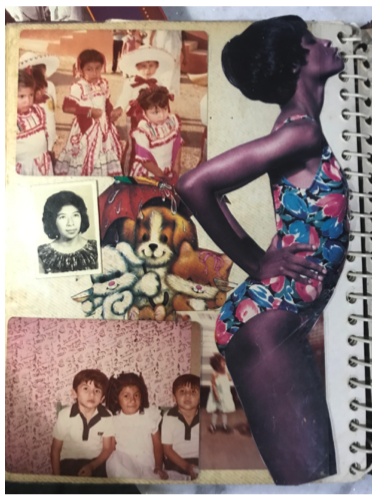

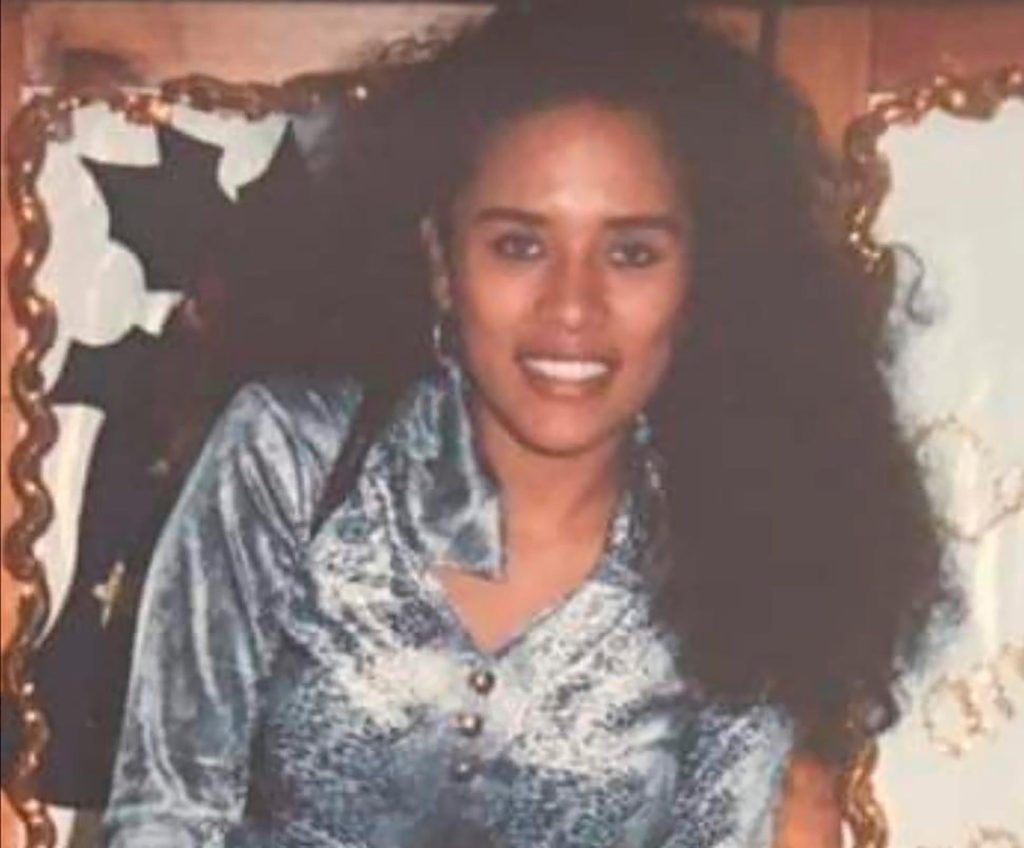

My grandmother's face

On the left, Rosma shows me a snapshot of a photo of her paternal grandmother during a visit to her mother's house to see the family album. On the right a close-up of the photo, which is a clipping of a photograph that is part of a memory of a family visit to Mexico City in the 1980s. His grandmother was the daughter of a fisherman born in Loma Bonita, Oaxaca, who had lived in Veracruz since he was a child.

It's the only photo I have of my paternal grandmother. That's where I got the hair and the brown [...].

