The Ideal and What Is Actually Experienced: The Ethnography of the Ritual of the First Communion

- Guillermo de la Peña

- ― see biodata

The Ideal and What Is Actually Experienced: The Ethnography of the Ritual of the First Communion

Receipt: October 7, 2022

Acceptance: December 22, 2022

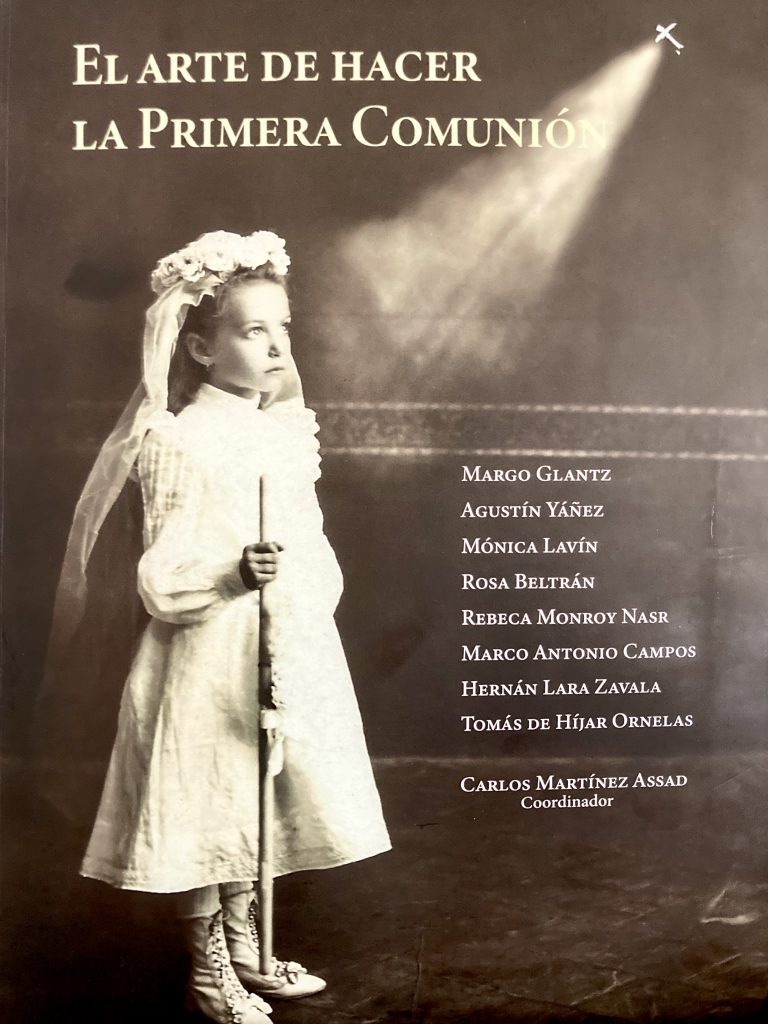

El arte de hacer la primera comunión

Carlos Martínez Assad (coord.)2021 UNIVA/ITESO/INAH/Fundación Sara Sefchovich/ Tomás de Híjar Ornelas/Jesús Verdín Saldaña, Guadalajara, 148 pp.

Some people may find it strange that a noted social historian (or sociologist-historian) like Carlos Martínez Assad should coordinate a book dedicated to the Catholic ritual of first communion. But such an endeavor will not seem strange to those who appreciate the importance of the history of mentalities, the ethnography of emotions and the analysis of rituals to understand the culture of an era and a community. The first communion of which this book speaks gives us a key to understanding the Catholic world of the 20th century, especially in Latin countries and in middle-class urban Mexico.

The word ritual (or rite) designates a sequence of public and regulated actions that is repeated periodically and carries a symbolic load, whose meaning is shared and valued by a collectivity. Its nature may be religious or secular. Religious rituals are usually endowed with a greater moral force, as they are linked to the sacred realm; that is, to a realm of unquestioned beliefs. (Sometimes it is preferable to reserve the word rite or ritual for religious sequences, and use ceremony for civic or purely social acts). In addition, anthropologists and social scientists distinguish a special kind of rituals, which they qualify as of passage from the work of the ethnologist and folklorist Arnold van Gennep (1909). Rites of passage mark the movement of individuals or groups across a threshold. This threshold can be of various types. It may refer to the movement between two spaces, as in the case of migrations. Or to the passage from one culturally significant period of time to another; for example, in rural Mexico, from the end of the dry season to the beginning of the rainy season, which is also the beginning of planting. Or the transition from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. The threshold may also concern the change from one social position to another: from bachelorhood to marital status, from student to worker, from private citizen to public official, from poor to rich, from friend to in-law, and so on.

