Companies of Negritos. Representations of "lo negro" in the theatrical scene of Mérida during the first decades of the 20th century.

- Luisangel García Yeladaqui

- ― see biodata

Companies of Negritos. Representations of "lo negro" in the theatrical scene of Mérida during the first decades of the 20th century.

Receipt: September 21, 2024

Acceptance: February 26, 2025

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to identify the social representations of "the black" that were present in the theatrical scene of Mérida, Yucatán, during the first decades of the twentieth century, and to identify the social representations that were present in the theatrical scene of Mérida, Yucatán, during the first decades of the twentieth century. xxThe role of the black man, the black professor or the mulatto woman was incarnated in actors and actresses playing the role of the negrito, the black professor or the mulatto woman. Likewise, these representations transcended the theater to also appear in stories of popular characters, carnivals and advertising. For these purposes, one of the main means of communication of the time was consulted: the newspaper. Through the search, compilation and analysis of these newspaper sources, we found images that circulated in different cultural spaces of the city, so the analysis of visual sources was fundamental.

Keywords: afrodescendants, cultural circulations, stereotypes, social representations, theater in Yucatan

black theater companies: stage representations of "blackness" in mérida during the early twentieth century

This article examines social representations of "blackness" on stage in Mérida, Yucatán, during the early decades of the twentieth century, focusing on actors who played the roles of "el Negrito", "el Negro Catedrático", and "la Mulata". These representations extended beyond the theater to popular fiction characters, Carnival, and advertising. The search, collection, and analysis of newspapers -the foremost media source of images during those years- reveals how these characters circulated in various cultural spaces across the city, making the analysis of visual sources essential to the research.

Keywords: social representations, Afro-descendants, theater in Yucatán, cultural circulation, stereotypes.

Beginning in 1890, the city of Mérida entered a stage of modernization and urban development thanks to the economic boom generated by the henequen industry (Hansen and Bastarrachea, 1984). Thus, from the second half of the xixThe inhabitants of Merida would go through a process that included the construction of railroads, the paving of streets, the installation of telephone poles, the establishment of banks and large businesses, the opening of schools, a greater influx of national and foreign migrants, and greater facilities for travel outside of Mexico (Hansen and Bastarrachea, 1984).

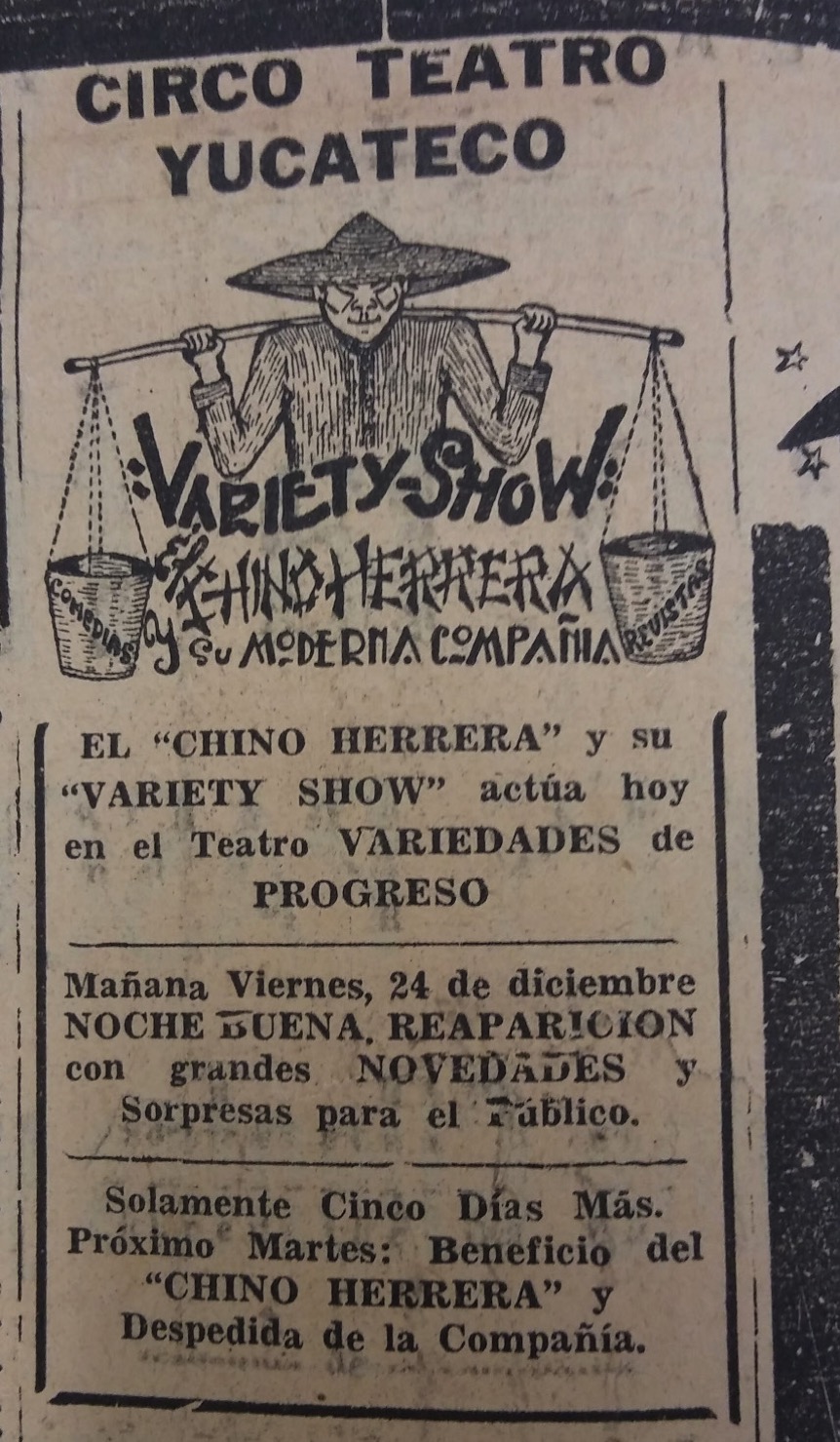

One of the consequences of economic progress was the appearance of new enclosures and spaces designed to meet the recreational and leisure needs of a growing population.1 Thus, the theater would stand out as one of the main entertainment options in the city, gradually expanding its offer throughout the following decades. By the second decade of the century xxIn the past, Mérida already had a total of eight different theaters: the Peón Contreras, the Salón Iris, the Salón Independencia, the Apolo, the Circo Teatro Yucateco, the Salón Principal, the Fénix movie theater and the Salón Hidalgo.2

Whether for theater, for circus performances or for shows In addition to the variety shows, the Yucatecan capital had several establishments where the companies of artists, who were constantly arriving in the city, could perform. Although other forms of entertainment such as cinema became more important after the turn of the century, the influx of theatrical companies would not stop. Theater in Yucatán is a subject that has been researched before. One of the earliest works is the book by Alejandro Cervera Andrade titled El teatro regional de Yucatán (1947), in which he explains how pre-Columbian Maya and Spanish colonial traditions were the first pillars of Yucatecan theatrical production, thus beginning to acquire regional dyes that rescued indigenous and European elements. Cervera Andrade also recovers the names of the main actors, scriptwriters and characters that appeared in the plays.

