From the portrait to the selfie wixárika: A visual history of ours

- Sarah Corona Berkin

- ― see biodata

From the portrait to the selfie wixárika: A visual history of ours

Received: January 23, 2018

Acceptance: June 3, 2018

Abstract

In the framework of discussion on the multiple visual cultures, I describe the self-portraits that an indigenous community takes and the selfies twenty years later, from the arrival of the smartphones. Based on a selection from the archive of 6,000 photographs taken by young Wixaritari, I seek to raise questions about visual cultures in the plural and their relationship with western and hegemonic visual culture.

Keywords: historical photograph, indigenous photography, the inverted look, photographic portraits, selfies

From Portraits to Selfies. A Huichol Visual History

Within the framework of discussions on multiple visual cultures, I describe self-portraits an indigenous community makes of themselves as well as the selfies its members take twenty years later, now that smartphones have reached their population centers. Based on selections from a 6000-print archive young Huichols assembled, I posit questions regarding visual cultures (in plural) and their relationship to Western and hegemonic culture.

Keywords: historic photography, indigenous photography, photographic portraits, selfies, the inverted gaze.

Pteach in plural visual cultures1 It offers us an opportunity to understand the images made from other visual cultures in dialogue with Western visual culture and at the same time allows us to understand our images in dialogue with those of multiple visual cultures. I call this double operation, that of looking at the other and at oneself, "the reverse look" (Corona 2011), and we call the archive of the photos that the Wixaritari make of themselves in a span of twenty years "our history. visual".2 Although I understand that it may seem audacious to analyze Western culture from the photographs that another culture takes, I agree with Belting (2012) when he states that in this way a mutual clarification can be achieved. I consider here that the indigenous gaze, defined by their visual environments, shows its difference, but also shows, in the transformations through time, our western gazes traversed by visual technologies.

