Between Sinophobia and Mythology, an essay on visual anthropology and social networks.

- Arturo Humberto Gutiérrez del Ángel

- ― see biodata

Between Sinophobia and Mythology, an essay on visual anthropology and social networks.

Receipt: April 29, 2024

Acceptance: November 12, 2024

Abstract

In this essay we seek to understand and analyze how mythological structures occupy a central place in sinophobic thought and how social networks operate as a vehicle for it. We use the tools of visual anthropology, which allow us to study these fields: the anthropological foundations of mythology and its expression in the form of memes, smashupsfilms and even songs. To achieve this end, digital ethnography occupied a preeminent place. Moreover, this type of thinking is triggered by social conditions. We will demonstrate how the sinophobic content in the smashups The social conditions, such as pandemics, are exacerbated by the presence of the Chinese.

Keywords: visual anthropology, meme, mythology, sinophobia, smashups

at the intersection of sinophobia and mythology: visual anthropology and social media

This essay analyzes the mythological structures at the core of Sinophobic beliefs and examines how social media channels this discourse. It employs tools from visual anthropology to analyze the anthropological underpinnings of mythology manifested in Sinophobic expressions such as memes, smashups, films, and even songs. Digital ethnography was critical to the analysis, which also reveals how social upheavals attributed to Chinese communities (pandemics, crises) exacerbate Sinophobic thinking. The investigation explores how the Sinophobic content in smashups intensifies in response to social circumstances.

Keywords: meme, visual anthropology, mythology, Sinophobia, smashups.

Introduction

Visual anthropology is a methodological tool that has not been fully explored, particularly in the study of social networks of digital origin: can social processes be revealed through this methodology? Due to its capacity to evidence semantic articulations through the multiple forms that the image acquires, we consider that the answer is positive, since it objectifies social facts by means of emotional criteria, positive and negative, that entail valuative criteria such as rage, racism, xenophobia, love or compassion. And in this sense, is it possible, through digital ethnography in social networks, to study this set of values?1 The answer is again positive. To do so, we will trace one of the emotional, economic and social structures that can have the greatest transcendence in cultures: sinophobia. We consider that, by means of the aforementioned methodology, it is possible to scrutinize a set of visual, sensory and sound expressions -mainly in the smashups2 and gifs3 of different social networks, such as, among others, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram or YouTube; considered as a new (semantic) type of writing that articulates and overflows the same fact of the letter and the word. A novel technology that uses for its own purposes the likes and comments. Undoubtedly, these expressions find a diachronic dialogue with graphic images from the thirties of the last century, but also with their close cousins, memes: is it possible to carry out fieldwork in social networks to discover, study and systematize attitudes of one human group towards another? The answer, which until recently the most conservative researchers considered impossible, changed after the development of Web 2.0, since it was accepted that social networks are also a set of plexuses in which ideologies, prejudices, rituals, myths and pathologies converge; the difficulty has been to systematize this information. Thus, the socioanthropological view on this phenomenon offers a fertile ethnographic field, where a set of relationships can be arranged through which we intend to build an ethnological model. Nevertheless, it is paradoxical that the speed with which networks change and become more dynamic, rapid, creative, expressive and expansive does not necessarily alter prejudices or racial stereotypes. Rather, they offer an ideological melting pot on certain cultural and historical stereotypes, which researchers such as Miguel Lisbona and Enrique Rodriguez (2018) or Sonia Valle de Frutos (2024) have made clear. However, a network analysis of these processes leads us to consider that we are faced with one of the most sophisticated expressions of mythological thinking that, as we shall see, also responds to, and can be explained, based on the laws of myth, articulating a virtual community that has resonance in the empirical world.

Mythological, visual anthropology and digital ethnography.

For Claude Levi-Strauss (1995), myth is language at a very deep level, which sinks its roots beyond the sensible world. Its discursive strategies do indeed draw on the empirical world, but its combinatory rules respond to another logic. Myth can be transmitted through speech, which Ferdinand de Saussure calls irreversible signifier (1985: 87-106); however, it goes beyond this and becomes concept, reversible meaning that seeks to emerge using the signifier for that purpose. We will see that this ahistorical (signifier) and historical (signified) pairing can help us understand sinophobia as a concept that changes its vehicle of expression, i.e., its signifier, to manifest itself as a permanent structure, in this case combined with the messages that the smashups want to emit. That is to say, the ahistorical-signifying/historical-signified polarity converted into language concentrated in myth, which distinguishes, as Lévi-Strauss announces: "the language and the speaks"according to the temporal systems to which one and the other refer. Now, myth is also defined by a temporal system that combines the properties of the other two. "A myth always refers to past events: 'before the creation of the world' or 'during the first ages' or in any case 'long ago'. But the intrinsic value attributed to myth comes from the fact that these events, which are supposed to have occurred at a moment in time, also form a permanent structure. It refers simultaneously to the past, the present and the future" (Lévi-Strauss, 1987: 231-232). Sinophobic thought fulfills these requirements to be called a mythical form of thought.

And although the myths studied by Lévi-Strauss belong to mostly Amerindian cultures, the method by which he approached them can be easily transferred to contemporary societies, as Umberto Eco (1999 [1968]: 31) or A. J. Greimas (1985 [1982]) did for film characters, since myth has no nationality, much less borders; it is part of the same social fact, like rituals or the dream world: can this theoretical approach be applied to the digital world? The answer is affirmative if we convert the characters of the smashups The difference with an actor lies in the fact that actants are bearers of a message that depends on a given structure that they convey, and can be mythological, cosmogonic, social, economic, or an eclectic set of motley categories. They become in themselves a narration whose purpose is to convey a message under given, aprioristic codes that are reanimated in each event. The actor needs a script, his performance is a given plan structured under the laws of "style".

We consider that the set of meanings of the actants is the expressive way and its formation depends on the following: (a) the necessary relations generated by units (equivalent to lexemes or predicates of mythological narrative elements), which operate in a succession of semantic statements whose function-predicates behave as sets pointing to an end; b) semantic statements are constituted by means of actantial properties that affirm an action, which leads to c) actants adopting a role of subjects-heroes, objects-values, sources or addressees, opponents or traitors, helpers of positive or negative forces, which depend on cultural values; so that d) society endows actants with categories that they symbolically absorb to signify the role they will abbreviate from their action. Their message thus depends on a structure that is in turn temporal as well as timeless, like myth (Greimas, [1985] 1982: 40). Can we apply this formula to the case of memes and smashups? Of course, and the enunciated methodology supports us in doing so. Obviously, if we raise the semiological formula of what Charles Sanders Peirce named indicia (Moore, 1972), that is, the concrete analysis of the concrete situation. That is, any iconography (smashups) is an object of meaning (Moore, 1972). And it is precisely this meaning that allows us to analyze visual anthropology. When we study concrete expressions in this article, we refer to the analysis of their visual forms as bearers of meaning. And what does ethnography do? Precisely, through participant observation, to find out this veiled, unconscious but indubitable semantic meaning of the cultural meanings of any social phenomenon. And it turns out that one of these contemporary manifestations are social networks. Therefore, methodologically speaking, the construction of the object of meaning to be studied must include this analysis emanating from the interpretation of what we will call a visual myth: that of sinophobia, elevated, for its study, to an iconography. As we shall see, digital ethnography on social networks allows us to understand the meanings of the smashups in its particular context.

