Flexible capitalism: biographical diagrams and suicide in Quintana Roo

- Eliana Cardenas Mendez

- ― see biodata

Flexible capitalism: biographical diagrams and suicide in Quintana Roo

Receipt: July 31, 2024

Acceptance: February 17, 2025

Abstract

This paper presents the impact of the development of the corporate tourism industry on the biographical diagrams of workers and its relationship with the high rates of suicide in Quintana Roo. With a qualitative methodology, it presents the phenomenon of suicide as a modality of social violence, which stems from a political rationality that is expressed in the abandonment and neglect of people by the national States. People, unable to solve structural problems in the personal sphere, decree the end of their lives by their own hand; suicide lodged in the plane of individual life leaves hidden the dynamics of power and the form of degradation of the subject from their own subjective intimacy.

Keywords: flexible capital, biographical diagrams, suicide, career paths, tourism, social violence

flexible capitalism: life courses and suicide in quintana roo

This article examines the impact of the corporate tourism industry on workers' life courses, focusing on how the industry's development relates to the high suicide rates in Quintana Roo. Drawing on a qualitative methodology, it frames suicide as a form of social violence perpetrated by nation-states that abandon and neglect individuals as part of their political rationale. Unable to resolve structural problems in their personal lives, many workers ultimately decide to take their own lives. Within the individual life course, suicide reveals power dynamics and the subjective experience of personal unraveling.

Keywords: suicide, tourism, life courses, social violence, career trajectories, flexible capitalism.

Introduction

The complex process experienced by the state of Quintana Roo since its foundation in 1974 as one of the last entities of the Mexican federation, to become one of the most important tourist poles in Mexico, is reflected in multiple problems of economic, environmental, social violence and psychosocial problems affecting the entity. Suicide in the state of Quintana Roo has been an issue of growing concern due to the magnitude and frequency with which it has manifested itself since the late nineties of the last century, with a notable increase in the course of the post-pandemic of covid-19 (Montañez, 2020; Ramirez, 2022).

According to data presented in 1996 on the epidemiology of suicide in Mexico during the period from 1970 to 1994, the following is stated

In 1970 there were 554 deaths by suicide in the entire Mexican Republic, for both sexes, and 2,603 in 1994. During this period the suicide rate in both sexes went from 1.13 per 100 000 inhabitants in 1970 to 2.89 per 100 000 inhabitants in 1994, that is, there was an increase of 156% (Rosovsky, Borges, Gómez C. and Gutiérrez, 2010).