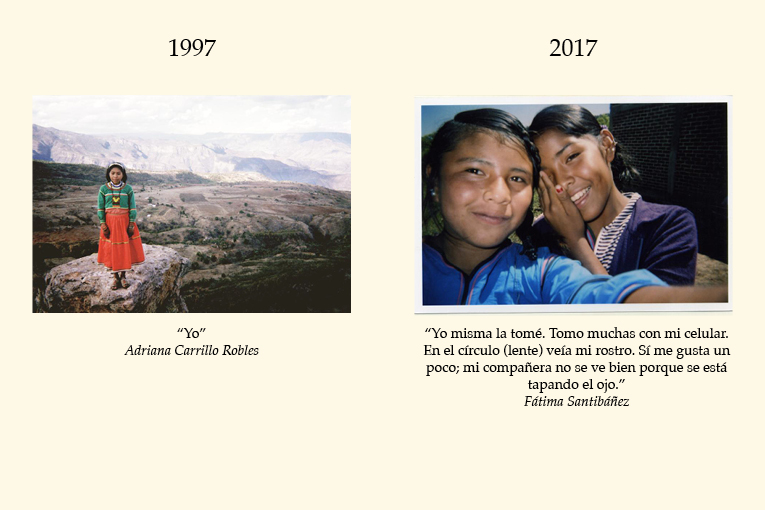

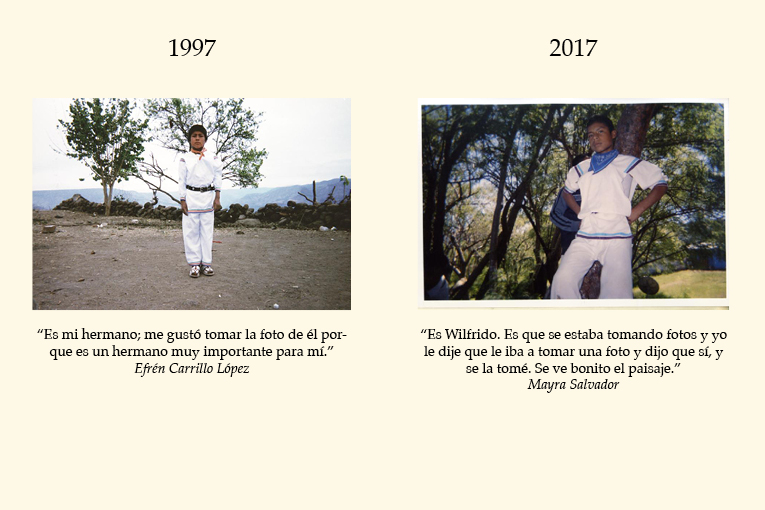

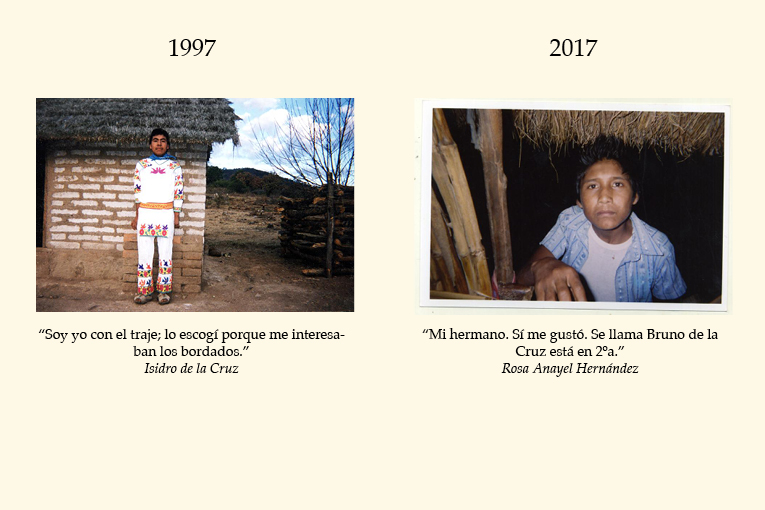

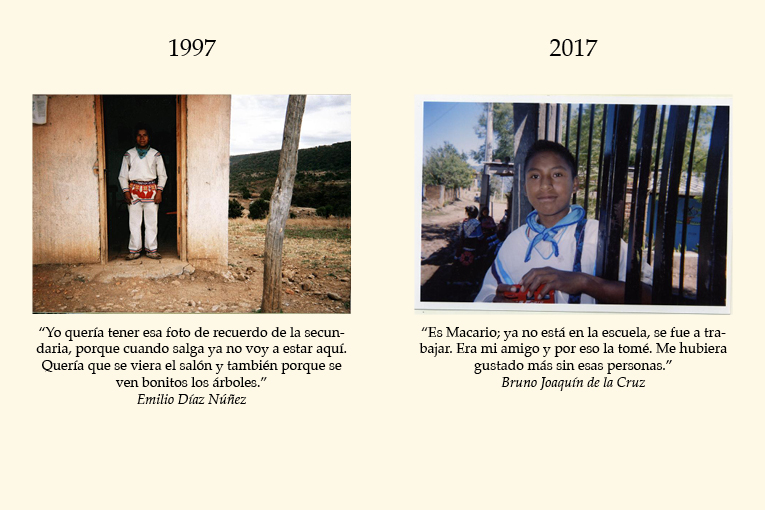

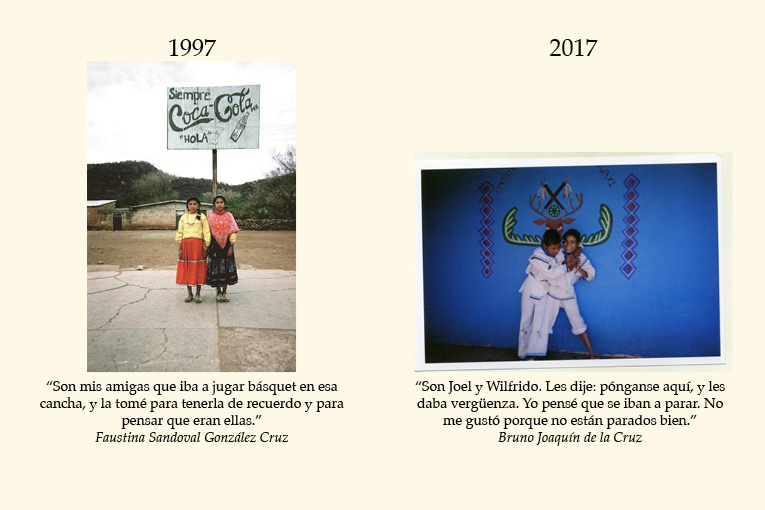

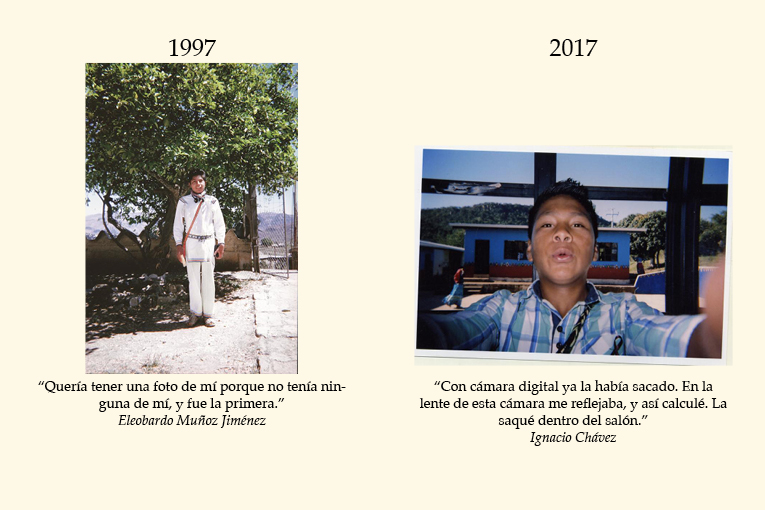

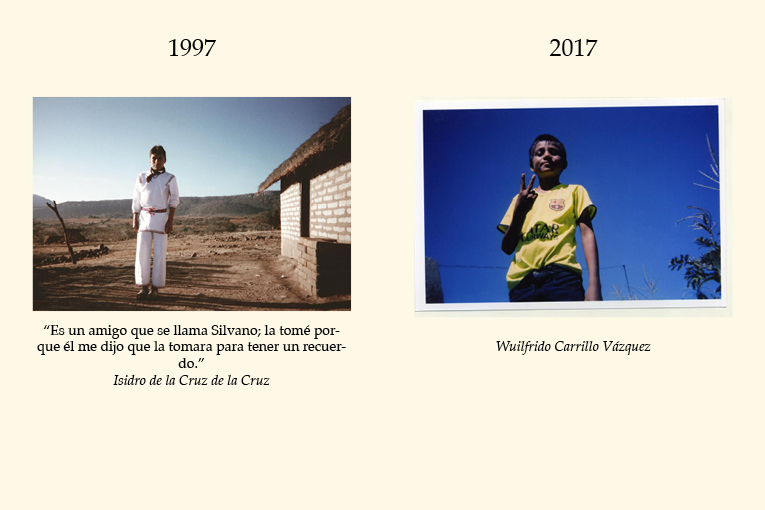

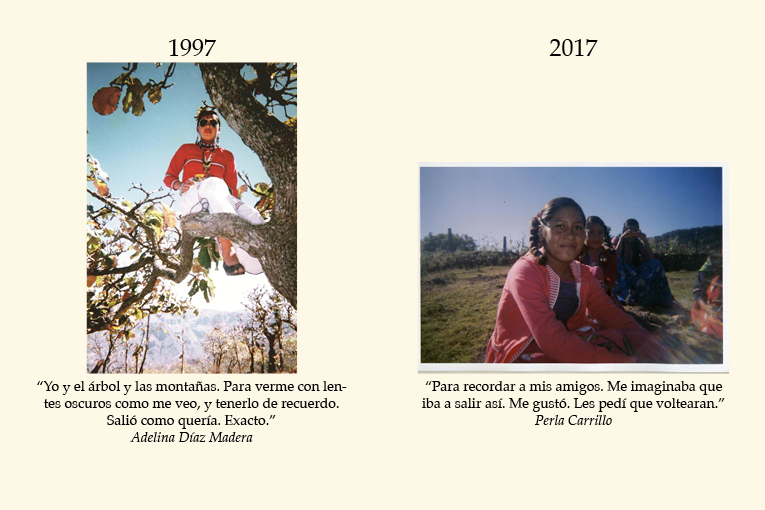

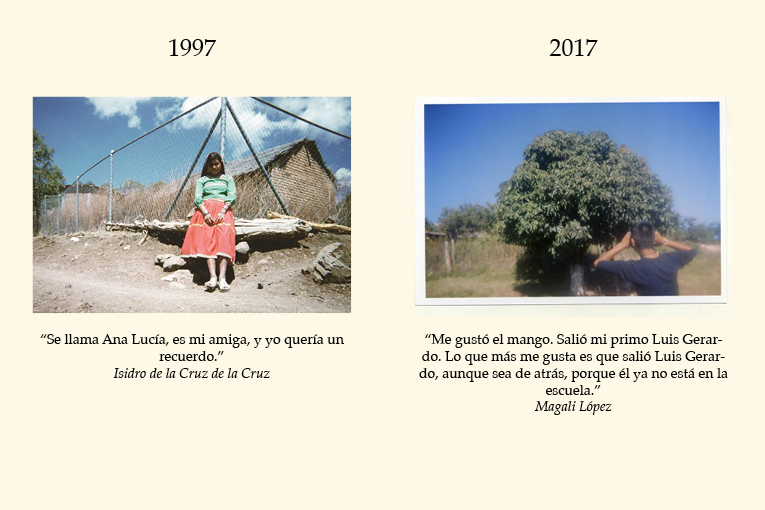

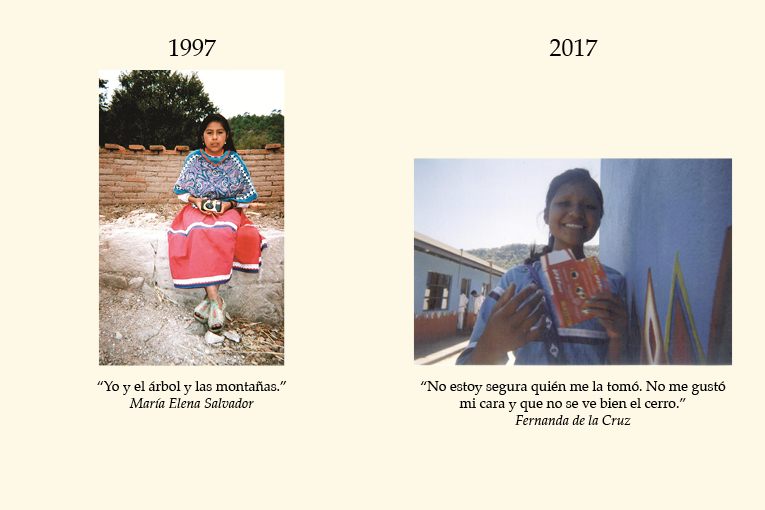

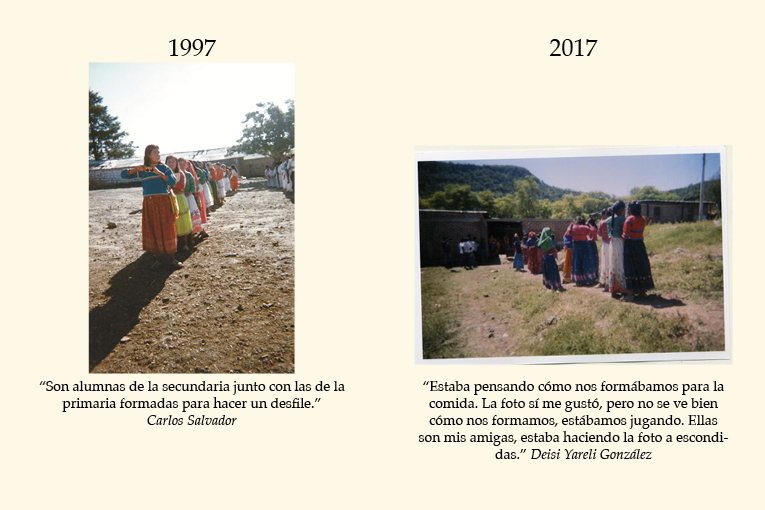

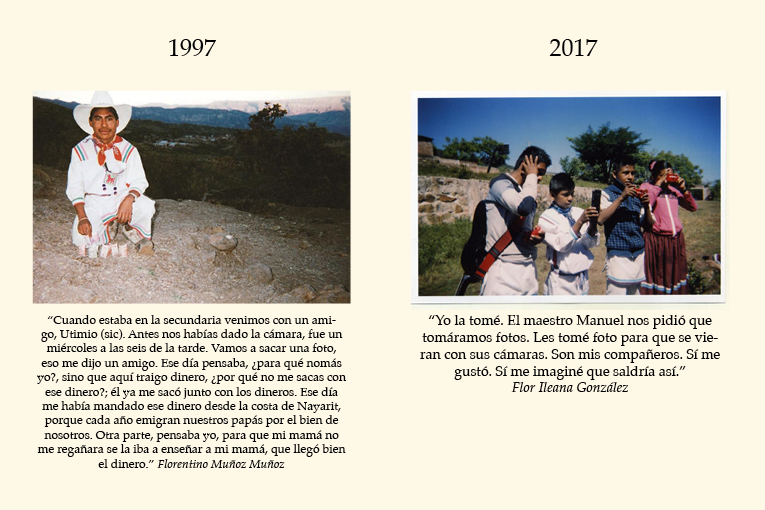

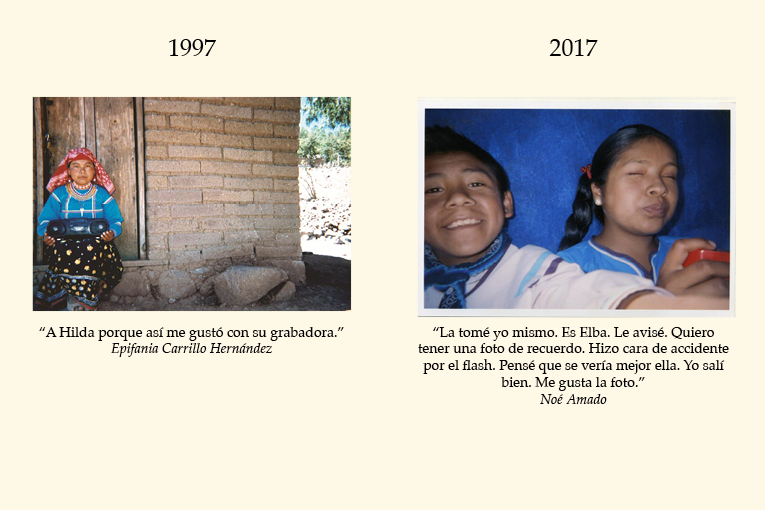

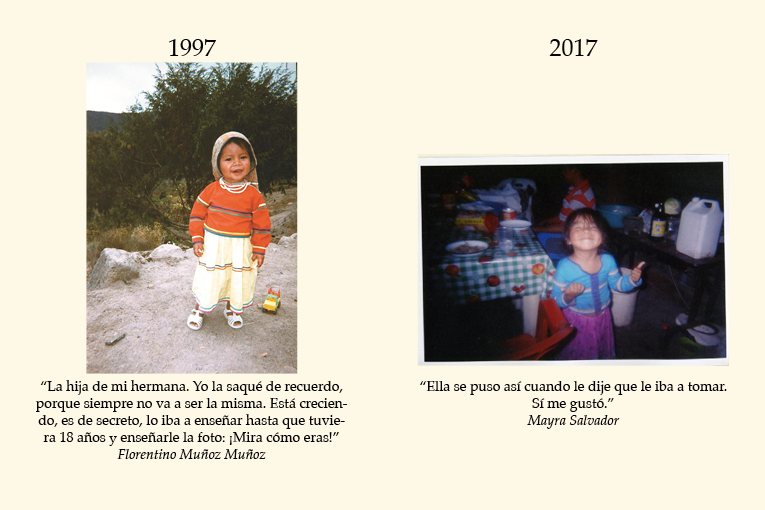

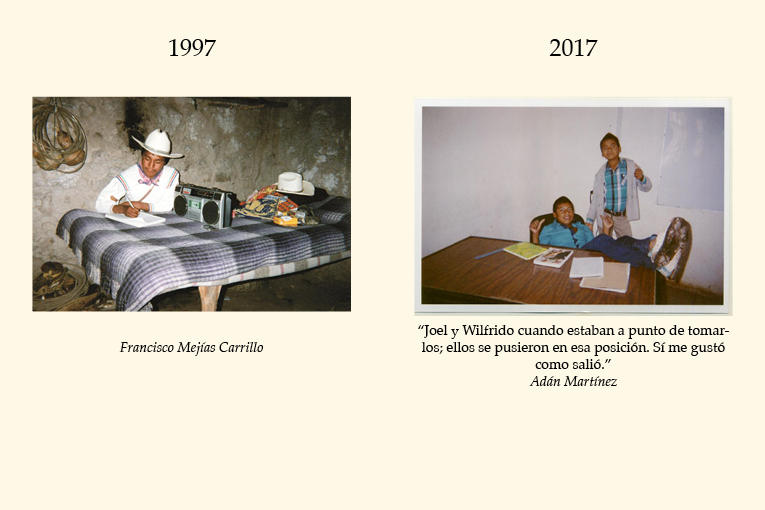

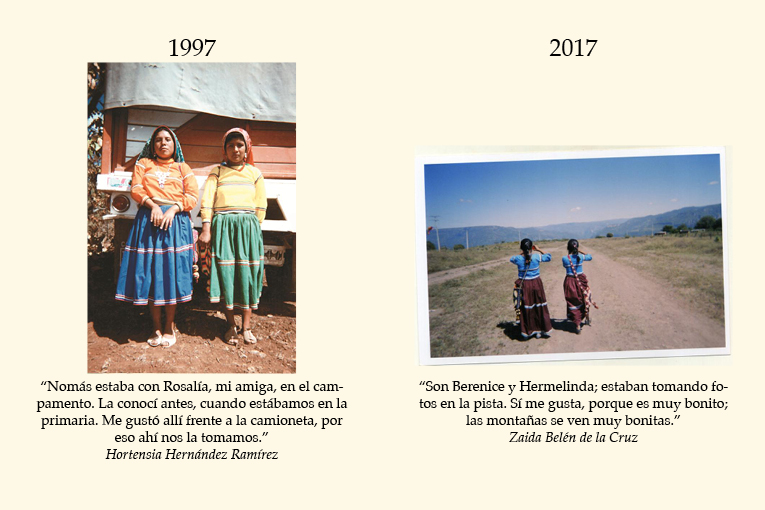

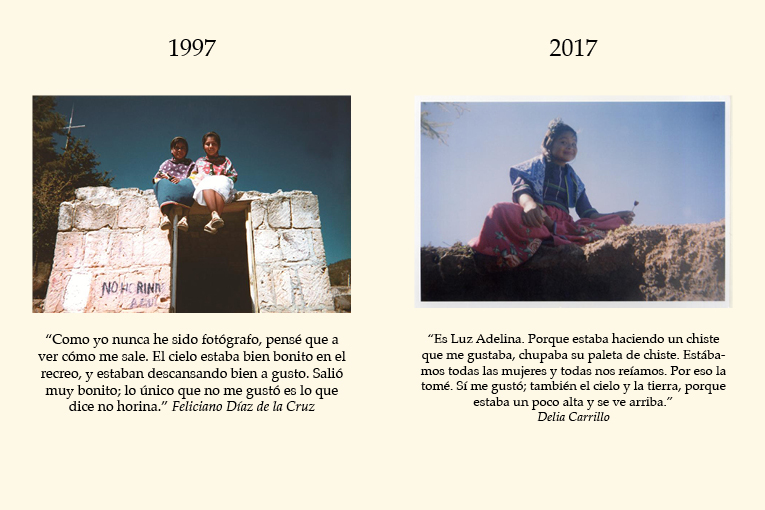

I propose as an example of visual cultures in the plural, and of the inverse gaze, the description of the indigenous photographic gaze in two moments: a first time, from the photos taken by young first photographers in a context far from photography western, and twenty years later, taking up the photographs taken by young people from the same community, but this time experienced in the photo selfie.3 With the corpus From photographs taken by young Wixaritari, I intend to show that there is a different way of naming the indigenous in images when they photograph themselves, and on the other hand, I seek to describe the changes that the gaze experiences through visual technologies.

From self-portrait to selfie