Another of the most complete texts on theater in Yucatán is that of Fernando Muñoz (1987), which has the same title as Cervera Andrade's book. In addition to including the pre-Hispanic and colonial past of regional theater, Fernando Muñoz compiles interviews with actors and incorporates a list of the names of the principal works of regional theater (with the names of the authors). Finally, two more modern works about theater in Yucatán are the following: El teatro regional yucateco (2005) y Recuerdos de teatro. Entrevistas a personalidades del teatro regional (2010), both written by Gilma Tuyub Castillo. The contribution of this author is that she classifies the characters that used to appear in the Yucatecan regional theater of the first decades of the century. xxincluding the actors' and actresses' names, manner of dress, physical and moral attributes, and so on.

As several researchers have argued (Fumero, 1996; Zayas de Lima, 2005; Villegas, 2005), theater is a reflection of social relations and dynamics. For this reason, in the first half of the first half of the century xxIn this way, the elites and some Yucatecan intellectuals were interested in highlighting that which was typical of Yucatán, distinguishing what was culturally particular in the regional sphere. Thus, Yucatecan regional theater constructed characters such as the mestizo and his female version, the mestiza, who were considered representatives of the Mayan past mixed with Spanish identity, since their morphological and cultural characteristics represented what was unique and authentic for Yucatecans (Figueroa Magaña, 2013).

Thus, the works of Cervera Andrade, Muñoz and Tuyub Castillo ended up giving greater weight to the mestizo, the mestiza and the Mayan Indian, since they made little mention of other characters that we can classify as foreigners: the negrito, the Chinese and the Arab or Turk (see image 1).3 However, the fact that they are included allows us to confirm the existence of other characters; and, therefore, of a certain space of representation for those individuals who did not fit the Yucatecan identity of the time.

Then, along with the regional characters, others appeared that were differentiated from the Yucatecan; thus showing that the theater in Mérida was composed of a wider diversity of otherness than the official discourse let on. Thus, there is evidence of the negrito as a character recurrent to a certain extent in the theatrical production of the city, but that at a certain point seems to have disappeared, to the extent that the current exponents of Yucatecan regional theater know or remember very little of this character.4

Elisabeth Cunin, in her article "Negros y negritos en Yucatán en la primera mitad del siglo xx. Mestizaje, región, raza" (2009), affirms that one space in which we can find representations of Afro-descendants in Mérida is in its regional theater; there it is possible to know the perception of these groups and how their apparent oblivion allows us to understand the secondary and even invisible role they have occupied in the history of Yucatán.

Thus, this paper seeks to understand to what extent the representations of the negrito and the mulata in the theatrical scene of Mérida (and also in other spaces) can shed light on the processes that intervened so that the Afro-descendant population -present in Yucatán since colonial times- would be excluded from Yucatecan identity, and in its place "the black" would become entrenched as a foreign element, more specifically Cuban.

