Dancing for the saints in the time of covid-19: responses to the 2020 confinement in central Mexico.

- David Robichaux

- Jorge Martínez Galván

- Manuel Moreno Carvallo

- ― see biodata

Dancing for the saints in the time of covid-19: responses to the 2020 confinement in central Mexico.1

Receipt: April 18, 2024

Acceptance: June 26, 2024

Abstract

During religious festivals in the regions of Teotihuacán and Texcoco, northeast of Mexico City, people "dance for the saint," often to fulfill a promise made in a plea for healing or in gratitude for a favor received. Based on fieldwork conducted between 2011 and 2019, and on online interviews and monitoring of Facebook posts in 2020 and early 2021, in this article we explore the impact of the coronavirus on devotional dances performed in the context of religious festivals. In particular, we examine cases of new practices adopted during confinement. Drawing on Jeremy Stolow's (2005) concept of "religions as media," we show how a combination of digital and face-to-face media made it possible for local Catholic communities to maintain the relationship characterized by the principle of do ut des with their patron saint during the pandemic, "albeit in different ways". We conclude by raising several questions regarding the future of devotional dances and religious festivals in these regions, as we enter the second year of restrictions to mitigate the effects of covid-19.

Keywords: coronavirus containment, devotional dances, media, Mexico, folk religion

dancing for the saints during covid-19: responses to the 2020 lockdown in central mexico

During religious celebrations in the regions of Teotihuacán and Texcoco, northeast of Mexico City, people "dance for a saint," often to fulfill a promise made after praying for a cure or to give thanks for a favor granted. Based on fieldwork conducted between 2011 and 2019, online interviews, and the tracking of Facebook publications during 2020 and the first months of 2021, this article explores the impact of the coronavirus on devotional dances done during religious celebrations. In particular, it examines the new practices that surfaced during lockdown. Drawing on Jeremy Stolow's concept of "religion and/as media" (2005), the article demonstrates how during the pandemic, a combination of digital and face-to-face media allowed local Catholic communities to sustain a relationship with their patron saint based on the do ut des principle, "though in a different way." The conclusions pose several questions about the future of devotional dances and religious celebrations in these regions at the start of the second year of covid-19 restrictions.

Keywords: devotional dances, Mexico, popular religion, coronavirus lockdown, media.

Introduction

The abundant use of flowers, music, fireworks and dances in ritual contexts that bring together large numbers of people characterize the religious festivals celebrated in the Texcoco area and the Teotihuacan Valley, regions adjacent to Mexico City. All of this came to an abrupt halt with the containment measures implemented by the Mexican government on March 23, 2020 to combat the spread of the new coronavirus. Non-essential businesses were closed, face-to-face classes were suspended, and extreme restrictions on meetings were implemented, as well as the closure of churches for three months. The dances, when they were performed, were performed on a reduced scale, what some of our informants called "symbolic performances". We understand this term as a way of referring to a reduced scale representation, a substitution of what in normal situations is considered appropriate and what was permitted by the authorities or what was possible, given the health contingency measures and taking into account the perceived danger of contagion during the pandemic. In some cases, the increased use of digital media appears to have led to a proliferation of online postings of photos and videos on a much larger scale than in the recent past, possibly constituting another form of "symbolic representation".

In this article we deal with a form of public religious practice rooted in the peoples of pre-Hispanic origin, on whom a specific type of religious organization was imposed during the process of evangelization in the 20th century. xvi. The complex ceremonial life centered on the community in the old towns -transformed into Indian republics during the viceroyalty- is now self-managed by lay people, so that one can truly speak of a "popular religion" (Carrasco, [1970] 1952, 1976; Giménez Montiel, 1978; Nutini, 1989).2 In using this term we do not mean to suggest that the specific type of popular religion we are examining here is a completely separate phenomenon from the "official Church". In some of its practices a priest is indispensable and only he can say mass. As Kirsten Norget (2021) has pointed out in her study of lay-organized mortuary rituals in Oaxaca, there is a dialectical encounter between official Catholicism and the practices we here call popular religion. We believe that the term is justified by the complex organization controlled by the laity, an organization that is responsible for ensuring that the highly visible community rituals prescribed by local custom are carried out correctly during the annual religious cycle.

In the ritual calendars of the peoples of the two regions considered in this study, the large and frequent expenditures on music, floral arrangements and fireworks on religious festivals, along with masses and the performance of dances, are part of a large-scale offering to the patron saint in a contractual relationship whose object is the guarantee of collective and individual health, prosperity and general welfare.3 Our previous research has found that many villagers participate in or organize dances to fulfill a promise to a saint or to God (Robichaux, Moreno Carvallo and Martínez Galván, 2021). By restricting the celebration of these festivals, the confinement implemented by the arrival of covid-19 abruptly put an abrupt halt to the most outstanding practices of a very public type of religiosity. The usual means of religious expression were thus hindered or prevented altogether, giving rise to alternative solutions on the part of communities and individuals to fulfill in this contractual relationship. Some people spoke of fulfilling their obligations to the saints, "if only in a different way," referring to substituting or reducing the use of the usual means.

In this article, we considered media (in its broadest sense of the term, as it refers to communication), identified masses, music, flowers, fireworks and dances as the main means of communication with the invisible and with the social body in local public popular religious practices. In this approach, we draw on Jeremy Stolow's (2005) concept of "religion as media," which argues that religion can manifest itself only through a process in which techniques and technologies are employed. In his words:

Throughout history, communication with and about "the sacred" has always taken place through written texts, ritual gestures, images and icons, architecture, music, incense, special vestments, relics of saints and other objects of veneration; marks on the flesh, movements of the tongue and other parts of the body. Only through these means is it possible to proclaim one's faith, mark one's affiliation, receive spiritual gifts, or engage in any of the innumerable local languages for making the sacred present to mind and body. In other words, religion always encompasses techniques and technologies that we consider as "media," just as, by the same token, every medium necessarily participates in the realm of the transcendent [...] [authors' translation] (Stolow, 2005: 125).

In the same vein, Birgit Meyer (2015: 336), citing Robert Orsi (2012), has emphasized that, in seeking to make "the invisible visible," religion involves multiple means of "materializing the sacred." This author also understands media "in the broad sense of material transmitters across gaps and boundaries that are central to practices of mediation." To this end Meyer (2015:338) coined the term "sensory forms" (sensational forms), which include bodily techniques that serve as "formats" that "make present what they mediate". Undoubtedly, the dances and other media characteristic of the religious tradition discussed here can be described in this way. Addressing the dances and other media common in our regions and viewed in these terms helps us to understand why people continued to use them and to celebrate festivals, even in reduced form, during the pandemic.

