Venezuelans in Costa Rica: between transit and settlement. The ethno-survey of recent immigration as a methodological contribution to the study of migration in countries of arrival.

- Jéssica Nájera

- ― see biodata

Venezuelans in Costa Rica: between transit and settlement. The ethno-survey of recent immigration as a methodological contribution to the study of migration in countries of arrival.

Receipt: January 15, 2025

Acceptance: January 20, 2025

Professor-researcher at the Center for Demographic, Urban and Environmental Studies of El Colegio de México, since 2015; BA in Economics, MA in Demography and PhD in Population Studies. Member of the sni and research networks on migration, family and work, and support groups for migrants. Her research focuses on the links between migration and work from a sociodemographic perspective, with quantitative and qualitative methodologies. She develops particular topics such as cross-border mobilities and migrations between Mexico and Guatemala; international migrations in Latin America, particularly in the Mesoamerican region; migratory flows and integration of migrants in Mexico; family, work and gender. She was responsible for the Survey on Migration in the Southern Border of Mexico (Emif Sur) from 2005 to 2008; and since 2019 she is a member of the Project on Mexican/Mesoamerican Migration (mmp) and Latin America (lamp-enir), projects of El Colegio de México and Brown University.

Abstract

In recent years, Venezuelan migration to many Latin American countries has turned some cities in the region into places of transit and migratory stay. The objective of this article is to show the methodological and empirical contribution of the Ethno-survey on recent immigration in Latin American host contexts (lamp-enir 2021), focused on understanding the living conditions and migratory, labor and social history of people arriving in a country. The challenges and advantages of an interdisciplinary, longitudinal and multilevel project to access migrant populations in a city are discussed and made visible through the analysis of Venezuelans in San José, Costa Rica, where family adjustments, social networks and the migratory project are examples of the migratory complexity rarely shown in censuses and surveys.

Keywords: : Venezuelans, ethno-survey, immigration, methodology, social networks

between transit and settlement: the ethnographic survey as a methodological tool for the study of recent venezuelan immigration to costa rica

In the last few years, Venezuelan immigration has turned certain cities into places of transit and clustering in multiple countries across Latin America. This article lays out the methodological and empirical contributions of the recent lamp-enir ethnographic survey on immigration, which assesses living conditions and the migratory, work, and social history of immigrants arriving to a given country. It delves into the use of an interdisciplinary, longitudinal, multi-level survey to reach migrant populations in a city through and the challenges and advantages of such a project. Specifically, the analysis focuses on Venezuelans in San Jose, Costa Rica, capturing the complexities of changing family configurations, social media, and the reception of immigrants in a way rarely achieved in censuses or surveys.

Keywords: Venezuelans, methodology, immigrants, ethnographic survey, social media.

Introduction

Until the xxIn the past, international migration in Latin America was characterized by highly concentrated movements in the form of regional patterns, such as the Southern Cone or Mesoamerica, and between neighboring countries, such as Mexico-United States, Colombia-Venezuela or Nicaragua-Costa Rica. The last two decades have witnessed a change in Latin American migratory movements, with the constant and more intense movement of people from South America to the north of the continent, to other non-traditional South American countries and to Central American countries that have become transit and destination countries. Current Latin American migrations are motivated by the negative effects of natural events, political and economic crises, as well as social violence in the countries of origin; an example of this is the unusual growth of Haitian, Venezuelan, Ecuadorian and even extracontinental migration, such as African and Asian migration from South America to Central and North American countries.

Since 2015, one of the most visible migratory flows in Latin America has been the Venezuelan one; according to Leonardo Vivas and Tomás Páez (2017) and Anitza Freitez (2019), in 2013 important political, economic and social changes began that caused a generalized crisis in the country during 2015, characterized by political and economic instability, which motivated the departure of millions of people in search of a better place to live.1 According to the Venezuelan Integration Platform for Refugees and Migrants (2023), 7.7 million Venezuelans became migrants and refugees in the world, representing 22.8% of the national population, estimated by the National Institute of Statistics (ine2013), at 33.7 million for that year. Most Venezuelans migrated to Latin American and Caribbean countries (6.5 million), especially to Colombia, Peru and Brazil. In Central America, Panama is the main receiving country of Venezuelan migrants, followed by Costa Rica, due to the double condition of being transit countries in the Latin American South-North migratory corridor to the United States, and because they have become destination countries.2

Costa Rica has historically been a country of Central American immigration, mostly of Nicaraguan population;3 but, in the last five years, it has established itself as a transit country for migrants arriving through Panama, through the Darien jungle region, the border between Central and South America. According to data from the Panamanian government (oim Costa Rica, 2023), at the Temporary Migratory Reception Station (etrm) of Los Planes (Gualaca), bordering the town of Paso Canoas, entrance to Costa Rica, in 2021, 126,000 departures/entries of migrants were recorded between Panama and Costa Rica, with a substantial increase to 226,000 departures/entries in 2022; in both years, a large part of the people entering through the Darien were Venezuelans (56 and 63%, respectively).

In October 2022, the Costa Rican government activated a bus route from its southern border with Panama to the country's northern border with Nicaragua, to facilitate the mobility of migrants whose only interest was to cross Costa Rican territory.4 Most of the people who pass through Costa Rica are in an irregular migratory situation; those with little or no economic resources use local transportation offered by the Costa Rican government or travel along local routes that reach the northern border with Nicaragua and generally pass through the Greater Metropolitan Area of San José (capital).

According to the International Organization for Migration (iom) Costa Rica (2023), although 84% of the migrants surveyed at the Costa Rica-Panama border indicated that they planned to stay in Costa Rica for one day or only a few hours (those who used Costa Rican government transportation), about 15% stay longer in the country. To these are added those whose final destination was this country and the migrants stranded as a result of the political-migratory uncertainty between the governments of the United States, Venezuela and the countries through which they must transit to reach North America: Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico. Given this scenario, the migratory profile of people in Costa Rica is diverse: some in irregular situation in transit through the country, people seeking international protection, refugees, regularized migrants with temporary or permanent residence and in special migratory categories.5 Faced with this migratory scenario, the oim Costa Rica (2023) estimates that approximately 300,000 Venezuelans reside in that country; although it estimates that 2% are in an irregular migratory situation, the majority would have a regular migratory status: 32% are refugee applicants, 12% are applicants for a different migratory status, 10% are temporary or permanent residents and the rest are in other statuses.

It is common for migrants staying in Costa Rica to settle in cities on the southern and northern borders of the country, as well as in the capital and its metropolitan area; some arrive in shelters or independent housing, while others live on the streets. Depending on the length of their stay in Costa Rica and their interest in continuing their migratory journey or settling in the country, they will need access to basic necessities such as food, lodging, work, immigration regularization, among others. In these recent migratory dynamics, the amount of Venezuelan people on the move is as relevant as the arrival and stay in the country, which has turned several Latin American cities into places of transit, temporary settlement or definitive destination.

Traditional sources of information on migratory processes in Latin America do not allow us to account for the aforementioned experiences; therefore, it is necessary to activate new ways of recording information for the creation of knowledge on current Latin American migratory flows. Population censuses and surveys, as well as existing administrative migration records are insufficient to know the amounts and experiences of recently arrived migrants, due to the temporality of their application, the representativeness of the diversity of populations in movement (transit, stay and residents) and the topics investigated.

In this scenario, the objective of this article is to show the methodology and results of a novel and updated source of information called Ethno-survey on recent immigration in Latin American host contexts (lamp-enir 2021) that collects information on migration processes through the combination of a survey with statistical representativeness that uses anthropological, sociological and demographic field strategies. The first section refers to the methodological contribution of the EtnoencuestThe first section is an interdisciplinary, multilevel and retrospective longitudinal study, with a specific sampling for populations that are difficult to access, such as migrants in a destination place. In the second section, in order to demonstrate the scope of the EthnoSurvey an analysis of the settlement process of Venezuelan migrants in San José, Costa Rica, is presented, based on issues such as family adjustments, social networks in migration according to the type of need and nationality of the people with whom they live; as well as local sociocultural participation during their stay in that country. This empirical case shows the complexity of current human mobility in Latin America and offers some final reflections regarding the contributions of the EthnoSurvey and the pending challenges for the knowledge of recent international migrations.

