The dynamics of salvation goods in the cult of Jesus Malverde: A photographic essay on popular religiosity in Mexico.

- Arturo Fabian Jimenez

- ― see biodata

The dynamics of salvation goods in the cult of Jesus Malverde: A photographic essay on popular religiosity in Mexico.

Receipt: October 18, 2024

Acceptance: April 12, 2025

Abstract

This photo essay examines the production and dynamics of salvation goods in the cult of Jesus Malverde, a prominent phenomenon within popular religiosity in Mexico. During the annual May 3 festivity in Culiacán, these goods are especially visible and are continually renewed. The essay documents how the supply of these goods remains dynamic in a back and forth of traditions and innovations, adapting to the demands of the devotees and ensuring the validity of the cult in the Mexican religious market. Photographic observation captures the evolution of these practices and the diversification of salvation goods by showing how the cult of Jesus Malverde reinvents itself, making it relevant to the study of Mexican popular religiosity.

Keywords: salvation goods, cult of Jesus Malverde, freedom of religion, popular religiosity

salvation goods among Jesús Malverde worshippers: a photographic essay on popular religiosity in Mexico

This photographic essay examines the production and dynamics of salvation goods in the cult of Jesús Malverde, a popular religious figure in Mexico. On May 3, during the annual celebration of the "saint," the goods dedicated to Malverde are especially visible and continuously changing. The essay explores how the dynamic offer of goods reflects a constant interplay of traditions and innovations, adapting to the demands of worshipers to sustain the vitality of this cult on the Mexican religious market. Photographs capture how these practices have evolved and how the salvation goods have diversified, pointing to the reinvention of the cult of Jesús Malverde and its continued relevance in the study of religiosity in Mexico.

Keywords: religious freedom, popular religiosity, salvation goods, cult of Jesús Malverde.

Synergy

Popular saints have an increasing presence within the Mexican religious spectrum, not only by sharing space with the saints of the official cults, but also by accentuating their own traditions and innovations in the face of the broad religious market. This presence is achieved by mixing belief systems between the popular systems with the official and predominant belief systems of religious life in this country. In short, digital communication platforms have enhanced the presence of religious life on the Internet, which has facilitated the introduction of this type of characters in the virtual world.

In particular, the cult of Jesús Malverde -celebrated both by locals and by devotees from other parts of Mexico and even abroad- has become popular throughout the present millennium for his miracles and for being the saint of "drug trafficking" in Culiacán, Sinaloa; Jesus Malverde is also known for his relationship with Santa Muerte, St. Jude Thaddeus, St. Michael the Archangel (Cortés and Mancillas, 2007) and, more recently, with Elegguá, in addition to being recognized as an icon of Mexican popular culture. However, it is necessary to understand that the figure of the saint of drug traffickers has had different transfigurations throughout its history.

From anima to saint. The transfiguration of Malverde during his first hundred years in the Mexican religious market.

From a chronological point of view, Malverde was a martyr of Mexican liberalism who lived between the end of the 20th century and the end of the 20th century. xix and the first decade of the century xx. He was born in 1870, and it is believed that his name was "Jesús Mazo" (López-Sánchez, 1996). The character is described as an unfortunate orphan, son of the working class, who at a very young age began to work in the installation of the railroad that connected the Mexican northwest with the United States. Tired of injustice, after seeing his family die as a result of hunger and poverty, he decided to fight the oligarchy of the time, made up of local and foreign businessmen and the political class of Sinaloa.

Malverde was assassinated on May 3, 1909 by state forces, who were on his trail because the then "generous bandit" (López-Sánchez, 1996) had dedicated his life to robbing the bourgeois class to distribute the stolen goods among the poor. General Francisco Cañedo, then governor of Sinaloa, had been his main victim and it is presumed, in a mocking tone, that he stole a sword from his own house. After his murder he was hanged from a mesquite tree, since, according to the governor's instructions, his body did not deserve to rest in peace. It is presumed that even before being captured, he sent a relative to give reports on his location, which led to his capture and thus he was able to collect the reward and rob his enemy for the last time.

Soon after, after his remains fell to the ground under the mesquite tree from which he was hung (as the litany and the corrido say), a local farmer, who had lost a cow, asked Malverde to locate his animal in exchange for some stones to cover his remains as a tomb. Thus, it was no longer the generous bandit, but the bandit's soul that made such a reunion possible, which is why word spread about this miraculous event. In this way is that the soul of the young martyr, unable to rest in peace, wanders fulfilling miracles among the working class in the periphery of Culiacán in exchange for stones to complete his tomb (López-Sánchez, 1996; Cortés and Mancillas, 2007; Fabián, 2016).

The foundational myth points out that Malverde died on May 3, the day on which Catholics celebrate the Holy Cross in Mexico; therefore, since its beginnings, the cult to this character has been known by means of the holy cross of Malverde, which is described as a cross made with the steel beams used in the construction of the railroad tracks. It is necessary to remember that the celebration of the Holy Cross is related to the "day of the masons" in urban areas; however, in the countryside it has a closer meaning with the first rains of the agricultural cycle, while in different indigenous groups this celebration is related to cosmogonic events such as the alignment of Venus with other celestial bodies and their ceremonial sites. It is noteworthy that this date is not only relevant, but also has important religious meanings in Mexican belief systems.

The also called "horseman of Divine Providence" (Park, 2007; Gómez-Michel, 2009), not only returns to torment General Cañedo with his memory: by losing material properties, but gaining some spiritual ones, his soul is introduced to the Mexican religious market from this foundational myth. Over the years, the belief in the soul of a generous and miraculous bandit was transmitted -both in the Culiacán valley and in the Sinaloa highlands, among other less studied factors, such as the spiritualist churches in some regions of the country, idea that synergized with the legends of banditry of that time, particularly of social bandits such as Heraclio Bernal (Cázares, 2008), from whom various narrative elements are taken to feed the belief system around Malverde's life as a generous bandit (Lizárraga, 1998; Cortés and Mancillas, 2007; Fabián, 2016).

Hand in hand with the belief system are interwoven religious practices and displays of faith around the anima. The location of the mound of stones that represents the tomb of the generous bandit, together with a cross made with pieces of steel beam that were located next to the old train station of Culiacán, for more than six decades, are figures that allow maintaining a set of ritual and festive practices that began to be carried out around these two material objects; witnesses of the devotion of a nascent malverdista cult that is still present a few meters away from that place. With this, the foundational myth gradually acquired material properties related to the belief system and the religious and spiritual practices associated with the anima, which gave it greater legitimacy.

During my first approaches, an informant who grew up in the area recalled that approximately 60 years ago he attended the celebration that took place every May 3; there was only the cross of beams and a mound of sacred stones as a representation of the tomb of the soul of Malverde. The cross was decorated with banners and the festivity was attended by cab drivers, prostitutes and thieves, among others (Lizarraga, 1998). The face and his characteristic moustache and semi-populated eyebrow, the denim shirt and the big-bang style tie, came after a few years to form the "original" image of Jesus Malverde, the misnamed saint of drug trafficking.

Some immaterial elements among corridos and apocryphal prayers began to be dedicated and heard especially during the anniversary of his death among the adherents to the Malverdist cult, in which references to material objects and their function to provide protection, to thank for the fulfillment of some miracle, such as alleviating health ailments, pacts to which compliance is given by visiting the cross and carrying stones or some other type of offering (López-Sánchez, 1996; Cortés and Mancillas, 2007; Fabián, 2016).

At the beginning of the 1980s, the anima, following an administrative decision by the state government, was stripped of the territory and its objects. During the implementation of the reorganization of the area and the creation of the Sinaloa Center, in order to centralize different government agencies in the place, the mound of stones venerated by the small Malverdist community organized by Roberto González Mata was encapsulated inside a private parking lot, while the cross was relocated inside the new chapel, on land donated to them a few meters ahead (Lazcano and Córdova, 2002).

With the construction of the chapel and the passing of the baton from González Mata to don Eligio González, the cult entered a stage of consolidation and institutionalization of its belief system and some of its main religious practices; an organizational body was structured, responsible for administering the place and covering the bureaucratic needs required by a space of that nature (Fabián, 2016; 2019). Likewise, its members are responsible for the sale and distribution of sacralized objects such as votive offerings, candles, scapulars, rosaries, medals, garments and clothing accessories, etc. They also administer services that include spiritual cleansings, activation of amulets, blessing of sacralized objects, among others (López-Sánchez, 1996; Cortés and Mancillas, 2007; Fabián, 2016).