Dialogues with Rosma

Ambivalences

With hipil de gala (terno or Yucatecan regional costume) reserved for special and festive occasions. This costume, considered "traditional" in Yucatán, was created from the dress used by the Yucatecan mestiza (indigenous woman) to dance jarana in the state's famous vaquerías; over time, it became a hallmark of Yucatecan identity (Repetto and Medina, 2020: 243).

My mother "[...] was in political groups, I don't know exactly what she was doing, but López Portillo was going to arrive, there was going to be a welcoming committee for the president with women and they were given their suits. They lent it to them. My mom never wore mestiza dress, no woman in my family. My mother and grandmother spoke Mayan, but they denied it. There was that contradiction, because they did not wear the traditional costume, but they did have several daily practices related to the Mayan, the use of domestic space, food, daily utensils, following important dates of the agricultural calendar [...] I built over time respect and love for the link with the Mayan that was denied me by the family lineage."

Dialogues with Rosma

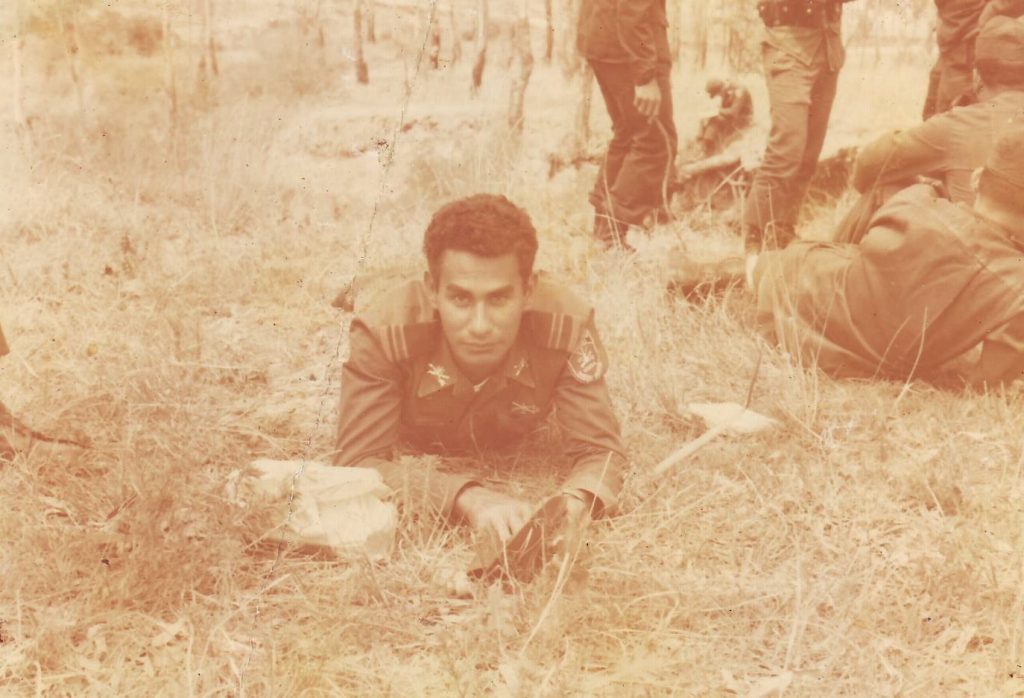

José Garduza, the father

This is a photo of the field practices [...i.e.] the soldiers' field practices that they carried out every so often to train in the field and learn how to survive in uncomfortable conditions. This must have been in Rio Lagartos or San Felipe, that's where they went for their training. My dad became a soldier when he was 22 or 23 years old and was part of Battalion 33 in Valladolid, where he met my mom.

Memories of Rosma

[...] all my life I saw my dad who is very dark and his hair is very curly, like that, pashushitoThere was a "hey, his hair is different, the color of his skin is very dark, isn't it? But it's not only that he had that, but he had other features different from the Yucatecan, like maybe his height, maybe his figure, there were other features in him that I saw [...].

