From the bottom of a shoebox, a trickle of memory emerges: some photographs on rural communication.

- Daniel Murillo Licea

- ― see biodata

From the bottom of a shoebox, a trickle of memory emerges: some photographs on rural communication.

Receipt: September 12, 2024

Acceptance: March 16, 2025

Abstract

Based on a photographic archive rescued from a shoebox, which shows some moments of a development project in the humid tropics of Mexico and the actions of the Rural Communication System, a methodology is proposed to systematize, classify and give context to a corpus of images derived from it.

Key words: rural communication, Proderith, humid tropics, eastern Yucatan, Pujal Coy ii.

from the bottom of a shoebox, a thread of memory: photographs of rural communication

A collection of photographs found in a shoebox reveals certain moments of a development project in the humid tropics of Mexico: the Rural Communication System, a government program to improve communications among local farmers. The article then lays out a methodology to classify and contextualize the photographs in the collection.

Keywords: rural communication, Proderith, humid tropics, eastern Yucatán, Pujal Coy ii.

Introduction, behind the scenes and a context

Sometimes the thread of memory suddenly appears, as it did with that shoebox abandoned in a warehouse of the Mexican Institute of Water Technology (Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua (imta) which contained old photographs of communication projects for hydraulic development. But let's go in order.

The imta had as its predecessor the National Water Plan Commission (cpnh), created on August 7, 1986 by presidential decree (dof, 07/08/1986). Its sector head was the then Secretariat of Agriculture and Water Resources (sarh). The reform of the water sector included the creation of the National Water Commission (cna) (1989), the enactment of the National Water Law (1992) and its Regulations (1994) and the change from the water sector to the environmental sector, with the creation (1994) of the Ministry of the Environment, Natural Resources and Fisheries (Semarnap) and a public policy orientation towards the market and the environment. Both the Conagua and the imta were removed to the environmental sector, with the disappearance of the sarh in 1994 and gave way to the creation of two state secretariats: Semarnap and the Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock and Rural Development.

The imta included the areas of irrigation and drainage and rural communication, transferred from its institutional antecedent, the cpnhwhich were pillars in its organizational chart. Both areas shared the common past of having developed and participated in a large-scale program: the Integrated Rural Development Program for the Humid Tropics (Proderith), with the participation of the Food and Agricultural Organization (fao) and with financing from the World Bank. Proderith had two phases: the first, from 1978 to 1984, and the second, from 1986 to 1995. The third phase, although under negotiation, never materialized. I was fortunate enough to begin my professional career working on the Pujal Coy iiThe company was founded in 1990, and later contributed to the design and start-up of the Northwest Regional Unit, based in Ciudad Obregón, Sonora.

The Rural Communication System (scr) was designed on the basis of the experiences developed in South America by experts who were contracted by the fao. Through a project1 involving the faoto the imta Yet the sarh (as head of sector), this international organization provided the scr The project also included a coordinator or main advisor and a group of advisors (some hired for years and others for specific tasks) and the purchase of videographic equipment, as well as a budget for installing local and regional units in the field, which made it possible to speed up the processes and avoid running up against national administrative mechanisms. So in the scr communication specialists, photographers, filmmakers, anthropologists, graphic designers and video documentary makers worked together, some from the imta and others contracted by the fao.

The socioeconomic context of that time had the development of the humid tropics as a public policy orientation, since there were conditions of extreme poverty, malnutrition, gastrointestinal diseases, low agricultural and livestock production, as well as environmental degradation. The objectives of the scr aimed at "raising production and productivity levels in the Mexican Humid Tropics and improving the living and working conditions of the rural population by making better use and conserving the available natural resources" (fao, 2009: 306).

The scr was responsible for extensive field work and training of farmers in the use of audiovisual tools; however, the communication approach went beyond simple "training". Some current methodologies that are believed to be new or completely innovative were already being used in the field: the now called "participatory workshops" were carried out with groups of inhabitants of many localities and with specific groups (women, cattle ranchers, farmers, etc.), and the objective was for the farmers to participate in the workshops.), and the objective was for the farmers to define their own Local Development Plans; the group dynamics, discussion groups, after the projection of audiovisual materials and interactive cinema that are used today were already carried out since the late 1970s in this project and were called "application sessions", a very unfortunate name, by the way; the concept of "transmedia" was practically applied through the use of various media such as videos, primers (written materials) and discussion between farmers and technicians, through the Audiovisual Educational Units; the "map of actors" had its interpretation through the Communication Network, an intricate exercise, together with the farmers themselves, to identify actors, communicative flows, discourses, practices, focuses of power, mediations and messages. Part of this model was designed and promoted by Manuel Calvelo and was called "multimedia mass pedagogy" (Calvelo, 1998: 2013). Previously, Calvelo had applied it -through trial and error- in Peru, in a project known as Centro de Servicios de Pedagogía Audiovisual para la Capacitación (Center of Audiovisual Pedagogy Services for Training) (cespac).2

In reality, the rural communication approach was to achieve a dialogue (mediation) between peasant groups and public institutions: the idea was to combine peasant knowledge with agricultural technology - what is now called "knowledge recovery" in peasant populations - and to stimulate reflection by peasants to find solutions to their problems based on their own knowledge and external input.

Disproving Manuela de Almeida Callou's (2010: 7) observation that in Proderith "there was no real concern in teaching peasant communities to manage video as a means of communication for their own development," the scr The aim was to create the conditions for the farmers themselves to produce their own video materials in the regional communication units, with farmer technicians trained by the scr and where there was production and post-production capacity.

Between 1978 and 1996, the scr Proderith supported the organization of 49,500 producers in the humid tropics into 18 civil associations; produced 629 video programs (in 1981 the scr made one hundred videos; Fraser and Restrepo, 1996); helped elaborate 106 local development plans; trained 76 communication committees with farmers; installed and trained the staff of 13 local and five regional communication units; designed 314 graphic units, with a distribution of 32 650 copies; helped broadcast 1 519 local radio broadcasts and carried out a total of 16 418 "application sessions" with the attendance of 386 500 farmers (Murillo and Martinez, 2010: 219).3

Beginning in the 1990s in the imta began to carry out several projects based on the same methodology of communication for development, always with the nodal point of what is now called "advocacy", which at that time meant working together with peasant social groups, especially following the guidelines they gave and doing arduous mediation work between the hydraulic and environmental institutions and the local populations. We worked in more than nine states of the republic and served six regional communication units: five in the tropics: Zanapa-Tonalá, Tabasco; Center of Veracruz; Tizimín, Yucatán; Coast of Chiapas; Tamuín-Pujal Coy iiSan Luis Potosí; and one in the northwest: Ciudad Obregón, Sonora, as well as in several irrigation districts in particular. "In 1995, there were 13 local communication units in operation in Proderith project areas throughout the country, and there were 76 communication committees" (Fraser and Restrepo, 1996: 50).