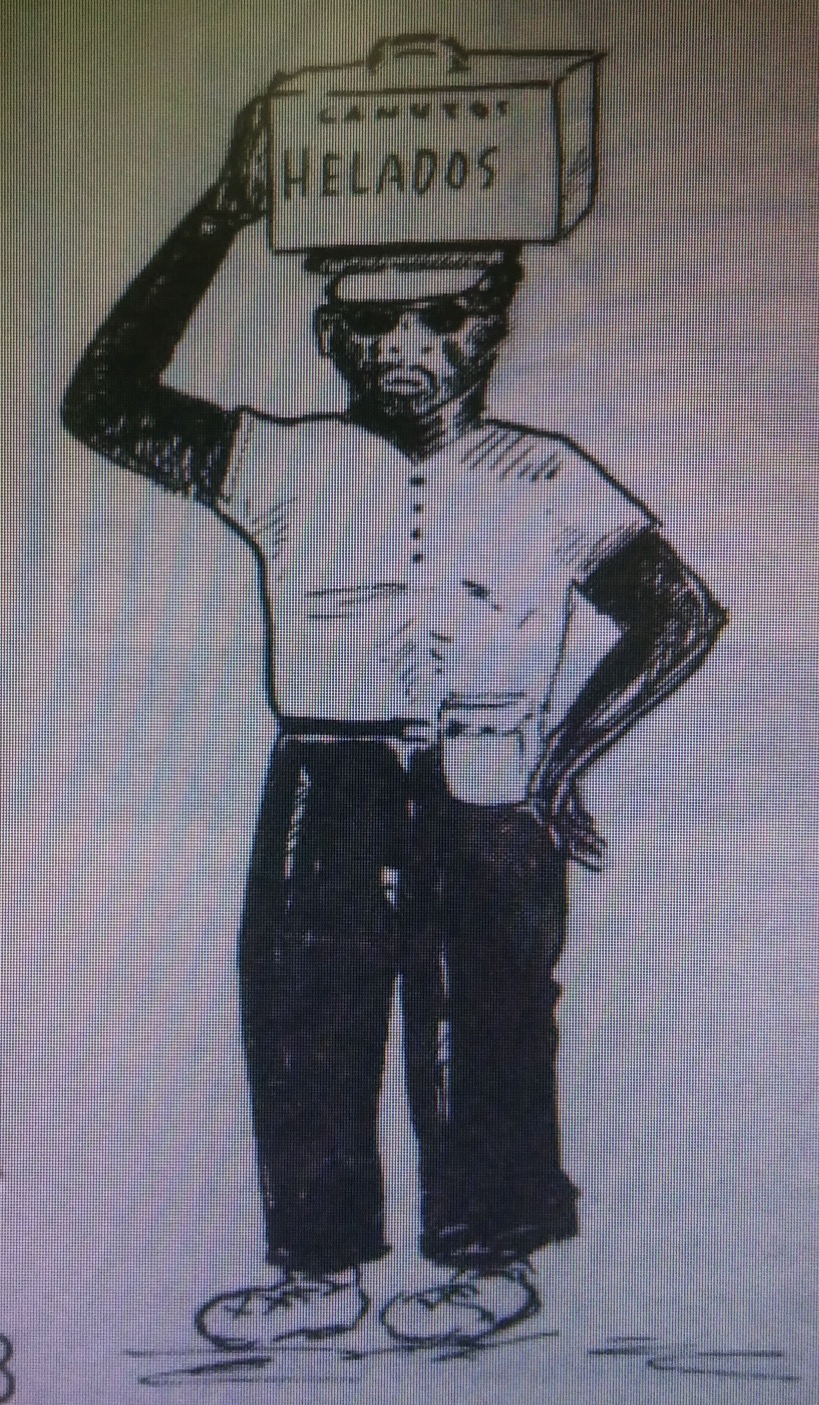

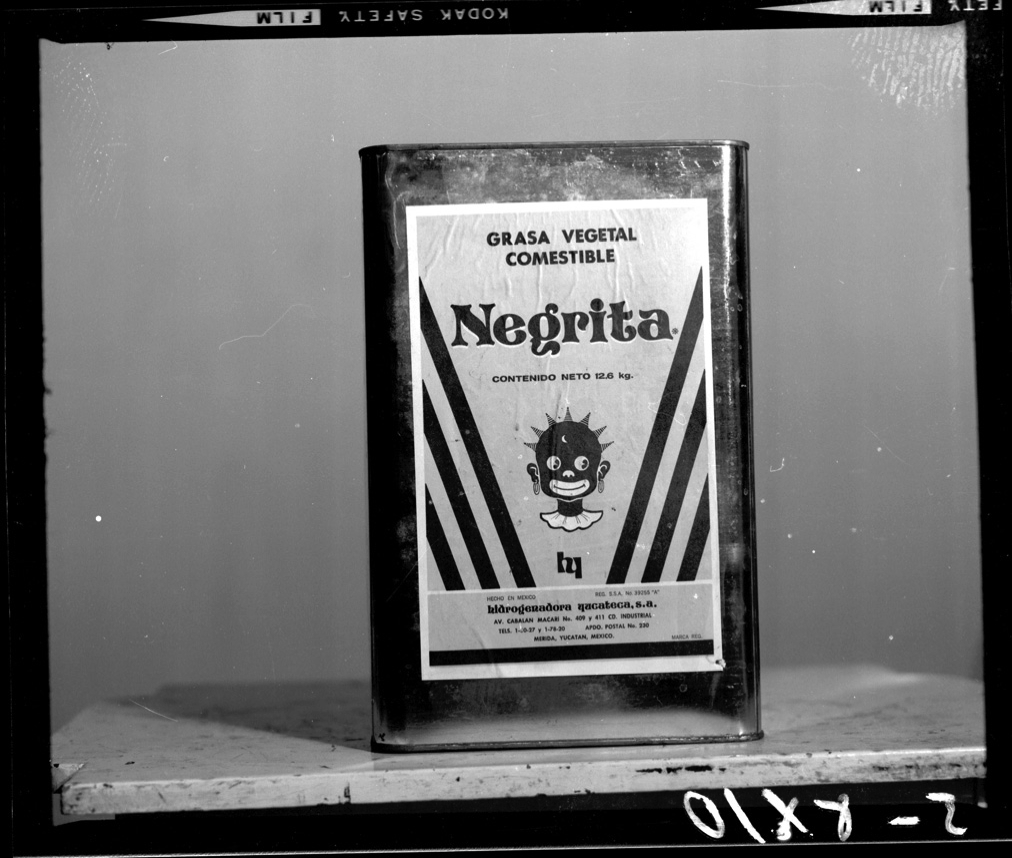

To begin with, the characters of the negrito and his female counterpart, the mulatto, were present on the theatrical stages of that city, but they also existed as characters of everyday life, as advertisements in newspapers and, even, we still find them in the names of products and street plaques (see images 2 and 3). Despite such evidence, their presence seems to have been suppressed from regional and official history for reasons that will be analyzed later.

First of all, it is essential to define what is meant by social representations. To do so, we base ourselves on Serge Moscovici's theory, who states that these can be conceptualized as a form of knowledge that people use to assimilate what is strange to them or comes to them from an unknown environment, always depending on the sociocultural context in which they are located (Farr, 1983).

Likewise, Silvia Valencia Abundiz argues that one of the characteristics of representations should be the "articulation between the subject and the social" (Valencia Abundiz, 2007: 52), since they should focus on the links and relationships between practical knowledge or common sense (opinions, images, attitudes, prejudices, beliefs, values) and the social contexts of interaction between individuals or groups.

Therefore, in their construction, representations are nourished by traditions, beliefs, emotions/feelings, previous knowledge and the respective ideological, political and cultural context that frames them (Valencia Abundiz, 2007). Based on the above elements, it is the individual who interprets social reality, who gives meaning to the world in which he/she lives, orients his/her conduct and behavior and defines identities, although not before having interacted with other subjects.

In their interpretation of reality, individuals or groups of individuals generally face elements foreign to their culture, being the creation of exaggerated or stereotyped images one of the possible results; such images end up naturalizing and reducing what is represented to certain physical, cognitive, moral and behavioral traits to make them static and immovable (Ghidoli, 2016). Such was the case of black characters in Yucatecan theater, who reproduced ideas or representations that circulated in different contexts (European, American, Latin American, among others).

Another term that is important to define in this document is "blackness". Without pretending to exhaust all the debate that exists around this concept, it refers to phenotypic traits, character, personality, virtues and vices, attitudes, aptitudes, behaviors and even tastes and interests associated with Afro-descendant groups (Cunin, 2009; Pérez Montfort, Rinaudo and Ávila Domínguez, 2011; Nederveen Pieterse, 2013). In other words, the representations that emerged and circulated from people of African origin or descent.

Now, in the theatrical scene of Mérida we find that, through a series of artistic expressions, images and ideas, black characters were represented by means of certain physical traits, attitudes and even abilities that people associated and naturalized with black and Afro-descendant groups. To mention some of the aspects represented are the black skin color, humorous attitudes, singing and dancing skills, violence and aggressiveness, lewd and hypersexualized attitudes and, in general, the taste for fun.

All these elements circulated through different historical contexts, and also reached Yucatán, and the theater was one of the spaces that used them. And it is that, especially well into the xxThe strong Cuban-Yucatecan ties would propitiate a fluid circulation of artists who traveled from Cuba to Mérida and vice versa, increasing the presence of these groups and their shows in entertainment spaces, which were loaded with the representation of black characters (Pérez Montfort, 2007).