The surface of Sinophobia

As we will see, through a barely superficial search in the networks, we discover that an ontological and mythical repetitive form (character of the myth and rite) of racial discrimination is exposed there, in this case sinophobic, increased as a crucible of the myth since the pandemic of covid-19. These criteria are repeated as stereotypes that constitute a discourse based on the biological and cultural differences that the networks expose as prejudices based on a priori criteria and value categories.

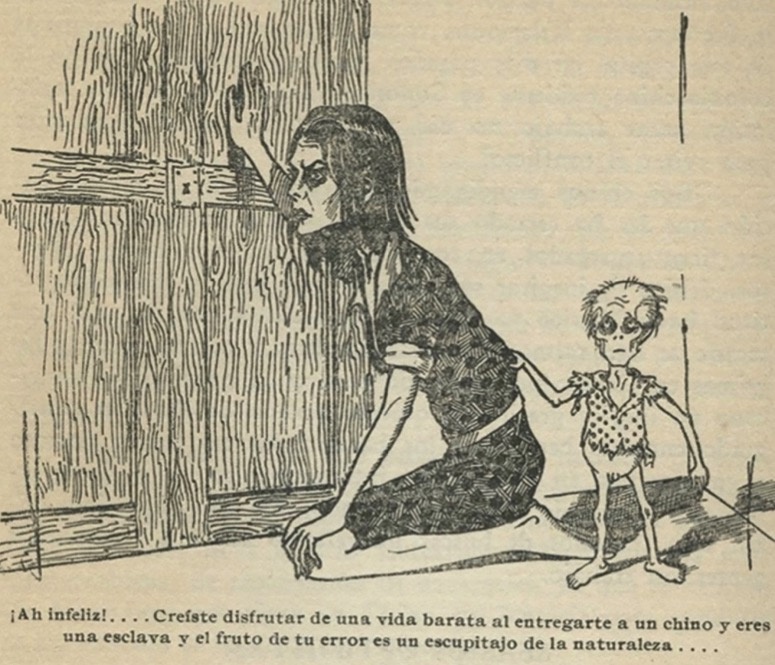

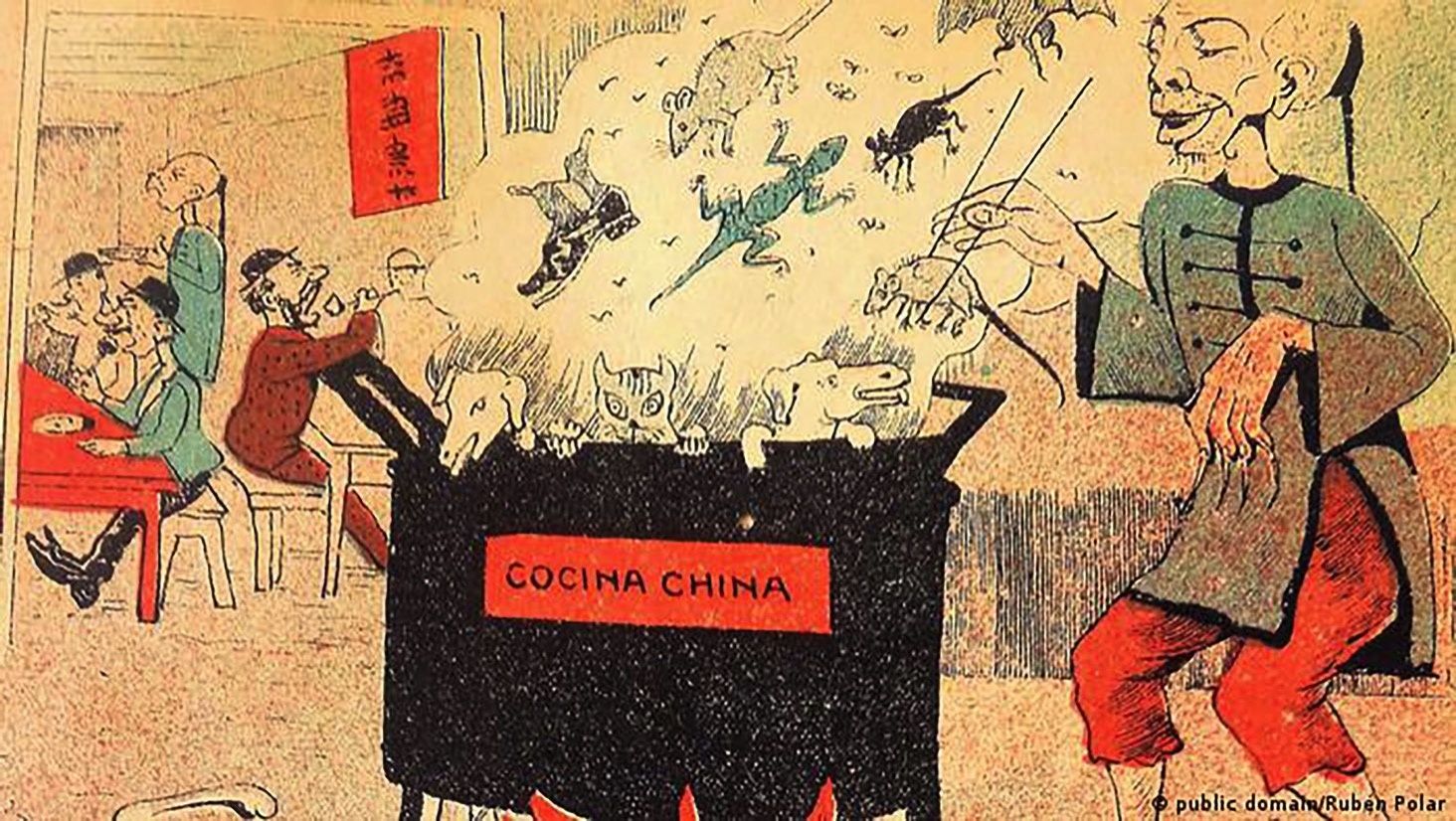

Now, our reflections are preceded by two works that use image analysis as a methodology to discover a set of relationships around the Chinese. One of them focuses on the reflection of digital ethnography with memes: Stereotypes about Chinese in Mexico: from caricatured image to Internet memeby Miguel Lisbona and Enrique Rodríguez (2018). The authors want to demonstrate the continuity of negative stereotypes that have surrounded the Chinese in Mexico. They suggest that technology allows interrogating the persistence of transformations about this group, while showing the changes that are incorporated with the tools provided. Through virtual ethnography they analyze several memes that allude to the racial character of the Chinese. To demonstrate this, they use the stereotypical construction of this group through historical drawings produced in the post-revolution period, which they compare with current memes. Thus, through this comparative, historical and ethnographic work, they show how sinophobic stereotypes are maintained, or transformed, depending also on the media through which they are disseminated. And although the authors do not pose this as a mythological device, it undoubtedly reproduces the myth of the dirty, dangerous, exogenous Chinese, that is, it underpins the foundational myth of the pure race, creole vs. outsider.

