Scientific dissemination as science, technique and art. The case of "musicaenelnoreste.mx".

- José Juan Olvera Gudiño

- ― see biodata

Scientific dissemination as science, technique and art. The case of "musicaenelnoreste.mx".

Receipt: May 31, 2023

Acceptance: September 22, 2023

Abstract

This article describes the challenges we faced in building a social science outreach website specializing in popular music studies in northeastern Mexico and south Texas. It makes explicit the problems related to the models of social science communication that we have encountered. These challenges include communication and negotiation processes with those who collaborated in the construction of scientific knowledge and now do so in its dissemination stage, to which are added publicists or technicians in social communication. All of them always have similar and/or alternative visions to ours. The complexity of the dissemination work is highlighted and the notion that identifies it as a dispensable complement to the construction of scientific knowledge is combated.

Keywords: diffusion, popularization of science, communication models, popular music, northeastern Mexico

science outreach as science, technique and art: the case of musicaenelnoreste.mx

This article explores the challenges of developing a website for outreach in the social sciences, specifically one specializing in popular music studies in Northeast Mexico and South Texas. It touches on the communication models of the social sciences, including the communications and negotiations with those who developed the scientific knowledge and are now involved in the stage of outreach as well as publicists or social communication experts. The visions of these individuals do not always coincide with those of the website developers. While emphasizing the complexities of outreach, the article challenges the idea that it is imperative for the building of scientific knowledge.

Keywords: scientific outreach, dissemination, communication models, popular music, Mexican northeast.

Introduction

This article describes the challenges we faced in building an electronic social science outreach site specializing in popular music studies called www.musicaenelnoreste.mx. The site was developed to share with the general public ethnographic material, written and audiovisual, about three musical cultures of northeastern Mexico and south Texas. Throughout the text I identify methodological and technical challenges related to the dissemination of social scientists' products and ways of working. I make explicit epistemological problems related to models of social science communication that we have encountered since 2018, when construction of the site began. These challenges include definition of objectives, communication and negotiation with artists, cultural promoters and researchers, who collaborated in the construction of scientific knowledge and now do so in this stage of dissemination. Publicists and designers or social communication technicians were added to these actors.1 All of them have similar and/or alternative views to ours. The complexity of the dissemination work is highlighted and the notion that identifies it as a colophon or dispensable complement to the construction of scientific knowledge is combated.

I identify this particular website as a science outreach product that is part of the activity of public communication of science and technology. I understand the nature of my academic work as an effort to understand social processes through various means, in particular through ethnographic work. Learning from people, their cultures and contexts entails giving back in different ways, both at the time of obtaining data and at the end of the research, by delivering to all the academic and other subsidiary products. For this dissemination process, the same was done: explaining the project and asking for and receiving help, always being open to proposals from those who have and practice knowledge. In this sense, this article can be understood as an ethnography on the conceptualization and interaction between academics, musicians, promoters and technicians, necessary for scientific dissemination, as well as on the problem of the communicative model and its specificity when dealing with sounds, images and texts.

Finally, one of the lessons learned in the process of building this web page, which I propose as the thesis of this article, is that we academics are knowledgeable subjects of the conditions of mode and place of the transit of scientific knowledge, but only among ourselves. We have the skills to build a series of goals or objectives, specify the type of audience and calculate the type of impact for our dissemination work, but we are not so well prepared to do so in our outreach work. I am referring to a culture of training, planning, administration, financing and constant evaluation.

After offering a clarification of concepts such as outreach, science communication, dissemination and popularization, our experience will be described in three dimensions: the research project, the process of dissemination of such a project and, finally, the discussion of the challenges and difficulties that this effort entailed.2

Conceptual clarification

We start from a polysemic reality within the academic world, where the concepts of science and technology communication are sometimes used differently and sometimes synonymously (cpct), popularization, dissemination and popularization of science, which sometimes does not help to deepen the debates (Escobar-Ortiz and Rincón Álvarez, 2019). Generally, all these refer to the act of communicating results or findings of scientific advances in their different dimensions, to diverse audiences. This section works on a conceptual clarification of these and other related terms.

According to Luis Estrada (2014: 3), the concepts of. diffusion more oriented towards communication with other groups that do science; the disclosure would be aimed at broad audiences, without specialized knowledge, while science communication would be a dialogue, an interlocution, making communication an "active" action.

In their critique of the deficit and democratic models of science communication, Escobar-Ortiz and Rincón-Álvarez (2019) state that the former is based on a simplistic view of both science and audiences, and the latter is based on the recognition of multiple knowledge and the need to establish a dialogue between scientists and non-scientists. Thus, they are not in fact antithetical models, i.e., there are situations that may have elements of both. They propose another model based on the recognition of the circumstances of mode and place in which a knowledge transits from one context to another. Hence, when scientists assume a mode and place, a context, where their work is to talk among experts, a unidirectional character arises. But it can also happen that multiple contexts are located and possible dialogues between different interlocutors are recognized. "In this case, the communicative process occurs in a multidirectional way, from the public to the experts, from the experts to the public, from the public to the public, among other options, always depending on the places where science and technology are produced" (Escobar-Ortiz and Rincón-Álvarez, 2019: 144).

In the case of Mexico, in the Manual for filling out the Single Curriculum Vitae (conacyt, 2018), which is the platform of the conacyt3 where the activities and products of academics, including those who belong or want to belong to the National System of Researchers, are registered, the particularities of the public communication of science and technology (cpct). First, the definition of Manuel Calvo in Sarelly Martínez (2011) is taken up: "dissemination of information on science and technology that includes the media and their instruments of diffusion", and the clarification of Cazaux (2008: 8) is added, that the cpct "covers all communication activities with scientific content through techniques such as advertising, entertainment, journalism and others, but excludes communication between specialists for teaching or research purposes".