Several directors of the imta (and several officials of the cna) had little understanding of the purpose and role of this area of communication, since, focused on the formula of social communication, they tended to equate it with institutional dissemination without recognizing the approaches of communication for social change, communication for development or rural communication. One pair of authors concludes that "The main weakness of the Communication System lies in the management aspects and in the impossibility of institutionalizing it as part of a national rural development policy" (Fraser and Restrepo, 1996: 97).

Retrospection (or what is known as flashback): the mysterious shoebox that holds part of a collective memory

The Communication Subcoordination of the imta4 had its offices (called the Central Level, at the scr) in Jiutepec, Morelos, where he settled in 1990. It occupied the first floor of a building: half of it was offices and the other half was the production and post-production area and the warehouse with the audiovisual equipment. There I found a shoebox with photographs, first stored and then rescued by Elizabeth Peña Montiel, the technician who was in charge of controlling the video library and recording all the "application session reports". She had kept it and showed it to me in 2011, approximately. In the box there were color photographs, some in black and white and also slides. I took some almost at random, digitized them and returned them to her. Before I resigned from the imtaIn 2012, I went back to the warehouse to go through the memory shoebox and was able to recover more than a dozen black and white and three color photographs, some of them a bit battered. I knew that no one was going to take care of retrieving the memory of the scrThe Communication Sub-Coordination was turned into a diffusion department, before becoming nothing more than a department...

In the mid-1990s, for example, the staff of the scr at the central level had been reduced by half, that is, to 20 people (Fraser and Restrepo, 1996); by the 2010s there were less than ten people and around 2022 only three specialists at most remained. Between 2012 and 2013, the oral archive that I had created and directed in the imtaThe video library, from 1996 to 2005, had been thrown in the trash, with folders of transcriptions, descriptions of each project and the audio tapes (audiocassettes). The video library, with more than 1,200 titles, is in danger of disappearing, given the lack of interest from the authorities of the imta in the period from 2018 to 2024. It is a pity that the audiovisual memory of Mexico's hydro-agricultural sector since 1978 is lost because in that video library there are not only finished programs, but hundreds of hours of audiovisual records in various formats (¾ inch Umatic, video 8, Hi8, etc.) that give an account of the history of hydro-agricultural development, peasant testimonies and many other topics.

The fact of finding photographs in a shoebox is similar to the one described by Zeyda Rodríguez (2012), although in her case they were postcards and the process of affectivity, according to the author, was in the messages written on the back of them. In my case, the affectivity was in my own knowledge of the content, of the places and of some of the people who appeared there: I had been hired by the fao to participate in the scr in 1990 and my first fieldwork had been in a town in Las Huastecas: Tamuín.

Of the photos recovered, I was able to digitize 59 in color; the originals were printed on matte and glossy paper; 19 in black and white, postcard size, printed on matte paper, as well as eight slides. In addition, I recovered 15 printed photographs of various sizes (from 20.2 x 12.2 cm to 34.5 x 26.4 cm), some on matte paper and others on glossy paper, and three color photographs, postcard size; 101 photographs in various formats, digitized. Thus, it is a minuscule contribution to the recovery of the graphic memory of the scr. Perhaps these photographs do not resonate in a larger scope and it may be a reverberation of the collective memory and a personal debt for being me the depositary of that little piece of memory, but it is also an opportunity to update knowledge and not let that experience of rural development, of an alternative communication, be totally lost. In any case, it is also a pretext to present a method that can be useful for scholars related to audiovisual research.

Why had these photographs been abandoned in a box? Were they ever used? Were they the ones that had been discarded? Were they print proofs, perhaps, the black and white ones? Impossible to know, who had taken them? As Peter Burke (2005: 236) mentions, in the case of some photographs, "Their testimony is especially valuable when texts are scarce or fragile". Therefore, we can think of these photographs as testimonial, although, as the same author states, they may not have been produced with that intention. We can imagine why such photographs were taken, but we cannot be sure if it was a personal exercise or a planned, defined and explicitly commissioned image survey by an institution. Many of the photographs seem to reflect the work that was being done at Proderith, but perhaps they responded to a personal impulse of the participants in each project to record certain events. One thing that is clear to me is that this was not an ethnophotographic record or an audiovisual anthropological practice. These are testimonial photographs. From the position of the viewer of the photograph, there is the feeling that it is "the testimony that what I see has been" (Barthes, 2022: 95).

Following Burke, the production of a photograph does not have to have the intentionality of being a visual testimony, although it can be interpreted as such. And therein lies the problem: how to read it? Although there have been a number of authors who share their techniques and methodologies of interpretation (many based on semiotics), in this text I want to present a methodology created step by step.

Some authors emphasize the importance of context, but this can be described with certain limitations: one of them, for example, is "the intended function of the image" (Burke, 2005: 239), which, in my opinion, is impossible to know reliably, to use the same terms of that author. In terms of "reliability", I am not convinced by the issue that "The testimony of a series of images is more reliable than that of an individual image" (Burke, 2005: 239), because a single image can give an element to contrast a photographic discourse that pretends to grant images a single meaning or unequivocal significance, or a discourse or narrative managed through a series of photographs. The problem of reliability, like that of veracity and verisimilitude, is simply not addressed in this article.

The interesting thing about these images, taken as a testimonial document, is that they are composed of different data (Muñoz, 2021): some are found within the image itself, others in the metadata and others outside the image. In this sense, the data is created and it is, precisely, by a gradual approach that is built, read and interpreted and that, in this case, has to do with the narrative sequence or "to turn a story into a scene" (Burke, 2005: 191), as it applies in the case of some of the photographs that are the object of the analysis that I present.

Almost none of the photographs found in the box have more information than the image itself, i.e., there is no "metadata" that would allow us to recognize which places they are from, on what dates they were taken or by whom.5 In this case, the photos must tell their own story and be interpreted and classified according to the knowledge of the Proderith. If an external researcher were directly confronted with them, it would be very difficult to explain them beyond the visual elements that appear there; therefore, knowledge of the context is important. In addition, I was able to consult some people who had been involved in the events photographed there: these people were communicologists or anthropologists who had participated in the Proderith. It is very true what Roland Barthes points out: "the reading of photography is always historical; it depends on the 'knowledge' of the reader, just as if it were a true language, which is only intelligible to those who learn its signs" (Barthes, 1986: 24). I also turned to other sources, such as some of the videos produced by the imtaI was able to cross-reference certain information that allowed me to gain a better understanding of some of the photographs by recognizing places, people, acquiring names and, in some cases, dates. I also made a documentary review, in which activities and dates are mentioned that were important to define the data that I will present below.

