Amare: a look at migration in the Costa Chica of Oaxaca from an ethnofiction perspective.

- Ana Isabel León Fernández

- ― see biodata

Amare: a look at migration in the Costa Chica of Oaxaca from an ethnofiction perspective.

Receipt: October 17, 2024

Acceptance: March 29, 2025

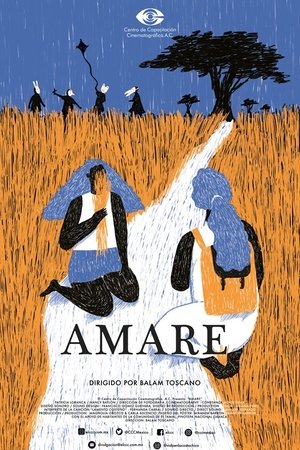

Amare

Balam Toscano2024 Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica A.C., Mexico.

Amare (2024) is a short fiction film by the Afro-Mexican filmmaker, native of the Oaxacan coast, Balam Benjamín Nieto Toscano, known for works such as Romina and Ivan (2021) y Mutsk Wuäjxtë’ (Pequeños zorros) (2024). Recently, Amare has been selected for the 28th edition of the Guanajuato International Film Festival.

His opera prima Soy Yuyé has just finished the post-production stage, so we will soon be able to enjoy it on screens. At the moment, the filmmaker is working on a new fiction film about the lives of seven teenage Afro-Costa Rican women who will show their yearnings and challenges in a territory marked by machismo and carnival.1 Toscano is a graduate of the Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica (Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica).ccc) and has received several awards and support.2

This review is focused on reflecting on the importance of ethnofiction cinema, made from within the communities.3 to make visible the issues and problems that concern them, such as, in this case, migration to the United States. My intention in recognizing Amare (2024) as a work of ethnofiction is to invite the public to see the film from different sensibilities offered by this work that navigates between the thin lines of documentary and fiction, bringing us closer to one of the realities of the Afro-descendant communities of the Oaxacan coast.

Without revealing too much of the plot, since the film is just beginning its exhibition route, the film tells us a story about women, art, migration and feelings narrated from the community of El Tamal, Santiago Pinotepa Nacional, Oaxaca. The main character is Amare, a woman from a coastal community in Oaxaca; the characters are mainly women, as the co-protagonist is her sister Cielo, followed by her mother and father, who is the figure on which the story is based, but not as the main character. Childhood is also present in the film.

The director opens and closes the film in a rounded manner, recovering real testimonies, first from the point of view of a mother and, at the end, from the point of view of a migrant woman. In the story, we see Cielo, a drawing teacher, who works enthusiastically with her students. Subsequently, we are presented with the conflict in the story: Cielo's father is very ill and asks for someone he wants to see; Cielo replies that he has not yet arrived, because he is far away. After the father's abrupt death, the protagonist of the story arrives in the community: Amare. Her arrival causes notable surprise, excitement and movement among the villagers.

It is after Amare's arrival when the themes that concern the characters are developed through the conversations between the sisters. The neuralgic point that Toscano presents us with is the constant migration of the inhabitants of the towns of the Costa Chica to the United States, mostly. Although in the film the motives are apparently economic, in reality the displacements can have other types of mitigating factors: persecution due to violence, social or ethnic stigmas.

The movie Amare has several virtues that are found at different levels that I would like to mention in order to propose some axes of reflection to the viewers, with the purpose of collaborating in the discussions and explorations after the viewing. First of all, it is remarkable the cultural belonging of the filmmaker Balam Toscano, who manages to reflect, with a look from the inside, not only the landscape characteristics of these towns with the great general shots he offers us, but also the slang, the daily customs, the rites and a kind of aesthetic experience of the life of the Costa Chiquense.

The film was shot in the community of El Tamal, Santiago Pinotepa Nacional, Oaxaca; an Afro-Mexican community with approximately 233 inhabitants. The cast of the film are not professional actors and actresses, but people from the same community who, in the words of the filmmaker, played themselves. Thus, the narrative of Amare has an authenticity that gives it an anthropological touch that can place it within the genre of ethnofiction.