On the other hand, the concepts of scientific culture and social appropriation of science. Leonardo Silvio (2009: 110) locates two senses of scientific culture: one related to a public perception that combines understanding of scientific facts and attitudes towards science and technology. The other, broader, refers to exchanges of meanings The main objective of the project is to develop a new approach to science and technology -explicit or latent-, by different social actors and groups. This constant tension and negotiation between different meanings accompanies, to a greater or lesser extent, the very development of science and technology and what has been called the social appropriation of technology. Such a dialogue can lead to a more horizontal relationship and promote different social appropriations of science, since "a conception that immerses the institution and activity [of Science and Technology] in the dynamics and tensions of society [...] will focus the legitimacy of scientific knowledge on other values and interests, in addition to those of science (Silvio, 2009: 98). Therefore, León Olivé (2011: 114) distinguishes two types of appropriation: a weak one, which consists of the incorporation of scientific representations in the culture of the public, and a strong one, which also includes diverse practices in people's lives, practices guided by these scientific and technological representations, and which may include what Olivé calls innovation social networks (underlined), where those affected by a problem and experts participate, "in which problems are constituted, existing knowledge is appropriated, new knowledge is generated, solutions are proposed for the problem in question and actions are taken to achieve them" (Olivé, 2011: 114).

From my experience I consider that, in some areas of the social sciences and humanities, the questions of disseminating for whom, based on what assumptions, with what objectives, etc., are also linked to the conditions of the research project itself. In other words, what is situated is not only the dissemination or communication, but the researcher and the whole process of generating and disseminating knowledge. To follow Leyva and Shannon (2008), I would use as an example a work that they and other authors call co-labor,4 where decolonized research leads social scientists and peasant leaders to agree on common goals for scientific work and discussion of results. This can lead, from the planning of the research, to the commitment of locating a phase of discussion of the results of both, not only in academic spaces but also in the peasant communities. Thus, the unidirectionality or multidirectionality of scientific dissemination would be conditioned from the beginning of the research process.

We can summarize up to this point by saying that there is communication between scientists, generally called "dissemination", and that other communications between scientists and other audiences can be called "outreach" and refer to one-way information, or to different types of dialogues between scientists and other actors or social communities. When science popularization is developed in many ways (at school, at home, in the company), the social appropriation of science increases, particularly if one participates in some way in its construction, debate or critique.

The polysemy of concepts mentioned here is also linked to the evolution of science itself in its ontological, epistemological, methodological and ethical dimensions, as well as to the evolution of society itself, of its power relations and of its own practical use, which does not always follow the advances in the reflections of academics, nor the changes in politics.

Thus, following a global trend that takes advantage of the benefits of digitization, Colombia, Argentina and Mexico highlight in their science and technology legislation the theme of "open science", to which different types of audiences should have access (minciencias, 2019: 3; conahcyt, 2023; sncti, 2013:1). In the case of Mexico, the new law of the conahcyt (2022) emphasizes the notions of "popularization of science", "universal access to knowledge" and "right to scientific information".

As part of the obligations assumed by the State, now "any person receiving public resources for [science] shall have the obligation to make publicly available the information derived from them, including the databases they generate, if any" (Article 60: 18). Likewise, the State is obliged to establish and maintain spaces for the dissemination of the humanities and sciences, as well as to update the information published (Article 56: 16) and, finally, through public research centers, to finance the professional updating of researchers and technicians to improve their competencies in terms of dissemination (conahcyt, 2023).

Colombia, for its part, highlights the shift from the notion of "appropriation of science", in its 1990 Science and Technology Law (Ministry of Labor, 1990: 15), to that of "social appropriation of knowledge" in its new regulations, incorporating the concept of "other knowledge" into recognized science. A recent document, its national science policy for the decade 2022-2031, indicates as one of its seven strategic axes "Increasing the social appropriation of knowledge" (conpes, 2021: 3). In another public policy document of the Ministry of Science of that country, it is defined as the one that

...that is generated through the management, production and application of science, technology and innovation, is a process that summons citizens to dialogue and exchange their knowledge, know-how and experiences, promoting environments of trust, equity and inclusion to transform their realities and generate social wellbeing (minciencias: 2021: 6).

Thus, one of the relevant actors in this tension, dialogue and negotiation is the State and the actors that dispute power. Therefore, science communication, popularization, popularization, scientific culture and appropriation also evolve in response to possible ideological and public policy changes of governments, which take up some concepts and set aside others.

The research project

The project "Process of Culture Production in Northeast Mexico and South Texas. The cases of hip hop and norteño music" was funded by the conacyt. Its objective was to "Generate information and analyze the contemporary processes of production and circulation of northern and hiphop music cultures,5 in northeastern Mexico and south Texas, with the potential to fuel sustainable economic and social policies linked to culture".6 Its specific objectives were: a) To detect problems for the development of local cultural industries linked to the specified genres; b) To highlight the articulation between musical production-distribution processes, regional social space and social class of the actors, individual or collective, c) To identify current projects in the vulnerable youth population oriented to music, with high impact on the forms of social cohesion and the management of musical knowledge; d) To identify the role of human mobilities and mass media in the expansion and evolution of these musical cultures.

The research incorporated the work of sixteen researchers and scholarship students throughout its four official years of life. This allowed the creation of a research group oriented to socioanthropological studies of popular music in the northeastern region and opened a line of research that is being developed at the ciesas-Northeast, through a variety of scientific dissemination and outreach activities. The team was able to generate 120 academic products and activities. Regarding the former, it managed to publish two books and a thematic dossier in a research journal, eight articles and six book chapters, all peer-reviewed, in addition to five bachelor's and master's theses. Regarding the latter, two international colloquia and a monthly seminar were held between 2015 and 2018.