The EthnoSurveya method for studying recent immigration in host contexts

In the current scenario of information needs on migratory flows in the Latin American region, the purpose of this study was to learn about the migratory, labor and family history, as well as the living conditions of migrants arriving in Latin American cities. EthnoSurvey lamp-enircarried out in Colombia, Chile and Costa Rica by academics from several universities,6 in view of the lack of recent information in the censuses and surveys of the destination countries7 and insufficient information in the administrative migration records of transit and destination countries. The survey was conducted between November 2021 and March 2022 in five Latin American cities: Barranquilla, Cúcuta and Santa Marta (Colombia); Santiago (Chile) and San José (Costa Rica), targeting three migrant communities: Venezuelans in the five cities, Nicaraguans in Costa Rica and Haitians in Chile.

The ethno-survey or ethnographic survey, as opposed to a traditional survey, was developed as a quantitative and qualitative project from sociology and anthropology by Douglas Massey, Rafael Alarcón, Jorge Durand and Humberto González in 1987, to study Mexican emigration from the communities of origin. According to Massey and Chiara Capoferro (2006: 278-279):

the basic idea underlying the ethno-survey is that qualitative and quantitative procedures complement each other and that, properly combined, the weaknesses of one become the strengths of the other, producing a body of data with greater reliability and internal validity than would be possible using only one of these methods. While survey systems produce reliable quantitative data for statistical analysis, generalization, and replication, by ensuring quantitative rigor, they lose historical depth, richness of context, and the intuitive appeal of real life. Ethnographic studies, in contrast, capture the richness of the phenomenon studied. It is a multi-method technique of data collection that simultaneously applies ethnographic and survey methods within a single study.

The ethno-survey and its application are a method for the study of a specific subject and population, the basis of the Mexican Migration Project, mmp, The Latin American Migration Project was launched in 1987) and adapted to the Latin American reality through the Latin American Migration Project, lampsince 1998).8 According to Massey (1987), the methodology of the mmp is based on five aspects: the use of an ethno-survey (a questionnaire ad hoc); have a representative sample of migrants in several communities of origin; contain multilevel data; have life histories of international migrants; and have a representative sample of households in the chosen communities of origin and a non-representative sample of migrants settled in the United States (migration destination).

In the second decade of the xxiThe ethno-survey was adapted to study international migrants in cities of arrival or reception, that is, the questionnaire and the methodological strategy were modified from a place-of-origin perspective to a place-of-destination perspective. The first survey of information from this new perspective, called the Recent immigration ethno-survey (enir), was applied in 2018 in Montevideo, Uruguay, with the purpose of learning about the migration experience of migrants from Cuba, Dominican Republic, Peru and Venezuela in that Latin American city.9 Three years later, the enir was carried out in Colombia, Costa Rica and Chile (lamp-enir 2021) to Venezuelan, Nicaraguan and Haitian migrants, as noted above. For the selection of destination countries, study cities and migrant communities, we used the criterion of high rates of recent international immigration (greater than 5% with respect to the national population); this strategy would allow us to take advantage (methodologically) of the agglomeration of migrants in the same territory and make Latin American cities visible as territories of recent immigration, different from the traditional south-north migration flows whose main destination is the United States.

Adopting a migration perspective from the destination sites implied several challenges; perhaps the most important was the development of a methodological strategy to locate and dialogue with international migrants. Additional challenges were to adjust the questionnaire to relevant issues from an immigration perspective and to maintain comparability of information across cities and migrant communities through multilevel information (individual, family, city and country).

Regarding the methodological strategy, the task of estimating a representative sample of immigrants settled in a city was a statistical and social challenge. As Massey and Capoferro (2006: 284) point out, in the framework of the mmpThe main difficulty lies in constructing a sampling frame that includes all those who emigrate from a community, given that they are generally dispersed in a large number of towns and cities, both in the country [of departure] and abroad. Although in lamp-enir 2021 selected some of the Latin American cities and countries with the highest rates of recent international immigration, the difficulty of identifying and accessing the diversity of migrants persists for the following reasons:

- Being populations of low demographic density with respect to the national/local population residing in a specific urban territory. In most Latin American countries, the foreign population represents less than 10% of the total population, which makes its identification difficult, as it tends to be concentrated in special places, such as the capital of a country or border cities and in specific neighborhoods due to the low cost of housing.

- Lacking a registry of recently arrived immigrant population in a city, since there is no total population frame of international immigrants (N) from which to construct a representative sample (n), essential for a probability sampling based on chance (such as a simple random sample).

- No access to persons in irregular migratory status or in a situation of vulnerability. Migrants with undocumented status prefer not to be identified so as not to risk their stay in the country; on the other hand, persons seeking international protection opt for anonymity in order to safeguard their life, integrity and safety, while they are seeking refuge and, even when they have been recognized as refugees, because they feel vulnerable.

- Failure to record the diversity of profiles and migratory experiences of the study population. Studies on immigrants in places of destination show that there is a heterogeneity of people according to their country of origin, socio-demographic and migratory profile, moment or cohort of arrival, among other elements; therefore, it would be unrealistic and fragmentary to account for a single profile or migratory experience in view of the diversity of forms of immigration in the places of establishment.

lamp-enir 2021 responded to these challenges by creating an intentional sample of migrants contacted in the cities of arrival, which considers the diverse migratory profiles and achieves a sufficient number of interviewees to allow statistical inferences, representative of each migrant community. For this purpose, a Chain of Reference or Informant-Guided Sampling was used.10 (Respondent Driven Simpling, rds) which, according to Douglas Heckathorn (1997), was designed to recruit informants when there is no sample frame or it is difficult to access the target population, as was the case of migrants in irregular migratory status, those who were in a situation of vulnerability or with scattered residence in the city or in the metropolitan area of the Latin American capital.

The "Results Report" of lamp-enir 2021 (Giorguli et al2023: 12) points out that "The rds is structured as a chain of respondents starting with a limited number of informants, called 'seeds', who provide referrals of other potential respondents, who in turn provide new referrals." At lamp-enir 2021 migrant "seeds" were activated who were social actors with extensive networks in the migrant community of interest, such as a member of a social, community or religious organization, or the president of a migrant club. In each migrant community (Venezuelan, Haitian and Nicaraguan) in each Latin American city, the "seeds" referred three known migrants and they, in turn, suggested three other people and so on; in this way, each new migrant contacted became an informant and a recruiter.11

This is how the rds combines snowball sampling with a mathematical model that allows the creation of a sample weighting for each migrant community by city (Giorguli et al., 2023: 13). The sample of lamp-enir 2021 is comprised of 1,400 immigrant respondents (1,000 Venezuelans, 200 Haitians and 200 Nicaraguans) residing in the five selected Latin American host cities.12

The adoption of a sampling rds The purpose was also to ensure the heterogeneity of the sociodemographic and migratory profiles within each informant network; to this end, the greatest number of "waves" (succession) of new referrals was monitored and sought to ensure a greater diversity of migratory profiles ("depth" of the network). The quality of the sampling was evaluated on the basis of several indicators: (i) homophily, which is the preference of a specific person (called "ego") to give references of individuals similar to him/her, which allows measuring the similarity between the informant and the referent (sex and educational level characteristics were used as control variables); ii) reciprocity between the informant and the referrer, i.e., having information that they knew each other and, therefore, are part of the same social network; and iii) the necessary depth of the reference chains to evaluate how far the characteristics of the sample obtained are different from the characteristics of the initial sample ("seeds") (Giorguli et al., 2023).

Thus, the methodological strategy used allowed the central objective of "contributing to the production of quality statistical information on the living conditions, biographical trajectories, integration processes in the places of destination, aspirations and future plans of the immigrant population in Latin American host cities" (Giorguli, "The integration of the immigrant population in Latin American host cities"). et al. 2023: 8). The EthnoSurvey is, therefore, an instrument and a method for approaching the reality of a longitudinal-retrospective and current type, which allows us to know the migratory, labor and social trajectory of migrants and their families throughout their lives; therefore, it includes information from before embarking on the journey, upon arrival in the city of study (the first year), in specific periods (such as during the covid-19 pandemic) and at the time of the application of the ethno-survey.

