Lo prieto: Antiracism, sexogenic dissidence and self-representation in the work of two Mexican visual artists.

- Itza Amanda Varela Huerta

- ― see biodata

Lo prieto: Antiracism, sexogenic dissidence and self-representation in the work of two Mexican visual artists.

Receipt: September 22, 2024

Acceptance: May 02, 2025

Abstract

I will discuss from cultural studies the concepts of anti-racism,1 sexogenic dissidence and self-representation of racialized populations such as prietas from the work/word of Mar Coyol (State of Mexico, 1994) and Fabián Cháirez (Chiapas, 1987). Their works have been exhibited in different venues of Mexican high culture and in independent spaces. I present a discussion on the context of production, an analysis based on the artists' words and a reflection on racism, anti-racism, self-representation and cuir. The methodology was based on ethnographic observation in exhibitions and art shows of Coyol and Cháirez during June 2024 in Mexico City, semi-structured interviews with the artists, bibliohemerographic review and ethnography in socio-digital networks.

lo prieto: anti-racism, sex-gender dissidence, and self-representation in the work of two mexican visual artists

Drawing on a cultural studies perspective, this article explores anti-racism, sex-gender dissidence, and the self-representation of racialized populations as prietas [dark-skinned] in the works and words of Mar Coyol (State of Mexico, 1994) and Fabián Cháirez (Chiapas, 1987). Works by the two artists have been exhibited at major art institutions and independent galleries in Mexico. Besides delving into the context of their production, the analysis uses the artists' own words to reflect on racism, anti-racism, self-representation, and queer theory. It draws on ethnographic observation at Coyol and Cháirez exhibitions and shows in Mexico City in June 2024, semi-structured interviews with the artists, a literature review, and an ethnographic study of social media.

Keywords: anti-racism, sex-gender dissidence, race, lgbttiq+ art, self-representation.

Jewelry. I.1.f. Mx. Ridiculous object, corny.

Pop; 2. The act of a homosexual man who is extremely mannered. pop.

Dictionary of Americanisms of the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language

Introduction

In this text I will make an analysis from cultural studies with an intersectional view of the relationship between race, art, population, and the arts. lgbtq and political subjectivities. Therefore, I start from the explicitness of my work by situating it in the debates with bibliography and intellectual, artistic, political and academic works of people from the global south. This article works the notion of radical contextualization (Grossberg, 2016) to think the word and the work of the mentioned artists; in that sense it seeks an analytical work with ethnographic information and analyzes the context of production of the discourse on the prieto by reading as text the images and the interviews to both artists.

The decade of the nineties of the xx is consolidated in ethnicity studies as a watershed in the relationship between the State and the altered subjects and peoples in Latin America. Although the first century of the xx in different regions of the continent was marked by revolutions, dictatorships, invasions and armed movements, the Latin American states had placed in the altered populations different versions of public policies to constitute nations based on concrete ideas, especially those that sought to assimilate indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples into a modern and mestizo nation-state perspective.

By the 1990s, the autonomous indigenous movement, the recognition policies and the new forms of identity constitution altered at the margin of state policies would mark new organizational forms both for indigenous peoples and for the emergence of "new political identities", as is the case of Mexico, Chile and Bolivia with the appearance of the black/afro-descendant population.

What are the historical marks and the imprint of the aforementioned mobilizations on contemporary subjectivities? Perhaps a new epistemic framework from the second decade of the 2000s up to the contemporary moment is the boom of the studies and policies of racism and anti-racism in Latin America.

Derived from these new political discussions about what racism is, as well as its historical constitution in different Latin American countries, I am interested in thinking specifically about the case of Mexico in light of two important movements around racism: the first one is the conceptualization of the global north on racism and anti-racism as a source of inspiration for the urban political and intellectual environment in Mexico and in another moment, how that battery of knowledge contextualized in the United States will have a reception, elaboration and implementation in contemporary generations, as is the case of Mar Coyol and Fabián Cháirez in the field of artistic creation with a marked anti-racist accent in the visual discourse and political discourse. I only mention these two spaces in order to be able to enunciate them, although I do not see them in a separate way, what interests me is to give an account of these two spheres in relation to the political context of the works presented.

I am interested, moreover, in thinking about how the politics of racial-ethnic difference meet the recognition and affirmative policies of community lgbttiq+. That is, in terms of what we would call intersectionality; how there is an encounter between the different forms of diversity that inhabit and mobilize contemporary discourses.

Specifically in Mexico, the political movement of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (1994-present), the guerrilla struggles of the 1970s, the student movement of 1968 -including the Homosexual Liberation Front of Mexico-, as well as contemporary mobilizations such as the black-Afromexican movement, the migrant caravans, among other political mobilizations, are part of the foundations that make it possible to discuss racism from a more liberal perspective (such as the struggle for the rights of indigenous, black-Afromexican and Afro-Mexican populations), the migrant caravans, among other political mobilizations, are part of the foundations that make possible the discussion of racism from more liberal perspectives (such as the struggle for the rights of indigenous, black-Afromexican and Afro-Mexican populations, and the lgbttiq+) to positions that question how these perspectives have been co-opted by neoliberal multicultural policies:

The other denomination to be considered here is that of canned entities or identities of globalization. According to Segato (2007), globalization has led to the increasingly strong circulation of certain identity images in the media, in literature, in academia, in international technical cooperation, in state and supra-state discourses. Thus, some of these images begin to position themselves. This circulation is predominantly from some sides to others. Then movements and mobilizations begin to be pronounced in the name of these identity ideas, which respond to very particular logics, historical experiences and national formations of otherness. What Segato says is that historical identities -those that make sense and those that are rooted in national formations of otherness- enter into tension, in translation or in relation to these identities of globalization, sometimes to enhance them, sometimes to undermine them (Restrepo, 2015: 86-87).

It is at this historical and epistemic crossroads where I place this reflection on self-representation, art lgbttiq+ and the construction of the depriest in Mexico. I place it here because that is how we can see what are the reappropriations of an imperial notion of race and of a form crooked of the neoliberal politics of both otherness and sex-generic dissidence.

Audio description of the image: Against a background of blue skies, with white and pink clouds, with low mountains and in the middle of a cornfield, four upright people are standing, two more kneeling with red flowers in their hands and pink loincloths, their whole arms pointing to the outer sides of the image. The standing persons are in the center of the image next to a trans woman dressed in the typical clothing of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec: long skirt with ruffles, red huipil with colored chain, a necklace of red flowers, a pink headdress on her head; she holds a white lit candle in each of her hands, behind her, on her back she has a halo of alcatraces. She has on her skirt a text that says "Prietx sagrada". Two deprietx and femmes are holding a blanket with two sticks, the legend on the pink blanket says Mexico is racist and four other words: colonialist, murderer, classist and cissexist. The people are dressed in short skirts and sleeveless T-shirts, the one on the right in yellow, the one on the left in orange. The other two people standing are wearing shorts, the kind boxers wear: on the springs of the shorts it says: "negrx hermosx" and on the other person's "marronx bellx". There are two pink ribbons with letters at the bottom of the painting and they say "until oppressions are no longer possible" and the second one, "The State is not all of us".