The other job is Chinese stories on the screen: filmic discourses of segregation, exclusion, integration and inclusion around Chinese communities in Mexico.by Rocío González de Arce (Gutiérrez and Alvarado, 2025), on the image of the Chinese in Mexican cinema. The author analyzes 63 films with characters depicting Chinese, but with Mexican actors; or Chinese with non-Chinese Asian actors, and in the least cases, Chinese. She finds that the cinematographic language about this group depends on the era and national politics. The characters that represent them are either excluded for being different and having strange customs, such as their food or dress; or they are included by becoming Mexicanized and adopting national symbology, such as the Virgin of Guadalupe or other symbols; or, in the latest films, they respond to the inclusion of difference as a state policy. The elements that are deployed to transmit their meanings are similar to those of the armor of mythological narratives: before it was like this and now it is not, or the opposition good-bad, pure-impure, clean-dirty, a deployment of binary pairs that are equally used in the new languages of the networks.

Faced with the overflowing of communicative margins, we find ourselves in the emergence of global prejudices with a diverse type of technological language. Although the works cited above are focused on Mexico, social networks pulverize cultural meaning to accommodate it in a globality that knows no borders, but fed by opinions and likes that strengthen the "I-actant". One of its expressions can be found in the smashupsa form of myth that rides on the perception of the I-actant who is, in a certain way, a hero (protagonist) who villainizes the other, in this case the Chinese, as we shall see.

Now, similar to the meaning of the post-war graphics that condemned the Chinese presence, in the social networks, as a new language of massive transmission, remains this semantic substance that, despite time, does not change its background by basing its expression on prejudices transmitted by various plastic surfaces ranging from the verbal to the digital.

The phenomenon smashups

The word smashups derives from the musical term mashupThe creation of a new song from the mixture of other compositions. That is to say, something new made by means of pedacería, a kind of bricoleur. Reaching this point was possible thanks to the development of Web 2.0 that managed to combine different contents regardless of their origin, creating results with a short duration. One of its characteristics, and what makes this type of digital expressions relevant, is the experience of the user as the center of everything, since they have the opportunity to be musicians, videomakers, actors, etc.: one becomes the self-referent of the whole. Perhaps its immediate antecedent are its close cousins, the gif (Graphics Interchange Format), a series of frames that are repeated in a loop with no more than 10s of duration and no more than 256 light colors, to transmit an almost immediate idea on the network. In one way or another, they became what will eventually become popularly known as TikTok, the digital platform that takes these messages to a massive and immediate level, offering, as one of its slogans says, "absolute experiences". Thus, unlike the meme or the joke, what matters in the smashups is the moving content nurtured by meanings given through the set of likes and comments that are left. But the meme, unlike the smashup and the gifis temporary and its impact is a social and collaborative product, constituted from the instability of its existence (it is constantly modified), or its duration in time. A meme can gain strength and remain a day or years, no one is in a position to be able to specify its geographical scope and its temporal duration (Lisbona and Rodriguez, 2018: 3).

Now, as we shall see, in terms of this new scripture, the gif has become, in a certain way, a way of responding to certain smashups. Thus, when a content goes viral, it creates a spiral of responses that, whether positive or negative, means a triumph for the author that can be counted in thousands or millions of comments and likeswhich translates into an economic resource. One might ask: what are the consequences of a smashup with racial characteristics go viral? Very much so. It can even cost lives, especially since the development of TikTok, which enhanced the meaning of the messages to be conveyed. The Asian company Bytedance achieved this by allowing users to easily create, edit and upload videoselfies musicals of no more than one minute. They also resorted to the implementation of stunning effects through filters, backgrounds, artificial intelligence, augmented reality and, above all, their ability to invade platforms outside their algorithms, such as Instagram, Facebook, Tumber, Twitter, etc. In addition, they enabled the possibility of sending messages, voting, friend lists and a system of followers and followees.

Let's take a strong example to prove this, even if it's not about racism; it's a TikTok that went viral and cost the protagonists dearly: the boy on the couch. https://www.youtube.com/shorts/P9saOjuUwRQ. Apparently not much happens in this TikTok, which was uploaded by the girlfriend of the boy who comes to visit him. However, the consequences for each of the actors turned out to be extreme, since at first the comments were from friends who congratulated the couple for having a long-distance relationship. The surprise that the girlfriend gave the boy began to motivate adverse and rude reactions, accusing the boy of a notable infidelity. These accusations made the TikTok go viral, and there began a ordeal of the cross for the injured protagonists. Memes and parodies began to be made. The American Eagle brand announced a Halloween costume with the image of the boy on the couch. Several magazines, newspapers, bloggers, such as Rolling Stone, E Online, The Daily Showcreated the hashtag #CouchGuy, which received millions of hits! That's when it became a threat to the participants, as Internet users obsessively investigated them. Several users carried out a kind of intense research and the boyfriends, above all, but also the others appearing in the TikTok, were the subject of school assignments related to their body language and psychological diagnoses, even compared to convicted murderers and made academic theses. Most disturbing came when unknown characters asked them for interviews. One of the boy's neighbors made a video in which the protagonist appeared crossing through the window of his house, which accumulated millions of reproductions. This catapulted content creators who began to relate the boy to all kinds of actions: he had become an object of desire of the most voracious advertisers and late-night fans. There were videos and memes made by users promising that if they reached one million views and likes would confront the boy; yet another suggested that they watch, follow and spy on him to see who was coming in and out of his house. This comment received about 17,800 likes.

We are thus faced with what technology writer Robert McCoy (2021) calls the latest manifestation of a large-scale research culture. But I would ask...what is being investigated, what were the thousands of followers who intervened in the harassment of these kids interested in? The spectacle is sought and the views, comments, etcetera are capitalized on. Social networks have become a market that is willing to do anything to get followers. They seek to become a influencer and manipulate the masses for economic, political and social purposes. A paradigmatic case of its scope is the triumph of the former president, and again president, Donald Trump. It is known that part of his success was due to the illegal manipulation of Facebook's information portfolios. Another case is the triumph of the governor of Nuevo Leon, Mexico, Samuel Garcia, who, in part, managed to win the governorship thanks to his wife, Mariana Rodriguez, influencer who designed his campaign in networks. And reaching the popularity that these actors have depends, undoubtedly, on the myth that they are also reproducing, which we will not address for the moment.