After the limitations imposed by the restructuring of the territory, they saw the need to produce new material supports for his cult; it was then when the transfiguration of the generous bandit recovered his physical features. The production and constant reproduction of the image of Jesús Malverde are attributed to the first chaplain of the place, who sought the artist Sergio Flores to make a representation of the image of the generous bandit with features similar, supposedly, to those of the face of film characters that would have represented the Mexican of that region during the era of Cine de Oro (Lizárraga, 1998; Lazcano and Córdova, 2002; Fabián, 2016).

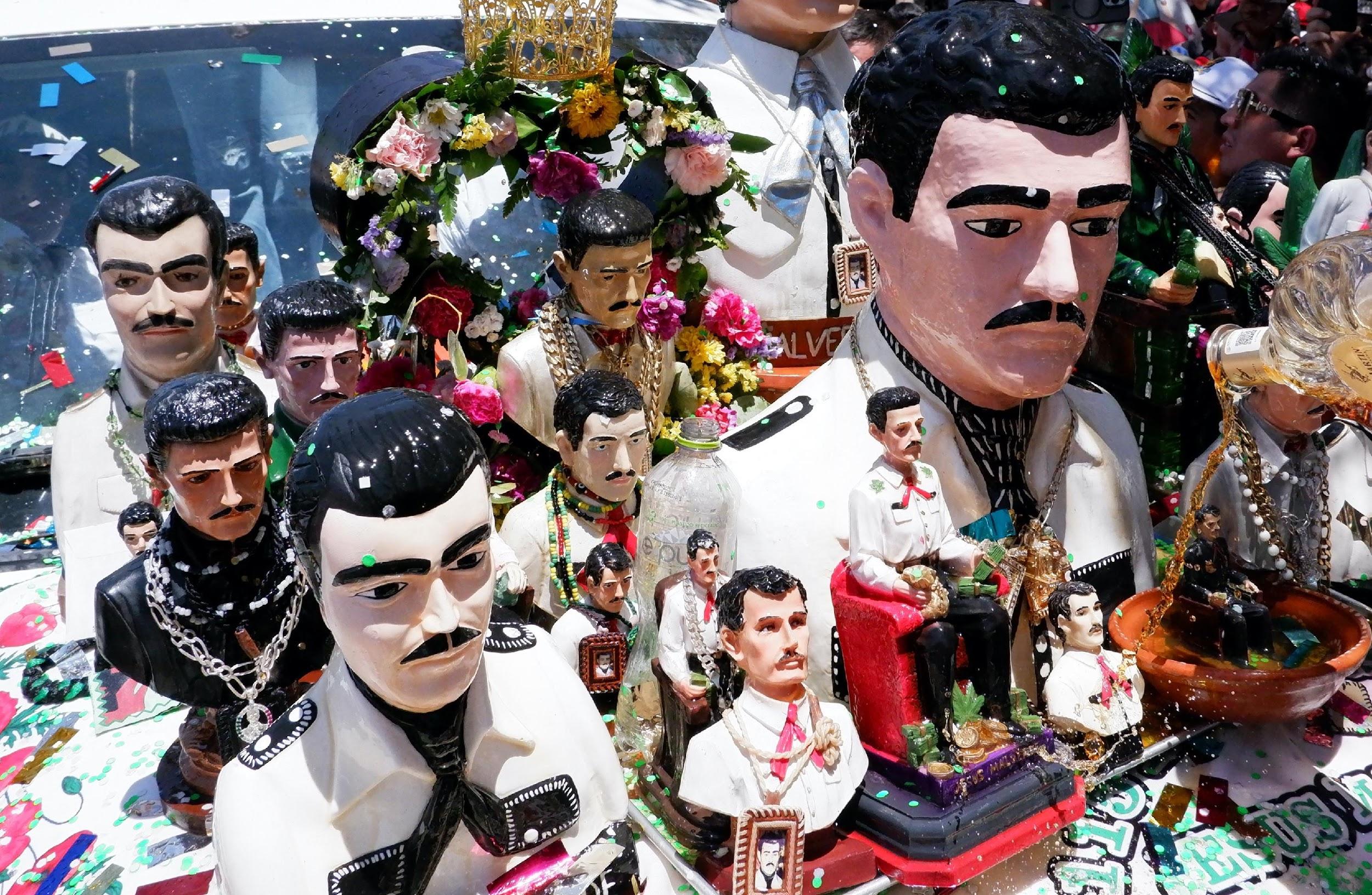

The production began with the bust of Malverde, but over time figures of his full body, of him sitting on a throne surrounded by dollars and marijuana leaves, have been marketed. Although some figures have certain alterations that distinguish them from the original, all are similar to the one in the central part of the chapel in Culiacán. The introduction of a material representation of the saint that would allow us to know the features and physical characteristics of the character, as well as the objects that surround him, once again manages to transfigure the hitherto wandering soul of the generous bandit into a "flesh and blood" character. This introduces the notion of the saint of drug trafficking, although he had already been one, only in a more discreet way; but this time not only his acts as a bandit, but his image and his actions as an anima synergize with the figure of the Mexican capos. Narcocorridos would play an important role in the propagation of the cultural representation around the patron saint of those who had to circumvent the authority during drug trafficking to the United States (Gudrún-Jónsdóttir, 2006; Flores and González, 2011).

This small religious organization (Fabián, 2016; 2019), since the beginning of the chapel, has been in charge of the arrangement of votive offerings and candles deposited by the faithful inside the place, either as an offering, as thanks or as a petition to intercede for them. In the place you can find braids of hair, clothes of an infant, photographs, religious images of both the Catholic faith and other popular saints (Cortés and Mancillas, 2007). Some walls are covered with votive offerings and bills of different dollar denominations with petitions or thanks written on them. The organization is in charge of finding a place inside the chapel and arranging and removing the objects that have served their purpose.

The profits and alms have been used to pay the commissions of each member of the organization or to buy items such as wheelchairs, crutches, and boxes for the dead that are often requested, not so much by the devotees, but by neighbors of the area and migrants. More recently, at the beginning of the millennium, both in the celebration of the anniversary of Malverde's death on May 3, and in the "posada" held a few days before Christmas, raffles of gifts are held for the families and children who attend these events; in the chapel, household appliances, construction materials and toys are handed out.

During the first decades of the 20th century xxiThe presence of Jesus Malverde in Mexican pop culture and in different cultural and artistic manifestations at a global level, mainly integrated into kitsch art, has been remarkable. The icon, which represents the bust of the generous bandit or the saint of drug trafficking, transcended different sacralized and profane forms to become a product or the image of products such as beer bottles (Cortés and Mancillas, 2007). With this, his face is desacralized as a benefactor of certain sectors of Sinaloa society to be reformed as a global cultural product.

While it is true that during the last century xx both the theatrical representation of Rider of Divine ProvidenceThe narco-series and documentaries on the life of drug traffickers, including that of Malverde himself, are also elements that have been integrated in more recent years to the ways in which the character has been represented in the arts and audiovisual media.

Finally, although Jesús Malverde could never have the legitimacy of the saints of the Catholic Church, he does have social recognition and legal legitimacy (Fabián, 2019) as the saint of a popular cult and benefactor of different sectors of Mexican society. In recent years, his legitimacy and official recognition is no longer the concern of the malverdista organization, nor is it the concern of his devotees. Towards the end of the pandemic caused by covid-19, the synergy between the Malverdista cult with the Yoruba religion and Santeria began to be visible, establishing its legitimacy hand in hand with these other saints.

In light of digital advances, we can point out that since the 1920s the presence of the Yoruba religion and Santeria within criminal groups involved in drug trafficking has become increasingly notable; first in Mexico City and, shortly thereafter, in other locations, the presence of necklaces dedicated to Elegguá in the social networks of "narcoinfluencers" in the northwest of the country was notorious. Narcocorrido singers have also begun to make the cult's presence noticeable in their verses.

This reaffirms the relationship between Malverde with characters such as Santa Muerte of the seven powers and other more discrete elements of these Afro-Caribbean belief systems, although it is important to clarify that these elements are borrowed, as have been other core teachings of the Catholic tradition. Just as we see Yemaya re-signified as Santa Muerte, it is Malverde who feeds on Elegguá's properties and is re-signified within the Yoruba pantheon as a representation of the road-opener in a crossroads of belief systems (De la Torre, 2001; 2013).

How the phenomenon has been studied

Jesus Malverde as a social phenomenon has been studied from different points of view ranging from the symbolic, historical, organizational, literary, as well as socioeconomic aspects related to his adherents. There is also interest in its relationship with other saints and other belief systems outside the official ones. In particular, studies related to Malverde have to do with the dichotomy between good, represented by the generous bandit, and evil, represented by the saint of drug trafficking. The truth is that this character could not be so emblematic if it were not for the identity and history of the place where he was born: Culiacán.