As Massey and Capoferro (2006: 282) point out, with respect to the methodology lamp-enirAlthough individuals may constitute the units of analysis, their decisions are typically made in broader social and economic contexts, which structure and constrain individual decisions"; consequently, "individuals may constitute the units of analysis, but their decisions are typically made in broader social and economic contexts, which structure and constrain individual decisions", lamp-enir 2021 maintains the purpose of being a multilevel information source. The EthnoSurvey collects the following data: (i) individuals, which includes the international migrants interviewed and the members of their family unit (whether or not they are migrants, regardless of their place of residence); in addition, person-year records are kept to account for the life history of the migrant informants; ii) at the household and housing level of the migrants; and iii) at the city and country level of study (Latin American cities and countries); through the compilation of sociodemographic, economic, labor and urban indicators that allow contextualizing the places where the migratory experience of the interviewees takes place. These multiple levels of observation of international migration allow us to propose and estimate multilevel explanatory models.13 Finally, from an immigration perspective, lamp-enir 2021 contains information on employment, education, health, residential and social inclusion in the destination city.

With the purpose of showing the scope of the EthnoSurveyThe following is an empirical analysis of Venezuelan migrants in San Jose, Costa Rica, surveyed in lamp-enir 2021, through some selected indicators that allow us to know the population profile and the migratory experience in Costa Rican territory.14

Venezuelans in Costa Rica: Diverse Population and Changing Dynamics

The following is a selection of sociodemographic characteristics and the international migration experience of Venezuelan residents in San José, Costa Rica, in 2021, from a micro and meso social perspective.

a) Sociodemographic and family profile

Migrants are not isolated subjects, but are part of broader social groups, such as the family or the community. With this basic idea, I reconstruct the structure of the family to which each Venezuelan migrant informant belongs based on the kinship relationship (spouse, child or other relative), considering the country of residence in which each relative is located and the country of birth. These elements make it possible to identify the existence of complete migrant families, transnational families (at least between two countries) and families with members in a third country (other than the country of origin and Costa Rica); all of them with or without family ties and responsibilities.

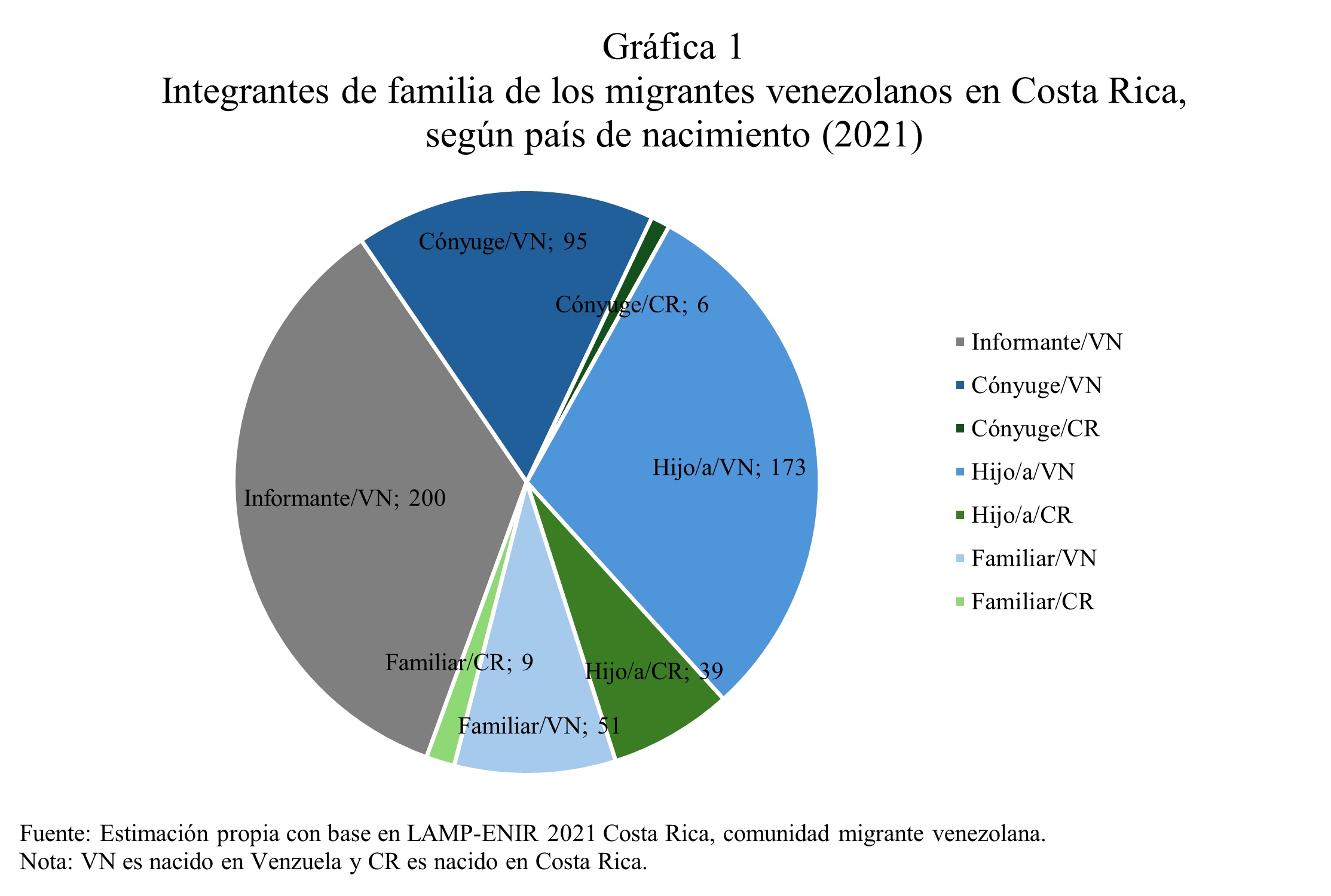

In San José, Costa Rica, 200 Venezuelan migrants were interviewed who, after identifying their family members, yielded a total of 626 people, including the informant. As can be seen in Graph 1, 90% have a nuclear type of kinship (34% informant, 17% spouse and 37% child) and only 10% have an extended or composite type of kinship (parent, sibling, nephew, uncle and/or grandparent, among others). In addition, although most of the declared relatives are persons born in Venezuela, 9% were born in Costa Rica, whose kinship relationship is spouse, child or another relative such as brother-in-law, grandchild and father-in-law (1, 7 and 1%, respectively); these indicators show the transition or conformation of binational families in the Latin American cities of destination, such as San José. In these Venezuelan-Costa Rican families, it would be interesting to investigate differentiated experiences in access to education, health care or work in the face of the national-foreigner dyad of each family member.

Although the majority of people indicate living in the same household as the migrant informant (86%), there is a small proportion who live in another colony or city in Costa Rica (4%), another who stayed living in Venezuela (8%) and, finally, one who lives in a country other than Costa Rica and Venezuela (2%). This information shows that in one out of every ten Venezuelan families there is evidence of transnational families. This family structure reveals the diversity of family situations experienced by international migrants: separations, reunifications or joint emigrations that maintain or dilute the family nucleus, the creation of new families or the circumstance of remaining without family members (single-person households); these family situations may be stages of the same migratory-family process throughout the time of exposure to international migration.