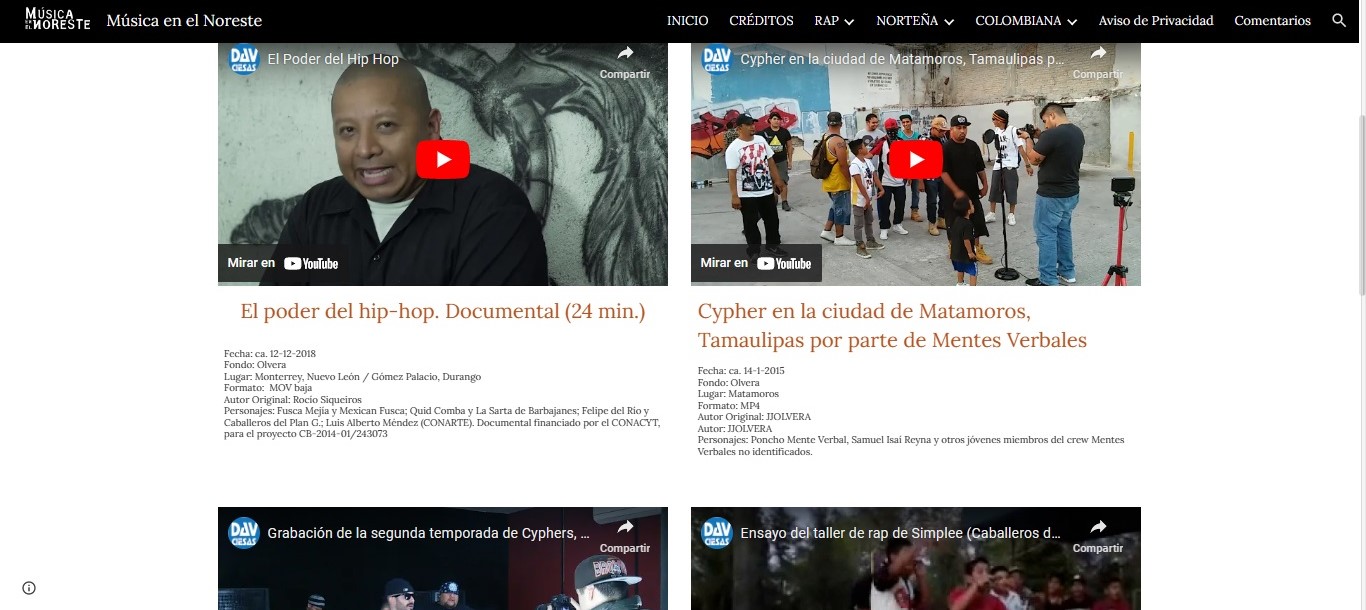

Finally, daily outreach activities were carried out for a wide audience, such as workshops, talks and interviews in various media, including a documentary video (financed by the conacyt) and a website, which is the subject of this article.

The peculiarity of this project is that, although they share objectives, they were actually two different investigations (Norteño music and rap music), with different actors and contexts. Once the dissemination tasks were advanced and the potential of the web site was observed, it was decided to incorporate material from a previous research on the so-called Colombian music of Monterrey. This will be important to explain the differentiated constructions within the web page.

The dissemination project

The fundamental motivation of this effort has been to go beyond the academic spheres in which the knowledge generated is distributed. Its origin lies in personal experiences in the construction of large bodies of empirical material for social research. Through close acquaintance or direct participation in their elaboration, these experiences had left me both excited and disappointed at the same time.8 Originally intended to provide empirical evidence for different individual projects of researchers and, at the same time, to leave a basis for future work by thesis students and other researchers, these large databases ended up archived in the computers of their creators or in electronic sites that, since they were not renewed, left the information out of the reach of possible interested parties. Ontologically, I wondered whether the only knowledge generated was that which was published and whether other knowledge could be generated from unpublished knowledge, with a different nature and purpose.

