Journalism under fire. Lethal Methods of Press Coercion During the Drug War

- Severine durin

- ― see biodata

Journalism under fire. Lethal Methods of Press Coercion During the Drug War

Received: February 19, 2018

Acceptance: May 16, 2018

Abstract

This article analyzes the coercion exercised against the press in northeastern Mexico during the so-called war against drug trafficking, based on the experiences of 10 communicators displaced between 2010 and 2015. It evidences the struggle of the armed groups in contention to control the editorial line of the media, as well as the vulnerability of the heralds for being in the middle of the firing line, for the lack of security protocols developed by the companies, and the existing links between public officials and organized crime. In this context, where homicides and disappearances of journalists go unpunished, initiatives are emerging that seek to redress their high professional vulnerability.

Keywords: war on drug trafficking, freedom of expression, forced migration, war journalism, displaced journalists

Journalism under fire. Lethal methods of press coercion during the war on drugs

An analysis of the duress that was brought to bear on the press in northeastern Mexico during the so-called “War on Drugs,” based on the experience of ten journalists displaced between 2010 and 2015. The text reveals warring armed groups' fight to control media editorial lines, in addition to messengers' vulnerable position in the line of fire due to a lack of security protocols their employers might develop, as well as existing connections between public officials and organized crime. In a context where journalists' murders and disappearances are left unpunished, organizational initiatives designed to compensate for this high professional vulnerability are emerging.

Key words: Freedom of expression, war reporting, forced migrations, displaced journalists, the “War on Drugs”.

The objective of the article is to show that during the war with drug trafficking, undertaken during the mandate of Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), 1 the forms of coercion towards the press in the Northeast2 they changed and became lethal. In the context of the paramilitarization of organized crime, a phenomenon that emerged in the Northeast towards the end of the 20th century,3 and the militarization of public security, it moved from the logic of bribery (Del Palacio, 2015) to the use of homicidal, armed violence, and disappearance to subdue the press. The armed conflict also occurred in the field of communication, where the actors in the conflict sought to control related information.

The armed conflict in question corresponds to what Mary Kaldor (2001) classified as a new war where States no longer fight each other, but armed struggles take place within the same nations due to their inability to face social decomposition; wars where irregular armies are usually faced and "in the best of cases, we witness an asymmetric combat between the State and another actor" (Badie, 2016: 18). According to Angus McSwann, reporting on guerrilla wars is much more difficult than reporting on conventional wars, and in his “experience in El Salvador, great efforts were expended to avoid or influence coverage. Lying and distortion was the routine policy of the United States government and embassy, and the guerrillas also waged a propaganda war ”(1999: 20).

In Mexico, drug trafficking and organized crime were identified as the enemy that the State had to defeat,4 and the government pressured the media not to disclose information that could endanger their operations against “traffickers” and to refrain from publishing terrifying texts - called narcomensajes - and images, for example of beheaded victims (Eiss, 2014) . These images and texts, as “propaganda objectives” of the “narcos”, circulated through alternative media, such as social networks, in particular on the Narco Blog (Eiss, 2014).

Faced with the pressure exerted by legal and illegal armed actors to control information, the exercise of journalism, which is by definition a practice of a democratic nature, was severely affected in the Northeast, as well as in other regions that were the scene of this war of a new genre, so Mexico is now one of the most dangerous countries in the world to practice this profession.5 During the last decade, attacks against freedom of expression have increased alarmingly, and journalists have been under constant siege to control information.

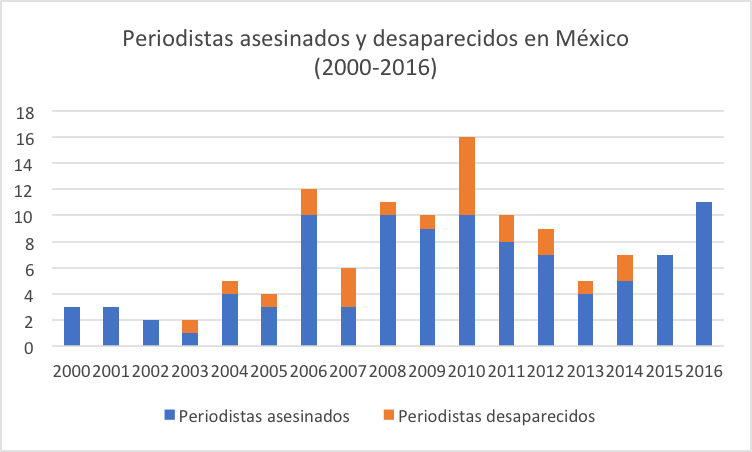

This situation calls into question the state of democracy in Mexico, and according to Daniela Pastrana, from the Periodistas de a Pie organization, no journalist has disappeared in any democratic country, unlike Mexico, where one disappeared for the first time in 2003.6 Since then, 23 cases of disappearance have occurred, and between 2000 and 2016, a hundred journalists were murdered, which represents a serious setback in terms of freedom of expression.7 Far from changing, the trend consolidated, and 2016 was the most lethal year at the national level since the beginning of the 21st century (see Figure 1).

Graph 1

As evidenced by graph 1, the period in which the attacks against the press intensified, in the form of homicides and disappearances of journalists, began in 2006, when the war against drug trafficking began. From then on, in addition to the threats, homicides and disappearances perpetrated against journalists in the northeast (see graph 2), the headquarters of the newspapers and television stations were the target of attacks with high-powered weapons and grenades. Therefore, José Carlos Nava (2014) considers that it went from a threat focused on the reporter to a corporate-organizational attack.8 As a result of these attacks, freedom of expression was highly violated, since several media agreed not to publish on subjects susceptible to reprisals; some reporters stopped exercising the profession, while others moved to protect their personal integrity.

