegio de México.

Segato, Rita (2014). “Las nuevas formas de la guerra y el cuerpo de las mujeres”. Sociedade e Estado, vol. 29, núm. 2, pp. 341-37.

Segura, Juan Carlos (2000). “Reflexión sobre la masacre. De la identidad sin cuerpo al cuerpo sin identidad”, en Susana Devalle. Poder y cultura de la violencia. Ciudad de México: El Colegio de México.

Silva, Mario Héctor (2010). “PF retoma el control de seguridad en Chihuahua”, El Universal, 16 de enero. Recuperado de http://archivo.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/174842.html, consultado el 6 de febrero de 2018.

Slaughter, Stephany (2009). “Introducción”, en Hortensia Moreno y Stephany Slaughter. Representación y fronteras. El performance en los límites del género. México: PUEG-UNAM, pp. 11-18.

Taussig, Michael (2002). Colonialismo y el hombre salvaje. Un estudio sobre el terror y la curación. Bogotá: Norma.

Taylor, Diana (2016). Performance. Londres: Duke University Press.

___________(2009). “Performance e Historia”, Apuntes de Teatro, núm. 131. Santiago de Chile: Escuela de Teatro Facultad de Artes de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, pp. 105-123. Recuperado de https://repositorio.uc.cl/bitstream/handle/11534/4640/000539909.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

UNHCR (2011). Manual y directrices sobre procedimientos y criterios para determinar la condición de Refugiado. En virtud de la Convención de 1951 y 1967 sobre el estatuto de los refugiados. Ginebra: UNHCR. Recuperado de http://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain/opendocpdf.pdf?reldoc=y&docid=50c1a04a2

Wikinski, Mariana (2016). El trabajo del testigo. Testimonio y experiencia traumática. Buenos Aires: Ediciones La Cebra.