Uses and meanings of the female portrait in the Guatemalan press, 1890-1924. Making social history with images: a methodological proposal.

- Paulina Pezzat Sánchez

- ― see biodata

Uses and meanings of the female portrait in the Guatemalan press, 1890-1924. Making social history with images: a methodological proposal.1

Receipt: September 23, 2024

Acceptance: January 27, 2025

holds a B.A. in History from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. D. in History from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ciesas Peninsular headquarters, where she has developed studies of the image in Oaxaca and Guatemala with an intersectional approach. She has emphasized the revaluation of photographic images as sources for history and historiographic dialogues in Latin America.

Abstract

At the end of the xixThe photographic image was incorporated into the world of print and new markets were opened to market printed works as well as images. The selection of which images to publish and their meaning was a decision mediated by the social conventions of the time, notions of race and gender, the class aspirations of intellectual elites and a project of national identity. This article proposes to analyze the visual economy of female portraiture in Guatemala published in illustrated magazines between 1900 and 1920. The objective is to analyze the visual discourses on Guatemalan women and to present a methodological proposal for the analysis of photographic images.

Keywords: visual economy, Photography, PRINTED MEDIA, female portrait

uses and meanings of the female portrait in the guatemalan press (1890-1924): proposing a methodology for a social history with images.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the print world incorporated photographs, opening new markets for the sale of both printed works and images. The decisions on what images to publish -and their intended meanings- responded to social conventions, prevailing notions of race and gender, the class aspirations of the intellectual elites, and a project to craft a national identity. This article analyzes the visual economy of the female portrait in Guatemala as published in illustrated magazines between 1900 and 1920. Besides exploring visual discourses about Guatemalan women, it lays out a methodology for analyzing photographs.

Keywords: female portrait, photography, print media, visual economy, gender.

Printed media are a rich documentary source and little worked for the development of visual studies. In the case of Guatemala, it allows diversifying sources to make a visual history. In this article we will make a methodological proposal for historical research with images published in the Guatemalan press between 1890 and 1924, specifically female portraits. I am interested in analyzing the uses and meanings of portraits of women published in newspapers, magazines and illustrated books, and their role in the configuration of a Guatemalan national identity.

Since the late 1880s, printers incorporated photoengravings into their pages and, in this way, the print media became one of the main channels for the mass circulation of images. Visual anthropologist Deborah Poole coined the term visual economy to explain the organization of people, ideas and objects around the field of the visual. Such organization is woven from social and power relations according to notions of race, gender and ethnicity (Poole, 1997: 8). The visual economy is understood as the process of construction of alterities, imaginaries and stereotypes through the production, uses, signification and valorization of photographic objects. In this regard, I consider that historiography has paid little attention to the circulation of images in printed media and to the evaluation of the impact it had on the hierarchization of Latin American nation-states at the beginning of the 20th century (Poole, 1997: 8). xx. Therefore, in this article I will concentrate only on the uses and significance of the female portrait in the Guatemalan press.

Since its origin in the middle of the xixportraits were objects that remained in the private and family sphere. However, when reviewing the Guatemalan press of the end of the century xix and early xxIn the case of portraits of young ladino women from the country's oligarchic families, we note the presence of portraits of young ladino women from the country's oligarchic families. As these were photographs whose use was mainly restricted to the private sphere, it is worth asking the following questions: what criteria were followed in the selection of portraits published in newspapers and illustrated magazines; what uses and meanings were assigned to these portraits; how did gender, class and race intervene in the publications; and how did they contribute to the construction of national stereotypes and imaginaries?

I am interested in understanding the categories of gender, race, class and ethnicity, not as fixed and timeless labels. Furthermore, I argue that notions around gender, race and class defined not only the forms of representation, but also those of circulation. I also argue that photography was a key tool for the creation and consolidation of these categories, congruent with a liberal national project.

In a methodological aspect, I propose how to systematize a set of images that are not part of the same collection, but are included in an even larger documentary source. The objective of this article is to make a methodological proposal for the analysis of photographic images, in this case of printed female portraits, based on criteria of formal structure.

Theoretical and methodological proposal

The review of photogravures in the Guatemalan press and in illustrated books published between 1890 and 1915 composes a corpus of approximately 500 images that include landscapes, urban views, architecture, coffee farms and portraits. Particularly striking is the space devoted to female portraits, which made me wonder how they went from being private objects to public diffusion. From the set of 14 publications consulted, I selected those that include portraits of women. These publications are the following: Lessons on Geography of Central America preceded by notions of universal geography. (1890-1900 approx.), the illustrated magazine The Locomotive (1908), the newspaper El Imparcial (1924), y The Blue Book of Guatemala (1915). Although the purposes and contents are diverse, they all share the dissemination of portraits of Guatemalan women in a context that sought to project an idea of a Guatemalan nation. This documentary corpus of 98 female portraits problematized the characteristics that define a portrait and how the social context is reflected in them.

The documentary body of portraits published in the press was organized following the principles of formal structure. I retake the term formal structure from Fernando Aguayo and Julieta Martínez, who refer to the way in which the formal elements of the image are arranged based on the analysis of archival documentation and photographic production contexts of the time (Aguayo, 2012: 218).

It is important not to confuse formal structure with photographic themes or photographic genres. Different photographic images may have shared elements or represent the same subject; however, the arrangement of those elements or the way in which the subject is represented are of different compositions. As for genres, Valérie Picaudé defines them as "a type of images that have common qualities and a mental category according to which the perception of images is regulated [...] it allows us to classify images according to essential criteria" (Picaudé, 2001: 22-23). The point is that these criteria for defining photographic genres were intended to give continuity to artistic practice and, as Jean-Marie Schaeffer points out, the generic parameters of photography should respond to functional aspects and their uses, but not to aesthetic aspects (Schaeffer, 2004: 17).

Portraiture was originally a pictorial genre of symbolic self-representation and, as such, it reproduces visual conventions established in each era and influenced by its context (Burke, 2005: 30). The nineteenth-century photographic portrait emerged within the European bourgeoisie as a means of class reaffirmation by incorporating elements associated with their aesthetics and taste, reflected in the props, furnishings, backgrounds and even poses. These characteristics were maintained until the middle of the century. xx.2 The forms of representation of photographic portraits diversified, as did their uses. In order to understand the logics behind the publications of female portraits it is important to know the social context of Guatemala, specifically the criteria of social hierarchization (Pezzat, 2021: 33).3

Photographic studios at the end of the century xix were considered sacred spaces, to which people went as a way to reaffirm their status with a particular behavior. As Poole explains, this ritualization of the photographic space unintentionally contributed to the mass production of type photographs as a way of understanding the constitution of "races" (Poole, 1999: 237). While portraits reaffirmed individual identity, photographs of types were the objective and visible proof of human types divided into races.