Certainly, vulnerability in the exercise of journalism in Mexico and in the Northeast is not a new condition, and following Celia del Palacio, bribery had been a common method of information control, in the form of advertising agreements,9 gifts in kind, political gifts10 and the protection of journalists through commissions created ad hoc (Del Palacio, 2015: 33). Reporters are vulnerable to the interests of press groups and governments, but with the war against drug trafficking the forms of coercion changed and became lethal. Relationships that were previously trusted, for example, between reporters and their informants, became dangerous due to the firepower of the latter and, above all, to the existing links between legal and illegal actors that guaranteed that attacks against the press will go unpunished.

Methodological note

It should be explained that this analysis stems from an investigation on forced displacement in northeastern Mexico, which led to fieldwork that was carried out between 2015 and 2016. The study found that a significant number of journalists, and of media personnel were forced to move to protect their lives and those of their immediate family members. Given this circumstance, it was decided to delve into the specific case of the press and freedom of expression, so this analysis rests on the testimonies of 10 communicators11 Northeast displaced people. They are the raw material that allows us to analyze the form that threats to freedom of expression took in the context of the war against drug trafficking in the Northeast.

After presenting data on the murders, disappearances and attacks perpetrated against the press in the Northeast, we will show that the war against drug trafficking also took place at the communicational level and that the armed actors fought a struggle to control the editorial line of the media. Thus, once peaceful and important social relations for the exercise of journalism, became dangerous. Given the lack of response from the press groups to compensate for the vulnerability of the heralds, the communicators felt that they were disposable workers. Certain coverage became very risky, such as those related to the links between organized crime and public officials, a situation that led to the practice of self-censorship, but also to the construction of journalists' networks, with the support of pro-freedom organizations. expression.

Of murders, disappearances and attacks against the press in the Northeast

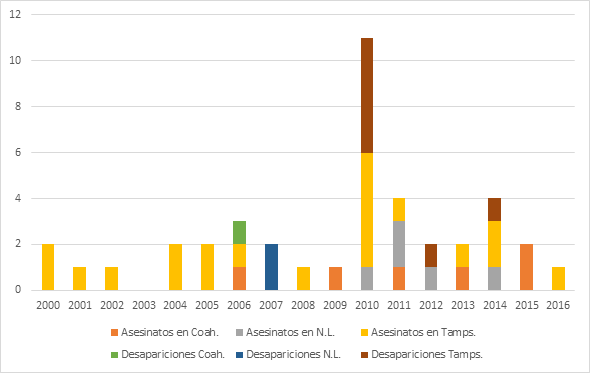

Between 2000 and 2016, the press was hit hard in the Northeast: 31 communicators were killed and 10 were disappeared.

Graph 2. Murders and disappearances of communicators in the Northeast (2000-2016)

For years, killings of journalists were limited to Tamaulipas,12 and as of 2006 this type of lethal attacks against freedom of expression were generalized to the northeast region, and included the disappearance in 2006 and 2007 of journalists from Coahuila and Nuevo León. These events were unprecedented for the union and marked the beginning of a new era for the regional press, in which homicidal violence and disappearance became a method of coercion of the press.

The three disappearances were related to organized crime, either for investigating it or for spreading messages signed by criminal groups and displayed on banners in public spaces (called narcomensajes). These disappearances, especially that of the TV Azteca Monterrey reporter and his cameraman in 2007, generated distrust in the union by raising the existence of organized crime links in the newsrooms, usually reporters from the police source. The editorial director of a media outlet in Nuevo León explains:

Suddenly you realized that there were journalists who always came to everything first and then warned the others: “hey you know what, they are telling me that there is a body, let's go” and they took everyone and then suddenly they came and took “ You know I'm going to bring dinner ”and they gave everyone dinner and so on. So since you started locating, then there was a moment when the Sinaloa cartel had its press officer and the Los Zetas Cartel had theirs, one of them disappeared, [he] was the spokesperson for Los Zetas, that's all the world knows ... He disappeared with his cameraman, they never found him, etc., but we all know that he was the spokesperson, he spoke to say "hey, let's go to such a place" and suddenly he would go and sometimes distribute money to everyone else, he was the spokesman, press officer.13

The same happened in Tamaulipas, where criminal organizations had press officers, the control of information obeyed a warlike logic and the intention of hiding casualties in the troops of their own side.

If Los Zetas are killed by 2, 3 people, because obviously it is reported, that is, it is made known that there are dead, the bulletin of the Attorney General's Office may reach you, then someone from Los Zetas has a press officer, who you can be one of them or you can be a journalist. This journalist spreads the word to everyone else. So, for example, we are going to suppose that they had casualties, Los Zetas say that this is not published, then all police editors must be notified, and editors have to notify their chief information officers and their director that this it does not have to be published.

For this reason, when in 2010 the fight between the armed actors led to an open war, the Northeast press suffered the highest number of homicides and disappearances, especially in Tamaulipas: the media and their workers were in the line of fire. At the beginning of March 2010, several reporters from different media were kidnapped in Tamaulipas; one of them was killed, while five are still missing. As the armed struggle in the region intensified, journalists, whether local or national, were not welcome. On March 4, 2010, the day after his abduction, a journalist and a cameraman from Millennium from the capital. Because it is national media, the very serious situation of the press in the northeast was widely disseminated, and Ciro Gómez Leyva declared: “In more and more regions of Mexico it is impossible to do journalism. Journalism is dead in Reynosa and a long etcetera ”(Let's document the grievances, March 4, 2010).

In addition to the disappearances, other types of threats sowed terror in the press: attacks with high-powered weapons and grenades against media buildings, with a view to exerting direct pressure on the editorial line of the newspapers.14 This practice, as well as the deprivation of liberty (known as a lift), made several media desist from dealing with any matter that had to do with security, drug trafficking and organized crime.

Between 2010 and 2013, newspapers such as Vanguard from Saltillo, The morning from Nuevo Laredo and Plinth, which is published in four cities of Coahuila, announced their decision to stop publishing information related to criminal acts and violent disputes between organized crime groups. The three journalistic groups agreed on their line of argument: the absence of conditions for the free exercise of journalism and the decision to prioritize the safety of workers and their families over information (Romero, 2015).