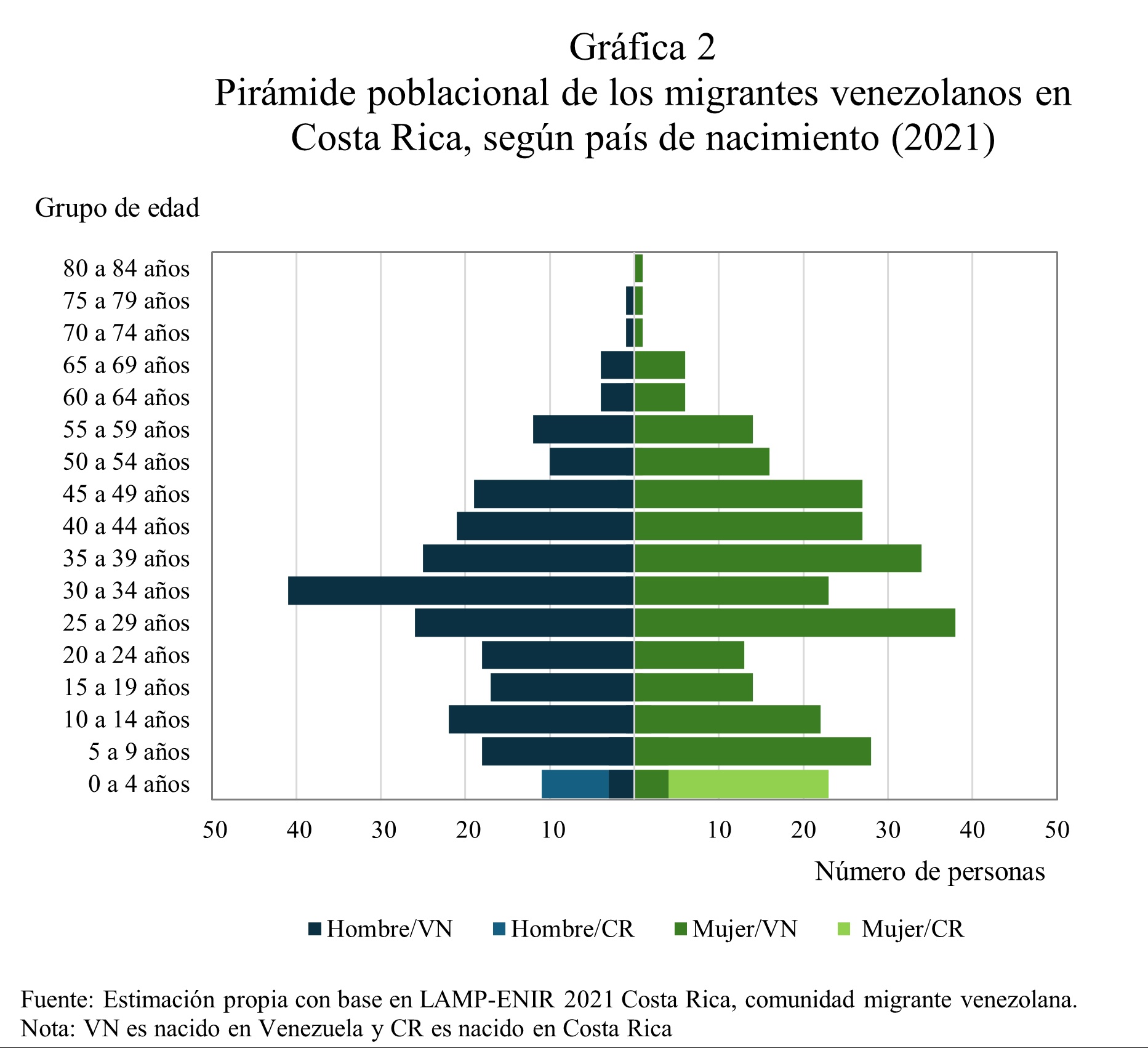

A representative sociodemographic indicator of the stage of life in which people find themselves, in this case those linked to migratory processes, is the distribution of the population by age group and sex. As can be seen in the population pyramid (Graph 2), the population structure of the Venezuelan migrant community in Costa Rica refers to a population with a diverse profile, composed of minors, people of working age and older adults, a structure far from a migratory-labor profile (which usually prevails) and consistent with generalized migratory processes and the product of a long period of exposure to emigration. From the country of arrival, this age diversity allows us to approach the needs of the arriving migrant community, differentiating between age and sex, such as educational, labor and health needs. It is noteworthy that there is a high proportion of children aged 0-4 years born in Costa Rica, with a higher prevalence among females than males (85 and 73%, Costa Rican girls and boys, respectively).

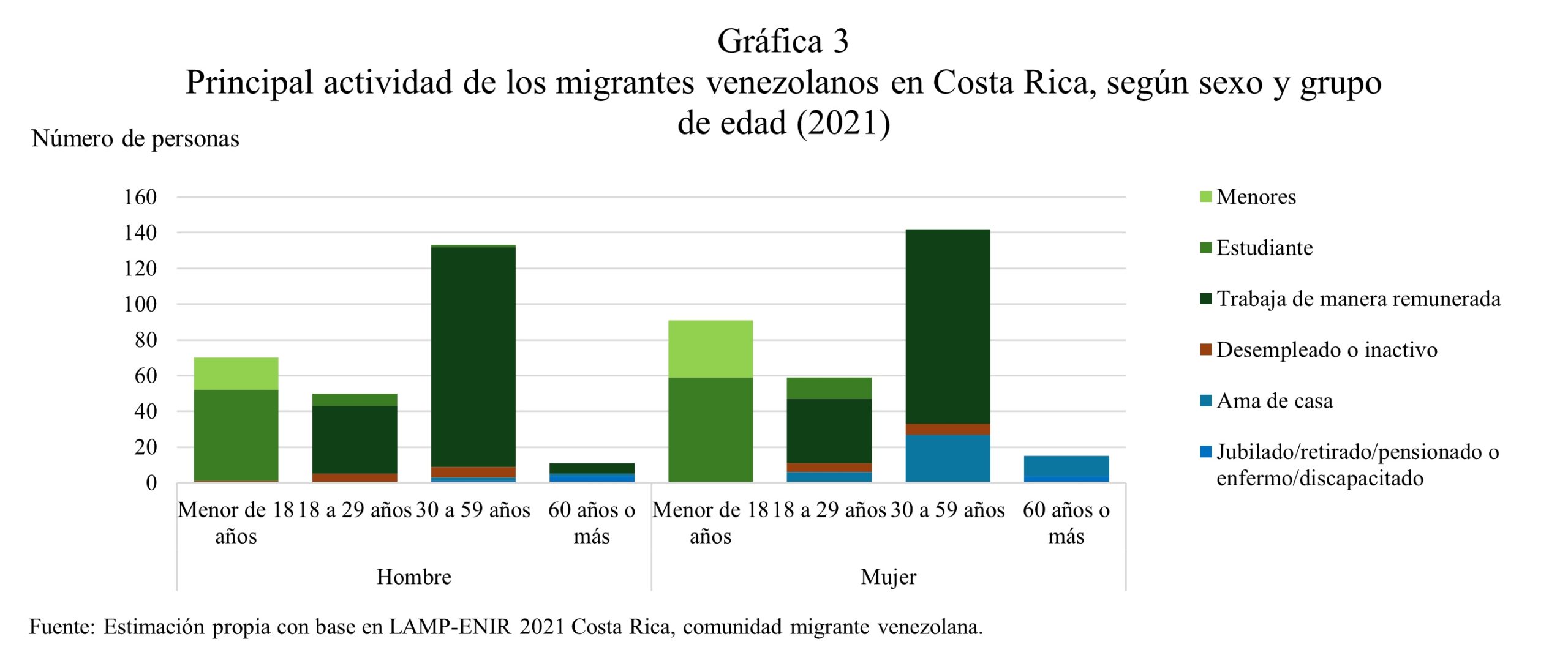

In daily life, most Venezuelan children and adolescents attend school, and there are no records of minors incorporated into the Costa Rican labor market. Figure 3 shows that the main activity of the young population is paid work and that almost all males were working (91%), while only 69% of females were working. It is noteworthy that among young Venezuelans between 18 and 29 years of age there are still people who report being students, both among women and men. In contrast to the main activity of men, an important part of Venezuelan women work as housewives, showing the prevalence of traditional gender roles.

For a large proportion of people of working age, joining the labor market is an essential need to obtain resources for daily life. Among workers, only a small proportion of Venezuelans were professionals (5% had higher education), most had at least one year of secondary education (53% had completed it and 10% had not) and a third had basic education (29% completed and 3% had not). Based on these educational levels, it can be noted that, despite the fact that more than half of the people had more than a basic education, it is a migrant community with educational diversity.