Social categorization in Guatemala at the end of the nineteenth century

During the conservative governments in Guatemala (1838-1871), the nation-state scheme was simplified to the triad Creole-Ladino-Indian, and with the liberals it was further reduced to Ladino-Indian. The term ladino has not remained homogeneous throughout the centuries, but must be understood according to the conjunctures of each period and the projects of nationhood. In the liberal national project, the process of ladinization was understood as the homogenization of ethnic diversity under the category of ladino. This included Creoles, Chinese, Europeans, etc. (Taracena, 2002: 20). Martha Elena Casaús considers that, in the Guatemalan liberal project, the Indian had to undergo a conversion to both Creole and Ladino. Criollo because he had to imitate Western patterns of behavior and dress, and ladino because it was part of the acculturation process to lose his ethnic identity as an Indian and become a ladino (Casaús, 1999: 790). Beginning in the xxThe project of ladinization by western acculturation of the Indian was replaced by eugenic projects. It is then that Guatemalan intellectuals speak of racial whitening or even of the extermination of the indigenous race (Casaús, 1999: 799).

In the face of the polarization of the Indian-Ladino binomial and the mestizo aberration of the Guatemalan model, the mengalas represented the ethnic ambiguity that liberal politicians and intellectuals feared so much. According to anthropologist Rubén Reina, the mengalas formed the third group in the social structure of the municipality of Chinautla (department of Guatemala), although there were also mengalas in other towns. The majority group were indigenous people, who as small landowners were dedicated to the cultivation of milpa (cornfields). At the other end of the social scale in Chinautla were the recently arrived ladinos. They were generally entrepreneurs or businessmen interested in promoting modernization. Finally, the mengalas were a demographic minority, but economically important.

The mengalas had a history dating back to the monarchic period, whose characteristics allowed them to move easily in both indigenous and ladino social circles (Reina, 1959: 15). Some mengalas spoke poqomam and were linked to indigenous people by ties of compadrazgo, and even danced according to their customs. However, they could also lead a ladino lifestyle and related to them (Reina, 1959: 16).

The aspirations of racial whitening in Guatemalan society were reflected in the illustrated press and in printed books, specifically in the ways women were visually represented. The selection of which women to show and what meanings were given to their images evidences the standards of feminine beauty that sought to consolidate as characteristic of a ladinized, non-indigenous or in the process of ladinizing Guatemala.

The photoengraving revolution

In terms of Philllipe Dubois, a photograph is a trace, a vestige of the existence of that object or subject that was frozen in time when it was placed in front of the lens of a photographic camera. Without this referent, the photograph would not exist, and this is what Dubois calls an indexical character, with which the referent becomes an index, distinguishing the photograph from the icon or symbol (Dubois, 1986: 56).

The singularity of which Dubois speaks is that unique and unrepeatable instant in time and space, with the capacity to reproduce itself mechanically to infinity. The multiplicity of copies of the same image comes from an original and singular photographic object: the negative, the daguerreotype, the polaroid photo, etc. These objects represent the print and there is only one, the rest are photos of photos or "metaphotos", as Dubois would say. Each image reproduced from that original photogram then operates as a sign that refers to the object or subject denoted (Dubois, 1986: 66-67).

In this sense, photoengravings are "metaphotos", the result of a photomechanical process to make a print from a photographic image or "cliché" (Valdez, 2014: 35). Their quality was very poor, as was their cost, which allowed for an exponential increase in the mechanical reproduction of images by incorporating it into the print market. However, as Julieta Ortiz explains, photoengraving set a precedent for the consolidation of a visual language, by making it possible to reach a mass audience (Ortiz, 2003; 25).

In 1892, the newspaper The News announced that a section titled "Siluetas femeniles" would be included, dedicated to portraits of young women from the capital of Guatemala made by the Palacio de Artes studio, then owned by E. J. Kildare and Alberto Valdeavellano. However, this did not happen until years later with the boom of illustrated magazines as early as the 1900s, although their uses extended to official books such as The blue book, to national newspapers and occasionally to educational books.

Of the set of images included in these works, there are illustrations of landscapes, urban views of Guatemala City and some Central American cities, portraits of politicians and female portraits. In most cases, the selection of images had no relation to the textual content of the publication and only sought to illustrate the progress of urban life and Guatemalan society. Within the subgroup of female portraits, we can divide them into two. The first subgroup corresponds to conventional portraits of young ladina women, with the exception of an image of a Mengala woman. The second subgroup consists of group portraits of guadalupanas. Before analyzing each, let us explore their characteristics and social historical function.

Portraiture as a means of individual and identity expression.

More recent studies with a gender focus have demonstrated the importance of the role of photography in the consolidation of modern ideas of femininity and have evidenced the active participation of women in the construction of their image (Onfray, 2016). However, it is worth questioning the application of photographic self-representations in the reaffirmation of a position of privilege. The act of self-representation as a practice conditioned by aesthetic and social conventions, both collective and individual, can be considered a thermometer on how the political encompassed the sphere of the private.

In Guatemala, portraits of political and military leaders and wealthy families symbolized the political power of the conservative Guatemalan elite (Taracena, 2005: 9). However, it was not until the liberal governments, particularly that of Manuel Estrada Cabrera after 1898, that the photographic image was used as part of a visual discourse for political purposes of power and prestige, not only to project an idea of the country, but also to exalt the personal image of the rulers. This was a popular phenomenon in Latin America, as José Antonio Navarrete explains, where the idea of modernity implied imitating what was done in Europe and "modeling" the inhabitants as citizens.

The parameter was the idea of a bourgeois, urban, literate man, as described by the Manual of civility and good manners (1853) by Manuel Antonio Carreño, which was widely disseminated for decades. The manual was designed for an urban and Catholic society, made up of mononuclear families governed by Christian values (Carreño, 1853). According to Navarrete, this type of manuals established the qualities to be followed by individuals who were members of a "civilized" culture, but they also expressed the nineteenth-century society's awareness "of the body as a spectacle, of its authorized exhibition regulated by the laws of sociability" (Navarrete, 2017: 61-62). Thus, through portraiture, subjects were represented with aesthetic and social conventions to reaffirm their social position. As for the female portrait, this was a ritualization of femininity in accordance with the gender roles of the time by highlighting the values that women should carry, such as abnegation, compassion, beauty, tenderness and delicacy, among others (Rodríguez, 2012: 245).