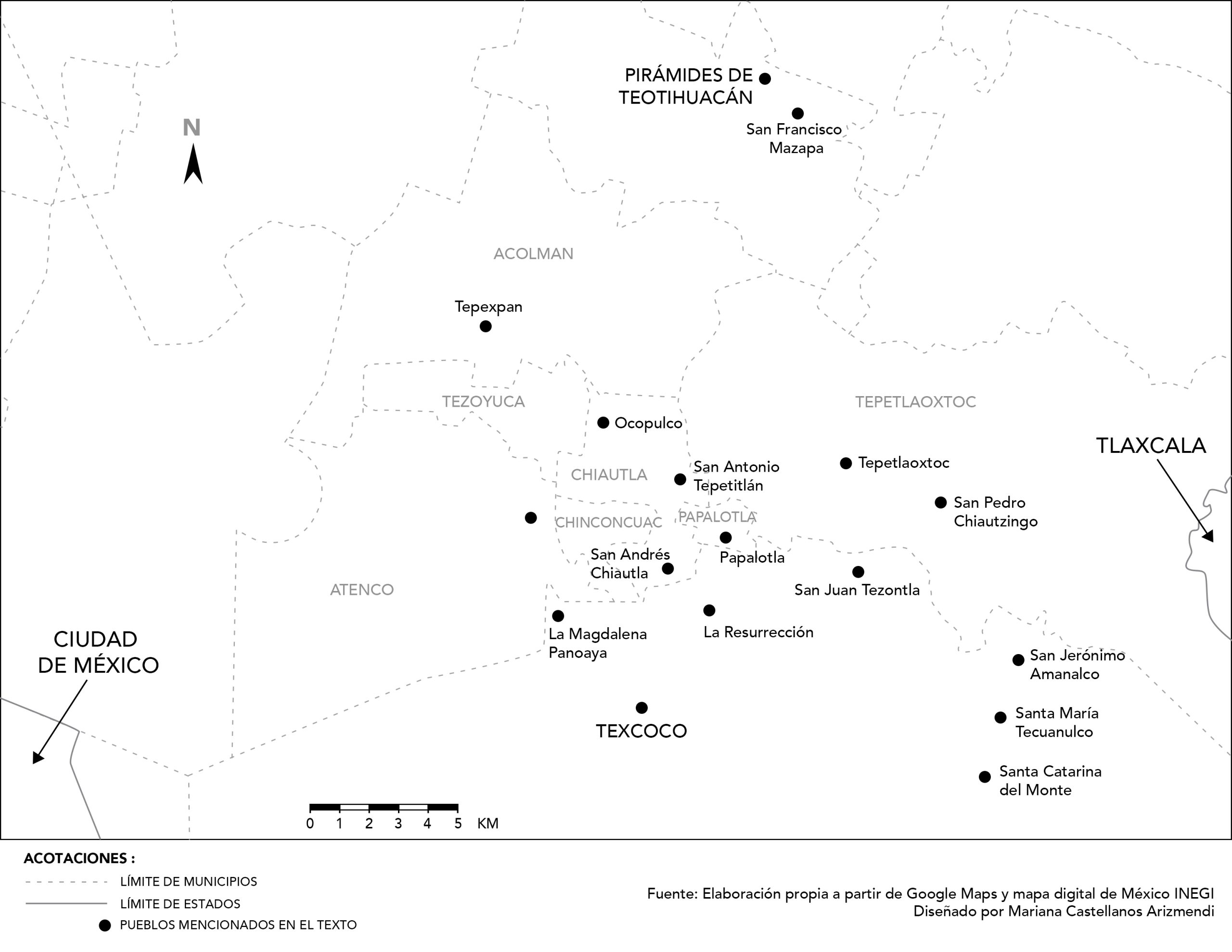

This article is based on three types of sources: 1) a fieldwork characterized by extensive participant observation since late 2011 with an eye on devotional dance groups in more than twenty-five villages in the Texcoco and Teotihuacán regions (see Map); 2) a follow-up of Facebook profiles of municipal governments, parishes, dioceses, local religious authorities (mayordomías), dance groups and individuals in the two regions; and 3) fifty-two interviews conducted primarily on Teams or Meet platforms and, in a few cases, by telephone, between October 6, 2020 and February 18, 2021, with twenty-six informants from fifteen villages. The authors already knew most of the interviewees from the referred fieldwork, but contact was also made with some new research participants through Facebook.

In approaching this research in July 2020, we assumed that the pandemic would soon be over and that we would be able to conduct in-person fieldwork. When it became clear that this was not to be, we took a new direction in our research and turned to a particular version of what has been called "digital" or "virtual" ethnography (see Hine, 2005; Pink et al., 2016). Our strategy consisted of contacting people who had at some point given us their phone number over the years of our fieldwork since 2011. Some were people with whom we had spent many hours during dances and rehearsals and with whom we had spoken frequently, sometimes over several years; others were no more than casual acquaintances with whom we had established little rapport in the field. It turned out that more than half of the telephone numbers were no longer in service. Since in our study regions it is considered improper for women to give their numbers to males outside their family circle, all of our informants were men. Although we managed to make contact with some informants through Facebook, our best interviews were with people with whom we had previously established a relationship in the fieldwork. We also favored interviews with people with computers, as this facilitated eye contact, which enhanced rapport and allowed us to record for later transcription. Given these constraints, all of our informants were men who were heavily involved in the dances in different ways, as organizers, participants or musicians.

It is important to highlight our particular approach to dances and what is known in the literature as the "cargo system," or the community organization of religious festivals. Mexican ethnographers at the beginning of the century xx recognized the religious functions of dances in communities of origin such as the ones discussed here (see Adán, 1910; Noriega Hope [1922], 1979). However, the Mexican State, secular and anticlerical, promoted what it called "regional" or "folkloric" dances, considering them as the expression of the soul of the nation, useful to promote national identity, but which should be "polished" and stripped of their religious symbolism (Gamio, [1935] 1987: 181; Robichaux, 2023).

A similar omission of the religious dimension is also observed in the work on the "cargo system". Early studies considered this institution as a barrier to economic development or as a means to accumulate prestige, and the religious functions and motivations of the participants were scarcely taken into account (Wolf, 1957; Cancian, 1966). Drawing on Danièle Dehouve's (2016: 15-30) critique of this approach in cargo system studies, it is posited that figures other than formal office holders also play a ritual role in ensuring the well-being and prosperity of the community. Among them, in the two regions under study here, are the dance quadrille organizers who, together with the cargueros, form a somewhat acephalous community organization, a local bureaucracy whose purpose is to ensure that the customary rituals of the local annual cycle are properly financed and carried out in accordance with local norms. Although the dances of Mexico undoubtedly lend themselves to analysis from the perspective of performance or performing arts, our interest focuses on their ritual function as part of an offering to the invisible. We share this point of view with our informants, whom we come to understand after years of interaction with them and first-hand knowledge of their experiences.4

This article is divided into three sections followed by final considerations. In the first, we briefly describe the historical background and current functioning of a type of ritual organization centered on the community and controlled by the laity. We then go on to describe the devotional aspects of the dances and their role as an offering to the saint within the framework of a contractual relationship. In the third section we present some of the responses to the confinement measures that affected religious festivals, focusing on the experiences of specific dance crews and individual dancers. These include the use of electronic media; the scaling down of dance performance, what some of our informants referred to as "symbolic representations," and other substitution strategies. In the final considerations we summarize our results and reflect on the future of the festivals and dances, which, in some cases, were suspended for two consecutive years.

How is public popular religion organized in the regions of Texcoco and Teotihuacan?

The terms "popular religion" or "popular Catholicism" in the case of Mesoamerica have been used in different contexts to refer to diverse practices and beliefs that diverge from what has sometimes been called "orthodoxy" or "official" or "organized religion".5 (Vrijhof, 1979; Isambert, 1982; Lanternari and Letendre, 1982). Some authors have proposed discarding the term altogether, considering it "heavily contaminated by pejorative connotations" (McGuire, 2008: 45), and alternative terms such as "lived religion" (lived religion) (McGuire, 2008), "vernacular religion" (vernacular religion) (Flueckiger, 2006) and "local religion" (Christian, 1981: 178-79). "Popular religion", "popular Catholicism" and "Catholicism" (Christian, 1981: 178-79). folk"have been widely used in Mexico since the second half of the 20th century. xx to account for different practices and beliefs outside the "official" ones of the Catholic Church (Carrasco, [1970] 1952; 1976; Giménez Montiel, 1978; Nutini, 1989). We use here "popular religion" or "popular Catholicism" to refer to a specific type of public religiosity based on a lay community organization whose objective is to ensure that the rituals of the annual calendar are carried out according to local community custom.

In the process of contact between pre-Hispanic religion and Catholicism and the transfer of Catholicism to the native populations in Mexico in the 20th century xviIn the smaller villages without a resident priest, the missionary friars trained trusted Indian assistants to enforce compulsory Mass and catechism attendance. In smaller villages without a resident priest, these lay assistants recorded and even performed baptisms or burials and reminded residents of their religious duties (Ricard, 1947: 206-207). The empowerment of lay officials in the early colonial period laid the foundation for what is known as the "cargo system"-also known as the civil-religious hierarchy or mayordomías system-in Mesoamericanist anthropology of the early colonial period. xx (Carrasco, [1970] 1952; Cancian, 1966). Popular Catholicism, as discussed in this article, emerged from this tactic employed by the official Church during evangelization, but today it is a system that has an existence and a logic of its own.