AmareFrom the very first frame, it surprises those eyes accustomed to films shot with digital equipment. Being shot with a 35 mm camera, it offers another aspect on the screen, endowed with a beauty typical of the analog format. The director's decision to shoot in 35 mm can also be read as a kind of resistance to the technological demands of contemporary film production. It is enough to imagine the labor involved in transporting and caring for the rolls of film to the locations on the Costa Chica, because the weather conditions are hot and the distances are very long.

It seems pertinent to me to take into account, in the same way, the little access to this type of cinematographic equipment that Afro-Mexican peoples have had. In a more optimistic present, it seems that more and more young people who assume themselves as Afro-descendants are encouraged to pick up a camera and tell their own stories, although the digital format is the prevailing one in audiovisual works. Therefore, shooting a 35 mm film today can be seen as a symbolic reparation for those worthy and well-told stories that were never recorded for decades, due to the structural inequalities experienced by Afro-Mexican peoples.

Balam Benjamín Toscano is one of the few young people from his community who managed to emigrate to Mexico City to pursue higher education. This may seem an irrelevant fact, but for Afro-Mexican cinema it is not, since not many people from Afro-descendant communities in Mexico manage to get involved and develop in some area of the film circuit. The low presence of people from these territories is mostly due to structural factors: mainly the economic backwardness that has made it difficult for people to complete their high school education and to enroll in learning filmmaking.

Although Toscano always had a certain sensitivity for photography, he considers that the key moment in his career as an audiovisual filmmaker happened in 2016, when he was part of "Ambulante más allá".4 In a personal interview, he mentions how in that experience he learned, in an incipient way, to direct and photograph, but, above all, to "look" with greater sensitivity at what he wanted to tell. The Costa Rican filmmaker also emphasizes that most of his stories are based on Afro-descent and that this is perceived in the films in different "layers", ranging from the most obvious, such as the phenotype of the people, to other deeper layers such as socio-cultural or political issues.5

From my perspective, I consider Amare a work of ethnofiction, for let us remember that, on the one hand, ethnography is in charge of examining and recording specific and/or concrete sociocultural issues of peoples. In the audiovisual field, Paul Henley (2001) points out that ethnographic cinema has been a tool for anthropology, which, although it was born from the hand of the same discipline, regains strength from the eighties onwards when the interpretative twists enter a boom. In other words, the link between the interpretative paradigm and the capacity of ethnographic cinema to show "the particular" in cultures is reinforced (Henley, 2001: 25). Although ethnographic cinema is closely linked to anthropological work, and in this case we are not talking about a purely ethnographic work, but a cinematographic one, I highlight the film's capacity to show a reality with its social, cultural and territorial particularities, as well as the figure of the director Balam Toscano who, being a native of the place, "replaces" the figure of the anthropologist, who would need to do field work to make ethnographic cinema.

The imaginative component of the work that makes it an ethnofiction can be traced back to the cinema inaugurated by Jean Rouch and the current of the cinema-verité. Rouch's cinema managed to challenge the limits of the camera's place among the communities, as well as the lines between reality and fiction by presenting fictional stories, but with native people from the villages reflecting their longings, desires and subjectivities in the films (Salvetti, 2012).

Amare also dialogues with other films whose directors have dared to challenge the symbolic frontier between documentary (as a paradigm of the "real" in cinema) and fiction. Although it seems to me that the debate about the non-existent division between the two genres is a discussion that has already been overcome and I consider that Amare falls more into the category of ethnofiction., I would like to recover one of the most outstanding cases in the genealogy of the docufiction genre.6 in order to broaden the picture.

It was from video art that the first attempts to make films that amalgamate fiction with the everyday reality of people appeared. Such was the case of Sarah Minter, a pioneer of video art in Mexico in the 1980s. In the 1980s, the growth of the then Federal District and the poverty in its marginal neighborhoods became tangible. During this period, youth gangs were born in the peripheries, many of them made up of young people from indigenous peoples and impoverished peasant families. The most stereotyped group, because of their brazenness, were the punks. In this context, Minter ventured into the experimentation that amalgamates documentary and fiction, in his works No one is innocent (1985) y Punk soul (1991). His attempt was a personal narrative framed in the audiovisual language; he hoped for a playful complicity with the actors and to give an independent character to his production (Minter, 2008: 5).