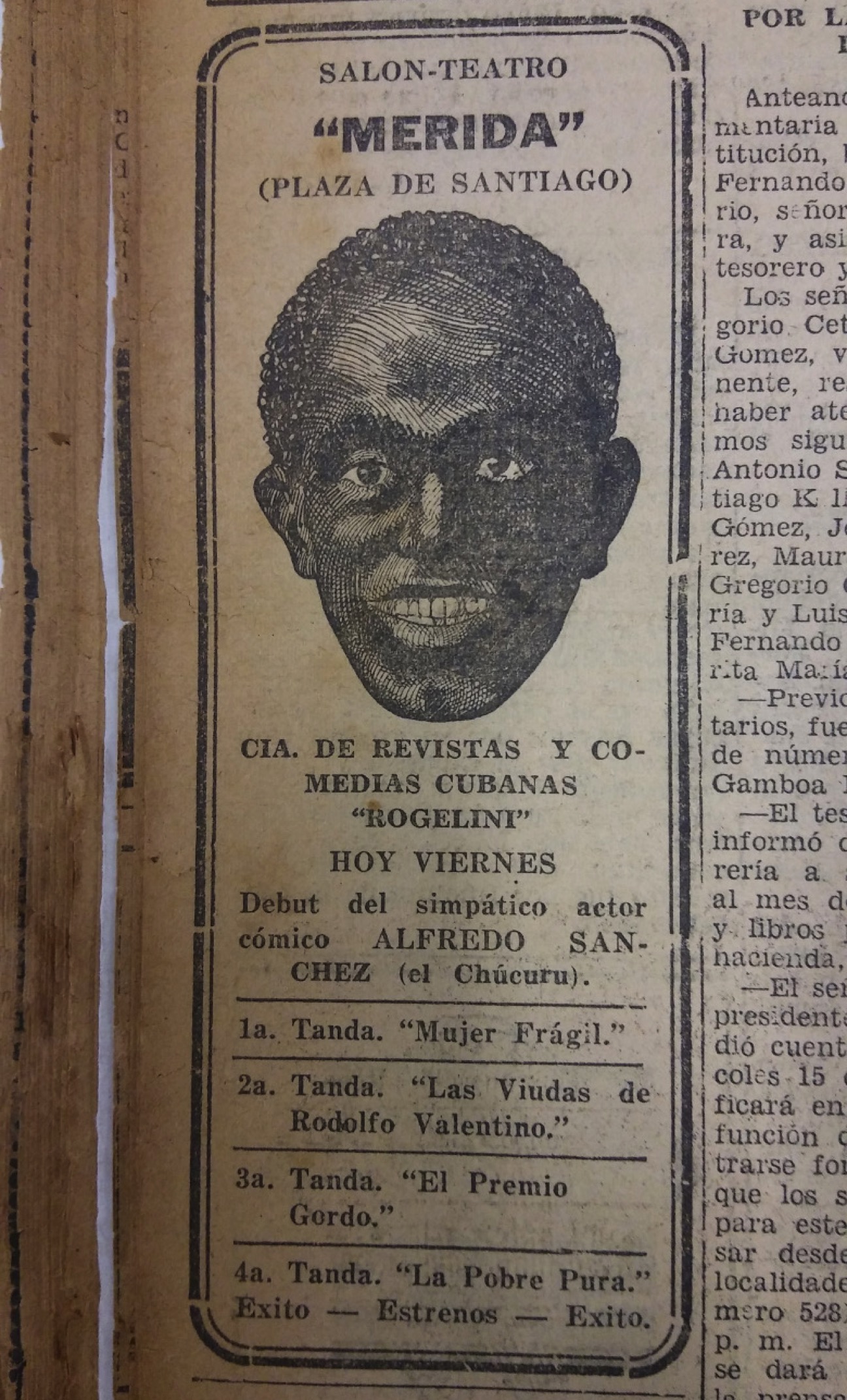

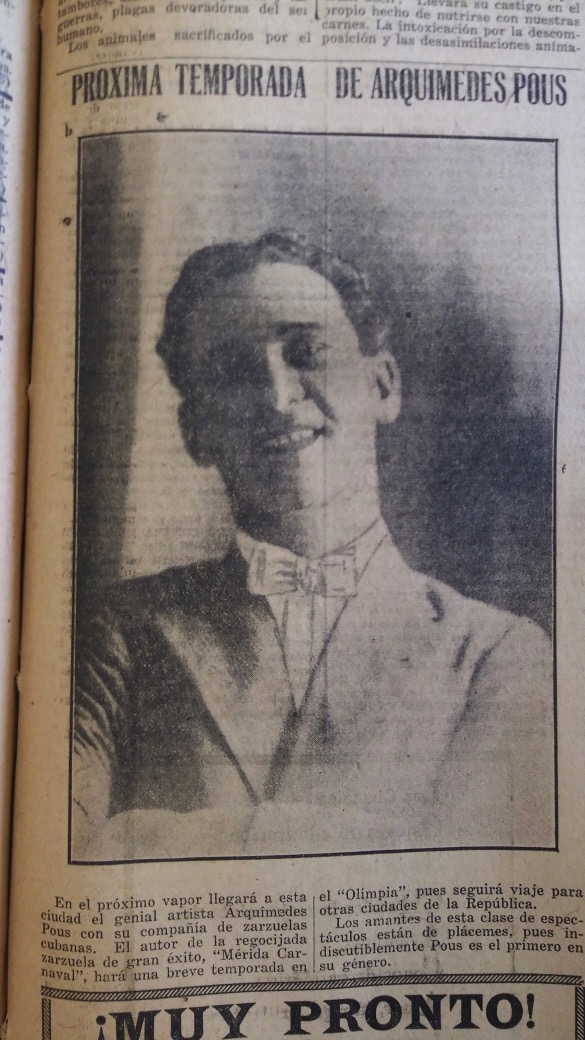

Proof of this is found in the newspapers of the time that allow us to confirm such links and cultural exchanges between Cuba and Yucatán: through the different advertisements, propaganda and entertainment billboards (mainly cinema and theater) that promoted shows and shows for fun and entertainment. Among this type of publications, Cuban theatrical companies that presented genres such as revue, zarzuela and comedy, characterized by their humorous and satirizing scenes of reality, stand out.