Regarding the method to interpret a photographic corpus that I propose, I can agree with what other authors suggest, such as denotative and connotative reading (Corona, 2012; Del Valle, 1993). In the case of the method proposed by Felix del Valle, he suggests following the "Lasswell paradigm" which, in my opinion, is not adequate. Harold D. Lasswell referred to a mass communication process in which the important thing was to answer the following long compound question: "Who says what to whom, under what circumstances, through what medium, for what purpose and with what effect?" (Lasswell, 1985). Félix del Valle is mistaken when he tries to equate this communication scheme to five questions: who, what, how, when, where, which are essential to elaborate a news article, as we know from studying journalism, but which have nothing to do with Lasswell's communicative process.

More interesting is the method followed by Sarah Corona, who, in addition to the connotative and denotative levels, introduces the dialogic level, that is, "in identifying the dialogue with other iconic and non-iconic discourses, which make the photograph intelligible" (Corona, 2012: 54), which is precisely what I have done when searching for information in documents, oral testimonies, videographic materials and my own memory. Due to the space of this article, the denotative level is mentioned in a general way and I have preferred to show how I created my own method, based on the experience lived in the systematization, classification and identification of photographs and photographic series: "In this way, the work of analysis is a kind of guessing game that involves discovering the discourses present in the photograph and tracing their relationships" (Corona, 2012: 62).

In principle, my knowledge and participation in the scr gave me clues to classify, describe and interpret the photographic content. So the method with which I began to work this photographic corpus was guided by abduction. Since I did not know the specific dates and places, I gave up classifying them in that way and started a grouping game that privileged the observation of technological modernization in the communicative instruments. I soon abandoned that path because there were photographs that did not contain any data in that sense. I concluded that it would be best to make a classification by generic activities observed, but there were also some other images that deserved a classification according to their specific context and that I identified: for example, a series of photographs that belonged to the same event. So I grouped some of them in that way.

I also identified a series of photographs that could be interpreted as a sequence. When I opened my perception and stopped thinking of the photo as individual data and turned it into a "statement", that is to say, into a set of greater significance, I was able to find that some photographs belonged to a temporal sequence in places located in the same region. Thus, from the collection of 101 images, I will bring here a corpus of 51 photographs, plus an external one, whose importance I will explain later.

Photographs classified as "field work".

The first group of photographs I classified as the field work of the scr in the Proderith. It consists of 22 digitized color photographs, whose authors are unknown. Based on the content of the photographs and the people who appear in them, they were taken between 1980 and 1990. Thirteen of these images are easily identifiable as to the place or the Proderith project where they were taken due to several elements that appear there.

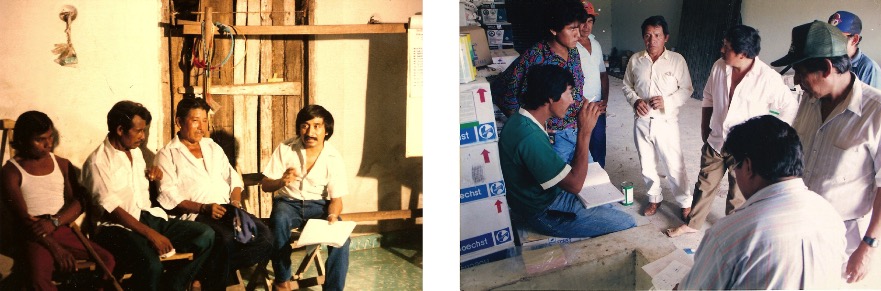

Image 1 shows four men, seated. The one on the right is Dionisio Amado Bobadilla, a communications technician in the Oriente de Yucatán project, who began working at Proderith in 1981. Almost out of the frame, on the far right, you can see part of a flip chart, one of the first tools used in Proderith. scr. I do not know the exact year and place where the photograph was taken, but it had to be between 1981 and 1989. One of the approaches to rural communication was that technology would not necessarily replace the contact and dialogue between the communication technician, the agricultural technician (or livestock farmer or health personnel) and the farmers. Sometimes the meetings with the farmers had a low technological presence, as we see in this first and a second photograph. Image 2 also shows Amado Bobadilla, in the center in a green shirt, talking with a group of farmers. It is not possible to locate the exact place or date either.

Image 3 was also taken in eastern Yucatán, a place identified by the traditional dress of some of the ladies in it. It appears to be a meeting with a technician, recognizable by the red and white cap, wristwatch and shoes, in a field where slash and burn, the Yucatecan milpa system, is practiced. Image 4 shows a meeting with members of the Sociedad Cooperativa U Yich Lakin, by the logo painted on a wall. Proderith began working with this cooperative in 1989, so this photograph may well be from that year.

I identify the following images as part of the Pujal Coy project iiwhich was served by the Tamuín Regional Communication Unit (ucrt), because I had worked in the region, and I was able to recognize some of the people in the photos and, also, I was able to make a comparison with images from some videos produced by the scr: El sonido local: una experiencia de comunicación ruralfrom 1992, which can be consulted here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spmTPQM-sGI and La Unidad de Comunicación Rural Tamuínundated, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=po7XrIOpSWw. The ucrt was in the town and municipality of the same name, Tamuín, in the northwest of San Luis Potosí; but there were local units and communication committees in several neighboring towns, such as Santa Marta, Aurelio Manrique or La Ceiba, among others.