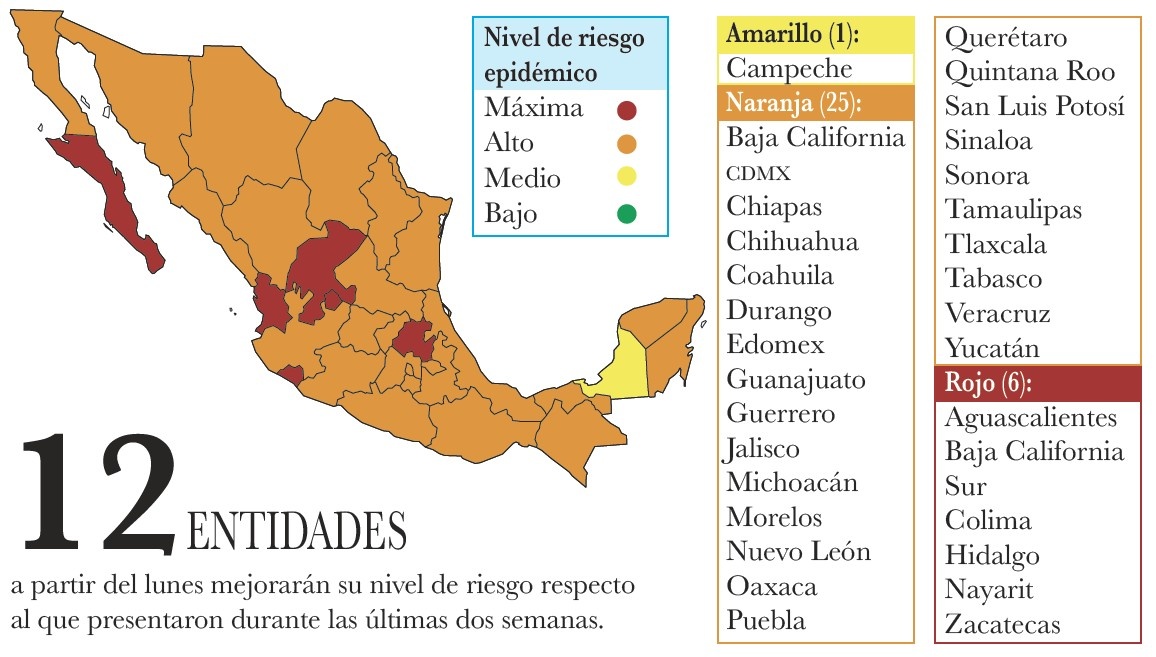

According to suicide mortality rates by state in Mexico, Quintana Roo was in ninth place in 1990, and in 2007 it rose to first place nationally. The problem has maintained a variable intensity, but always within the first places. With the covid-19 pandemic, the number of suicides increased at the national level; according to figures from the inegi 8,447 completed suicides were observed, 1,224 more than in 2019 (imss2022); that is, a rate of 6.2 per 100,000 population. In the state, the impact of the pandemic was reflected in the increase in registered events, which rose from 135 in 2019 to 209 in 2020 (inegi, 2020).

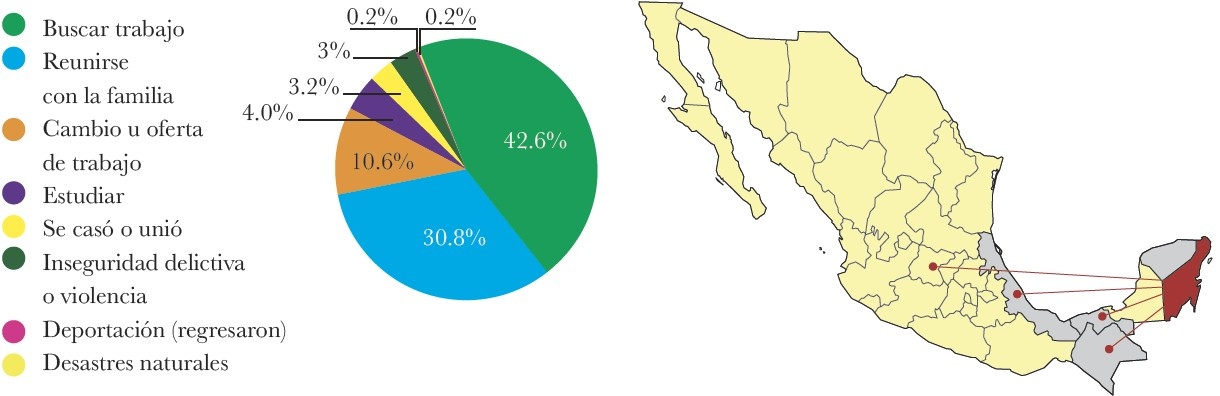

The municipality of Benito Juarez, with Cancun at the forefront, has been the entity with the highest number of reported suicides, less than 30 years after that city became one of the most important tourist destinations in the world and a pole of great migratory attraction, both nationally and internationally. However, during the pandemic, a high peak of suicides was registered in the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, in the south of the state, a region dedicated to primary economic activities and with an incipient tourist development. The deaths occurred specifically in Chetumal, the state capital, which has become a destination for migrants seeking employment in the tourism sector, especially in the municipality of Bacalar. In sum, the post-pandemic has pointed to the municipalities of Benito Juárez, Solidaridad and Othón P. Blanco as the areas with the highest incidence of suicide deaths.