It is important to note that Catholic missionary parishes and their divisions were generally a continuation of pre-Hispanic socio-political and religious units, many of which had a long history of migration of specific groups in which they were under the protection of and identified with a tutelary deity. With Christianization, the deity was replaced by a patron saint, who in some cases had some of the same attributes of the former (López Austin, 1998: 49-50, 69, 76-77). In addition, churches were commonly erected on the sites of pre-Hispanic temples, thus facilitating the transfer of allegiance to the Christian saint. The Aztec gods were thought to provide material means of existence; failure to comply with the ritual would provoke their wrath and loss of their protection would lead to want (Madsen, 1967: 370). The friars endowed pagan songs and dances with Christian motifs and performed them in Catholic ceremonies (Madsen, 1967: 376). In what William Madsen has called a process of "fusion syncretism" (fusional syncretism), "almost all visible vestiges of paganism" were eliminated and Catholicism oriented to Our Lady of Guadalupe became "the central value of Aztec culture in central Mexico" [authors' translation].6 (Madsen, 1967: 378). Patron saints replaced the tutelary gods in each village and received offerings in a manner similar to those of pagan times. Religion remains today "the means of obtaining temporal necessities" and, "as in ancient times, neglect of ritual obligations subjects the individual or the whole community to the vengeance of supernatural beings who punish [...] with disease, crop failures, and other misfortunes"7 (Madsen, 1967: 380-381). As this author points out, on one level Christian saints replaced pagan deities, but the contractual relationship oriented to protection and guaranteeing temporal needs has persisted to the present day.

To emphasize the contractual relationship between the patron saint and the community in Mexico, Hugo Nutini (1989: 88)8 has written:

[At] the end of the century xvii Catholicism had become structured folk which encompassed various elements of the indigenous and Spanish religions inextricably integrated. Superficially, the religion folk had a predominantly Catholic appearance, that is, structurally, the ritual, ceremonial and, in general, its physical manifestations did not differ much from the urban Catholicism of that time.

However, it included (and includes to this day) "the conception of supernatural beings and characters and the do ut des [I give so that you give] that governs the relationship of the individual and the collectivity with its makers". For Nutini, "it is here that the pre-Hispanic contribution is most important and counterbalances the preponderance of the more visibly structured Catholic elements".

"The essentially secular character of the ceremonial organization" in the cycle of public religious festivals in the villages of the Mesoamerican area has been pointed out by Gilberto Giménez. When a priest intervenes, his role is reduced to that of a "ceremonial auxiliary subordinated to the demands of the popular ritual". When diocesan priests replaced the religious orders that introduced the community ceremonial institutions in colonial times, a process of "autonomization" began and, with Independence in 1821 and the separation of Church and State in 1857, the gap between the clergy and popular religion widened even further. The native authorities appropriated the communitarian institutions introduced by the missionaries in the first century. xvi and became "traditional", functioning "in parallel to the Church and, at times, outside the Church and even against it" (Giménez Montiel, 1978: 150-51).

Although much has been written about the cargo system, scholarly attention has focused on a few themes: its function as a leveling mechanism that erased budding wealth differences in supposedly egalitarian communities; its role in reinforcing existing internal differences; the acquisition of prestige by cargo bearers; and individual versus communal funding of religious festivals (Carrasco, [1970] 1952; Wolf, 1957; Cancian, 1966; Chance and Taylor, 1985). Following Arthur Maurice Hocart (1970), we consider the cargo system in our study regions as a bureaucracy or body of officials whose purpose is to organize collective ritual to ensure health and prosperity and ward off illness, misfortune, and death (Dehouve, 2016). We consider the cuadrillas de danzantes as part of this ritual bureaucracy, as they provide an offering to the saint, which is complemented by those of flowers, music, fireworks and masses for which the cargueros are responsible.

The term "mayordomo," recurrent in the literature on the cargo system, is a reference to the fact that these cargo holders were formerly responsible for cultivated plots of land to finance religious festivals (Carrasco, 1961: 493). At present, the mayordomos in the two regions studied are in charge of supervising the organization of religious festivals. They usually hold the position for one year and, depending on the village, are selected in different numbers and organized differently. While in some villages a single group of mayordomos is appointed or elected to be in charge of the entire annual cycle of fiestas, in others there are specific mayordomos for each fiesta. Some villages have a system in which the different positions rotate from house to house and all households end up assuming specific responsibilities in the organization of the annual ritual cycle. While in one village a group of up to one hundred mayordomos is responsible for most of the ritual expenses, in other places every married man or man over eighteen years of age is required to contribute to help the mayordomos cover the expenses. Collectively, the group of mayordomos is known as the mayordomía.

The responsibilities of this ritual bureaucracy include the organization of the customary celebrations of the Catholic liturgical calendar, particularly those related to the birth and death of Christ, and that of the patron saint or other major feasts specific to each town. Major feasts usually take place over a period of nine days, spanning the period between two weekends. During that time, in the church, in its atrium and around it, the work of many months of the mayordomos materializes in its most evident manifestations, coming together in a gigantic collective offering to the saint, consisting of masses, flowers, music, fireworks and dances.

The steward or stewards are responsible for booking the masses and paying the officiating clergy. They are also responsible for having the interior of the church decorated by professional florists with floral arrangements that sometimes cover virtually every wall and even hang from the ceiling (see image 2). They also have to provide special floral decorations, known as coverswhich adorn the façade of the church. In 2018 and 2019, the cost of interior floral decoration ranged from $2,000 to $7,500, depending on the size of the church and how elaborate the floral arrangements were, while the cover cost $1,000 or more. The mayordomo or mayordomos must also hire one and sometimes two wind or other orchestras with between sixteen and twenty-five musicians to play in the church atrium in honor of the saint-sometimes for sixteen hours each day-and to accompany processions and even visits to neighboring villages. In 2019, a wind instrument orchestra of that number of musicians cost about $2,500 to play for five days, with three meals a day, making it a considerable expense, given that many of the villagers we know work in the informal sector.

The mayordomos are also responsible for the fireworks that are used profusely during the celebration. Rockets are fired along the entire length of the procession in which the image of the saint is paraded through the town, an event that can last up to eight hours. Dozens of rockets are fired at the beginning and end of the masses celebrated during the feast, and in long bursts at the moment of the consecration of the host. The feast ends with the lighting of a castle, with one or more towers, a pyrotechnic structure erected in front of the church (see picture 3). Some castles reach thirty-five meters in height and contain explosive charges that often blow up spinning wheels, as well as pyrotechnic representations of the saint, religious motifs or devotional phrases. A large castle with several turrets can cost up to US$7,000.

As we have seen here, public popular religiosity in the two regions studied is a highly organized, community-oriented affair aimed at making the customary offerings to the saints. In the following section we deal specifically with dances, one of the five media which, along with flowers, music, fireworks and masses, are the most prominent manifestations of a contractual relationship with the invisible.

Devotional dances in religious festivals

Dances were an important part of the elaborate rituals in honor of the gods in pre-colonial times and were considered by some missionaries as a form of prayer (Mendieta, 1870: 99). Maceuaone of the Nahuatl equivalents of the Spanish verb "danzar", can also be translated as "to obtain", "to deserve a thing" or "to do penance" (Siméon, 2010: 244). Alfredo López Austin has pointed out that itotiaanother Nahuatl equivalent of the word "danzar", shares a common root with itoathe equivalent of the verb "to speak". This author has proposed that dancing was a way of "talking" with the gods and that a dancer constituted "a bridge", that is, a medium between the people and the deities (López Austin, 2007: 186-87). The reports of the xvi indicate that the missionary friars tolerated the dances as long as they were Christianized. New lyrics were adapted to pre-Hispanic rhythms and songs, and Castilian songs with Christian messages were translated into Nahuatl. The dances were performed in public, in churches, atriums and houses, rather than clandestinely, far from the watchful eyes of the missionaries (Ricard, 1947: 340-41).

In the great majority of the villages in the two regions of this study, it is inconceivable to celebrate the most important festivals without the performance of one or more dances. Together with the numerous masses, flowers, music and fireworks, they are the key elements of a massive collective offering, or don al santo, in the sense of Marcel Mauss (1983). These five elements constitute the means through which the contractual relationship between human beings and the divinity is maintained.9 In interviews and casual conversations conducted during our pre-pandemic fieldwork, terms such as "devotion," "penance," and "sacrifice" often came up in relation to the dances offered to the saints. This is not surprising considering the physical exertion involved in some dances. In addition, the "principals"10 The dancers must pay the musicians, rent sound equipment, tarpaulins and dance platforms, and organize meals, sometimes three a day, attended by hundreds of dancers and their families. They must also spend long hours in rehearsals and, in some cases, learn the dialogues that appear in some dances. A common motive for some men and women to organize or participate in a dance is to fulfill a promise made in a petition for divine intervention in cases of personal illness or illness of family members, as well as to give thanks for a divine favor received. The motivation can also be more diffuse, such as expressing gratitude for enjoying a general state of good health or for having a favorable economic situation. These individual motivations acquire a collective dimension as part of the offering of a community to the saints (Robichaux, Moreno Carvallo and Martínez Galván, 2021: 235).