Just as organized crime intimidated reporters, it also attacked media buildings and delivered clear messages to newspaper owners. About the newspaper The North, a cable from the United States consul in Monterrey published by Wikileaks reports that the owners of the newspaper were threatened and came to the conclusion that they could not rely on the army for their protection,15 Therefore, they took different measures to safeguard their personal integrity.16 Despite this, the attacks against him intensified in 2012, after the publication of irregularities committed by officials of the Vehicle Control Institute in Nuevo León, who were involved in a criminal car theft ring (Wall Street Journal, August 27, 2012).

The issue of links between public officials and criminals was at the center of many attacks against freedom of expression, for example, in the Lagunera region, journalists and Televisa workers were kidnapped in the summer of 2010, when they reported a demonstration in front of the Gómez Palacio prison, after the prison director was identified as responsible for releasing criminals at night. In this context of constant siege against freedom of expression, several communicators from the Northeast moved, alone or accompanied by their families. Next, we analyze how the interest of the contending groups to control the editorial line exposed communicators to victimization because they found themselves in the middle of a war that also took place in the communicational field.

Communication war: the struggles to control the editorial line

The people in charge of defining the editorial line, whether on television or in the written press, were exposed to attempts at control by the armed actors in conflict, as part of their communication warfare strategy. They were very interested in not publishing information about the casualties of their troops, but also in taking care of the public image of their side.

The news chief of a television network recalls that for years, while he was still a reporter, they were able to address the issues of the so-called "red note" in Nuevo León without being pressured, even addressing the issue of drug trafficking. This changed with the war against drug trafficking and a sign of the fight that the cartels waged were the murders of ministerial police officers:

It was when the violence grew more, when the Zetas arrive, take control of everything and then another cartel arrives, the Sinaloa cartel, everyone will try to take control of the city and a war begins. That was what intensified the violence to power because to a certain extent Los Zetas took over the plaza with their kidnappings, payment of the floor and all that, but you did not see confrontations in the streets, because they controlled crime. When the other cartel arrives, they begin to fight the square, dispute and make war.

In this context, criminal groups began to worry about the handling of information related to their struggles. Los Zetas had colluded with police and some journalists, who acted as liaisons in newsrooms. While he was a news director for a television station, one day a member of a criminal group contacted him on his personal cell phone to inform him of his arrival in the city and demand loyalty:

A guy spoke to me who told me “look, I'm so-and-so, they nickname me so and I'm talking to tell you something, it's like an invitation or a warning, however you want to take it. We are from the Sinaloa cartel, we have just arrived in Monterrey, this is going to get very hard because we are going to fight the square, we are going to run these bastards ", and I don't know what and:" We are just talking to you so that Do not take sides, if you are collecting money, you have a commitment with Los Zetas, right now you have to leave it. If we find out that you receive money, you have a commitment to Los Zetas, we are going to kill you. If I realize that someone from your people receives money, has a commitment, we are going to kill you ”. In other words, it was there that I jumped up and said: "Wait for me, it's perfect, it's fine, but because I'm going to answer for my people, it's fine, I have control over my reporters, but I don't know what they're doing to the time they leave work ”. I told him: "I'm going to make it very easy for you, if you, all my people know that they have to be honest, that they have to live with their salary because here the company policy is that that is not allowed" and it was the True, that is, the company had a very strong policy in this regard. Why? For survival, you cannot allow someone to be with the narco because we are all in danger, so you know that, nobody, I always told them, nobody took money or commitment from these bastards, for survival. So I told him: "yes you, at a certain point you know that someone on my team receives money from someone of you or the other and you tell me, I'll go personally and give it to you so that you can talk to him." Ah! Well perfect, and then he told me again: “if you come back, we know” that I don't know what, “yes it's good, yes, clear the message, bye, bye”. I found out, that's how they talked to everyone, to me, to the one from Multimedios, to the one from the North, they spoke to all of them directly about the Sinaloa cartel, I suppose that they also spoke to the police and that's when the war began, that's when the time of more violence, they began to fight, they began to fight for municipalities, they came and killed the police who charged with those, they began to corrupt policemen for their side and it was a disorder, it was a war.

The war was also communicational and after this first call, Federico's "ordeal" began, who was the subject of other calls asking him to cover homicides and disseminate drug messages:

A psychosis and stress started that you have no idea, because as there were two sides, pretend that these guys who called me on my phone because they already had my phone, I changed it about twice and they kept talking to me on my phone, they managed to get, then a side would talk to you, the Sinaloa people would talk to you to tell you: "Hey, we're going to throw some dead in that part and we're going to put a narcomanta, a message, so that it goes on the air." And then Los Zetas would talk to you on your cell phone and they would tell you: "hey they threw some dead in such a part, that the cardboard does not come out." Then some told you to get out and others to get out.

They wanted to get the most out of television coverage: “The drug traffickers were very media, they were going to carry out an execution and they did it before 10 in the morning so that it would go live on the news or they would talk to you: 'You know what? at 7:30 we are going to dump a corpse in that part ', because they knew that the news was on at that time and you were taking it live ”.

Faced with the criminals' strategies to control the editorial line, the press groups in Monterrey met to agree on a common action: “It was when all the media made the decision, you know what, we are not going to publish any narc messages from anyone. Why? Because you were just being a spokesperson, then it was like more likely that they would accuse you that you were getting something out, so we all agreed that we were not going to get narco-messages anymore. "

Likewise, the editorial heads of different media communicated to comment on the infiltration of the newsrooms by journalists who acted as liaisons for criminal groups. On two occasions, Federico had to deal with this situation. Once, a member of a criminal group called him to report that one of his workers was a liaison for his opponents:

He spoke to me and said, "Well, do you remember that you told me this?" yes, well, so and so "charge with Los Zetas and tell him he has 24 hours to leave the city if we are not going to kill him." So I said, you know what's up, I remember we were in a meeting and we were all who made the news decisions there, and he was talking to me through the nextel. I put it on loudspeaker so that everyone could listen, everyone was listening: "hey you know, well look, don't fight, right now I'll give it to you, let me talk to him." I sent him to speak, I told him: "Come, you have a serious problem, you bastard, I'm going to pass you on to someone" and he said "you're charging" like this, "we have the information", so much money, so and so gives it to you, like this , That way. The guy changed colors and said and "we are from Sinaloa and if you don't leave in 24 hours we are going to kill you." The kid, pretend that, yes, I let everyone hear, because I didn't want them to think that it was something mine or that I don't know or I wanted to run it for something else and we were the team that made the decision, the bosses go, I decided, you know what, that everyone listen and finally the guy did not recognize it, not because, I said: “look, you don't have to check anything for me, these are the ones that have their sources and they are the ones that say , I'm not going to save you from coming to kill you bastard and if you did wrong, you got involved, under your responsibility, then you know what you want to do, you want to stay here, there is no quarrel, but the guy is telling you that in 24 hours they will kill you ”. “No, I better go”, well there among all of us, at that moment we collected money, we all gave him, the guy left, he never returned, he left for the United States, now with the doubt and all that later we investigated and effectively he did charge for drug traffickers, he was involved, they would have killed him.

When on another occasion he discovered that a member of his team was in collusion, the company defined a personnel readjustment policy: “I went, I talked to my boss, the CEO, you know what, we have this problem, this guy is infiltrated and I told him: you know what, I think he is not the only one, although they are not the spokesmen, but they charge with the other cartel. Then my boss told me: "you know what's up, we're going to organize a personnel readjustment, for financial reasons of the company" and we include those men, "but we have to include more people, no way", and a readjustment was made of personnel from the entire company, from each department we took one and included them, and that's how finally there was no problem or anything ”.

The editorial directors were between two fires, because just as they received calls from one side, they received them from the other. One day they looked for him on behalf of his opponents, while the channel's reporters were on the air, reporting a police chase:

They record where a truck crashes, all the guys with guns get out, the police arrive, arrest them, handcuff them, put them lying down like that into a patrol car. So all that video you know, let's go and get on and start narrating: "We are here, there was a persecution", we put the video where they are raising the guys in handcuffs, all beaten and at that moment I receive the call from that guy, He tells me: "immediately take what they have right out of the air" Who's talking? "I'm El Chusco", your son, I don't know what and "if you don't take it out, we're going to go to the canal and I'll pick you up and everyone there." Oh bastard, well I ran and immediately get that out of the air, well thank you very much goodbye, we did not go through it again.

Stress was at its peak: "One told you one thing, the other told you another, you took care of the backs of your colleagues and it was terrible." They also did not know how to cover the security news, it was no longer possible to say the last letter of the alphabet, nor to report police abuses, even car crashes. The censorship was radical.

Two events contributed to increasing uncertainty and prompted Federico to make the decision to leave. Twice the television station was subjected to grenade attacks, for which it was assigned bodyguards. In addition, the day a colleague was "lifted", Federico called a high command of the police to ask for help, however, he replied that by protocol they had to wait 30 minutes to intervene. The collusion of the police with the criminals was such that public security was non-existent.

This situation greatly impacted his personal life and his wife asked him to change his job, since on weekends they went out escorted for a family walk:

It was very difficult, very difficult, imagine, on weekends going out for a walk with them with a truck in the back with armed guys. You went to a restaurant and everyone stared at you because the guys were there, that is, change your routine. When all this difficult time passes, the grenade, the second grenade, the kidnapping of the colleague, the escort, all that, I already began to think about, you know, I want to change my life, that is, it's okay, we already want it, Here we already gave everything we had to give, but I no longer want to live with that uncertainty. So, is that you went out and turning around, you did not know if one day, a guy was going to annoy something of what you published, etc., it was as I said, a total disappointment because you felt unprotected because the authority had no power. Well, how are you going to feel after the guy tells you half an hour to wait for him to leave, when you are asking for help? Cases like that I can tell you many, in which there is a disappointment, a personal insecurity, I don't know, finally I said well, I'm going to start looking for a way to […] look for another [option], I say, within my work , but to go elsewhere, I began at that time to see options, to talk to friends, to see where I could go from here, get out of here and finally found a job in the United States.

According to Rosana Reguillo (2000), fear is a primary response to risk that is individually experienced, but socially constructed, and is accompanied by the need to explain the fear experienced. In this testimony, we can see very well how his feeling of insecurity - perceived individually - was built on the basis of social facts, such as the coercion of criminals in the treatment of news coverage, the collusion of the police that expanded the capacity to action of organized crime and guaranteed their impunity, and the repercussions on the personal and professional. These were so severe that Federico had to travel outside the country to exercise his trade, which precipitated his marriage relationship to a impasse. He was forced to face the possibility of being executed: “I did not leave because he spoke to me and told me, you have 24 hours to leave, it was not like that, but I did flee from living in stress, from living in the midst of anxiety And in the midst of those threats every day, that I dreamed of, I dreamed that they killed me, I dreamed that they executed me, I dreamed of my truck full of bullet holes or I saw an execution and I said hey, I can be there one day, psychologically it will affect you ”.

The dangerous relationships of the heralds

Let us now see how social relations, once peaceful and important for the exercise of journalism, became dangerous. In this communicational war, criminals used reporters as heralds to transmit messages between one side and another, and those who exercised in the street were exposed to high-risk situations, especially when they reported security issues, which requires maintaining good relations with the police officers. When most of them colluded with criminals, their situation became dangerous: “They were no longer policemen, they were criminals in uniform, then the same police began to threaten people, journalists, they began to collaborate with crime, to participate in kidnappings, to protect cargo, safe houses, so that's where the decomposition basically started: who did you go to? "

Arturo is a reporter in the Comarca Lagunera, and was displaced for refusing to publish a photograph at the request of a criminal. This was a childhood friend who worked as a photographer at the police fountain. During that time he had such good relations with the personnel of the Federal Police and the PGR that he began in drug trafficking by accompanying them in the seizure operations where they supplied drugs. This is how he stopped working in the press and became a capo. When years later they met again, his childhood friend confided to Arturo that “in Tamaulipas he had mines, he had gas stations, he had a bar, here in Torreón he had bars, he had dating houses, they called him massage rooms, and in fact the girlfriend was the one who managed his business of the rooms ”. His friend had changed, was high in the criminal hierarchy, and was acting arrogant. In his role as a mafia boss, he offered him: "When you need money, you need something, here are my employees, mark him and he marks me, and I hope he never offers me, that's the way it was." Some time later, he looked for him to contact the media where Arturo worked, then the situation became difficult to handle. One night he called him to ask for the name of his boss, and he reluctantly pointed it out:

"It's that I need you to do me a favor, we're going to hang some dead people and put some blankets on such a Boulevard, in such a location, at such a time, I want this man, your director, to send someone to take photos, so that publish ”and I said“ let's see, wait for me, if I already gave you his name, talk to him, he's the boss ”. "Well, I dialed him, I already know his phone number, but I wanted to know his exact name to tell him by name" and I said no, because it started later with pure messages "you know what, I need you to do me a favor, to At 4 in the morning we are going to put those bodies between the bridge and for you to go and take the photos ”and I started to say no and every five minutes he would send me one message and another and after another. What I did was that I dialed my boss, my director, we fought, because he said why was I putting him in, why did I put him in, oh me: “they are asking me about you”, he practically gave me a kick in the butt: "fix yourself as you can, don't mess with me."

He answered the capo's calls, he offered him money and they argued about the value of their friendship, until he threatened to go after him, his wife, daughters and parents. He knew where they lived.

In one of those he exploded: "Look, very easy, right now I send some guys out of your house to take your family out if you don't do that, at the end I already know where you live." He even begins to complain to me: “Why are you doing this to me? Why do you steer me to do this? I don't want to do this with you or I'm going for your dad, also for your mom and your sister, I know where he lives, but do me that favor. " Total: "you know that, it's fine" I said: "where do we meet to go and take those photos?". "Ok, right now I mark you." At that time, I was walking near the house of one of my sisters-in-law, a sister of my wife, I got my name, about a block away I left the car, I got to the house, I scared them because it was already two in the morning, the Her husband and her, I start talking to them like this in broad strokes and I entrust my family to them: "You know what, I'm going to do this and this." So they did not understand, look is that it is very easy, well, I already explained: “they are from a group and they are going to put on the blankets, if the group of rivals finds out that I was the one who did them that favor They are going to give me a flat, that's how they spend it and this is what is going to happen, so I come to entrust my children and my wife ”. And when I'm there with them, they mark me, and when they mark me, I answer: “you know what, everything is suspended, until tomorrow because the boss I don't know what, he didn't like exactly what the blankets said and the bodies that are still there who knows where, they have not brought them here yet, it is suspended, but for early tomorrow ”. No, my soul returned to my body, I went home, I took my family out. The next day, which was Monday, I arrived at work at 7 in the morning, the attorney arrived, the managers arrived, they didn't even let me show them the messages because there were many messages threatening me and them and several, the first thing they told me : "Have you already grabbed your family? Get out of here." "No, the plan is already in place, I need resources to leave here, because it is something we have here, I cannot live abroad with my family." "Do not tell us where you are going, but we give you to deposit so much more per week."

Although Arturo was not from the police source, the friendly relationship woven in childhood was exploited by the now delinquent to coerce him. Not wanting to participate in the exchanges of favors, typical of friendship, the boss ended up threatening him, accustomed to reaching his ends by this means. Arturo left the city with his wife and children; some relatives hosted him in Zacatecas and Matamoros. Weeks later, when he learned that the capo had been executed, he returned to work at the newspaper and realized that his colleagues did not know the reasons for his absence, believing that he had gone on vacation. The newspaper had even sent another reporter to photograph the bodies and the message. Their forced displacement had not led to the development of a security protocol or protection strategy for reporters.

Disposable workers? Violence authorized by companies

For José Carlos Nava (2014), security protocols were not adopted because the media is a business that should not be harmed: “In most companies, there has not yet been a formal space for instruction and implementation systematic and organizational security protocols. It seems that the message is: the medium to your business and the reporters to the loneliness of high-risk coverage ”(2014: 155). Experiences like the one we reviewed increase reporters' feeling of helplessness and make them feel like disposable pawns.

The media are companies that have a responsibility for security. By not adopting ethics policies to maintain the independence of the environment and nor security protocols, they minimize the risks of their workers and favor them to feel that they are “information workers”, as observed by Karla Torres (2012) in Nuevo León. "Yes, we are workers, we are the ones who matter the least in the newspaper and we are the ones who work the most." The journalist even heard rumors in the company that "the owner of the newspaper stated in a meeting that he wanted something to happen to one of his reporters to exploit the image of the medium" (Torres, 2012: 56), a rumor that expresses the feeling of being sacrificial on the altar of profits generated by the coverage of the war against drug trafficking.

This was the sentiment of the correspondent of a national media, who resigned from his job in 2011 after his editorial chief seemed not to understand the risks associated with the coverage of topics related to organized crime, in response to his request to investigate the links between the world. of politics and crime. In his resignation letter, he shared his "disappointment with some company executives" and denounced that: "The miserable salaries paid to correspondents reveal how little serious they take the dangers of reporting on the situation of violence that the country is experiencing. On the other hand, the demands are high, they demand a large number of stories and reports with first-rate sources, it seems that they do not understand that first-world journalism cannot be demanded by paying third-party salaries ”.

Thus, the conditions of extreme vulnerability to which the displaced communicators were exposed also refer to structural factors that contributed to building their feeling of vulnerability and lack of protection. In accordance with Del Palacio (2015) about the situation in Veracruz, in the northeast also "To the violence exerted against journalists must be added the government pressure that is placed on them through the owners of the companies themselves: to) unjustified dismissals; b) be changed sources of information without explanation; c) that the information be handled in a 'way' and 'taste', of the General Directorate of Social Communication of the State Government; d) that they 'download' notes that make the government look bad from the news portals ”(2015: 33). In other words, the owners of the media are actors who keep journalists in a precarious job condition: “All these forms of violence and pressure have daily job insecurity as a context: to) non-professionalization; b) low salaries; c) no job security or medical assistance; d) lack of security protocols; and) no labor exclusivity (they must work for various media) (De León, 2012).