The reasons behind this phenomenon are complex and multifactorial. The effort to explain it is based on three argumentative axes, which are expressed in journalistic articles and academic dissertations, and are summarized as follows: 1. sociological; 2. the hegemonic medical model; and 3. the culturalist approach. The first explains suicide as a result of states of social anomie, absence of social control systems and excessive individualism; from this perspective the central argument holds that people commit suicide because of inequalities between tourist ostentation and poverty in the regions. The second explanation of the phenomenon refers to endogenous causes, such as personality disorders that manifest themselves in a wide range of symptoms: depressive states, anxiety, bipolarity. Therefore, suicide is considered an act committed by subjects with morbid personalities. In the third reasoning, suicide is consubstantial to culture; it is part of the cosmovision of the Mayan peoples of the Yucatan peninsula.1 The limitations of these lines of explanation lie in the fact that they situate the problem on the individual level and in material poverty, in addition to contributing to the exoticization of Mayan culture, presenting it as alien to contemporary times. In this way, they fail to notice the onslaught of the neoliberal model on ancestral and community organizational forms.

The objectives of this work are the following: 1. To identify in the biographical narratives the work trajectories in various labor fields and 2. To recognize the impact of the neoliberal model in Quintana Roo through the concept of individualization, understood as the personal distribution of structurally generated inequalities. The process of individualization produces biographical diagrams that allow us to analyze trends, identify biographical patterns and understand the impact of neoliberalism in the configuration of biographical trajectories and models characterized by uncertainty, feelings of failure and emptying of vital meaning.

Hypothesis

Suicide is a form of social violence that stems from a political rationality expressed in the abandonment and neglect of people by national States, which forces people to try to solve structural problems at the level of their personal lives; when this fails, people decree the end of their lives by their own hand. The study of suicide in the biographical plane, the result of failed relationships and systematic personal failures, conceals the dynamics of power and the impact on peoples and individuals, while contributing to the naturalization and normalization of the sacrificial meaning of suicide.

Critical path

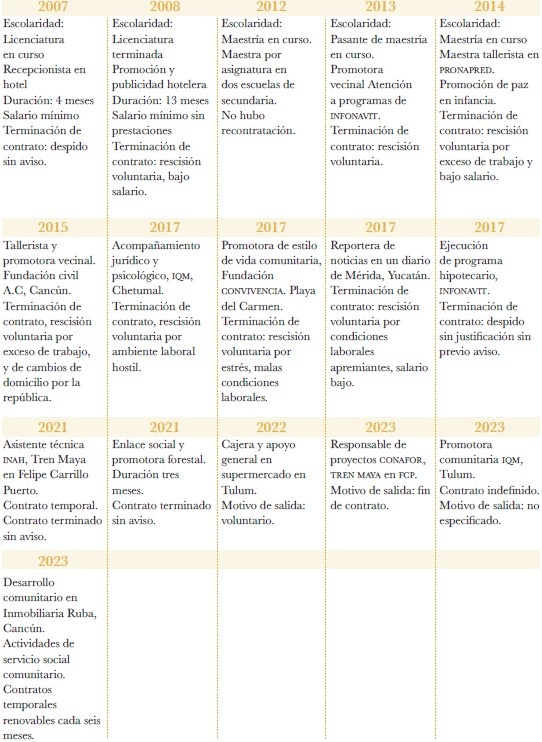

Through qualitative research -focused on the subjective experiences and meanings of people- in-depth interviews were conducted without social or gender distinctions and their life histories were reconstructed. From these stories, behavioral patterns and common meanings were identified, which were visualized through biographical diagrams, i.e., diagrams that show the significant moments in a person's life, linked to their work trajectories.

The use of analytical techniques such as data coding, organization and classification made it possible to construct these biographical diagrams based on labor trajectories. Likewise, the hermeneutic approach facilitated the understanding of the meaning of the experience of unemployment and precariousness in people belonging to different social sectors.

In this sense, it is argued that the dominant economic model -particularly with regard to corporate tourism, precarious forms of employment and labor flexibilization regimes- produces structural conditions that generate persistent experiences of exclusion, devaluation and social residuality. These experiences not only affect the material dimensions of life, but also have a profound impact on subjectivity, eroding self-esteem, emotional stability and individuals' sense of belonging. Several studies have pointed out that this intimate attrition, linked to job instability and the absence of future horizons, constitutes a significant risk factor in the increase of suicides in regions marked by unequal tourist economies (Berardi, 2012; Standing, 2011; Butler, 2004).