In terms of work, male Venezuelan migrants held various types of jobs: transport drivers (26%), professionals (15%), public, private or social employees (11%); maintenance workers (10%), merchants and sales agents (10%) and workers in establishments (8%). Women were mainly traders and sales agents (22%), administrative workers (14%), street vendors (11%), domestic workers (10%) and workers in establishments (9%). It is relevant to point out that half of the professionals worked as administrative workers, merchants, sales agents or street vendors, occupations with low qualifications when considering the level of education attained; this characteristic is common among migrants who have recently arrived in a country, particularly when they do not have a migratory document that allows them to carry out a remunerated economic activity or when they require proof of education to support their profession.

b) The Venezuela-Costa Rica migration experience

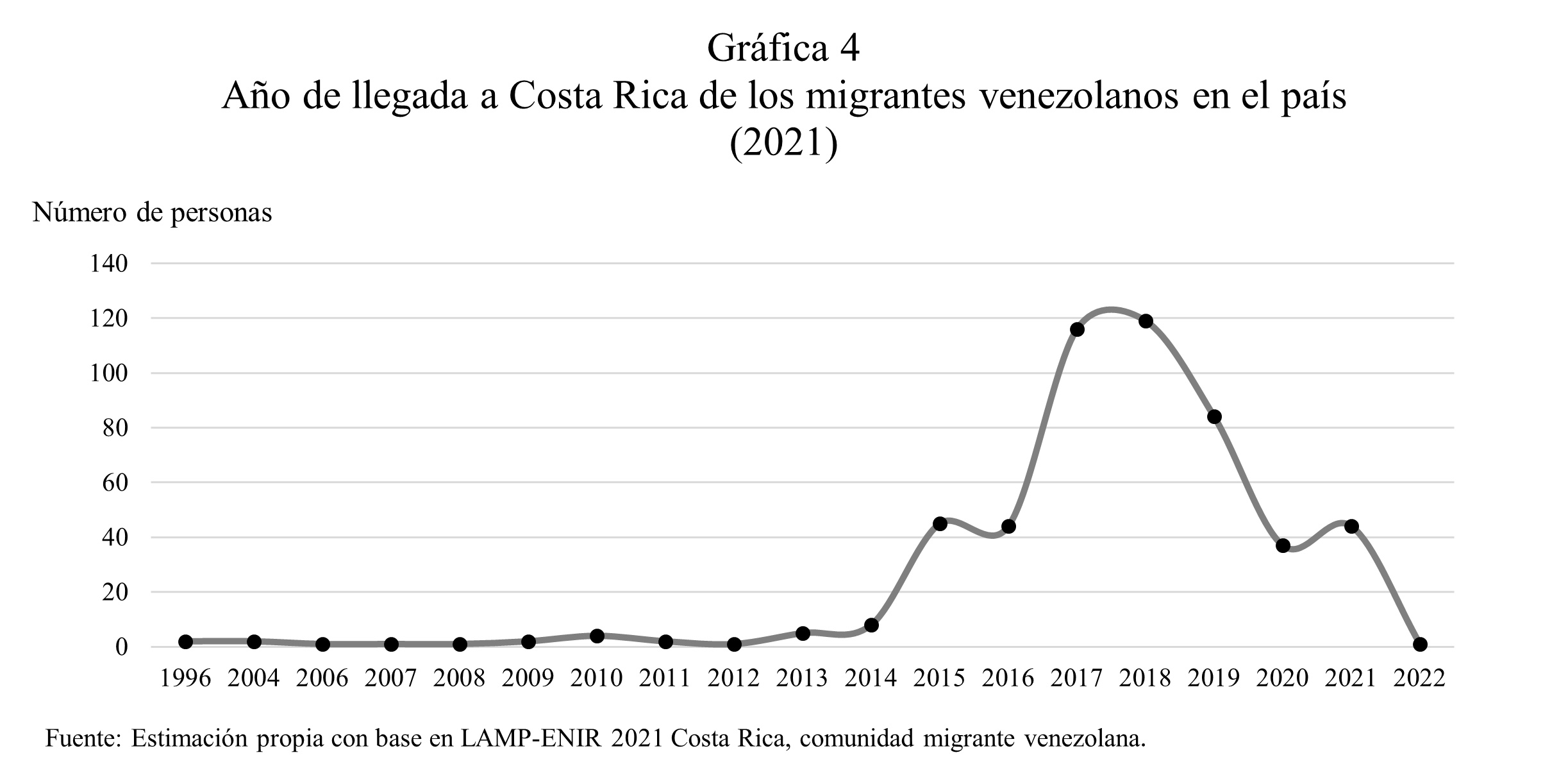

Based on the Venezuelan population registered at lamp-enir 2021, the oldest migrant arrived in Costa Rica in 1996 and only 5% of those interviewed arrived between that year and 2014. The year 2015 is iconic in Venezuelan immigration to Costa Rica, as it marked the beginning of the flow of Venezuelans to the country. As seen in Graph 4, the highest point of Venezuelan immigration occurred between 2017 and 2018 when 45% of all persons interviewed arrived. The period between 2019 and 2022, despite showing a downward trend in immigration, represents a third of Venezuelan arrivals to Costa Rican territory; it should be noted that this decrease in immigration does not mean a decrease in the transit of Venezuelans through the country, which continued persistently. The Venezuelan migratory pattern observed in Costa Rica coincides with international trends of this migratory flow to other Latin American countries.

According to the data of lamp-enir 2021, for 89% of the Venezuelan migrants interviewed, the trip to Costa Rica was their first international migration.15 As has been shown at the beginning of this paper and in various studies on Venezuelan migration, family migration (complete or incomplete family units) has been a form of international mobility. The EthnoSurvey records that 99% of the Venezuelan migrant minors traveled accompanied, that 27% of the mothers and 12% of the fathers of the migrant informants had migrated to Costa Rica, showing evidence of the existence of generational family migration networks.