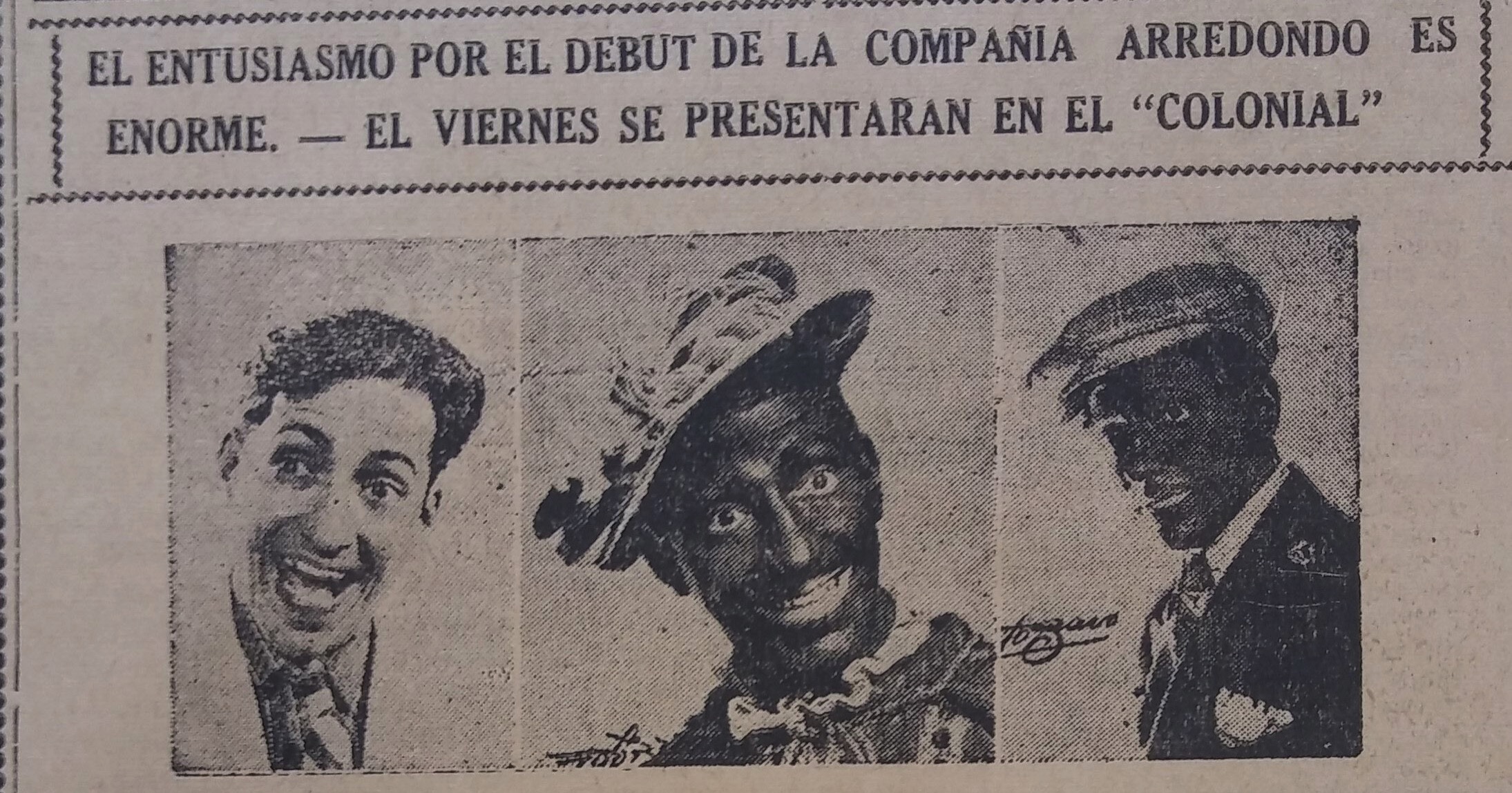

According to the newspapers and the press, this type of show was very popular with the public in Mérida.5 Likewise, one of the most recurrent and even main characters in these stagings was the negrito, a character so essential that it was even usual to see the owner of the theatrical company in this role, characterized in the style of the "negrito". blackface6 and representing it in the works, as we can see in the following images (see image 4):

In both cases they were Cuban theatrical companies in which the owner, Alfonso Rogelini, in the first case, and Enrique Arredondo, in the second, played the role of the negrito. Arredondo, for example, would star in December 1943 in a play described by the Diario de Yucatán The play was called "Cuban-Yucatecan" because it featured two of the great exponents of Yucatecan theater, Héctor "Cholo" Herrera and Ofelia Zapata, in the roles of the mestizo and the mestiza, respectively. The play was called Tunkules and maracasThe tunkul is a Mayan instrument representative of Yucatan and the maracas, from Cuba.

In the words of Enrique Arredondo (1981), the play was about a family of Yucatecans traveling to Cuba and a little black man who showed them the beauties of the island. In return, the family invited the negrito to Yucatán so that he could also see the wonders of the place. The whole play was a strong and clear expression of the links between Cuba and Yucatán, since it tried to show the cordial and friendly relations between Cubans and Yucatecans; however, I consider that the fact of separating the characters and their place of origin accentuates the idea of the Afro-Cuban, the negrito and his representations as elements of foreignness but not of total rejection, since the success achieved would lead to an increase in the admission prices to see the play (Diario de YucatánNovember-December 1943).

Another play that allows us to know the type of representations of the negrito is The talking dogwhich can be found in Alejandra Burgos Carrillo's bachelor's thesis (2014). Written by Yucatecan José "Chato" Duarte in 1922, this play introduces us to the characters Cristina and Matías, two mestizos who are husband and wife; their son Nicolás, who studies in the United States; and Crispín, a young black man of Cuban origin who sells bottles. In the play, Nicolás invents that a teacher at his school has managed to teach dogs to read and write, so he asks his parents to send him Boxni, a dog he left with them.7 Matías, who is enthusiastic about the idea, goes to Crispín to accompany him on his voyage; but, as his wife predicted, the trip goes wrong because they take another boat, lose their suitcases, their money is stolen and Crispín ends up beaten.

Crispín's character is described as a black man dressed in rags who, because of his occupation, carried a sack with empty bottles. Ironically Matías calls him "chel", which is a Mayan word used to designate people with white skin or blond hair. Crispín omits the "s" from some words, as part of his portrayal includes black speech;8 He is also cunning and takes advantage of Matias' naivety, telling him that he lived for five years in New York, that he speaks English and that he studied mathematics, philosophy, history and ethics in the United States, which is why Matias takes him on the trip. His taste for rumba is another characteristic of the character, who sings and dances on two occasions in the hope of infecting others.

The representation of Crispín in this work is that of the black congo or bozal, originally from the Cuban bufo. This type of character is characterized by his attachment to his African roots, by a peculiar way of speaking Spanish and by a supposed state of uncivilization that, in the case of Crispín, is associated to his way of dressing and even to the way he earns his living. At the same time, this character recovers the sly, cheerful and comedian, perceptions that were also held of the Afro-descendant population.