It seems that for some social groups that have been more affected by the stereotypes created by hegemonic cinema, it is more important to break the reality-fiction dichotomy: breaking this binomial is a strategy to deepen their own representations in a more respectful and less prejudiced way. As a negatively stereotyped group, the punk youth of the 1980s serve as an example.

Maite Garbayo points out that in No one is innocent portrays the band Mierdas Punks from Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl. There, Minter met a member of the band and became interested in the life of the marginal groups of the city, far from the privileged and upper class youth. The neighborhood youths had a subaltern aesthetic. Their look reflects what it means to be chavo-banda. Minter, contrary to the media's belief, patents an image of chavo-banda away from drug use and criminal issues. Minter humanizes the punks, shows their links and their future. He embeds them in the framework of their marginalized conditions, although he does not make them part of it, but a consequence. Garbayo suggests that Minter "pacifies" the chavos-banda, since they were an object of repudiation and meant a threat to the government and the press (Garbayo, 2016: 83-84).

While the case of Sarah Minter and No one is innocent seems far removed from Amare, Since filmmaker Minter had an outside view of the community she represented on screen, the intention of evoking her in this review is also to situate a genealogy of the docufiction genre in cinema and its impact on the search to eliminate stereotypes and negative representations of certain population groups.

Again, the narrative of the films made from within the communities of the Costa Chica, the narrative of Amare is also reminiscent of the case of the feature film They made us overnight (2021)7 by Antonio Hernández. This film, officially classified as a documentary, shows part of the daily life of the Afro-Mestizo Salinas Tello family. In its narrative we see part of their customs and traditions in the coastal town of San Marquitos, founded in 1974, when Cyclone Dolores flooded the town of Charco Redondo and, displaced by the natural disaster, some of its inhabitants founded the community of San Marquitos. The "documentary" genre of They made us overnight seems more a formalism than something that defines the style of the film. While it is true that we see the daily life of the Salinas Tello family reflected in the script, there are fictional scenes that add other touches: either of freshness or "magical realism"; this does not detract from the veracity of its documentary style.

They made us overnight shows us part of the worldview of the Afro-Costa Rican peoples, such as the belief in the "tona", the "empacho" cures and the dance of the Diablos, which connects this existence with other planes on the days of the dead. He moves away from stereotypes coming from racism, recurrent in cinema, to tell, from his own point of view, who are the Salinas Tello and, therefore, who are the Afro-Mexican peoples of the Costa Chica.

In line with the above, it seems to me that Amare is inserted not only in the growing production of Afro-Mexican cinema, but also in a narrative of ethnofiction that finds its functionality in representing the peoples of Costa Rica from their realities, such as their customs and traditions, as well as their problems, such as the constant migration to the United States of America. It would seem that the resistance and the "cimarronaje" (the "cimarronaje")8 in cinema are also practiced in defiance of the formalisms of the film genres imposed by the industry. In this sense, Amare has a double anthropological value: on the one hand, the ethnographic merit of the film that somehow refers us "to an encounter with otherness that provokes in us, directly or indirectly, the fundamental concern that gives rise to the ethnographic experience" (Zirión, 2015: 13); and on the other hand, the genuine curiosity it awakens in specialists on the subject to follow the steps of these young Afro-Mexican filmmakers, such as Balam Toscano, and the expressive resources they make use of.

As an anthropologist working on the audiovisual theme in Costa Chica, I consider the relevance of Amare is, to say the least, outstanding. Beyond the plot and the knots that sustain the narrative, there are several issues worth mentioning that, in my opinion, give anthropological value to the fiction that the director has shown. In my fieldwork, I have witnessed that the problems addressed by Balam Toscano are of an everyday nature in the Afro-Mexican communities.

