Learning to see and feel the invisible: somatic pedagogy in alternative spiritual practices.

- Yael Dansac

- ― see biodata

Learning to see and feel the invisible: somatic pedagogy in alternative spiritual practices.

Receipt: July 31, 2023

Acceptance: December 5, 2023

Abstract

The article exposes a progressive somatic learning process aiming at the production of a sensitive body capable of interacting with non-human agents promoted in spiritual practices of New Age and neo-pagan inspiration. Contemporary rituals performed at the archaeological site of Carnac, France, are taken as ethnographic and empirical basis by considering them as sensory learning spaces where participants develop their bodily attention to verify the efficacy of the implemented techniques. The analysis shows that the main elements that compose the applied somatic pedagogy are the learning of an alternative sensory language, the execution of body techniques, the practice of visualization and the incorporation of somatic imaginaries.

Keywords: sensory learning, Carnac, spirituality, somatic experience, France, megaliths, neopaganism

learning to see and feel the invisible: somatic learning in alternative spiritual practices

This article describes a progressive somatic learning process that aims to produce a body sensitive enough to interact with the non-human agents promoted in New Age and neopagan spiritual practices. Contemporary rituals organized at the archeological site in Carnac, France, are the empirical research subject of this ethnography. These rituals are approached as spaces for sensory learning where participants tune into their body in order to verify the effectiveness of the techniques. As shown in the analysis, the core elements of the somatic learning applied in the rituals include the incorporation of an alternative sensory language, body techniques, visualization, and somatic imaginaries.

Keywords: sensory learning, somatic experience, spirituality, neopaganism, contemporary paganism, Carnac, megaliths, France.

Introduction

In the last twenty years, several researchers have analyzed the bodily and sensory dimension of the lived experience of those who participate in practices that promote a holistic conception of the human being.1 (De la Torre and Gutiérrez, 2016; Jamison, 2011; Pierini et al., 2023; Pike, 2001). The results obtained by these studies have pointed out the primacy of the sensory in the elaboration and socialization of experiences of a spiritual nature, as well as the role given to the senses as tools used to construct experiences valued as transcendent. This has revealed the importance given to the body as a space where participants register such experiences in a sensory and emotional way. Among the holistic practices analyzed, those associated with the heterogeneous phenomena identified as New Age2 and neo-paganism3 have served as ideal case studies for exploring new sensory hierarchies that value touch as a key sense for perceiving the presence and agency of summoned entities, such as energies and spirits (Rountree, 2006; Lombardi, 2023: 77). re

From anthropology, the analysis of the cultural construction of the body has boosted knowledge about the socialization of bodily and sensory experiences. The bodily approach, interested in how certain cultural practices are inscribed in the body (Blacking, 1977), emerged as a critique of the textualism characteristic of anthropology in the early 1980s.4 In the following decade, anthropological interest in the body gave rise to a sensory turn that focused attention on identifying distinct cultural patterns of sensory perception that forge human experience (Howes, 2018: 7). Such a process gave rise to a methodological orientation called "embodiment," which is strongly influenced by the work of Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1945, 1964) and the writings of Pierre Bourdieu (1977: 124). The former proposed to break with the Cartesian dualism that separated the body from the mind,5 and the second provided an approach to embodiment in which the notion of the body includes the senses, emotions and consciousness.6 The embodiment paradigm to which I subscribe was proposed by Thomas J. Csordas (1990), who analytically addresses the embodied experience that individuals have of their own body and the ways in which they use it to interact with their physical and social environment. From these theorizations, Csordas developed the notion of "somatic modes of attention" (Csordas, 1993: 138), defined as culturally elaborated ways of paying attention to and with one's own body, in environments that include the embodied presence of others. Such modes are neither arbitrary nor biologically determined, but are culturally constructed.

In this paper, I analyze somatic modes of attention that are characteristic of New Age and Neopagan-inspired practices performed at the archaeological site of Carnac. The data collected at this site serve as an ethnographic and empirical basis for addressing how participants learn to experience these activities with their bodies and senses. The goal of the text is to provide as complete and accurate an understanding as possible of the learning process that shapes the sensory experiences of the practitioners. The data presented in this article were collected by applying a sensory ethnography characterized by the systematic implementation of different tools (Pink, 2009). The categorization and analysis of the data allowed me to identify and reconstruct a process that I call "somatic pedagogy". The elements that make up this kind of progressive sensory education are likely to be identified in other ritual contexts typical of New Age and neo-pagan spiritualities. Specifically, it involves the learning of an alternative sensory language, the execution of bodily techniques, the practice of visualization and the incorporation of somatic imagery.

From an emic point of view, the objective of the analyzed practices is to access the "healing powers" of the local megaliths through the intervention of non-human beings called "spirits of the place". As in the case of contemporary animist ceremonies, such practices function as spaces where participants "learn to interact appropriately with other people, not all of whom are human" (Harvey, 2005: 17).7 The effect mainly desired by the participants is the acquisition of affective states inscribed in the emotional regimes promoted within the New Age and the culture of personal development, which are likely to generate the conditions "objectively required for the full realization of the human being and its potential" (Mossière, 2018: 65). Practices also function as space-time where practitioners establish ritualized and embodied interactions with objects (Ishii, 2012; Whitehead, 2018), which in this case are prehistoric monuments to which an "energetic" agentivity capable of provoking a transformation of identity and a personal encounter with the "other" (the divine, the sacred, the transcendent) is attributed. The practices are organized through a ritual protocol that divides them into different stages. From one stage to the next, participants progressively develop their bodily attention and pay special attention to their bodily sensations. This is how they progressively learn to use them as tools to verify, experiment and experience when and under what conditions their body comes into contact with the energy of the megaliths.

The text begins with a discussion of works that have highlighted the roles attributed to bodily sensations and the different teaching strategies that are implemented to produce and interpret them within New Age and neo-pagan inspired practices. The context of our case study is described below. The elements that distinguish these practices and the methodological tools applied are then discussed. Then, the ritual protocol that organizes the practices is illustrated on the basis of an ethnographic account. Finally, the elements that compose the identified somatic pedagogy are analyzed. By way of conclusion, I delve into the relationship that we can establish between this pedagogy and the efficacy granted to the analyzed practices, as well as the importance of touch as a primordial sense that allows the participant to affect and be affected by the summoned entities.