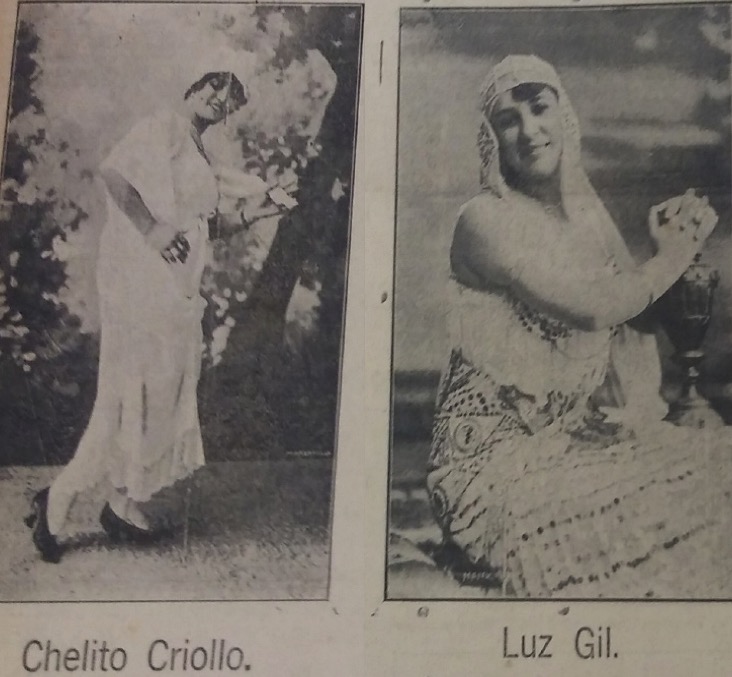

Together with the negrito, the mulata acted as the feminine representation of "the black", as we can see in image number 5. In the plays, this woman was usually in charge of sowing discord in homes and families, since she attracted or seduced men, especially married men (Leal, 1982). In addition, she assumed the role of prostitute and party girl, as she used to be a character who frequented cantinas; the moral conflict with the mulatto caused her to be represented as disobedient, unruly and erotic.

María Dolores Ballesteros Páez argues that in some Cuban images from the xix (especially in painting, lithographs and engravings) the representation of the mulatto woman enclosed a sensual and sexual charge; likewise, in those same images white men used to appear who "fell before the charms of the mulatto woman" (2016: 46-47).

To mention some theatrical references in Yucatán is Coca, who, according to Juan Francisco Peón Ancona, was a Cuban mulatto who arrived as a singer in the Compañía de Zarzuelas de Alcatraz y Palou, a company that performed at the Teatro Peón Contreras in Mérida in 1885 (Peón Ancona, 2002). According to this same author, the wives described her as a "buscona", while for the men she was a beautiful and charming woman; with this we can observe the reproduction of the representations that circulated about mulatas, especially when it is mentioned that Coca had an affair with a married man named Gonzalo (Peón Ancona, 2002).

Another example of mulatto representation is Tundra, who, unlike Coca, was a character created for the theater play entitled Cinco minutos con Tundra. The script has no date or author, but is classified in the Biblioteca Yucatanense de Mérida as a theatrical piece belonging to the Yucatecan drama of the century. xx.9 In the play, two married men try to trick their wives into going to see Tundra, a Cuban mulatto woman who, according to the script, attracted all men, married or single, with her sensual dances. Tundra was performing in the Yucatecan capital, so the characters went to great lengths to meet her, even if they had to lie to their wives in order to do so.

The character of Tundra recovers the negative values associated with mulatto women. She was perceived by Merida women as a danger to men, because this "rumbera de fuego" dazzled the male sex, "atundra", said one of the wives of the protagonists. Thus, sensuality and eroticism in its representation were accompanied by conflicts and confrontations with the female gender (see image 6).

It is worth adding that another space for fun and entertainment that used representations of "lo negro" in Mérida was the carnival,10 the stage of the streets. There it was usual to see troupes composed of black characters such as the "Negro Catedrático", who, like the congo, was originally from the Cuban buffo theater.

The catedráticos represented the aspirations of these groups to resemble and be part of white society; for this reason they used ostentatious words in their speech, appeared elegant in their dress, and in general rejected their African past. Ironically, in their attempt to imitate white people, the black professors ended up being the mockery of the black muzzals, their opposites, and also of the white sectors themselves, who laughed at the sight of a supposedly civilized and educated black man according to European standards (Frederik, 1996) (see image 7).

Image 7. Representation of the black professors (Leal, 1982, set of images between pages 67 and 69).

Finally, the presence of "the black" in this context can also be traced in the so-called popular characters, as Francisco Montejo Baqueiro (1986)11 recorded in the stories about them. Some of the names of the characters that appear in Montejo Vaqueiro's list are the following: Félix Quesada, alias Macalú, a bullfighter; Benito Peñalver, who possessed musical abilities to sing; Tomasito Agramonte, owner of a brothel; Negro Crispín, who because of an intellectual disability believed he was sent by the god Neptune and could predict the rains; José Godínez Crespo, alias Timbilla, who suffered from a motor disability that forced him to use a cane, which is why it was common to find him drunk and hear him blaspheming against God. There are even records that speak of Miguel Valdés (Negro Miguel) as a theatrical character who appeared in Yucatecan plays, having his own danzón inspired by the sale of ice cream, which was his trade (Montejo Baqueiro, 1981; Civeira Taboada, 1978).

It is important to mention that thanks to the description of these people it is possible to classify them in some of the representations that were made of "the black" and that were previously mentioned. To give some examples, Macalú represented strength and vigor, characteristics associated with African groups since the colony, when they came to fulfill slave functions; Peñalver possessed the capacity to entertain and, in general, musical gifts; on the other hand, Timbilla showed aggressiveness, alcoholism and being a troublemaker, elements of the black cheches or curros (also of the Cuban bufo).

Then, whether in theater, carnival or popular type stories, these characters assumed representations that pigeonholed and reduced "the black" to a few ideas and images, stereotyping Afro-descendant populations and groups throughout the Western world, by embodying and reproducing them also in various platforms of popular culture: television, cinema, theater, music, literature, propaganda and advertisements for food and other products (Nederveen Pieterse, 2013) (see image 8).

It is important to emphasize that all these representations of "the black" in Merida arise, on the one hand, from socio-cultural exchanges with the Hispanic Caribbean (Cuba, mainly), with the United States (New Orleans, for example) and with Western Europe (France, England, etc.); on the other hand, the origin goes back to the scientific racism of the end of the 20th century. xixideology that conceives differences in deterministic terms (Guillaumin, 2008).

This way of thinking, which permeated Mérida at the beginning of the century xxtried to justify the ideas and images that were held about the black population using apparently scientific bases. With such arguments, if the negrito was represented as a cheerful character, dancer, comedian, alcoholic, gambler, lewd, etc., it was because biologically it was believed that this was his nature; and the theatrical environment of the city helped to spread this perspective.

Racism as a discourse that naturalizes difference took root during the 20th century. xx under the conception that the physical and cultural attributes of human groups could be an object of study for the natural sciences, such as biology, and for the social sciences, such as anthropology and sociology. Thus, Herbert Spencer "emphasizes the fixed characteristics of race that authorizes, according to him, a racial group to maintain itself through struggles by eliminating impure specimens" (Wieviorka, 2009: 27). In such terms, scientific racism would postulate that cultural superiority supposedly resided in the white race, while the others fell into savagery and barbarism, thus marking the difference between the civilized and the uncivilized (Wieviorka, 2009). Precisely in that second group was included the black population, whose representations in the theater showed ignorance, savagery and exoticism; it is worth remembering that the congos and bozales were the characters that encompassed those elements.