The first of these concerns education. In the peripheral populations of Pinotepa Nacional (specifically, but also in the entire Costa Chica, in general) there is a palpable governmental abandonment of education. Children tend to be abandoned by the Ministry of Public Education. As shown in AmareThe children are taught by people from the communities themselves. Such is the case of Corralero, where the filming took place. The negrada9 (2018) by Jorge Pérez Solano. In Corralero I was able to witness the initiative of a workshop leader to support the education of infants, who were neglected by their assigned teachers. And, in a case very similar to the one presented at AmareThe workshop leader, an expert in engraving, encouraged the creativity and imagination of her adopted students through the arts (in this case, painting). Balam Toscano brings us closer to a reality that is often minimized: students do not have the right tools to develop their individual talents; it is the intervention of third parties that manages to alleviate the educational lag.

The issue of children abandoned by their parents (as mentioned by Cielo and Amare in their final conversation) is also one of the social setbacks experienced in Costa Chica. In multiple interviews conducted for my research, my interlocutors were concerned about the phenomenon of youth homelessness. Due to migration issues, children are often neglected: parents who travel, often illegally, to the United States, leave their children behind, who, in the best of cases, are left in the care of their grandparents. However, many grow up unprotected and sometimes fall into a spiral that Balam Toscano briefly mentions in his film: drug trafficking and its derivatives.

Insecurity in Costa Chica is not something that can be ignored. Regardless of the situations that are common to all regions of the country (neighborhood conflicts, accidents, domestic violence, etc.), the Afro-descendant communities suffer the incidence of drug trafficking. Organized crime takes advantage of abandoned children for its lucrative purposes: whether as clients or as members of their organization, recruited by force or out of necessity, the cartels pervert the young people of the area. In an interview with an activist from José María Morelos, she pointed out to me the growing number of adolescents integrated into the criminal spirals: from an early age they are induced to consume narcotics; later they are forced to be part of drug trafficking, with dangerous and poorly paid jobs.

The central issue, addressed by Balam Toscano, is undoubtedly migration. Amare is not only a traveler in search of better opportunities who returns and breaks with the family economy (as she can no longer provide money), but she becomes a fundamental agent in the dialogue about what it means to be a woman, black and immigrant. This triad of conditions tends to make people in Costa Chica vulnerable: women, in a socially machista country, are undervalued and delegated to domestic work; Afro-descendants have historically suffered from a racism that makes them invisible and disregards them from the Mexican State's national project; migrants and the population in transit are also undervalued and their rights are questioned. A combination of these factors occurs in cases where Afro-Mexicans are confused with South American migrants and are foreignized through the racist premise that there are no Afro-descendants in Mexico.

Minor, but equally important, are those concerning the cosmovision of the peoples of African origin. Talking to the Ceiba tree is an ancestral tradition, even among the Maya, that allows the living to connect with their deceased relatives. The funeral rites of the father of Cielo and Amare are well represented. I make this assessment because one of my field incursions took place on the Day of the Dead. Based on participatory ethnography, I find that Balam Toscano's production contains vast real elements of the everyday life of Afro-Mexican communities. This is the strongest point of AmareDespite being a fiction, his filmic exposition is well-documented and reflects concrete realities in the Costa Chica, as are all the problems mentioned so far.

Finally, I would not want to leave aside the technical aspects of Amare. Visually, the cinematography is beautiful and well done. The pinnacle of it is the final shot, when the sisters Cielo and Amare talk on the shores of a small lake. The greenness of the surrounding nature contrasts with the arid landscapes of the Costa Chica at a certain time of the year. Perhaps Balam Toscano gave us this shot with the intention of demonstrating that the interlocution of the sisters was extremely natural: both gave opinions and spoke to each other with the truth that each one possessed. Cielo's recrimination to Amare for her estrangement, on the one hand; and Amare's desire to convince Cielo to migrate with her, on the other. The narrative, though short, is concise and allows viewers to reflect on what is exposed on screen.

In sum, Amare is an important product for Mexican cinematography for two crucial reasons: it gives an account of a concrete reality in towns forgotten by the majority of the inhabitants (in this case, the Afro-Mexican communities of the Costa Chica); and it is a continuation of the work of ethnofiction, with anthropological overtones, which is why I suggest categorizing Balam Toscano's film as ethnofiction. This proposal is due to the fact that it takes into account the daily life of the communities, which is narrated by one of its members. Undoubtedly, the ethnofiction genre is capable of bringing viewers closer to realities alien to them, with a powerful sensitivity and depth that would be worth rethinking if it is comparable to other film genres, as well as its scope and limitations.