Alternative spiritual practices as learning spaces

The collection of ethnographic data on heterogeneous interpretations of the body, especially of the "sensitive body" as the place we are and construct in order to exist (Le Breton, 2010), has allowed us to explore the meaning given to somatic experiences in ritual contexts of alternative spiritualities. Some examples are neo-pagan ceremonies in which participants learn different somatic modes of attention to interpret certain bodily sensations as produced by non-human beings (Rountree, 2006); neo-shamanic rituals in which different sensory and olfactory experiences are placed in value by those leading the practices as evidence of a divine intervention (Lombardi, 2023: 77); and energy healing sessions in which certain sensations are presented as evidence of interaction with "invisible energies" (Pierini et al., 2023). The omnipresence of references to the body in the discourses of those who participate in this type of experiences seems to be due to the principles that organize the practices. As illustrated by the research conducted by Renée de la Torre and Cristina Gutiérrez (2016: 168) on the ritual protocol that organizes the pre-Hispanic steam bath sessions called temazcal, certain practices function as devices oriented to the production of bodily sensations through ritualized interactions of the participant with elements of nature (trees, stones, fire, water, and earth, among others).

Birgit Meyer (2006) points out that studies on somatic experience provide insights into different bodily disciplines and sensory regimes promoted by contemporary spiritual currents. They also highlight the potential of various holistic practices as spaces where practitioners discover, experience and incorporate a body of knowledge related to the body and senses that is transferable or can be applied in other contexts. The data presented in the previous paragraphs raise the following question: what are the components of the learning processes that allow practitioners to produce and experience these activities with their culturally constructed body?

Several analyses have explored how knowledge and skills associated with the body and senses develop in neopagan ritual contexts. Emily Pierini's (2016) study of the learning process of Brazilian mediums identified how actors develop skills to establish relationships with invoked spirits. Her research revealed that such learning takes the form of a multidimensional experience that is at once bodily, intuitive, performative, conceptual, and intersubjective. David Dupuis' (2018) research on what he terms "visionary learning" in neo-Shamanic ayahuasca rituals taking place in the Peruvian Amazon also reconstructed specific processes of progressive learning. His study identified the discursive and pragmatic interactions that frame the consumption of such hallucinogenic concoction and that shape participants' interpretations of visions.

Although these two studies contribute to the reconstruction of specific learning processes implemented to elaborate experiences of a "spiritual" nature, I believe that a deeper attention to the elements that shape somatic education, both at the individual and collective level, is necessary based on a sensory ethnographic approach (Pink, 2009). In search of understanding how participants produce and cultivate a body capable of interacting with non-human entities, between 2015 and 2019 I conducted an ethnographic study at the archaeological site of Carnac. Over the last twenty years, this space has become the site of numerous courses, meetings and collective ceremonies oriented towards the production and socialization of somatic experiences provoked by the physical contact of the body with the surface of prehistoric stone monuments.

Context of the case study

Carnac is an archaeological site located in northwestern France, famous for its numerous prehistoric monuments in the form of stone blocks called megaliths and tombs called tumuli (Figure 1). Various groups gather there for collective practices, generally lasting one day. These activities promote ritualized interactions between humans and non-humans that are susceptible to somatic experience. One such experience was described by Marie, a participant from the Carnac region as follows:

When I lay down on the megalith, I felt its energy in my body, in my spine. I felt the energy of the stone realigning me from the inside. That was very powerful. I really felt the energy of the place, I felt what it was doing to me (Marie, May 6, 2017).8

The practices analyzed intermingle bodily techniques9 derived from popular traditions concerning the healing powers of megaliths (Boismoreau, 1917) and holistic knowledge about the body that began to spread in France in the 1980s through esoteric magazines.10 Marie, like other participants, believes that Carnac has three main characteristics that make it an ideal place to "connect" with herself, with nature and with the universe. Like other archaeological sites converted into places of worship by those who adhere to alternative spiritualities, the megalithic landscape of Carnac is considered a "sacred natural landscape", an "energetic place" and the work of "ancient builders" who had "other" knowledge about their environment. As the following sentence illustrates, the discourses of the specialists leading the practices echo these conceptions: "The sacred natural landscape of Carnac, with its megaliths, serves as an environment for us to balance our energies" (Eric, December 13, 2015). If the knowledge of the specialists is accepted by the participants as "legitimate", it is because the former hold a moral authority before the group (Durkheim, 1992 [1902]: 25). This means that their authority only exists if it is recognized by the participants. The latter grant him consensual obedience because they consider that the specialist has knowledge about the megaliths that is susceptible of being reformulated or enriched by their own experiences and knowledge.11

The practices analyzed are not identified by specialists as "spiritual" or "ritual". They propose them as playful and therapeutic activities. However, these practices are experiences that structure and produce subjectivities and identities. Their "spiritual" potential lies in the quality of relationships and experiences that seek to produce a reunion with oneself and a change in relationships with oneself and others (Heelas, 2009: 792), as well as a search for authenticity, truth and transcendence (Mossière, 2018: 61). They constitute ritual practices because they are bearers of meanings, express a series of cultural values and ideas, put disparate elements in relation making them interdependent, are characterized by their internal dynamics and constitute devices oriented to the production and socialization of specifically somatic experiences. The notion of spirituality identified in the discourses disseminated in these practices is linked to a semantics centered on energies (telluric, bodily, emotional, divine, cosmic, universal). This vocabulary evokes the possibility of a holistic type of healing in which each participant seeks to reconnect with himself, with others and with the universe (Houseman, 2002: 533).

The practices are heterogeneous in terms of the ideology they mobilize, as each offers a different framework of interpretation. They can be based on telluric energies, Carlos Castaneda's tensegrity,12 neo-shamanism or energetic healing of the aura. The only requirement for participation is to pay the fee established by the specialist. The groups are heterogeneous, constantly changing and made up of three main types of actors. They play specific roles, respect a vertical hierarchical structure and maintain a gender order that assigns different functions to men and women. The specialist is the one who guides the participants through a protocol that organizes the practices and constructs the narratives that give them meaning. All the specialists I met were men between forty and seventy years old, most of whom lived in Paris, and had pursued higher education. The specialist identifies himself as a "shaman" or "shamanist".coach spiritual" and is rarely self-taught, as he acquires his knowledge through training courses in the field of energetic healing. The specialist offers a wide variety of practices that differ from each other by their duration, the number of megaliths to be visited and the interpretation frameworks provided. These activities are proposed on websites where the participant can choose the one that suits him/her best. The specialist's assistant is in charge of mediating the communication between the actors, avoiding the monopolization of the word, de-dramatizing a situation when there is a problem and managing conflicts. All the assistants I met were women who had a personal relationship with the specialist. The participants are the ones who pay the fee charged by the specialists, which varies between one hundred and fifty and three hundred euros per day. The objectives that lead them to invest their time, money and effort in these practices vary. In general, participants seek to live an experience capable of bringing about an immediate change in their perception of themselves, others and their environment. Most of the participants I met were first-timers, lived near Carnac and were women between twenty-four and seventy years of age with higher education. They have a common interest in occultism, archeology, astrology or personal development. The three types of actors make up what I call "ephemeral communities",13 as they do not establish personal or lasting relationships with each other.