The devotional character of the dances is clearly manifested in the rituals that take place at the beginning and end of their performance, especially on the first and last days of the festivities.11 The public performance of a dance is always preceded by a group entry into the church where the dancers cross themselves and kneel in prayer before the image of the saint whose feast is being celebrated. In some cases, they sing a chant (a prayer to the saint with references to his purpose) and perform a small part of the dance in the church. This opening ritual may take place after a mass. On the last day of the performance takes place, with great pomp and majesty inside the church, a ritual known as the "coronation". Accompanied by an orchestra that intones solemn and repetitive airs, the dancers enter the church and perform slow, intricately choreographed movements in which each dancer successively embraces each of his companions. This emotional ceremony can last two hours or more and some of those who have been "crowned" or who have fulfilled their promise, that is, their commitment to dance for the saint, give speeches of thanks to the saint or ask for his help to fulfill their promise the following year. It is believed that failure to perform correctly may incur the wrath of the saint and the dancer or a member of his or her family will be punished in the form of illness or accident.

The dances are performed in designated spaces in the atrium of the church or nearby; in some towns as many as five or six cuadrillas of between forty and sixty dancers each may dance for four to six hours with little rest. Although some dances have always had both male and female roles, others have been exclusively for men, boys or girls. In recent decades, female versions of certain dances have appeared in some villages and women have taken on roles traditionally assigned to men. It is common to see fathers dancing with babies and toddlers in their arms and children participating alongside their fathers (see image 4). Some dancers we have talked to, approximately between 30 and 40 years old, say they first danced with their parents when they were four or five years old, and some claim that only when they got older did they understand the religious significance of what they were doing. In most cases they organize their dances with the help of "ensayadores," specialists paid for this purpose; rehearsals begin four to six weeks before the first performance (see note 4). These ritual specialists not only teach the steps, choreography and dialogues of the dances, but also conduct the opening ceremony and coronation.

The types of dances and their variants that we have observed, with or without dialogues, always have a specific theme or plot. But regardless of their content, the opening rituals and the coronation show that they are all dedicated to the saint and that promises and devotion are always present (Robichaux, Moreno Carvallo and Martínez Galván, 2021: 235-38). As we will see in the next section, the confinement implemented by the covid-19 pandemic posed a challenge for the dance squads, most of which were unable to dance. However, some cuadrillas succeeded in their execution, "albeit in a different way," and creative solutions were developed to fulfill the contractual relationship with the saints.

Confinement, social distancing and new ways of fulfilling the contractual relationship in religious festivals and dances.

The declaration of a sanitary emergency by the Mexican federal government on March 23, 2020 meant the immediate cancellation of almost all activities related to the celebration of the festivities in the towns of the Teotihuacán and Texcoco Valley regions. The means, without which the celebration of the religious festivities had been unthinkable until then - mistresses, floral decorations, fireworks, music and dances - were suspended or their use was notably modified. For three months or more after the onset of the pandemic, Masses were celebrated behind closed doors, without parishioners, and broadcast live on Facebook.12 Religious processions took place with the image of the saint parading in the back of pickup trucks with people watching from their homes. The few dances that were organized had a very small number of dancers and lasted much less time than usual.13 Digital media, already used before the pandemic by some dance groups, mayordomos and parishes, gained importance in some towns and became the main means of communication and public religious manifestation.

According to the severity of the restrictive measures in effect on the dates of the fiestas, a variety of strategies were adopted in the different towns. In those towns whose fiestas fell on dates shortly after the imposition of the confinement measures the mayordomos and dancers had little time to adapt. For example, on March 21 the parish of the town of La Resurrección published on Facebook a program of activities for Holy Week and the following week (April 5-19, 2020), the dates on which the patronal feasts of the Lord of the Resurrection are usually celebrated. It included the customary Holy Week processions and masses, plus the participation of five different cuadrillas whose performances were scheduled for two days, as in any other year during the week after Easter Sunday. But on March 28, following the declaration of the health emergency, it was announced that these activities would be modified. In fact, all processions were cancelled and, as the church was closed, masses were celebrated behind closed doors and broadcast live on Facebook. As it was thought that the epidemic would soon be over, it was announced that dances, music, flower arrangements and fireworks would be postponed until Pentecost (May 31 in 2020), the second most important feast of the town.14 This did not happen, as it was soon announced that the Pentecost celebrations would also be cancelled.

The different mayordomías and the different cuadrillas de danzantes de La Resurrección had already made partial payments for various services, including US$12,000 for two castillos and all the rockets. One of the cuadrillas had made an advance payment of US$1,000 for the music and sound equipment. Another had made a $10,000 contract with an expensive group of famous musicians and had already advanced half of the amount before the cancellation. With the cancellation of the Pentecost festivities, the advance payment for the music, flowers and fireworks contracts was "lost". And as if that were not enough, with the new wave of the pandemic recorded in December and early January 2021, which claimed many victims in the town, the 2021 festivities were also cancelled. Faced with this situation, it was decided that the stewards responsible for the 2020 celebration would remain in office in 2021, as they were unable to perform their duties. It was not until 2022 that the festivities of the Lord of the Resurrection were held again, but in a less lavish manner and with a smaller number of cuadrillas than was customary prior to the pandemic.

Over time, some dance groups developed creative solutions to replace traditional practices and endorse the contractual relationship with the saints. One case is that of the Serranos de Tepexpan dancers, who dance in honor of Our Lord of Graces, which is celebrated on May 3. Performed only in this locality and on that occasion, this dance is unique because up to 700 dancers can participate in its execution (see image 5). After a meal attended by up to a thousand people, the dancers go to the church where they enter, with slow and rhythmic steps in two rows of up to 350 people each, singing a melancholic song that opens the dance. After kneeling in prayer and making the sign of the cross, many of the dancers, visibly moved, stare at the image of Our Lord of Graces on the main altar. After this solemn beginning, they leave the church in line, again chanting their song, without turning their backs to the image of Our Lord of Graces. Once in the atrium, they dance for five or six hours, in front of hundreds of spectators.

None of this happened in 2020. As one informant said, the feast was celebrated "as much as possible and with what was allowed, but with a huge dose of faith to receive the blessings of Our Lord." Although there were "few flowers, little music, few fireworks" and no dancers in the church atrium, digital media served to remind villagers of the customary offering of the dancers. In early April 2020, when it became clear that the May festivities would be cancelled, those in charge of the Serranos quadrille opened a Facebook account and called on villagers to share photos and videos from previous years.15 People were also asked to place bows, crowns, hats and other objects used in the dance outside their homes starting at 3:00 p.m. on May 3. Several vans paraded through the town with images of the patron saint and recorded music of the Serranos dance was played while being streamed live on Facebook. Several dancers came out of their homes to watch the procession pass by, some dressed in their dance costumes and, on at least one occasion, a group of children wearing the costumes of the dancers performed some of the steps of the dance.16 Alongside this, there were dancers who used their personal Facebook profiles to post photos of their home altars on which they had placed their dance costumes (see image 6). Symbolically, at the end of the procession, the vans drove away from the church door, backing away in imitation of the movement the Serranos make when leaving the temple, without ever turning their backs to the saint, all accompanied by a recording of the chant sung by the dancers in that ritual act. The people in the back of one of the vans ended the procession with applause and shouts of "Viva el Señor de Gracias" and embraced each other as in the coronation ceremony.17

Over time, as people became accustomed to what Mexican federal authorities called the "new normal," some dance groups managed to celebrate the saints by dancing, but on a much reduced scale. The town of San Francisco Mazapa celebrated Pentecost (May 31, 2020), one of its two main feasts, in full confinement: with no parishioners, the mass was celebrated behind closed doors and broadcast live on Facebook. The images of the saints that are customarily displayed in front of the altar on feast days were placed in the atrium and venerated with floral offerings and a brass band. In normal years, the cuadrillas of the Alchileos and Santiagos, each with thirty or forty participants, perform their dance for five or six hours. On this occasion, a cuadrilla of Alchileos paraded through the streets and a small group of their representatives entered the atrium of the church, made "reverencias."18 and placed a floral offering before the images of the saints, although they did not dance. A group of eighteen Santiagos dancers, accompanied by musicians, entered the atrium of the church and, after crossing themselves and kneeling before the saints, performed their dance for about twenty minutes.19

As cases of covid-19 declined, in early July 2020 health restrictions were relaxed and the mayordomos and principals of the San Francisco Mazapa dances began to organize and raise money for the upcoming fiestas. The churches were now open, but only at thirty percent capacity. For the feast of the town's patron saint, St. Francis of Assisi, on October 4, a very small number of Alchileos danced, beginning with the customary "reverencias" at the house of one of the principals. Afterwards, they paraded through the streets and danced for a while in the atrium of the church.20 These performances or symbolic acts that replaced the normal performances did not release the "principals" from their obligations, since they had to organize the complete dance in 2021.