From the composition of the image, the portraits can be confused with photographs of popular types, very common at the time; photographs recording trades or even, in some cases, with ethnographic photographs. By the latter, I am referring to those photographs taken with scientific pretensions of recording cultures or for administrative and bureaucratic purposes. In general terms, the four subgenres mentioned are photographs of individuals, couples or groups, whose objective is to capture the subjects. The choice of framing is not innocent; it implies a web of representations linked to the social, political and cultural. They are windows that allow us to peek into power relations traversed by gender, class and racial categorization. In the case of the photographs of popular types or trades, the purpose was not to capture the individuality of the subjects, but to construct a network of national symbols that would conjugate the social body by abstracting general characteristics. This process, explains José Antonio Navarrete, contributed to romanticize the policies of exclusion, on the one hand, and, on the other, that of nuancing social and ethnic inequalities crossed by a racialist thought with which society was hierarchized (Navarrete, 2017: 49).

There are elements linked to the language of photographic technique that are key to determining the formal structure of portraits. Frames may be close-up, half-frame or full-length; subjects may be posed frontally, in profile or three-quarter profile and may be standing or seated. The rest of the characteristics, such as poses, gestures, clothing and decorative elements, depend on each production context and the purposes of the portrayed. This is one of the main points that establish the differences between portraits, popular types, trade record photographs and ethnographic photographs. Other elements of distinction are the different uses and meanings assigned to them during their circulation.

So, what distinguishes portraits from other themes and forms of photographing women? Researchers Solange Ferraz and Vania Carneiro define them as a means used by social groups "to represent themselves" (Carneiro, 2005: 271). That is, the portrayed is aware that a record of his or her image will be made. On the other hand, photographs of types sought precisely the opposite: to strip the subjects of their individuality, reduce them to representatives of a collectivity and highlight particular elements that distinguish a culture from the rest. Despite the above, integrated into a visual economy, the uses given to these portraits could modify their original meaning for which they were created.

Returning to Monique Scheer's proposal, in which she addresses emotions as bodily practices, it is possible to give an interpretation to the portraits by recovering their subjective character, in which the body is connected to cognitive processes and the agent externalizes her emotions through practice (Scheer, 2012: 200). The selection of clothing and poses were actions assumed as part of the ritual of photographing oneself and of femininity. Going to the photographic studio was not an everyday event and, as such, the clothing chosen corresponded to what was expected of that ceremony. The position of the body was determined by the technical aspects offered by photography (speed of exposure times, light, etc.), but also by the image to be projected. If this issue is taken into consideration, it is possible to identify patterns and differences of class, race and gender.

Ethnicity in portraits. The "pretty Indian" and the guadalupanas of Guatemala.

The phenomenon of Guadalupanismo in Guatemala spread as a result of its geographic proximity to Mexico. However, as historian Arturo Taracena explains, in the Central American country it did not take root as part of a nationalist project, nor was it associated with an idea of mestizaje, as was the case in Mexico. Its development has been marked by different political and social situations over several centuries (Taracena, 2008: 14).

Among the different forms of expression that Taracena identified in the evolution of Guadeloupianism in Guatemala, one of the oldest practices is that of dressing babies as "Juan Diegos".4 and "Marías" from the first months of life until the age of seven, every December 12. According to the author, this practice dates back 214 years and emerged in Antigua Guatemala, and since then it became a tradition among the middle classes of the capital and Antigua to go to the shrines dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe with their children "disguised" (Taracena, 2008: 132). The historian emphasizes the term disguise, since dressing the children of indigenous people did not imply assuming, neither temporarily nor symbolically, an ethnic identity, but rather that the clothing served "as an artifice to obtain Marian favor" (Taracena, 2008: 14).

The Guatemalan press at the turn of the century xix and early xx followed up on the practice of dressing children as "Juan Diegos" and "Marías", which was promoted among non-indigenous young women in the capital. The newspapers of the time invited the young women with the incentive of publishing their photographs in their pages (Taracena, 2008: 155). In the newspaper El Imparcial In 1924, an invitation was extended to the "rezado" of December 12 with the privilege of "dressing our girls and boys -and even the older ones- as Indians, who thus appear charming".5

The prayers were accompanied by the illumination of the streets, fireworks and the passing of young people dressed in their costumes. The occasion was used to celebrate the "pretty Indian", as they referred to the ladinas "disguised" as Indians.

Day of the Guadalupana [...] Day of the counterfeit wet nurses and oxygen-blonde Indians. Day of your pretty Indian, of the color of the porrones, wet with fresh water [...] Why do you disguise yourself naturally when your smile is esoterically yankiyogi, theosophical, and says of wisdom, of the dark Demiurge and of the academies of philosophy and piano of the United States. You dance the fox-trot, of the chiclet girls and not the rumbustious and unbound sound of the bronze hierodules, that in Atitlán, lit their beauty, in the cabarets of stars when drunk of octle, they waited for the light of Tonalí, lying down and mourning in the elongated shadow of the idols.

And in this return to the past, to the regional page, you feel good, inside the comfort of your güipil, with desires to squat in front of a grinding stone, to make corn tortillas by patting them strongly, in the joy of your resurrection. And in this fluttering of macaws pretending the joyful costumes, I have discovered you, full of nephrite chalchihuites, with powerful and naked arms, capable of making the ringed lust of the chanes tangle in them, in a group of sacred serpents.6

The above quotation conjugates a series of stereotypes about indigenous women. For example, the expression "false wet nurses" expresses that this was a trade exclusive to indigenous women and the phrase "blonde oxygen Indians" reinforces the disguised nature of the dress, worn by white women. When the author indicates that the tradition of dressing as an Indian is a return to the past, which at the same time endures in the daily life of the indigenous women, he refers to a backwardness as if they were static cultures in time. Not only that, the quote also carries a sexual charge, in phrases such as the comfort of the huipil, the position to use the grinding stone, "the powerful and naked arms" when making tortillas, which, according to the author, are capable of entangling "the ringed lust of the chanes, in a group of sacred serpents".7 Implying that these elements arouse passions.

