Resist dehumanization. Civil society in the face of disappearances, coercion of freedom of expression and forced displacement in Mexico

- Severine durin

- ― see biodata

Resist dehumanization. Civil society in the face of disappearances, coercion of freedom of expression and forced displacement in Mexico

Received: December 12, 2018

Acceptance: December 20, 2018

Parents looking for traces of their children in vacant lots. Journalists who have nightmares in which they are executed by high-powered weapons. Young people who testify to obtain recognition of forced disappearances in Mexico before international actors. Human rights activists who keep track and record of the invisible victims of the so-called war on drug trafficking, that is, displaced people. These themes make up the four texts in this dossier, which were written by women who move between academia and activism. In them the dehumanization of discourse and militaristic actions are exposed, the meanings of those who suffer and resist such circumstances are illuminated, and the cruel way in which Mexican society has been hit by the militarization of public security is evidenced.

Through case studies, carried out mainly in the north of the country and one in the capital, the victims' agency is analyzed, who, in collaboration with civil society organizations and academics, act to redress human rights violations: forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, attacks on freedom of expression and forced displacement.

While some victims seek the truth, that is, to locate their “treasures”, others struggle for the recognition of the responsibility of the Mexican State before international actors and an unlikely justice. Fleeing and displacing are also ways of resisting, especially when facing the fear of victimization. Meanwhile, the hope remains of returning to the land and working to guarantee non-repetition. Such is the case of displaced journalists, who have only recently organized into a group.1

Militarization of public security and massive human rights violations

The four articles that make up this dossier are emphatic in pointing out the humanitarian balance of the misnamed war against drug trafficking, an unconventional war that is inscribed in the registry of new wars (Kaldor, 2001), where armed struggles take place within the states themselves due to their inability to face social decomposition; wars where non-regular armies are often fought. Mbembe (2012), cited by Robledo in this issue, highlights the global nature of the new wars that express: 1) an increasingly close relationship between politics and war, which implies a deep identification between political freedoms and security ; 2) a dramatic uncertainty about who the enemy is and the existence of a series of technologies and devices to identify him; 3) an asymmetric nature in the exercise of war power, which is exercised above all against civil society; 4) the technological multiplication of the capacity for destruction; 5) the structural character of these wars, which seek to destroy the basic conditions of the societies against which they are directed; 6) the proliferation of warriors who act oriented to the interests of the market, and 7) a war that not only looms over bodies but also over nature.

In Mexico, the Joint Operations carried out in certain regions, as a government strategy to confront the enemy called “drug trafficking” and later renamed “organized crime”, involved the deployment of the national armed forces. This, as May-ek Querales well underlines: “led to serious conflicts in the regions where it was implemented because it resulted in the presence of three armed actors on the territories: the police forces (federal, state and municipal), the army and / or navy, and organized crime ”.

Brenda Pérez and Montserrat Castillo, activists at the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights (CMDPDH), detail the humanitarian balance of this militarized strategy that exponentially increased direct violence against the civilian population. Beginning in 2006, Mexico experienced an avalanche of homicides, extrajudicial executions and disappearances, all serious human rights violations that the aforementioned authors present in detail. The press was not exempt from it. In this regard, Séverine Durin gives an account of the lethal forms of coercion used against the media in the Northeast. Based on several cases, the author gives an account of the violence to which the journalists were subjected: death threats, homicides, disappearances and attacks with high-powered weapons against the buildings of the regional press. The war, as Durin demonstrates, also took place in the communication sphere and placed journalists in the line of fire, so that the armed actors in the conflict sought to control the editorial line of the media; The State did so by signing agreements with the media in 2011 (Eiss, 2014), while illegal armed actors coerced them to hide casualties in their troops or communicate cruel actions through the television stations and sow terror in the population.

As a result of these human rights violations and criminal violence, Mexico experienced a new wave of forced migrations, some internal and which have not been recognized by the State, which reached 329,917 displaced persons in December 2017, according to the monitoring carried out. from the CMDPDH; others abroad, especially towards Texas, where activists, journalists and displaced persons from the Juárez Valley gathered around the figure of their lawyer and created Mexicans in Exile (see Querales).