When and why does a TikTok go viral?

There are other smashups that cause an effect contrary to what their primary message promotes. And the superficiality of their content and meaning makes them dangerously viral. The following smashup was designed for and directed towards primary and secondary school students in usa uu. The idea was to convey the right to racial equality, emphasizing that ethnic inclusion is important. However, the opposite happened. https://www.tiktok.com/@tretare__/video/7033512276523109638?is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7033512276523109638

As we can see, the video shows an American child surrounded by Chinese, Africans and Mexicans. Each group is personified by the stereotype with which they have been classified for years. The video accumulated millions of views and several comments questioning its content, which led others to watch it, spread it and thus accumulated millions more views and likes. However, it is worth noting the difference in the comments made in Spanish to those made in English, as many of the latter consider that the video is not racist. Beyond the failure of the clip to convey an anti-racial idea, the fame acquired by its creators was resounding. And as a good myth that it is, variants were created that popularized it. What we are interested in evidencing are the comments it received, in which some show their indignation, but others do not know the reasons for classifying it as racist.

In the following smashupThe profile, in a different profile from the previous one, shows that comments vary and that the controversy over racism is appreciated differently: https://www.tiktok.com/@lecraig/video/693 94839088 53517574?is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=693948390 8853517574)

Now, let's take a look at these two examples of how the messages: https://www.tiktok.com/@josemiguelross/video/6833539942593924357?is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6833539942593924357, https://www.tiktok.com/@oscaramau3/video/7193109378197671173?q=nacho%20taco%20chimichanga&t=1705000280670)

Its behavior is similar to that of myths, the first creative impulse unfolds into thematic possibilities that do not let the message produced by the content die, as in the first smashup and that, as in these last examples, they can break with the plastic of the first, but not with the content, opposing it by means of a sarcastic message that aspires to demonstrate the opposite, although in reality what it affirms is the background of the primary message, but transformed; that is to say, the opposite of what they intend happens, since by reproducing it, it continues to give life to the creative impulse.

Racism and image. Platforms change but stereotypes do not.

Part of the content of these smashups They allude to and are nourished by primary emotions that constitute the content of the message, such as tenderness, love, hate, anger, disgust, fear, which establish and transmit well-defined stereotypes that are often a specific cultural capital: all Indians are stupid, all Chinese are dirty, all blacks smell bad. Racism starts from this principle to send a quick and forceful message about the established prejudice, which is often inherited from generation to generation, to become a "truth". It is undoubtedly one of those mythological structures of long duration (Braudel, 1979) that allude to certain values that are part of a type of collective being. Stereotypes sometimes respond to ethnocentric constructions that, by reducing qualities to basic oppositions, the message becomes fundamental and inflexible: good-bad, beautiful-ugly, clean-dirty, black-white, as they are also transmitted by myths. Both these smashups as the mythological construction respond to a type of cultural judgment in which its vehicle does not matter but its message. It can be a petrogravure on a rock or a meme with a particular message that travels through social networks.

However, when we speak of xenophobic messages, we are referring to the conception of prejudices that have to do with racial, cultural, gender or status differences, that is to say, particular transmissible categories. Thus, classifications become a true hierarchical thinking between cultures, in which some are better than others and this "is so because it is natural". In racist thinking there are no nuances, they are absolute light and dark with no room for the adjective to be relativized: by virtue of my truth I make you the different one, the dirty, the bad, the dangerous, the badly educated, the rapist, etcetera. They are a danger to the "natural families", those who transmit and preserve a civilized, civilizing and ancient tradition; in comparison with the inferiority of those who arrive from distant lands. A simple thought of prejudice that sustains the tradition of a judgment: we are the chosen race and the other does not enter into it.

And this was constitutive in many of the nation-state building policies of the 20th century. xixThey were interested in a eugenic social conformation of the pure races, a prejudice that lasts to this day. They saw in the American Indians, the blacks or the Chinese, a dangerous decadence for their civilizing project, due to the combination of racial genes different from the Caucasians. In political terms, at least in Mexico and certainly in other countries, they spoke of "constructive mestizaje" (Lisbona and Rodríguez, 2018: 3) or positive mestizaje, a policy with which they sought, through miscegenation, to integrate ethnic differences to the European model, by making an analogy of racial and economic processes. If Mexico was economically sunk and did not stand out like European countries, it was because of its historical racial burden. The Indian had to be integrated into the national economy by eliminating his culture and defective biology. Institutions were even created in order to manage the transition to the good race, to the good mestizaje, and State projects began to be introduced in indigenous groups. There were angry debates that considered that "the indigenous race was like that because of its precarious diet": if the indigenous was dark, short and unintelligent, it was due to food, not only quantity but also quality (Lisbona and Rodríguez, 2018). This evolutionist view attempted to substitute corn and tortillas for wheat and bread. Which resulted in, among other culinary delicacies, a cake called guajolota: baguette-like bread filled with a tamale or chilaquiles, and which can be sopped with atole.

These policies turned against Chinese migrants, who, beginning in the mid-1800s, began to arrive in Mexico and America in general, which, over time, led to conflict. In Mexico, racism derived in a sinophobic discourse instrumentalized by the State. The Chinese represented everything negative that the nation was fighting for. They ate badly, they were racially inferior, their eyes and hair made them look like Indians, their languages were almost the same, they were not understood, their dress gave them a backward image. In a word, they were not modern and were considered a degenerate race and accused of the worst barbarities: eating dogs, cats, rats, bugs, rice, raping, killing, smoking opium and trading it, taking advantage of the goodness of the nation by exploiting women (many were sent to the Marias Islands). They began to classify their customs as "degenerate", a danger to the national project and tried at all costs to prevent ethnic mixing. Jorge Gómez Izquierdo (1991: 65) postulates three bases of argument of the State against the Chinese: they took advantage of the poorest women to engender their race with negative racial-genetic limitations and the becoming of good mestizaje; a lacking sense of physical and social hygiene, and an unfair labor competition. It would then be necessary to put limits on them. Lisbona and Rodriguez tell us that "the anti-Chinese movement is intertwined with proposals for national regeneration, and therefore, with the construction of the Chinese as a form of moral panic. Thus, anti-Chineseism contributed to the creation of a language of consensus within the contentious and conflicting project of national construction and state formation" (Lisbona and Rodríguez, 2018: 5-6 and Reñique, 2003: 283). By all means, the state tried to prevent the Chinese from having access to Mexican women, they created anti-Chinese laws and persecuted the Mexican women who married them, from whom they took away, by way of punishment, their privileges as Mexican citizens. Many were deprived of their nationality and patrimony because they were considered Chinese, and then called "chineras". Many were deported to China, without money or relatives, without speaking the language and with no one but their offspring to accompany them. By then, posters and billboards appeared in various media sending anti-Chinese warning messages.