The contribution of a visual history such as the one that is built in this place from the photos taken during twenty years in an indigenous community is enhanced when it is not exclusively used for a community, but built from that community, it provides mutual knowledge. and dialogical for other cultures. The photographic work that I present has these two characteristics: it is an archive of the photographs taken by the indigenous Wixaritari, a name by which they themselves wish to be known, and at the same time it offers us an understanding of our own western visuality traversed by photographic technology. His visual history is a political contribution to the inclusion of all from his own perspective, and it is also a contribution to the social knowledge of Western culture.

“Our visual history” is the name we have chosen for the private collection of almost 6,000 photographs collected from 1997 to 2017, all taken by young Wixaritari with their own single-use cameras, without prior instruction in Western photographic language. The only warning given to the young photographers was to appear in the portraits as they wish to be seen by their community and beyond.

Unlike visual anthropology, where the photo is used above all to corroborate the presence of the researcher in the field and as an auxiliary tool for detailed description (Gamboa, 2003; Flores, 2007), an objective of its discipline, and also differently of the indigenous photographic artists who, although they expose their own face, is that of the individual author, in this project, through the photos, we try to achieve the autonomy of their own gaze (Corona, 2012). In this place we start from a first description of the shots or plans and the themes of the collection, in order to carry out an initial classification of the material.

It was a year ago, at an academic meeting at the headquarters of the University of Guadalajara located in Colotlán, that by chance I ran into a young Wixárika student who was studying law there. The young man presented to me the need he saw to "complete our visual history." He told me: "You have the photos that the Taatutsi Maxakwaxi students took years ago, but now they have changed a lot." He added: "Today they have cell phones and they take lots of photos with them."

Their invitation to “complete” the visual history of several generations of young people from the San Miguel Huaixtita High School and their express request attracted me to the archive that I have kept of the first photographic experiences of these young people: 2,700 photos taken in 1997 (Corona, 2002) and 837 made in 2007 (Corona, 2011). Today, adding the 2 379 of 2017, there are a total of 5 916 photographs in the collection.

The first photos of the young Wixaritari made in 1997, with almost no experience in the image since they had never taken a photograph before, because they were far from advertising, television, full-length mirrors, without contact with the cities and their surroundings visuals, acquire exceptional value for all of us. The second set of photos are those taken ten years later by students from the same high school, but during their first trip outside of their community. The cameras and their visual context were the same, but the result was different, as it was his first contact with a city. I will speak little of these photographs, since the objective is to compare the shots that were taken in the same place twenty years apart.

To fulfill the challenging task entrusted, twenty years after the first photographic practice and ten years after the trip of the young people to the city, I returned to the same school, with young people of the same age, from first to third year of secondary school. ; they were provided with the same type of single-use cameras. In January 2017, the 125 cameras were distributed to the students and teachers of the Taatutsi Maxakwaxi High School and their operation was briefly explained. Young people today, in a way, were also the first analog photographers, as their predecessors were of any type of camera. Although several young people from 2017 had already taken photos with a cell phone, they did not know about analog cameras. A young woman, showing her digital knowledge, asked: "where do you turn the camera on and off?", "Why only 27 photos?" The youths returned the cameras five days later to be taken to the city for development. A few months later I returned, as agreed, with a copy for each photographer, and conducted interviews with the boys from a selection from the set of photos.