I would call these forms of graphically and verbally enunciating what is deprive is what I would call specific exercises of counter-miscegenation:2 As the collective Marrones escriben points out in Argentina: "In short, to be Marrón is to be a community of people who meet in urban and rural neighborhoods and who recognize themselves as part of a colonial history that continues" (Identidad Marrón, 2021: 25).

An imperial notion of race

In the last 15 years -since 2010- three basic concepts for the development of this work have been widely discussed in Latin America: race, racism and anti-racism. In this section, I will focus on presenting them succinctly in order to constitute a common language throughout the text, and also to contextualize the readers in such debates, both academic and political.

For cultural studies and postcolonial criticism, the notion of race is useful as an analytical concept. Taking up the studies of key thinkers such as Aníbal Quijano, Stuart Hall, Rita Laura Segato, María Lugones, Max Hering, among others, we understand race as an analytical concept that allows us to think of modernity, capitalism and patriarchy as socio-historical constitutions of social classification that have concrete effects on people's lives; in this sense, we take up Aníbal Quijano's perspective:

Aníbal Quijano (Yanama, 1930-Lima, 2018) promoted the discussion on race in Latin American critical theory, an intellectual exercise that had an impact on postcolonial and decolonial thought in the continent. From the elaboration of his thesis on the coloniality of power, Quijano exposes that race is a form of domination that was inaugurated with the "discovery" and subsequent conquest of Latin America. Race, then, will serve as a device of domination to create and maintain coloniality and capitalism. With this premise, Quijano considers skin color one of the different elements that give meaning to social differentiation and classification, but it is important that in contemporary debates we are able to observe and analyze what are the other elements that constitute race as a mechanism of domination and racialization as its political practice and not only focus the discussion on pigmentocracy, but observe the historical and social phenomenon that constitutes and re-actualizes race as an analytical and ordering notion of the economy, politics and society (Varela Huerta, 2023: 245-246).

From a perspective based on English-speaking Caribbean thought, we can look at the notion of racial contract:

The racial contract is the set of agreements or meta-agreements, formal or informal [...] between members of a subset of human beings, hereafter designated by (changing) "racial" (phenotypic/genealogical/cultural) criteria [....] as "white" and coextensive (with due regard for gender differentiation) with the class of full-fledged persons, to categorize the remaining subset of humans as "non-white" and of a different and inferior moral status, subpersons, so that they have a subordinate civil position [....] the overall purpose of the contract is always the differential privileging of white people as a group over non-white people as a group, the exploitation of their bodies, lands, and resources, and the denial of equal socioeconomic opportunities for them. All white people are beneficiaries of the contract, even if some are not signatories to it (Mills, 1997: 28).

In other senses, the idea of racial formation (Ommi and Winant, 1994) and racial capitalism (Cedric Robinson, 2018) are productive to think with such authors about the different ways in which race, racialization and racism have been put under discussion in the social sciences; however, the theoretical proposal accompanies the political and aesthetic proposal of the artistic products exhibited here, with a clear position of discussion with the global south, with the ways in which we want to discuss from our specific realities what we understand by race/racialization/racism and, of course, anti-racism.

Secondly, the notion of racialization is linked to the practices and effects that the notion of race has on social subjects. As specific markers linked to the social organization of life, economy and even affections. The processes of racialization are inscribed in broad and diverse temporalities, which respond to the forms of state alterization, media production, social discussions at various levels, as well as to the symbolic production found in the public sphere. In this sense, Alejandro Campos argues the following:

The social process by which bodies, social groups, cultures and ethnicities are produced as belonging to different fixed categories of subjects, charged with an ontological nature that conditions and stabilizes them (see Banton, 1996). In plainer words, racialization is defined as the social production of human groups in racial terms. In this particular understanding, races are a historical social construct, ontologically empty, the result of complex processes of identification, distinction and differentiation of human beings according to phenotypic, cultural, linguistic, regional, ancestral, etc. criteria (Campos, 2012: 21).

Audiodescription: On a purple background, with green grass and the silhouette of a soccer player running, sits with his legs open, a young black-Afromexican, with his hair curly and black. His eyes are closed, as if in a dream, and his face is turned to the right side of the image. He is dressed in a soccer uniform: yellow and green jersey of the Brazilian national team, on his chest two yellow and white hummingbirds are biting the jersey at the nipples; light blue shorts, white knee-high socks, special blue soccer shoes. In the foreground is a ball punctured by a spear; the ball is deflated.

Based on the social classification and domination linked to the various forms of racism, some social subjects have carried out specific acts and exercises of anti-racism, both in the institutional political sphere, in the community political sphere and in areas as diverse as school classrooms, in the streets of towns and cities, in art galleries, in dance and concert halls, in academia, in the spaces of national and supranational state policy, as well as in the large global consumer industries, such as private companies.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the discussion, debates and intellectual production on race and racism is not new, but it does seem to have more presence in public discussions on the subject. Despite the importance that the issue of race has had in the academic, political and intellectual discussion in the region, it is only since the 2010s that it has become more important in the public debate on the subject.3 when various sectors have taken an interest in the subject, both sectors of civil society and academic and business circles have seen in the neoliberal policies of recognition a new economic niche.

But, in general, how do we understand anti-racism? In the English-speaking world we find a first definition of "alternative grammars of anti-racism",4 understood this as a useful concept to "capture actions and discourses in which racial inequality and racism were not explicit or central, even if not entirely absent, and yet had what we consider to be anti-racist effects in that they challenged the racialized distribution of power and material and symbolic value" (Moreno and Wade, 27: 2022).

Anti-racism has not always been named as such, in that sense it is important to mention a fundamental distinction of the work done in this field. First, for the people who in the sixties of the twentieth century xx struggled globally against the structures of domination based on a widespread biologicist notion of race, but also on the other denominations: by social class and by sexual orientation and gender identities. It is important to make this distinction in order to think that when we talk about anti-racist struggles or anti-racism in general we are not only talking about the struggle of African American people in the United States during the period of civil rights organizing, but also about other forms of supremacy, which for social movements were always connected to the idea of domination.

In the wave of anti-racist policies over the last 20 years we observe that, just as in the struggles for the recognition and expansion of state notions of white mestizo citizenship by black and indigenous organizations throughout the continent, these were co-opted by neoliberal policies, resulting in what Charles Hale (2005) calls the "neoliberal policies" of the United States. neoliberal multiculturalism. In the same sense, the anti-racist organizations that have proliferated in Latin America, as well as the discussions related to this social phenomenon, have also taken a neoliberal turn.

In 1994, for example, in Mexico, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, as well as other indigenous autonomist organizations, such as the crac-pc5 in the south of Mexico, already had a position that we could point out as anti-racist and strategic, by generating community and autonomous organization at the margin of the State and a search for people and social groups allied in the struggles for democratization and access of all citizens to basic rights such as health, security, housing, education, peace, culture and territory, without the above list being exhaustive.