The figure of the Virgin Mary was central to the consolidation of a Catholic culture. In the case of Mexico, it was key to the development of a national identity, and in Guatemala, its fervor was practiced differently according to the position in the social structure. In any case, the Virgin was the model of woman promoted by the Catholic Church as virgin, wife and mother of Jesus. Based on these values and ideas, a control of female behavior and sexuality was justified, and those who did not fit this model, in the eyes of the Church and society, did not fall into the category of "good women" (Ericastilla, 1997: 36). It is not surprising then that the cult of Guadalupe was associated with the idea of femininity and merged with photographic self-representations.

The following illustration is an example of the scenes that were published in the press to commemorate this date. It shows a group of teenagers with their respective costumes, their baskets of fruit or pitcher as the indigenous women used to carry. Even one of them, in the lower right corner, carries a doll as a baby. These elements were part of the stereotype of the indigenous women that was fed through photography and reproduced in this type of customs.

During the same decades, in post-revolutionary Mexico, the idea of mestizaje was cemented as a condition for national cohesion, which led to a folklorization of the identity elements of indigenous peoples. A popular practice among Mexican city women was to be photographed wearing traditional costumes from certain regions of the country. For example, the Chinese poblana costume or the Tehuana costume. Poole interprets this phenomenon as part of a process of integrating "las patrias chicas", that is, the different regional identities, to make them national. In this sense, the characteristic form of dress of ethnic groups, converted into "typical costumes", became a fashion among urban groups (Poole, 2004: 68).

In Guatemala there was also a process of folklorization of indigenous peoples, although with its own particularities. One of the aspects that could distinguish it from the Mexican examples is that the photographs of the guadalupanas did not "perform the indigenity", but the guadalupana devotion, which implicitly associated the folklorization. Unlike the Mexican case, in which the tehuana or china poblana costumes were appropriated by groups other than Zapotecs, the portraits of the Guatemalan guadalupanas refer to the imaginary of the "Indian" or rather of the "pretty Indian", using cobanera costumes or the closest thing to the Mayan K'iche costume, which, as Taracena illustrates, also reflects the place of the "Indian" in the Guatemalan national imaginary.

The hairstyles also mark a distancing of the portrayed women from an ethnic identity linked to the indigenous people of Guatemala. In the studio portraits of Quetzaltenango-based photographer Tomás Zanotti (1900-1950) of K'iches, Kaqchikel, Mam and Poqoman women, all have long hair tied back with one or two braids.8 While young ladino women adopted the "bob" style popular in the twenties or long hair, but gathered in a chongo. This fashion in hairstyles was evidenced in the chronicles of El Imparcial on the commemoration of December 12.

The heads are adorned not with exotic feathers and flowers, but with the high tun-tun or with the tangled chojop. To place these today, it has been necessary to appeal to the false braids because the tyranny of the fashion for days that made suppress of the feminine heads the long hair of which our Indians, the true ones, the authentic ones, those that take calloused the hands by the daily work of the milling and know the pain of the life of the ranch, have not still dispensed with. The hands today instead of bags of toilet and colorful umbrellas carry crude brooms or baskets with fruits. The pretty Indian woman passes by, attracting all eyes, under the triumphal arches of the Guadalupe neighborhood. Today she wears that dress as a tribute and as a coquetry. The homage is for the beloved virgin to whom she will pray with fervor in the sanctuary and who on a day like today wore the indigenous dress in the apparition. The coquetry is for the humans, for those who have to contemplate in the streets the beautiful Indian who wears the indigenous dress, the true costume of lights.9

This reinforces the idea that the intention of dressing as indigenous was not to assume or appropriate this identity, but to participate in the folklorization that surrounded Guadalupanismo, but without shedding its social quality. The quotation confirms the double meaning of indigenous dress: that of homage to the virgin and that of coquetry, as "pretty Indians".

It is interesting to note the different ideals of beauty that each country sought to promote, according to its national project. In Mexico, in 1921, the beauty contest "La india bonita" was held, with the supposed purpose of celebrating rural and indigenous identity in an attempt to establish a rupture with the Porfiriato discourse that belittled the rural. However, judging by historian Adriana Zavala, this type of event actually gave continuity to a public discourse in which the transition of the rural or indigenous woman arriving to an urban environment was represented. One of the continuities from the Porfirian feminine ideal to a post-revolutionary one was "the fascination of the male intellectual with the trope of the rural woman as a repository of cultural and feminine purity" (Zavala, 2006: 151).

In Guatemala it is clear that the "pretty Indians" were the ladino women disguised as Indians and not the real Indians. I consider that the indigenous disguise was used to express a coquetry that in normal conditions was frowned upon. In the understanding that a purity of femininity was promoted, ladina women had to behave demurely and be careful not to arouse passions. Appearing disguised as indigenous women lent itself to an interpretation of exercising a supposed coquetry and even to being eroticized, as evidenced in the quotation from El Imparcial.

Female portraits in print media

The researcher Elsa Muñiz explains that the representations of the feminine and masculine were related to the understanding of a social order, which was structured with the construction and modeling of the sexed body, crossed by cultural notions that turned it into gender, that is, enculturated body (Muñiz, 2002: 13). In this regard, I argue that visual culture was one of the means by which such notions were promoted and rooted. Moreover, magazines and illustrated books made a careful selection of portraits that reflected these generic ideals.