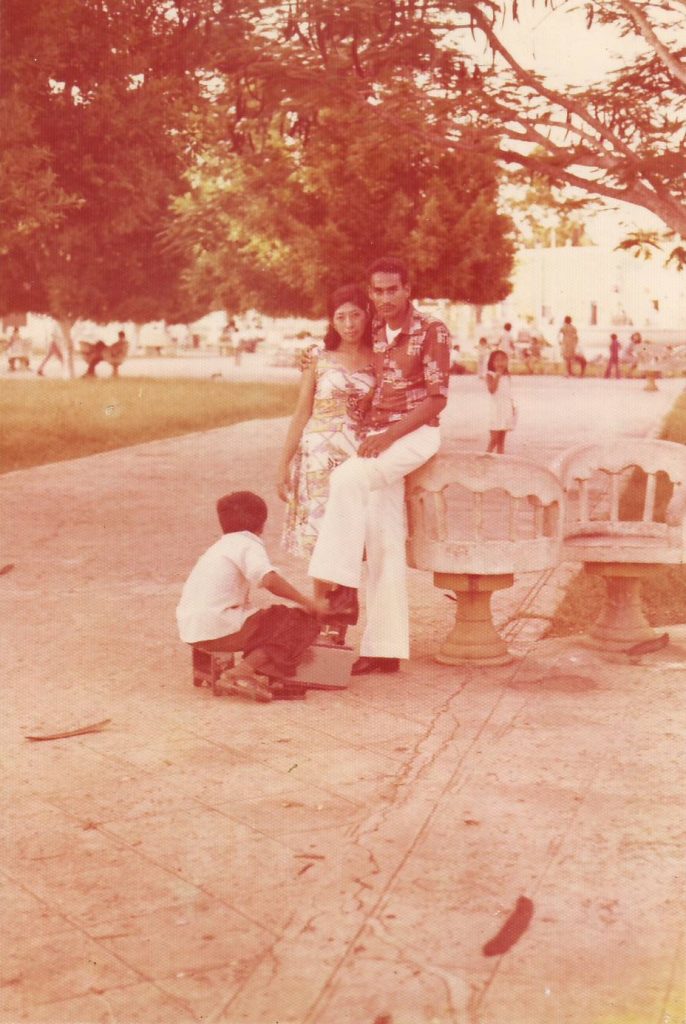

In civil

I like this photo of my dad because it is one of the few where he is not a soldier [...] but he is from the army because his rifle is over there [...] I think it is San Felipe [Yucatán coast], because it is an old house that looks like the house of an aunt who lived there [...] he is very young...how handsome he was...my mom liked his legs [...] My dad was outstanding in sports, he always represented the army, he traveled a lot. He was a man who liked to prepare himself [...] when he met my mom he didn't know how to read or write and he enrolled in the same elementary school where I studied, he went in the afternoons; and he learned to read and write, that was before I was born [...] I know he had a very hard life, I have no idea why [...].

Memories of Rosma

Dating

Here she is with Don José in the park. I think they were just beginning to be sweethearts. They were about 23 or 24 years old [...] My mom doesn't have a naïve face, but a naughty face," she says with a laugh, "bandit! I can say that my mom grew up in the culture of whitening. In fact, she told me that her parents said to her, 'Are you crazy, your kids are going to be born brown with that man! It was almost as if they were saying she'd had a backflip [laughs again]. And yet she chose a black man [...] and she loved that her children were brown and curly-haired.