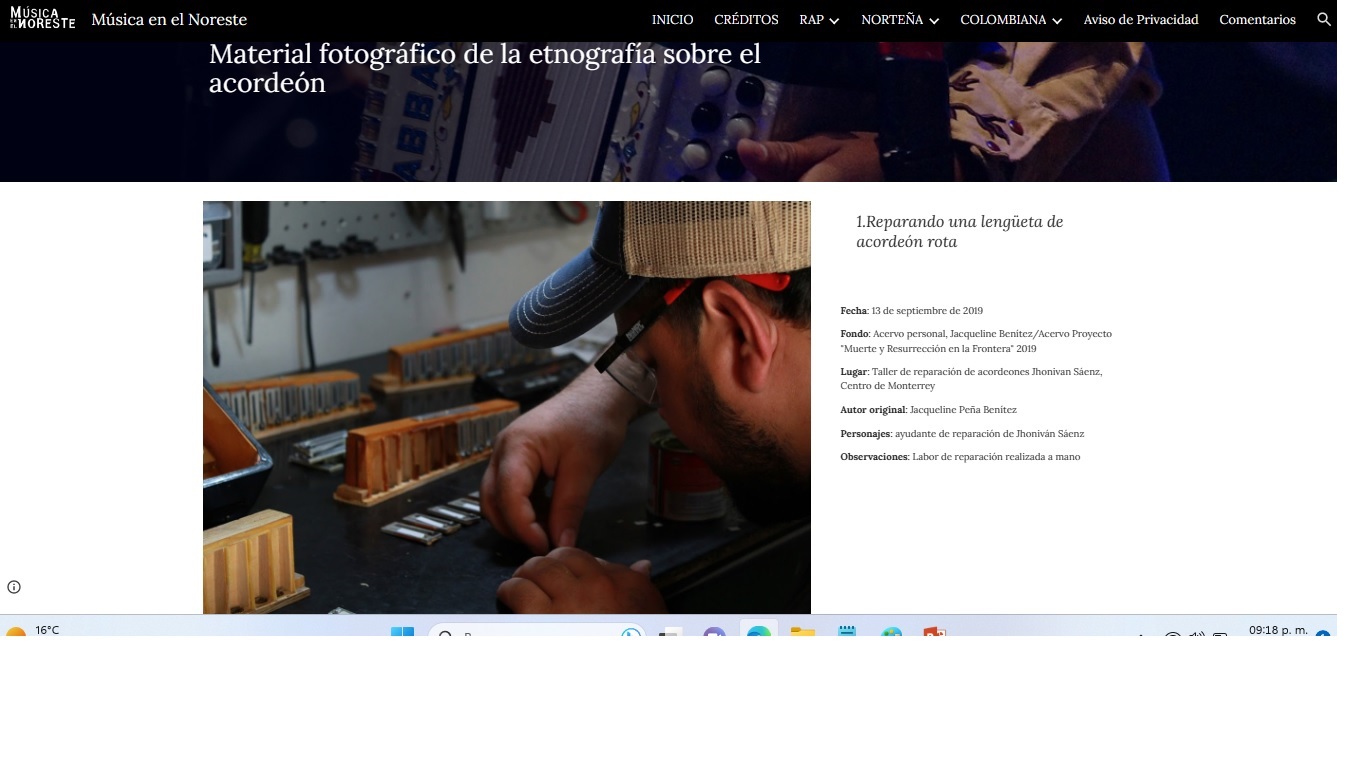

Therefore, my project sought to achieve two central objectives: to make available to the public at large and on a permanent basis, both academic and outreach material that would otherwise be left in our digital drawers. In fact, much of this material was provided by the actors-collaborators themselves, so that, when we speak of making the material available, we speak of "returning it" and expanding the number of interlocutors. Methodologically, therefore, we should look for less rigid formats to circulate knowledge. The second objective has been to bring people closer to the work we do as researchers; in particular, to give them details of how ethnographic work is done.

Although it was not a process of co-laborIt is important to clarify that I had two groups of specialists (artists, cultural managers, researchers) who followed up on the work. In addition, I was fortunate to work the first two stages with an assistant historian-rapper: Fusca Mejía. I was his director of two theses (bachelor's and master's). The joint learning that always takes place in these processes deepened when he became my assistant and later a colleague.

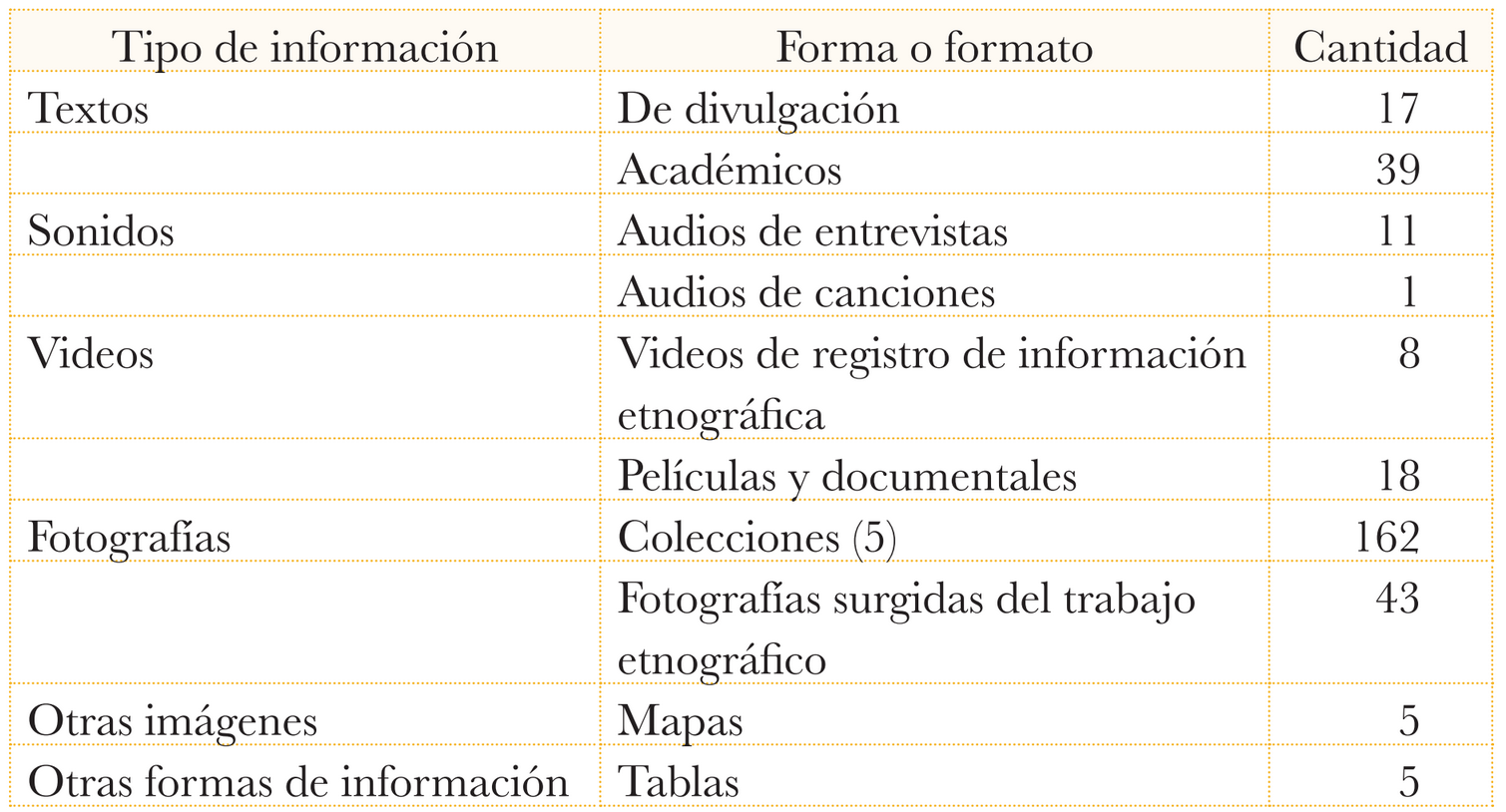

The dissemination project, which is based on a democratic model of scientific communication and, to a certain extent, on a multidirectional perspective, has the following stages: 1) planning, 2) rap music, 3) norteño music, 4) Colombian music. In this article I concentrate on the first three stages, which are either completed or well advanced. I must emphasize that, just as the first two are distinct investigations, with different actors and contexts, inserted in a single project, so too was the process of assembling the dissemination materials very different. Table 1 shows the products offered on the website.