From the above reflections I propose to think of the imperial notion of race as an uncritical and distant form of social movements, a perspective that looks at the constitution of a North American academic body excluding from political, theoretical and academic analysis, the historical experiences and intellectual production that the global south, specifically in Latin America and the Hispanic Caribbean, have been carried out on the broad notion of race. That is, following the idea of the U.S. position as imperial expansion, we can see how even in "critical" discourses the historical experience and intellectual production of radical history in the Latin American and Caribbean region is obliterated.

Following the mobilization for the assassination of George Floyd in May 2020 in the United States, the movement was created. Black Lives Matter and with it a discussion that went beyond the media borders of that country. At least in Mexico, this was the point of reference in the media discourse to account for Mexican-style racism, since the black-Afromexican movement had been working for years for the recognition of this population.

However, one of the central arguments in what I would call neoliberal anti-racism is that it took as its starting point the experiences and contextualizations of race in the historical experience of the United States, leaving aside the historical experience of racialized groups as non-whites on the national territory. After Floyd's assassination, the history of the civil rights struggle in the U.S. has been a historical one. U.S. became the subject of many television series, movies, podcastamong other media products.

The experience of African-American people and populations is marked by the historical ways in which they were included as second-class citizens in the American nation. Based on these discourses linked mainly to skin color, studies have proliferated in the Latin American region that, based on skin color,6 body features, among other marks, have read a form of racism.

On the other hand, there are readings linked to experiences in the Anglo-Saxon world,7 that have a matrix of division between the indigenous and the black as markers of culture/race and, therefore, of readings on racism.

In this sense, the diverse experience of countries such as Mexico, where in addition to the indigenous, the black and the mestizo, we find the "prieto", as those populations that, on the one hand, make exercises of counter-miscegenation and, on the other hand, are not recognized within the idealization of the mestizo, is erased.

I call this decontextualization of the specific historical processes of Latin American and Caribbean territories in relation to the indigenous, black, Afro-descendant and indigenous-descendant inhabitants and their links with the state technology of creation of a mestizo subject, of a mestizo discourse in the territories we now call Latin America and the Caribbean, the imperial idea of race. In this imperial notion of race there is a domination of the public discourse of the history of the United States, a public narration in which the racial is linked to color, to phenotype, but also to the obsession of not contaminating the blood of the indigenous peoples. white nor with a drop of blood from other ethnic or cultural groups.

From sex-generic dissidence, class to the rainbow-washing8 LGBTTIQ+: the black as reinvention

Currently, we observe that many of the anti-racist struggles have left aside a reading linked to the sex-gender orientation and the social class of people, that is, there is a reading of anti-racism as a struggle for the representation of racialized subjects as non-white in the spaces of power, communication, media management, among other logics.

The same thing happened with the movement lgbttiq+ in Mexico, given that the demands of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual de México linked to the discussions on revolutionary social change in the country during the sixties and seventies of the last century, always came with a reading materialistic, in the colloquial Marxist sense.9 The turnaround of the mobilization lgbttiq+ in recent decades has been marked by the politics of consumption and hyper-visibilization of certain homonormative groups within diversity. The idea of sexual dissidences joins the notion of "prietez", to give that twist to anti-racist policies, as Jorge Sanchez Cruz points out:

Nation-states are constructed by the exploitation, dispossession and denial of non-normative people, and Muñoz and Ferguson let us know this. Both provide a kind of decolonization of the field of queer studies and queer theory, forcing them to emphasize the gaze on the survivals of coloniality and slavery, their techniques of forced labor, their territorial excavations, their depletions of the racialized body, and the creation of structures that generate a slow death (Sánchez Cruz, 2025,257).

If we think of these twists and turns of the cuir and the racialized, what is the meaning of the prieto in our days? So it appears in the definition of the Dictionary of Mexican Spanish:

Prieto1 adj. and s. Having dark skin, like that of most Mexicans: "Having a good land, a hard-working husband and a chilpayate. prieto and smiling with eyes wide open as if frightened", "I'm leaving now/ and I'm taking my prietita”.

2 adj. That is very dark in color or black: a private horse, the black hen, pinto beans, sapote prieto.

And in the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language:

Prieto, ta

From tighten.

1. adj. Tight or snug.

Sin.: l tight, tight, snug, tight, narrow.

2. adj. hard or dense.

syn.: l hard, compressed, dense.

3. adj. miserly, meager, greedy.

4. adj. Said of a color: Very dark and almost indistinguishable from black.

5. adj. colored prieto.

6. adj. Cuba. Said of a person: Of black race. U. t. c. s.

7. adj. Said of a person: Of brown skin.

Syn.: l moreno.

Likewise, Tito Mitjans points out that it was Sylvia Wynter who used the term prieto to think about Latin America and the Caribbean:

Sylvia Wynter (2003) presents a genealogy of the term prieto that provides us with a decolonial and anti-racist underpinning of the term at a time when the word is gaining political force in Mexico. The philosopher recovered this term from a report from the beginning of the 20th century. xvii written by the Spanish Capuchin priest Antonio de Teruel, in which he explained that the indigenous people of the Congo considered darker skin colors as an expression of great beauty. Those who were born with lighter tones became darker as they grew up, as a result of their mothers using an ointment or exposing them to the sun to achieve this effect. The priest explained that due to this chromatic value of the skin, so important for the Congolese, the Europeans seemed ugly to them and also demanded that the Spaniards call them prietos, not negros, since for them only slaves were called negros and, therefore, negro and slave meant the same thing (Wynter, 2003: 301-302) (Mitjans, 2023: 188).

Lo prieto has different and contextual readings by countries, as we can read in Wynter's words; I bring up Wynter, read by Mitjans, as an exercise of cultural translation not only from English to Spanish, but in terms of cultural circulations and contextualized readings in Latin America and the Caribbean of authors published in the global North, but who think of the South as episteme. In the Caribbean, the historical distinction of lo prieto is different from how it is read in Mexico. While in countries where statistically the black or afro-descendant population is larger than the indigenous population, the notions of color and, therefore, the forms of naming are broad, in countries like Mexico the word prieto is associated to social class and also to ethnicity, markedly in the color of the skin of the person spoken of or the population group that is not indigenous, is not black and is not white; We could think then that in mestizo identifications, social class is always associated with the possibility of "whitening", as Fabrizio Mejía Madrid points out:

The "prieto" is the mestizo to whose pigmentation is attributed, at the same time, indolence, ignorance, atavistic resentment and sentimentalism. It is the continuation by other means of a war against the poor: the lépero of the Colony (not of his neighborhood, but of the viceregal period) gives way to the "pelado" of the Independent Republic (Mejía, 2018: 22).

The deer is, then, a synchrony between skin color, diffuse identities and social class in a racist environment that reads the racialization associated with different uses of language, space, among other forms of recognition and stigmatization of the other, as Mar Coyol points out in an interview.