Culiacán has been described as a narcotized city (Oliver, 2012), in which different governing forces converge, including organized crime resulting from drug trafficking. The chapel in honor of Malverde is one of its main supports. From a certain point of view, its history goes hand in hand with the history of drug smuggling in Sinaloa and its capital city.

The "black legend" in Sinaloa (Córdova, 2011), as this historical episode that began in the sierra during the 1930s and "concluded" with the implementation of Operation Condor, almost 50 years later, is usually called, is the period in which the production, trafficking and sale of opium gum emerged and consolidated itself as one of the most lucrative businesses in the state's countryside (Lazcano and Córdova, 2002). The business began as a local business between peasants and businessmen who cultivated "black rubber" that they exported out of the state, in an alleged complicity with the government, mainly to meet the needs of the consumer population in the United States. All of this was intended to counteract the crisis and poverty in the Sinaloa countryside (Lazcano and Córdova, 2002; Cortés and Mancillas, 2007).

The 1940s were critical, as Sinaloa experienced economic contrasts that resulted in increased migration and drug trafficking. This new social context helped connect that part of Malverde's life addressed in his myth with the difficult lives of those who migrated or who became involved in drug trafficking (Perea, 2020). The drug trafficking business in Sinaloa makes Culiacán not only the state capital, but the capital of drug trafficking in Mexico, precisely because this is one of the most profitable businesses in the criminal world. Its consolidation is evidenced by the emergence of narcoliterature, narcoculture (Córdova, 2011) and the proliferation of cult spaces such as the chapel dedicated to Malverde, that is, a narcotized city (Oliver, 2012).

Along with the chapel, there are other sacred spaces where values such as economic and luxurious wealth are exalted as a synonym of success. This can be seen in one of its main cemeteries, Jardines del Humaya, whose exclusivity resides in the luxurious mausoleums and the importance of the characters buried there. Bravery and heroism adhere to the stories and legends about the exploits of these characters and, at the same time, to the local identity.

Some of these representations, rather than characterizations of the cruelty of crime in contexts of drug trafficking, can become moralizing banners in criminal battles such as the one currently taking place in that city (Oliver, 2012: 96). With the violent events that began in September 2024, tombs and other sites sacred to drug traffickers involved in the war between both factions of the Sinaloa Cartel have been destroyed, making it clear that the moralization or demoralization of the opposing sides in a narcotized city is possible through the destruction of its most representative sacred symbols.

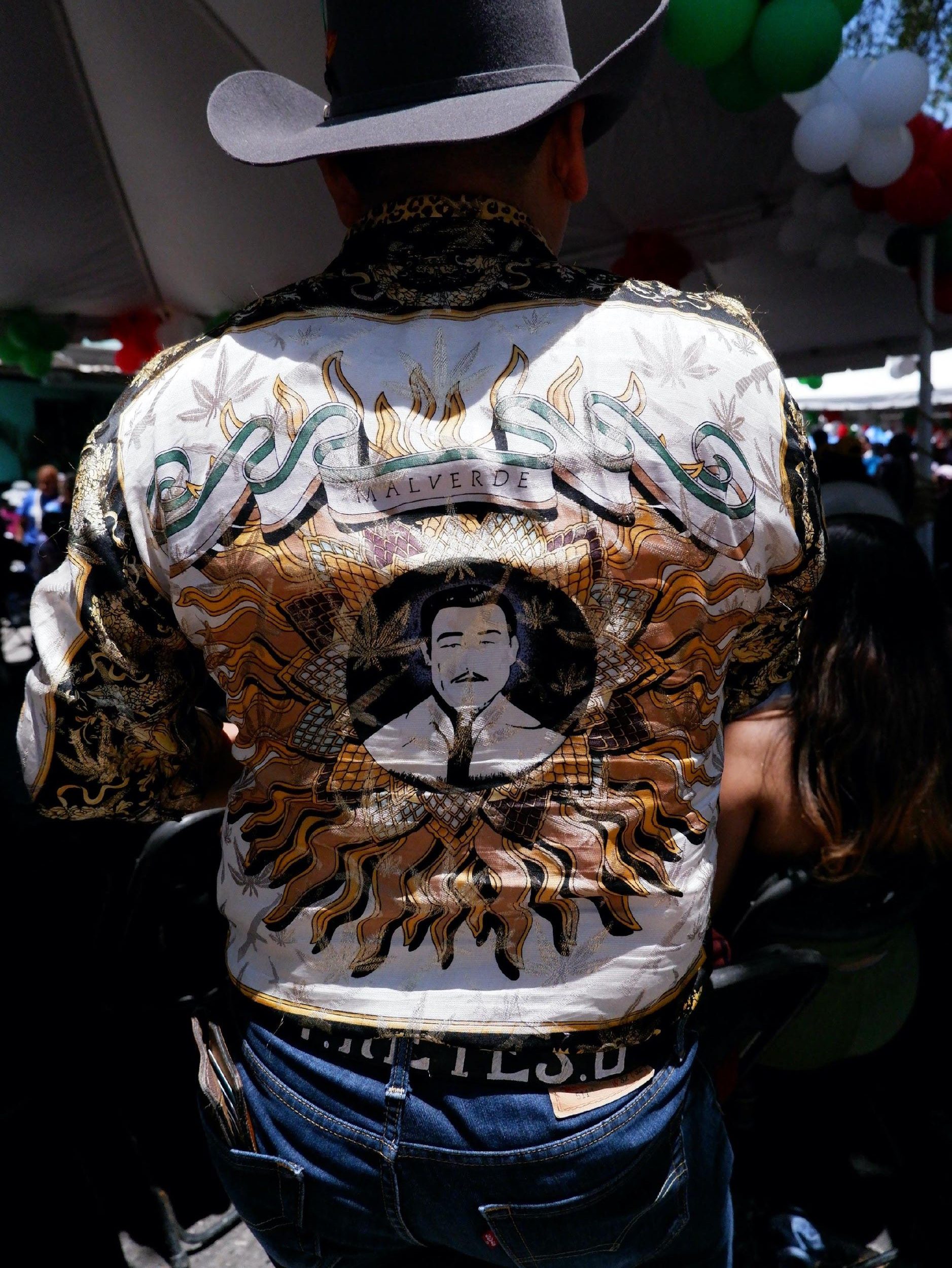

Culiacán also tends to be a place of fashion. On the one hand, the contributions of the Culiacán valley to the world of fashion have come from the ranchero style characteristic of musicians and singers such as Chalino Sánchez or Los Tigres del Norte, a style that has been said (in the voice of Los Tucanes de Tijuana) to have replaced the fashion of the pachucos in the region and is present in the image of Malverde created at the beginning of the eighties of the last century. However, the transition of Mexican society from the countryside to the city, which characterized the second half of the 20th century, was a major factor in the development of this new image of Malverde. xxAlthough the ranchero or cowboy style is still present, it is the Italian brands and designer clothing that are among the interests, not only of the big capos, but of everyone who is part of the narcoculture (Córdova, 2011; Oliver, 2012).

With respect to literature and other artistic manifestations, the presence of narcoculture is almost a hallmark of what is made in Culiacán. The myriad of narcocorridos written by an army of composers not only offers impressive amounts of material for analysis and discussion about the music itself, but about the exploits, confrontations and loss of life of some of the region's native criminals (Ramírez-Pimienta, 2020). In more recent years, contemporary art has also printed pieces with the same stamp, such as exhibitions made with the very blankets of the people murdered and found wrapped in blankets in vacant lots.

Playwrights and novelists have also been inspired by the figure of Malverde. The work of Oscar Liera, Rider of Divine Providence -released in 1984-explores the conflict between the Catholic Church and Malverde's followers in Culiacán. The novel by Leónides Alfaro, The curse of Malverdetells two stories linked by the geographical and cultural context of Sinaloa, interweaving the legend of Malverde with more contemporary narratives. Also discussed is Eduardo Galeano, the Uruguayan writer, who wrote about Malverde depicted as a Robin Hood figure. Arturo Pérez-Reverte's novel, Queen of the Southincludes a description of Malverde's chapel. Élmer Mendoza has made very precise descriptions of the environment in which the saint is surrounded in his writings (Cortés and Mancillas, 2007).

Social Bandit

From the academic point of view, one of the first works that is illustrative of all that surrounds Jesús Malverde and that can still be found in some libraries is the essay titled Malverde, a generous bandit (López-Sánchez, 1996), which contains relevant and less diffuse information than other more current sayings about the foundational myth. Likewise, in this text, the author uses a description to refer to the chapel, which he calls a hermitage.