Dangerous Coverages: Public Officials and Organized Crime

As the correspondent of a national media explained in his resignation letter, covering the links between the world of politics and crime is highly dangerous. In addition to being used as heralds, the communicators were exposed to threats and violence when they exhibited the corruption of public officials, and their participation in organized crime. Sometimes the notices were subtle, for example, when a group of journalists from the Lagunera Comarca leaked a list of 46 fired municipal police officers who received bribes from criminals. The next day, when a journalist followed up on the note and went to the Director of Security, he warned her: “You should be more careful, right? Because you are putting me at risk and if something happens to me, you are going to have the responsibility ”, then he felt indignation and let him know in command. However, in their midst they minimized the fact: “I felt that the environment was strange and that well then I realized that I did not really have the full support of the media for which I worked. And maybe they didn't do it with intent, maybe they didn't even know how and finally, we as reporters are the ones who carry the feeling of what happens in the street and we had bosses who have never come out to report ”.

In Tamaulipas, a journalist from Ciudad Victoria was threatened for publishing a note explaining that a group of merchants from Moroleón, to whom the municipality had not given permission to sell, had a permit from Los Zetas. Upon revealing the links between the union and the criminal organization, they spoke to him on the phone on behalf of Los Zetas to demand that he not be "getting on their land." A year later, she was threatened again when she published that a leader of the bureaucrats, who was expected to be reelected, had a contestant: “As this woman is a Los Zetas protégé, Los Zetas didn't think so and they sent me to paint the car […] said that if I continued to fuck they would rape and kill me along with my daughter ”. He immediately organized his trip to the Federal District, where relatives lived.

Other colleagues received no notices, and were simply kidnapped. This happened when a reporter and two cameramen reported a demonstration outside the Gómez Palacios prison, after the director was accused of allowing the criminals to go out at night. Unlike other events, these events had national coverage because the kidnapped reporter came from Mexico City. It was the summer of 2010, tension was at its highest in the Lagunera region, and the killings that occurred in bars in Torreón and in Quinta Italia between January and July 2010 had left citizens in fear and an official balance of 35 homicides in total (Gibler, 2015), but according to a reporter, the balance was higher: “In the Las Juanas bar there had been eight deaths, but not really, because people say that the Red Cross ambulance was full of bodies […] It was the inauguration, it was full and they began, they got out of the trucks and those who were at the door because they killed them, and they entered as they could and they gave them all, everyone, everyone, everyone, everyone, they say that there were more than thirty, thirty-something that time and many wounded ”. The official gazette did not reflect the size of the massacre.

Suddenly, through a video posted on social networks, it was disclosed that the perpetrators of these crimes were imprisoned in the prison, but that the director let them go out at night, even lending them weapons and vehicles from the Cereso (Center for Readaptation Social). When she was removed from her post, a riot broke out and the relatives of the prisoners demonstrated outside the prison. From Mexico, a team was sent to cover the news and broadcast it in a weekly analysis program. As the work team was incomplete, support was requested from a local chain to provide the services of two cameramen.

The first cameraman says that after interviewing the mayor of Gómez Palacio, they went to the prison because: “there was a demonstration out there, of people asking for the return of the director, because she was a very human director and so on, and inside they were the bullets, because I remember that a carriage of the Semefo (Forensic Medical Service) entered, and I recorded all that and the same police officers who were there guarding. In the midst of the climate of disagreement, "there were many policemen, soldiers, federal officials because we felt very safe doing our work there, we did, as I don't know, maybe ten interviews and there they gave us three in the afternoon." Then a cameraman from the defense team called to let them know that he had arrived at the airport, and they decided to go get him. But on the way, a group of armed men stopped his car: “they caught us and picked us up and then the nightmare began”.

They had kidnapped another cameraman from Torreón that same afternoon, and with the journalist from Mexico they added three kidnapping victims. For three hours, they were tied up in a car, alternating questions about "who do they work for", hitting and inhaling marijuana smoke. Later, they were taken to a safe house and burned the journalists' cars. The Torreón cameramen were imprisoned for six days, while the journalist from Mexico City released on the fourth day: "They were interested in him because he had the videos and they wanted them to broadcast them." They were detained along with two policemen and a taxi driver, and during this time, they experienced anguish and pain, even more so on the penultimate day when they were beaten with wooden boards. One was injured in the head.

When they were released: “The police from Mexico City took us there, they had us at a press conference that we did not want, we did not ask, you see. They had everything ready for, pos to mount the shows that García Luna was riding,17 the whole theater. We were in Mexico for about twenty days, and yes, first kidnapped by the drug traffickers, and then kidnapped by the police ”. This cameraman was convinced that acting around his release was suspicious, so he decided to go to the United States, where a relative offered him accommodation and contacted him with an immigration lawyer to request political asylum.

His other partner stayed three months in Mexico City, obtained the support of the owners of the media and the union while he was there and to organize his return to Torreón. They offered him an “inside” position and got him a rental house, because he didn't want to go back to his old home. Despite the insistence of the Ministerial Police, he refused to try to identify those responsible: "The people of the Public Ministry wanted me to identify them by force, how did I want me to identify them if I have never seen them?" Today he feels a deep gratitude to God for being alive, for the policemen who rescued them, the owners of the newspaper and the union.

Whoever requested political asylum was very disappointed to realize that during their kidnapping they were being watched by a police patrol:

We are pawns in this political thing, they moved us to where they wanted, we who had to be there on that day, and it is nothing more than the power vacuum and the ungovernability that exists and the relationship that exists between the different police corporations with the narco, in this case, because they already act as the armed wing of the cartels. They are their workers and in that context, because we had to lose, because there was no one to protect us, we felt very protected that day because there were elements of the army, ministerial and federal police, and preventive police, and it turns out that they work for them. So when there is that relationship, then who do you turn to? To no one, because they are the ones who should give you protection and unfortunately it was a city without law or the law worked for a certain cartel, for some, for Los Zetas, and in Gómez Palacio, in Durango for El Chapo. So that's what it is, that happened to us because, due to the lack of governance and because the police forces colluded with the cartels there and well, I understand them because they pay them, they pay them better and the troubled river, fishermen's profit, the policemen also get involved. kidnappers and extortionists returned.