From ethnic gaze to political construction: political exercises of self-representation.

Mar Coyol (1994) is originally from Teoloyucan in the State of Mexico, he decided to study art and points out that "in those spaces of learning and teaching in the art world there is a lot of violence, a lot of racism and classism that exists in the world of the arts. Much of my work has to do with this direct questioning of the arts and this is reflected in my work and my projects" (Coyol, "For an anti-racist future", 2024, 57m11s).10 Coyol also talked about how during this time one of the questions he has worked on is how to think about the black, since he identifies himself as a black person, a sex-gender dissident who seeks spaces of creation that have political elements. And it is also a manifestation of the way in which "the exoticization of black bodies is denounced", but also a way in which his art dialogues with the street.

From those experiences in which "between 2016-2017 we made a series of portraits, many of us felt alone and when we got together the internal fire was lit to carry out artistic and cultural projects and take spaces in museums in the public space" (Coyol, "For an anti-racist future", 2024, 1h27m28s); the artist also began to make different reflections in the sense of the importance of commonality from his new project Moyokani, in which he suggests:

...I am interested in interconnecting the systems of oppression of race, class, sex, gender, ethnicity and sexuality and I am very interested in the enunciation, the slogans, the neighborhoods, the rurality, the everyday life, the landscape and the conformation of the political agencies of the characters that I imagine. To give them the possibility of existence to these problems, resistance and survival that have always existed in history (Coyol, "Por un futuro antirracista", 2024, 1h7m23s).

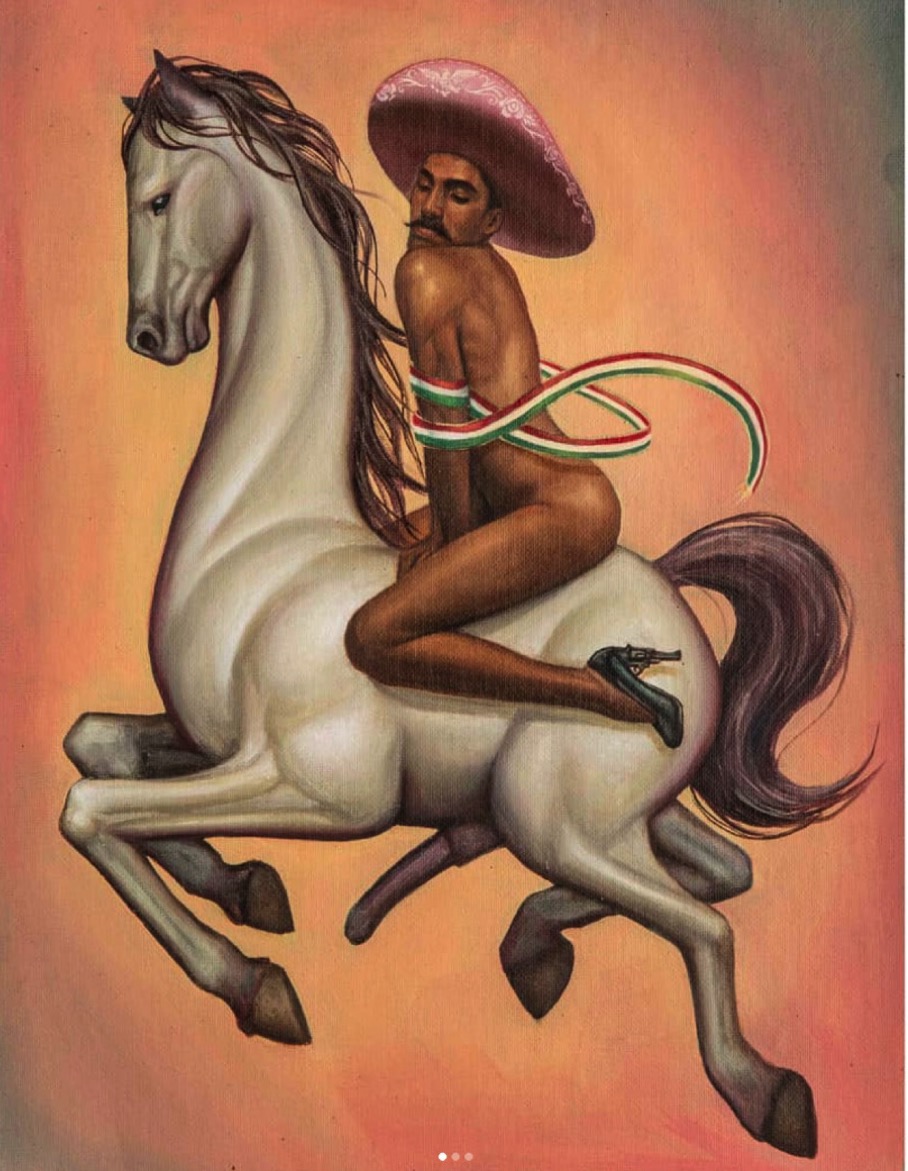

On the other hand, there is the work of Fabián Cháirez (Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, 1987) a person who identifies himself as homosexual, jota and unequivocally prieta, which rubs against the cuir.11 Cháirez's work as well as his presence in the Mexican public art world came on strong between 2019 and 2020, following a series of discussions regarding his work. The revolution (2014), which shows a naked Emiliano Zapata on his horse, wearing high heels and visibly feminized.

Audiodescription: On a light orange background a white horse with a very long neck is held in the air. He has an erect penis and appears to be jumping, his tail is down and so is his head. Above him is a naked, busty man with heels that have a gun at the end of the shoes and a large, round, pink hat. He is wrapped in a ribbon with the colors green, white and red. The young man has a mustache and is in a sensual pose, facing the viewer.

In view of this painting, several discussions were sparked off about the improper of the work in relation to the historical character, who has always had a hegemonic masculine presentation and, in addition, is related to the idea of the nation as a space for the creation of heroes and masculinity; therefore, that a homosexual person represented that role was unforgivable.12

In this sense, we can see that there are racial and gender operations in the idea of the construction of the "prieto", as I pointed out in previous paragraphs, the racial was always a state construction and now it returns through the hand of these artists who vindicate the "prieto", as Fabián Cháirez points out:

I associate the black with what is popular, with what is close. The visible and common, with the closeness of certain activities... I'm going to talk to you with my work: playing soccer, eating a corncob. That which does not have the privilege of the white. Everything that some people call popular within Mexicanity, not only because of the color of the skin, also has to do with socioeconomic and cultural issues (Cháirez, personal communication, July 5, 2024).

On the other hand, for Mar Coyol, the Prieto has a concrete history that does not begin with the activism of the sixties,

[...] but with the way in which history expands and breaks linearity. It is very important to me to say that black people have agency, that we are not alone, we are building community. It is important for me to work on how black, black, indigenous people dismantle racism through poetry, art, academic research (Coyol, "For an anti-racist future", 2024, 59m53s).