Memories of Rosma

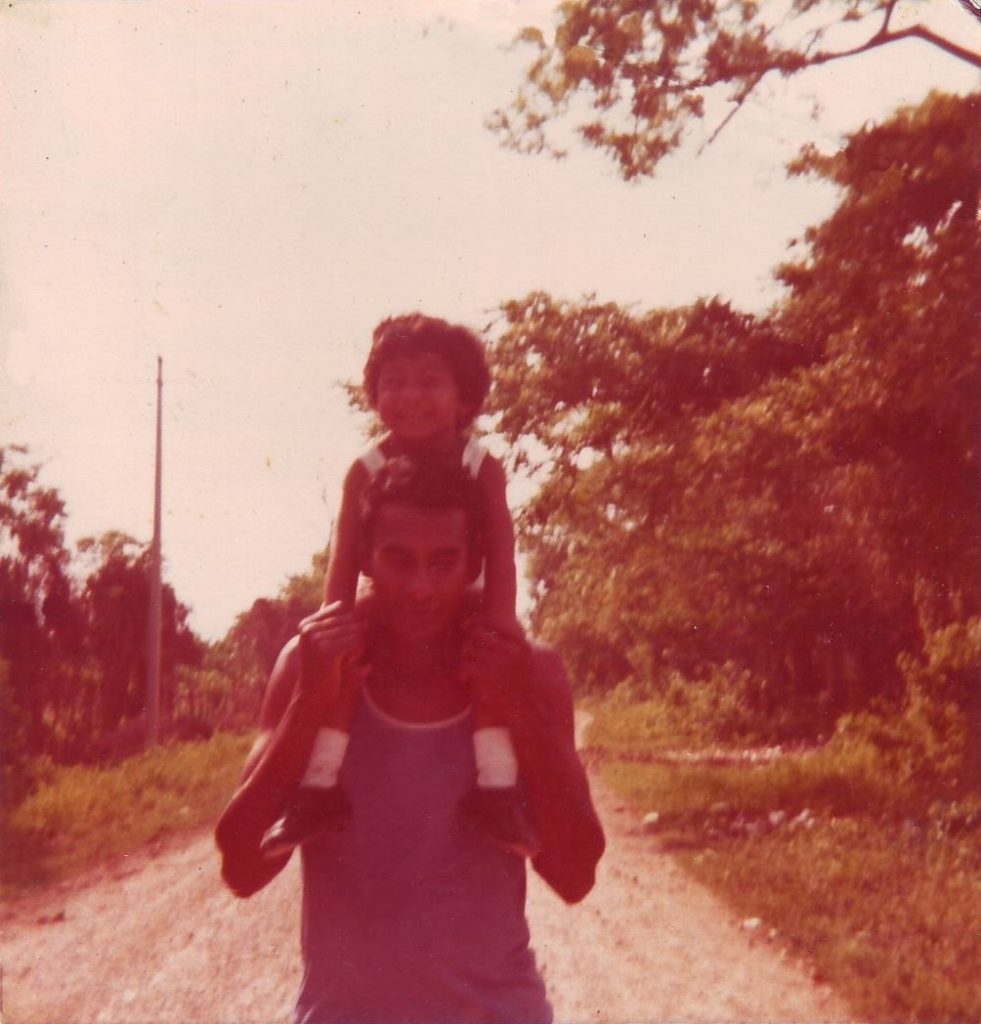

Absences and marks

This photo provokes two emotions in me. On the one hand, nostalgia for a love that didn't happen, that was broken. But at the same time, I think: 'It's part of the past, it doesn't have to belong to the now'. He was a good dad, playful [...] that kind of dad. The rest, to tell you the truth, I don't remember much. He was often away for the army. I don't know at what point was the transition to not seeing him anymore [...] I just stopped seeing him.

Memories and reflections with Rosma

I was three years old in that picture. And although I don't have many memories of him, the ones I do have are very nice.

Sometimes I think: 'How strong, isn't it? And it also pisses me off that I have been so absent [...] and that at the same time he has left me all the legacies that are noticeable.

Maternal family

Family album photo. Merida, Yucatan. Around 1990

In the center, Rosma's maternal grandmother. On the right, her mother, Rosma and her brother. On the left, her aunt with a granddaughter in her arms, one of her daughters and her brother's daughter.

This was in the house that an uncle lent my mom, before we moved to the one she got through Infonavit [...] I was 14 years old. We were clearly brown compared to my cousins, who were white. It's a nice photo, you can see the popular environment in which I grew up [...] My mom always called me 'Negrita'; that was my nickname, and my brother she called him 'Negrito'. We were always black. The thing is that at that time I didn't link it with an idea of Afro-descent. And now it's like [...] well, obviously there is a relationship, but it's not that I feel represented within an Afro culture.