I. Quintana Roo, tourism and flexible labor

Tourism is considered one of the main drivers of global development. The generation of employment is highlighted as its main attribute; according to the Consolidated Report of the Tourism Promotion Council2 In 2018, 8.6% of total employment in Mexico was generated by the tourism sector. Tourism represents the third largest source of foreign exchange for Mexico, behind only oil revenues and remittances sent by migrants living in the United States. In 2017, tourism contributed 8.7% to the country's gross domestic product and generated 3.7 million direct jobs (Datatur, 2018).

Tourism is the articulating axis of economic activities in Quintana Roo, and has progressively become one of the main tourist destinations in the country and Latin America. Figures from the State Secretariat of Tourism (sedetur, 2023) indicate that a total of 1,877,546 tourists visited the different destinations of Quintana Roo, while in the year 2022 there were 1,806,834, which means that in the summer of 2023 the goal was surpassed, with an increase of 3.9 % and an economic spill of more than 19 billion dollars was generated.3

However, the boom of this economic dynamic contrasts with the labor conditions of workers and the high levels of suicide in the state. It should be noted that tourism is perhaps one of the labor dynamics that most vigorously reveals the character of "flexible capitalism". Flexible capitalism, polyvalence and labor flexibility, as well as the tertiarization of employment, are terms associated with the modernization process focused on dynamizing production and strengthening the economy. Modernization, however, has as its central objective the profitability of capital over the labor force through a more flexible use by means of the personalization of relations between companies and workers; these measures have contributed to unemployment, intermittent employment and labor precariousness. On the other hand, wages in this scheme are also flexible, as they are considered a cost that affects the profitability of companies, and are divided between basic or minimum monetary retributions and payments in kind, gasoline bonuses, punctuality bonuses or tips, drastically affecting the workers' economy.

The implementation of this model disrupted collective work practices in Quintana Roo, previously linked to agriculture, fishing and manufacturing, economic dynamics anchored in community social relations, and has generated processes of individualization in the sense proposed by Ulrich Beck (1998). Individualization, for this author, refers to the individual distribution of systemically generated inequalities. The weakening of the State in its substantive functions to provide citizens with the conditions and mechanisms to guarantee social reproduction and existence has forced people to try to solve structural problems at the biographical level and to assume responsibility for the consequences and risks derived from processes beyond their control (Beck, 1998, 2003).

The impact of this model on employment or the precariousness of employment is clearly revealed in biographical patterns marked by uncertainty, uneasiness and hopelessness; in other words, flexible capitalism has shaped subjectivities that emphasize personal willpower and a positive attitude as the only resource available to alleviate the adversities of labor precariousness, whose instability and pay do not allow for long-term life planning. Flexible work, as Richard Sennett (2015) states, prevents the construction of a stable and lasting biographical narrative. On the contrary, biographical trajectories are fragmented into employment segments and an occupational heterogeneity that generates subsequent negative psychological burdens.

II. Working conditions and salaries

These figures demonstrate the continuous growth and strength of Quintana Roo as a leading tourist destination worldwide and the reason why it is considered one of the capital axes of the national economy. In this context, it is also a center of migratory attraction of expelled populations, both from urban and rural areas; these are populations that come to the state in search of employment and better living conditions, especially to cities such as Cancun, Playa del Carmen and Tulum.

Although tourism is currently one of the fastest growing activities worldwide, its regional distribution has not been homogeneous; there is greater acceleration in dependent economies, where it reproduces a condition of international subordination, since it is a function of the foreign market. It should also be taken into account that foreign capital directs this activity and makes possible a set of seasonal, casual and intensive tasks carried out by unskilled labor. Therefore, the economic boom revealed by tourism is not reflected in the improvement of the living conditions of the inhabitants who work in this industry -hotels, tour operators, tour guides, commerce, restaurants-, who are hired under precarious conditions, with deregulated contracts, without labor guarantees and with wages below the minimum wage, an income that workers must supplement with tips or commissions for working more than eight hours a day.