In all rites of passage, three phases are distinguished: the preliminary or preparatory phase, the liminal or transition phase proper, and the postliminary phase, when the change is complete and the social relations of the participants, among themselves and between each of them and other people, have been modified. Different symbols usually correspond to each phase (see Turner, 1961). The situation of liminality implies being between one thing and another: previous relationships and hierarchies are no longer in force, but new ones have not yet begun to function. The awareness that "there is something that must change" may represent discomfort, even conflict, and one of the functions of ritual is often to prevent or diminish it by providing new forms of cohesion.

Now, as Rebeca Monroy Nast mentions, the administration of each of the seven Catholic sacraments (baptism, confirmation, penance, eucharist, marriage, extreme unction and priestly ordination) is in fact a rite of passage. As such, the sequence of actions that constitutes a first communion, in which a child baptized in the Catholic religion, between the ages of seven and twelve, receives the sacrament of the Eucharist for the first time, can be analyzed. In Catholic families, the first communion is announced and celebrated as an event of the greatest importance, both in religious and festive terms. Monroy's chapter and Carlos Martínez Assad's introduction provide what could be considered the official version - theological and traditional - of the sequence and symbols used, whose purpose is to consolidate the faith with new knowledge and emotions, as well as to give the communicant a new identity in the community of the faithful.

The preparation phase begins with the catechization of those who are about to receive Communion for the first time because they are old enough to do so. It is expected that they already know, through family teaching, the fundamental beliefs and prayers of Catholicism (Our Father, Hail Mary, sign of the cross, some ejaculatory prayers); but it is necessary that before receiving communion they broaden and deepen their knowledge; they should know by heart and understand what the Creed, the ten commandments of the law of God, the commandments of the Church and the list of the sacraments say. The catechesis can come from the school -if it is Catholic-, or from the parish, or from a relative more versed in religion, or from a friend who is a specialist, or from a nun in a convent who offers the service. The second phase - the transition - begins with the administration of the sacrament of penance: the first confession. In making it, the communicant has to confront alone, without the protection and guidance of his family or his instructors, his own sins - with his capacity to "do evil" - and repent of them. Then, in taking communion, he must also consciously assume the enormous responsibility of receiving in his own body, according to the doctrine of the Church, the body of Christ. This liminality - previous protective relationships are over, but those to come are not yet known - is difficult and even threatening; however, aferwards, the act of communion seeks to create a situation of security by means of various symbols endowed with this function: the white color of the robe or the ribbon on the arm represents the purity - the state of grace - achieved by confession; the candle or the candle carried by the communicant, the light of faith and of the divine presence. The baptismal vows are renewed as a consolidation of the child's membership in the Christian community. The godparents enter the scene, representing a reinforced social cohesion. And the most important symbol is the consecrated host: a round of flour that has become -transubstantiated- a symbol of the Christian community in a God who is present and consoling. In the third phase there is a social gathering, usually a breakfast or lunch, which celebrates the forging of a new identity, conscious and responsible, of an increasingly complete Christian person. Likewise, the fellowship makes tangible the reality of the relatives and friends who participate in the community of the faithful. The relevance of the ritual lives on in the commemorative holy cards and photographs that will occupy a visible place in the home.

Such is the official and idealized version. However, the book coordinated by Martínez Assad does not stop there: it includes seven narratives by well-known Mexican writers describing how different children experience the sequence and its symbols in the real world. Some narratives are overtly autobiographical; others are not in an obvious way. Nevertheless, I think that autobiographical components are evident in all of them. Agustín Yáñez's dramatic narrative - "La estrella nueva", the only one not written in the first person- dates from 1923. It paints the enthusiasm with which a little girl, Rosita, awaits her first communion: an enthusiasm shared by family, relatives and neighborhood children. One might expect an ideal first communion, but the preliminary stage becomes pathetic: Rosita becomes seriously ill and dies shortly after receiving communion. Rosa Beltrán's story, "Singular first communion", is very different: the protagonist, by an inexplicable impulse, decides to go to communion without any ceremony, which provokes the anger of her parents for having anticipated the ceremony they had planned for her and her sister. For this girl, the ritual, which does take place, is not memorable in a positive way: all the family's joy is focused on the sister, who does go to communion for the first time. Even the narrator states, "within a few days of entering, God leaves your heart."

In Margo Glantz's story, "Un viejo recuerdo rememorado", the main character is a Jewish girl. Two young Catholic girls who were teaching her and her sister English urged them to be baptized and make their first communion. The two little Jewish girls went through the whole canonical sequence in which, of course, their own family did not participate. They were catechized in a convent of nuns, they confessed invented sins, they had the sponsorship of a wealthy family that after the ritual invited them to a rich breakfast. For them, the symbols lacked theological significance, and rather than a religious experience, the first communion was a playful and aesthetic experience; however, the protagonist, in the author's voice, "retains an infatuation for medieval nuns" and "[...] especially for Sor Juana [Inés de la Cruz]". In turn, for the protagonist of "La elocuencia de las flores", the story by Mónica Lavín, whose parents could be characterized as more or less agnostic, the Catholic religion was inextricably linked to her grandmother from Madrid. She brought her closer to "a god that was brought with the [Spanish Civil] war and whom she did not disbelieve in despite the exile" and the calamities suffered in her life in Mexico. The religious experience was forged in the coexistence with her grandmother -in her "secret to radiate joy and warmth"-, in "the beauty of the flowers of the convent garden" where she was catechized, in the "mystery" of the nuns' life, in "the effort to understand something that I do not understand now" and would crystallize "in the ceremony that deserved [...] the opportunity to glimpse it, to feel it, no matter how brief". The nostalgia for those emotions remains.