Tools for an ethnographic study of sensory experiences in ritual contexts

From 2015 to 2019 I conducted an ethnographic study on twenty New Age and neo-pagan inspired practices performed at the archaeological site of Carnac. The aim of the study was to analyze the process of construction and socialization of experiences considered as "spiritual" that manifest themselves somatically. To do so, I focused on the situation of the bodies of the people investigated, as well as on the intersubjective environment in which they generate and interpret their bodily sensations. Following these strategies, I sought to provide new insights into the content of the "lived experience" of my interlocutors.

Taking into account that the study was conceived as a phenomenology of ritual experience in a specific context, I decided to apply ethnographic methods that would allow me to collect data on the sensory experience of the participants within the analyzed practices. At the beginning of my fieldwork I found that typical ethnographic tools, such as participant observation and semi-structured and structured interviews, were useful but not sufficient to obtain detailed data on the processes that allow participants to generate and interpret their bodily sensations. Therefore, I integrated two methods developed by sensory ethnography (Pink, 2009): somatic interviewing and sensory participation.

The somatic interview is a tool adapted from the method developed by Jaida K. Samudra (2008: 670) in her research on kinesthetic experience. It consisted of asking participants questions about the correct way to perform a certain body movement indicated by the specialist and then following their indications while they supervised me performing it. By proceeding in this way, I obtained physical and verbal responses from the participant-mentor, who recurrently corrected my body posture and movements. At the same time, I physically carried out the instructions the participant had just given me, including the corrections. During these somatic interviews I played the role of a trainee. By being observed and guided by other participants, I was able to identify when and under what conditions somatic experiences occur that participants value as indicators of the presence of "energies," "spirits," or other summoned entities.14 Sensory engagement is a tool conceived by David Howes (2019) in his study on the meaning attributed to sensations in different cultures. It consisted of using my body, my senses and bodily experiences as tools to analyze the spatial position of the investigated bodies, as well as the relationship between bodily movements and a given sensation.15 This tool echoes Hilda Mazariegos' (2022) proposal of "The embodied field diary", which includes the recording of the researcher's bodily and emotional experience. The two methods I applied demanded intense physical and emotional involvement. The data collected through the application of participant observations, verbal interviews, somatic interviews and sensory participations allowed me to elaborate a triangulation between my own bodily experiences, the somatic experiences of my interlocutors and their accounts of them.

The data collected by this study allowed me to confirm that the sensory and physical involvement of the participants is intense. The importance they attach to their bodily sensations, the uses they make of their bodies and the attention they give to their senses is constant. We could suggest that the somatic mode of attention that these practices mobilize is characterized by the uses that the participants make of their bodies and senses as tools to verify the presence of the "megalith energies" and to ascertain their potentiality. The data also indicated that, from the first minutes to the end of each practice, participants must simultaneously perform multiple tasks: they must learn to move their body in certain ways, have full control of their movements and pay attention to the bodily sensations they provoke. The progressive learning of these actions forms the process I call "somatic pedagogy". My understanding of this process is strongly influenced by the embodiment paradigm of Csordas (1990). This notion emphasizes the interaction and relationship between mind and body, allows for delving into the various ways in which religious or spiritual experience is experienced corporeally, and explores how individuals experience the social and physical environment with their culturally constructed bodies. The concept of embodiment allowed me to focus on practitioners' bodies as the existential basis for the experiences they live during practices. Like Csordas (1993: 138), I used the term "somatic" to refer to the bodily sensations that practitioners use to experience the practices in and with their bodies. His notion of "somatic modes of attention" prompted me to analyze in detail the physical and intersubjective context that gives rise to a given bodily sensation.

The sensory ethnography conducted also revealed that such somatic learning is implemented gradually through a ritual protocol composed of linear sequential phases that guide the practices, forming a general pattern followed by all the specialists I met. First, participants walk as a group toward a prehistoric monument. They then stand away from the object to collectively perform body techniques. Then, the specialist guides the participants through a visualization exercise to contact the spirits or guardians who are the only ones capable of releasing the energy of the megalith. If the practice is performed near a megalith, each participant then touches the object with the palms of the hands, chest, forehead or back. When performed near a prehistoric tomb, the participant enters the interior where he/she experiences various bodily and olfactory sensations. Finally, the participants stand in a circle near the monument and engage in verbal exchanges to compare their somatic experiences with each other. The type of somatic pedagogy implemented by this protocol is based on four main elements: the progressive learning of a sensory language, the execution of bodily techniques, the practice of visualization and the interpretation of somatic imagery. I will now illustrate these elements through an ethnographic account of a practice that was not performed in the Carnac alignments, but in a local prehistoric tomb.

Implementation of a somatic pedagogy through a ritual protocol.

In a practice run in May 2018 by Pierre, this coach Spiritual proposed that we start our activities by visiting a monument other than the Giant of Manio, a four-meter high megalith that is usually visited at the beginning of the activities. Our meeting point was a community near Carnac called Le Bono, where a prehistoric tomb called the "tumulus of Kernous" is located. Arriving at the site, we parked in a small parking lot about fifty meters from the tomb. It was about eight meters high and thirty-five meters in diameter. It consisted of stones covered by a thick outer layer of granite rubble. This structure was the tomb. The only access to the interior was through a tunnel at ground level (Figure 2).

Once we all arrived at the site, Pierre asked us to form a circle and explained that this Neolithic tomb was one of the best preserved in the region and that it was safe to visit inside. He then gave us his interpretation of the site and indicated the objective of the activities we were going to carry out as follows:

In the past, the Druids performed sacred ceremonies inside this tomb to bring well-being and vitality to individuals and the community. Like them, we will enter this tomb to realign and harmonize our energy centers, which will allow us to relieve our physical and mental ailments. It will also allow us to unblock, reactivate and re-stimulate the circulation of vital energy flowing within each of us. First, your bodies will tend to adapt to the energetic frequency of the place. Secondly, the energy of the tomb will stimulate the energetic cleansing process of your being. When you come out, you will feel better, both physically and emotionally. But first, let's do some exercises to prepare ourselves and get the most out of this experience (Pierre, May 6, 2018).