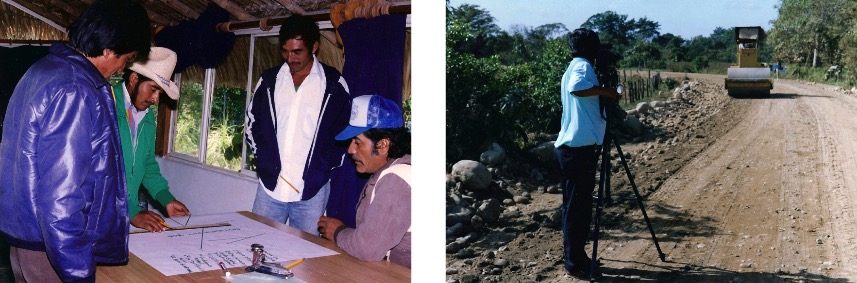

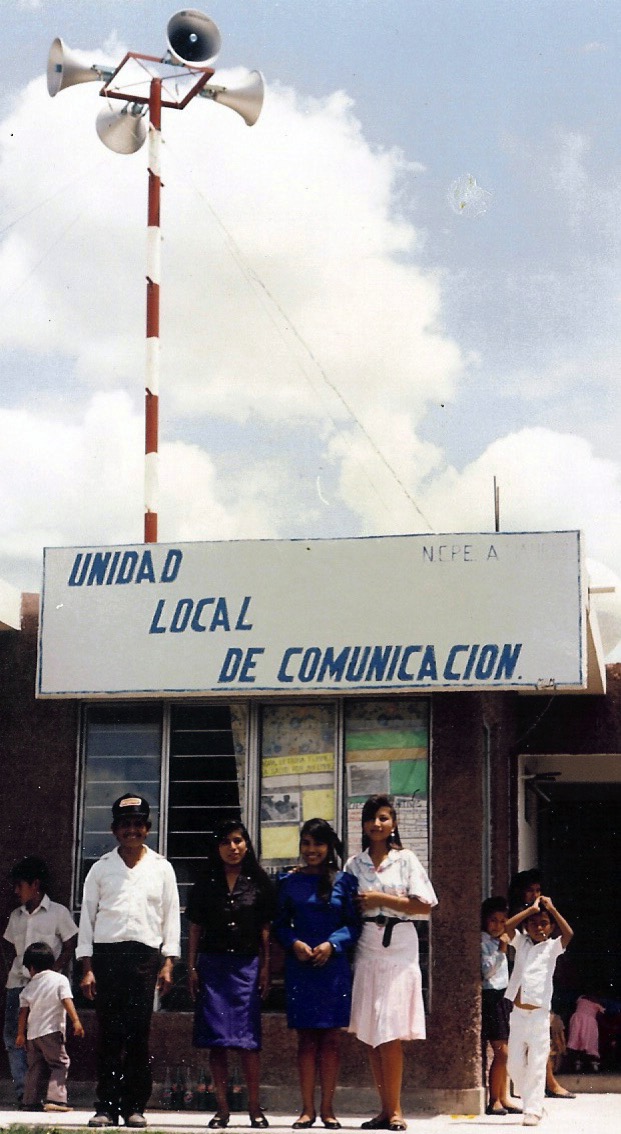

Image 5 shows the palapa and the sound system installed in the village of Santa Marta, where there was a communication committee. The palapa was the local meeting point and was built between 1989 and 1990; it was the first Local Communication Unit installed in Pujal Coy. iiThe community christened this covered meeting area as a the palapaand they proudly refer to it as the Cultural Palapa. And thus were born the Local Communication Units (ulc), which group several communication committees under one roof in the community (Fraser and Restrepo, 1996: 49).

Omar Fonseca, an anthropologist from the scr who was in charge of the Pujal Coy Project iiThe latter informs me that on that day there was a visit from an official of the fao on the occasion of the celebration of the work of the ladies of Santa Marta and an exhibition of photos of members of the Communication Committee. He sent me some other photographs he recorded of that activity (Fonseca, personal communication, September 3, 2024).

Image 6 shows a group of farmers using flipchart paper, possibly preparing a presentation during one of the workshops held. The place is the interior of the ucrt. This photograph can be dated between 1988 and 1990, since the unit was completed on June 1, 1988, in a former meteorological station that belonged to the sarh (Fraser and Restrepo, 1996). There were several workshops for the formation of local communication committees (on August 1, 1988, September-December 1988, April and May 1989) and intensive audiovisual production courses, such as the one held in May 1990 (Fraser and Nieves, 1992), among others that followed (Fraser and Nieves, 1992).

Image 7 shows a member of the ucrt making a camera, while a road is being built. I recognized the peasant technician who was operating the camera (unfortunately I don't remember his name) and that is why I was able to place him in the context of the Pujal Coy project. iiThis image was taken in the early 1990s, when this technician was working at the ucrt.

Images 8 and 9 show a training workshop on "application sessions", that is, a meeting in which a limited group of people participated; during the session, participants were given a "cartilla" or consultation booklet and a video was shown, with the purpose of commenting on it and reaching collective agreements. The open palapa was next to the ucrt. We can see that the equipment used was a wooden box with a television, a video player and both were connected to a car battery in the absence of light. The equipment that appears there was used until before 1990 (as we will see in the next group of images, in which the technological evolution in the application equipment will be discussed), so we can place the date of both between 1988 or 1989. In image 8, the woman standing, dressed in blue, is precisely Elizabeth Peña, who showed me the box of photographs. The seated woman, wearing a purple sweater, almost in the center of the photo, was a technique from the ucrtMarta Abundis. On the desks of the participants can be seen the "cartillas", with yellow covers, which contained complementary information to that which appeared in the video.

We can place image 9 in the Pujal Coy project. ii by comparing several elements with 8: the construction that appears there, i.e., the open palapa of the ucrtThe three people who appear in the photo also appear in image 8, seated at the desks. The person in the center of the photo, wearing a cap, appears without a jacket in image 8. Because of the equipment used and, by crossing the information with some dates of this type of workshops held, I am inclined to think that it is the one that took place in April and May 1989 (Fraser and Nieves, 1992). This is corroborated by the fact that in both photographs, attached to the wall, there is a wooden cabinet with a quarry filter, a technology for clean water consumption that was promoted in Pujal Coy. ii through video materials, the first of which was produced in 1989.6

Images 10 and 11 show the installation of a sound system in colonia 18 de Marzo, in the municipality of Rosamorada, Nayarit. The project was known as El Bejuco. It is a mini-sequence, in which a pole with a sound device is installed on the roof of the ejidal police station. In Proderith, the projects that were systematized the most and for which there is more information were those of Pujal Coy. ii and Oriente de Yucatán, of the others there is very little recoverable information. The only piece of information I have to locate the temporality of these photos is the poster that appears in a booth, in image 11, where it is shown that Ernesto Zedillo was a candidate for the presidency. That is why the photographic sequence can be placed in 1994. The red pickup truck with a booth that appears in image 10 was used to do field work in Proderith projects and has the first Proderith logo. imta and the sarh.7

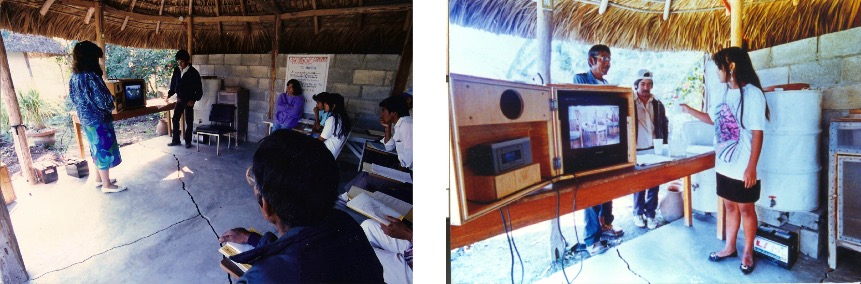

I could not identify the places where the following images were taken. In them you can see the evolution of the equipment used to transmit videos. Images 12, 13 and 17 show the boxes that were originally designed to transport a television, a VCR, a power plant and the necessary cables. These boxes, which weighed between 60 and 70 kilos, were known as "Beta Modules"; in an interview with a communications technician, he expressed himself about them as follows: "So he had to take out all his boxes, a cajota like a magician, he would take out his video, his switch, his cables, his cassette, or even batteries, he would take out of his boxes" (interview with Amado Bobadilla, intervention by José Luis Meléndez, central level communication technician, Tizimín, April 17, 1996). Below I will make some comments about each image.