Moreover, this type of politics, as we mentioned, spread in the national consciousness and was projected in both theater and cinema, and there were even songs that, perhaps not consciously, reproduced these stereotypes, such as Cri Cri's two: Chong Ku Fu https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWffebz-FYc y Chinescas: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=irZ48HfhxCo

For the moment, we will not make any more references to the stereotypes of the Chinese in music, since our objective does not go that way. At this point we are interested in showing how the eugenic policies of the State were popularized in an ideological way by incorporating them into other expressions such as cinema, which played a fundamental role in the anti-Chinese imaginary. We mentioned above how Rocío Gonzales de Arce masterfully analyzes these expressions. For example, the film The Amozoc rosary (José Bohr, 1938), a comedy of entanglements produced by Vicente Saisó Piquer, in which the Mexican Daniel "Chino" Herrera plays a Chinese man who disputes the love of the Mexican Chucha with the Mexican Odilón. Throughout the film, the Chinese man is insulted with phrases such as "wretched Asian", "son of the celestial empire", "mentecato Chinese", "And that's what you call eyes? They look like two holes in a piggy bank". And when at the end of the film Odilón thinks that Chucha has decided for the Chinaman, he says to whoever asks him about her: "Don't talk to me about that old espadrille. She preferred saffron blood to red blood". The phrase, a clear reference to the "yellow race" of the Chinese character, expresses, albeit softened through humor, the prejudices and social anxieties of the time surrounding the Chinese and their possible marriage to Mexican women.

Others such as I am a charro in a frock coat (Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1949), Tin Tan and his brother-in-law Marcelo stage a musical number in which they imitate the Chinese owner of a café to avoid paying the bill; or the movie Chinese coffee (Joselito Rodríguez, 1949), in which a man of Chinese origin plays for the first time. Without going any deeper, we would like to point out that each of them uses, to different degrees, certain stereotypes by which the Chinese are known. And even their image operates to censor certain behaviors, such as the film by Ladies Club (Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1956), which openly defends "the natural family" and rejects incipient feminism. Arce tells us that, in one scene, a feminist woman appears, married to a Chinese man. The film concludes when the women are violently subdued by their husbands and "harmony" returns to the disintegrated homes due to feminist ideas. Likewise, this harmony is projected when the marriage between the Mexican woman and the Chinese man is dissolved.

Arce (Gutiérrez and Alvarado, 2025) finds that, through the prejudices already pointed out, the plot epicenter in Mexican cinema is to exclude the Chinese; or to include them, but under the condition of abandoning Chineseness and adopting the national identity. Perhaps the film that most crystallizes this is Yellow Mafia, in which an attempt is made to make these differences evident through a group of gangsters dressed in Asian costumes and with Mexican actors representing Chinese, who speak in a stereotypical Chinese manner, and who recall some passages from Cri Cri's songs: they eat by absorbing food, they enslave, kill, steal, etcetera. The author even suggests that the appearance of the Japanese actor Noé Murayama, playing a Chinese member of the band, explains the lack of recognition of ethnic and cultural differences between different Asian communities. Thus, the cinematographic image becomes part of this great racial mythology. Now, on the part of the State, these messages have operated to reproduce the rejection of racial differences, and not only in the case of the Chinese, but also of Afro-descendants and indigenous people.

We see that cinema, as a semantic and expressive surface, reproduces the xenophobic myth with a forceful pedagogical effect, not because it was propositional but because the message was already there, the only thing it does is to make it evident. This can also be seen through other of the most categorical expressions, television and all the ideology that sustains Televisa as a forger and reproducer of criteria. One more topic to explore.

Stereotypes and memes in times of covid-19

The myth that condemns the Chinese with all those categories that made possible their exclusion from the Mexican nation, and which also happened in countries such as U.S. The problem did not disappear with the passage of time or with inclusive and anti-racist policies in Latin America, on the contrary, it increased. And it certainly became more acute with the covid-19 pandemic. Part of what made this resurface were the declarations of one of the darkest characters in American and international politics, the ultra-right-winger and current president of the United States, Donald Trump, when he declared that covid-19 was the "Chinese pandemic". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0lHpXMsV-ic

The video is interesting because, precisely, we observe a reporter of Chinese origin questioning Trump's racism. And he, with a hint of superiority and noxious authority, ignores the journalist. And one wonders, does he do it because she is of Chinese origin or because he wants to send a strong message about his "truth"? Either way, it had the effect of blaming the Chinese for the pandemic. And one only has to read the comments to realize the approval Trump got from the American public.

One of the consequences that covid-19 showed us was that the racial myth had not disappeared, but was latent in values that gain strength in the face of the uncertainty of the disease. Globally, several countries followed Trump's lead. As long as the blame fell on the Chinese, perhaps the questioning of their health policies would not reach them. This was the case in the United Kingdom, Italy, Russia, Australia and India, where this wave gained so much strength that, on May 8, 2020, the Secretary General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres (2020), declared that: "the pandemic continues to unleash hatred and xenophobia, scapegoating and fear mongering [...] I urge governments now to act to strengthen our society's immunity against the virus of hatred". https://www.hrw.org/es/news/2020/05/12/el-covid-19-aumenta-la-xenofobia-y-el-racismo-contra-los-asiaticos-en-todo-el-mundo.

The declaration had to do with the increase in attacks against this community, which reminds us of those historic cartels in other parts of the world, such as those in Peru.

This rejection became more pronounced in particular with respect to the policies in U.S. The lawmakers argued that they were an "inferior race" that came to degenerate the "purity of their race", as we have said, an argument that was exported in 1911 to the Mexican revolutionary Maderistas in 1911. The legislators argued that they were an "inferior race" that came to degenerate the "purity of their race", as we said, an argument that was exported in 1911 to the Mexican revolutionary Maderistas, who murdered more than 300 Chinese, accusing them of everything already mentioned, in addition to looting their establishments.

In the pandemic, all Asians began to be identified as Chinese, regardless of their nationalities. They undoubtedly operated as scapegoats by criminalizing them for the evil that the world was suffering, as elements of atonement for the inevitable, as René Girard (1983) puts it: frustration produced by an unfulfilled desire and that can be triggered by a community crisis that has to do with famine, natural catastrophes or epidemics. In the medieval bubonic plague, it was the fault of the Jews who poisoned the aquifers, and for this reason they were persecuted (René Girard, 1983). A modern example is also the 2003 pandemic, when the severe acute respiratory syndrome (sars) gave rise to a wave of Sinophobia and Asians, under the classification of Chinese, were blamed; this same population, in 2009 with the pandemic of h1n1suffered harassment of various kinds. Everything got worse for them with covid-19, because Asian people who wanted to be treated in hospitals were often denied care. Even in U.S. a sick man of Peruvian origin, who was considered to be Chinese, was denied medical care (Guterres, 2020).