In addition to the above, it seems important to point out that the works of both artists represent people from the community. lgbtiiq+ who have historically been underrepresented in art, street art and advertising and who, as Mar Coyol points out, are black, indigenous, black and Afro-Mexican people who are always in social spaces such as public transport, economic kitchens, markets and other spaces in which the idea of race, class and gender identity can be seen to be at play, in what the black-Afromexican photographer Hugo Arellanes has called a worthy representation13 (H. Arellanes, personal communication, January 2025), in relation to the way in which many people racialized as non-white have been represented from reification. To follow this idea, Coyol asserts, in defining the notion of self-representation: "We ourselves, from the tools of art, can give an account of our life experiences, be our own subjects of study" (Coyol, "Por un futuro antirracista", 2024, 1h7m23s).

Mar Coyol also pointed out in the interview that "in the field of art and anti-racist activism was organized in Octubre Prieto, 2021, and started in Argentina. Here with Prietologías hiv and racialization, as an artistic endeavor that puts bodies and tight histories at the center" (Coyol, "For an Anti-Racist Future," 2024, 1h35m27s).

Image, memory and quality

The pictorial image has been the subject of a variety of methodological and analytical approaches. In this paper, I focus on the relationship between materiality, discourse and self-representation, rather than on a technical analysis. In this sense, the idea of a broad aesthetic experience14 is the analytical proposal that guides this document, understanding by aesthetic experience what has already been worked on in relation to the cuir:

We can think of the aesthetic experience, given the interaction between the aesthetic object and the aesthetic perception, as an experience that is not only specular, but also spectacular. Specular in reference to the relationship between the spectator and the work, in a process of projection of expectations that they bring with them and that are also reflected and shared with their communities of appropriation. And this specular relationship can be spectacular, as recognition can be transformed into representations recreated by the spectators. The aesthetic experience thus goes beyond the meanings contained in the narrative, it is sensibly perceived and transformed into manifestation. The appropriations that the self makes when encountering narratives, which generate the production of meanings, are not only a technical exercise of translating words, images and sounds, but are also processes in which the experience of recognition takes place. The production of meaning in the work is present in the poiesis, in the movement enunciated by the author, but it is only completed in the aisthesis, in the spectator's experience, which goes beyond the decoding of what is materialized in the aesthetic object and delves into sensitive perception, which involves the spectator in his or her social place. And this happens as a shared sensibility with communities of appropriation and recognition. As Eliseo Verón (2004) teaches us, the elaboration of meaning involves two grammars, that of production and that of recognition, which takes place in the confrontation between what is produced and what is recognized (Mendes de Barros and Wlian, 2023: 55).

From the previous idea about the aesthetic experience as part of a process of construction of community meaning, it seems relevant to me to analyze the works of the two authors mentioned here; I am interested in thinking about how the processes of self-representation are produced, not only in terms of how the images are seen, for example, in a museum, where we can see people of sexogenic dissidence racialized as non-white, and if it will be possible to carry out processes of decoding in which diversity implies more than the idea of racial and cultural ethnicity.

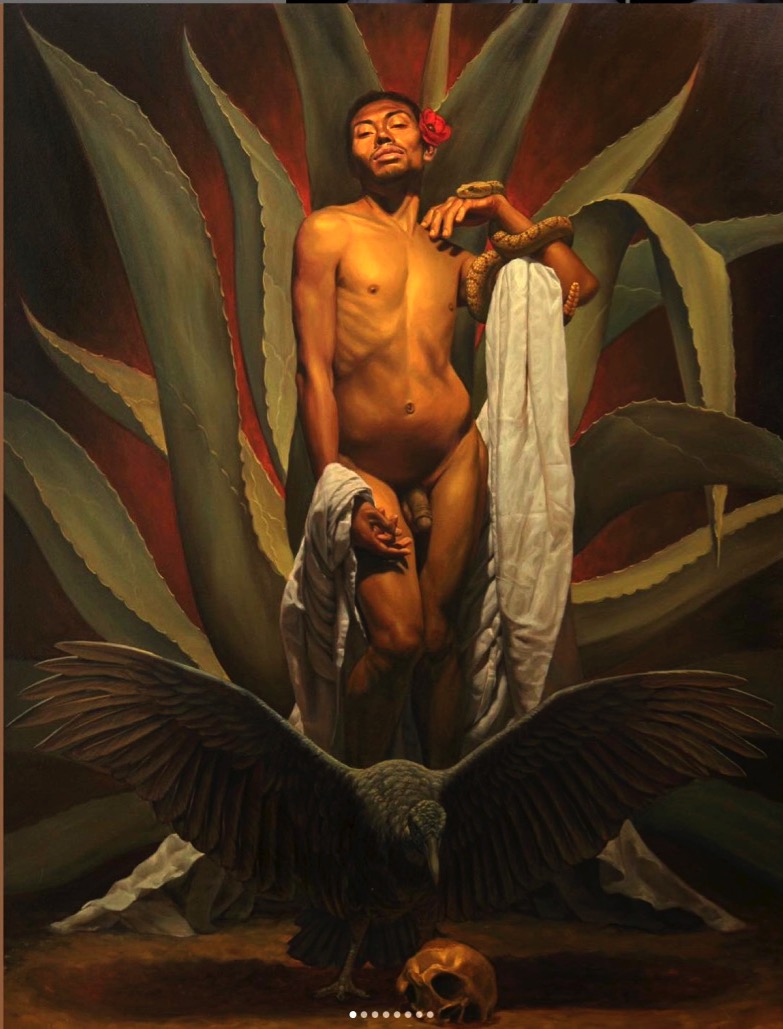

On a terracotta background, an agave of almost two meters, with twelve fleshy, green leaves, with delimited edges on the outside, with other leaves growing from them, unfolds. In the center, a naked man, dark and young, looks at us with his chin raised, with a seductive gesture. On his right ear, he has a large red flower adorning his face with little hair, with little beard. He is a young man of about 25 years, thin, dark. In the center of the image, we see his penis and his knees together. On his right wrist, he has an ochre snake entangled all along his arm; on the deltoid muscle of that same right arm, he has a white sheet rolled up that falls behind him and we see it rolled up again on his left wrist. At the level of his legs, there is a black crow with open wings about to peck at a human skull.

The very idea of self-representation15 I think it is important to think about it here, because it can produce more than images that feed the neoliberal policies of a look that pretends to be decolonized; I am interested in seeing what are the antecedents or histories that make it possible for there to be a discussion about self-representation today.

In the field of cultural studies, there has been profuse writing about the forms of representation of otherness, of those subjects who being on the margins have constructed the senses of the center; as Stuart Hall (2014) and Edward Said (2007) already pointed out, the ways in which the West constituted fantasies about the East gave rise to the understanding about such regions, territories and multiplicity of cultures. What interests me is what happens when there is political, that is, discursive, space for different alterities to break into political and cultural spaces to say something about different issues. In that sense, it seems important to me to think of self-representation also as economic circuits in which racialized people as black, self-defined as indigenous, black, Afro-Mexican or black burst not only in the potentiality of what is seen, but also in the political economy of cultural processes.