Image 12 has a square format, different from the others, which are postcard size. According to the above, it must have been taken in the 1980s. Leaning on a pole, almost at the front of the meeting and at the height of the girl who operates the application module, is a communication technician from the scr central level, Lázaro Cano. I had the good fortune to contact him, send him the photograph and ask him to tell me what it evoked in him. In addition to determining the exact place and year, to my good fortune Lazaro turned out to be a very good rememberer, since his answer was the following:

This is an application session in an ejido in the immediate expansion area of the Tantoán-Santa Clara project,8 in the Magdaleno Aguilar ejido, the year is 1984. The session is conducted by a young girl recruited by the project. fao and the Unión de Ejidos Camino a la Liberación del Campesino. I hope you find the information useful [...] Beginnings of the activities of the Regional Communication Unit, too. The young woman was part of the Local Communication Unit of the Magdaleno Aguilar ejido. As the village did not have electricity, the module worked with a power plant, which had to be far from the place (25 to 30 meters) so that [the] noise would not interfere with the video [...] This photo marks the change from black and white to color as far as the applications are concerned; another change is in the sense that the power plant is no longer used and the application module is powered by a 12 vcd which, by means of a current inverter, is changed to ca 110 V; thus, the weight of the module is reduced from 50-60 kg to approximately 25-30 kg (Lázaro Cano, personal communication, June 20, 2024).

It was very common, when application sessions were held, for children to come and watch the "cinito" or the "tele". On several occasions during the fieldwork, the children would sit in the front row (see image 13). Also here we see the use of the battery for the energy that powers the equipment and the size of the box.

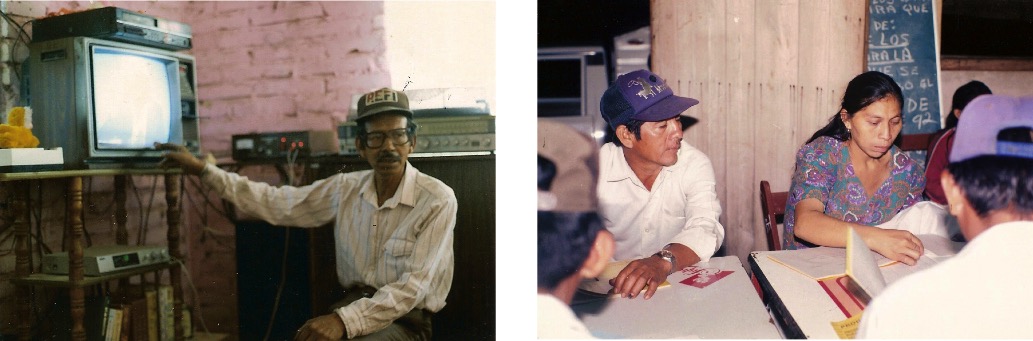

Image 14 was taken inside a home or office. The application modules do not appear, but a VCR, a TV set and, underneath, a sound amplifier connected to another device, behind the subject that appears in this one. Next to this device is a record player. Perhaps it could be a local communication unit, but there is no further information.

In image 15 I am inclined to think that it is a training course for communication committees, due to the closed room with several materials on the tables. According to a communication technician, José Luis Meléndez, these modules were called "2000" and began to be used in 1990 (interview with Amado Bobadilla, intervention by José Luis Meléndez, central level communication technician, Tizimín, April 17, 1996).

Due to the closed plan of this image, there is not much information that can place us in times and places. By the phenotype of the two main characters that appear turning their faces three quarters, a man and a woman, it could be thought that they are Mayan, which would place the photograph within the group of Oriente de Yucatán, although it can also be a speculation.

Image 16 was taken in an application session. It was most likely captured in the first half of the 1980s, by the Beta Module that appears, if we take into account the information provided by Lázaro Cano about the change and lightening of the application modules.

We can deduce that image 17 was taken between 1990 and 1994 by the team that appears there and that it is an application session. The 1994 date is because the second stage of Proderith concluded that year.

The so-called Beta Modules were used until 1990 (with the modifications incorporated in 1984, as we have seen), when the 2000 Modules were built, which were already lighter and used a video cassette recorder 8, making them more transportable as they weighed 30 kilos. With this information we can conclude that images 12 and 16 correspond to the 1980s, while 13 and 17 correspond to the 1990s.

Image 18 shows one of the communication tools used in the meetings between technicians and farmers or in the application sessions: the flip chart. From the content of the handwritten page placed on the flip chart, it was a meeting in which the community projects were being reviewed and, from the information that appears there ("Electrification is carried out in 1992"), it is possible to know that the image was taken between 1992 and 1994, date in which the second stage of Proderith concluded. In this photo, below the handwritten page that appears to be read by a peasant, a map can be seen. The outline that can barely be seen resembles the figure of the area delimited as the Oriente de Yucatán project; however, there is no corroboration of this fact. In the photograph, with his back turned, there is a bald person in a blue shirt, who appears to be either an official or a technician; mere speculation.

The photographs classified as "The Tamuin Sequence": a reconstruction of facts

Another group of images that I was able to identify in terms of a specific place and the year in which they were taken has a peculiar characteristic: it is, rather than a set, a sequence recorded within the framework of the ucrt in the Pujal Coy project ii. As I reviewed it in more detail, I realized that it was not one sequence, but two. What united these two sequences was, among other elements, a photograph that I found in my own digital archive more or less by chance.

Out-of-sequence photography

There is a photograph that is not considered in the recovered corpus, since it did not belong to the material found in the box, but had come into my hands, already digitized, due to other circumstances.9 It is the classic image of the training group and the trainees in a workshop in the ucrt with an unspecified subject. I have not found references to this particular workshop in the documents reviewed and when I contacted and asked about this photo to two people who participated in it and who appear there, they did not remember the subject nor the exact date,10 only the year: 1992. Nine people also appear in one or two of the photographic sequences reviewed below, which indicates that the three events occurred in the same period of time, that is, in contiguous days, although the sequential or temporal order cannot be reconstructed from the photographs or from the information obtained. A fact, which is offered in the knowledge of the context, is that some people that appear in the images belonged to the scr Some of them had managerial responsibilities, which prevented them from being in the field for long periods of time.