In the smashups we can find this discourse, beyond its meaning, in the amount of comments that accumulate alluding to Chinese customs and the danger they pose to health. This could be seen during the pandemic, as shown in these YouTube videos chosen at random, but which can be counted by thousands in the networks: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAr9hcvZQX0. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ioFLN8iR4fo

Now, it is interesting to analyze something else in relation to Sinophobia. At the time, the following Twitter feed went viral not because of what it shows, but because of the prejudice it confirms https://twitter.com/RenaSuspendido/status/1578457883934879745?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1578457883934879745%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=about%3Asrcdoc

Regardless of the actant's intention, this smashup received a large number of likes. It is surprising what he awakened in the spectators who, thanks to an accidental action, the comments reeled the actor in a series of disqualifications. "That's what he gets for eating live things", "Surely they won't learn. If they haven't done it in all their history".

Another example is the following: https://www.tiktok.com/@el.antichef/video/6924798530250886406?_r=1&_t=8XRlSuwc4vu&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6924798530250886406

East smashup accumulated 6,281 likes and 238 comments, among them it is worth highlighting some: "I am surprised that they do not eat people too", "do not doubt that because of them there will be more pandemics" and, like these, many more. The language of this video is striking, as it plays with values such as the right of animals, the "poor turtle", the exaggerated disgust of a food tradition and the denigration of the values of others. The comments trigger us to other comments that were posted in response to this TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@ceedee69/video/7098817499285720366?q=china%20come%20ratones&t=1709842504774

And this one led us to one more, from a Puerto Rican who totally disqualifies stocks as dog-eating: https://www.tiktok.com/@maikol7_1/video/6936628946247142661?_r=1&_t=8XRmPPPIjLS&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6936628946247142661

If we analyze these two smashupsWe perceive that they play with two basic conditions of racism: disgust towards the other and disgust towards the way they eat. Their disqualification comes from making visible, even in a ridiculous way, how they eat and what they eat. In the second video, the indignation of the actor, who stars in a series of attention-grabbing adjectives, is noticeable. No matter what they eat, he assures that he is a dog. But the problem is not that it is a skull that is being consumed, but that they are Asians, whose nationality we do not even know, classified as Chinese.

This brings us to a recording in an Uber that gave rise to this article. The driver commented that he no longer goes to Chinese restaurants because with inflation they are eating dogs, that he had seen it in a TikTok, that it was true, that all Chinese eat dogs. And that their restaurants are dirty and full of rats. This driver's reflection connects us with another video that leads us to our argument: the reproduction of the myth of the other as dirty or dangerous. What the driver commented is not something new, it is heard over and over again throughout our sinophobic search.

This is a clear example of how the language and the writing of the smashups and synophobia. One of the most popular TikTok tools is to bend the screen frame and put your face or another scene. As we see in this next TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@vicki11174/video/7067742294354578735?_r=1&_t=8XWl3FHsdmA&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7067742294354578735

The woman, through one of the most forceful tools of language, the gesture, sends a clear message disapproving of what she is looking at. She is blonde, with an accusing face and an indolent expression, what doesn't she like? The way she eats and how the actor eats. Is he Chinese? It is not known, because in TikTok you can dub voices and take some facts out of context for a certain purpose. In this case it is simply the disapproval of difference, by letting us see how the actantial function operates within a given context. Now, as it was said, the message loop is unfolding and receives responses, which are shown in the following TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@elpanakevs/video/6929278594996866310?_r=1&_t=8XWoS2KwPUj&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6929278594996866310

This can be classified from a racialized, disqualifying look and under an aprioristic paradigm of what is good to eat. A whole classification can be created from the food videos that we will see later, it is possible to spend weeks watching this type of video. smashups. From these first ones, of reprobatory origin, others are derived that have to do with the imitation of the stereotype, such as the following case: https://www.tiktok.com/@lorenamorbel/video/7113711071726177541?_r=1&_t=8XWpGPd12kI&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7113711071726177541

However, food is an element that becomes one of the privileged contents of synophobic tiktokeros, since it alludes to one of the senses that has the greatest cultural impact and that, undoubtedly, like myths, dialogue with each other, which often makes them viral. We once again understand how networks invade the field of myth to become part of the classification through sensations and the values of cultures. Among other characteristics that make the myth and the mythical common smashups is their ability to operate through snippets, bits and pieces of historical or recent events. Any element that they manage to take out of context, include it within a particular value and launch a categorical message is useful. Such are the mythological devices, implicit or explicit, which are transformed from one community to another, from one region to another, or even from one continent to another. The case of Mesoamerican myths is a decisive example; if we follow the trail, let us say, of the myth of the birth of the Sun Father, we find that it transcends spatial and temporal borders, appearing in several pre-Hispanic and current groups, not only of the Mesoamerican tradition but even with Pueblo groups, such as the Hopis or Zunis. If in this case it is the Sun Father who is born through the throwing of a crippled child into the fire, to demonstrate that courage and renunciation are substantial examples of "good being and doing", in the case of the smashups the myth of sinophobia is emerging with historical prejudices, even if its transmission channel is not necessarily, or exclusively, the oral one. We see that it is updated through the networks and that it takes on a massive meaning that responds to the laws of transformation.

Thus, this type of content could be called mythological instrumentalism of disgustThis is because the actor who creates this type of reproachful content appeals to primary stereotypes, what is good and not good to eat, to send an absolute and racialized message, in which his disqualification appeals to the disgust of what is eaten and how it is eaten, and which carries implicit physical and moral discrimination. And this mythical primary stereotype can lead you to others, even dangerous ones: https://www.tiktok.com/@dutchmemes420/video/6977694269012331782?_r=1&_t=8XWxPuUBuK6&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6977694269012331782

It is noteworthy that the previous smashup was blocked from TikTok and no longer allows access to it. Comments supporting the person making the video could be heard, but with racialized comments: "even if she is Chinese she should be respected" or "why treat her like that, if she is also pretty". What is most striking is the amount of likes and comments, some of which stand out for being frankly threatening: "if I were the one who hit you I would kill you", or "Chinese whore" or "I would stick it in you, even if it rotted". And two responses are striking because they direct us to other pages with frankly threatening content: https://www.tiktok.com/@chucho236/video/7018711456711478533?_r=1&_t=8XWxvdS9HxV&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7018711456711478533

Looking at that response, it makes one curious about the page that publishes this, where one finds veiled threatening, racist and even fascist language. The smashup in itself is not superficially dangerous, until it is contextualized in the whole content of the page, strange, obscure, with a coded language. Let's look at some examples: https://www.tiktok.com/@odio_bolivia_666/video/706243754550 5869061?_r=1&_t=8XWyK7zZJzR&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7062437545505869061

Up to this point, we have alluded to a few examples of the sinophobic myth. As a methodological tool, we have just drawn a crossroads of disciplines that lead us to a result: the deciphering of the myth in the networks.