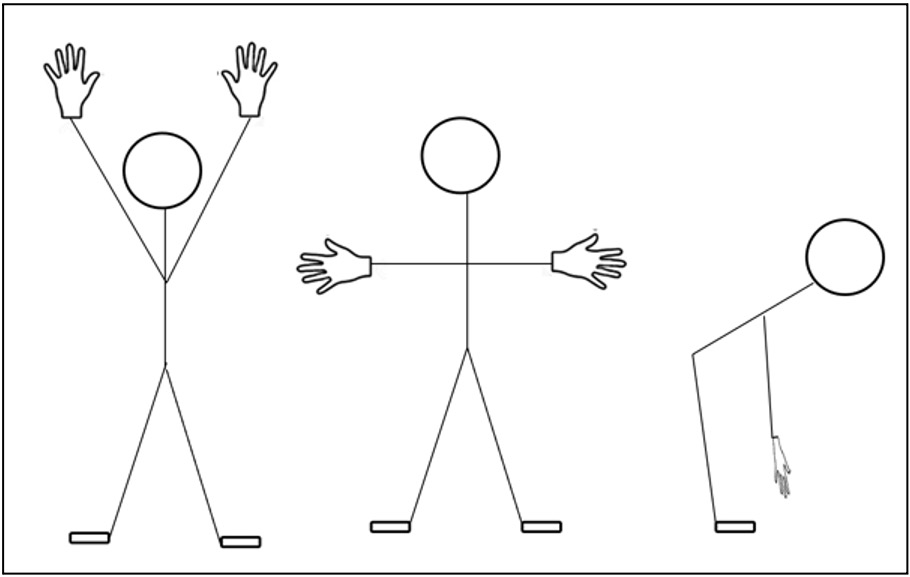

After his speech, Pierre asked us to remain in a circle and guided us through a series of body techniques that would help us to collectively identify the various sensory experiences that can be had inside the tomb. First, we were to breathe calmly and deeply, concentrating on the duration of the inhalation and exhalation. Then we had to raise our hands and arms to the sky. Next, we slowly lowered our arms to rest our palms on our head, and finally, we ran our palms down the length of our body until we reached our feet (Figure 3).

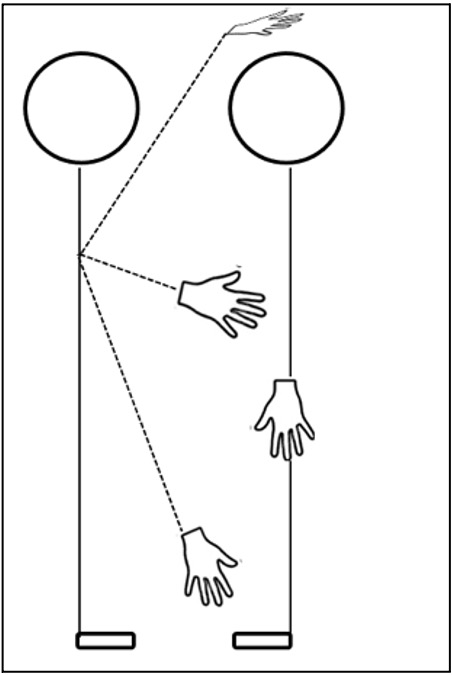

After repeating this technique about ten times, Pierre asked us to stand in pairs, facing each other, still standing and outside the tomb. He told us that one person in each pair was to remain completely still, with head upright and arms at the sides of the body. The other person was to place the palms of their hands close to their partner's body, without coming into direct contact with it, leaving about ten centimeters of distance between the palm and the other person's body. We could think of the immobile participant as adopting the role of a megalith, or a tree, or even the outer structure of the tomb. The person who could move his body had to raise his hands with his palms towards the sky, and then place them above his partner's head, without touching him. Then he had to slowly lower his palms until they were above the shoulders, then along the arms and legs, until they reached the partner's feet (Figure 4). At the end, the immobile partner recovered his mobility and the pair exchanged verbally about the bodily sensations they had experienced during the activity: lightness or heaviness in the upper limbs when drawing the partner's outline; warmth or coldness when being traversed by the palms of the other. The roles were then reversed to repeat the same exercise.

The practice of these techniques lasted one hour. At the end, Pierre told us that we were ready to enter the tomb, but first it was necessary to open the energy vortex inside the monument. To do so, we needed the intervention of a being that he introduced to us as "the guardian of the place". He explained that this entity was the only one capable of opening the vortex. Therefore, the success of the practice depended on his presence and collaboration. According to specialists, the guardians have an anthropomorphic form, lack male and female attributes, are made of light and communicate mentally with humans and non-humans. They have lived here since before the arrival of humans and like to be near "powerful" places. They are usually sitting on the ground and their gaze is always fixed on the stone. To contact him, Pierre told us that we had to close our eyes and visualize him. With our eyes closed, I listened to the specialist describe to us what he was visualizing as follows:

The spirit has human form, is made of light and is sitting on the ground. He is looking directly into the tomb. Each of you must ask him for permission to enter (Pierre, May 6, 2018).

During this visualization exercise, the participant does not simply try to imagine a "non-human" being, his goal is to interact with it without losing sight of the consciously fabricated nature of these generally invisible entities (Houseman, 2016: 232). He must therefore strive to recognize in this spirit an autonomous and dynamic being. This kind of interaction is characteristic of neo-pagan inspired rituals of contemporary new animism in which participants grant the summoned entities agency and reflexivity (Rountree, 2015: 1). Pierre considered this spirit as a being capable of relating to the space it inhabited, to humans and non-humans, and to itself.

A few minutes after he finished his speech, Pierre indicated that the guardian had agreed to our request. The energy vortex of the tomb had been opened. He then pointed out that as we entered the tomb, we would feel a tingling sensation on our skin and sensations of cold, heat, lightness and heaviness in our legs. These sensations would be even stronger once we had entered the burial chamber. The access was made in single file, quietly and slowly. The entrance to the structure led to a corridor of standing stones that I estimated to be twelve meters long, one meter wide and a meter and a quarter high. To gain access we had to tilt our upper body at almost ninety degrees. The corridor was slightly winding and the sunlight only illuminated the entrance, so we soon faced darkness. To illuminate the corridor and avoid falling on the uneven floor, the participants started to turn on the flashlight of their cell phones. When we finally reached the burial chamber, we were able to stand up. The chamber was circular in shape, about five meters square and had two-meter-high walls. Pierre was the last to enter. He immediately told us that the walls of this chamber were made of stones erected ten thousand years ago and that they supported ten tons of stones and earth above our heads. He then asked us to sit on the floor and lean our backs against the wall.