Other victims, who feel "dead in life", carefully comb the land where their loved ones may have been buried by those who wanted to erase the evidence of their crime, and thus sow anxiety among the population. Disappearing a person's body, without allowing their relatives to give them a burial, is part of the pedagogy of cruelty that armed actors, legal and illegal, inflict on the civilian population, as Robledo points out: “Mexico has attended the breadth of the spectacle of suffering and cruelty, through the staging of various forms of extreme violence ”(Nahoum-Grappe, 2002). Perhaps the most perverse effort, and the one most sought by its perpetrators, is the one highlighted by Querales, for whom forced disappearances, executions on public roads, extrajudicial executions, blankets and threats written on public roads, and harassed and exhibited bodies on everyday routes, they are used to dismantle community senses and silence communities.

Internal enemies, structural violence and the dismantling of citizenship

From the perspective of Johan Galtung (1990), direct violence, which takes the form of homicides, disappearances and forced displacement, can only be understood in its relationship with structural violence and cultural violence, that is, the cultural and symbolic elements that justify structural violence and keep sectors of the population excluded from the benefits of the common. So what were the cultural, symbolic and ideological elements that legitimized the use of direct violence? And, in what way did it also lead to greater structural violence?

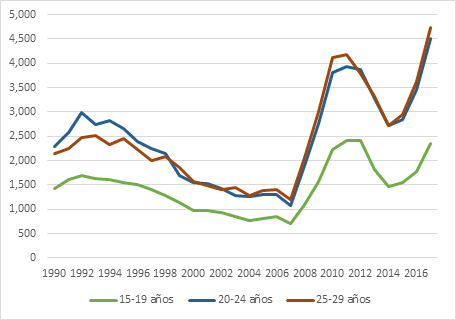

As I explained in other spaces (Durin, 2018), the construction of the figure of the “narco” as an internal enemy to be defeated by the military forces occurred towards the end of 2006. This intersects with negative representations about young men from popular media , and it is not anodyne that there are "hundreds of young men and women who have been denied their dignity" by their disappearance (Robledo) and that homicides have rebounded among young people between 15 and 29 years of age at this time. This phenomenon, which was classified as juvenicide (Valenzuela, 2015), shows the reinforcement of structural violence against the youth sector, especially men from popular media.

Table 1: Homicides in the population aged 15 to 29 in Mexico (1990-2017)

In turn, the fear of the ruling classes towards the popular sectors, which was activated during the 2006 electoral campaign, was transformed into a fear of the “narcos” during the post-election season, when the president-elect agreed with the US authorities on the Binational security strategy called the Mérida Initiative, similar to Plan Colombia (1999-2005), which not only implied an anti-drug strategy but also favored foreign investment in strategic sectors, technical advice for legal reforms, and tax incentives (Paley, 2012).

This mechanism of construction of internal enemies, who serve as scapegoats, is an ideological resource that Jacques Sémelin (2013) observed in the logic that led to the perpetration of massacres in Nazi Germany, Bosnia and Rwanda. They require political leaders who are capable of activating nationalistic sentiments, based on a desire to restore the lost greatness of the nation, and the identification of those responsible for the defeat that must be destroyed. In our case, the alterity of the "narco" was erected as the one that must be defeated, to the death if necessary. In accordance with this rhetoric, in January 2007, President Felipe Calderón appeared dressed as a military man in Apatzingán, Michoacán, where he declared to the armed forces that “I come today as Supreme Commander to recognize your work, to exhort them to continue firmly , surrender and tell them that we are with you ”(La Jornada, January 3, 2007). This is because “his government is determined to regain peace, not only in those entities, but in every region of Mexico that is threatened by organized crime. Although he reiterated that the fight is not an easy task nor will it be quick, as it will take a long time and will involve enormous resources from Mexicans, even the loss of lives ”(idem).