In his description, Sergio López-Sánchez explores a place still in "humble" conditions, with very rudimentary architecture both inside and out. However, he mentions that other saints from the Catholic pantheon are already present, including images of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Jesus Christ. He also reports that the sale of spiritual products and services is located on the outside of the store. López-Sánchez (1996) also narrates the most recent events, related to the removal of Malverde's cross from its original place and the permanence of the tomb for some time until it finally disappeared from the public space.

Arturo Lizárraga's (1998) ethnographic observations, on the other hand, help him understand how the cult of Jesús Malverde is the product of a "selective tradition. That is to say, traditions and symbols from both the past and the present have been deposited in it, combining official saints and local heroes that give meaning to the reality in which people live. In this way, the researcher explores in the experiences of the people interviewed what they know about Jesús Malverde. Thus, the "angel of the poor" (Lizárraga, 1998) becomes a necessary category to understand that Jesus Malverde is considered until that time as a hero who sought among his causes to guarantee the welfare of poor people.

Lizárraga not only explains the foundational myth, but also questions it by opposing the story of Jesús Malverde with that of Heraclio Bernal. Likewise, the researcher affirms that, indeed, Jesús Juárez Mazo was born in Las Juntas, Mocorito, on December 24, 1870; the narrative around Malverde is selectively constructed with the passage of time in which the constant, in the voice of his interviewees, is that "he always helped the poor".

Arturo Fabián (2016) studies the historical context and social conditions that allowed the emergence of the myth and religious identity of Jesús Malverde. He highlights the unequal economic policies, social injustices and the corrupt political system of the Porfiriato in Sinaloa, which helped construct Malverde as a "social bandit" (Cázares, 2008) and who later became an important figure in the narcoculture. The author emphasizes that understanding this historical context is essential to understand the importance of Malverde and his contemporary veneration, in addition to the constant reinterpretation of his meaning that allows his persistence (Fabián, 2016).

On the other hand, there are researchers who suggest that the presence of figures such as Malverde or Santa Muerte are indicators of stressful socioeconomic realities in certain regions of the country, as well as the human attempt to control these situations of uncertainty (Dahlin, 2011). That is to say, these devotions are a manifestation of the anguish much more present in the less privileged and unprotected sectors. In particular, the corridos dedicated to Malverde, until a few years ago, stood out for being analogies of legends of banditry and the Mexican Revolution reworked by drug traffickers (Gudrún-Jónsdóttir, 2006; Flores and González, 2011). These analogies -accompanied by norteño or banda music- have been introduced not only in the taste of the public interested in that musical genre, but have also contributed to the continuity of the dichotomy between the sacred and the profane in which these two ideas of a generous bandit and a drug trafficking saint are sustained in the same character (Gudrún-Jónsdóttir, 2006).

Malverde from a postmodern perspective

Different researchers have observed the phenomenon from a postmodern point of view in which Malverde is located among fortune tellers and tarot readers, astrologers and practitioners of alternative medicine (Hidalgo-Solís, 2007); the media and the nascent social networks, rather than churches or temples, have operated as showcases that exhibit these characters as alternative magical-religious solutions to the problems of everyday life. Qualities such as being a northern Robin Hood, combined with those of the social bandit, aim to reduce the problems of a public tired of injustice and inequality, which to some extent allows the articulation of a phenomenology of Malverde fed by a certain need to believe in a better future in the face of overwhelming modernity (Hidalgo-Solís, 2007).

They are belief systems and religious and spiritual practices that operate as a support in the face of reality, which should be understood as the manifestation of a malaise caused by modernity (Hidalgo-Solís, 2007; Oliver, 2012), rather than an indicator of poverty and marginalization among the adherents of this and other cults. These symptoms of social malaise -attended in a magical-religious way by saints such as Malverde or Santa Muerte-, for the postmodern position are a possible explanation for the increasingly prolonged abandonment of the faithful to Catholic doctrine (Degetau, 2009) in the face of new offers in the Mexican religious market.

Within this framework, we develop the vision of approaching Malverde as a "popular subject" (Park, 2007; Gómez-Michel, 2009); we start from the study of the discursive forms inscribed in the work of Óscar Liera, Rider of Divine Providencewhich concentrates the discourses found during two different periods in the life of the generous bandit: one that has to do with his work during his lifetime as a bandit and the other, after his death, as an embodied imaginary that provokes fear accompanied by terror and violence in the metabolism of power represented by drug trafficking, a kind of popularly sacralized anti-hero (Park, 2007; Gómez-Michel, 2009).

Malverdist iconography

Some works on the iconography of the Malverdist iconography have been generated from the production of religious articles and photographs, such as the study dedicated to the photographic supplement of the book "The Malverdist Iconography". Malverde. Exvotos y corridos by Enrique Flores and Raúl Eduardo González, to analyze the images of the Malverde cult as a form of visual testimony (Riobó, 2022). Here a semiotic-hermeneutic approach is used to study these photographs, arguing that they provide information about the historical cycles of the cult, the identity of its believers and their association with criminal activities.

The analysis reveals that the photographs not only document the diversity of the cult, but also challenge the role of the researcher as passive observer, emphasizing that the images capture the fluidity and diversification of the cult, as well as the cultural hybridizations that shape it. Ultimately, the article underscores the value of documentary photography in capturing the complexity and evolution of popular religious expressions, as well as the importance of analyzing them from a non-colonialist perspective.

Regarding the votive offerings dedicated to Malverde, it is known that those located in the chapel serve as a testimony of the faith and gratitude of the devotees for the miracles (Perea, 2020). These offerings represent a moral pact between the believer and the saint. They are key to understanding this phenomenon, as they are visual representations of the miracles granted by Malverde. Their study reveals different representations of Malverde, as they often incorporate images of marijuana leaves, dollars and guns, and other symbols that reflect the lives and concerns of the devotees. The most frequent themes in the exvotos are related to family, health and work. The diversity of ex-voto types: large format paintings, written messages, photographs, and metal plaques, among others, attest to the different socioeconomic backgrounds of those who venerate Malverde. They also demonstrate the persistence of the imaginary of the social bandit, which provides a sense of hope and refuge for those experiencing injustice and uncertainty (Perea, 2020).

Conflict with authorities

Some scholars see the cult as a result of religious syncretism, especially among marginalized groups, highlighting the tensions between the established Church and the needs of subaltern populations. For example, Ida Rodríguez (2003) considers worship as a rupture between the ecclesiastical institution and the needs of the subaltern, while Jorge Degetau (2009), from an anthropological perspective, interprets sanctification as a syncretic product sustained by marginalized groups.

Malverde represents an important figure in the struggle to take a place in the sacred space of Culiacán (Price, 2005). A struggle that reflects conflicts that go beyond a simple landscape and manifests itself as a tension between the official and vernacular landscapes, the latter understood as the marginalized who are not part of the former but seek a place of their own. In that sense, within the chapel, Malverde constitutes an empty signifier, which produces an infinity of meanings fed by different narratives around the character (2005).

A significant part of the literature associates the cult with the expansion of drug trafficking in northern Mexico, considering it a symbolic product of narcoculture related to the expansion of power among drug traffickers (Sánchez, 2009); it is also argued that the cult is inseparable from drug trafficking, which has shaped its symbols and rituals (Cantarell, 2002). Anajilda Mondaca (2014) sees Malverde as a symbol of power rather than popular religiosity, linked to narco aesthetics and used by illegal armed groups. Likewise, although the role of narco-trafficking is recognized, she also highlights the presence of other believers from subaltern groups (Fernández-Velásquez, 2010).

On the other hand, some studies link Malverde to undocumented migration and symbols of identity among Mexicans living outside the country. His figure is represented as a national symbol for immigrants, providing protection and a sense of regional identity (Arias and Durand, 2009). However, the association of Malverde with crime, by referring to a narcocult belonging to the Mexican narcoculture, has not been entirely well received in the United States (Zebert, 2016), since immigration authorities find it as an element of proof to ensure that the owner of the cult objects is someone related to drug trafficking, in order to be detained, prosecuted and, in some cases, even deported.

Kristín Gudrún-Jónsdóttir (2006; 2014) uses the concept of subalternity to analyze the cult as a belief system outside the official Church, highlighting the importance of music, the mixture of the sacred and the profane, as well as the role of rituals. To do so, he delves into literary works that have taken the figure of Malverde as a fictional theme, such as the aforementioned play Rider of Divine Providence and the novel Jesus Malverde. The popular saint of Sinaloa by Manuel Esquivel (2015).