In this sense, it is possible to affirm that it is due to the working conditions of the population inserted in the tourism sector that this industry without chimneys can report unparalleled economic growth indicators.4 Tourism in its mode of flexible capitalism "describes a system in which workers are asked to be agile; they are also asked to be open to change, to take one risk after another, to depend less and less on formal regulations and procedures" (Sennet, 2015). The worker of flexible capitalism is not required patience to climb the ladder in the rigid and hierarchical industry, but permanent change, transience, innovation, short-term projects and mobility without limits, without guarantee or job stability.

Although the labor conditions of people working in the tourism industry have been indicated, this dynamic is not exclusive to this sector, but affects all workers in associated institutional and economic areas, such as construction, land and water transportation, supermarkets, commerce in general, and tourism agencies. This situation is reflected in job instability and mobility between different sectors, so that a worker, even with a high qualification, in an average age range of 18 to 35 years, can change jobs up to eleven times in search of better wages, greater job security and less intense working hours. Wages are distributed in the form of daily cash payments, bonuses, allowances, housing, bonuses, commissions and benefits in kind, such as bonuses or other compensation given to the worker for his or her work.

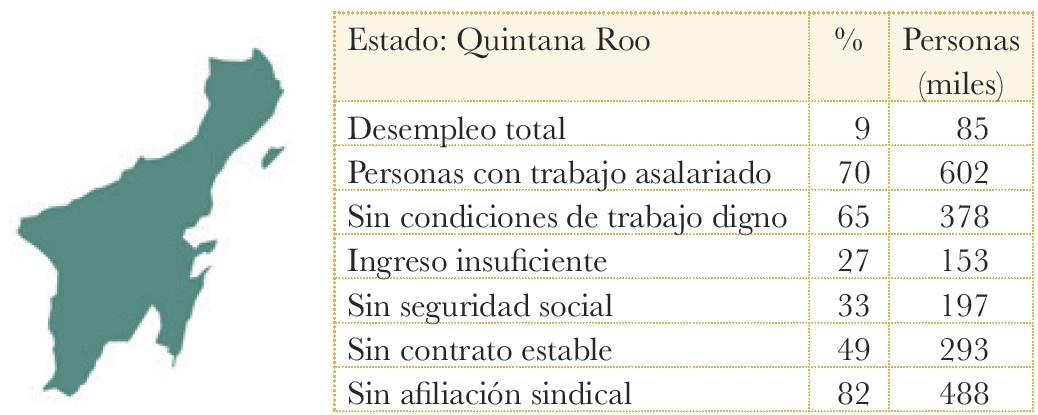

Quintana Roo has 811,000 employed people, that is, people who have a job; however, according to the Semáforo de Trabajo Digno of the organization Acción Ciudadana Frente a la Pobreza (Citizen Action Against Poverty), workers are working in precarious labor conditions:

The new study, the most recent during this period of pandemic, reveals that of the total number of people who work, only 181,000 do so formally and earn enough to cover their expenses. In contrast, some 607,000 people work without any kind of social security, and the income they earn is not even enough to feed a family.5

In these circumstances there is a high percentage of the population that cannot afford to buy the basic food basket with their salary and work without any type of social security, therefore, with these indicators it is considered a precarious labor condition. For the organization, the situation could worsen and reach unemployment rates in the entity of up to 15.7%, in addition to the fact that 103,000 are currently underemployed. For practical purposes, however, the acquisition of tips becomes one of the main attractions of tourism, because it allows those who work providing services to tourists to have direct access to foreign currency in these destinations of international consumption and, thus, that these flow to the interior of the tourist cities.

However, because employment in this sector is subordinated to tipping, it is highly dependent on tourism productivity and is therefore highly vulnerable to crises. As a result, as long as there is a high influx of tourists, workers in tourist cities can earn good incomes. However, when tourism demand decreases, a large number of workers become unemployed and face high levels of uncertainty. This situation places the majority of workers in marginal conditions, not only because of their low income, but also because of the social exclusion that comes with lack of access to consumption and better opportunities.