Regarding difference, Stuart Hall says that within the process of representation lies an interest in delimiting the differences between self and otherness, an interest that lies in assigning meaning to things, people, places and events (Hall, 2010). In this sense, in Yucatan "the black" was associated with the foreign, with the "other" and not with the regional culture and history, despite the fact that these groups were present in the territory since colonial times.12 and even in the city's theater scene.

There, on stage, the negrito and the mulata assumed a Cuban foreignness that differentiated them from the Yucatecan identity, but at the same time the social, economic and cultural links between Cuba and Mérida were implicit, elements that the regional theater of Yucatán itself had assimilated (see images 9 and 10).

Representing involves belonging to a social group in which values, norms, ideologies and behaviors are shared, causing representations to consolidate a national or regional identity and at the same time mark a difference with those who do not share those representations (Rateau and Lo Monaco, 2013). For this reason the representations of "lo negro" in Mérida transited through the theater and among the different inhabitants who accepted and became familiar with the ideas and images we have mentioned so far; an example of this are the illustrations that accompanied newspaper propaganda and advertising (see image 8).

Hall also argues that it is by contrast that we usually generate meanings; we give shape and meaning to reality by delimiting what is our own from what is not, as a kind of tool that makes the environment more familiar. In the Yucatecan theater of the beginning of the century xxThe negrito and the mulata were characters catalogued as foreigners because they differed from the Mayan Indian and the mestizo, characters that were constructed as typical in the Yucatecan regional genre. I consider that this exercise of contrasting was nourished by the regionalist posture in Yucatan (Taracena, 2010), as well as by scientific racism.

The problem is when the differences by opposition become too reductionist or simple, which ends up stereotyping that which is represented. For Hall, the relationship between stereotype and representation lies in the fact that the former is a way of creating meaning in the world, resorting to exaggeration, segmentation and the use of essential and apparently fixed features in nature (Hall, 2010). Therefore, in order to understand the world, people make use of stereotypes to make sense of reality, to understand it; likewise, they are built collectively and by consensus, since repetition favors their anchoring in the social space (Ghidoli, 2016).

Then, following the approaches of Hall (2010) and María de Lourdes Ghidoli (2016), stereotypical representations of the negrito and the mulata took root in the theatrical scene of Mérida, reducing Afro-descendant populations (Afro-Cubans, above all) to certain exaggerated and pre-established features and elements. And to achieve the anchorage, the repetition derived from the multiple Cuban theater companies that visited the Yucatecan capital, as well as from the Meridanos themselves who characterized themselves as negritos in the plays or for the carnival comparsas.

When difference comes into play and we feel alienated from that which we represent, a relationship of power is born, a symbolic power, since "the other" is molded according to the perspective of a particular individual or group. In this regard, Hall states that power "has to be understood here not only in terms of economic exploitation and physical coercion but also in broader cultural or symbolic terms, including the power to represent someone or something in a certain way within a certain 'regime of representation'" (2010: 431). In this struggle to establish one's own culture and ideas over external ones, stereotypes emerge as a sample of the power that resides in representations, as they reduce the "other" to a few physical, cognitive, moral and behavioral traits to make them static and immovable (Ghidoli, 2016).

Thus, the stereotypes assigned to the negritos and mulatas were the result of an exercise of power towards a population historically subjected in socioeconomic terms, but also in cultural terms. The circulation of such representations meant the imposition of physical, cognitive, moral and behavioral elements from the vision of a society that was not part of the groups it was pigeonholing and that, in addition, saw them from the seats of the enclosure, applauding the shows, but marking a distance and difference between them.

In the end, while the establishment of differences is useful for the production of meaning, the formation of language and culture, it is still "threatening, a site of danger, of negative feelings, of cleavage, hostility and aggression towards the Other" (Hall, 2010: 423). This helps us to understand the oblivion and invisibilization suffered by the negritos and mulatas in the theatrical productions of Mérida today, including in the collective memory of Yucatecan society (Cunin, 2010).

In response to the research question,13 the appearance of the negrito and the mulatto character at the beginning of the 20th century. xx is linked to the close artistic, cultural, socio-political and economic relations between Cuba and Yucatán, which we can reconstruct through the circulation of artists and the arrival in Mérida of the negrito troupes and their performances. This circulation of representations of "the black" in Yucatan, seen in the theater, implies a process of assimilation of historically and culturally decontextualized ideas that gave shape to stereotyped and essentializing representations.

I also believe that the regionalist ideology, which began to gain momentum in the 1920s, has been a key factor in the development of the region. xxas well as the scientific racism of the end of the 20th century. xixThe fact that the mestizo Mayan-Spanish characters were gradually abandoned in favor of the mestizo Mayan-Spanish character, who became the typical character of Yucatecan regional theater, differentiating himself from those who occupied the place of foreigners and were left out of the Yucatecan identity, explains part of the progressive abandonment experienced by the black and mulatto characters.

To conclude, we can argue that the city of Mérida at the beginning of the century xx was a place where different representations of "the black" circulated and converged, being the artistic and entertainment sphere one of them. Thus, the Yucatecan theater became familiar with and accepted, even if only on stage, characters such as the negrito (congo or catedrático) and the mulata rumbera, who arrived thanks to the vernacular theater of Cuba (bufo). minstrel14 The United States and a whole series of Western representations that stereotyped and limited the perception of Afro-descendant populations.

This is how questions and questions arise when studying Yucatecan regional theater today, especially when we observe that foreign characters such as the negrito no longer appear in modern plays that are staged, falling into a situation of oblivion and ignoring those times when their theater companies were applauded and even when they walked the streets of the city.

In short, invisibilization and the use of stereotyped and naturalized representations are social processes that are part of Merida's theatrical and entertainment history, where black characters were reduced to certain physical features, attitudes and behaviors, with the purpose of constructing meanings, yes, but also due to certain racist ideologies that permeated the era.

Thanks to the cultural and ideological circulations, as well as to the representations of "the black" that moved in other media and contexts, the negrito companies were nurtured to create characters that were presented on the Yucatecan stages, where the public ended up identifying them as foreign and alien to the regional, but also from a marginal sense that led to their gradual oblivion and invisibilization.

In general, this is a topic that can still continue to be worked on and investigated, not only in the context of the Yucatan Peninsula. I believe it is important to continue identifying the representations of "the black" today and their historical origins, to demonstrate the existence and presence of these groups and above all to question the reason for their apparent disappearance from the scenarios and social memory.