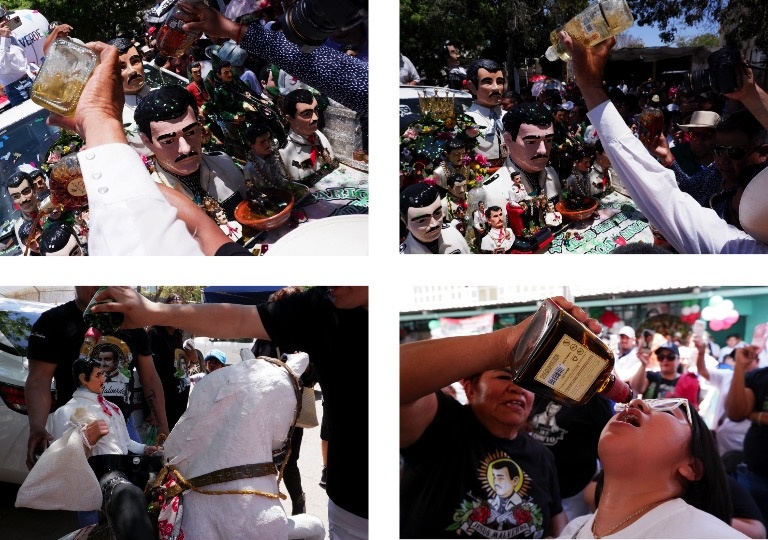

Regarding the devotees and religious tourism that circulate during his mourning anniversary, it has been found that the phenomenon is mainly motivated by religious reasons that attract local, national and international visitors who coexist among symbols of narcoculture, which also links the site with dark tourism (Guzman and Flores, 2023). The events observed by Sandra Guzmán and Silvestre Flores (2023) included musical performances, alcohol consumption, and the sale of souvenirs with images of Malverde. They also mention that visitors came from various places, including other states in Mexico and the United States. The ritual included bathing the statue of Malverde in alcohol. The pilgrimage to honor the saint is a significant element of the visit, while the connection to narcoculture represents the darker side of the site. The site serves as a space for personal devotion and has links to the criminal world (Guzman and Flores, 2023).

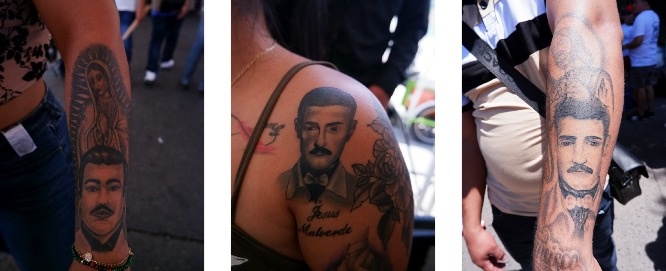

Cults dedicated to Santa Muerte, Jesús Malverde and the Angelito Negro offer their followers forms of identity, protection and survival in contexts marked by violence and marginalization (Gaytán and Valtierra, 2023). Here tattoos are a crucial element in the identity and commitment of Santa Muerte devotees. These visible marks seal the pact with the deity and reinforce community membership. Although perceived as a stigma by outsiders, tattoos are symbols of protection and fidelity. In contrast, Felipe Gaytán and Jorge Valtierra (2023) state that the followers of Jesús Malverde do not resort to tattoos, but rather use objects such as medals or necklaces. Devotees of the Angelito Negro practice self-laceration as a sacrifice and connection to the supernatural. These divergent practices show the variety of ways in which cults symbolically manage the fear and uncertainty generated by violence.

As shown in this section, the religious phenomenon of Malverde has been approached from different perspectives, emphasizing the diversity of elements that frame and contextualize him as the anima of a generous bandit and as the saint of drug trafficking. The foundational myth that originates with the tragic death of Jesús Malverde has been widely discussed. Similarly, there is evident interest in characterizing his devotees, belief systems and religious practices that have derived from the cult of the anima. The study of music and literature has not only been sustained, but is continuously fed by new cultural products such as narcoseries and "tumbadas" evocations.

In particular, the study of the material and symbolic framed in votive offerings, tattoos, clothing and clothing accessories, ritual objects, etc., is the subject of this photographic essay, as it is intended to contribute to the development of the inventory of these salvation goods that are produced both by the Malverdista family and by the devotees themselves. In this sense, an update is offered both of the literature generated during the last five years, as well as an update of "salvation goods" observed during the visit to the chapel in 2024.

Methodology

Production and consumption of popular salvation goods

As mentioned, the raw material of this essay is the salvation goods generated around the cult of Jesus Malverde. That is why talking about the Mexican religious market implies recognizing the great diversity of denominations that daily generate marketing strategies to attract Mexican believers to their churches. It is worth remembering that with the reform made to the Mexican Constitution and its respective laws, at the beginning of the nineties of the last century, Mexico became a liberal country, even in terms of recognizing freedom of worship and no longer being a monopolistically Catholic and Guadeloupean country. With this, different churches are legally recognized and regulated by the State, guaranteeing the freedom of Mexicans to choose among different denominations the one that best suits their spiritual needs and faith.

The sociological theory of religion on religious economies (Finke, 1988; Frigerio, 1995) points out that in a modern society, in which religious freedom is guaranteed by law and legitimized by the State, an economic supply-demand relationship can develop between the different churches and society. This approach is limited to seeing, from an economic point of view, churches as producers of salvation goods, according to the needs of the social groups that make up the religious market (Stark and Finke, 2003; Finke, 2004). In this way, it is understood that historically some North American churches have been competing with others to establish a producer-consumer relationship with society, through the salvation goods market in the United States (Finke, 1992).

Regarding popular religiosity (De la Torre, 2016), it is necessary to point out that, most of the time, it is not supported by an ecclesial institution or any church, but by forms of social and community organization within which the structure of a certain church is usually subordinated. This situation makes the economic approach complex, since consumers in popular religiosity also tend to contribute to the production of salvation goods; the forms of organization tend to be of a more emergent type (Fabián, 2019); and legitimacy is usually granted by society rather than institutions such as the state. However, these belief systems are going to be fueled by certain "nuclear teachings" (Finke, 2004), especially Catholic ones.

Both the inherited traditions, mainly from Guadalupan Catholicism, as well as the innovations produced within the sociocultural frameworks of northwestern Mexico, shape this type of religious and moral nuclear teachings around Jesus Malverde and his cult (Fabián, 2016; 2019). In this way, it is not difficult to understand that in a religious celebration, such as a patronal feast, the social and the religious converge within the frameworks of the sacred and the profane.

As noted, in its consolidation stage, a small form of organization was formed in the cult of Malverde, which to this day continues to administer both the chapel and the salvation goods. The "Malverdist family", as they usually call themselves, is the "institution" that produces and offers (and at the same time consumes) the Malverdist salvation goods (supply-side) that can mostly be observed during the religious celebration or patronal feast that takes place every May 3 in the chapel of Culiacán (Fabián, 2019).

Participant observation and cognitive tools

With the theoretical-conceptual basis presented, we sought to deepen in the circulation of salvation goods related to the cult of Malverde. Now, the presence or absence of these goods, as well as the increase or decrease in their production, defines the current state of the cult; for this reason, it is necessary to elaborate records of these goods in order to know their processes of transformation, change, etc. The "anthropological gaze", typical of Mexican anthropology, contains an impressive range of methods, tools and techniques for the collection and analysis of information obtained in religious festivities, carnivals, patron saint festivals, funerary rituals, etc., and is a pillar of this essay.

The ethnographic work of participant observation allows the incorporation of audiovisual tools to assist in the recording of what was observed in the field. Thus, the use of photography is very useful when collecting information for later analysis. However, it is necessary to understand that the anthropological gaze in general and participant observation in particular do not refer only to the use of a set of ethnographic methods for collecting information in the field, but to the use of oneself as a "primary" tool to understand social realities, behaviors and meanings within their own contexts.

We start from visual ethnography as a method, since it implies the use of photography to study social configurations and to obtain a critical distance from the ethnographic activity in the religious field, because it allows to materialize the visible forms of worship in a certain spatio-temporal context (Chatagny, 2021). Both the collection and the processing of visual data must consider the reasons behind the position and the point of view of the researcher when the photograph was taken. Thus, photographic data are a construct of the researcher and must be part of an analytical framework; the knowledge stored in the photograph is specific and makes visible those elements of a situation that were already there, but were not noticed during the field visit (2021). Thus, observing does not only imply looking through the photographic lens: it is necessary to understand that observation is found from the natural order as an inherent human ability to perceive the world using the senses since we are born. In this order, observing implies experimenting and discovering the environment driven by curiosity, without the need for specific tools or training (Quintana, 2021).

In contrast, scientific observation is a systematic, intentional and planned process used to understand phenomena, among which social phenomena are located. It is a key component of the scientific method, requiring a clear objective, careful planning, and structured data collection (Quintana, 2021). Tools and instruments support and record observations, while data are analyzed and interpreted to draw conclusions. Participant observation is a fundamental technique in qualitative research, especially in ethnography, in which the researcher is integrated into the group under study to understand its dynamics holistically. To facilitate this process, researchers develop and employ various tools that allow them to collect and analyze the information gathered in the field more effectively.