Visual context of young photographers

The town of San Miguel Huaixtita has not changed much in twenty years; Still having fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, the Taatutsi Maxakwaxi Secondary School project, founded in 1996 as the first secondary school in the entire Wixárika area, has stood in favor of caring for and preserving the Wixaritari language and culture.

The big changes in twenty years? The official educational offer has grown: a primary school with a shelter was built by the Sep, and two new high schools were inaugurated in the town.

The light arrived in 2009, and with it the electricity poles appeared that gave a new appearance of the town. He also brought the televisions to watch movies and videos on the movie players, night light in the houses and on the streets. The dirt road that crosses the mountains and that connects San Miguel Huaixtita with the town of Huejuquilla el Alto, with 9 thousand inhabitants, was finished in 1998, after the first photographic experience. The first users of this road were beer and asbestos roofing trucks and illegal timber traders (Corona, 2002). Since 2000, and especially since 2004, the presence of drug trafficking has intensified throughout the Sierra de Nayarit, Jalisco and Durango, a phenomenon that goes beyond local limits and, as in the entire country, is related to networks international drug trafficking (Guízar Vázquez, 2009). Another change made by the municipality was to pave two main streets with cement, which prevents the passage of water to the subsoil and causes flooding during the rainy season. On the other hand, the health system worsened, the shortage of medicines increased, the low supply of seeds for the greenhouse program promoted by the government's welfare programs makes its usefulness precarious. Very few families have access to nearby cities, their consumer products and cultural assets. Different cults proliferate as always; Professor Carlos told me in the past: “our souls must be very valuable because so many religions fight for them”. Their own rituals endure, although they are tolerant of some Catholic practices in their own way. Corn is planted and those who have cattle produce cheese during the rainy months. Twenty years ago it was said that the most prosperous Wixaritari were the cattlemen, today they are the merchants who have shops in the community, and those who approach the different religions who arrive with productive projects and pay for lodging services, etc. Cattle have lost importance, as the Wixaritari have lost their importance due to the excessive increase in cattle theft. On the other hand, several of the young people who study high school in Taatutsi Maxakwaxi manage to enter university and return as professionals to the town or stay in the cities to work and are points of contact between their community and the city.

In short, for the majority of the inhabitants of San Miguel Huaixtita, the quality of life has not changed much, if we subject ourselves to well-being criteria such as income, mobility, access to national cultural assets, housing, and health.

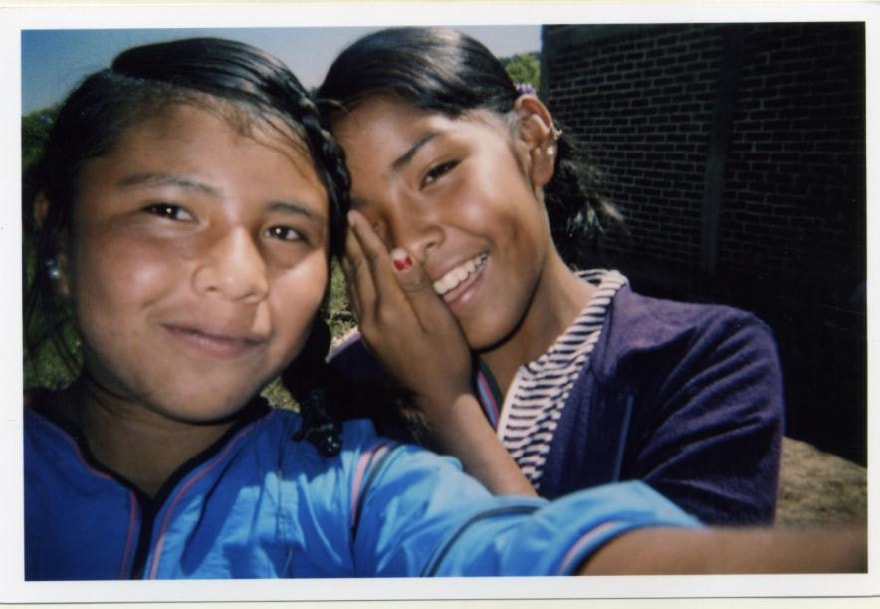

However, there is something that has undeniably been transformed and has a greater cultural impact: access to communication technologies. Although in San Miguel Huaixtita the use of these is moderate to communicate, because the internet is very limited and deficient, hiring antennas for television reception is expensive, not to mention that the cell phone signal is not frequent in the upper area of the Sierra Madre Occidental where the population is found. But young people in high school have technologies that have come from the cities and that transform the way they look. What has changed is the ability to watch television and the opportunity to snap and take photos. Especially young people are attracted to the new gadgets. Parents who have a cell phone mention that it is fun for young people to take photos making faces, tousled hairstyles, smiling, gestures, etc., and to erase all those they do not like. Those called by us selfies (never named after them) serve as a mirror that freezes the image and allows it to be analyzed by the young photographer-self-photographed. The photos are shown mainly on screen among young people, but they are not forwarded or shared on pages intended for this purpose, since they do not have a telephone signal, or internet, or email.

It is clear that not only the Wixaritari have changed in twenty years. The globalized Western visual context changed. I mention that the small single-use cameras of the Kodak brand used in 1997 have practically disappeared. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2012. The reason is said to have been that the digital camera displaced analog products and Kodak was not in business on time. Despite being the founders of the photo amateurThey did not bet on the digital cameras that today are imposed in everyone's life. Thus, the cameras that were donated by the fashionable factory in 1997 now do not exist, or are sold very expensive as nostalgic objects on e-bay and Amazon. I ended up buying the Chinese version of the cameras, which I found not without difficulty. The development was equally complicated. We were forced to develop the 120 single-use cameras in a specialist art photo lab, as commercial labs now only work with devices that instantly print digital files. We can say that the photographic technology of the smartphone it has forced the transformation of the global gaze.