Conclution

In the article "Hateful and offensive discourse in the Twitter social network towards the Chinese collective. Analysis of Sinophobia: from covert to explicit cultural rejection" (2024), Valle de Frutos, using a statistical methodology based on the algorithm machine learning concludes that, through this platform, peaks of hatred or offensiveness towards the Chinese can be traced in Spain, depending very much on several conditions. He is interested in distinguishing between hatred and offense towards this collective. The former can be influenced by a media or political agenda, and refers to a covert rejection, related to prejudices towards this difference. The second implies an explicit rejection that involves visible hostility and is associated with negative cultural aspects. While the work seems to us pioneering and relevant, in our view the distinction creates a false difference in something that can be called sinophobia. Our distance with this work is that for us a foundational mythological state prevails, which you arrive at not based on a statistical methodology but on a comparative and interdisciplinary one, but which, as a basis, has visual anthropology and digital ethnography. This does not mean that we downplay the importance of this work, on the contrary, it seems to us complementary. What we wanted to demonstrate is that the analysis can go into mythological loops and decipher their relationship between signifier (timeless) and signified (temporal). This was done thanks to the iconographic analysis of not only the smashupsbut from its comparison with other visual and auditory figures and the understanding of the actantial functions. The foundational myth has operated and operates not only in national politics, but also moves, thanks to social networks, to a global and international scenario. And if not, let's see how the ultra-right in countries like U.S.The Netherlands, Argentina, Italy base their discourse on that old myth, which also accompanies Sinophobia, of the manifest destinyThe "countries chosen by God" that have the task of expanding their territory.

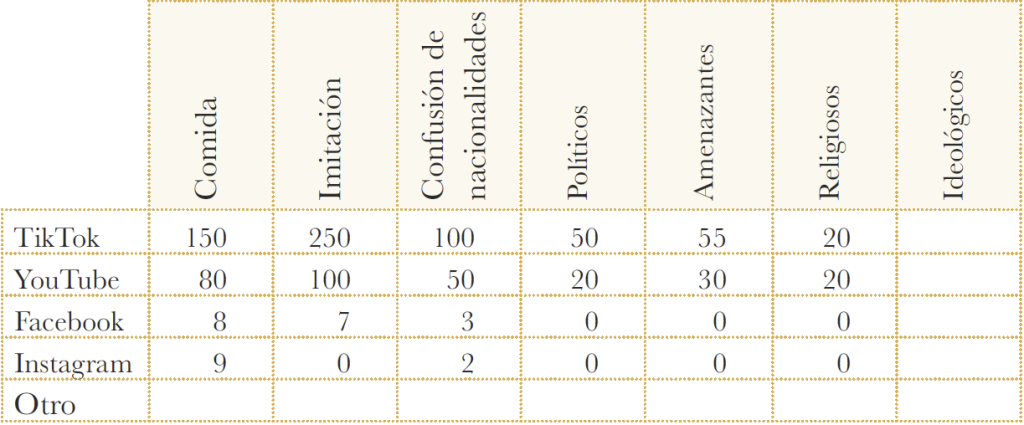

Now, while doing digital fieldwork, we found different samples that supported our hypothesis about the mythological bias. Therefore, we made a table that lets you see our search and, if this is a start, among the smashups and stereotypes, we observed several continuities that can be classified as follows:

For the moment, and in this space, it is impossible to analyze every element we find. But in the sampling, a fulminating conclusion emerges: the network is a free medium to manifest racial prejudices. And sinophobia flows in them as phenomena such as pandemics, wars or political campaigns emerge. Thus, the networks slip opinions on a given phenomenon, in this case Sinophobia, which can encompass the world as a whole, using the myth as an ethical and moral device that aims its darts at Asians, all of them considered as Chinese. Undoubtedly they suffer a persecution in networks that many times is passed on to the streets, as in the case of the couch boy, that may very well surpass its digital borders and become a danger to some citizens. This can be seen in videos in which U.S. citizens beat up an Asian; even in Chihuahua, several Mexicans murdered a Chinese man for fear of contagion (Círculo Newspaper am, 2020, https://www.am.com.mx/news/2020/4/22/mexicanos-asesinan-un-chino-por-miedo-coronavirus-404492.html).

One of the difficulties we encounter is the speed with which we publish our smashups and the speed with which they disappear or, the most successful ones, are transformed into others and others. For this reason, many of these samples have disappeared, or those responsible have discarded the content. From this perspective, what Valle de Frutos (2024: 8) says, that sinophobia is not constant, but suffers peaks depending on social conditions, seems to us to be completely accurate. During the pandemic, many published things related to Chinese people and the discomfort they caused them. When the pandemic passed, they lowered the content.

Much remains to be said about what has been analyzed in this article. At the same time, we must compare the smashups with other expressions, such as theater or soap operas, a search that, as Arce does, can highlight the sinophobic discourse that has characterized certain nations, and particularly Mexico, with its political, artistic and musical production.

To conclude, we would like to point out how a meme operates by expressing a forceful content, that is to say, an image is worth a thousand words, and as an example, image 4 needs no further explanation, it simply states a reality that focuses on the problem of our argumentation.

Bibliography

Braudel, Fernand (1979). La larga duración en la historia y las ciencias sociales. Madrid: Alianza.

Eco, Umberto (1999) [1968]. La estructura ausente. Introducción a la semántica. México: Lumen.

Girard, René (1983). La violencia y lo sagrado. Barcelona: Anagrama.

González de Arce, Rocío (2025). “De Café de chinos a El complot mongol: discursos cinematográficos de segregación, exclusión, integración e inclusión en torno a las comunidades chinas en Latinoamérica”, en Arturo Gutiérrez del Ángel y Greta Alvarado (eds.). Memoria de las familias chinas en México. México: Palabra de Clío.

Gómez Izquierdo, José J. (1991). El movimiento antichino en México (1871-1934). Problemas del racismo y del nacionalismo durante la Revolución mexicana. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Greimas, Algirdas Julien (1985) [1982]. “Elementos para una teoría de la interpretación del relato mítico”, en Análisis estructural del relato. México: Premiá (La red de Jonás, Estudios).

Guterrez, Antonio (2020). “El covid-19 aumenta la xenofobia y el racismo contra los asiáticos en todo el mundo”, en Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/es/news/2020/05/12/el-covid-19-aumenta-la-xenofobia-y-el-racismo-contra-los-asiaticos-en-todo-el-mundo

Gutiérrez del Ángel, Arturo y Greta Alvarado (eds. 2025), Memorias de la comunidad china a la luz de la luna: reflejos entre México y Latinoamérica, México: México, Palabra de Clío.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1995 [1978]). Mito y significado. Madrid: Alianza, pp. 27-28.

— (1987 [1974]), “La estructura de los mitos”, en Antropología estructural. Buenos Aires: Paidós, pp. 153-163.