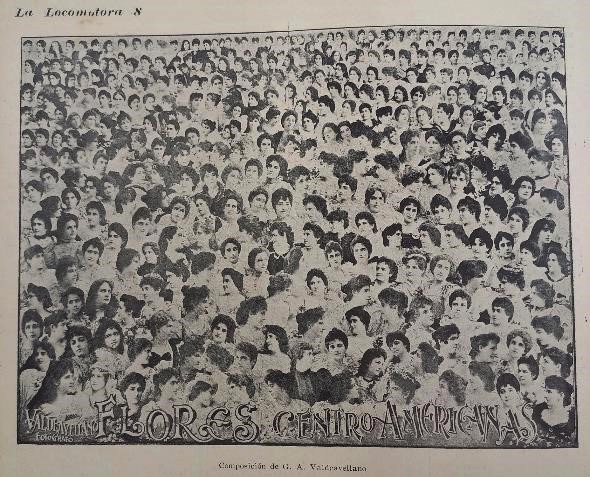

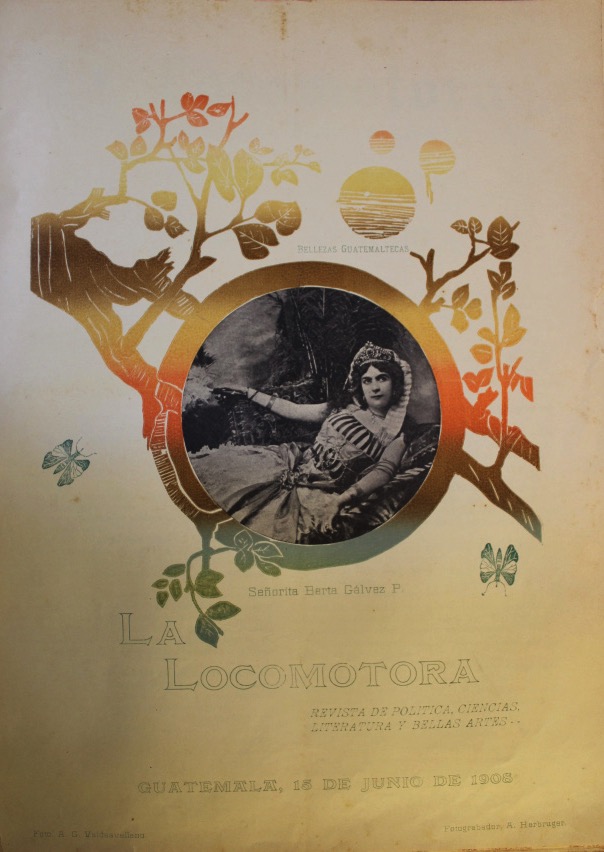

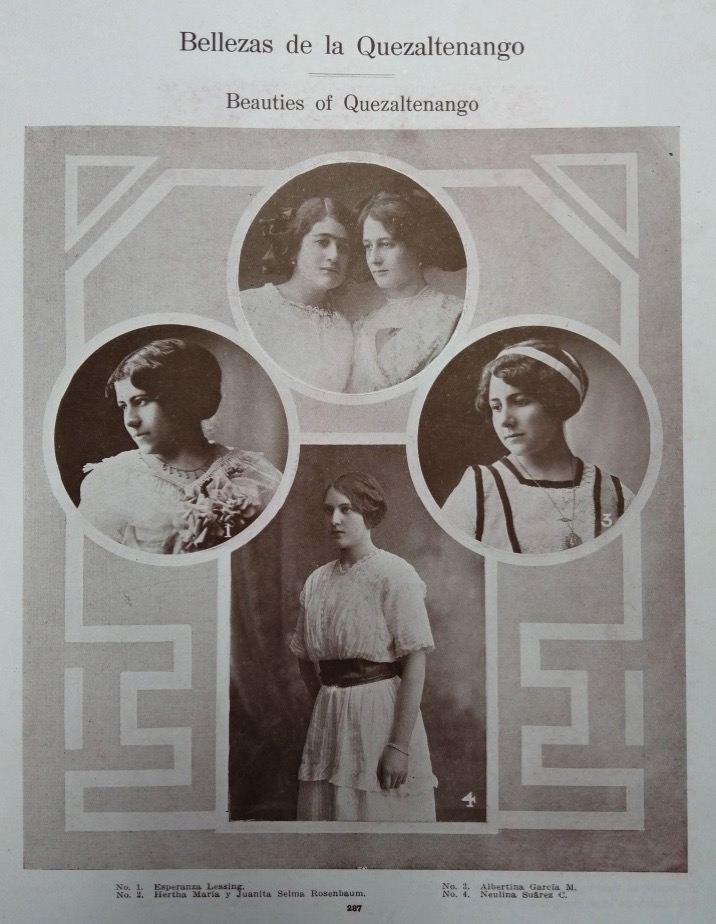

In the magazine The Locomotive (1907-1908) was illustrated with photographic compositions by the officialist photographer Alberto G. Valdeavellano, which consisted of montages with views of the city adorned with designs art nouveau. The contents were also accompanied by portraits of politicians and military men and a section was dedicated to "Guatemalan Beauties" or "Central American Flowers". The text and illustrations were rarely related and the identities of the young women were seldom indicated. Valdeavellano's photographic studios were among the most popular, so it is possible that he used material from his extensive collection to create compositions such as the one shown in image 2.

In the June 1908 edition, the cover was illustrated with Miss Berta Gálvez P., who posed for her portrait in a European aristocratic costume, as a performative expression of the aspirations of the Guatemalan elites to simulate a "high" culture.

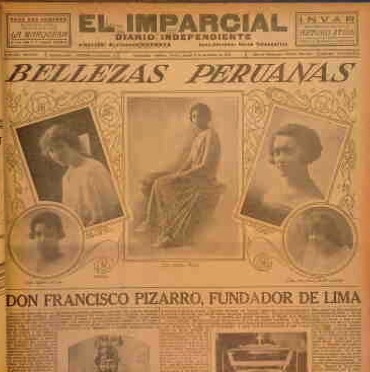

The inclusion of photos of women remained constant for several decades in the press. At El ImparcialIn addition to covering the guadalupanas, portraits of Guatemalan ladinas and occasionally foreigners were published daily. In the December 9, 1924 issue, the cover was dedicated to Peru on the occasion of the commemoration of the Battle of Ayacucho.10 In the middle of the page was published a biography of Francisco Pizarro, considered the founder of the city of Lima. The second half was occupied by "Peruvian Beauties"..

The content and illustrations have no relation to the Battle of Ayacucho, which is not mentioned. Not only that, a semblance of the main conqueror of the kingdom of Peru is made. As for the images in question, the insertion of "Peruvian beauties" indicates that this was a generalized practice. Moreover, it is striking that, as in Guatemala, Peru's ideal of beauty is white women, in a country with a high percentage of indigenous population.

Back in Guatemala, I will delve more deeply into the case of the Blue book (1915) as an illustrative example of a visual economy of portraits, designed for the foreign observer. I use the term "observer" in masculine because it was precisely a masculinized gaze towards whom the production of these works was directed. The Blue book was a work to promote foreign investment in Guatemala, so a careful selection was made of what was to be projected about the country. Its purpose was "to offer the foreign capitalist and tourist, as well as the son of Guatemala, an authentic exposition of the state of progress that this beautiful and pleasant country has reached".11

The portraits of women were included in the book for three purposes. First, to present some professional women. Secondly, to show women of the ruling class posing in portraits with their families. Finally, to showcase the "beauties of Guatemala". The latter was a section of the book in which portraits of young ladies from the main cities of the country were arranged to highlight their beauty. For this purpose, the popular format of compositions was used again, where a set of photogravures were distributed on a single page with an attractive design. Indigenous women also figured in this book, although in other sections of the book, which I will refer to in the following sections.