To continue with this reflection, a clear example of specific exercises of self-representation is linked to political, cultural and economic projects such as community cinema, a practice in which indigenous women film directors are not only in charge of the script, direction and management of film art, but there is a clear political intention; first, to tell their stories from a non-exoticizing point of view; second, to generate economic and labor spaces for underrepresented people in the artistic and cultural fields, as is the case of indigenous black, Afro-Mexican and migrant populations, lgbttiq+blacks, among other groups. Thirdly, there is a potential in the generation of new people who are trained to carry out specialized work in the fields of art and culture.16

Mar Coyol has a very particular view on this relationship between racism, anti-racism and art:

Museo de Arte Latinomaricón Antiracista (bad) arises with the intention of forcing a dialogue on racism, classism, the system of colonial oppression of sex and gender and decolonial processes in art. The Museum is a tonalcatépetl, which is a Nahuatl word that means the mountain of supports, where the most important thing, which is life, is cared for and preserved. Our line of work, the line of work that I am interested in, mainly supports collective projects or projects with a community scope. lgbt and racialized, works through exhibitions, group shows, artistic residencies, creative laboratories and actions and moments of coexistence; reflecting, dialoguing and complexifying our creative and political practices, some of our projects focus on transfeminisms, cuir culture, seropositivity and anti-racism ("For an anti-racist future", 2024, 1h38m09s).

Prieto as a deviation, prieto as a political space.

The artistic work of the two people presented in this article is eminently a political work. As in countless artistic projects, the relationship between these two spaces is not a novelty, what is an exception to the norm is that these spaces are discursively interconnected both in the image and in the words of the creators.

It seems that we are in front of a political production that drinks from the previous mobilizations linked to ethnicities to give a blow on the table, a soft blow that accompanies the resignification of the word prieto, of the action of squeezing feminism, as black feminisms had pointed out in Brazil (Carneiro, 2017). Likewise, we can observe that artists Mar Coyol and Fabián Cháirez think, act and produce art from a very particular perspective, which is the idea of making community. Likewise, both twist the idea of the depriest from a cuir perspective:

Theorizing queer/cuir in Latin America has also meant discussing non-heteronormative ways of life, modes of affectivity, the politicization and desirability of "other" bodies and non-hegemonic artistic expressions; as well as to analyze multiple routes through which non-white, non-heterosexual, non-cisgender subjects make themselves intelligible in their contexts and deploy a whole series of singular, creative agencies that put in check the prevailing sex-gender, racial, bodily and class normativities, either tensing them or twisting them (Parrini, Guerrero, Pons, 2021: 2).

Mar Coyol points this out clearly when describing his project bad:

bad was born from a very special moment to take up the idea of caring for life, the collective care that is the tonalcatépetl. When it was born badWhen I created it, I stopped thinking about art and I cared more about life. We cared about talking about our experiences, about building a place, a refuge that would house our stories and our memories that have been denied by the systematic invisibilization of black people (Coyol, "For an anti-racist future", 2024, 1h40m39s).

During the last few years, Coyol has gone from thinking about the representation of the masculine to an experience linked to processes of creation in common, with people of sex-generic dissidence.

For Fabián Cháirez, the importance of self-representation is not to make the black people emerge, but rather - as Mar Coyol said - to force them to be seen in a dignified way, to account for a space that is already occupied by black people. One of the effects of racism is precisely the impossibility of reading all bodies with dignity:

When I start to make the more forceful pieces, such as The dreamwhich shows a person lying down with hummingbirds and the mantle of the Virgin [...] I just remembered that it is a reinterpretation of the mantle of the Virgin and Juan Diego. This piece participated in a collective exhibition and when everything was already assembled the owner of the gallery and the curator of the exhibition was looking at the work, when the owner of the gallery was looking at the work with another person he started to make fun of the painting because it was a faggot and there I realized: suddenly I realized the very strong racism (Cháirez, personal communication, July 5, 2024).

In this document, the intention is not to present the prieto as something finished and unproblematic; on the contrary, it is to think about the spaces of discussion and action that self-identify as anti-racist with their peculiarities, as Cháirez says:

Before Bellas Artes I did not have a reference of people who painted racialized people, sex-gender dissidence. I was ashamed to approach my work from the perspective of my own privilege, because I was always questioned if I was sufficiently privileged (Cháirez, personal communication, July 5, 2024).

Tightening contemporary racial discourses

I have gone through several concepts that make it possible to accompany the reading of some of the reflections of Fabián Cháirez and Mar Coyol in relation to the idea of race/racialization, cuir experiences, aesthetic experience and the notion of the deer as a political subjectivation that they are promoting in urban and cuir environments to point out processes of appropriation of spaces in the world of art, culture and politics.

To put the issue of the "prieto" at the center of the debate in certain communities seeks not only to find a space for artistic enunciation, but also to name the violence experienced by the people of the community. lgbttiq+ racialized as non-white in different settings; it also functions to show organizational processes that respond to the cuir de cuir policy of chosen family as a life option beyond the idea of the heteronormative family. They also generate, in the midst of canned identity politics, a deep social bond between people who were historically represented without particularities and stripped of agency even within visual frames.

In this sense, the notion of a dignified representation of the deprive people of the community lgbttiq+ goes from a contemporary construction of their corporealities, the vindication of beauty as a human aesthetic experience and not only the excluding experience of whiteness as beautiful. Also in the different images that we see in this text we observe a wide, diverse, complete and complex corporal posture on the deprive. On the other hand, also the feminized postures of some of the subjects painted by Fabián Cháirez include the possibility that the national history was not made only by heterosexual men and women, but plays with the historical presence of the population. lgbttiq+ in the different moments and historical feats of the Mexican nation.

Likewise, both Coyol and Cháirez expose the black people in the dignified life of the everyday: they enhance their beauty, but always with marks of class, of the popular, by painting the beauty of indigenous, black and black trans women in specific contexts where daily life takes place, for example, in flowerpots made from empty buckets of house paint or in landscapes of the Mexican region linked to muralism.

Likewise, the erotic appears linked to beauty and not to exoticization, which was the constitutive feature of the historical form of representation of racialized people and the community. lgbttiq+.

The images, the body: self-representation

In the images that I brought to this article we see diverse ways of thinking about the racial, the jotería or the cuir and the prieto marked on the body. Such marking is not only in the sense of skin color, but also in that which is seen as deviant and outside the norm of the "beautiful". In the case of Cháirez, both in the painting about Zapata and his horse, as well as in Bixa and the InvocationWe see tight subjects in the darkness of their skin and, above all, we see body shapes and expressions that are detached from heterosexual and in many cases cis-masculinity.