He then told us to keep quiet and turn off the lights on our cell phones. The whole group followed these instructions. As soon as we turned off our cell phones, we were enveloped in total darkness. It was then that I suddenly felt a myriad of simultaneous bodily sensations. The smell of wet earth invaded my nose and the skin on my arms and hands instantly bristled. As I inhaled, I noticed that the air inside the tomb was very cold and humid compared to the warm air outside. Since I had no vision because of the darkness, I decided to close my eyes and feel the walls and floor of the tomb with the palms of my hands. During this tactile recognition of the new environment, my palms met the hands of the participants who were sitting one on my left side and the other on my right side. Like me, they were feeling the floor and walls of the tomb. During this inspection of the burial chamber, my senses of hearing and touch gradually began to sharpen. I first concentrated on my bodily sensations and then decided to turn my attention to the voices of the other participants. Some were whispering words and phrases that I found difficult to distinguish. It is difficult for me to determine how long this moment of sensory recognition of the grave lasted. Being underground, in total darkness and silence, altered my sense of spatial and temporal orientation. My thoughts on the matter were interrupted by Pierre's voice, which suddenly echoed through the walls of the burial chamber. In a calm voice he uttered the following words:

We are here to reconnect with who we are, to rediscover what is essential in our lives so that we can feel good about ourselves and others. This moment, like all the others we will share this day, will be essential. Recharging your batteries here will allow you to take a breath, to focus on the present moment, and to experience something that you will hardly ever have in your daily life (Pierre, May 6, 2018).

After his explanation, Pierre began to guide us through a breathing exercise. This was a meditative technique designed to help us focus our attention on the physical and emotional problems we had in our daily lives. He explained it to us like this:

Close your eyes. Now you are going to reconnect with who you are. You are going to focus on the essentials of your life to recharge your batteries, feel good about yourself and others. Take a deep breath and hold it for a few seconds. Take this moment to reflect on what is causing you stress, anxiety, sadness or anger. Then breathe out gently and release the negative emotions. Remain attentive to the sensations your body feels (Pierre, May 6, 2018).

After what seemed like a few minutes, the silence that reigned in the burial chamber was gradually interrupted by a cacophony of whispered words, sighs and inhalations that reminded me that I was not alone. At this moment, I heard two participants in front of me quietly share their impressions of their bodily sensations. I heard a male voice ask, "Do you feel the cold? Is it the energies?" And a female voice replied, "It is here, the spirit Pierre told us about." Pierre's voice was heard again, interrupting the noises and the whispered exchanges. He then led us in the repetition of a mantra, "Om".

We pronounced the mantra about fifteen times, then Pierre told us to be silent to encourage us once again to self-reflect on our emotions. After a moment that seemed very long to me, he invited us to turn our cell phones back on and to get up slowly so as not to hurt ourselves and leave the tomb. The systematic turning on of our cell phones suddenly dissolved this timeless moment. The exit from the tomb followed the same protocol as the entrance. We bent our trunk again to cross the corridor leading outside. As we exited, my eyes needed a brief moment to adjust to the sunlight. Once we were all outside, Pierre gathered us in a circle on one side of the mound and invited us to share what we had felt. Florence, a psychology student who was part of the group, associated her bodily sensations to a process of acquiring the "energies" located inside the tomb. She explained it as follows:

It was a good idea to start the course here. I immediately felt very strong vibrations when we entered the tomb. The energy inside is so strong that you can't do anything else but let yourself go (Florence, May 6, 2018).

After the exchange of experiences, Pierre closed this first part of the practice by telling us that we should thank the spirits of nature and of the ancient druids who, according to him, guarded the tomb. Some participants whisper a "thank you", others did not utter a word, but closed their eyes and slightly lowered their heads in a reverential attitude. Then Pierre told us that we had to return to the parking lot to pick up the cars and head towards the megaliths of Carnac, where we would repeat the same exercises, but with one important modification. Instead of visiting another tomb, we would go to the Giant of Manio where we would each have a solo moment to touch the stone.

Identification and analysis of elements that make up a progressive sensory learning process

As I have illustrated above, the practices consist of different stages organized by a ritual protocol through which a somatic pedagogy is implemented. This entails the learning of a sensory language different from the one the practitioner is used to in his daily life. The language I am referring to mobilizes a specific interpretative framework related to bodily sensations and a particular hierarchy of meanings. Thus, sensations of cold or heat are reinterpreted as evidence of the penetration of megalithic energies into the body. Sensations of heaviness in the limbs are interpreted by participants as tangible evidence of the presence of these energies. Touch is valued as a primary sense for experiencing the efficacy of these practices (Figure 5).