To operate, organized crime requires support at high levels in the public function, beyond the police, and in his opinion, with his kidnapping a media coup was achieved that allowed changing the information agenda and hiding this support from the highest levels :

One piece of news kills the other, so when they kidnapped us, and we were the news, she was no longer the director of Cereso who was blamed for the inmates going out to kill people in Torreón, so they thought it very well, the television station, the The government and all of them agreed. He was there even talking about the governor of Durango that he had appointed that director, they dealt with many big names, then with the kidnapping of us, the media forgot a bit and also the people, the news of the director of security, the director del Cereso, so they did well. So that's also why they didn't kill us, because we had nothing to do with it, that is, it was a negotiation, that's why I tell you that we are bishops, like pawns in this whole chess game and because we are innocent victims of each other's interests. .

Final thoughts: self-censorship and union organization

During the so-called war against drug trafficking, media workers found themselves in the line of fire, among armed actors seeking to control the editorial line. They threatened editorial chiefs and reporters with death, assassinating 31 journalists and disappearing 10 in the northeast, and carried out attacks with grenades and high-powered weapons against the buildings and staff of the press groups. In this context, several communicators were forced to travel to safeguard their integrity. Only half continued working in the journalistic medium, and the other was doubly displaced: from their living space and from their profession. Those who left the job were reporters, but not the cameramen and editorial chiefs, as they were the most vulnerable to violence deployed by organized crime.

The experiences we analyze remind us that, according to Carlos Flores (2013), organized crime is a broad network of government corruption for the lasting operation of the criminal group, which includes conventional criminals in charge of developing the illicit activity, high-level politicians who select to those responsible for public security institutions, as well as members of these corporations, responsible for subordinating and disciplining criminal actors. For this reason, journalistic coverage of the links between crime and the government became dangerous, both for reporters and editorial heads, as well as for newspaper owners, who had social and economic resources far superior to the former for their safety. personal.

While the government of Felipe Calderón managed to get press groups to agree in March 2011 not to publish texts and images that account for the lethal power of their opponents (Eiss, 2014), in the northeast armed violence, homicide, and disappearance They were coercion methods that entailed transformations in journalistic practice and affected coverage by generating explicit censorship, as was also reported by other analysts (López, 2015; Nava, 2014; Torres, 2012).

For example, after the kidnapping of journalists in Gómez Palacios in 2010, a reporter from the Comarca Lagunera explains that her boss asked her not to address security issues. At this time, “there was no longer someone to cover security, that is, the security things that were covered were like 'They deliver patrols to the police' or 'They give uniforms', things like that, in fact even if it were that, many reporters from security were waiting for the press release, because even going to cover, going like this to Public Security, no, it was the worst, that is, entering Public Security, you felt like they are looking at me and they are pointing at me, it was very tense ambient". The worrying thing is that, five years after the events, the trend was not reversed, rather this kind of censorship was normalized: “Right now that I am in charge of the area, I am still the same, I still do not get anything from security, very important issues. administrative issues that have to do with police corporations, in fact, I have focused a lot on handling more social, business, to give it another twist. […] They give a voice to issues that were not given before, to civil associations, universities, business chambers and as I follow that line of being very social and leaving politics a little bit and then security, I don't put anything in ”.

Although self-censorship is adaptive, it is complementary to the emergence of union organization forms. The kidnapping that occurred in Gómez Palacios in 2010, by affecting a national media outlet, caused the Federal District to turn its gaze to the north. For Daniela Pastrana, from Periodistas de a Pie, this was a “turning point”, and in August 2010 the #LosQueremosVivos demonstration was organized, also in the context of the visit of the rapporteurs of the Organization of American States (OAS) and the UN. Then, the organization undertook specific support actions, such as a Christmas collection for asylum seekers in El Paso. Later, they developed actions to work with journalists from Veracruz, the state with the largest number of displaced journalists. These actions made the problem visible and attracted new international support, with the arrival of Freedom House in Mexico in 2011, the year in which the organization classified Mexico as a country not free to practice journalism.18 For its part, at the federal level, the Special Prosecutor's Office for Attention to Crimes committed against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE) was created in 2010 and the Protection Mechanism for Journalists and Human Rights Defenders in 2012.

In the northeast, national and international actors in favor of freedom of expression gave training to journalists, for example, in Piedras Negras, when the area became unsafe, at the request of reporters, in order to know how to protect themselves in their professional practice : "They explained to us that it is completely wrong to hide things, that there must be communication, maybe have a person to whom you tell where you are going, how to move, what you are doing." Freedom House, for its part, gave courses that led to the creation of an organization of journalists called Voces Iritilas in June 2014, which contributed to an incipient practice of union solidarity in the Lagunera region. A reporter explains that the organization pursues two objectives: “To be protecting ourselves for security reasons, or rather supporting ourselves, supporting ourselves, for example now that Rubén [Espinoza] has happened, we made a position for what had happened, but also there is the training side, that is, training in all senses, not only for security reasons, but also even from writing, photography, management of social networks ”. Despite the obvious progress that this represents, few colleagues who participate, who are stigmatized by the statements they issue against attacks on freedom of expression. In this conservative environment, in 2015 Freedom House collaborated in promoting the Network of Journalists in the Northeast, which brings together journalists from Tamaulipas, Coahuila and Nuevo León. It held several meetings in favor of the training of its members, supported threatened colleagues, and spoke out publicly to denounce the attacks on the press, thus gaining visibility that they had not had for years.