Memories and dialogues with Rosma

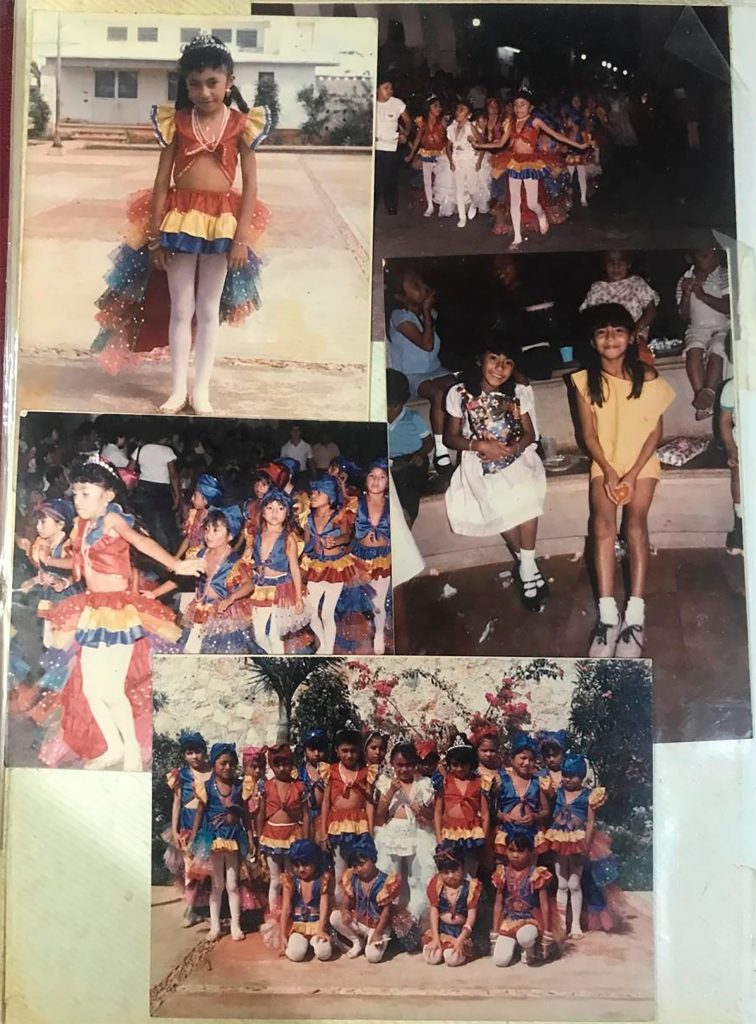

The dress and the fine tailoring

The dress represents a network of support woven through sewing, a practice that provided sustenance and social mobility to Rosma and her family. The craft of dressmaking, as well as the care and dedication in its execution, were an inheritance from her mother's lineage: from her mother, a professional seamstress, to herself, a jewelry maker.

Here I was 11 years old. This dress was made for me by my mother. She had been sewing professionally since she was 13 years old in a workshop with her cousins. I remember I was very fond of that dress [...] I loved the headdress, it was incredible, really, exquisite. She used very fine lace because my mother had already started working with a designer from New York who gave it to her.

Memories of Rosma

My first communion godmother was a woman who was very supportive of my mother. She was a lady with a high economic position, her boss at Cadenita Gold, a maquiladora where my mother worked. She knew how to see that my mother was delicate, meticulous [...] There is an aesthetic that I inherited from her. My mother never did anything shoddy, she liked exquisiteness. She had a deep respect for her craft. She was brutally committed to her work. She enjoyed it.

My grandmother, from a young age, warped hammocks. Her husband, my grandfather, was a blacksmith.

Memories of Rosma

The area

This was one of the most beautiful times of my childhood: the time of the [military] zone. Those were the houses where we lived, a very nice and safe subdivision. We had a ballet teacher there -she was the one who gave me the crown- [photo above left].