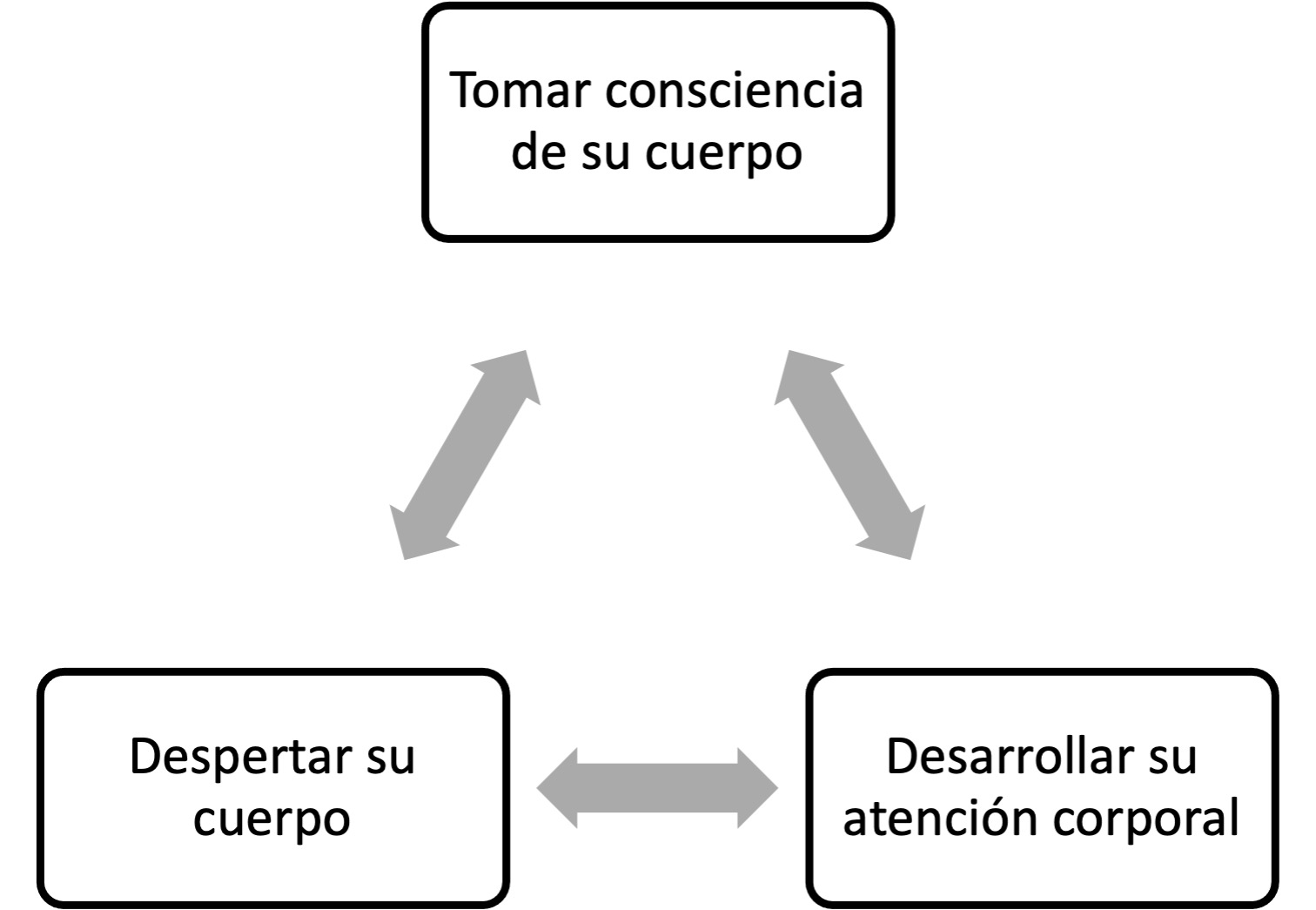

In order for the participants to appropriate this sensory language, they must respect three different tasks that are juxtaposed during the individual and collective exercises. Each participant must become "aware of his or her body" by considering it not as an object, but as a "living and sensitive body", capable of interacting with human and non-human beings (Andrieu, 2010: 349). At the same time, each one must "awaken his body" by inciting it to "feel" and interact with invisible energies (Nizard, 2020: 285). Simultaneously, each participant must develop his or her "bodily attention" (Depraz, 2014: 98) by becoming aware of the functioning of his or her body, bodily sensations, breathing and thoughts. To perform these three tasks at the same time, the participant must do all the exercises (no one can take the role of a spectator), take into account the instructions of the specialist, imitate the movements and gestures of others and concentrate on his bodily sensations. In addition, he/she must establish precise relationships between the kinesthetic patterns and the meaning given to them (Figure 6).

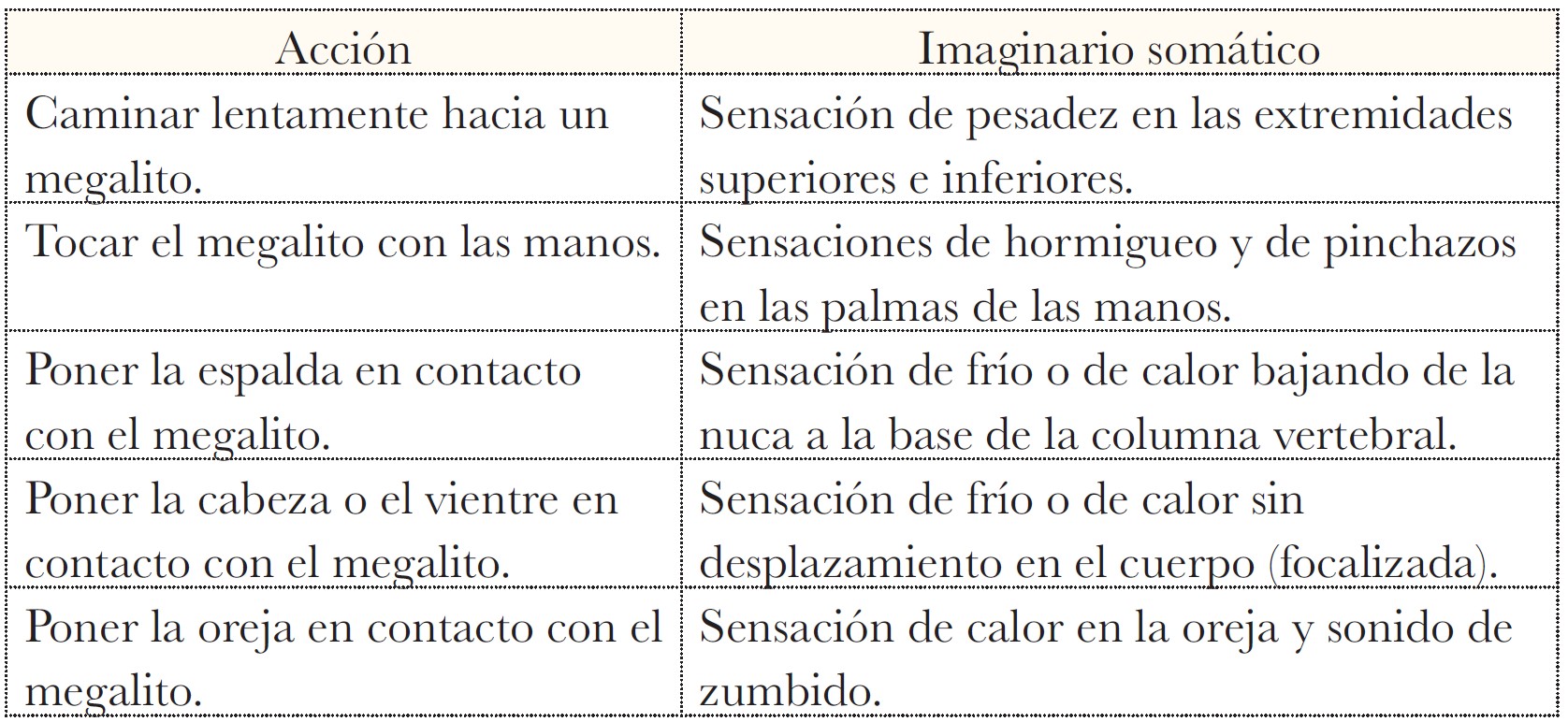

Therefore, this pedagogy also includes the incorporation of somatic imaginaries that are formulated by associating a bodily technique to a specific bodily sensation (Csordas, 1990: 18). These imaginaries are provided by the specialists (Table 1). For example, before asking participants to walk slowly towards a megalith, Jean (observation of March 5, 2016), Stephan (observation of May 20, 2017) and Peter (observation of May 5, 2018) warned participants that they would most likely experience a sensation of heaviness in the upper and lower extremities. Before touching a megalith or entering a prehistoric tomb, they also instructed them that they might feel tingling and prickling sensations in the parts of the body that were in direct contact with the stones. The data collected show that the specialists constantly evoked these imaginings, from the beginning to the end of the practices. First, the participants, most of whom are beginners, discover and assimilate these imaginaries. Then they reproduce them by putting them into words in order to share their bodily sensations with others. By transmitting these somatic imaginaries, the specialists shape the participants' bodily experiences, encourage them to adopt a reflective attitude and incite them to associate their sensations with the presence of the summoned entities. In other words, they are actively guiding, coaching and signifying the participants' experiences. Learning these somatic imaginaries allows my interlocutors to inscribe their bodies in the sensory language of these practices.