From left to right, standing: Luis Masías (consultant fao), Alberto Troilo (consultant fao), two unidentified persons, Marieliana Montaner (consultant fao-imta), two unidentified persons, Rosy (with a child in her arms), María de Jesús (behind), a communications technician from the Venustiano Carranza ejido (see image 19), Jorge Martínez (Communications Coordinator of the imtaAndrés from the ejido Nueva Unión, Omar Fonseca (an anthropologist from imta); below: unidentified person, Aída Albert (national expert fao); behind her, Santiago Funes (coordinator of the projects fao), Luz Elena Vargas (technical secretary in the imta); behind her, Marta Abundis (communications technician for the ucrt), Ángeles Navarro (intern fao) and Ricardo (driver).11 The great absentee, but also present, the photographer (who, by the way, is unknown).

The conformation of two sequences

I identified 29 photographs that had affinity for several elements. First of all, because of the material support; then, because of the content: the people who appeared in them repeatedly; and because some color photographs were also taken in the same places and with the same people who appeared in the black and white ones and, in some cases, there were shots taken against the field. However, upon closer inspection, I learned that this group of images could be divided into two sequences: one referring to the town of Aurelio Manrique (an hour's drive from Tamuín) and the other to the town of La Ceiba (a 25-minute drive also from Tamuín). What is impossible to know, with the information contained in both sequences, is which occurred first and which later: they happened on different days, because of the clothing of the same people who appear in one or the other; both sequences are from 1992.

The first sequence: New Ejidal Population Center Aurelio Manrique

This sequence has 22 images that were taken by two different photographers. We can know this by the photographic support: two cameras used simultaneously in the same act, one with black and white film (twelve images) and the other with color film (ten images). In the images of this sequence only one person appears with a camera; in the 24, in color, we can observe Luis Masías, so he is the only author of which we have certainty; he registered the black and white photographs and appears taking one. We do not know the identity of the other photographer. A quick note on this: when I first saw the color photographs and showed them, someone (I don't remember who) from the scr told me that the photographer had been Omar Fonseca, which can be justified when reviewing image 19, out of sequence, in which he has a camera hanging from his neck; however, in image 20 he does not have the camera with him. Furthermore, Fonseca himself claims not to have taken them (personal communication, June 24, 2024). So who was the other photographer in this sequence?12 The images of the sequence alone do not reveal the identity of the second photographer. I will now present two accounts of the same sequence: the photographic and the written reconstruction.

The voice of images

With the aforementioned caveats, I present the complete sequence, in a hypothetical order, leaving the images to tell a story on their own.