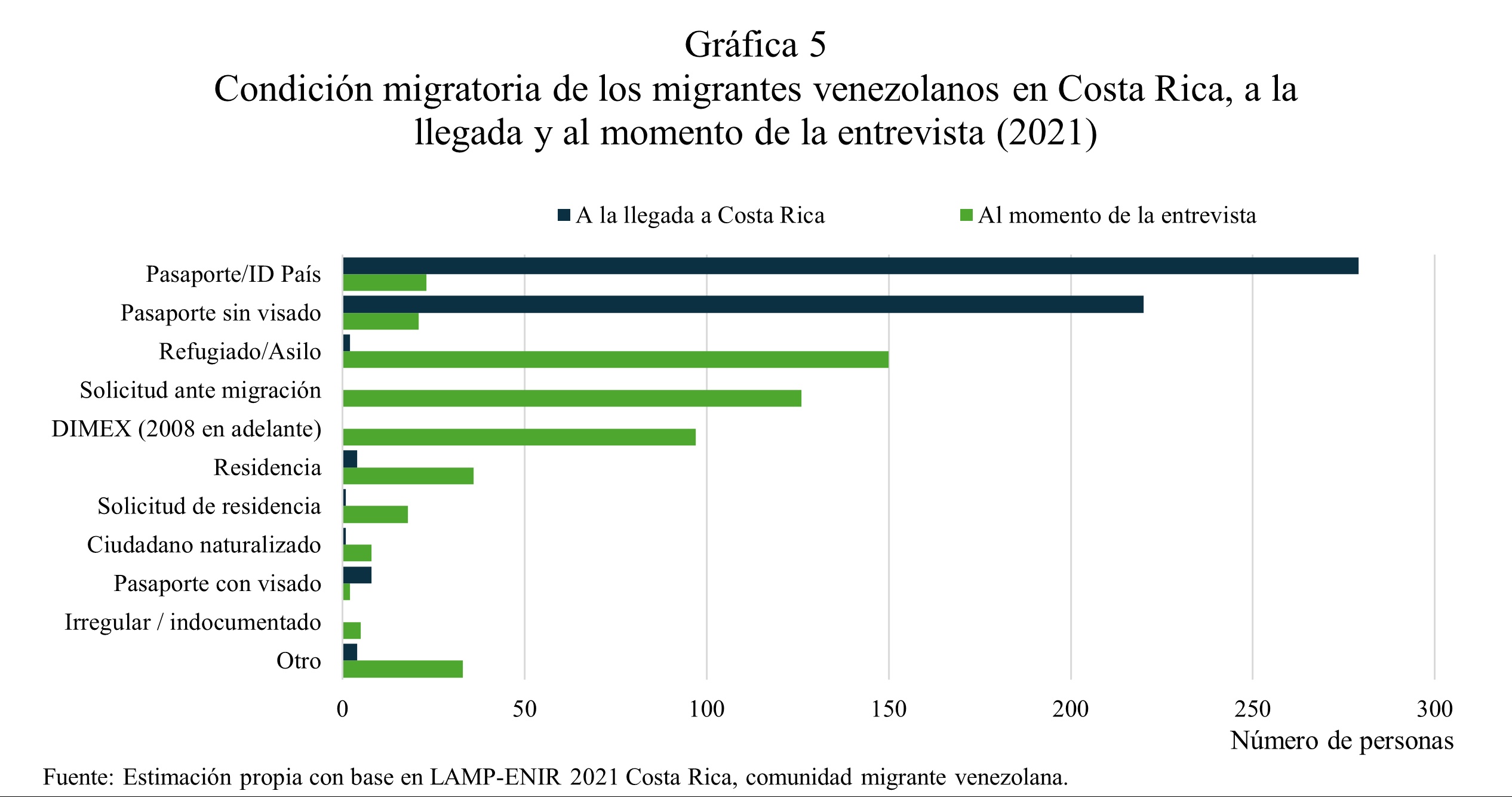

An advantage of lamp-enir 2021 is the compilation of the migration experience over time. An example of this is the migratory status of individuals upon arrival in a country and over time, up to the time of the interview. The most common assumption in this regard is that a person experiences changes in migration status from irregular to regular status over time. As shown in Graph 5, the majority of Venezuelan residents interviewed in Costa Rican territory indicated having arrived in the country in a regular manner, with documents such as a tourist passport or a passport without the corresponding visa; however, once time passes, the migratory status changes in various directions, towards requests for refuge or asylum, requests for residence, and enrollment in one-time or exceptional programs for temporary residence permits. However, it must be said that some people continue their stay in the country with a tourist passport and even move towards an irregular or undocumented migratory situation when the validity of a previous migratory document expires.

lamp-enir 2021 is one of the few sources of information that makes visible the coexistence of migrant populations in regular and irregular migratory status, as well as the diversity of migratory forms used by people throughout their migratory experience. It is important to point out that this status is related to the migratory actions and programs adopted by each country of arrival, and that a regular migratory status allows migrants to have access to resources, services and rights that allow them to satisfy essential needs during their stay or permanent residence: housing, paid work, medical assistance, school incorporation, among others. Therefore, any form of migratory regularization contributes to the reduction of insecurities and vulnerabilities in the territory of arrival.

c) Social networks and local participation in migration

Leaving the country, transit and arrival in a new country are iconic moments that mark people's international migration experience. During the "time exposed to international migration", understood as the time span of the migration process (number of years, for example) from the departure of the country of origin to the present, travel and living conditions change and depend on the resources available to the person on the move. In this migratory experience, the choice of the country to which to migrate is usually determined by the previous migratory experience, by the migratory experience of others (relatives, friends or fellow countrymen) and even be defined during the migratory journey. In the same way, social ties or networks shape the migratory experience in the search for a place to rest or live, access to food, medical care, migratory regularization, knowledge of the city, among others.

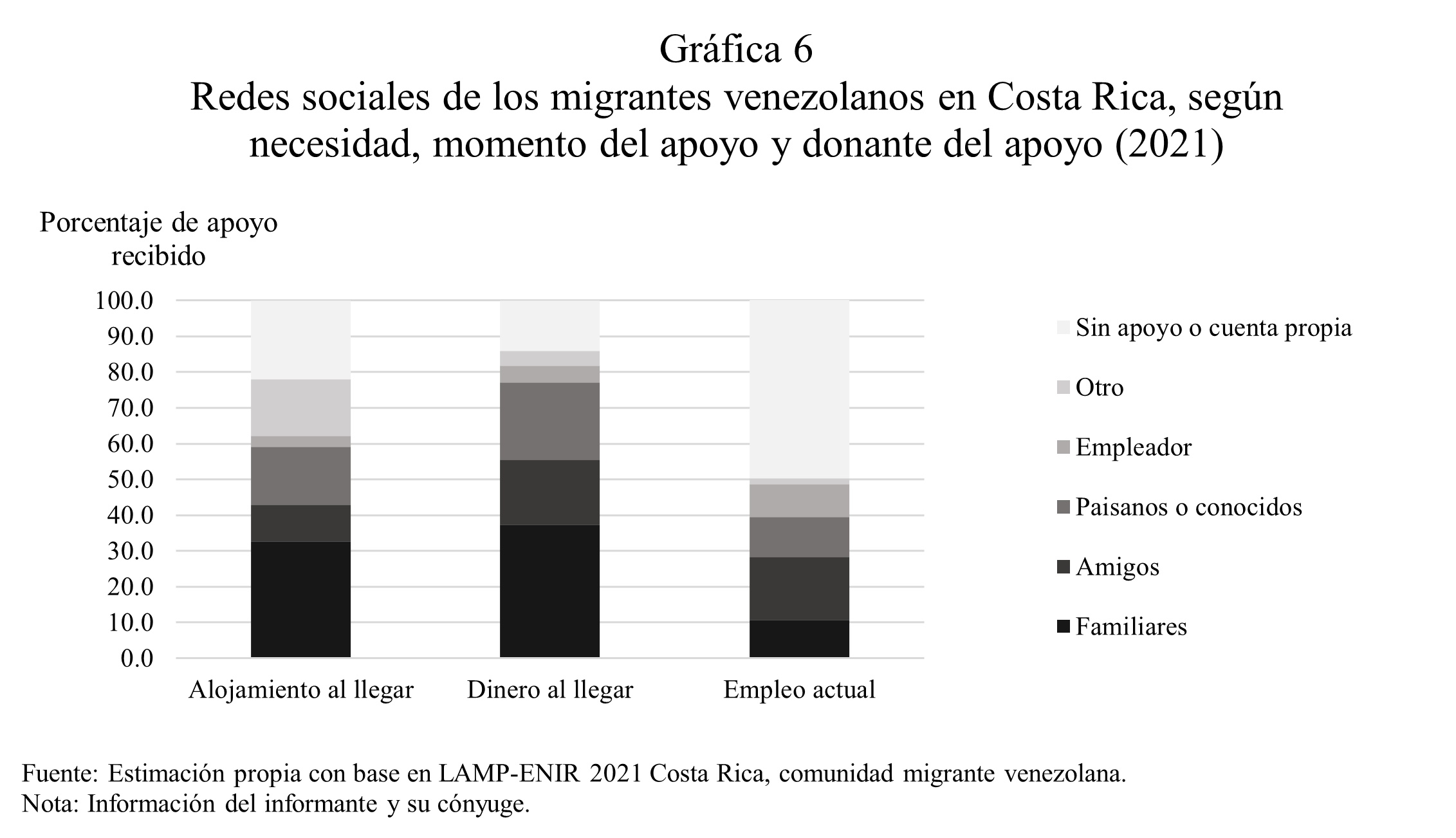

According to lamp-enir 2021, 80% of the informant migrants and their spouses relied on some social network upon arrival in Costa Rica to access housing, while 90% did so to obtain some economic support when needed. As shown in Figure 6, in both needs, the main support network is the family (32 and 37%, respectively), followed by the network of fellow countrymen (16 and 21%) and the network of friends (10 and 18%); but it is noteworthy that employers also served as a support for obtaining housing or money when needed (3 and 5%, respectively).16 The data show that support for the Venezuelan community is based on family relationships.

In the search for a job, the support received from a social network is less, compared to the needs for housing and economic support upon arrival in Costa Rica; half of the informants and their spouse obtained their current job on their own, while the other half obtained it through friendship networks (18%), acquaintances (11%) and family (11%), reversing the order of importance of the networks for housing and economic support. Likewise, 9% reported using other strategies such as searching for jobs in newspaper ads, employment agencies, going directly to workspaces or searching on social networks such as Facebook.

Although lamp-enir 2021 refers to forms of job search that are mutually exclusive, other studies have shown that migrants in destination cities activate diverse and combined forms of job search (Nájera, 2022). The socio-labor networks essentially involve people from the same Venezuelan migrant community (78%), followed by Costa Rican nationals (17%) and finally migrants from other countries of origin.