Participant observation - like all scientific observation - must be clear about the purpose of the researcher's intervention, and therefore must be supported by the researcher's objectives. This process will facilitate the identification and selection of specific behaviors during the field stay. The design of tools typical of qualitative studies, such as checklists or rating scales, is fundamental to assist in data collection (Quintana, 2021). However, when doing photographic participant observation, a researcher must consider several tools and cognitive skills (Andrango et al2020) because they enhance the ability to collect meaningful data and interpret social phenomena accurately, and have the potential to improve the visual observation skills needed for participant observation.

1) Visual cognitive tools: during photographic participant observation, visual tools such as mind maps and concept maps can help researchers organize initial thoughts and understanding of the environment being photographed. These tools can evolve as the observation progresses by visually depicting connections between different aspects of the study, such as relationships between individuals, recurring themes, spatial configurations, or key events, thus facilitating subject selection, shot composition, and identification of significant visual elements within the frame. Creating sketches and diagrams of the environment can enhance understanding of spatial relationships and inform photographic choices.

In this sense, in the case of the phenomenon observed in this work, the previous visits to the chapel and the constant return to previous editions of the anniversary and the posada allow a preview of the development of routes, movements and rests that take place during the celebration of the feast. This facilitates the ability to structure and order the spaces occupied by both adherents and religious images throughout the festivity.

2) Cognitive organizational tools (graphic organizers): graphic organizers or techniques for studying the visual grammar of the image can be used to establish visual relationships in order to structure field notes more easily, linking them to specific photographs and identifying key concepts, relationships and sequences of events captured in the images. Similarly, timelines help to trace the chronology of the events photographed, while cause and effect diagrams serve to analyze the factors contributing to the religious phenomenon documented in the images. Categorization systems are useful for classifying photos according to themes, subjects, or compositional techniques. These systems can be created by paying attention to the interactions between people, their actions and beliefs, as well as their own questions and regulations.

3) Cognitive tools of inference: problem-solving situations can be used (srp) to analyze complex interactions or unexpected events encountered while taking photographs. They are tools that activate and focus thinking for the expansion and contraction of ideas, their organization, decision making, the clarification of arguments and the development of creativity (Andrango et al., 2020). In this way, researchers can explore different interpretations of photographs, consider alternative viewpoints, and make informed decisions about which images to capture and how to frame them.

For the present work, the development of these cognitive tools has allowed the elaboration of the photographic section of this essay. The photographic production process depended on them, which contributed to improve the composition of the photographs, to define the series of photographs by means of the categorization systems and to solve problems based on creativity. It is important to emphasize that it is not only the action of documenting what is observed, but the action of recording and communicating what is observed at the same time.

To use the gaze or the photographic eye, as it is colloquially called, to use the camera and generate communicative records is to use these tools throughout a process of visual production, ranging from the preparation of the camera settings and the type of lens to be used, to the lighting conditions at the moment of taking a photograph. In this sense, the development of the photographic eye corresponds to the development of cognitive skills related to the human eye itself and the respective cognitive and mental processes that allow us to press the shutter release button.

This perspective recognizes that the researcher's observations are filtered through individual experiences, beliefs, and knowledge. This type of cognitive observation also recognizes that personal history, emotions and biases influence what is observed and how it is interpreted. Individuals can only see and observe what they have constructed "within" themselves (Andrango et al2020); therefore, observers should be aware of their biases and how they might affect their perceptions.

With the above we want to emphasize that participant observation is not only an auxiliary tool of qualitative research, in which the residues of the interviews and what is observed with the naked eye are deposited. On the contrary, it is by means of this technique supported by tools and techniques of photography and cognitive tools of the human being that the observations made in the field are based, as far as this photographic essay is concerned, in order to contribute to the study and inventory of the assets of salvation of the embezzlers.

Having said the above, the following section is fed by the results obtained during the fieldwork, mainly on the anniversaries of Jesús Malverde's death. A substantial part of their analysis is presented here, while the other part is found in the photographic essay from which this document is derived. In this sense, the references to the photographs found in this section correspond to the study of the images within the photographic section of this work.

The assets of embezzler salvation

The patronal feast of Jesus Malverde is the ideal scenario to carry out a constant review of the salvation goods present in the Malverdist beliefs and practices. The traditions and innovations contained in the Malverdist nuclear teachings are exposed and put into practice during the celebration of May 3 each year. This essay highlights what was observed during the 2024 celebration.

It should be noted that I have constantly visited the chapel since 2015, with the exception of the years of confinement caused by the covid-19 pandemic. For this essay, various categories or types of goods such as the replicas of the image, especially the bust of Malverde, were tracked. We also observed the bearers of these images who accompany Malverde during his procession. Tattoos are an element that is beginning to take shape as a tradition, since it is normal to see during the festivity, especially during the procession, that people take off their shirts to show their tattoo of Malverde.

Traditions of the Malverdist faith

Some of the traditions associated with the cult of Malverde, such as the feast itself, which is a good that has already been described on different occasions, are Catholic customs or core teachings that come from the Catholic faith and are reproduced and re-signified within the cult of Malverde. To this day this fact continues to be represented as a manifestation of the Malverde culture. During the celebration, stones continue to be carried to the main altar of the chapel, in some of which one can read the petition and the command to which they are committed. However, this practice is increasingly in disuse, and now it is the candles and votive offerings that arrive in large quantities, to fulfill the same purpose, although in a slightly more profitable Christian way.

Over time the face of Malverde has had several changes as an object of worship. Let's remember that in the early years the anima, ghost or spirit, that is, an inanimate figure, was Malverde and the material was his tomb of stones and his cross of railroad beams, which were animated, palpable and observable objects. As it is known, the bust of this saint is the current representation; for about four decades it was characterized by an artist and it is considered the original image of Malverde.

The cross of Malverde (see image 1) that is heard mentioned in praises and corridos is still present at the entrance of the niche where the original bust of the generous bandit rests. In that niche as well as in those on the sides of the chapel there are several handmade replicas of the character, some surrounded by figures of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Jesus Christ, St. Jude Thaddeus and Santa Muerte, mainly (see image 3). The association of this figure with the other Catholic saints in charge of caring for and protecting their devotees is a legitimizing tradition of Catholic spirituality, since it can be seen that he is a member of the pantheon of devotion of people who seek to deposit a candle in the niche.

Consecrating the images of Malverde by pouring liquor over their heads (see images 11 to 14) is a practice that has remained a tradition during the procession, at first exclusive to the members of the chapel, but today it is carried out collectively. This action and others involving intoxicating beverages or psychoactives are generated from syncretic representations taken from other traditions to Catholicism. In Malverde's feast, in addition to spilling drinks on the saint, liquor bottles are shared among devotees in order to get drunk and, to a lesser extent, there are those who consume cannabis near the main image during the procession.

In relation to the cargueros, it was possible to observe a representation of approximately one meter in size of the figure of the generous bandit riding his horse (see image 4), which in turn is on a metallic structure that allows it to be carried on the shoulders. Other cargueros, during this date, take out from their personal or family chapels their own images of Malverde and carry them to accompany the image in the main niche during the procession, either riding their image on the same truck or walking in procession beside it (see image 10).