The practice of visualizing the "spirit of the place" and the "energies of the megaliths" is a meditative technique that stimulates the participants' senses and also participates in the elaboration and interpretation of their bodily sensations. When visualization is practiced in contemporary Neopagan rituals, "the physical landscape is mapped into an imaginative framework, like a guided meditation in which participants visualize themselves walking through an imaginary place or interacting with non-human beings" (Butler, 2020: 624). Visualizations can take the form of non-human beings, such as nature spirits and energies. But in the ethnographic account presented, their function is not restricted to this. Participants are prompted to visualize energies as entities capable of coming into physical contact with their body.

By way of conclusion: how to understand the relationship between the somatic pedagogy implemented and the efficacy attributed to the analyzed practices?

The efficacy that Michael Houseman (2016: 232) attributes to New Age and neopagan practices lies in their ability to allow the participant to experience a "refracted identity." In striving to execute bodily movements and experience the emotional states of "others" (e.g., the druids mentioned by Pierre), practitioners act as subjects torn between two different identities. On the one hand, the "druids" who supposedly performed and experienced these practices millennia ago and, on the other, the contemporaries who seek to feel in their bodies the effects of these activities (Houseman, 2010: 65). This process can only be achieved by establishing a particular regime of attention in which each participant must become physically and emotionally involved in the realities that these practices place value on, but without losing sight of the consciously fabricated character of these realities. Refracted identity is produced when the participant strives to experience an "extraordinary" experience.16 in which he considers himself and his body as extraordinary, without losing sight of the fact that he is an ordinary person with an ordinary body, and that this experience has been conceived and organized by the specialist guiding the practice.

Kathrine Rountree (2004) has elaborated a similar definition of the efficacy of New Age and neo-pagan practices. In her work on the spiritualities associated with the "Goddess" in New Zealand, the author stresses that participants are aware of the role of the specialist in fabricating not only the ritual practices, but also the imaginaries and discourses that shape their meanings. But for the practitioners, this in no way diminishes the effects of these activities, since by participating in these rituals they experience bodily sensations that they associate with affective states of "renewal" and "connection with nature". According to Michael Houseman (2016: 223), the fabricated character of neopagan and New Age practices does not affect the participants' experience, because within these their intentions and actions are oriented in opposite directions. Instead of associating their behaviors to their state of mind, these derive from the fulfillment of the actions entrusted by the specialist who, in the case of our study, implements a somatic pedagogy. For example, at the moment of the execution of certain actions stipulated in the ethnographic account presented, as is the case of the self-reflection exercises inside the prehistoric tomb, the participant strives to experience an affective state designated by Pierre the specialist as "of harmony" or "of realignment". In this context, the behavior of the actors does not express their state of mind, since it is dictated by the specialist's discourses. Thus, the phrases "reactivate vital energy", "reconnect with who you are" or "feel good about yourself" become prescriptions that have an intrinsic value and efficacy to which the participants seek access (Moisseeff and Houseman, 2020: 13).

The relationship between the efficacy of the practices and the protocol followed by participants is even clearer in Rountree's (2006: 106-107) study of Neopagan practices in Malta. For those who participate, the contact of their skin with the surface of Maltese Neolithic temples produces "spiritual" effects independently of the bodily sensations experienced. By touching these structures, their body and the temple "align" and merge becoming one "sacred" object. The body-to-body interaction with a "sacred energy" is guaranteed by the organizing principles of such practices, in which there is no somatic imagery. There is no uncertainty or doubt for the participants, since any bodily sensation caused by skin contact with the surface of the temple is considered as proof of the presence of "energies". The effect is tacit and unequivocal: by touching the temple and being touched by its surface, the participants establish the much desired encounter with the energies.

If touch participates in a substantial way in the verification of the veracity of an "extraordinary" experience, it is because it has become a new style of social and communal communication of the self. Since the 1990s, Michel Maffesoli has explored how the "tactile style" participates in a transmutation of values and establishes another relationship with otherness. In this sense, he emphasizes that the other "is the one whom I can touch and who can touch me" (Maffesoli, 1993: 70). This definition opens the door to a definition of the "other" as the one whom I affect and who affects me. The efficacy of the analyzed practices lies in the possibility they give to each participant to establish a reciprocal sensorial interaction with the "other", be it the divine, the energy or the spirit of nature. The identified somatic pedagogy allows each participant to learn to touch something that is visible in order to be touched by something that is invisible, extraordinary and infinite.

Bibliography

Aldred, Lisa (2000). “Plastic Shamans and Astroturf Sun Danses: New Age Commercialization of Native American Spirituality”, American Indian Quarterly, 24, (3), pp. 329-352.

Anderson, Benedict (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Londres: Verso.

Andrieu, Bernard (2010). Philosophie du corps, expériences, interactions et écologie corporelle. París: Vrin.

Blacking, John (ed.) (1977). “Towards an Anthropology of the Body”, en The Anthropology of the Body. Londres: Academic Press, pp. 1-28

Boismoreau, Émile (1917). “Notes à propos de l’utilisation thérapeutique des mégalithes dans la Bretagne”, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique de France, 14, (3), pp.158-160.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— y Jean-Claude Passeron (1977). Reproduction in Education Society and Culture. Londres y Beverly Hills: Sage.

Butler, Jenny (2020). “Contemporary Pagan Pilgrimage: Ritual and Re-Storying in the Irish Landscape”, Numen, 67, (5-6), pp. 613-36.

Castaneda, Carlos (1997). Magical Passes: The Practical Wisdom of the Shamans of Ancient Mexico. Nueva York: Harper Perennial.

Csordas, Thomas J. (1990). “Embodiment as a Paradigm in Anthropology”, Ethos, 18, (1), pp. 5-47.

— (1993). “Somatic Modes of Attention”, Cultural Anthropology, 8, (2), pp. 135-156.

Dansac, Yael (2020). “Embodied Engagements with the Megaliths of Carnac: Somatic Experience, Somatic Imagery, and Bodily Techniques in Contemporary Spiritual Practices”, Journal of Religion in Europe, 13, (3-4), pp. 300-324.

— (2021). “The Enchantment of Archaeological Sites and the Quest for Personal Transformation”, Ciencias Sociales y Religion/Ciências Sociais e Religião, 23, pp. 1-22.