Lisbona G., Miguel y Enrique Rodríguez Balam (2018). “Estereotipos sobre los chinos en México: de la imagen caricaturesca al meme en internet”, Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital, vol. 13: pp. 2-30.

McCoy, Robert (2021). “El ‘Chico del sofá’ de TikTok y las investigaciones masivas en internet”, Letras Libres. México. Consultado en: https://letraslibres.com/ciencia-y-tecnologia/el-chico-del-sofa-de-tiktok-y-las-investigaciones-masivas-en-internet/

Moore, Edward C. (1972). Charles S. Peirce: The Essential Writings. Nueva York: Harper & Row, Reimpresión de Prometheus Books.

Reñique, Gerardo (2003). “Región, raza y nación en el antichinismo sonorense”, en Aarón Grageda (coord.). Seis expulsiones y un adiós. Despojos y expulsiones en Sonora. México: unison/Plaza y Valdés, pp. 231-289.

Saussure, Ferdinand (1985). Curso de lingüística en general. Barcelona: Planeta.

Valle de Frutos, Sonia (2024). “Discurso de odio y ofensivo en la red social Twitter hacia el colectivo chino. Análisis de la sinofobia: del rechazo cultural encubierto al explícito”, en Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social, “Disertaciones”, 17 (1), pp. 2-19. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/disertaciones/a.13347

Bibliography Smashups

Times, Hard [@hardtimes8] (7 de octubre de 2021). Couch guy #tiktok #viral #couchguy video [YouTube, original TikTok] https://www.youtube.com/shorts/P9saOjuUwRQ

Tretare_ [tretare_] (22 de noviembre de 2021). Video antiracista #humor (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@tretare__/video/7033512276523109638?is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7033 512276523109638

Lecraig, [Lecraig] (14 de marzo de 2021). Most racist anti-racist #memes #meme #foryou #fy#fyp #foryoupage #wegottocelebrateourdifferences #celebrateourdifferences #racist # antiracist, (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@lecraig/video/6939483908853517574?is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=693948 3908853517574

Ross, José Miguel [@josemiguelross] (1 de junio de 2020). Nacho, Taco, Chimichanga que hermoso es el español #fyp#memes #mexico #parati #comedia (video TikTok) https://www.tiktok.com/@josemiguelross/video/6833539942593924357?is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6833539942593924357

Amaury, Oscar [@oscaramau3] (enero 26 de 2023). Lo hicimos de joda, pero se mancharon con nosotros los mexicanos que “nacho chimichanga” oh mi taco #fyp #diferencias #diferenciasentrepaises #diferences. https://www.tiktok.com/@oscaramau3/video/7193109378197671173?q=nacho%20taco%20chimichanga&t=1705000280670

Cri-Cri, el grillito cantor [@CriCriElGrillitoCantor] (2019). Chong Ki Fu. (video YouTube, Music by Cri-Cri performing Chong Ki Fu [Cover Audio]). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWffebz-FYc

Cri-Cri, el grillito cantor [@CriCriElGrillitoCantor] (8 de noviembre de 2014). Chinescas. (video YouTube Chinescas Cri-Cri Por El Mundo). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=irZ48HfhxCo

El Mundo [@elmundo] (12 de mayo de 2020). Donald Trump, al ser preguntado por las cifras de muertos: “Preguntad a China”, #Trump #EEUU #Coronavirus, (video Youtube), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0lHpXMsV-ic

El País [@elpais] (12 de junio de 2017). Una canadiense a unos trabajadores chinos: “¡Volved a China!” (video YouTube), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAr9hcvZQX0

El Universal [@eluniversal] (13 de julio de 2023). Streamer tailandesa denuncia racismo sufrido en Bélgica (video YouTube, El Universal), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ioFLN8iR4fo

El Renacido [@RenaSido] (7 de octubre de 2022). Final inesperado (video Twitter), https://twitter.com/RenaSuspendido/status/1578457883934 879745?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1578457883934879745%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=about%3Asrcdoc

El.Antichef [@el.antichef] (2 de febrero de 2021). No sé cómo hacen para comer todo lo que se mueve, #comida #tortuga #chnos, (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@el.antichef/video/69247 98530250886406?_r=1&_t=8XRlSuwc4vu&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6924798530250886406

Cee, Dee69 [@ceedee69] (17 de mayo de 2017). whit sauced and tomatoes, #blackcreator #blackeducator #teacherlife #ceedee, (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@ceedee69/video/7098817499285720366?q=china%20come%20ratones&t=1709842504774

MePc Office [@maiko17_1] (6 de marzo de 2021). Los chinos comen perro (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@maikol7_1/video/6936628946247142661?_r=1&_t=8XRmPPPIjLS&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6936628946247142661

Vicky san [@vicki11174] (2 de febrero de 2022). Que raro comen los chinos, #dúo @brenna0900, (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@vicki11174/video/7067742294354578735?_r=1&_t=8XWl3FHsdmA&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7067742294354578735

Ortega, Kevin [@elpanakevs] (14 de febrero de 2022). El resto del mundo, #pegar un video de @rich.65 @fyp #parati #food, (video TikTok) https://www.tiktok.com/@elpanakevs/video/6929278594996866310?_r=1&_t=8XWoS2KwPUj&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=6929278594996866310

Morebel, Lorena [@loreamorbel] (26 de junio de 2022). Comiendo como chinos, aún no sé lo que hablo jiji, #comedia #fip (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@lorenamorbel/video/7113711071726177541?_r=1&_t=8XWpGPd12kI&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=71137 11071726177541

Farina [@farinalinibeth] (17 de septiembre de 2022). Yo imitando a los chinos, (video TikTok). https://www.tiktok.com/@farinalamasviral/video/7144394853051288837?_r=1&_t=8XWpLe8kMWU&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7144394853051288837

Garduño, Jesús [@chucho236] (13 de octubre de 2021). Eric y su fobia a los chinos XD, #foryou southpark #fyp #ericcartman, (video TikTok) https://www.tiktok.com/@chucho236/video/701871145671147 8533?_r=1&_t=8XWxvdS9HxV&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7018711456711478533

Xd, Nose [@odio_bolivia_666] (2 de agosto de 2022). Taiwan un país libre, (video TikTok), https://www.tiktok.com/@odio_bolivia_666/video/7062437545505869061?_r=1&_t=8XWyK7zZJzR&is_from_webapp=v1&item_id=7062437545505869061

The doctor Arturo Gutierrez del Angel is a full time researcher in the Anthropological Sciences program at El Colegio de San Luis; he is interested in mythological, oneiric, ritual, and aesthetic processes, as well as in Chinese migration and its social repercussions. He has worked with cultures of western Mexico, such as Huichol and Cora, and people groups of the southwestern United States. She currently has two projects: one on Sinophobia and its social impact; the other on the dream world as a form of knowledge in different cultures.