In San Jerónimo Amanalco, about six cuadrillas usually perform their dances to celebrate the town's patron saint, San Jerónimo, on September 30. In April 2020, despite the rapidly increasing number of deaths in the town during the first wave of the pandemic, the principals of the cuadrilla de los Arrieros decided that, regardless of the circumstances, they would perform the dance, at least on a reduced scale, in the atrium of the church or some other open space. In May, the father of one of them, whose activity had been constant in the cuadrilla, died of covid-19. Because funerals were not allowed at that time, in July, when his ashes were buried, about forty members of the cuadrilla gathered and danced in the cemetery and in the delegacionales offices where the deceased had worked. Although no other dances were performed and other Arrieros dancers and relatives had been affected and had died of covid-19, some members of the cuadrilla were even more determined to dance for the saint so they began rehearsing in August in preparation for the feast. As one of our informants said, "the deceased knew we were going to dance. Let's do it now for them. In honor of their memory, let's continue with this devotion".

The mayordomos allowed them to bring "Las mañanitas" and leave a floral offering for the saint, and only the principals entered the church to pray before his image. Afterwards, about forty dancers, most of them wearing masks, danced for a while outside the church. After leaving the atrium, the members of the cuadrilla also danced outside two small chapels in the village, after which they went to the danzante's house where the rehearsals had taken place and danced there for several hours. The photos and video posted on the Facebook profile of a close friend of one of the dancers elicited a variety of comments. One said: "It was not like other years, but they danced with great faith for our patron saint". But another comment, more cautious, said: "Good for those who had the courage to do this, however, those of us who abstain from some activities join in the grief of the families who have lost a loved one. St. Jerome is in mourning!!!"21

A curious series of circumstances allowed some dancers from Papalotla to dance in honor of the town's patron saint in a very unique way. None of the nine cuadrillas scheduled for the feast of the town's patron saint, santo Toribio de Astorga (April 16), were able to dance in 2020. The town has a deep-rooted tradition of the dance of the Santiagos, which recreates a conflict between Christians and Moors in medieval Spain. In 2017, encouraged by local officials seeking to promote tourism, a group of thirty dancers obtained certification from the International Dance Council (cid), an organization affiliated with UNESCO. This was the subject of controversy, as some less experienced dancers with greater economic resources paid the 164 euro fee, while others with fewer resources could not cover that amount or opted not to become certified because they considered this contrary to the devotional nature of the dance. In October 2020, when the spread of the coronavirus was slowing down, Santiagos dancers were invited to dance in the virtual cultural festival "Quimera", sponsored by state authorities in Metepec, near the state capital, Toluca.

The way the dance was promoted in the festival program as one of the "cultural values of Texcoco" is far from the religious significance it has in Papalotla. However, one of the most experienced dancers and rehearser, who had flatly refused to be certified in 2017, was more than happy to participate, explaining to us that it was an opportunity to dance for santo Toribio. From the beginning, the festival organizers were informed by the dancers that the Santiagos was not a "ballet or folk dance" like other dance groups that appeared on the program, but a religious dance, so a special wooden platform would have to be set up for its performance as is customary in the two study regions. On Sunday morning, October 18, 2020, before traveling to the festival site, a group of twenty-six dancers, accompanied by some family members and fourteen musicians, gathered at the church. Their temperatures were taken, they were required to wear mouth covers, "healthy distance" was maintained, and they were provided with plenty of hand sanitizer. For our informant, the purpose of going to the church was "to honor and ask permission" to santo Toribio "to be able to perform their dance in his honor, permission to perform the dance away from his temple".

From what could be seen in the video posted on Facebook, what took place inside the church was very similar to the initial ceremony prior to the performance of the dance in the context of religious festivities. The ceremony began with the interpretation by the musicians of the Mexican birthday song, "Las mañanitas". The dancers then crossed themselves, knelt in prayer before the image of Saint Toribio, and then proceeded to briefly perform several of the dance steps.22 Once at the festival site, the image of Saint Toribio that the dancers had carried was placed on the wooden platform set up for the performance of the dance. The participation of the cuadrilla, which consisted of a sort of summary of the dance and lasted an hour instead of the usual six or seven, was recorded and later published on the festival's Facebook profile.23 In the opinion of our informant, participation in the festival allowed the dancers to honor, "albeit in a different way," the saint in times of confinement. Although the dancers were required to wear masks, they took them off during the performance. As our informant said, "once we were on the platform, with God's blessing, subject to our religion, our faith, we felt we would be helped. Even though we were very aware of the risk, God is watching over us and nothing bad would happen."

The new wave of the pandemic, which broke out in December 2020 and January 2021, dashed any hope of being able to dance like in normal times in the first quarter of this past year. So-called "symbolic performances" replaced normal dances, and Facebook and other social platforms came to play an important role in this process. During the eleven days of the feast of Saint Sebastian (January 20) in Tepetlaoxtoc, eight dance groups danced in 2020. In early January 2021, the Facebook account "Tepetlaoxtoc Historia, Tradición y Cultura" invited its followers to "virtually celebrate" the festival by posting photos of different events from previous years' festivities.24 One of the mayordomías opened the account "Mayordomía San Sebastián 20 de enero 2021", and posted videos with numerous displays of the usual means - flowers, fireworks, music - as well as symbolic representations of two dances, including one of the Sembradoras. Instead of the sixty or eighty dancers who usually dance, a group of twelve heard mass on the second day of the festival and entered the chapel where they knelt and crossed themselves before dancing for about twenty minutes in front of the façade of the temple. The other took place on the last weekend of the festival and, instead of the usual three or four hundred dancers, thirteen participants in the dance of the Serranos heard mass celebrated in front of the chapel, where they then performed various steps of their dance for about twenty minutes.

During the feast, all the masses were celebrated outdoors in front of the chapel, with little attendance in a space cordoned off to limit access. However, the façade of the small chapel was lavishly adorned with flowers and various musical groups played in honor of Saint Sebastian. Some of the videos posted are of professional quality and appear to have been made specifically for live streaming and viewing on Facebook. One of them attracted more than 8,000 views in just two days after its publication on January 20, 2021. The fireworks show was, in fact, a sophisticated combination of pyrotechnics and laser technology. Geometric shapes and the figure of St. Sebastian with the words "Saint Sebastian, bless us" were projected on the walls of the buildings in the chapel square, accompanied by recorded music. All of this, including the shots taken from a drone, was broadcast live and posted on Facebook.25

In the town of Tepetitlán, symbolic representations of two dances were staged during the festivities of the Virgen de la Candelaria (February 2, 2021). Every year, on the occasion of this feast, the Santiagos quadrille stages a spectacular and costly performance (see image 7). Although in 2020 a new group of people in charge had committed to organize the dance in 2021, in the face of the upturn of the pandemic they made the decision not to dance. In addition, their commitment implies having several sets of expensive costumes, which often get torn and soiled in the vigorous bouts involved in this dance, so it is necessary to have spares on hand to continue the performance. Those in charge must also provide three meals a day for the three days of the dance, in addition to paying the musicians and covering other expenses. Given the drop in their income, due to the disappearance of the market for their fiesta bread that the inhabitants of Tepetitlán sell on Sundays in front of churches and on patron saint festivals, the bad economic situation unleashed by the confinement did not allow for these expenses. However, as the date of the fiesta approached, a group of dancers who had danced in previous years and therefore had the costumes and knew the parlamentos well, decided that it would be an insult to the Virgin if this dance were not performed for her feast. About sixty men, all wearing masks, danced for an hour to the accompaniment of musicians hired by the mayordomos for the general ritual needs of the fiesta and recited some of the dialogues.