Finally, in 2013 there was a change in the government narrative about drug trafficking with the government of Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018), which exerted pressure in April 2013 for the adoption of a new narrative on security issues (Eiss , 2014). The situation of journalism in Mexico continued to deteriorate, since despite the creation of FEADLE, the impunity in which the homicides and disappearances of communicators remained has not been compensated, and no case in the Northeast resulted in a sentence. This impunity has consequences: “The lack of results in the attention to cases of grievances against journalists and the media, by the authorities in charge of justice, as well as those in charge of public security in the country, has generated, to a large extent, that they remain unpunished, in addition to causing the violence suffered by them to increase ”(CNDH, 2013: 106).

Bibliographic references

Artículo 19 (2016a). “Periodistas asesinados en México”. Recuperado de http://articulo19.org/periodistas-asesinados-mexico/, consultado el 22 de octubre de 2016.

Artículo 19 (2016b). “México, el país con más periodistas desaparecidos; 23 casos en doce años”, 9 de febrero. Recuperado de http://articulo19.org/mexico-el-pais-con-mas-periodistas-desaparecidos-23-caso-en-doce-anos/, consultado el 22 de octubre de 2016.

Badie, Bertrand (2016). “Introduction. Guerres d’hier et d’aujourd’hui”, en Bertrand Badie y Dominique Vidal (coord.). Nouvelles guerres. Comprendre les conflits du XXIème siècle. París: Editions La Découverte, pp 11-25.

CNDH (2013) Recomendación 20 sobre agravios a periodistas en México y la impunidad imperante. Recuperado de http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5310858&fecha=19/08/2013, consultado el 27 de enero de 2017.

Correa-Cabrera, Guadalupe (2014). “Violence, Paramilitarization and Hydrocarbons: A Business Model of Organized Crime in the State of Tamaulipas, Mexico”, ponencia presentada en el Congreso del LASA, 21-24 de mayo de 2014, Chicago.

De León, Salvador (2012). Comunicación pública y transición política. Aguascalientes: Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes.

Del Palacio, Celia (2015). “Periodismo impreso, poderes y violencia en Veracruz 2010-2014. Estrategias de control de la información”, Comunicación y Sociedad, núm. 24, julio/diciembre, pp. 19-46. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/comso/n24/n24a2.pdf, consultado el 20 de enero de 2017.

Documentemos los agravios (2010). “Presuntos miembros del crimen organizado secuestraron y liberaron torturados a dos periodistas en Tamaulipas”, 4 de marzo. Recuperado de http://losagravios.blogspot.fr/2010_03_01_archive.html, consultado el 24 de enero de 2017.

Eiss, Paul K. (2014). “The narcomedia. A reader’s guide”, Latin American Perspectives, Issue 195, vol. 41, núm. 2, marzo, pp. 78-98.

Flores, Carlos (2013). Historias de polvo y sangre. Génesis y evolución del tráfico de drogas en el estado de Tamaulipas. México: CIESAS.

Freedom House (2017). “Nosotros. Protección de derechos humanos y libertad de expresión Freedom House México”. Recuperado de https://freedomhouse.org/nosotros, consultado el 30 de julio de 2017.

Gibler, John (2015). Mourir au Mexique. Narcotraffic et terreur d’Etat. Toulouse: Collectif des Métiers de l’Edition.

Kaldor, Mary (2001). Las nuevas guerras. Violencia organizada en la era de la global. Barcelona: Tusquets.

López, Martha Olivia (2015). Tamaulipas: La construcción del silencio, Freedom House. Recuperado de https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/Tamaulipas-La%20construccio%C3%ACn%20del%20silencio.pdf, consultado el 1 de febrero de 2017.

López de la Roche, Fabio (2009). Conflicto, hegemonía y nacionalismo tutelado en Colombia 2002-2008: Entre la comunicación gubernamental y la ficción noticiosa de televisión (Disertación doctoral), University of Pittsburgh. Recuperado de http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/7572/, consultado el 21 de mayo de 2018.

McSwann, Angus (1999). “Guerra, globalización y manipulación”. Chasqui, núm. 65. Recuperado de http://www.revistachasqui.org/index.php/chasqui/article/view/1259/1288, consultado el 21 de mayo de 2018.

Nava, José Carlos (2014). Desde la agresión centrada en el reportero al atentado corporativo-organizacional: el caso de la Comarca Lagunera en Coahuila y Durango. Reporte de Investigación Cualitativa, Maestría en Periodismo y Asuntos Públicos. México: CIDE.

Observatorio de la libertad de prensa en Latinoamérica (2016). “México. Periodistas muertos y asesinados”. Recuperado de http://www.infoamerica.org/libex/muertes/atentados_mx.htm, consultado el 13 de enero de 2017.

Reguillo, Rosana (2000). “Los laberintos del miedo. Un recorrido para fin de siglo”, Revista de Estudios Sociales, núm. 5. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81500507, consultado el 25 de octubre de 2016.

Reporteros sin Fronteras (2016). “Clasificación mundial 2016. Análisis. América: Periodismo a punta de fusil y a golpes de porra”, 20 de abril. Recuperado de http://www.rsf-es.org/news/clasificacion-mundial-2016-analisis-america/, consultado el 22 de octubre de 2016.

Romero Puga, Juan Carlos (2015). “Los años que le robaron al periodismo”, Letras Libres Núm. 193, 8 de enero. Recuperado de http://www.letraslibres.com/mexico-espana/politica/los-anos-que-le-robaron-al-periodismo, consultado el 24 de enero de 2017.

Torres, Karla (2012). Los impactos de la violencia en el trabajo de los periodistas que cubren Nuevo León. Antes y después del 2006 (Tesis de maestría), EGAP/Tec de Monterrey.

Valdés, Guillermo (2013). “El nacimiento de un ejército criminal”. Nexos, 1 de septiembre. Recuperado de http://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=15460, consultado el 9 de diciembre de 2016.

Wall Street Journal (2012). Mary Anastasia O’Grady, “La prensa mexicana bajo fuego”, 27 de agosto. Recuperado de http://lat.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390444914904577613983632311446, consultado el 9 de diciembre de 2016.

Wikileaks (2009). Cable de Bruce Williamson, Consul General de Monterrey, 27 de julio. Recuperado de https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09MONTERREY284_a.html, consultado el 24 de enero de 2017.