In contrast, the protagonist of Marco Antonio Campos' text, who confesses to being a "Christian without a church", does not feel that his first communion ceremony, performed at the behest of his mother, has left any pleasant mark on him. Almost the only thing he remembers - with antipathy - is that he went to confession twice when he was between the ages of nine and eleven. In contrast, in the story told by Carlos Martínez Assad, "A miracle that fell from heaven", the communicant has a perfect memory of the sequence: the catechism, the confession, the ceremony, the celebration. It is a pleasant enough memory, even if it includes how difficult it was for him to understand its meanings and importance. Moreover, for him the most exciting thing - "the miracle"- was not the communion, but the fact that in those days a plane, which he imagined to be a fighter plane, had crashed in a field in the village where he lived. For his part, the character presented by Hernán Lara Zavala, in "Oblation", gives a detailed description of his experience: what he was told, did, thought and felt throughout the phases of the ritual. He associates the experience with the enigmatic image of a young aunt of his, a novice in the convent where he was catechized, whom he saw only once, briefly, beautiful and radiant in her white dress. However, the sequence ends with an act of rebellion: "I never made my first communion. The body of Christ never inhabited my soul because since I was a child I decided to keep God at a distance." Disguisedly, he kept the host in a handkerchief and kept it "in a little sandalwood box". "From then on I inhabit a world without light." Echoes of Nietzsche (2011)? "God is dead [... and] the desert is getting bigger and bigger" (cfr. Royo Hernández, 2008).

As a whole, the book constitutes an ethnographic document in which appear and combine -as Lévi-Strauss (1958) would say- several fundamental oppositions in Catholic culture: good and evil, grace and sin, the sacred and the profane, the ecclesiastical and the secular; all of them susceptible of being mediated by rituals. Contributing to the ethnographic richness are the abundant illustrations: photographs (of the girl or boy in their communion dress, alone or in a group, accompanied by their parents or by the priest) and commemorative holy cards (neo-baroque and sweetened images of Christ or the Child Jesus with the host and a girl or boy receiving it, at the moment of communion). A selection of allusive poems is included; more than literary, their value is testimonial about the transcendence of the theme.

The narratives reveal the changing role of Catholicism. Yáñez's is set in a provincial urban neighborhood, probably that of the Santuario, in Guadalajara, where his Flor de juegos antiguos (1958) also takes place; it happens six years before the religious persecution unleashed by the post-revolutionary government and shows the communitarian strength of the social sector that manifested itself against it: a sector imbued in its daily life with Catholic religiosity. The other stories take place in the 1950s and 1960s, and in Mexico City, except for Martínez Assad's, which also takes place in the 1950s in a small town (San Francisco del Rincón, Guanajuato). In these decades we find a more secularized, individualistic and pluralistic scene. The community had lost its vigor and it was the family that determined the form and value of religious rituals. Mexico's city society still revealed itself as a predominantly Catholic world; in it, first communion was important and could be endearing for those who participated; however, the decline in the centrality of religious practices that followed in the following decades was already foreshadowed.

Bibliography

Levi-Strauss, Claude (1958). Anthropologie structurelle. París: Plon.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (2011) Así habló Zaratustra. Madrid: Alianza [publicación original entre 1883 y 1885].

Royo Hernández, Simón (2008). “Nihilismo y desierto en Nietzsche”. A Parte Rei, núm. 56, pp. 1-8. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3021675, consultado el 22 de diciembre de 2022.

Turner, Victor (1961). “Three Symbols of Passage in Ndembu Circumcision Rituals: an Interpretation”, en Max Gluckman (ed.). Essays on the Ritual of Social Relations. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Van Gennep, Arnold (1909). Rites de passage. París: Émile Nourry.

Yáñez, Agustín ([1942] 1958). Flor de juegos antiguos. Guadalajara: Instituto Tecnológico de la Universidad de Guadalajara.

Guillermo de la Peña is a professor-researcher at ciesas D. in Social Anthropology from Victoria University in Manchester (UK). D. in Social Anthropology from the Victoria University of Manchester (United Kingdom). He has been a professor or visiting researcher at universities in Latin America, North America and Europe, as well as a consultant for international foundations. Among other distinctions, he has received the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Jalisco Prize in the area of science and the emeritus of El Colegio de Jalisco. His research topics and publications have dealt with the historiography of education, anthropological approaches to the study of education, the transformations and mobilizations of Latin American peasants, political culture among urban popular sectors, the history of anthropological theory, as well as the relationship between cultural diversity and citizenship.