First stage: site planning

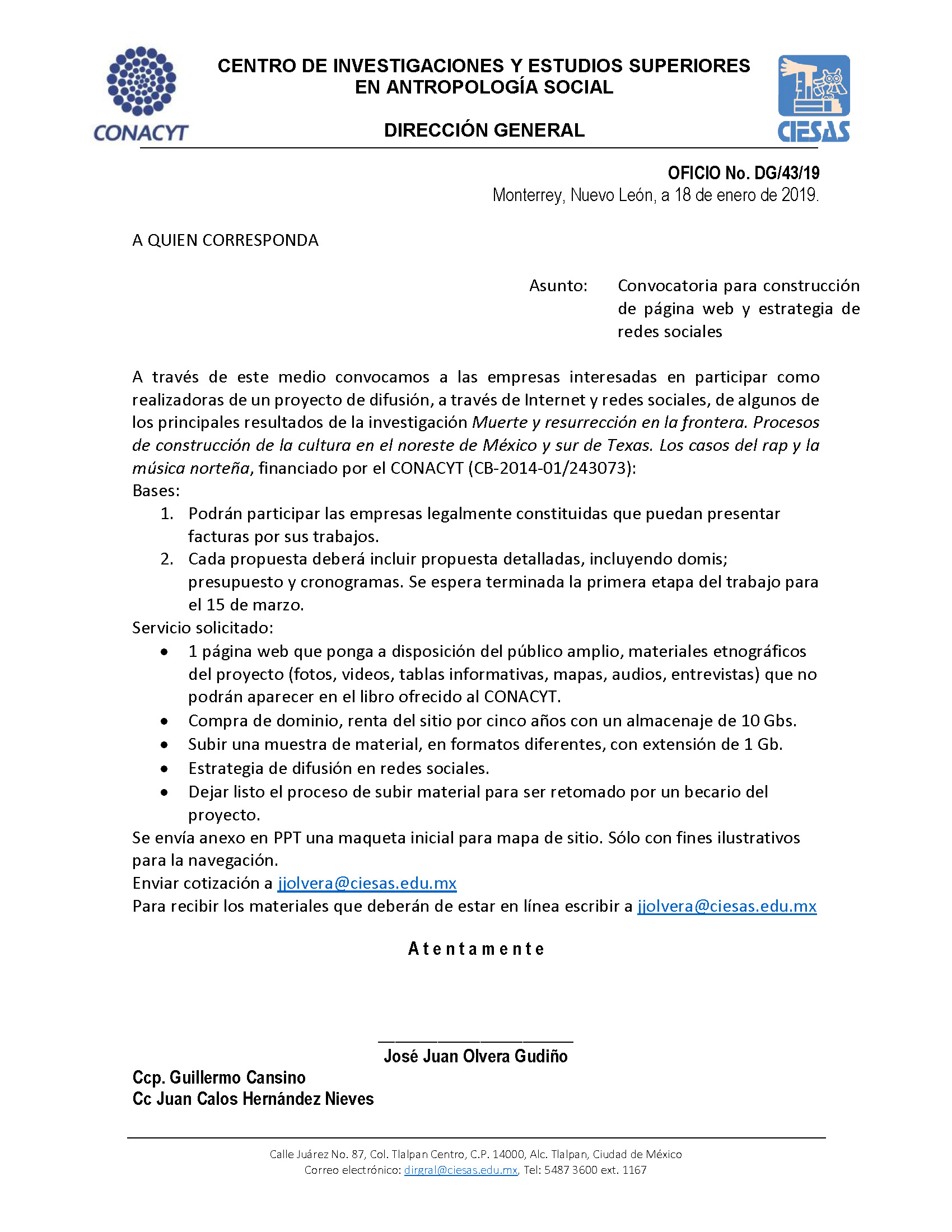

I started the planning in March 2018. I made a first sketch of the various pages and a request to the conacyt to redirect an amount of my research project for this website. I received approval in May of that year and resumed this project until March-April of the following year (2019).

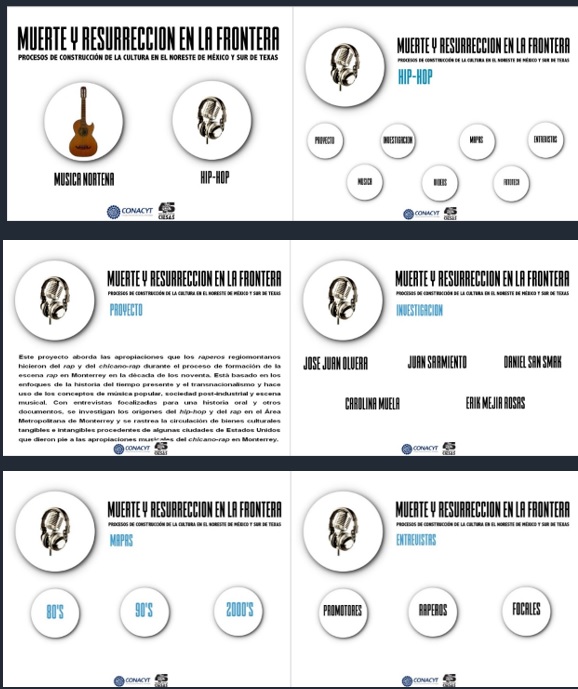

A call for tenders had to be made with a minimum of three companies offering the service. The first one, in January 2019, failed. A second one was made with enough competitors and there we showed them our first sketch, notified the approximate number of information to be uploaded, its different formats and clarified general doubts.

After having a winning company, the communication process followed to explain the detailed plan of the work and the final mission of this company; it was explained to those in charge of the service -who had both technical and artistic knowledge- the way we imagined it would work. Thus, the different problems of design, accessibility (possibility of use), usability (linked to the quality and effectiveness of use) and navigability (possibility of traveling between all the pages of the site comfortably and without getting lost) were worked on, according to the types of audiences imagined (Duque et al., 2015: 140). It was necessary to develop an art that had not been worked on in previous experiences: to talk with an open mind and reach agreements with other creatives amid empathy and differences, but also the recognition of our client-supplier relationship. The fact that the suppliers understood what we wanted and were open to our concerns generated an atmosphere of trust, even if it took longer than expected.