The other symbolic performance staged for the Candelaria festival in Tepetitlán, that of the cuadrilla de los Vaqueros, was somewhat different. In 2020, a group of several brothers and their adult children pledged to organize this dance in 2021 in thanksgiving for the recovery from cancer of the daughter of one of the former. Instead of the usual three days of performances, they danced with masks in front of the church for an hour in a space closed to the public. Our informant, one of the brothers, described this act as "a small symbolic advance [payment]." In this way, they were partially fulfilling their promise to the extent permitted by the local authorities, an advance that they hoped to be able to fulfill in full in 2022. This would include rehearsing, paying musicians, and providing three meals a day to hundreds of guests during the three days they dance.

By early 2022, the symbolic representations that characterized the devotion of the saints in 2021 became a thing of the past. As more and more people were vaccinated and developed a natural immunity to successive waves of the virus, the number of covid-19 cases declined. The ritual cycle characterized by the lavish celebrations described in the first section resumed, although not yet with the intensity of pre-pandemic times. The dances were held under rigorous sanitary restrictions, reflecting the so-called "new normal". As of this writing in early 2022, the maintenance of healthy distance and the use of mouth covers, disinfectant gel and even disinfectant sprays were the norm, although these protective measures soon disappeared in the two regions of this study (see image 8).

Final thoughts

Informed by Jeremy Stolow's (2005) proposal of "religion as media," we have identified masses, copious public displays of flowers, fireworks, and music, along with dances, as the five main media characterizing religious festivals in the Texcoco and Teotihuacán regions of central Mexico. Although the use of all these media continued on a much reduced scale because of measures taken to curb the spread of covid-19, dances were the most affected. Most cuadrillas simply did not dance, although we heard of scattered cases of encargados presenting a floral offering to the saint. In general, there were few cases of "symbolic representations," a term we have adopted from one of our informants to refer to reduced or modified forms of dance. These cases remind us of others of substitution or reduction of offerings in contractual relations with the divinity. For example, according to E.E. Evans-Pritchard, among the Nuer of southern Sudan a cucumber could substitute for an ox or be offered with the promise of a future sacrifice of an animal (Evans-Pritchard, 1956: 128, 148, 197, 205, 279). In a geographical space much closer to our research, Danièle Dehouve (2009:140-41) found that, among the Tlapanecs of the Mexican state of Guerrero, in case of need, an egg or a chick could substitute for a chicken in some sacrifices. The Tlapanecs even bargain and inform the power to whom the sacrifice is made, that they will receive an egg instead of a goat, while presenting excuses explaining that they could not provide the customary offering (Dehouve, 2009: 38).26

With the probable cancellation of the dance in which he was to participate, one of our interviewees expressed an idea that echoes these customs. He said that on the day of the feast he imagined going to church dressed in his dance costume, kneeling and crossing himself before the image of the saint and saying: "You know what, patron? I already came. You know how things are. I'm leaving. Other informants imagined a near future with the performance of the dance during confinement in terms similar to the symbolic representations we have described in the previous section. One of them said that the combat dance in which he participates would have to be performed with a much smaller number of dancers, who would wear gloves and simulate battle, always maintaining a "healthy distance." Another informant noted that some members of his cuadrilla were considering performing an hour-long performance with twenty-five dancers wearing masks instead of the three or four hundred who usually dance, one day instead of two, with recorded music and lots of hand sanitizer. He was aware of the possible risk of being fined by the civil authorities, but said he would gladly pay it: "If there is a fine or something, I'll pay it. In the end I owe more to the employer." He also pointed out that the opening song of the dance says: "Ya venimos, padre mío, a cumplir nuestra promesa" and that most of the dancers had made a promise to dance, whatever the circumstances.

The words of another experienced dancer and rehearser reveal the importance of the religious significance of the dances for many people in the two regions. They also reveal the deep principles underlying observable behavior that has often been considered folklore in Mexico, where "folkloric dances" have been promoted by the state as one of the performing arts and part of the national identity. This dancer imagined a version of dance in times of confinement, stripped of what is normally considered essential. The customary visits and performances by the dancers at key points in town, along with the meals offered by those in charge to the dancers and local people, would be abolished. Instead, only food would be offered to the musicians, since, by custom, it is part of their payment. The dance would take place inside the church, after the mass, once everyone had left. He stressed that the spirit of the dance, its true purpose, is to dance for the saint. The omission of these customary adjacent practices, all performed at "normal times," would "not be a problem" for him.

The similarities between the real and imagined symbolic representations reveal that "the spirit of the dance, its true purpose"-or "the essence of the dance," as another informant put it-is, in fact, an offering to the saint. They also show that these substitutions are intended to maintain a continuing relationship with the saint in times of severe restrictions. But the use of the live streaming and the Facebook post reveal another important religious need that we believe many people in the two regions surely felt during confinement. Insisting on an understanding of religion as "mediation," an attempt to "bridge the here and now and something 'beyond,'" Birgit Meyer (2015: 336), inspired by Robert Orsi (2012), has emphasized that various means are brought together in order to "make the invisible visible." In this tenor, this author has coined the term "sensory forms" (sensational forms) to account for "bodily techniques, as well as the sensitivities and emotions embodied in the habitus" (Meyer, 2015: 338). The dance is a sensory form and, as a public act, serves to make visible to spectators and villagers in general the contractual relationship with the saint. It is in this sense that we believe that the live streaming of symbolic performances, as well as the posting of images of the garments and accessories used in the dances, in addition to videos and photos of dances from previous years on Facebook, constitute an attempt by those who have access to this technology to convey at least part of the sensory dimensions involved in the performance of the dances in normal times. In this way they remind viewers of the currency of the contractual relationship that will one day be visible again through traditional media.

It is still too early to weigh the full impact that the covid-19 pandemic will have on religious dances and festivals. The examples we have provided on the limited use of the usual means, substitution practices, symbolic representations and recourse to digital media give only a partial picture of a truly catastrophic situation that has disrupted the usual sociability revolving around a sumptuous public religiosity. Due to the complexity of human emotions, the inner feelings of the actors are not easy to penetrate, which makes the full breadth of the religious dimension of the dances difficult to capture and express, even under normal circumstances. Moreover, due to the pandemic, our research was mainly limited to people with telephone and, above all, internet access that we knew before the confinement and to villages where surrogate practices were posted on Facebook. Despite these limitations, we believe we have identified several crucial questions that merit further study: did the illness and recovery from covid-19 constitute common motives for making a promise to dance as it was for one of our informants? Did the symbolic performances, in addition to maintaining the relationship with the saint, assume the added function of a plea to end the pandemic? Did the pandemic shake people's faith, paving the way for a possible repudiation of traditional practices due to the perceived abandonment of the saint? Or, on the contrary, will it lead to a reinforcement of the dance offering as a means of averting future catastrophes? Further research is needed even to answer these questions and gain a better picture of how popular Catholicism in Mexico has been affected by the covid-19 pandemic.27

Addendum. Videos and socio-digital media in the ethnographic study of patron saint festivals: their use in the context of the pandemic.28

Since we began our project on devotional dances in 2011 in more than 20 villages in the regions of Texcoco and the Teotihuacán Valley, we dedicated ourselves to videotaping the participation of different dance groups in the framework of the patron saint festivities. In this context, we established a relationship of retribution with our interlocutors -dance leaders, active and retired dancers and their families- by returning in the format DVD a copy of their participation. At first some people asked us: "Didn't you record a little more?" or commented: "It's missing", referring to the fact that some moments of the dance that were important to them were not recorded. This situation showed us that our view as ethnographers was far from our informants' interest in having material documenting their full participation in the dances. It is important to recognize that, in terms of recording and editing, it is impossible to record everything, so our way of collecting had to be modified to incorporate elements that went beyond the dance: processions, banquets offered to the community, masses, visits by the cuadrillas to neighbors' and relatives' houses, as well as visits to churches in neighboring towns.