In this regard, it is important to note that unemployment, poor working conditions, along with family and legal losses are, according to interviews and newspaper archives, the main motives that drive people to suicide; therefore, the most prone people are in the age group between 20 and 40 years old.6 Between 2019 and 2023, the increase in suicides occurred in low- and middle-income countries; in that same period, in Quintana Roo, suicide increased in Cancun and Chetumal, the tourist and administrative capitals of this state.7

III. Flexible capitalism and biographical diagrams

It is commonplace to say that life histories are the version that a narrator or subject questioned in his or her own story refers to the researcher. However, it is necessary to reaffirm that life histories are a qualitative research strategy that pursues not the story of a subject in itself, but has as its main objective to identify in a person's life story the way in which structural problems are embodied and, at the same time, the way in which certain social problems shape life stories. In this way, the stories or biographical segments chosen for this work are not drifting experiences or chronicles of events, they are the narrative sequence in which the sociability that constitutes a biographical trajectory is inscribed; each of the stories collected in this research refers to the impact and shock, the oppression that flexible capitalism exerts on the material and psychic experience of people.

The contents referred to in the different biographical segments speak to us, in their diversity, of a pattern: a weft of meaning and common meanings, traversed by flexible capitalism characterized by uncertainty, short term, constant anxiety in the face of crisis and the permanent risk of inexorable decisions. These stories highlight the impossibility, for many people, of constructing a stable and sequential biographical trajectory over time within this economic model. On the contrary, these life stories show fragments of work or occupational experiences that are reflected in acute symptoms that compromise the emotional stability of those who live them.

With these premises, we understand a biographical diagram as a map dramatically constructed from labor trajectories marked by precariousness. This has generated a pattern whose main characteristic is its psychological impact and the way in which it compromises the vital meaning of the subjects, who are forced to constantly remake and repair themselves in order to make their own existence possible.

I manage, but there are days....

I am from Veracruz, I have a major in business administration; first I worked in Cancun in a travel agency and then as a tour operator for the promotion of the Mayan world, then I joined tour guides and learned a lot, but those jobs are seasonal and there is no security, no stable contracts, then I went to Cozumel and sold online hotel vacation promotions, now I also work with a real estate agency and sell houses, land; I have to do many things to live here; I do not know what I will do, I have no stable job, everything is on commission. I always manage, but there are days when I don't know what to do.

See you on days off

We are from Kantunilkín and my wife and I work in Holbox in different hotels; we are waiters mostly, but if service is needed in the bar, kitchen, garden, we have to be on call; they give us our food and lodging which are collective rooms, we share with people from many parts who do different trades in the hotel; the days are long, and we cannot go out; my wife and I see each other on our day off in Kantunilkín, there we see the children who stay with my mother-in-law all week; it is difficult to have a life as a couple or a family life; when the season is off we do have time, but we do not have money.

With this uncertainty, I do not even think about

On June 20, 2023, I received via WhatsApp this message: "Good morning, Viviana, bad news, they inform me that there is a cut of digit (sic) 7 and it was your turn. I advance you to be aware of your mail, the notification will arrive there"; he signed with a very unpleasant sticker: an old man wiping his tears with a handkerchief.

Ten days later, signed by the human resources manager of the conaforI received the official letter; the heading read C. Viviana Salgado, with no curricular distinctions, nothing. There I was officially informed of the termination of my appointment as Enlace de Promotoría Social at the Felipe Carrillo Puerto office. The reason for the dismissal was that my three-month permanent appointment had expired. They thanked me and communicated that we would be in contact for future selection processes. I was very angry because I was not notified in time, I felt thrown into the void and hanging by a thread. I started to look for a job immediately, I could not be unemployed, I had to pay rent, food, nobody supports me and luckily I do not have children. That's how I started working as a cashier at the "super Aki". I was there for six months until another call came up in Cancun, I applied and they accepted me. The work I do is more in line with my level of studies and my experience, although the contracts are temporary, depending on your performance you can last up to three years, but with renewable contracts every three or six months. Most of the employees, there are eleven of us, come from other parts of the country, I am the only one from Quintana Roo. I don't plan to have children, I am already 35 years old; with this uncertainty I don't even think about it.