After several months of work, we finally finished a technical-artistic proposal that developed the previous points, but also a series of alternatives about the platforms where the project could be set up and the information could be stored. It was decided to use Google's platforms (Sites, Drive and Gmail) and to rent a hosting service from a company dedicated to it. Important planning challenges arise here, starting from recognizing the differentiated nature of traditional electronic sites and social networking platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, etc. As an electronic site, one can buy a name, which constitutes a space or "land on the web", for which one pays; in addition, one must find a place to store the information, storage for which one also pays. The content of a web page is the property of the uploader, while social media platforms have rights over the content uploaded. Experts differentiate in structure and content the traditional website and the social network, "(the one) where the 'social' or 'experience' web predominates" (Evans, 2011: 5). Generally, a traditional website is used to share (relatively homogeneous) content for diverse audiences. These can be found through search engines, such as Google, Yahoo or Bing, while the evolution of the web allows social networks to build communities that share content and communication, with an emphasis on instantaneity. Traditional electronic sites also have feedback systems, but they are poorer and slower. Hence, what is recommended is a balance and complementarity when using one or the other.

We knew about the "relative immobility" of web pages with respect to the dynamism of social networks; that electronic sites are rarely visited and social networks are in vogue in a fluid environment in which much of today's culture moves. But, by the same token, we were aware of the relative inaccessibility of their materials, since finding specific information from two years ago on Facebook, for example, is extremely cumbersome. Thus, there is a certain inability for some materials to remain, due to the fleetingness with which some contents are superimposed on others. We agreed with the designers to build us then the electronic site but connected with some social networks.

Their proposal was that the "Music in the Northeast" site would have a main connection with a Facebook page, called the same way, in which new contents would be announced every time they were ready on the website. But the designers' idea was broader and more ambitious. So they made us Gmail, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Soundcloud accounts. It is true that, with good planning and other activities, digital social networks make it easy to publish content through their own tools. But even so, the number of social networks included in this first proposal far exceeded our operational capacity to upload and update material, as well as to pay attention to possible feedback from the public. If we did not do something soon, the dynamics would end up preventing us from even finishing the main project, which was the web page. So we asked them to cancel them and we didn't work on them anymore.

Second stage: rap music section

This stage was carried out in a more or less planned manner. A calendar was made to schedule the incorporation of new materials to the page and announce it through social networks to feed traffic to the page. These included brief descriptive messages about the new content, we added some sample images and posted the address of the page. The messages had their respective hashtagswhich are marks used to identify topics of posts, which the user can then search for in that way. The @ symbol is used to mention another user or "friend" on a social networking site. The expected audiences were young people in general and, in particular, followers of this type of music; to a lesser extent, academics and other audiences.

Rap musicians, promoters and other hip hop culture experts, with whom we worked during our research project, were convened for this process. They were asked to help us review the contents and make suggestions. Initially, there was an invitation for them to take over the site at the end of the entire project, but the idea faded as the project lengthened, other musics were integrated and other actors began to intervene. The pandemic ended up pushing the idea away.

We must insist that the level of participation allows us to speak of a review, participation, validation of the effort of the actors, but not of a co-labor with all of them, both in the sense of research and in the sense of the practical products that are produced from the knowledge generated (Leyva and Speed, 2008). While it is true that these colleagues had shown empathy with our interest in researching and disseminating their musical culture, it did not go beyond that, from review and support. So we cannot say that this is a project elaborated by them, except in the case of rapper Fusca Mejía, mentioned above. With him we can say that there was a work of co-labor, both as a rapper and as a historian and anthropologist. Finally, talking to artists about a dissemination project that speaks of them and has an artistic dimension is also an art. These are people with special sensibilities, with competencies and rivalries in different spheres.

At this point I had already made a strategic mistake. I allowed the linkage between the website and a new Facebook page, when I already had another one called Music Studies in the Northeast. It was born in 2014 as a project to disseminate all our academic and outreach activities among other academics, but also among artists and promoters. This duplicity complicated the project, because while we were feeding the new Facebook page informing about new additions to the website (photo backgrounds, recently uploaded interviews), it let the other one die. By the time I realized the mistake, there was no way to fix it without a cost. One of the lessons I learned from this exercise was the need for more planning and an attitude of foresight that would not let me get carried away by the ambition of wanting to eat up a digital world that I knew little about.

On the other hand, we had to solve the copyright issue: obtaining permission to upload the material that the owners or authors originally offered us for our research and that sometimes appeared in our academic products. This was and is a delicate and difficult situation for several reasons. We had to locate them and then explain to them the new use of the material. It was good news for everyone because it contributed to the intention of dissemination and, although the cause was the same (to disseminate a musical culture, its exponents, its difficulties to survive from music, etc.), the container -the electronic page- was new. In addition, many materials did not appear in the academic products and we did not have signed permissions from them. So they didn't always understand why they were being asked for a new signature or a signature for the first time. On the other hand, this is an important document more than anything else for the author or owner of the material to be disseminated, but many of them were not aware of these procedures. The culture of trust over the culture of formal legality made some collaborators who offered interviews, photos or audios prefer to give us their oral permission and avoid signing something that they do not write or control, or simply did not want to read. In some cases they had signed permissions for the book's publications, but locating them again for another permission was very difficult.

In addition to this, a special page was established for our privacy notice stating that this is a non-profit project; that permission has been requested from the owners of the materials to use them only for this purpose, and that it complies with the provisions of the Personal Data Law. It also establishes the procedure for exercising the rights of access, rectification, cancellation and opposition (arch), instituted in Article 16 of the Mexican Constitution. https://www.musicaenelnoreste.mx/aviso-de-privacidad

Third stage: norteño music section

The third stage began in 2021 and has not yet been completed. The experience of the first stage was used for its elaboration. Since this part of the research project had more national and foreign thesis students and researchers, there was also more material to work with. However, much of this material in its academic format was just emerging or had just emerged. Thus, one of the characteristics of this period was to ask several colleagues for a new product: an excerpt of their work to be made available, not to academics, but to the broad public. Preferably, this product had to be audiovisual and would also have to be accompanied by an explanation for the public.