During the early years of our research we understood that those who participate in the dances also wanted to show their festivities and dances to a wider audience, as they made comments about uploading the materials to platforms such as YouTube. We had been reluctant to release the video recordings out of respect for the individuals; we have only done so on rare occasions when there have been specific requests to do so. The first time was in 2016 when the people in charge of the Chareos crew in Ocopulco, municipality of Chiautla, asked us to "upload the video of the dance to YouTube."29 in order to give more villagers the opportunity to see the dance. In 2017, the new people in charge of this dance asked us again to upload that year's video to the same platform.30 On the other hand, although some of our interlocutors from other villages expressed interest in uploading videos of their dances to the YouTube platform, nothing materialized. We felt that the managers or principals should be the ones to decide on the use of the video material we have accumulated and how it should be distributed. In the meantime, we continue to deliver videos in the following format DVD to some dancers.

Following the contingency measures imposed by covid-19 at the end of March 2020, we had to change our research strategy. Thanks to some contacts we had on Facebook, we realized that this sociodigital network was beginning to gain importance for sharing news about the pandemic and the cancellation of religious festivities among some inhabitants of the towns in the regions of Texcoco and the Teotihuacán Valley. Although some dancers, mayordomos and local civil authorities were already using socio-digital media, we noted an enormous increase in their use. Thus, we began to follow several individual profiles of mayordomías, dance groups and churches with the objective of documenting the measures and decisions taken by those in charge of the dance groups for their public execution when churches were closed and festivities were cancelled.

The constant publication of communiqués by religious and civil authorities opened an important panorama for us to understand the commitment of the inhabitants of the villages to fulfill the saints. This process led us to plan a project with two ways of collection and ethnographic analysis: 1) remote31 and 2) digital. For the first type we contacted our interlocutors and initiated interviews through different platforms (Meet, Teams, WhatsApp, Facebook) and by telephone. In the second type we participated in live broadcasts and recorded text and video publications of the transformation process of the festivities that took place in different towns through Facebook.

During the first months of the pandemic we dedicated ourselves to record, by means of screen captures, the publications of inhabitants and dance groups and mayordomías of different towns, thinking that very soon we would be able to return to do field work. However, due to the behavior of the pandemic and the confinement measures, we found ourselves in the need to resume contact with our interlocutors and have conversations about the impact of the pandemic and the strategies they adopted to fulfill their commitments to the saints. In this process we found the emergence of new devotional practices on Facebook that, in some cases, would replace or replicate pre-pandemic practices.

The approach to the socio-digital network Facebook, as well as the talks through other platforms, allowed us to realize that there are elements that are fundamental for the realization of the festivities, such as dance. Since dance, as a collective act, is one of the practices with great relevance for the patron saint festivities, it was of great importance for us to be able to record how it was going to be carried out. In this sense, our research was subjected to what we could record on Facebook and to the stories that our interlocutors shared with us through the interviews.

A concrete example of this new direction of our research was the close collaboration we had with the people in charge of the dance of the Serranos de Tepexpan for the festivity of Nuestro Señor de Gracias in May 2020. We initiated with them a collaborative process of co-editing videotaped materials that we had produced since 2015 and that were posted on Facebook.32 By May 2021, in a context of reduction of the festival in terms of the number of days of dance performance and participants in the dance and processions in the public space, one of the authors, Jorge Martínez, did face-to-face fieldwork in Tepexpan. At the same time, we continued to consult the Facebook profiles since the activities of the festivity took place in a hybrid interaction. offline/on-lineThe image of the Virgin, that is, in the physical space of the town and in the social-digital network Facebook through live broadcasts and a series of publications. On those dates, the measures of social distancing and restrictions for the realization of massive events were still in place, so the festivity, which lasts almost a month, considering novenaries and visits of the image to homes, was compressed to fourteen days, while the dances were performed only one day instead of the usual five.

As part of our collaboration with the Serranos de Tepexpan dance leaders during the 2021 festival, we also co-edited three videos that, at the request of the leaders, were uploaded to YouTube and two were shared on their Facebook profile.33 Undoubtedly, this type of collaboration and retribution as in the case of the Chareos de Ocopulco has allowed the videotaped material to reach more people in the villages and beyond. But an even more important aspect is that, since the covid-19 pandemic, the people of the villages in our study regions are increasingly familiar with the use of socio-digital platforms and see them as a means to live the festivities and fulfill their commitment to their patron saints.

*****

Our thanks to the following people who, in interviews on different platforms and by telephone, shared with us their knowledge and feelings about the dances during the confinement:

Joel Aguilar, Alfredo Ambriz, José Báez †, Danae Capistrán Cortés, Arturo Cerón, Eladio Cerón, Miguel Cerón, Antonio Delgadillo, Feliciano Espejel, Eric Samuel Frutero, Samuel García, Juan González, Luis Miguel González, Héctor Hernández, Arturo Herrera (Tecuanulco), Arturo Herrera (Chiautla), Andrés Jaime, Eduardo Morales, Roberto Oliva, Héctor Ramos, Rigoberto Ramos, Benjamín Rodríguez, Alejandro Velázquez, Luis Velázquez, Alfonso Zavala.

We also thank Berenice Delgadillo for providing information to Jorge Martinez outside the context of the interviews, as well as dozens of people from the two study regions who, prior to the confinement, since 2011, welcomed us and shared their devotional practices with us.

Bibliography

Adán, Elfego (1910). “Las danzas de Coatetelco”, Anales del Museo Nacional, vol. 14, núm. 2, pp. 133-194.

Bonfil Batalla, Guillermo (1987). México profundo. Una civilización negada. México: Sep/ciesas.

Cancian, Frank (1966). Economy and Prestige in a Maya Community. The Religious Cargo System in Zinacantan. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Carrasco, Pedro (1970 [1952]). Tarascan Folk Religion: An Analysis of Economic, Social and Religious Interactions. Nueva Orleáns: Tulane University/Middle American Research Institute.

— (1961). “The Civil-Religious Hierarchy in Mesoamerican Communities: Pre-Hispanic Background and Colonial Development”, American Anthropologist, vol. 63, núm. 3, pp. 483-497.

— (1976). El catolicismo popular de los tarascos. México: SepSetentas.

Chance, John K. y William B. Taylor (1985). “Cofradias and Cargos: An Historical Perspective on the Mesoamerican Civil-religious Hierarchy”, American Ethnologist, vol. 12, núm. 1, pp. 1-26.

Christian, William C. (1981). Local Religion in Sixteenth-Century Spain. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dehouve, Danièle (2009). La ofrenda sacrificial entre los tlapanecos de Guerrero. México: Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos. http://books.openedition.org/cemca/873.

— (2016). La realeza sagrada en México (siglos xvi-xxi) México: Secretaría de Cultura/Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia/El Colegio de Michoacán.

Evans-Pritchard, Edward Evan (1956). Nuer religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Flueckiger, Joyce Burkhalter (2006). In Amma’s Healing Room: Gender and Vernacular Islam in South India. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Gamio, Manuel (1987[1935]). “El nacionalismo y las danzas regionales”, en Manuel Gamio. Hacia un México nuevo. Problemas sociales. México: Instituto Nacional Indigenista, pp. 179-181.

Giménez Montiel, Gilberto (1978). Cultura popular y religión en el Anáhuac. México: Centro de Estudios Ecuménicos.

Hamayon, Roberte (2015). “Du concombre au clic. À propos de quelques variations virtuelles sur le principe de substitution”. En ethnographiques.org 30. https://www.ethnographiques. org/2015/Hamayon.

Hine, Christine (ed.) (2005). Virtual Methods. Issues in Social Research on the Internet. Oxford/Nueva York: Berg.

Hocart, Arthur Maurice (1970). Kings and Councilors. An Essay in the Comparative Anatomy of Human Society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Isambert, François-André (1982). Le sens du sacré. Fête et religion populaire. París: Éditions de Minuit.

Lanternari, Vittorio y Marie-Louise Letendre (1982). “La religion populaire. Prospective historique et anthropologique”, Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religions, vol. 53, núm. 1, pp. 121-143.