It's dirty, one feels denigrated.

I am from Toluca, I am 26 years old, a marketer with a master's degree in digital media and I have dedicated myself to digital marketing in these years; I work in a motorcycle agency that is in Campeche, Chetumal and Yucatan. The company is a dealership, the motorcycles are produced in India and the company is owned by a Mexican entrepreneur; the dealership is independent, it is only authorized by the manufacturer brand to sell the motorcycles here, through a concession contract. Although there were previous experiences in the Peninsula with this brand, the current success of this company has to do with the distribution and advertising in the networks, which is the work I do. I do not have a contract or benefits, although I have been working with them for four years, but I am not under any regime, I am not paid by payroll, but rather by deposits in oxxo or transfers from different companies, because my bosses use this method so as not to generate taxes or have problems with the tax authorities. satMy salary is $ 6 000 pesos per month, but I manage other social networks and I complete a salary of 9 or 10 000 pesos per month. I work at home from 9 am to 5 pm and on Saturday from 9 am to 2 pm. Under these same conditions we work 146 employees in the three states of the Peninsula; the salesmen are paid on commission and the mechanics are paid on commission for service and sale of automotive products. This way of making money seems very dirty to me, because we know how people work in India and the way they exploit us seems very dirty to me, one feels denigrated. Anyway, I have no loyalty with them, when I leave there, I also take all the information I have, that's what they risk, there are pages that I created in fb They cannot take them away from me because I have the passwords; I have everything digital with which they make clients; just from one branch, with the work I do, they get 500 or 600 clients a month. I have had to attend, on a Monday, about 800 clients from a single page, they would also lose, temporarily, but they lose.

With the salary I have I can't pay rent because I pay $4300 a month and I would only have $5 700 left for everything else, food, utilities. But I live with my partner who is a computer technician, works in the same company as a salesman and is paid by commission. The salary is enough for us because we live in Chetumal, in the cdmx or in Toluca, where I am from, we would not be able to live on that salary. No, we cannot make plans, draw up a biographical project, because that means long term; if it were not for the fact that I am very restless and I am looking for what other things I can do, we could not even live in the present, let alone plan for the long term, let alone with quality of life. It is not about changing jobs, because all companies are paying the same. If I want to earn more, I have to work more, for that I have to work with several social reasons, under the same regime, without contracts, but at the same time, I divide my time to work with several companies. When I ask for a raise, the bosses of the different companies pass the buck, so tell the others you work with to pay you more, the only way out is to get other employers to be able to get a salary without hardship, but I get exhausted [...] Yes, of course, this condition affects my mood, there is a lot of uncertainty, not knowing what is going to happen to you and that affects your mental health. I have taken therapy and it has helped me a lot to contain myself, because I have wanted to throw the job at them and tell them so far, but therapy has helped me, and I tell myself, calm down, you can't do that, you also have to eat. My husband is more affected than I am, several times a week he is very agitated and says to me: "What do I do now, what if this happens, what if we can't make ends meet?" And when he doesn't sell he gets depressed, he just calms down longing to recover the following week. The uncertainty and the mental state generated by the precariousness of work is complicated, he is more anxious and anxiety can generate terrible ideas.

I have tried three ventures with friends, scented candles, printed T-shirts, chewing gum, but it has not worked, it is very difficult to start a business, you run many risks.

Work, more than just a means to obtain resources and earn a living, also represents a guarantee of stability and development for people, according to Sennett, "human beings manage to be at peace with themselves [...] work is the only way in which life becomes bearable; that is, to the extent that people come to master the routine and its rhythms people come to master their work and become calm at the same time" (Sennett, 2015: 35).