In other words, the communicative transformation that defines the current situation of the inhabitants is similar throughout the world.4 The data in Mexico reveal that in 2016, 75% of the population in the country had a Smartphone,5 more than 60 million smartphones taking photos, sending written messages and receiving information of all kinds. In ten years, cell phones have tripled. In other parts of the world they are also concerned about its possible influence, coupled with the long tradition of television screens, cinemas, computers and other invasion of images that circulate in the city. But, how to understand the impact of vision technologies on the concrete visuality of the inhabitants? Evoking McLuhan, what does the cell phone camera mean as an extension of the sense of sight? How can we approach an answer based on the verification of empirical data? The young Wixaritari who have taken photographs for twenty years and are now dedicated to constructing in dialogue “Our visual history”, which is theirs and ours, are beginning to have some answers.

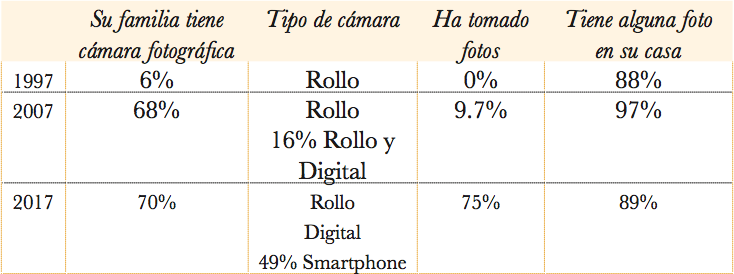

Prior to the three photographic shots, 1997, 2007, 2017, a survey was carried out to complete the data of their visual context, among others to confirm if they had taken photos with some type of camera and if they had their own and family photos. It was also asked if they knew of another urban population, in order to become aware of their exposure to the images that populate the public space of cities. Some answers are as follows.

With the preceding data, we can observe the increase in the presence of the camera and digital photography in the contexts of young people. When in 1997 only 6% of the young people had a family camera, in 2007 it had increased to 68%, and to 70% in 2017. The type of film camera remains the main type until 2017, since before this date it was they register only a few children with digital cameras in their family. In 2017 it can be observed that more than half of the cameras that children have are from cell phones. Although it was not requested, the responses of the respondents include the brand of Smartphone they use: Sony, Alcatel, Lanix, Samsung.

We can observe a considerable increase in the photographic practice in San Miguel Huaixtita in twenty years: from an almost total absence of cameras and no photographic experience, by 2017 most young people have the opportunity to take photos and know digital photography. However, 30% of the school's students still do not have a camera and 25% have not taken any pictures either. In the photographs of these young people we see a continuity in the themes and shots of their predecessors from 1997.

In Our visual history we can see that technological change and the possibility of taking photos with smartphones it does not increase the number of photos saved. While only 6% of the young people had a camera in 1997, and not a single one had taken photos, 88% had a photo taken by his father, brother, or gift from an anthropologist or visiting traveler. Today, 70% of the young people have a camera and take pictures, and 89% (1% more than in 1997) have some pictures at home.

It is interesting to note that between 1997 and 2017 the number of families with photographs did not increase. On the contrary, it decreases between 2007 and 2017, in contrast to the increase in cameras in 2007, and especially in 2017. We can infer that the decrease in the number of photos preserved has to do with digital technology, not only in use in the Wixárika community, but by the visitors who previously brought and gave the photos during their visits. It could be that the increase in preserved photographs is not proportional to the increase in photographic cameras because digital photography has reduced the photos that are owned, due to lack of the necessary technology to store them - such as the cloud, or computers and memories with a large storage capacity , which are not possessed in the Sierra.

It is also the characteristic of the digital photo, where the deep meaning that was attributed to the few photos that were kept in the family album as witnesses of the past and family history has given way to the infinite images that are shared in real time. of daily activities.

The presence of the electronic means of communication is increasing. In 1997, screens were absent from the daily lives of young people, since none of them had a television or computer. In a progressive way, televisions and computers appear in the community. By 2007, people who owned televisions connected to paid antenna systems used to charge a fee to those who wanted to watch soccer, news and soap operas. Computers, introduced by the Sep in schools, they functioned with limitations due to the solar energy on which they depended, as well as the lack of training and the constant composure required. By 2017, half of the student population has a television at home and only 13% has no access to watch the television. TV. The computer is used in the classroom for that purpose, and some youth have computers at home.

The photographic shots

The photographic planes show in a more or less ambiguous way what the photographer wanted to say and what the reader of the photo can observe.6 The 1997 photographs were defined by their wide contexts and depth of field. His first 2,700 photos were taken in general shot, not a single close-up photograph was found; The theme of people in natural environments was favored, but the theme of nature and animals was also important. People always posed face-to-face, arms at their sides, looking at the camera. In the second experience, ten years later, their experience with the image had not changed substantially, they had more cameras and photographs in the community, but the visual context was similar: few products packaged with labels with images, few posters inside and outside the houses and at school. On the other hand, these photographs were taken during his first trip to a city. In 2007, in addition to being first photographers, they were first travelers. His photographs still struggled to capture the big shot, and his satisfaction grew the closer he got to a wide shot with context and depth of field. The tall buildings and the infinite closed spaces of the city forced them to photographs with less visual range. The complaints did not wait: “I wanted the whole [building] to be seen”, “I didn't like it because only the colleagues or the [building] were visible; I wanted them to see each other up to the top ”.