This strategy, which cost thousands of lives, rested on the stigmatization and persecution of a sector of the population, but not on the use of a judicial strategy to dismantle transnational companies that, with the complicity of the authorities, are dedicated to the sowing and transferring drugs. In addition, the nationalist plot of the discourse did not allow voices to arise against him, since it was to behave as a traitor, and it exposed citizens to the horror of armed violence in their areas of life. The terror practices of the armed actors in conflict were deployed against the population, especially affecting activists, journalists and community leaders (see Querales, Durin, and Pérez and Castillo). It contributed to dismantling citizenship, and as Pérez and Castillo argue, the fear of stigmatization and criminalization was a powerful factor against the organization of displaced people, so that these victims of the war on drug trafficking remained invisible.

The struggle for rehumanization

Despite extreme violence, terror, impunity and dehumanization embodied in the figure of someone who murders without mercy or disgraces and throws bodies on public roads as part of a grammar of violence that puts an end to the human condition (Reguillo, 2012), the victimized citizens acted, as evidenced by the texts that constitute this dossier.

Actions in favor of truth, justice, in the face of State violence and criminal violence, are ways of resisting dehumanization (Levi, 1987) that derives from the cruel ways of depriving life and hiding violations perpetrated by responsible state and non-state actors. The act of lovingly naming those who are sought, of referring to them as his "treasures", unlike the forensic and scientific terminology that "remains" prefers, illuminates the human dimension contained in his actions. The trackers of Fuente, Sinaloa, or the people who participate in the search brigades in Veracruz or Guerrero, in the face of the inaction of the State and the regime of impunity and not the truth, organize to find out what has happened to their relatives, and seek identification and restitution from a humanitarian perspective. Its strategy, which differs from those of other human rights groups and organizations, abandons all demands for justice and the designation of culprits, in order to avoid persecution by the authorities and to obtain their collaboration in identification tasks, which present enormous challenges in the actuality. Through citizen searches, they experience the restorative capacity of the act that rehumanizes by recreating social ties, and builds an emotional community of victims and allies (see Robledo).

This community reconnection also occurs among the exiled victims in El Paso, natives of the Juárez Valley and now members of Mexicans in Exile, who find in the organization a way to achieve a subjective reconnection, by narrating their traumatic experiences and transforming them into suffering. through intersubjective dialogue established in therapies, written letters and acts of protest. In addition to participating in the monthly meetings of the organization's members, the community reconnection operates by collaborating with human rights organizations, located in the border city of Juárez, and directing events towards American civil society (plays, protests, conferences press) to publicize human rights violations in Mexico. Thus, from the margins of the national State, they address various audiences, to demand recognition of the situation that prevails in their country and to demand justice (see Querales).

However, not all victims are grouped around a common goal, and in the case of displaced people (see Durin, Pérez and Castillo), the first impulse is to save their lives and does not give rise to meeting with people on an equal basis. of condition, especially when the displacements are individual or family, as happened in the case of the journalists interviewed by Durin. In addition, the coercion to which they were exposed was belatedly noticed by their colleagues in the center of the country, the headquarters of journalists 'organizations, and it took a few years before training was offered and journalists' networks were created in the Northeast, which allowed them to establish bases for a more supportive journalistic union in that region of the country. It should be noted that the creation of FEADLE,2 as well as the Protection Mechanism for Journalists and Human Rights Defenders in the Ministry of the Interior, in addition to being after the events of victimization suffered by journalists, it failed to redress the impunity in which the attacks against the press are found, For this reason, Mexico continues to be a very dangerous country for the exercise of journalism.3

In this sense, human rights organizations play a key role in making forced displacement visible, especially the CMDPDH, which created in 2014 a department dedicated to the issue in order to document cases and counteract the official narrative that denies the existence of the phenomenon. , despite the evidence presented by the National Human Rights Commission itself (2016). The work of systematic documentation of displacement cases, together with the monitoring of the press, gives an account of the magnitude of the phenomenon, and allows them to build reliable information, at the same time that they prepare strategic litigation and go before international human rights organizations.