Memories of Rosma

All these girls you see here [lower photo and upper right photo] were from different places: Guadalajara, Oaxaca, Mexico City [...] we shared life in the colony. In these photos we are dressed as rumberas, it was carnival time. Lupita, who was the queen, was from Oaxaca. There were several girls from there; their mothers were big, big women [...] Juchitecas. I remember them very well.

Zoom

It's my cousin's wedding. We are my mother, my brother [...] I think even my cousins, but I cut out the photo to keep only my image, to look at myself. It's part of this process of rediscovering myself. Here I look very black, although my hair is straight. I love this photo because of the color of my skin, which stands out a lot. I was about nine years old.

Memories of Rosma

You know what fascinates me? The color my mom let me wear: roooojoo. I love it because I look like a little devil with my little horns," she laughs. My grandmother said it wasn't a suitable color to wear. From her Catholic point of view, it had a certain logic [...].

The beauty

Naomi Campbell (right) was not originally in the album. It was stuck on the wall in my room. When I vacated it, I tore down all the posters [...] but this one I didn't want to throw away. I cut it out and decided to keep it there. Obviously it was because of her beauty and the color of her skin. I was about 14 or 15 years old.

Dialogues with Rosma

In the photo below I am with my cousins. They always called me 'Sorulla', I was always the black girl in the family [...].

When I was 14 I had a friend named Lupita. She used to tell me: 'No, look, you're beautiful, look! She would fix my hair in a way that I didn't do, with mousseThe curl was very tight to mark the curl. For her it was very cool that I was brown. She did see in me an Afro-descendant trait that I, at the time, could not recognize. Maybe that's when I started to see myself differently [...] You know what I mean?

The game of mirrors

I was 14 years old [...] I think it was then that I began to feel deeply how my personality was configured. It was because of a cousin-in-law, the partner of a cousin, that I met at that time. She began to shape much of my identity. She was from Mexico City, brunette, brunette, brunette. I kept a picture of her because, imagine, to me she was beautiful. I proudly showed her off saying she was my sister, not my cousin.

Dialogues with Rosma

I liked her personality, how she dressed. She always wore her hair very curly, afro. It made a big impact on me. Besides, she talked to me about things that no one had ever talked to me about: sex, drugs, the wildness, chupe [...] I liked her hair so much that one day she took me to get my spirals done. She paid for them. It's strange, because I didn't have curly hair, but in that photo I do: I have spirals, and I felt a little more represented. I love that kind of hair [...].

Framing

I cropped this photo because I like that angle. I like it a lot: the composition, my hair, my face. We had these pictures taken in the workshop. I like my expression lines, because that's where you can see my forties. That you can see a jewel, the light, the color of the clothes [...].

Dialogues with Rosma

I do have an ideal of a woman: to know how to be a strong, upright woman, with poise. I realized, when I grew up, who is considered "dark" and who is not, depending on the context. I was delighted to discover these nuances.

Ball nose

This is one of my favorite pictures. I love our little ball noses. Sometimes I tell my son: -Hey, my love, we are black, aren't we? [referring also to his father, a dark man] And he, very correctly, answers me: "No, mom, we are not black, we are brown.

Dialogues with Rosma

The other day, in La Plancha,* I saw a girl of African descent and I said to him: -Look, what a beautiful color she has. And he answered me: -Mmm, I don't like it. I like the color of millionaires better. And I said: -And what is that color [laughs]? -More white, he said. And I: -Well [...] it's not of millionaires, there are poor and rich people of all colors. But it did make me think: where do these ideas come from?

*La Plancha Park. Public recreational space in Merida, Yucatan.

The patina

Seventeen years ago I had the opportunity to develop my manual skills and aesthetic sensibility in the Restoration Department of INAH. It was an incredible experience to touch, feel and connect with objects that had had their splendor centuries ago. I was fascinated to observe the details of the Mayan vessels, to imagine the workshops where they were made, the pigments they used [...] and how those colors remained alive even after centuries of burial. The apartment was full of pre-Columbian and colonial objects. Since then, I have had a fascination with patina: the clear and forceful trace of time left on things.

Dialogues with Rosma

"Beauty in the simple and crude."