The distant shot in general can be analyzed as a tendency to distance and search for objectivity, fight against fragmentation and as an effect of reality. In the photos that make up Our visual history We observe an absolute decision to use the general plan in all their photos from 1997 and those of 2007. The general plan for them means “seeing everything”, “knowing where it is, what it is doing”, “making the hills look beautiful, trees, houses, stones ”. The context defines the importance of the photo and the subject that appears there acquires greater importance integrated into the general shot.

The median plane leads to the fragmentation of the object due to a certain proximity and the balanced presence between the closeness and the distance of the object. The midplane offers the balance of tensions between the near and the far. In the photographic shots of the city, the medium shot was often forced by urban spaces and was not always appreciated by the photographer. In the case of the Our visual history, young people have discovered in the recent shots of 2017 the medium shot, which can bring the gaze closer to faces and bodies without completely decontextualizing the image. The use of the midplane is the most favored in 2017, in contrast to the 100% of wide shots of other times.

Let's analyze the foreground. It is the scale where an element stands out on the background; the object is enlarged and close to the observer in the photograph. This plane allows the object to be thoroughly reviewed, and when it is a person's face it provides greater sentimental intensity by bringing looks, gestures and faces closer to inspection and recognition. In the most recent photos, the foreground appears for the first time, and although in a minimal percentage, it is noteworthy that they are self-portraits in the manner of the selfies. Before these, the photographs never fragmented the bodies of the people (Corona, 2002), they were always taken full-length and contextualized in general shots.

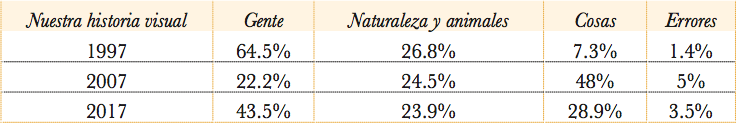

Photographic themes

Although the theme "people" exceeds the other themes in each of the three moments, we see that its presence decreases in Our visual history. The wixaritari photo archive shows a moderate interest in the subject of people when compared to the camera in the hands of the first photographers in France, where it already represented the 74% of people (Bourdieu, 1979). In Our visual historyIn 2007, the date of the lowest appearance of the topic people, young people say they are interested in the people they know; therefore, the photographs of people in the city are very few. "We are not interested in people we do not know," says a young man on his first trip to the city. The pedestrian crossing the street does not deserve a photograph, except if it shows a different appearance: “we had never seen a person sitting in a wheelchair”, “the lady did not interest me, it was the heels… then I bought some”, “those They hugged each other for a long time and stayed that way, they did nothing more ”, the young people comment on their photographs. In the other cases, the photographs of people are compensated by his interest in photos of nature and animals. In the most recent shot, the young people once again photographed themselves in their community. Photos of people increase compared to those taken in the city. The portraits, however, are in medium shots and close-ups.

The topic "things" fluctuates between 48% and 7.3%. In this topic, a documentary use of the camera is clearly observed when photographing its surroundings during its trip to the city in 2007, which is why the number of photos of “things that catch our attention because we do not know them” increases, “to show them to our family who have not seen it ”. In 2017, the things photographed, although they are from their community, are not especially those of their ancestral culture, but they show what is modern in the photos (posts, streets, houses, water tanks).

What new understanding do we rescue from our visual history? Between the looks and the visual technologies, visual changes appear that do not have to do with instrumental uses of communication technologies, but rather become structural in visual cultures. Image technologies today refer to new forms of vision, therefore to "new modes of perception and language, to new sensibilities and writings" (Martín Barbero, 2006). Visualities as cultural practices are not static, they are languages that are executed in a historical moment and that are always put at risk in front of others. To stop conceiving photography as substance, as purity that distinguishes the other, and rather to be inclined to think of it as a state of speech in dialogue with other speech, helps us to understand why photography is not a stable code: it determines the speakers, but it also transforms those codes, modifies them and produces new visual statements.

It remains for us to ask ourselves: will the Wixárika gaze and ours be impoverished by losing the context of the wide shots, in the new trend for close-up photos? Will the Wixaritari achieve a new dialogical way of being portrayed that does not assimilate them to the western photography of the hegemonic close-up? How will your visual practices modify your visual culture? It is in the shots and themes where this collection is appreciated as an exceptional material to understand visual cultures in the plural and our own western gaze. Our visual history it reveals not only the dynamism of the visual culture of the wixárika, but the history of our own vision determined by the technological-visual environment in which we live.

Bibliography

Belting, Hans (2012). Florencia y Bagdad. Una historia de la mirada entre oriente y occidente. Madrid: Akal.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1979). La fotografía o un arte intermedio. México: Nueva Imagen.

Corona Berkin, Sarah (2002). Miradas entrevistas. Aproximación a la cultura, comunicación y fotografía huichola. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara.

— (2011). Postales de la diferencia. La ciudad vista por fotógrafos wixáritari. México: Conaculta.

— y O. Kaltmeier (2012). En diálogo. Metodologías horizontales en ciencias sociales y culturales. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Flores, Carlos Y. (2007). “La antropología visual: ¿distancia o cercanía con el sujeto antropológico?”, Nueva Antropología, vol. 20, núm. 67, pp. 65-87.

Gamboa Cetina, José (2003). “La fotografía y la antropología: una historia de convergencias”, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, vol. 6, núm. 55, p. 1.

Guízar Vázquez, Francisco (2009). “Wixaritari (huicholes) y mestizos: análisis heurístico sobre un conflicto intergrupal”, Indiana, núm. 26, pp. 169-207.

Martín Barbero, Jesús (2010). “Comunicación y cultura mundo: nuevas dinámicas mundiales de lo cultural”, Signo y Pensamiento, vol. 29, núm. 57, julio-diciembre, pp. 20-34.