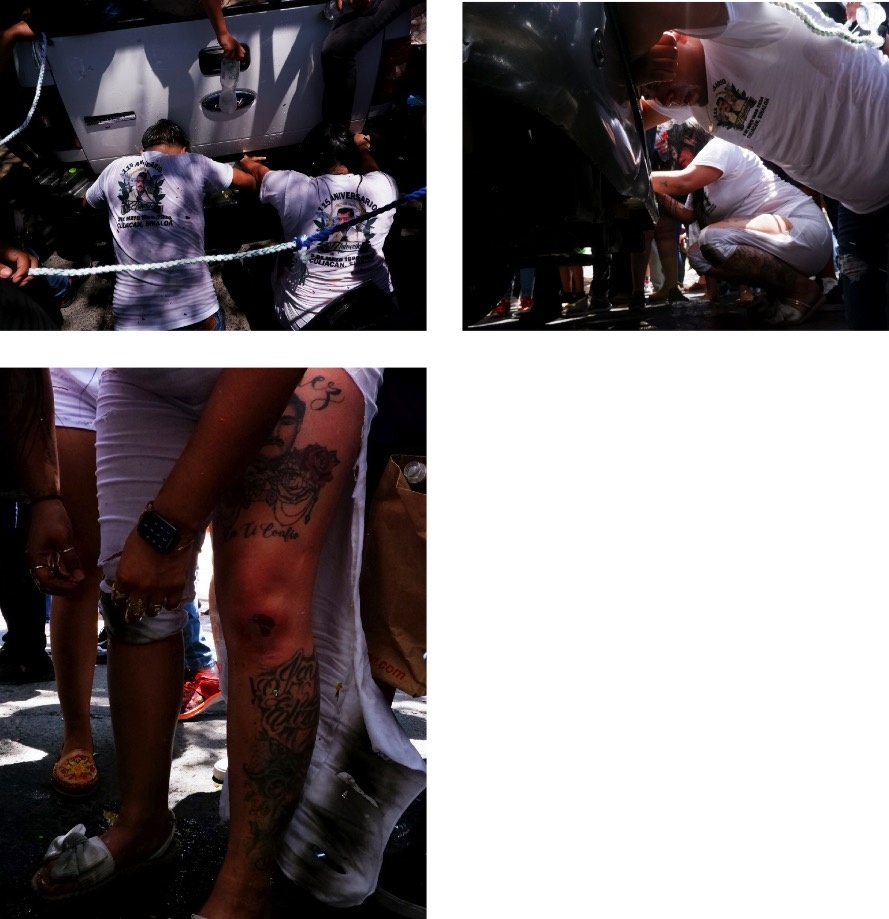

A tradition that has been observed since the visit made in 2015 and remains constant during the procession is related to the exhibition of tattoos of Malverde's face. It is natural to see devotees who during the procession expose the tattoos on their backs, chest, shoulders, among other parts of the body (see images 6 to 10). In 2024 the presence of the generous bandit on forearms, hands or legs was notable and novel, besides being more and more stylized and accompanied by other Catholic saints (see image 6).

The "buchón" style of dress is part of the characterization of some adherents. Both those in charge of the chapel and other devotees and merchants have tried to keep the image of Malverde present, both in clothing and clothing accessories (see image 5). Band music is another element that manifests itself during the procession. It is known that Malverde likes corridos, which is why some of them glorify the characters pointed out as the "patron saint", whose actions of banditry have been similar to those of his saint. Other musical genres have been performed in previous years; however, after the pandemic and the violent events that have occurred in recent years in the city, the absence of different actors is notorious.

Innovations

During the 2024 visit, I was able to document two people who decided to do penance by walking on their knees behind the main image during the tour (see images 15 to 17). This was an unusual occurrence, as it requires special care due to the intense heat of Culiacán. Nevertheless, this tradition that can be observed more frequently in guadalupanismo than in malverdismo has similar resonance from a common base which is popular Catholicism. "Walking" on one's knees is considered a popular act of faith that involves genuflection and penance, two Catholic spiritual practices, taken to the extreme.

The level of complexity of performing this penance increases when factors such as the extreme heat of the tropics, the burning concrete in the middle of the day and the lack of experience of the penitents to carry out spiritual practices of this type are added to the fact of walking on their knees; however, it is an innovative practice within malverdismo, since previously the penitents were the ones who had to comply with the command to visibly wear a body tattoo of the saint.

For several years, jewelry, scapulars and other religious paraphernalia have been the elements that decorate the front of the truck that leads the procession, which is sacralized by bathing it with whiskey or tequila; however, a recent innovation has to do with the increasing presence of the Yoruba religion within the frameworks of the "narcoculture". Malverde has not been the exception and the material presence of elements such as necklaces or representations and interventions on the image of the saint such as painting his clothes in seven colors/powers is evident in the fiesta (see images 18 to 21).

Finally, I wish to highlight two elements that I consider relevant. The first has to do with the tolerance and respect towards this type of popular cults by society. Unlike a few years ago when being a malverdista was punishable by North American laws (Zebert, 2016) and criminalized by both authorities and Mexican society, this change is reflected in different cultural representations within the fiesta, but the practice of getting tattoos as a manda or penance stands out in particular. In recent observations, I could notice that the devotees no longer perform their tattoos in hidden parts of their bodies, as many of them tattoo the image on their arm or forearm, and wear better elaborated and more decorated designs (see images 6 to 8).

The other aspect that stands out comes from the category of gender. The presence of female devotees is notable, as well as the production of salvation goods destined to this sector. While it is true that the figure of Malverde has been described as masculine, emulating the image of characters that stood out for their "Mexican macho" appearance, it is also true that throughout these years it has gone through different interventions made by both devotees and merchants. In recent observations, I noticed that the image has begun to stand out with false eyelashes, blue eyes, blush on the cheekbones and lipstick (see image 21).

A cargo vessel was also observed with its version of the amigurumi of Malverde (see image 22), which intertwines fashions and trends from different global popular cultures with Mexican popular religiosity. The same goes for the tradition of getting tattoos to pay mandas. In these last observations, not only are more and more women (see images 6, 7, 14 and 17) wearing tattoos of the saint's face, but they also have them on visible parts of their bodies. It is important to make this point about the female category not because of their greater or lesser participation in the feast in comparison with before and after or with the number of men who attend, but because of the salvation goods that are introduced by them and for them in relation to the Malverdist faith, so I consider it relevant to follow up on this issue.

Final thoughts

Knowing how popular cults are kept in force, as well as the practices and beliefs that are generated within them is a necessary task to understand the Mexican religious field or market. In this photographic essay we sought to know the dynamics of popular salvation goods, both in terms of traditions and innovations, which are present during the celebration of the festival of Jesus Malverde in Culiacán, in order to understand how the supply of popular salvation goods remains dynamic between the traditional and the innovative, and thus its cult remains in force.

In this search, it was possible to document different salvation goods, certain innovative practices and some others coming from both the Catholic tradition and other belief systems. With respect to the latter, traditions, at least those present during the festivity, are increasingly framed within an environment of tolerance and respect for the environment. In this sense, keeping within the order and norms established by popular Catholicism is a preponderant factor in the development of practices that have remained constant in recent years, such as getting tattoos as a commandment. In other words, Catholicism as a popular base contributes to the social and regulatory legitimacy of certain salvation goods.

The procession, during the celebration of May 3, remains as the main religious practice that generates popular salvation goods; there is a concentration of images from personal and family altars, as well as their carriers that join the procession. Within this tradition, innovations were found in different figures carried by the cargueros. Particularly noteworthy are the innovations related to the Yoruba religion, such as hanging Elegguá necklaces on the saint or painting his clothing in the colors of the seven powers or deities of the Yoruba pantheon. In this sense, the more and more constant use of false eyelashes in the eyes of some figures of the saint or blush on his cheeks also stands out.

Traditions such as the spiritual practice of getting tattoos as manda have not only remained in force, but have developed as a socially acceptable practice among men and women devoted to Malverde. Within this tradition there are also innovative elements both in terms of designs and in the parts of the body where they are done, mainly in places that are increasingly visible and tolerable to the sight of other people, even without the fear of being arrested by the authorities for the simple fact of having a tattoo of Malverde.

It is necessary to remember that in popular religiosity the production of salvation goods and their consumption do not depend only on religious institutions, but on the participants themselves, which includes women within malverdismo. This occurs not from their attributes within the narcoculture, but through the production-consumption of popular salvation goods manifested in some of the photographs in this essay. Today it is clear that their role is at a superficial level to be observed as a category of analysis, so it will be necessary to deepen in the spiritual needs of people that encourage the creation of this type of goods, among other sources of information, through future analysis of the malverdista system of production of salvation goods.

Bibliography

Andrango-Toaquiza, María Fernanda; Lourdes Carmen Guanoluisa-Toapanta, Aída Marina Cañar-Chasi y Edwin Orlando Muso Lema (2020). “La implementación de herramientas cognitivas en la educación general básica y educación básica superior”, Ciencias de la Educación, vol. 6, núm. 4, pp. 1267-1278. http://dx.doi.org/10.23857/dc.v6i4.1535

Arias, Patricia y Jorge Durand (2009). “Migraciones y devociones transfronterizas”, Revista Migración y Desarrollo, núm. 12, pp. 5-26. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S1870-75992009000100001&script=sci_abstract

Cantarell, Melvin (2002). Malverde y Bernal, el santo y el héroe en la historia de la violencia, criminalidad y narcotráfico en el noroeste de México. Culiacán: Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

Chatagny, Guillaume (2021). Experiencing a Mosque through Photography: Islam as an Ordinary Religion, Visual Ethnography, vol. 10, núm. 2, pp. 31-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.12835/ve2019.1-0161

Cortés Aguilar, Stephanie y Yollolxochitl Mancillas López (2007). “Religiosidad popular. Canonización popular y culto a Jesús Malverde en Culiacán, Sinaloa”. Tesis de licenciatura. México: Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Cázares, Pedro (2008). “Bandolerismo y politización en la serranía de Sinaloa y Durango, 1879-1888”. Tesis de maestría. Culiacán: Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

Córdova, Nery. (2011). La narcocultura: simbología de la transgresión, el poder y la muerte; Sinaloa y la “leyenda negra”. Culiacán: Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

Dahlin-Morfoot, Miranda (2011). “Socio-Economic Indicators and Patron Saints of the Underrepresented: An Analysis of Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde in Mexico”, Journal of the Manitoba Anthropology Students ́ Association, núm. 29, pp. 1-7.