De la Torre Castellanos, Renée y Cristina Gutiérrez Zúñiga (2011). “La mexicanidad y los circuitos New Age. ¿Un hibridismo sin fronteras o múltiples estrategias de síntesis espiritual?”, Archives des Sciences Sociales des Religions, 153, pp. 183-206.

— y Cristina Gutiérrez Zúñiga (2016). “El Temazcal: un ritual prehispánico transculturalizado por redes alternativas espirituales”, Ciencias Sociales y Religion/Ciências Sociais e Religião, 18, (24), pp. 153-172.

—, Cristina Gutiérrez Zúñiga y Yael Dansac (2021). “Los efectos culturales de la creatividad ritual del neopaganismo”, Ciencias Sociales y Religion/Ciências Sociais e Religião, 23, pp. 1-22.

Depraz, Natalie (2014). Attention en vigilance. À la croisée de la phénoménologie et des sciences sociales. París: Presses Universitaires de France.

Dupuis, David (2018). “Apprendre à voir l’invisible. Pédagogie visionnaire et socialisation des hallucinations dans un centre chamanique d’Amazonie péruvienne”, Cahiers d’Anthropologie Sociale, 2, (17), pp. 20-42

Durkheim, Émile (1992) [1902]. L’éducation morale. París: Presses Universitaires de France.

Harvey, Graham (2005). Animism: Respecting the Living World. Londres: Hurst.

— (ed.) (2013). The Handbook of Contemporary Animism. Londres: Routledge.

Heelas, Paul (2009). “Spiritualities of Life”, en Peter Clarke (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 758-782,

Houseman, Michael (2002). “Qu’est-ce qu’un rituel ?”, L’Autre, 3, (3), pp. 533-538.

— (2010) “Des rituels contemporains de première menstruation”, Ethnologie Française, 40, (1), pp. 57-66.

— (2016). “Comment comprendre l’esthétique affectée des cérémonies New Age et néopaïennes ?”, Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions, 174, pp. 213-237.

Howes, David (ed.) (2018). “Introduction: On the Geography and Anthropology of the Senses”, en Senses and Sensations: Critical and Primary Sources. Geography and Anthropology. Londres: Bloomsbury, pp. 1-22.

— (2019). “Multisensory Anthropology”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 48, (1), pp. 17-28.

Ishii, Miho (2012). “Acting with Things: Self-poiesis, Actuality, and Contingency in the Formation of Divine Worlds”, Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 2, (2), pp. 371-388.

Jamison, Ian (2011). “Embodied Ethics and Contemporary Paganism”. Tesis de doctorado. Milton: The Open University.

Le Breton, David (2010). Cuerpo sensible. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Metales Pesados.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1962). La Pensée Sauvage. París: Plon.

Lombardi, Denise (2023). Le néo-chamanisme. Une religion qui monte ? París: Editions du Cerf.

Maffesoli, Michel (1993). La contemplation du monde, figures du style communautaire. París: Grasset.

Mauss, Marcel (1950). La notion des techniques du Corps. París: Presses Universitaires de France.

Mazariegos Herrera, Hilda María Cristina (2022). “El diario de campo encarnado. Apuntes para una propuesta metodológica para el estudio de las emociones desde y con el cuerpo”, en F. Jacobo y M. Martínez-Moreno (eds.). Las emociones de ida y vuelta. Experiencia etnográfica, método y conocimiento antropológico. México: unam, pp. 335-352.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception. París: Gallimard.

— (1964). Le visible et l’invisible. París: Gallimard.

Meyer, Birgit (2006). Religious Sensations: Why Media, Aesthetics and Power Matter in the Study of Contemporary Religion. Ámsterdam: Vrije University.

Moisseeff, Marika y Michael Houseman (2020). “L’orchestration rituelle du partage des émotions et ses ressorts interactionnels”, en L. Kaufmann y L. Quéré (dirs.). Les émotions collectives. París: ehess, pp. 133-168.

Mossière, Géraldine (2018). “Des esprits et des hommes : regard anthropologique sur le sujet spirituel”, Théologiques, 26, (2), pp. 59-80.

Nizard, Caroline (2020). “S’ac-corps-der, approfondissement de l’attention corporelle dans les pratiques de yoga”, en B. Andrieu (ed.). Manuel d’emersiologie. Apprends le langage du corps. San Giovanni: Mimesis, pp. 272-340.

Pierini, Emily (2016). “Becoming a Spirit Medium: Initiatory Learning and the Self in the Vale do Amanhecer”, Ethnos, 81, (2), pp. 290-314

—, Alberto Groisman y Diana Espirito Santo (2023). Other Worlds, Other Bodies. Embodied Epistemologies and Ethnographies of Healing. Nueva York y Oxford: Berghahn.

Pike, Sarah (2001). Earthly Bodies, Magical Selves: Contemporary Pagans and the Search for Community. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pink, Sarah (2009). Doing Sensory Ethnography. Londres: Sage.

Rountree, Kathryn (2006). “Performing the Divine: Neo-Pagan Pilgrims and Embodiment at Sacred Sites”, Body & Society, 12, (4), pp. 95-115.

— (2004). Embracing the Witch and the Goddess: Feminist Ritual-Makers in New Zealand. Londres: Routledge.

— (ed.) (2015). “Introduction. Context is Everything: Plurality and Paradox in Contemporary European Paganisms”, en Contemporary Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Europe. Colonialist and Nationalist Impulses. Nueva York y Oxford: Berghahn, pp.1-23.

Samudra, Jaida Kim (2008). “Memory in Our Body: Thick Participation and the Translation of Kinesthetic Experience”, American Ethnologist, 35, (4), pp. 665-681.

Turner, Victor (1986). “Dewey, Dilthey and Drama: An Essay in the Anthropology of Experience”, en Victor Turner y Edward Bruner (eds.). The Anthropology of Experience. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, pp. 33-44.

Whitehead, Amy (2018). Religious Objects. Uncomfortable Relations and an Ontological Turn to Things. Londres: Taylor and Francis.

Yael Dansac (Mexico City, 1984) is a postdoctoral researcher at the Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Religions and Secularism at the Free University of Brussels. She holds a PhD in Social Anthropology and Ethnology from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. She has conducted ethnographic research in Mexico, France, Belgium and the United Kingdom. Her topics of study include ritual interactions between humans and non-humans, religion and ecology, anthropology of the body and contemporary sacralization of archaeological sites. She was a visiting researcher at the University of Glasgow and a fellow of the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions European Research Excellence Program. Among her numerous publications is the book she co-edited with Jean Chamel entitled Relating with More-than-Humans: Interbeing Rituality in a Living Word (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022).