Positions in tension: academia, organized civil society and the State

As a final reflection, the texts are written from different positions, from human rights organizations, such as the CMDPDH, the academy, and in collaboration with victims' groups and organizations. Robledo's text realizes the importance of deconstructing scientific knowledge and being attentive to the knowledge of people, victims, their expectations, in the face of a forensic science that dictates procedures, but also a science in which the expert witness can support the claims of victims.

Inevitably, tensions arise in the relationship that the victims weave with other actors, sometimes allies, other times not, that we are the academics, the State bureaucracies - which tend not to act and re-victimize, but have the means to identify the victims. “Treasures” found in citizen searches— and human rights organizations, which are fighting for new legislation, while following what is in force. From an anthropological perspective, it is worth remembering the importance of placing the dignity of the people with whom we work at the center, and also being aware of our own challenges in terms of caring for our lives. Today, networking is essential to act safely from the academic trench.

Bibliographic references

Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (2016). “Informe especial sobre Desplazamiento forzado Interno (DFI) en México”. Recuperado de http: //www.cndh.org.mx/sites/all/doc/Informes/Especiales/2016_IE_Desplazados.pdf, consultado el 10 de agosto de 2017.

Durin, Séverine (2018). “Víctimas sospechosas. Desplazamiento forzado, daño moral y testimonio”, Ponencia presentada en el VI Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales Las ciencias sociales y la agenda nacional organizado por el Consejo Mexicano de Ciencias Sociales, A.C, la Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí y El Colegio de San Luis, A.C. Centro Cultural Universitario Bicentenario, San Luis Potosí, SLP, del 19 al 23 de marzo de 2018.

Eiss, Paul K. (2014). “The narcomedia. A reader’s guide”. Latin American Perspectives, Issue 195, vol. 41, núm. 2, , pp. 78-98.

Galtung, Johan (1990). “Cultural violence”. Journal of Peace Research, vol. 27, núm. 3, pp. 291-305.

INEGI (2018). Estadísticas de mortalidad. Defunciones por homicidio. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/proyectos/bd/continuas/mortalidad/defuncioneshom.asp?s=est, consultado el 19 de diciembre de 2018.

Kaldor, Mary (2001) Las nuevas guerras. Violencia organizada en la era de la global. Barcelona: Tusquets.

La Jornada (2007). Claudia Herrera y Ernesto Martínez, “Vestido de militar, Calderón rinde ‘tributo’ a las fuerzas armadas”, 3 de enero.. Recuperado de http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2007/01/04/index.php?section=politica&article=003n1pol, consultado el 17 de octubre de 2016.

Levi, Primo (1987). Si c’est un homme. París: Juliard.

Mbembe, Achille (2012). “Necropolítica, una revisión crítica2”, en Helena Chávez Mac Gregor (curadora académica). Estética y violencia: necropolítica, militarización y vidas lloradas. México: Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo, pp. 130-139.

Nahoum-Grappe, Véronique (2002). “Anthropologie de la violence extrême: le crime de profanation”. Revue internationale des sciences sociales. núm. 174. pp. 601-609 .

Paley, Dawn (2012). “El capitalismo narco”. Recuperado de https://dawnpaley.ca/2012/08/20/el-capitalismo-narco/, consultado el 25 de octubre de 2016.

Reguillo, Rosana (2012). “De las violencias: caligrafía y gramática del horror”. Desacatos, núm. 40, septiembre-diciembre de 2012, pp. 33-46.

Reporteros sin Fronteras (2018). “Clasificación. Los datos de la clasificación de la libertad de prensa 2018”. Recuperado de https://rsf.org/es/datos-clasificacion, consultado el 19 de diciembre de 2018.

Sémelin, Jacques (2013). Purificar y destruir. Usos políticos de las masacres y genocidios. Buenos Aires: USAM EDITA Universidad Nacional de General de San Martín.

Valenzuela, José Manuel (coord.) (2015). Juvenecidio. Ayotzinapa y las vidas precarias en América Latina y España. México: Ned Ediciones/ITESO/El Colef.