López Austin, Alfredo (1998). Hombre-dios. Religión y política en el mundo náhuatl. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

— (2007). “Ofrenda y comunicación en la tradición religiosa mesoamericana”, en Xavier Noguez y Alfredo López Austin. De hombres y dioses. México: El Colegio Mexiquense/El Colegio de Michoacán, pp. 177-192.

Lorea, Carola E.; Neena Mahadev, Natalie Lang y Ningning Chen (2022). “Religion and the covid-19 Pandemic: Mediating Presence and Distance”, Religion, 52, 2, pp. 177-198. doi: 10.1080/ 0048721X.2022.2061701

Madsen, William (1967). “Religious Syncretism”, en Robert Wauchope y Manning Nash. Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 6, Social Anthropology. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 369-391.

Martínez Galván, Jorge (2023). “‘Cumplir, aunque sea de manera diferente’: expresiones de la devoción en la ‘celebración digital’ del Señor de Gracias en Tepexpan, Estado de México”, Revista Trace, núm. 83, pp. 113-136. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/trace/n83/2007-2392-trace-83-113.pdf

Mauss, Marcel (1983). “Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques”, en Claude Lévi-Strauss. Sociologie et Anthropologie. París: puf, pp. 145-279.

McGuire, Meredith B. (2008). Lived Religion. Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Nueva York: Oxford University Press.

Mendieta, Fray Gerónimo de (1870). Historia eclesiástica indiana. México: Antigua Librería Portal de Agustinos.

Meyer, Birgit (2015). “Picturing the Invisible. Visual Culture and the Study of Religion”, Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 27, pp. 333-360.

Norget, Kristin (2021). “Popular-Indigenous Catholicism in Southern Mexico”, Religions, vol. 12, núm. 7: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070531.

Noriega Hope, Carlos (1979 [1922]). “Apuntes etnográficos”, en Manuel Gamio. La población del Valle de Teotihuacán, vol. 4. México: Instituto Nacional Indigenista, pp. 297-281.

Nutini, Hugo G. (1989). “Sincretismo y aculturación en la mentalidad mágico-religiosa popular mexicana”, L’Uomo, vol. 11, pp. 85-123.

Orsi, Robert (2012). “Making God’s Presence Real through Catholic Boys and Girls”, en Gordon Lynch, Jolyon Mitchell y Anna Strhan. Religion, Media and Culture: A Reader. Londres: Routledge, pp. 147-158.

Pink, Sarah, Heather Horst, John Postill, Larissa Hjorth, Tania Lewis y Jo Tacchi (2016). Digital Ethnography. Principles and Practice. Los Ángeles/Londres: Sage.

Ricard, Robert (1947). La conquista espiritual de México. México: Jus.

Robichaux, David (2007). “Identidades indefinidas: entre ‘indio’ y ‘mestizo’ en México y América Latina.” Cahiers Amérique Latine Histoire & Mémoire alhim 13. https://doi.or g/10.4000/alhim.1753.

— (2023). “Las danzas en los primeros pasos de la antropología”, Revista Trace, núm. 83, pp. 53-80. 2007-2392-trace-83-53.pdf (scielo.org.mx)

— (2024). “La comunidad ‘corporada’ cerrada en el México pos-indígena: desindianización y el destino de las exrepúblicas de indios en el siglo xxi”, Revista runa, vol. 45, núm. 1. doi: https://doi.org/10.34096/runa.v45i1.14262

— y José Manuel Moreno Carvallo (2019). “El Divino Rostro y la danza de Santiagos en el Acolhuacan Septentrional: ¿ixiptla en el siglo xxi?”, Revista Trace, núm. 76 (julio), pp. 21-47. 2007-2392-trace-76-21.pdf (scielo.org.mx)

—, Danièle Dehouve y Juan González Morales (2023). “Un nuevo texto náhuatl de la danza de los Santiagos: tras los pasos de Fernando Horcasitas en el Acolhuacan Septentrional y el Valle de Teotihuacán”, Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, vol. 66 (junio), pp. 171-250. https://nahuatl.historicas.unam.mx/index.php/ecn/article/view/78144

—, José Manuel Moreno Carvallo y Jorge Antonio Martínez Galván (2021). “Las danzas como ‘exvotos corporales’: promesas individuales y sus dimensiones colectivas en las regiones de Texcoco y Teotihuacán”, en Caroline Perrée (ed.). L’exvoto ou les métamorphoses du don/El exvoto o las metamorfosis del don, pp. 221-53. México: cemca. https://tienda.cemca.org.mx/producto/el-exvoto-o-las-metamorfosis del-don 9782111627147/.

Siméon, Rémi (2010). Diccionario de la lengua náhuatl o mexicana. México: Siglo xxi.

Stolow, Jeremy (2005). “Religion and/as Media”, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 22, núm. 4, pp.119-145.

Vrijhof, Pieter H. (1979). “Official and Popular Religion in 20th-Century Western Religion”, en Pieter H. Vrijhof y Jacques Waardenburg. Official and Popular Religion: Analysis of a Theme for Religious Studies. La Haya: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 217-243.

Wolf, Eric R. (1957). “Closed Corporate Peasant Communities in Mesoamerica and Java”, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, vol. 13, núm. 1, pp. 1-18.

— (1958). “The Virgin of Guadalupe: A Mexican National Symbol”, The Journal of American Folklore, 71 (279): pp. 34-39.

David Robichaux was born in Louisiana and has lived in Mexico since 1966. Trained as a historian in the United States, he holds a master's degree in Social Anthropology from the Universidad Iberoamericana. He holds a Diplôme en Études Approfondies (dea) in Sociology from l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales de Paris, and holds a PhD in Ethnology from the Université de Paris-Nanterre (Paris, France). x). Between 1977 and 2005 he was a full time professor-researcher of the Postgraduate Program in Anthropology at the Universidad Iberoamericana Ciudad de México, where he is currently an honorary professor-researcher. He is a member of the National System of Researchers since 1996 and emeritus researcher since 2023. His research and publications in Mexico and abroad have dealt with family, kinship, socio-ethnic categories, demography, historical demography based on field and archival research in southwestern Tlaxcala and the Texcocan region and on devotional dances in the latter region. He has coordinated six collective volumes on family and kinship. Among his most recent publications areKinship and reciprocity in Latin America: cultural logics and practices, Cuaderno de Trabajo 4.edited with Javier O. Serrano and Juan Pablo Ferreiro. Asociación Latinoamericana de Antropología, 2024; "La comunidad corporada cerrada en el México pos-indígena. Desindianización y el destino de las exrepúblicas de indios en el siglo xxi"Runa, archive for the human sciencesvol. 45 (1): 19-40, 2024; and "Las danzas en los primeros pasos de la antropología sociocultural mexicana: miradas y marcos de análisis", trace 83: 53-80, 2023. https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5791-9903

Jorge Martínez Galván holds a PhD in Social Anthropology from the Universidad Iberoamericana Ciudad de México. She has master's and bachelor's degrees in the same discipline from the Universidad Iberoamericana Ciudad de México and the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Iztapalapa, respectively. Her research topics focus on ethnicity and kinship relations in the Holy Week dance groups in a village of the High Sierra Tarahumara in the state of Chihuahua. In the last eleven years she has dedicated her research to the dances and devotional practices, as well as their transformation during and after the pandemic of covid-19, in different villages of the Teotihuacan and Texcoco valley regions, in the eastern part of the State of Mexico. He has published several book chapters and articles on these topics in national and international journals. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5458-0715

Manuel Moreno Carvallo holds a degree in Sociology from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco (uam-x), Master in Social Anthropology from the Universidad Iberoamericana Ciudad de México and PhD in Ethnology from the Université Paris-Nanterre. Since 2011 he has worked on the devotional aspect of dances and their social organization in the region of Texcoco and the valley of Teotihuacan. She has also worked on the impact of the pandemic on the religious festivities of the people of the eastern part of the State of Mexico. She has worked in the field of visual anthropology, which have been presented in national and international forums. She is currently a member of the lesc-erea (Laboratoire d'Ethnologie et de Sociologie Comparative-Centre Enseignement et Recherche en Ethnologie Amérindienne) and lecturer at the Department of Social and Political Sciences of the Universidad Iberoamericana and at the Center for Anthropological Studies of the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, unam. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9412-2081