Bibliography

Arredondo, Enrique (1981). Enrique Arredondo (Bernabé). La vida de un comediante. La Habana: Editorial Letras Cubanas.

Ballesteros Páez, María Dolores (2016). “Los afrodescendientes en el arte veracruzano y cubano del siglo xix”, Cuadernos Americanos, núm. 156, pp. 33-60.

Burgos Carrillo, Alejandra Liliana (2014). “De la escena yucateca al pueblo: José ‘Chato’ Duarte. Teatro regional yucateco. Inicio siglo xx”. Tesis de licenciatura en Literatura Latinoamericana. Mérida: Facultad de Ciencias Antropológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.

Cervera Andrade, Alejandro (1947). El teatro regional de Yucatán. Mérida: Imprenta Guerra.

Civeira Taboada, Miguel (1978). Sensibilidad yucateca en la canción romántica. Toluca: Gobierno del Estado de México/Dirección del Patrimonio Cultural y Artístico del Estado de México.

Cunin, Elisabeth (2009) “Negros y negritos en Yucatán en la primera mitad del siglo xx . Mestizaje, región, raza”, Revista Península, vol. 4, núm. 2, pp. 33-54.

Farr, Robert (1983). “Escuelas europeas de psicología social: la investigación de representaciones sociales en Francia”, Revista Mexicana de Sociología, vol. 2, núm. 4, pp. 641-658.

Figueroa Magaña, Jorge (2013). “El país como ningún otro: un análisis empírico del regionalismo yucateco”, Estudios Sociológicos, vol. 31, núm. 92, pp. 511-550.

Frederik, Laurie (1996). The Contestation of Cuba’s Public Sphere in National Theater and the Transformation from Teatro Bufo to Teatro Nuevo: or What Happens when El Negrito, El Gallego and La Mulata Meet El Hombre Nuevo. Chicago: University of Chicago/Mexican Studies Program/Center for Latin American Studies.

Fumero Vargas, Patricia (1996). Teatro, público y estado en San José, 1880-1914: una aproximación desde la historia social. San José: Universidad de Costa Rica.

Ghidoli, María de Lourdes (2016). “La trama racializada de lo visual. Una aproximación a las representaciones grotescas de los afroargentinos”, Corpus, vol. 6, núm. 2, pp. 1-11.

Guillaumin, Colette (2008). “Raza y naturaleza. Sistema de las marcas. Idea de grupo natural y relaciones sociales”, en Elisabeth Cunin (ed.). Textos en diáspora. Una antología sobre afrodescendientes en América. Ciudad de México: inah/Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos/Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, pp. 61-92.

Hall, Stuart (2010). Sin garantías: trayectorias y problemáticas en estudios culturales. Popayán: Envión Editores.

Hansen, Asael y Juan Bastarrachea (1984). Mérida. Su transformación de capital colonial a naciente metrópoli en 1935. Ciudad de México: inah.

Leal, Rine (1982). La selva oscura. De los bufos a la neocolonia. La Habana: Editorial Arte y Literatura.

Montejo Baqueiro, Francisco (1981). Mérida en los años veinte. Mérida: Maldonado Editores.

Muñoz, Fernando (1987). El teatro regional de Yucatán. Ciudad de México: Grupo Editorial Gaceta.

Nederveen Pieterse, Jan (2013). Blanco sobre negro. La imagen de África y de los negros en la cultura popular occidental. La Habana: Centro Teórico Cultural.

Peón Ancona, Juan Francisco (2002). Chucherías meridanas. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida.

Pérez Montfort, Ricardo (2007). “De vaquerías, bombas, pichorradas y trova. Ecos del Caribe en la cultura popular yucateca 1890-1920”, en Ricardo Pérez Montfort (ed.). Expresiones populares y estereotipos culturales en México. Siglos xix and xx. Diez ensayos. Ciudad de México: ciesas, pp. 211-250.

— Christian Rinaudo y Freddy Ávila Domínguez (coords.) (2011). Circulaciones culturales. Lo afrocaribeño entre Cartagena, Veracruz y La Habana. México: ciesas/ird/Universidad de Cartagena/afridesc.

Rateau, Patrick y Grégory Lo Monaco (2013). “La Teoría de las Representaciones Sociales: orientaciones conceptuales, campos de aplicaciones de métodos”, en Revista ces, Psicología, vol. 6, núm. 1, pp. 22-42.

Taracena Arriola, Arturo (2010). De la nostalgia por la memoria a la memoria nostálgica. El periodismo literario en la construcción del regionalismo yucateco. Ciudad de México: unam.

Tuyub Castillo, Gilma (2005). El teatro regional yucateco. Mérida: Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán/icyConaculta/pacmyc.

— (2010). Recuerdos de teatro. Entrevistas a personalidades del teatro regional. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida/Dirección de Cultura/Fondo Editorial del Ayuntamiento de Mérida.

Valencia Abundiz, Silvia (2007). “Elementos de la construcción, circulación y aplicación de las representaciones sociales”, en Tania Rodríguez S., M. L. García Curiely D. Jodelet (coords.). Representaciones sociales: teoría e investigación. Guadalajara: Centro Universitario de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades/udg, pp. 51-88.

Villegas, Juan (2005) “Desde la teoría a la práctica: la escritura de una historia del teatro”, en Osvaldo Pellettieri (ed.). Teatro, memoria y ficción. Buenos Aires: Galerna, pp. 43-50.

Wieviorka, Michel (2009). El racismo: una introducción. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Zayas de Lima, Perla (2005). “La construcción del otro: el negro en el teatro nacional”, en Osvaldo Pellettieri (ed.). Teatro, memoria y ficción. Buenos Aires: Galerna, pp. 181-194.

References

Fondo Reservado de la Biblioteca Yucatanense

La Revista de Mérida, enero de 1895.

La Revista de Yucatán, noviembre y diciembre de 1918 y enero a febrero de 1919.

Diario de Yucatán, octubre de 1930 y octubre de 1943.

Diario del Sureste, octubre de 1943.

Fondo Reservado, Libreto TPR-010, título Cinco minutos con Tundra, sin autor, sin fecha.

Photographs

Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Facultad de Ciencias Antropológicas, Fototeca Pedro Guerra, Fondo Pedro Guerra. Propagandas comerciales, sin título, clave digital 4A012024.jpg.

Luisangel García Yeladaqui holds a degree in Humanities from the Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo (Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Quintana Roo (uaeqroo) and master's degree in History from the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, Peninsular branch. He has worked as a lecturer in the uaeqrooShe teaches history subjects in the Bachelor's Degree in Humanities. She currently works at the Centro de Actualización del Magisterio de Chetumal as a teacher in the Bachelor's Degree in Teaching and Learning of History, in which future history teachers are trained. It should be added that the present article is the result of her research thesis carried out during her Master's degree in History at the ciesas Peninsular