In the section "Intellectuality of Guatemala" there is a journey through the history of literature. It mentions the main writers and some works of historical relevance in each of the stages considered important up to that time, from the conquest, the monarchic period and the century xix. They affirm that, before 1871, the horizon of knowledge was opened for women, because before that time their life was governed by a colonial system: "that is, they were devoted exclusively to the chores of the house, they were kept dedicated to part of these offices, only to prayer, and there were few, it can be said that only those of the main families, who knew how to read and write".12 Among some of the intellectuals named are the poet Josefa García Granados, the historian and prose writer Natalia Gorriz, the sisters Jesús and Vicenta Laparra de la Cerda, founders of the newspapers Women's Voice (1885) y El Ideal (1887-1888).13

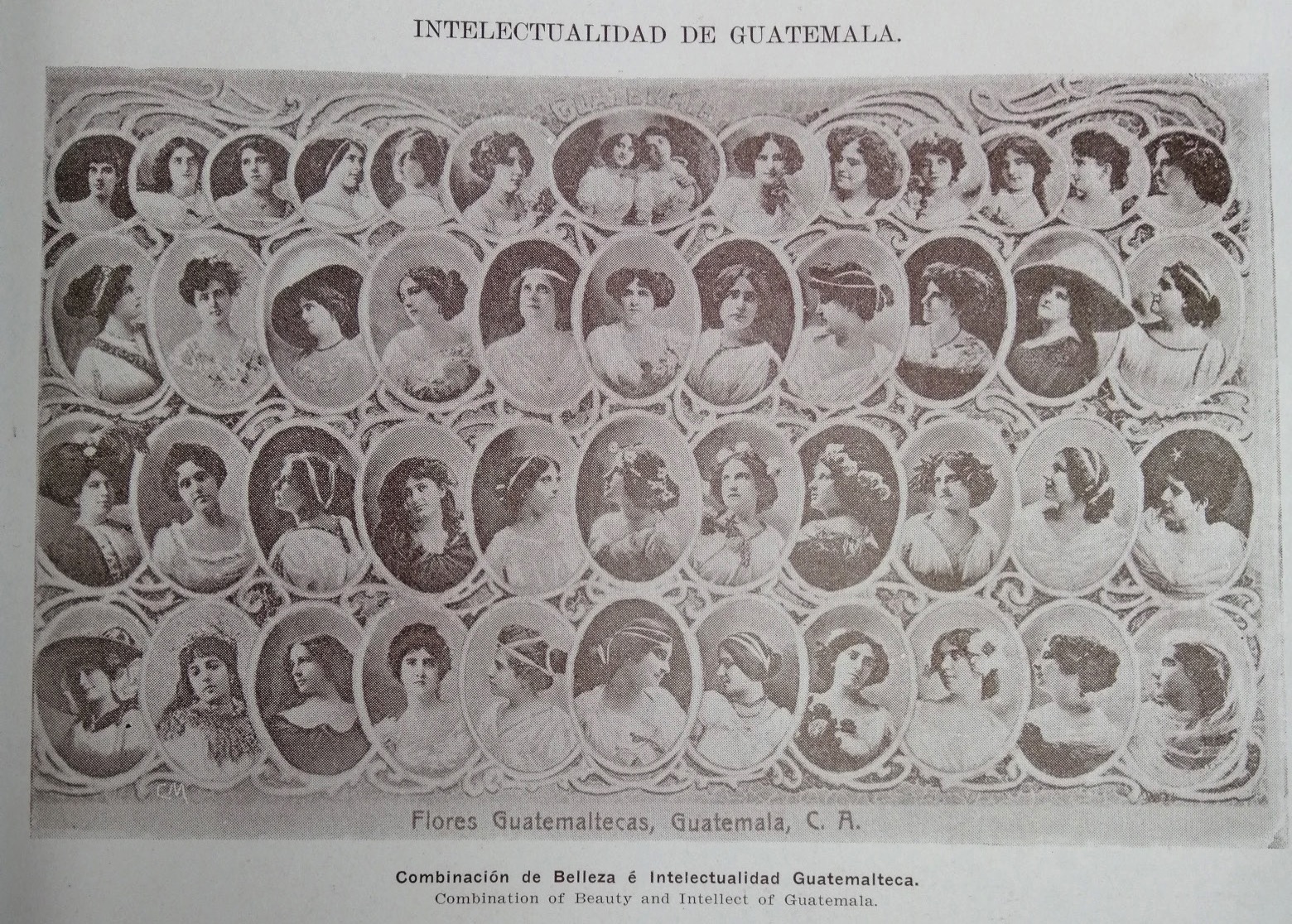

To illustrate the intellectuality of Guatemala, a montage of 46 oval-shaped close-up portraits of young women was made under the title "Combination of Guatemalan beauty and intellectuality".

In fact, the collage The portrait photography is not related to the content of the pages; moreover, none of the women are identified. The shots are short, in profile and oval cut to highlight the young women with colorful ornaments, such as necklaces, large hats or flower headdresses and voluminous hairstyles. Most of them have a sharp face, with fine features and very white complexion.

Miss Helena Valladares de la Vega, originally from Guatemala City, was described as follows: "Her sculptural figure transports us to the gallant time of the Louises of France, when Watteau painted his divine Shepherdesses, the blond viscounts quarreled over loves and the courtly abbots stripped madrigals at the feet of the Marquesas." With the above quote it is understood that the parameter for measuring feminine beauty sought in the contest were those features that referred to a Frenchified aesthetic.14

Another resource to show more portraits of young ladies was to dedicate a page to showcase "beauties" from the capital, Antigua, Quetzaltenango and Cobán. Each young lady portrayed is presented with her first and last name. Most of them were daughters of doctors, writers or businessmen and it was emphasized that they were young ladies. The composition sought to perpetuate a resemblance to bust sculptures that alluded to a classical or neoclassical style.

From what has been exposed so far, the Guatemalan feminine beauty that was promoted was totally bleached, not only in a literal sense because of the color of the women's skin, but also in the way they were represented. In the portraits that were disseminated in the Blue book a bourgeois aesthetic was exploited to the maximum (see image 6). In this sense, the idealized representation of Guatemalan women implied the demarcation of the indigenous. To such an extent that no Guatemalan national type with an indigenous ethnicity was promoted or consolidated, in any case, efforts were directed towards its concealment.