I love this photo because of my hair: always loose, unruly and abundant. My jewelry has a deliberately raw, crude, powerful aesthetic.

Dialogues with Rosma

I once made a moodboard with images of women who inspire me. They were all African or Indian, tribal women, in their daily life [...] They have such a dignified look, so full. I hate those poses of models where they look like fragile, careless girls, with their legs bent [laughter] [...] hyper-sexualized, always complacent.

Profile, selfi

I took this picture myself. I loved the light in that house. I was in my work corner, noticed the halo of light falling on me, closed my eyes and took the picture. I love my profile there.

Dialogues with Rosma

The subject of the Mayan profile is not one that I have always celebrated. It was through other looks that I recognized it. Foreigners celebrate it a lot. Once I was told that my profile looked like the glasses in a museum. And yes, I looked at it and I thought, 'Sure, it's a Mayan profile!'

But there are also Spaniards and Moroccans with aquiline noses [...] they see you with their own imaginary. Now nobody asks me if I'm from India, but when I was thinner, they always asked me. Or if I was from Bangladesh. And now, if I'm a black woman [laughs].

Jewelry maker

[...] I am trying to capture in words this strength, this presence, this transgression of what is imposed on you as conventional jewelry [...] When I work I connect with my emotions, there is a lot of connection with what I do, I like to work in silence, in my corner, it is an island, surrounded by books, and jewelry, plants, and I am in my world.

Dialogues with Rosma

[...] it is difficult to put a description to this photo, but I feel a mystique [...] looking at my work in a tone of respect. Wearing my jewelry with a Calder book [...]

Many brown people like me, at some point I talked to girls, entrepreneurs too, and many of them have thought that the success of my jewelry is due to the foreign look they think I have. How strong, right? their imaginary [...] because they also feel talented, but they feel that they have not stood out like me because they do not have this flattering phenotype [...].

Image 21. Afro roots

"Let no one doubt my Afro roots [...] [ironic tone] Phenotypically I can believe that I have Afro elements and Mayan elements, but not cultural identity [...] phenotypically yes, I see it in the mirror and I recognize it.

Reflections with Rosma on identity

[...] in the end I am not [Afro-Mexican, Afro-descendant, Mayan], because I do have traits but those same emotions I have with the Mayan, eh? At some point I also identify myself closer to the Mayan, but I don't feel legitimate either, you know what I mean? At some point I said: 'It's just that they are quarts of my identities that are there, right? Why can't we reconcile all those parts?' I feel them [...] like this [...] fluctuating, around, right? But not completely part of me.

Do you know what really marks me as an identity? The popular culture, the knowledge that I come from a popular environment, from low-income backgrounds, that is, well, like maaaaaaaaaaa, a class identity that I have stronger".

Bibliography

Fernández Repetto, Francisco and Ana Teresa Medina-Várguez (2020). "Dressing Yucatecan identity. Etnomercancía, tradición y modernidad", Entrediversidades. Magazine of Science Social and Humanities(19), pp. 241-275.

Gutiérrez Miranda, M. (2023). "First approaches to the concept of image. selfie as a sign of self-representation and self-concept", in Ángeles Aguilar San Román and Pamela Jiménez Draguicevic (eds. Processes cross-cutting of the expression, the representation and the significance. Querétaro: Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, pp. 103-129.

Nahayeilli B. Juarez Huet is a research professor at the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (ciesas), Peninsular headquarters, and member of the snii. Her research focuses on three main areas: religious diversity in Mexico, Afro-descendants and the different manifestations of racism. She was academic co-responsible of the Cátedra unesco/inah/ciesas"Afrodescendants in Mexico and Central America: recognition, expressions and cultural diversity" (2017-2021); since 2016 she has served as academic co-coordinator of workshops on the use of visual tools for social research in. ciesas, Peninsular, from where he promotes collaborative work and methodological experimentation in visual anthropology. He is a member of the Network of Researchers on the Religious Phenomenon in Mexico (rifrem) and the Audiovisual Anthropology Research Network, Audiovisual Laboratory (riav) of the ciesas.