As Olga Sabido Ramos points out:

In general terms, we find a persistent interest in accounting for how the criteria of belonging (whatever they may be) are manifested in the body; for example, in the color of the complexion and face; manners, gestures (e.g., greetings); accent or ways of eating or dressing; and lifestyle in general. On the other hand, some interventions establish how in extreme cases despised identities emerge where the body becomes the main target of stigmatization, rejection and repudiation (due to its "abnormalities", deformities, imperfections or ugliness), insofar as they do not coincide with the hegemonic models of body beauty or with the established patterns of body "normality" (Kogan, 2007; 2009). Equally noteworthy are the presentations in which the body is not only a resource for stigmatization but also for the constitution and resistance of subjectivity (Sabido, 2011: 51).

From the marking of a racialized body as non-white, of a male body without the qualities of heterosexuality, as well as the reworking of historical discourses on which the nation is based, Cháirez's work elaborates a political vision of Mexicanness that fluctuates between realist art and political slogans.

In Coyol's case, the idea of everyday resistance intertwined with sexogender dissidence is present in each of her works. Thus, the conceptualization of the Virgin of Guadalupe is reworked with a black trans woman who is in the same space as the Catholic deity. In the case of the painting Mexico is racistWe can see tight and dissident bodies of gender and heterosexuality, giving the idea of multiplicity in relation to the nation.

The work of the paintings we see in this article is marked by central elements such as thinking about race beyond the ideas of skin color; the idea of sexual dissidence beyond the gay and above all in a relationship of opposition to the Mexican State, specifically in its anthropological, historical and artistic aspects, which had as the center of its productions and debates the politics of miscegenation, based on eugenics.

Audiodescription: in the upper part of the image there is a blue sky with pink clouds, under that sky appear the Virgin's rays of orange color outside and in the center of yellow color; around those rays we read: "I will leave my song in testimonies, and my heart will be reborn and will return, my memory will spread and my name will endure". On the sides of this first image, there are two large buckets of pink paint that serve as vases for two bouquets of astromelias with their long green stems and red flowers. In the center we see a black trans woman dressed in a tight pink mini-skirt and a sleeveless pink navel skirt; she has an earring in her navel and is standing sideways. She is wearing metallic orange heels. From her left shoulder falls a sash that reads "Soy prieta y? The woman has her right hand resting on her waist because she is standing sideways. Her face has a serious but not arrogant expression, she has earrings in her columella and nasal wings; she has long, black, thin braids throughout her hair that fall to the height of her navel. She wears a golden crown, like Miss Universe.

In the works we see there is, in addition to a central discussion of skin color, the body generated and also marked by specific gestures of a sexual orientation other than heterosexual; the use of background colors - in the case of Mar Coyol the Mexican pink and in the case of Cháirez, darker tones - that show us a different but dialogical choice with the monumental murals of the century. xx Mexican and, at the same time, dialogue with Chicano muralism.17 and the street art.

Likewise, we can see the characters in these works in specific spaces of work and leisure: Cháirez's work uses soccer as a central space in his work. BoraIn the case of Mar Coyol, the spaces and geographies are marked by social class, its characters always appear in rural spaces or in urban spaces such as public transportation and economic kitchens, with specific marks of the Mexican.

With Cháirez there are less vibrant colors, although we find the bright yellow that would correspond to Coyol's pink; in both we see with written messages or with messages such as Emiliano Zapata's, a special call of attention of how the Mexican has always been painted and thought from heterosexual masculinity, leaving aside women, feminized subjects, trans, indigenous, Afro-Mexican, black and from underprivileged social classes.

In the case of Cháirez and his controversial painting of Zapata, we have several specific elements linked to the discussion, since he first makes an allegory of Emiliano Zapata, with a young, dark-haired, visibly homosexual man, wearing heels and a pink hat; the horse has an erect phallus, which shows the ways in which gay art has been publicly shown.

In the case of Coyol, in Mexico is racist the text is complemented with "Mexico is colonialist, murderous, classist and cissexist", in the lower pink laces you can read: "Until oppressions are no longer possible the State is not all of us". The petticoat of the trans woman in the center also reads "Prietx sagradx". Thus, the skin colors, the bodies, the clothing and the posters show a Mexico that has not been present in the historical representations of what Mexicanness is. The background of this painting reminds us especially to the work of Dr. Atl, who showed Mexican landscapes without people; in this case Mar Coyol puts in the center a muxe person with men, women and other trans people with clothes associated to the box, the indigenous and the mestizo, always showing with those colors the diversity, another that is never put in the tourist marquees of the country.

At the same time that the artists interviewed in this article contrast themselves with the mestizo-philic policies, the discursive enunciation continues to be in terms of the national, of inclusion and even of the historical, anthropological and artistic re-reading of that which has been denied, crossed out or silenced by the post-revolutionary Mexican State and, above all, by the multicultural public policies in which the gay eclipses the queer, above all, by multicultural public policies in which the gay eclipses the queer, if we understand how some recognition policies also render invisible people who have historically been buried under the logic of race, social class, gender identity and sexual orientation.

On the other hand, Cháirez y Coyol's painting shows racialized bodies that had already been shown in other graphic works, as Cháirez himself points out when giving an account of Mexican muralism in his inspiration. The Chicano art produced by the movement of the same name in the streets of Los Angeles, California, during the 1980s and 1990s, a muralism that will serve to reinterpret Mexico in the light of the migratory phenomena in the neighboring country to the north, appears in some way. In that plastic production, since the late nineties, the racial and gendered issue had been criticized, as Alicia Gaspar pointed out: "Is that that continues to be dominated by a patriarchal cultural nationalism that embraces the symbolic idea of indigenism and restricts its activism to race and class struggles. Gender and sexuality [...] are taboo issues in the Kingdom of Aztlan" (Quoted in McCaughan, 2014: 112).

Likewise, we might suggest with Sueli Carneiro (2017) that the work to blacken feminism in Brazil becomes more present in Mexico as a proposal for tightening feminisms, given that black-Afromexican political processes are on the path to making feminist spaces safe places for feminized black-Afromexican people.

Bibliography

Campos García, Alejandro (2012). “Racialización, racialismo y racismo: un discernimiento necesario”, Revista de la Universidad de La Habana, vol. 273.

Carneiro, Sueli, Aníbal Quijano, Rosa Septien, Rita Laura Segato et al. (2017). “Ennegrecer el feminismo”, en R. C. Septien y K. Bidaseca (eds.). Más allá del decenio de los pueblos afrodescendientes. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv253f4nn.10, pp. 109-116. Buenos Aires: clacso.

Correa Angulo, Carlos (2024). “‘La enunciación antirracista’ en las prácticas artísticas en Colombia: diálogos e in-comprensiones en la investigación colaborativa”, Boletín de Antropología, 39(67), pp. 59-89. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.boan.v39n67a5

Domínguez Ruvalcaba, Héctor (2019). “Introducción: tribulaciones y travesías de lo queer” y “Capítulo 1. Descolonización queer”, en Latinoamérica queer: cuerpo y política queer en América Latina. México: Ariel, pp. 20-43.