Portraits of the mengalas

The methodological proposal I present here includes not only the analysis of the overrepresented, but also evidences the absences, gaps and the underexposed. While indigenous women would not fall within the beauty standards of visual discourses, it is worth questioning the low presence of other subaltern identities such as mengalas in print media.

The mengala costume consists of a long and wide skirt to the ankle, tied at the waist by two ribbons whose color varied according to age. The blouse was usually long-sleeved and puffed up to the elbow or wrist, adorned with lace. Under the skirt they wore starched fustanes or naguas to give volume. Other accessories included an apron for the front part of the skirt; a blanket tightener for the bust; a leggings from the waist to the ankles; thread and silk stockings, shawls and scarves for the cold. Traditionally they wore black boots with lugs, although many went barefoot. Their hair was arranged in two braids intertwined with colored ribbons. For jewelry, they used to wear large earrings and necklaces, preferably made of gold or silver (Escobar, 2017).

This fashion is said to date back to the monarchic period, as it was how mestizas were identified. However, its use extended until around 1890 and reached greater popularity during the regime of Manuel Estrada Cabrera. Over time, the term took root to identify women who had a Spanish-influenced way of dressing, and by the xx was used to refer to women of mestizo origin who wore this garment as a regional costume. Anthropologist Judith Samayoa tells us that the mengalas were independent women who, thanks to their production of sweets, achieved a certain economic stability derived from the tourism that came to Amatitlán. Many of them were hired as cooks for the recreational houses on the shores of the lake of the same name (Chajón, 2007: 3).

During my research in printed sources I found only one representation of mengalas. In the book Lessons on the geography of Central America some engravings with the Indian types of Guatemala were included. The illustrations are identified according to the place of origin. For example, "Indios de Santa María de Jesús", "India de la Antigua", "Indígena de Mixco", etc. The way in which the mengala in image 7 is identified as a "woman of the people" is significant, since its definition is ambiguous. The term as such does not directly refer to an ethnic ascription, but its use does assign a class condition. To begin with, the term indígena or india is eliminated, indicating that the mengalas had transcended that category. With the word "pueblo", it refers to the fact that they still belonged to the popular majorities. As for the illustration, the engraving shows the face of the young woman, who wears the traditional mengala costume, with long frizzy hair, leaning on a bureau with a vase, which refers to studio portraits.

The mengalas are reminiscent of the Bolivian cholas described by Deborah Poole in Vision, Race and Modernity (1997), in his analysis of the album donated to the Geographical Society of Paris on June 27, 1885 by Dr. L. C. Thibon, Consul of Bolivia in Brussels. The album contains views of the country, portraits of the upper class and politicians, and business cards with South American types such as gauchos and national types of Bolivia. Included among the latter were 32 cards of cholas, almost all of them in the same pose very similar to image 7.

Cholas were the name given to women of indigenous origin who adopted a Spanish or urban form of dress. They could also be mestizo or not (Poole, 1997: 126). Like the Peruvian tapadas, the Bolivian cholas had a fluid identity, as they could not be pigeonholed into a racial category, nor did they practice a single trade, transcending the definitions of white, mestizo and Indian. Even clothing and jewelry could represent wealth, transgressing class. As such, they were not bound to the rules of the bourgeois class, nor to a traditional Andean culture. In this way, Poole considers that their bodies and their image were inscribed in unique ways in European fantasies of power and possession (Poole, 1997: 126).

Some parallels can be found between the cholas of Bolivia and the mengalas of Guatemala, as economically autonomous and racially ambiguous women. Women like the mengalas, merchants who occupied public spaces, contradicted the idea of delicate and morally responsible women promoted in print media. On the other hand, by not fitting the stereotypes of indigenous women, for the intellectual elites the mengalas represented a contradiction of their polarized view of society. It is possible that, given this identity ambiguity, the circulation of their representations in print media was limited.

Another representative case of the circulation of photographic images in printed works is that of photographer and printer José Domingo Laso, from Quito, Ecuador. The photographer made portraits of white families, as well as postcards with genre scenes and popular types. In the urban views, the photographer literally erased or "dressed" as women the indigenous people who incidentally appeared in his shots, with voluminous and Frenchified dresses. For François Xavier Laso, this practice of concealment was part of the construction of the Ecuadorian nation and of hygienic and modern photography, an ideology shared by the photographer (Laso, 2015: 114).

As Poole explains, portrait photography of the working classes, peasants and indigenous people shows that far from being pigeonholed by racialization processes and typologies, users resisted and appropriated it. In the same way, the indigenous families of Quetzaltenango used photography to justify their role in the model of the nation, while vindicating their identity and giving themselves the right to self-represent themselves (Grandin, 2004: 143). However, in the print media of Guatemala's urban elites, the flow of those portraits that deserved to be exposed to wider audiences in order to project an idea of nationhood was controlled.

Conclusions

In a multiethnic country like Guatemala, the absence of indigenous women in the pages of the press and publications is striking. While it is true that images of "Indian types" were published, they were either folkloric in nature or intended to show them as a potential labor force. The selection of portraits, on the other hand, was intended to exhibit an ideal of Guatemalan beauty essentially ladinized and visually bleached, so that it would be attractive to the male eye, mainly Western. This trend is not confined to Guatemala alone, as was seen in the example of the "Peruvian Beauties". However, it does mark an important distance from the case of Mexico with respect to the meaning given to the "Indias Bonitas". The Mexican "Indias Bonitas" were those young indigenous women attractive to Mexican men as the genesis of mestizaje. In Guatemala, on the other hand, the "Indias Bonitas" are young ladino women disguised as indigenous women, who do not pretend to assume an indigenous identity or pay homage to them as national symbols, but are framed only within the Marian celebration.

Thus, it can be said that there was a tendency to make indigenous women invisible as part of the national identity, at least within the visual narratives of the press and print industry, in order to show a Guatemala in the process of ladinization. In the same sense responds the absence of other fluid identities such as the mengalas, who break with the Indian-Ladino binomial of the liberal model and, moreover, show the failure of the ladinization project.

Bibliography

Aguayo, Fernando y Julieta Martínez (2012). “Lineamientos para la descripción de fotografías”, en Fernando Aguayo y Lourdes Roca (coords.). Investigación con imágenes. Usos y retos metodológicos. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora,pp. 191-228.

Burke, Peter (2005). Visto y no visto. El uso de la imagen como documento histórico. Barcelona: Crítica.