An imagined reconstruction

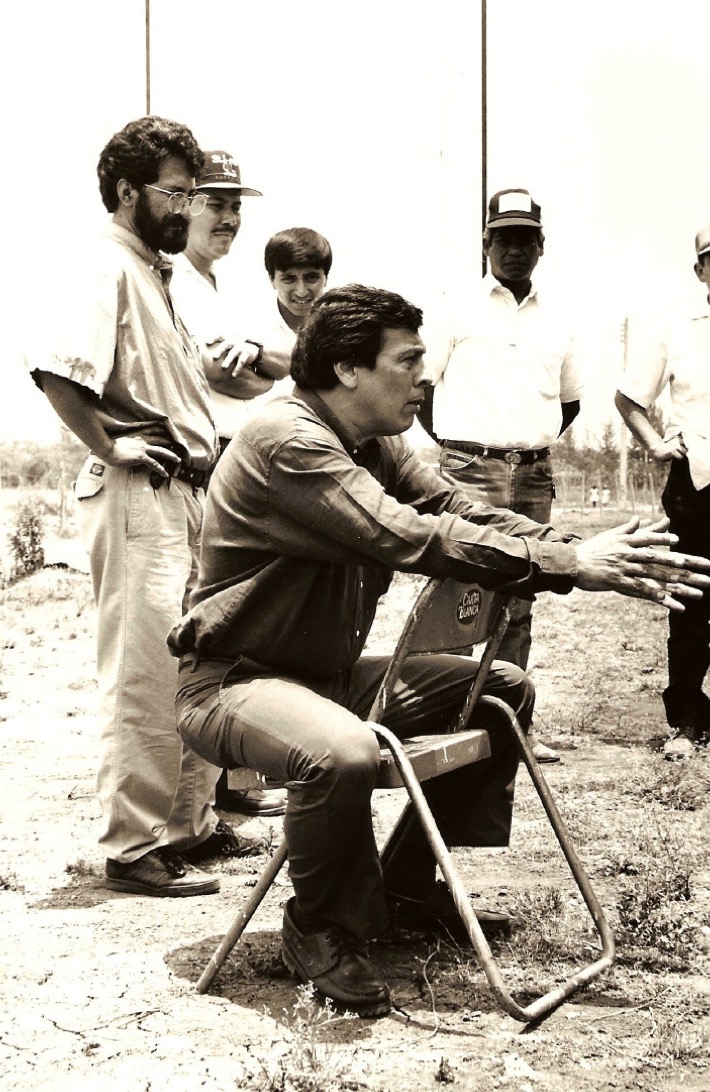

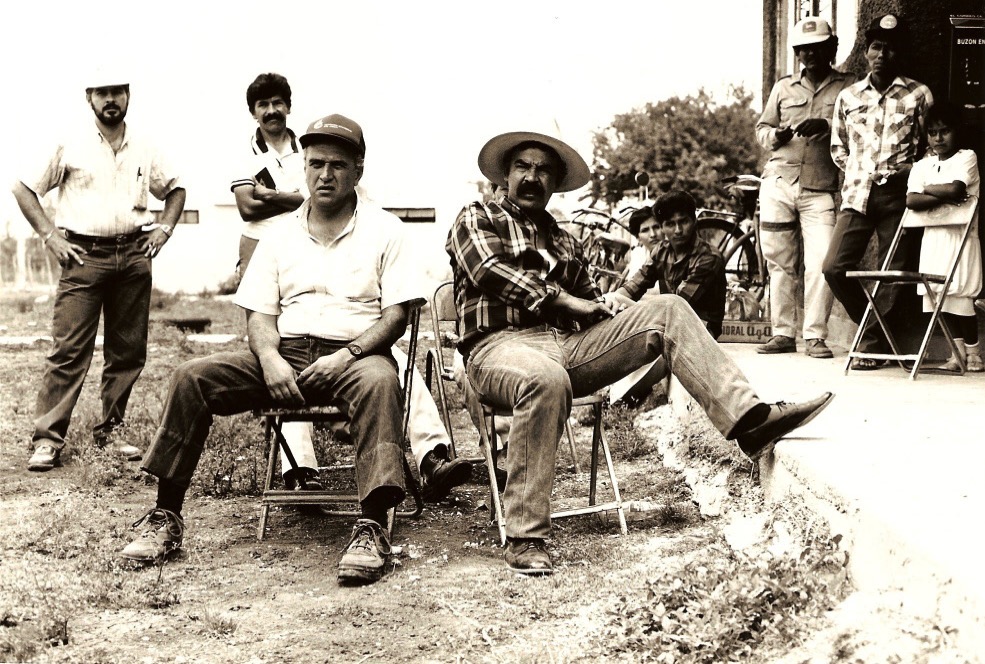

The story told by the photographs is very simple: the arrival at the Nuevo Centro de Población Ejidal Aurelio Manrique, in 1992, where the local unit was to be inaugurated, set up by the ucrt. The unit was equipped with application equipment and a local sound system. A few people arrived in a cart, among them the Communication Coordinator of the imtaJorge Martinez; the officer of the faoSantiago Funes; an executive of the National Water Commission (cna), Fernando Rueda Lujano, wearing a cap; behind them, a person whose identity is not distinguishable (image 20). There is a preliminary conversation (images 21 and 22) of the officer of the fao with the director of the Unión de Ejidos Camino a la Liberación del Campesino, Gabriel Anaya Fernández, with whom he had been working to promote Proderith in the Pujal Coy Project. ii and who is seated next to the engineer Rueda (image 22). In image 23 appear Martínez, Manuel Calvelo, Marta Abundis, Funes, Rueda and local people. In the back, in the background and standing, Luis Masías appears with his camera.

Afterwards, the inauguration ceremony begins, in which José Santiago, from the Local Communication Unit of Santa Marta (ejido of the Cultural Palapa), and next to him is Víctor Olguín, of the Aurelio Manrique Communication Committee. Among the attendees are people from the village, personnel from the imta and the faomembers of the ucrt and from the committee of the inaugurated unit, such as María del Carmen Fernández, who at the end of the event appears, with other young women and José Santiago, in front of the unit (image 28).

In José Santiago's speech, the leader of the Union de Ejidos and the officer of the faoFunes, who stand up and come to the front. The latter addresses a few words inside the unit, together with Marieliana Montaner and with the presence, above all, of women and children, who turn their backs to the windows of the unit (image 27). In image 25 there are two unidentified characters from image 19, who surely belonged to the fao and, near the door of the unit, Luz Elena Vargas. In the 26th, next to Santiago Funes, is Marieliana Montaner. All of them appear together in image 19 and that gives the clue to infer that the Tamuin sequences and that requested photo were taken at the same time. The event ends with the concentration of the attendees outside (image 28).13 and, later, a meal in a palapa, where the people of the village go. By the way, in some photos the audiovisual production equipment appears: in photo 29 there is a person with a microphone, in the foreground, and in photo 30, in the left margin and cropped (in blood), a tripod and a video camera can be seen.14 In that same photo, on the far left of the table, appears Epitacio Martínez, president of the Local Communication Unit of Santa Marta. So, could this story be told so simply? Is it an inconsequential event? In a larger context, in which photographs are witnesses with a voice of their own, they act in several dimensions: they prompt recollection, stir memory, recreate experiences and, in this case, also help to identify pieces of a puzzle of which there would be much more to tell.

Second Sequence: New Ejidal Population Center La Ceiba

This second sequence is made up of ten photographs, eight of them in black and white and two in color. From the information we have, we know that the author of the black and white photographs is Luis Masías. The place is the Nuevo Centro de Población Ejidal La Ceiba, close to the ucrt. I do not know if this sequence was before or after the previous one and the images do not tell us, but they indicate other things.

The voice of images

The reconstructed sequence is presented below through the images.

An imagined reconstruction

The visit to La Ceiba may have been part of a tour to show visiting officials where communication activities were taking place. The photos show how a roof is installed next to a house, how the representative from the fao and then, inside the tent, there is a meeting with the population and a table in front with the officials. In image 34 there is a figure with scissors and Funes taking a ribbon with a flower; it would seem that they are cutting an inaugural ribbon: if such hypothesis is correct, it would be the inauguration of the Local Communication Unit or of the Communication Committee of La Ceiba. The local units had equipment for reproduction of materials, not for production. In image 32, among the people, there is a person who had not appeared before (hence my provably false hypothesis that she was the photographer of the previous sequence, in color): I am referring to María Inés Roqué, who appears with a long skirt, between Marta Abundis and Marieliana Montaner, all three with their backs to the camera. She is also in front of image 31, with her back to the camera. Like the people in the imta and the fao appear with different clothing than in the previous sequence, I infer that this visit took place before or after that one. In image 34 there is a tripod and we can see a video camera; and in image 33, behind Funes, the technician of the ucrt (see image 7) with his head bent down, perhaps making a video and, on the right margin, part of the same microphone that appears in image 29. What is certain is that both sequences show the visit of officials to towns that belonged to the Pujal Coy project. ii and the warm welcome from the people of both towns. In local histories these photographs could make more sense: an event for the people of Aurelio Manrique and La Ceiba, the visit of officials and the inauguration of local communication units (if we accept the hypothesis I have given above). However, the question remains as to the author of the color photographs.

The method

When we work with images, a whole range of possibilities and ways of classifying, analyzing and interpreting are opened up. Here I have shown a particular method (without theoretical pretensions) that can help in the classification and interpretation of images. One aspect that must be taken into account when we have a corpus of images is that it is not enough to read each photograph in isolation, but to try to find sequences. Here I have tried some of them: sequences by places, by type of audiovisual technology, by characters and actions. Two factors facilitated the identification of places and dates: memory and personal experience, having participated in Proderith and having lived with many of the people who appear in the photographs, as well as the advantage of having been able to contact some of them. There is one more factor, not exclusive to this case I am presenting: the confrontation of sources. The consultation of videos and documents produced in the places and dates was substantial to obtain some elements that add to the description of these materials.

In a few words, what was the method I followed? We could say that this gazpacho soup (Raymundo Mier dixit) involved: a) meticulous observation of each photograph and as a whole; b) identification of people with their names, using my personal experience and my memory, since I worked with several of them and my first fieldwork, around 1990, was in the same area; c) identification of places, both by memory and by signs that appear in the photographs; d) comparison of sources: review of videos produced in those same years relating to the Pujal Coy project iiwhich can be found in the video library of the imta and are available through the Internet;15 e) ordering the photographic sequence and separating the materials; f) training the eye to identify sequences (photographic statements); g) consulting secondary sources, both documentary and videographic; h) direct consultation with some people who participated in the reference projects or who appeared in the images; i) reconstruction of the events captured in the photographic sequences, that is, observing the photos as narratives and seeking, in the data external to them, coherence to create a possible -or imagined- sequence of events. Something that I cannot omit is the search for the recovery of a memory that is dispersed, in which there are places, events and people that act, from time to time, as springs of memories, as that squeaky hinge that reminds you that it must be oiled.