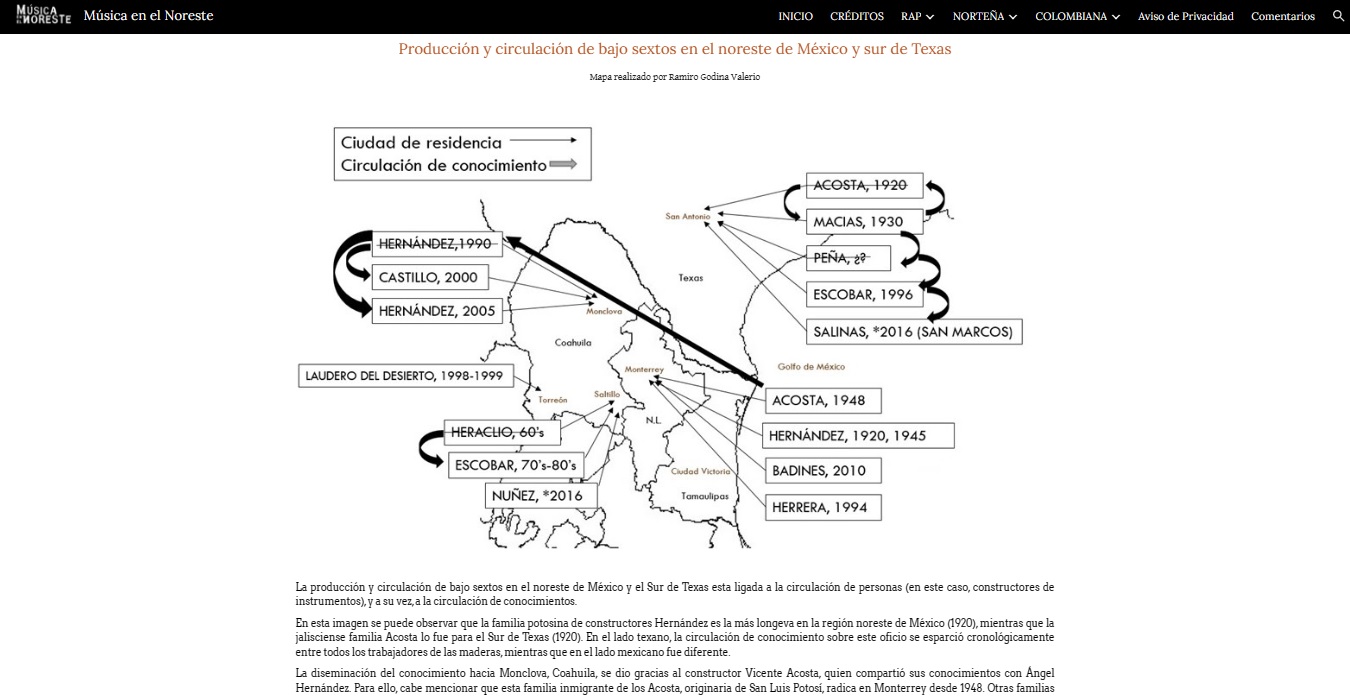

We have the example of the map of the circulation of knowledge in the families of lute makers in Mexico and the United States, which was worked on by Ramiro Godina Valerio (2022). It was a matter of passing the map of an academic book -Economies of scaleúsicas northern- to the website. A brief and simple wording should include what it is, why it was made and how such a map was made. The response to this request did not have the required alacrity, but in the end it was achieved.

Another example is the sound of the clock in the main church of Repueblo de Oriente, part of the municipality of Los Ramones, Nuevo León. This area has a historical migration to the United States and the bell, acquired by the migrants, has a special meaning for the inhabitants who remain, especially in the context of the deep silences in the times when the town is half empty. You can see the photo, sounds and explanation of this clock at this address: https://www.musicaenelnoreste.mx/nortena/entrevistas-y-audios/audios .

For the final design of this stage, a group was convened to review and make suggestions to the original design. They were three academics linked to the subject, the representative of a traditional music group from the northeast (Tayer) and a writer and researcher of corridos norteños. From their observations, which we are working on, we highlight one of them. The artist who made this remark said that she perceived in the website a very interesting dialogue between different artists and generations in the region; that she found it very educational and hoped that it would also be so for the rappers. This gave us the idea of incorporating the work on Colombian music, done two decades earlier, and which has nothing to do with the research project, but now has to do with the dissemination project. The fourth stage, related to Colombian music, just started in 2022 and has not concluded yet.

I end this section by indicating that, from the beginning of the second stage, a constant concern was to position this dissemination proposal through the most important search engines (Google, Bing, Yahoo). It is a matter of making efforts so that every time an interested user searches, with different combinations of words, for information about popular music in the northeastern region, the address of the site I built will appear.

This was important also because we were not always going to be able to feed traffic to the site through social networks. The registration process with Google (who holds 85-90% of the global market) was the most complex and took over 18 months to achieve.

Problems and challenges. By way of conclusion

To conclude, we offer some reflections on problems and challenges surrounding this effort that may be useful to other colleagues initiating similar tasks, in terms of a culture of digital dissemination.

This outreach effort has placed me in a position of humility in terms of the complexity, amount of energy, institutional, human and economic resources required, as well as the lack of preparation and training, with which one embarks on enterprises of this caliber. In this sense, the enormous capabilities of digital structures and platforms, which far exceed what is contained in a printed product, such as a book or magazine, sometimes make us lose sight of the real possibilities of giving attention to each of the pieces of information that we upload to the network. In other words, we scale the work beyond our possibilities.

Regarding design and architecture, we talk about a process of planning, of imagining the diversity of possible audiences to whom one wants to address the work, in order to offer a pleasant experience of knowledge. When we talk about web design we refer to the above, but also to the design of typographies, images, backgrounds, so it is also about an aesthetic experience. When a group of artists, promoters and academics were evaluating the northern music section, they commented that the black backgrounds that accompany the information are appropriate for young audiences and for some of their musical cultures such as rock, heavy metal, punk and rap. They asked what made us think that something "so sad", such as the color black, could accompany Norteño music. Thus a critical process of appropriation was shown that put our design proposals in check. It ended up being an internal negotiation and with the rest of the project builders to adapt the design, navigability, usability and accessibility to the type of public imagined.