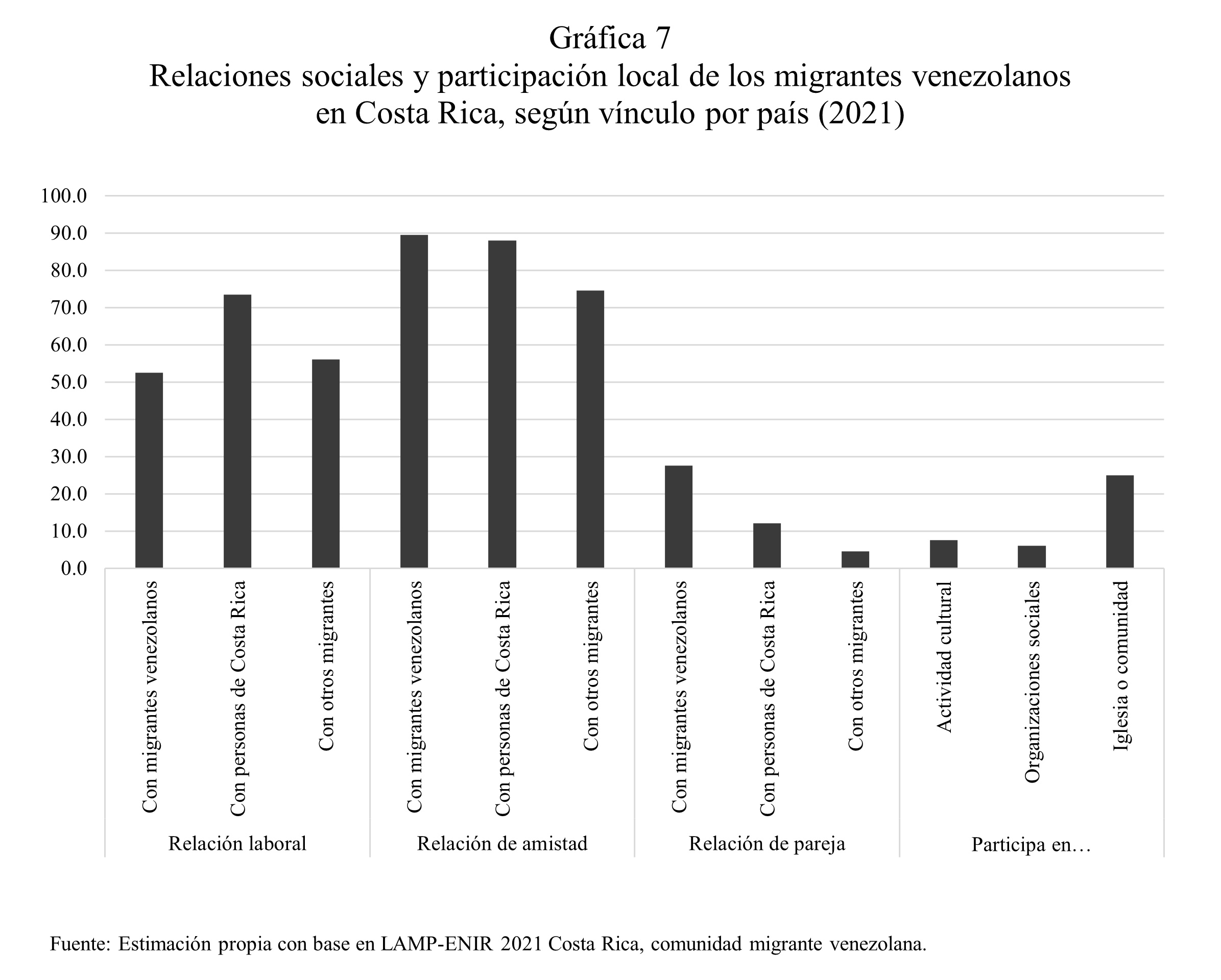

One of the usual indicators of migrants' desire to remain in a new country is the ties they have with the people of the society they are arriving in.17 lamp-enir 2021 inquired about the work, friendship and partner networks that Venezuelan migrants in Costa Rica maintain with nationals, with migrants from their own community and with migrants of other nationalities. As Figure 7 shows, work relationships are more common with Costa Ricans and friendship relationships with people from the same Venezuelan migrant community (73 and 89%, respectively); while couple relationships also occur essentially among Venezuelan migrants.

Sociocultural interaction between migrants and the local population occurs not only through social ties or networks, but also through people's participation in cultural activities, in social organizations and in community or religious spaces. Although these forms of social interaction are less prevalent than work, friendship and couple social networks, religious or community participation stands out as an important form of local socialization. An additional finding is that there is a higher percentage of migrants with social relations and local participation in Costa Rica among Venezuelan migrants who have been residing in the country for more years, compared to recently arrived migrants; this aspect supports the hypothesis that the longer the time spent in a country, the greater the sociocultural inclusion.

The EthnoSurvey also shows that social networks exist both in the country of arrival and with the country of origin. Although the majority of Venezuelans interviewed indicated that since emigrating they have not returned to visit their country of origin (93%), a significant proportion of them maintain contact with relatives or friends in Venezuela on a constant basis (63% daily and 31% weekly) and more than half of the informants and spouses reported that they send remittances to relatives in Venezuela (60%), which are usually sent to the mother (44%), father (18%), siblings (14%) or children (9%), who use these resources for the purchase of food (64%) and payment of medical expenses (27%). Thus, social networks in international migration are a dimension of analysis that refers not only to migrants and their families, but also to the local-national community, other migrant communities and family members in the country of origin.

d) Motivations and migration project

Finally, in the migration experience, Venezuelans interviewed in Costa Rica indicated that the main reasons for leaving Venezuela were economic-labor (31%), political issues (28%), violence and insecurity in the country (17%), desire for personal growth (9%), family reunification (7%), seeking medical treatment (4%) and others.18 These data show the diversity of motivations and profiles of international migrants arriving in Costa Rica, whose composition is not only of economic migrants in search of work and a better standard of living, but also of people in need of international protection due to political persecution, family reunification and better basic services such as health and education.

On the other hand, Venezuelan informants and spouses indicated that they chose Costa Rica as their destination because they had social networks in the country (family or friends) (25%), because it was a quiet and safe country (22%), because there were job opportunities (12%) and because of its political stability (7%), among the most relevant motivations.19 Interestingly, in Venezuelan migration, political reasons, insecurity and the search for services or basic rights stand out as causes for international mobility.