Colophon

The names I have included throughout this article may not resonate with readers. However, in a process of collective memory and the recovery of actions within the framework of the scr In the Proderith project, it is important to recognize the people who appear in the groups of images and give them presence, as part of a collective experience of rural communication and to integrate a team in an effort that has been going on for decades. The exercise I propose in this paper can be a viable method for the interpretation of photographs from diverse archives and the objective has been to show how some pieces of the great puzzle of a collective memory can be put together, always through the images, the narrative sequences and the knowledge and imagination of the observer himself. And let's not forget: nostalgia. This article would probably not have been written without it.

Acknowledgments

An acknowledgment to all the colleagues who participated in the scr from the central level (and due to ignorance, for being from different periods and for not knowing many of them, I will surely omit some names): Jorge Martínez Ruiz, Santiago Everest Funes (†), Manuel Calvelo, Alejandro Aura (†), Luis Masías, José Luis Martínez Ruiz, Marieliana Montaner, José Luis Meléndez Vega (†), María Inés Roqué, Sergio Sanjinés, Edgar Valenzuela, Rafael Baraona (†), Pablo Ildefonso Chávez Hernández, Humberto Luna, Mercedes Escamilla Alcocer, Lázaro Cano Bravo, Francisco Carrillo Ramírez (†), Omar Fonseca Moreno, Roberto Menéndez Frione, Georgina Avilés, Claudia Espinosa García, Fernando Leyva Calvillo, Alberto Troilo, Arnoldo "el Gaucho" Korenfeld (†), Hermenegildo Alejandro Cisneros (†), Luz Elena Vargas Suárez, Carlos Peña Montiel, Elizabeth Peña Montiel, Arturo Nava Ayala, Arturo Brizuela Mundo, Aída Albert, Esther Padilla Calderón, Bernardo Ávila, Guillermo Hernández, Marco Antonio Sánchez Izquierdo, Emilio Cantón, Marisa López Santibáñez, Ricardo Ávila Ponce, Joel García Olvera, Gemma Cristina Millán Malo, Carmen Salazar, Marcos Estrada, Mónica Gutiérrez Garduño, Jaime Suaste Aguirre. Some ephemeral: Elías Levin, Juan Gabriel Sanz, Salvador Ávila, Javier Corona, Laura Martínez, Ángeles Navarro, Marcos Miranda, Héctor Sandoval Sabido.

Bibliography

Burke, Peter (2005). Visto y no visto. El uso de la imagen como documento histórico. Barcelona: Crítica.

Barthes, Roland (1986). Lo obvio y lo obtuso. Imágenes, gestos, voces. Barcelona: Paidós.

— (2022). La cámara lúcida. Nota sobre la fotografía. Ciudad de México: Paidós.

Calvelo Ríos, J. Manuel (1998). “La pedagogía masiva multimedial”, Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, vol. xxviii, núm. 4, pp. 197-205.

— (2013). “Comentarios sobre los modelos y la práctica de comunicación para el desarrollo”, en Carmen Castillo Rocha, Daniel Murillo Licea y Roxana Quiroz Carranza (eds.). Comunicación y desarrollo en la agenda latinoamericana del siglo xxi. Fundamentos teórico-filosóficos. Mérida: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, pp. 85-118.

Corona Berkin, Sarah (2012). “Guía para el análisis visual del sujeto político. La fotografía étnica”, en Sarah Corona Berkin (coord.). Pura imagen. México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, pp. 48-66.

De Almeida Callou, Manuela Rau (2010). “El proyecto Proderith: un caso de comunicación para el desarrollo participativo”. Congreso Euro-Iberoamericano de Alfabetización Mediática y Culturas Digitales. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla.

Del Valle Gastaminza, Félix (1993). “El análisis documental de la fotografía”, Cuadernos de Comunicación Multimedia, vol. 2, pp. 33-43.

Food and Agricultural Organization (2009). La fao en México. Más de 60 años de cooperación. 1945-2009. México: fao.

Fraser, Colin y Nieves Martínez (1992). Transferencia de un sistema de comunicación a las organizaciones campesinas. Segundo estudio de caso del Sistema de Comunicación Rural para el Desarrollo del Trópico Húmedo de México. Roma: fao.

— y Sonia Restrepo Estrada (1996). Comunicación para el desarrollo rural en México en los buenos y en los malos tiempos. Roma: fao.

Gumucio-Dagrón, Alfonso (2001). Haciendo olas. Historias de comunicación participativa para el cambio social. Nueva York: The Rockefeller Foundation.

Lasswell, Harold D. (1985). “Estructura y función de la comunicación en la sociedad”, en Miquel Moragas Spá. Sociología de la comunicación de masas, t. ii. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

Muñoz-Jiménez, José (2021). “Fotografía documental y antropológica en la encrucijada del siglo xxi”, Revista Inclusiones, vol. 8, núm. especial, pp. 181-201.

Murillo Licea, Daniel y Jorge Martínez Ruiz (2010). “Comunicación para el desarrollo en México: reflexiones sobre una experiencia en el trópico húmedo”, Estudios sobre las Culturas Contemporáneas, vol. xvi, núm. 31, pp. 201-225.

Rodríguez Morales, Zeyda (2012). “La imagen de las mujeres en postales de la primera mitad del siglo xx en México y su relación con la identidad y la afectividad”, en Sarah Corona Berkin (coord.). Pura imagen. México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, pp. 225-264.

Filmography

imta (1992). El sonido local: una experiencia de comunicación rural. Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spmTPQM-sGI

— (s/f). La Unidad de Comunicación Rural Tamuín. Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=po7XrIOpSWw.

Fonseca Moreno, Omar (1989). Filtro de cantera. Unidad de Comunicación Rural Tamuín, imta (video de archivo).

Navarrete Pellicer, Sergio y Mariano Báez Landa (2023). Conferencia de Manuel Calvelo Ríos/Comunicación y cambio social. Seminario riav, 23 de febrero de 2023, ciesas. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pPCjSMwiw1Q&list=PLpB7rn4NTStqK3dNQA5O42Gxi8GPpq_Q6&index=15

Daniel Murillo Licea is a doctor in Social Sciences, communicologist, editor, writer and smoker. Since 1990 he has carried out projects related to social sciences and water; he has supported training processes for indigenous people in the use of community video, at the invitation of the unicef Guatemala, in 2015. He is a founding member (1996) of the Network of Social Researchers on Water (rissa) and participates in the Audio-Visual Research Network of the ciesas (riav). She currently coordinates the Permanent Seminar on Water and Culture and is responsible for the Water, Society, Culture and Environment line of the graduate program in Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. ciesas, cdmx. He conducts research on water, water policy and indigenous peoples and, together with Los Tlacuaches Eléctricos, is developing a research project on water and indigenous peoples. rock and social movements