Of course, it has offered satisfactions for me and for those who collaborated with me, because those who have known it, have valued it. But before that, there must be an external validation of contents and design. It will always be better to have another public, particularly if it is a public knowledgeable about the subject, validate the dissemination proposals. Gathering feedback on design, content and putting it into practice, and then showing it back to the reviewing audience, is one of the most nourishing processes, but also one of the most difficult to complete. The circle is usually cut short before the last stage. In such a sense, the project lasted almost as long as the research itself (2015-2020 vs. 2016-2020), but has continued to date, showing that dissemination can be extended for much longer.

This project requires constant technical and financial maintenance to ensure that it is seen, used and shared. It is not so different from a book that, kept in an important library, must have a specific location, where it enjoys a place with a special climate and someone trained to find it and offer it to the public. And although now it is not necessary to go to the library in person, the interlocution with the public is key. Build communication channels and keep them open. The comments section on each of the pages is an example. The quality of feedback is what gives life to a project that wants to communicate with its users.

Bibliography

Cazaux, Diana (2008). “La comunicación pública y la tecnología en la “sociedad del conocimiento”, Razón y Palabra, 65. Consultado el 11 de noviembre de 2023 http://www.razonypalabra.org.mx/N/n65/actual/dcasaux.html

conacyt (2018). Manual de usuario para la captura del cvu. https://dadip.unison.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Manual_CVU_2018.pdf

— (2023). Plataforma digital para el llenado del Currículum VitaeÚnico.

conahcyt (2023). Ley General en materia de Humanidades, Ciencias, Tecnologías e Innovación. México: Gobierno de México.

conpes (2021). Documento conpes 4069: Política de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (2022-2031). Gobierno de Colombia. Consultado en https://minciencias.gov.co/sites/default/files/upload/paginas/conpes_4069.pdf

Duque, Miguel, Ivón Rodríguez, Gloria Arcos y José Luis Castillo (2015). “Mejora de la navegación de sitios web educativos para personas daltónicas mediante la creación de patrones de accesibilidad y usabilidad web”, en Carmen Varela, Antonio Miñan y Luis Bengochea (coords.). Formación virtual inclusiva y de calidad para el siglo xxi. Granada: Universidad de Granada, pp.140-147.

Escobar-Ortiz, Jorge Manuel y Andrea Rincón Álvarez (2019). “La divulgación científica y sus modelos comunicativos: algunas reflexiones teóricas para la enseñanza de las ciencias”, Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, vol. 10, núm. 1, Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, enero-junio, pp. 135-154.

Estrada, Luis (2014). “La comunicación de la ciencia”, Revista Digital Universitaria [en línea]. 1 de marzo, vol. 15, núm. 3 [Consultada:]. Disponible en internet: <http://www.revista.unam.mx/vol.15/num3/art18/index.html>.

Evans, Dave (2011). Internet de las cosas. La próxima evolución de Internet está cambiando todo. Informe técnico, cisco.

Godina, Ramiro (2022). “Producción y circulación de bajo sextos en el noreste de México y sur de Texas”, en Música en el noreste. Sitio de divulgación científica. Consultado en https://www.musicaenelnoreste.mx/nortena/mapas-y-tablas

Leyva, Xóchitl y Shannon Speed (2008). “Hacia la investigación descolonizada: nuestra experiencia de co-labor”, en Xóchitl Leyva, Araceli Burguete y Shannon Speed (coords.), Gobernar (en) la diversidad: experiencias indígenas desde América Latina. Hacia la investigación de colabor. cdmx/Ecuador/Guatemala: ciesas-flacso, pp. 34-59.

Martínez Mendoza, Sarelly (2011). “La difusión y la divulgación de la ciencia en Chiapas”, Razón y Palabra, núm. 78, noviembre-enero.

minciencias (2019). Decreto 2226 de 5/12/2019. Por el cual se establece la estructura del Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación y se dictan otras disposiciones. Gobierno de Colombia. Consultado en https://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?id=30038589

minciencias (2021). Política Pública de Apropiación Social del Conocimiento en el marco de la CTeI. Bogotá: Gobierno de Colombia.

Ministerio del Trabajo (1990). Ley de Ciencia y Tecnología. Bogotá: Gobierno de Colombia, pp. 1-34.

Olivé, Leon (2011). “La apropiación social de la ciencia y la tecnología”, en Tania Pérez Bustos y Marcela Lozano Borda (eds.). Ciencia, tecnología y democracia: reflexiones en torno a la apropiación social del conocimiento. Medellín: colciencias, Universidad eafit, pp. 113-121.

Olvera, José Juan (2004). “Bases de información sobre El habla de Monterrey. Proceso de construcción de un sitio de difusión sociolingüística”, en Lidia Rodríguez-Alfano (editora), El habla de Monterrey llega a la web. Trayectoria de una investigación sociolingüística. Monterrey: uanl-Trillas.

Olvera, José Juan (2020). Música en el noreste. Sitio electrónico. http://www.musicaenelnoreste.mx

Rodríguez-Alfano, Lidia (2004). El habla de Monterrey llega a la web. Trayectoria de una investigación sociolingüística. Monterrey: uanl-Trillas.

Silvio Vaccarezza, Leonardo (2009). “Estudios de cultura científica en América Latina”, Redes, vol. 15, núm. 30, diciembre, pp. 75-103.

sncti (2013) Ley 26.899. Repositorios digitales institucionales de acceso abierto. Buenos Aires: Gobierno argentino. Consultado de https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/ley-26899-223459/texto

Juan José Olvera is a sociologist, Master in Communication, PhD in Communication and Cultural Studies. He has ten years of experience in journalism. He has specialized in the sociology of culture, particularly in the socioanthropology of popular music. He is a member of the National System of Researchers, level 1. His latest research project has been "Regional processes of construction of culture in northeastern Mexico and south Texas: the cases of rap and norteño music". His latest publications are Economies of northern music (coordinator), Economies of rap in northeastern Mexico and Undertakings and resistances around popular musicboth of them published by Casa Chata, Mexico. His current research addresses the economic articulation between popular music and popular fairs.