Gasparello, Giovanna (2009). “Policía Comunitaria de Guerrero, investigación y autonomía”, Política y Cultura, (32), pp. 61-78. Recuperado en 21 de mayo de 2025, de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-77422009000200004&lng=es&tlng=es

Gleizer, Daniela y Paula Caballero (2015). Nación y alteridad: mestizos, indígenas y extranjeros en el proceso de formación nacional. México: uam, Cuajimalpa, Educación y Cultura.

González Romero, Martín (2021). “Vestidas para marchar. Travestismo, identidad y protesta en los primeros años del Movimiento de Liberación Homosexual en México, 1978-1984”, Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género, El Colegio de México, 7, e582. Epub 13 de septiembre de 2021. https://doi.org/10.24201/reg.v7i1.582

Grossberg, Lawrence (2016). “Los estudios culturales como contextualismo radical, Intervenciones”, Estudios Culturales, 3, pp. 33-44, https://intervencioneseecc.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/n3_art02_grossberg.pdf https://doi.org/10.24201/reg.v7i1.582

Hale, Charles (2005). “Neoliberal Multiculturalism”, PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 28, pp. 10-19. https://doi.org/10.1525/pol.2005.28.1.10

Hall, Stuart (2014). “El espectáculo del ‘otro’”, en Sin garantías. Trayectorias y problemáticas en estudios culturales (2a ed.). Lima: Universidad del Cauca/Envión.

Lewis, Reina (1996). Gendering Orientalism. Race, Feminity and Representation. Londres: Routledge.

McCaughan, Edward (2014). “Queer Subversions in Mexican and Chicana/o Art Activism”, Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 28, 4 (102), 1, pp. 08-117. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43825247

Mejía Madrid, Fabrizio (2018). “No digas que es prieto, di que está mal envuelto. Notas sobre el racismo mexicano”, Revista de la unam, pp. 21-26.

Mendes de Barros, Laan y Luiz Fernando Wlian (2023). “Narrativa cuir, experiencia estética y política en la lucha por la paz: apuntes sobre el cortometraje Negrum3”, Revista de Estudios Sociales, 1(83), pp. 41-60. https://doi.org/10.7440/res83.2023.03

Mills, Charles (1997). The Racial Contract. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt5hh1wj

Mitjans, Tito (2023) “Archivando las memorias prietas disidentes el sur de México”, en Melody Fonseca Santos, Georgina Hernández Rivas y Tito Mitjans Alayón (eds.). (2022). Memoria y feminismos: cuerpos, sentipensares y resistencias. México: clacso/Siglo xxi Editores, pp. 185-216.

Moreno Figueroa, Mónica y Peter Wade (2022). Against Racism: Organizing for Social Change in Latin America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, p. xxvii.

Navarrete Linares, Federico (2022). “Blanquitud vs. blancura, mestizaje y privilegio en México de los siglos xix a xxi, una propuesta de interpretación”, Estudios Sociológicos, El Colegio de México, 40, pp. 119-150.

Omi, Michael y Howard Winant (1994). Racial Formation in the United States. From the 1960s to the 1990s, Nueva York: Routledge.

Ortega-Domínguez, María (2018). “Unveiling the Mestizo Gaze: Visual Citizenship and Mediatised Regimes of Racialised Representation in Contemporary Mexico”. Tesis doctoral. Londres: Loughborough University. https://doi.org/10.26174/thesis.lboro.10294940.v1

Parrini, Rodrigo, Sioban Guerrero Mc Manus y Alba Pons (coords.) (2021). “Introducción”, Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género, El Colegio de México, 7(1), pp. 1-9. https://estudiosdegenero.colmex.mx/index.php/eg/article/view/850

Restrepo, Eduardo (2015). “Diversidad, interculturalidad e identidades”, en María Elena Troncoso. Cultura pública y creativa. Ideas y procesos. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación.

Robinson, Cedric J. (2018). “Capitalismo racial: el carácter no objetivo del desarrollo capitalista”, Tabula Rasa, (28), pp. 23-56. Doi: https://doi.org/10.25058/20112742.n28.2

Sabido Ramos, Olga (2011). “El cuerpo y la afectividad como objetos de estudio en América Latina: intereses temáticos y proceso de institucionalización reciente”, Sociológica, año 26, núm. 74, septiembre-diciembre, 2011, pp. 33-78.

Said, Edward (2007). Orientalismo. Barcelona: DeBolsillo.

Sánchez Cruz, Jorge (2025). “Apuntes para un giro queer decolonial: prácticas y movimientos disidentes en el Oaxaca contemporáneo”, en Estela Serret, Jorge Sánchez Cruz, Fer Vélez Rivera (eds.) (2025). Teoría queer/cuir en México: disidencias, diversidades, diferencias. México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

Schopper, Tiziana, Anna Berbers y Lukas Vogelgsang (2024). “Pride or Rainbow-Washing? Exploring lgbtq+ Advertising from the Vested Stakeholder Perspective”, Journal of Advertising, pp. 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2024.2317147

Telles, Edward E. (2014). Pigmentocracies. Ethnicity, Race and Color in Latin America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Varela Huerta, Itza Amanda. (2023) “Raza/racismo”, en Mario Rufer (ed.) (2022). La colonialidad y sus nombres: conceptos clave. México: clacso/Siglo xxi Editores.

— (2022). “Género, racialización y representación: apuntes para el análisis de productos audiovisuales en el México contemporáneo”, Estudios Sociológicos, El Colegio de México, 40, pp. 211-228. https://doi.org/10.24201/es.2022v40.2320

— (2023). “Batallas por la representación: racismos, género y antirracismos en el México mediático contemporáneo”, Liminar. Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos, 21 (2). https://liminar.cesmeca.mx/index.php/r1/article/view/1010.

Vides Bautista, Uriel (2017). “Arte queer chicano”, Bitácora Arquitectura, (34), pp. 126-129. https://doi.org/10.22201/fa.14058901p.2016.34.581 02

Vivaldi, Ana y Pablo Cossio (Proyecto carla, C. de A. en A. L.) (ed.) (2021). Marrones escriben perspectivas antirracistas desde el sur global. Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de San Martín/Universidad de Manchester.

Itza Amanda Varela Huerta is a research professor in the Department of Education and Communication at the University of California, Berkeley. uam-x. It is part of the snii-Conacyt, level I. Between 2020 and 2023, she was a professor-researcher in the ecg from El Colmex. D. in Social Sciences from the uam-x. He completed a postdoctoral stay at the ciesas-South Pacific. Taught at the uabjo, the ciesasEl Colegio de México, the uacm. He collaborated professionally in The Day and at the Miguel Agustín Pro-Juárez Human Rights Center. Her research focuses on various forms of racism, black-Afromexican political processes, feminisms, cultural studies and postcolonial criticism. Among her most recent publications is the book Tiempo de Diablos: uses of the past and culture in the process of ethnic construction of black-Afromexican peoples. (ciesas, 2023).