Chajón Flores, Aníbal (2007). El traje de mengala, muestra de la cultura mestiza guatemalteca. Ciudad de Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

Carneiro de Carvalho, Vania y Solange Ferraz de Lima (2005). “Individuo, género y ornamento en los retratos fotográficos, 1870-1920”, en Fernando Aguayo y Lourdes Roca (coords.). Imágenes e investigación social. Ciudad de México: Instituto Mora.

Carreño, Manuel A. (1853). Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras para uso de la juventud de ambos sexos en el cual se encuentran las principales reglas de civilidad y etiqueta que deben observarse en las diversas situaciones sociales (Pedro Roque, ed.), versión digital, p. 84. Recuperado de: https://www.academia.edu/7225128/manual_de_carre%C3%91O

Casaús Arzú, Marta E. (1999). “Los proyectos de integración social del indio y el imaginario nacional de las élites intelectuales guatemaltecas, siglos xix and xx”, Revista de Indias, vol. lix, núm. 217, pp. 775-813.

Dubois, Philippe (1986). El acto fotográfico. De la representación a la recepción. Barcelona: Paidós.

Escobar, José Luis (2017). “Mengalas, el vestido antaño de las mestizas”, Prensa Libre. Periódico líder de Guatemala, sección Revista D, 16 de julio, versión digital. Recuperado de: https://www.prensalibre.com/revista-d/mengalas-el-vestido-antao-de-las-mestizas/, consultado el 01 de junio de 2022.

Ericastilla Samayoa, Ana Carla (1997). “La imagen de la mujer a través de la criminalidad femenina en la Ciudad de Guatemala (1880-1889)”. Tesis de licenciatura. Ciudad de Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos.

Grandin, Greg (2004). “Can the Subaltern be Seen? Photography and the Affects of Nationalism”, Hispanic American Historical Review, 84:1, Duke University Press.

Laso Chenut, François Xavier (2015). “La huella invertida: antropologías del tiempo, la mirada y la memoria. La fotografía de José Domingo Laso. 1870-1927”. Tesis de maestría. Quito: flacso Ecuador.

Muñiz, Elsa (2002). Cuerpo, representación y poder. México en los albores de la reconstrucción nacional, 1920-1934. Ciudad de México: uam.

Navarrete, José Antonio (2017). Fotografiando en América Latina. Ensayos de crítica histórica. Montevideo: Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo.

Onfray, Stéphany (2016). “La imagen de la mujer a través de la fotografía en el Madrid decimonónico: el ejemplo de la colección Castellano de la Biblioteca Nacional de España”, en Abel Lobato Fernández et al. El legado hispánico. Manifestaciones culturales y sus protagonistas, vol. 1. León: Universidad de León.

Ortiz Gaitán, Julieta (2003). Imágenes del deseo. Arte y publicidad en la prensa ilustrada mexicana (1894-1939). Ciudad de México: unam.

Pezzat Sánchez, Paulina (2021). “Los retratos del ‘bello sexo’. Una aproximación interseccional a los retratos de estudio femeninos en Guatemala, 1900-1950”, Istmo. Revista virtual de estudios literarios y culturales centroamericanos, núm. 43, pp. 29-48.

Picaudé, Valérie (2001). “Clasificar la fotografía, con Perec, Aristóteles, Searle y algunos otros”, en Valérie Picaudé y Philippe Arbäizar (eds.). La confusión de los géneros en fotografía. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

Poole, Deborah (1997). Vision, Race, and Modernity. A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

— (1999). “Raza y retrato hacia una antropología de la fotografía”, Cuicuilco, vol. 6, núm. 16, mayo-agosto.

— (2004). “An Image of our Indian”: Type Photographs and Racial Sentiments in Oaxaca. 1920-1940”, Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 84, núm. 1, pp. 37-82.

Reina, Rubén (1959). “Continuidad de la cultura indígena en una comunidad guatemalteca”, en Jorge Luis Arriola (ed.). Cuadernos del Seminario de Integración Social Guatemalteca, núm. 4.

Rodríguez Morales, Zeyda (2012) “La imagen de las mujeres en postales de la primera mitad del siglo xx en México y su relación con la identidad y la afectividad”, en Sara Corona Berkin (coord.). Pura imagen. Métodos de análisis visual. Ciudad de México: conaculta, pp. 225-264.

Schaeffer, Jean-Marie (2004). “La fotografía entre visión e imagen”, en Valérie Picaudé y Philippe Arbaïzar (eds.). La confusión en los géneros en fotografía. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

Scheer, Monique (2012). “Are Emotions a Kind of Practice (And is That What Makes Them Have a History)? A Bourdieuian Approach to Understanding Emotion”, History and Theory, 51. Wesleyan University, mayo, pp. 193-220.

Taracena Arriola, Arturo (2002). “Guatemala: del mestizaje a la ladinización. 1524-1964”. Austin: Texas Scholars Works, Universidad de Texas, pp. 1-24.

— (2005). “La fotografía en Guatemala como documento social: de sus orígenes a la década de 1920”, en Imágenes de Guatemala. 57 fotógrafos de la Fototeca de cirma y la comunidad fotográfica guatemalteca. Antigua Guatemala: cirma.

— (2008). Guadalupanismo en Guatemala. Culto mariano y subalternidad étnica. Mérida: unam/cephics.

Valdez Marín, Juan Carlos (2014). Conservación de fotografía histórica y contemporánea. Fundamentos y procedimientos. Ciudad de México: inah.

Zavala, Adriana (2006). “De santa a india bonita. Género, raza y modernidad en la ciudad de México, 1921”, en María Teresa Fernández Aceves, Carmen Ramos Escandón, Susie Porter (coords.). Orden social e identidad de género. México, siglos xix and xx. Ciudad de México: ciesas/udg.

Fuentes y Archivos

La Locomotora. Revista de Política, Ciencias, Literatura, Bellas Artes (1907). Hemeroteca Nacional de Guatemala.

El Libro azul de Guatemala (1915). Latin American Publicity Bureau Inc. Academia de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala.

El Imparcial. Diario Independiente (1924). Hemeroteca Nacional de Guatemala.

El Imparcial. Diario Independiente (1926). Hemeroteca Nacional de Guatemala.

Lecciones de geografía de Centro América, por F. L., Librería y Papelería de Antonio Partegas, s/f. Academia de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala.

Paulina Pezzat Sánchez holds a B.A. in History from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. D. in History from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ciesas Peninsular headquarters, where she has developed studies of the image in Oaxaca and Guatemala with an intersectional approach. She has emphasized the revaluation of photographic images as sources for history and historiographic dialogues in Latin America.