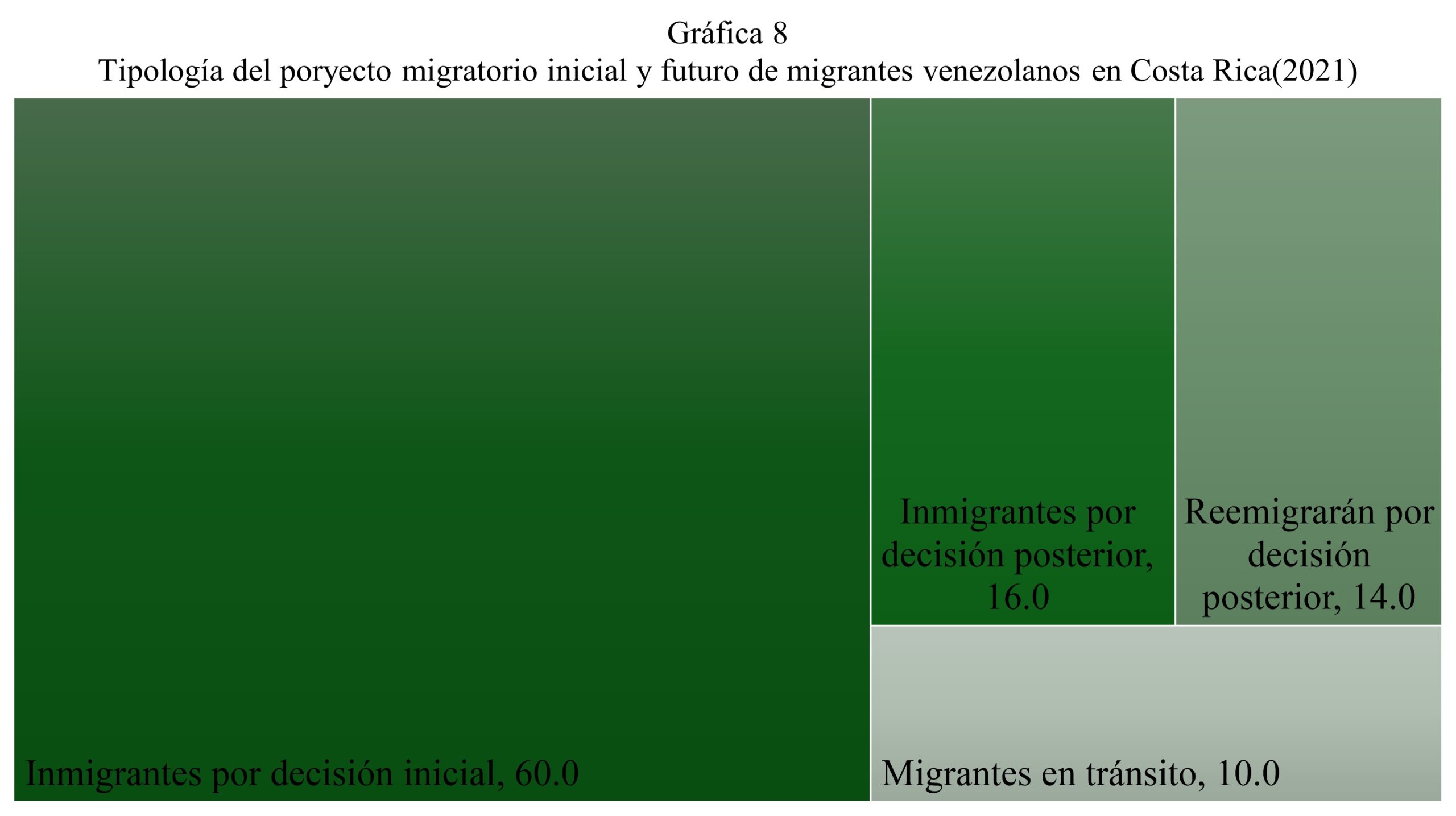

lamp-enir is a source of information that shows that in international migration, a migration project can change over time for various reasons and during transit to the planned destination or while in that country. Most of the Venezuelan informants and spouses residing in Costa Rica had as their migration project to stay in that country (74%); however, as shown in Graph 8, 14% indicated their interest in migrating to another country in the next three years. Among those who initially had no interest in staying in Costa Rica (24%), 10% continued with the desire to migrate to another country (transit migrants), but 16% changed their minds and decided to settle there.

The empirical analysis of the Venezuelan migrant community in San José, Costa Rica, carried out here reveals the challenges of recent Latin American international migration experiences which, despite its apparent "migratory youth", has built networks and socio-familial and paisanaje (migrant community) ties very rapidly in the last seven years of constant arrival of the Venezuelan population to the country. Additionally, lamp-enir 2021 shows the heterogeneity of the socio-demographic profiles of those who move, of the motivations for doing so and of the forms of local incorporation in the places of arrival or destination (through the migratory condition, social networks, local participation) with impacts on the migratory projects, which are altered by the time exposed to immigration in Costa Rica and the migratory experience lived.

Final thoughts

Within the framework of the new geographies of international migratory flows in Latin America, Costa Rica stands out for its current multiple migratory character as a transit country for migrants as it is an intermediate point on the route to the United States and as a place of establishment or migratory destination because it is considered an attractive territory due to the opportunities and living conditions for Venezuelans. Although Costa Rica has historically been a country of Nicaraguan border immigration, Venezuelan migration (as well as other Latin American, Caribbean and even extracontinental migration) has positioned it as a transit and immigration country in recent years. Migratory flows entering through the southern Panama-Costa Rica border, via the Darien, have shaped a country that currently combines actions (and reactions) to assist people in transit through its territory, such as offering fast means of transportation to cross it, as well as actions for the integration of those people who settle in the country, through migration regulation programs or support for temporary settlement from the State or in conjunction with international organizations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).unhcr) or with civil society organizations.

The Recent immigration ethno-survey is a method for generating information that combines a specific retrospective longitudinal questionnaire to account for the immigration process with a methodology for accessing hard-to-reach populations, which helps to understand and account for the complexity of current human mobility in Latin America. Among its advantages is having updated and specific information on the immigration process that is not offered by population censuses and surveys or administrative records, in addition to making visible the sociodemographic and migratory heterogeneity of migrants on the move. In addition, it collects information at different times (throughout the person's life), territories (origin, transit and arrival) and levels of observation (migrants, their families, the household, the community and the country), in which the context is relevant for framing the migratory experience of people on the move.

Finally, surveys such as lamp-enir 2021 can become a substantive input for the design and strengthening of public policies for the care of migrants. Although the Central American region has historically been a territory with its own intraregional migratory dynamics, it is currently also an uncertain migratory territory affected by continental and extracontinental migrations.

Bibliography

Giorguli, Silvia, David Lindstrom, Jéssica Nájera, Victoria Prieto, Clara Márquez y Miguel Amaro (2023). Plataforma de Datos Territoriales para la Integración de Inmigrantes. Etnoencuesta de inmigración reciente en contextos de acogida latinoamericanos, lamp-enir 2021. Ciudad de México. https://mmp-lamp.colmex.mx/wp-content/uploads/informe-de-resultados-lamp-emir-2021.pdf

Freitez, Anitza (2019). “Crisis humanitaria y migración forzada desde Venezuela”, en Luciana Gandini, Fernando Lozano y Victoria Prieto (eds.). Crisis y migración de población venezolana. Entre la desprotección y la seguridad jurídica en Latinoamérica. México: unam, pp. 33-58. https://www.sdi.unam.mx/docs/libros/SUDIMER-CyMdPV.pdf

Heckathorn, Douglas D. (1997). “Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations”, Social Problems, 44(2), pp. 174-199. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096941

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (ine) (2013). Venezuela. Proyección de la población, según entidad y sexo, 2000-2050 (año calendario). Caracas: Gobierno Bolivariano de Venezuela. http://www.ine.gob.ve/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=98&Itemid=51

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (inec) (2016). Resultados generales del x Censo Nacional de Población y vi de Vivienda 2011. San José. https://admin.inec.cr/sites/default/files/media/repoblaccenso2011-16_2.pdf

Koechlin, José, Joaquín Rodríguez y Cecilia Estada (coords.) (2021). Inserción laboral de la inmigración venezolana en Latinoamérica. Madrid: obimid. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=831513

Massey, Douglas (1987). “The Ethnosurvey in Theory and Practice”, International Migration Review, vol. 21, núm. 4, pp. 1498-1522. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546522

—, Rafael Alarcón, Jorge Durand y Humberto González (1987). Return to Aztlán: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

— y Chiara Capoferro (2006). “La medición de la migración indocumentada”, en Alejandro Portes y Josh De Wind (coords.). Repensando las migraciones. Nuevas perspectivas teóricas y empíricas. México: Miguel Ángel Porrúa/uaz/ Instituto Nacional de Migración, pp. 269-299.

Nájera, Jessica (2022). “Procesos de establecimiento de migrantes latinoamericanos recientes en la Ciudad de México: el trabajo como un medio esencial, Notas de Población, 49 (114), pp. 129-151.

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (oim) Costa Rica (2023). Contexto migratorio en Costa Rica y últimas tendencias. Reporte de situación. Febrero. https://costarica.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1016/files/documents/2023-05/resumen_mig_cr_02_2023.pdf

Plataforma de Integración para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela (2023). Refugiados y migrantes de Venezuela. Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes, R4V. Recuperado el 3 de diciembre de 2024. https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes

Valero, Mario (2018). “Venezuela, migraciones y territorios fronterizos”, Línea Imaginaria, 6(3), pp. 1-24.

Vivas, Leonardo y Tomás Páez (2017). The Venezuelan Diaspora, Another Impending Crisis? Washington: Freedom House Report.

Jéssica Nájera is a professor-researcher at the Center for Demographic, Urban and Environmental Studies at El Colegio de México, since 2015; BA in Economics, MA in Demography and PhD in Population Studies. Member of the sni and research networks on migration, family and work, and support groups for migrants. Her research focuses on the links between migration and work from a sociodemographic perspective, with quantitative and qualitative methodologies. She develops particular topics such as cross-border mobilities and migrations between Mexico and Guatemala; international migrations in Latin America, particularly in the Mesoamerican region; migratory flows and integration of migrants in Mexico; family, work and gender. She was responsible for the Survey on Migration in the Southern Border of Mexico (Emif Sur) from 2005 to 2008; and since 2019 she is a member of the Project on Mexican/Mesoamerican Migration (mmp) and Latin America (lamp-enir), projects of El Colegio de México and Brown University.