Bibliography

Garbayo Maeztu, Maite (2016). “Intersubjetividad y transferencia: apuntes para la construcción de un caso de estudio”, Nierika. Revista de Estudios de Arte, año 5, núm. 9.

Henley, Paul (2001). “Cine etnográfico: tecnología, práctica y teoría antropológica”, Desacatos. Revista de Antropología Social. México: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, núm. 8, invierno, pp. 17-36.

Minter, Sarah (2008). “A vuelo de pájaro, el video en México: sus inicios y su contexto”, en Laura Baigorri (ed.). Video en Latinoamérica. Una historia crítica. Madrid: Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo.

Miranda Robles, Franklin (2011). “Cimarronaje cultural e identidad afrolatinoamericana. Reflexiones acerca de un proceso de autoidentificación heterogéneo”, Revista de la Casa de las Américas, núm. 264, pp. 39-56.

Salvetti, Vivina Perla (2017). “Identidad nativa en los filmes de Jean Rouch: ¿etno-ficción o etnon fiction?”. Buenos Aires: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Disponible en: https://www.academia.edu/32888324/Identidad_Nativa_en_los_filmes_de_Jean_Rouch_Etno_Ficci%C3%B3n_o_Etnon_fiction

Walker, Sheila S. (comp.) (2013). Conocimiento desde adentro. Los afrosudamericanos hablan de sus pueblos y sus historias. Fundación Pedro Andavérez Peralta/Afrodiáspora/Fundación Interamericana/Organización Católica Canadiense para el Desarrollo y la Paz.

Zirión, Antonio (2015). “Miradas cómplices: cine etnográfico, estrategias colaborativas y antropología visual aplicada”, Revista Iztapalapa. México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, vol. 36, núm. 78, pp. 45-56.

Filmography

Guzmán, Ximena y Balam Toscano (2024). Mutsk Wuäjxtë’ (Pequeños zorros). Cimarrón Audiovisual.

Hernández, Antonio (2021). Nos hicieron noche. Tangram Films, Ambulante, Detona.

Minter, Sarah (1985). Nadie es inocente. Independiente.

— (1991). Alma punk. Independiente.

Pérez Solano, Jorge (2018) La negrada. Tirisia Cine.

Toscano, Balam (2021). Romina e Iván. Cimarrón Audiovisual.

— (actualmente en etapa de posproducción). Soy Yuyé. Cimarrón Audiovisual.

Technical data sheet of Amare

Título: Amare

Año: 2024

País: México

Género: ficción; drama

Duración: 23 minutos

Formato: dcp, Color

Dirección: Balam Toscano

Dirección de Producción: Magnolia Orozco Osegueda, Carla Ascencio Barahona

Fotografía: Constanza Moctezuma

Guion: Balam Toscano

Edición: Balam Toscano

Sonido: Emanuel Gerardo Guerrero, Francisco Gómez Guevara

Diseño Sonoro: Francisco Gómez Guevara

Música original: Francisco Gómez Guevara, Constanza Moctezuma, Balam N. Toscano

Dirección de Arte: Ariana Pérez Martínez

Compañía productora: Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica, A.C.

Reparto: Nancy Bailón, Patricia Loranca, Nidia Ramos Hernandez, Heriberto Ángel Hernández, Isabel Dominga Hernández Ramos

Formato de Captura: 35 mm

Colorista: Constanza Moctezuma

Fecha de rodaje: febrero de 2023

Velocidad de proyección: 24 fps

Tema: Migración, identidad

Locaciones: El Tamal, Oaxaca

Ana Isabel León Fernández is a historical anthropologist from the Universidad Veracruzana; master's degree in Anthropological Sciences from the Universidad Veracruzana. uam-Iztapalapa. Her research topics include film audiences; film representations and identities in Mexico and Afro-Mexican peoples. She is also a cultural manager in the area of film exhibition with the Colectivo Cinema Colecta (Veracruz) since 2014; she collaborates in the programming area of the Festival Artístico Audiovisual Afrodescendencias. She is currently pursuing her doctoral studies at the Graduate Program in Anthropological Sciences at the University of Mexico. uam-Iztapalapa.