Degetau, Jorge (2009). “Malverde y la Santísima: cultos y credos en el México posmoderno”, Metapolítica, núm. 67, pp. 20-24.

De la Torre, Renée (2001). “Religiosidades populares como anclajes locales de los imaginarios globales”, Metapolítica, núm. 5, pp. 98-117. https://www.academia.edu/57209765/Religiosidad_popular_Anclajes_locales_de_los_imaginarios_globales

— (2013). “La religiosidad popular”, Punto Urbe, núm. 12, pp. 2-20. https://doi.org/10.4000/pontourbe.581

— (2016). “Ultra-baroque Catholicism: Multiplied Images and Decentered Religious Symbols”, Social Compass, vol. 63, núm. 2, pp. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0037768616629299

Fabián, J. Arturo (2016). “Preservación y renovación de festividades en la religiosidad popular: La familia malverdista”. Tesis de maestría. Culiacán: Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

— (2019). “Organizaciones religiosas emergentes: la familia malverdista”, Ra Ximhai. Sinaloa: Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México, vol. 14, núm. 1, pp. 41-61. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6906390

Fernández-Velásquez, Juan Antonio (2010). “Breve historia social del narcotráfico en Sinaloa”, Revista Digital Universitaria, vol. 11, núm 8, pp. 1-13. https://www.revista.unam.mx/vol.11/num8/art82/art 82.pdf

Finke, Roger (1988). “Religious Economies and Sacred Canopies: Religious Mobilization in American Cities”, American Sociological Review, vol. 5, núm. 2, pp. 41-49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095731

— (1992). The Churching of America, 1776–1990: Winners and Losers in our Religious Economy. Londres: Rutgers University Press.

— (2004). “Innovative Returns to Tradition: Using Core Teachings as the Foundation for Innovative Accommodation”, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 43, núm. 1, pp. 19-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2004.00215.x

Flores, Enrique y Raúl González (2011). Malverde. Exvotos y corridos. México: unam.

Frigerio, Alejandro (1995). “‘Secularización’ y nuevos movimientos religiosos”, Lecturas Sociales y Económicas, vol. 2, núm. 7, pp. 43-48.

Gaytán Alcalá, Felipe y Jorge Valtierra Zamudio (2023). “Acto icónico de los ángeles marginales. Cultos religiosos y violencia en México en perspectiva comparada: Santa Muerte, Angelito Negro y Jesús Malverde”, en Ángel A. Gutiérrez Portillo (ed.). Pesquisas sobre religión: Pensamientos, reflexiones y conceptos. Villahermosa: Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco.

Gómez-Michel, Gerardo (2009). “Jesús Malverde: un santo maldito en los límites de la modernidad”, Webzine Translatina, núm. 8, pp. 133-139. https://www.academia.edu/898949/Jes%C3%BAs_Malverde_un_santo_maldito_en_los_l%C3%ADmites_de_la_modernidad

Gudrún-Jónsdóttir, Kristín (2006). “De bandolero a ejemplo moral: los corridos sobre Jesús Malverde, el santo amante de la música”, Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, vol. 25, núm. 25, pp. 25-48.

— (2014). Bandoleros santificados: las devociones a Jesús Malverde y Pancho Villa. San Luis Potosí: El Colegio de San Luis.

Guzmán, Sandra Zulema y Silvestre Flores (2023). “Visita a la capilla de Jesús Malverde: entre lo oscuro, lo religioso y lo turístico”, Dimensiones Turísticas, núm. 7. https://doi.org/10.47557/PZOH1175

Hidalgo-Solís, Marcela (2007). “Aproximaciones desde la (post)modernidad a la fenomenología de Malverde, el santo de los traficantes”, Humanitas, vol. 4, núm. 4, pp. 19-37. https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/HumanitasRevistadeinvestigacion/2007/vol4/no4/2.pdf

Lazcano Ochoa, Manuel y Nery Córdova (2002). Una vida en la vida sinaloense. Los Mochis: Universidad Autónoma de Occidente.

Lizárraga, Arturo (1998). “Jesús Malverde: el ángel de los pobres”, Arenas, núm. 1. Culiacán: Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

López Sánchez, Sergio (1996). “Malverde, un bandido generoso”, Fronteras, vol. 1, núm. 2, pp. 32-40.

Mondaca, Anajilda (2014). “Narrativa de la narcocultura: estética y consumo”, Revista Ciencia desde Occidente, vol. 1, núm. 2, pp. 29-38. https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/CienciadesdeelOccidente/2014/vol1/no2/4.pdf

Óliver, Felipe (2012). “Sobre Malverde, el narcocorrido y la ‘ciudad narcotizada’”, Isla Flotante, vol. iv, núm. 4, pp. 89-97. https://bibliotecadigital.academia.cl/server/api/core/bitstreams/c2e5b6d7-58c9-48cb-979c-a4b29ed93a5a/content

Park, Jungwon (2007). “Sujeto popular entre el bien y el mal: imágenes dialécticas de Jesús Malverde”, Revista de Crítica Literaria y de Cultura. Pittsburg: Universidad de Pittsburg, núm. 17. https://www.lehman.edu/media/Ciberletras/documents/ISSUE-17.pdf

Perea, Diana (2020). “Jesús Malverde: el imaginario colectivo del bandido social y los exvotos en su capilla, 1909-2019”, Revista Escripta, vol. 2, núm. 4, pp. 42-68. https://revistas.uas.edu.mx/index.php/Escripta/article/view/197

Price, Patricia (2005). “Of Bandits and Saints: Jesus Malverde and the Struggle for Place in Sinaloa, Mexico”, Cultural Geographies, vol. 12, núm. 2, pp. 175-197. https://hal.archives- ouvertes.fr/hal-00572149/document

Quintana Yañez, Katherine (2021). La observación, una herramienta clave en la práctica de psicomotricidad educativa (Cuaderno de Psicomotricidad Educativa, núm. 2). Santiago: Ministerio de Educación de Chile.

Ramírez-Pimienta, Juan Carlos (2020). “‘El bazucazo’: un antecedente histórico de la guerra contra el narco en la corridística mexicana”, Cultura y Droga, vol. 25, núm. 29, pp. 163-181. https://doi.org/10.17151/culdr.2020.25.29.8

Riobó Rodríguez, Juan Camilo (2022). “Apuntes para el estudio de la santificación popular desde la fotografía documental: el culto a Jesús Malverde en México”, Ponta de Lança: Revista Eletrônica de História, Memória & Cultura, vol. 16, núm. 31, pp. 75-97. https://ufs.emnuvens.com.br/pontadelanca/article/view/18655

Rodríguez, Ida (2003). El culto a Jesús Malverde. Todo tiene su tiempo para ser creído incluso las mayores falacias. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, unam, pp. 1-28. https://www.esteticas.unam.mx/edartedal/PDF/Bahia/complets/RodriguezMalverde.pdf

Sánchez, Jorge (2009). “Procesos de institucionalización de la narcocultura en Sinaloa”, Frontera Norte, vol. 21, núm. 41, pp. 77-103. https://doi.org/10.17428/rfn.v21i41.977

Stark, Rodney y Roger Finke (2003). “The Dynamics of Religious Economies”, en Michele Dillon (ed.). Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 96-109. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/handbook-of-the-sociology-of-religion/dynamics-of-religious-economies/B154F640CFF7DEA94CED3DE108A85C11

Zebert-Judd, Megan A. (2016). “Material Representation: Narco Religiosity in New American Conception”. Tesis de maestría. San Diego: San Diego State University. https://digitalcollections.sdsu.edu/do/2ae01080-edc2-425b-9fe5-35a5f73c0778

Arturo Fabian Jimenez is a researcher and documentary filmmaker with extensive experience in the study of religious phenomena and popular religiosity in Mexico, as well as in the analysis of migration and violence against migrants in regions such as the Darien. She is a specialist in the analysis of unofficial cults and the production of salvation goods, with a particular focus on the figure of Jesus Malverde. Her work combines ethnographic and photographic methods to document and analyze the practices and beliefs of diverse religious communities. In addition, she has researched and documented the plight of migrants through video documentary production to capture their experiences and make visible the violations of their human rights. She has presented her research at national and international conferences and has published several articles in specialized journals, providing a more comprehensive and accessible view of religious and migratory dynamics in contemporary contexts.