This presentation by Sennett alerts us to the difference between work and employment: the first as an exercise and a group of activities that have a result, whose product is the mastery of time; it is through work that life has meaning, allows personal fulfillment and its historical meaning with others, being useful to society; employment, on the other hand, refers to activities that are executed in exchange for a salary, and people do not necessarily perform in these tasks; However, beyond the differentiation between the two concepts, what is certain is that neoliberal capitalism, polyvalence and labor flexibility subtract the possibility of personal fulfillment as they force people to travel from job to job with a view to earning a salary to guarantee survival; in this way social commitment is clearly affected, society does not have it with people and people do not have it with anyone. The situation is much more critical if people are unemployed or if their chances of finding employment are prolonged over time. Unemployment, in the past, as Zygmunt Bauman (2003) points out, drew its semantic load from a society that was obliged to guarantee people the means and security to earn a living. However, unemployment has become something permanent, unemployment threatens the meaning of living; for Anthony Giddens, to imagine a life made of momentary impulses, without habits, without routines is a meaningless existence.8 This is how flexible capitalism has produced new power structures that instead of creating conditions for the liberalization of people have made them dependent, always at the limit of their own circumstances.

In other words, the conditions imposed by the neoliberal model, or flexible capital, daily weave a web of plots, multiple faces of social violence that is revealed at the individual level in feelings of uncertainty, humiliation, anguish, depression and feelings of defeat that bring with them a progressive emptying of the meaning of life. It should be pointed out that the discomforts identifiable in the life histories of the population consulted in Quintana Roo constitute a concrete manifestation of the new social order, which, by directly affecting labor conditions -a fundamental right on which others such as health, housing, survival and, in broader terms, social existence depend-, has institutionalized uncertainty and shifted the responsibility for solving structural problems to the individual sphere.

The impossibility inherent in this demand produces in the subjects a persistent sense of failure. Unable to respond to these demands, people generate renewed forms of self-blame. It is in this context that feelings of residualityThe increase in suicides is closely linked to the increase in suicides registered in the entity (see Table 1).

Conclusions

Suicide is a multifactorial phenomenon, however, the approaches to its study in the state of Quintana Roo reveal the supremacy of the hegemonic medical approach that starts from the psychosomatic symptoms that afflict the individual prior to the personal decision to end one's own life by personal decision.

The result of this research proceeds in the opposite way: although suicide is an individual act, it constitutes one of the forms in which social violence is expressed. It is, above all, the fatal outcome of a chain of adverse structural events that affect individuals. Therefore, the central question is oriented towards the social and structural conditions in which people live.

From this perspective, the high suicide rates in the state of Quintana Roo, as exposed in this research, are linked to the development of the corporate tourism industry. This sector, as is well known, represents one of the most dynamic branches of the global economy and, at the same time, functions as a neocolonial instrument that perpetuates inequalities and maintains the status of domination over developing countries.

The impacts of this model are reflected not only in the transformations in the use of space, the modification of productive activities or the dispossession of cultural assets, but also in the precariousness of employment, characterized by its instability, unpredictable adjustments and permanent layoffs. Thus, unemployment ceases to be a transitory condition - as the semantics of the term suggests - and becomes a chronic phenomenon that generates a series of biographies of riskThe situation is marked by the constant threat to the future and the probability of permanent losses and damages, both material, psychological and cultural.

The impact on employment in the context of flexible capitalism and the new forms of appropriation of the labor force are related to the generation of new subjective profiles marked by situations of precariousness, risk and uncertainty. From this perspective, it can be understood that, at the basis of the high suicide rates in the state, there is an interrelation between structural transformations and the devastating impact on people, not only on the material level that affects biological reproduction, but also on their own individual self-perception.

The methodological effort to link labor trajectories and biographical patterns reveals that the flexible work system forces people to move through various fields in permanent change, which is a source of anxiety and risk, while at the same time revealing the urgency in which people find themselves in order to draw up lasting and stable biographical projects.

With the implementation of the neoliberal model and privatization processes in the three regions of the state, forms of collective and community production were dismantled, as well as union organizational structures, such as fishermen's cooperatives, lumber or peasant associations and ejidos. The organizational structure of extended families, which had previously served as a buffer in the face of adversity, was also weakened. This gave way to processes of individualization in the sense proposed by Beck (2003), in which systemic transformations and failures do not exclusively affect a social sector or a class, but individuals directly.

Individualization, in other terms, implies that people are thrown into the struggle for survival without safety nets, confronting them with the need to self-produce their lives in a continuous present. Anxiety in the face of unemployment, as argued following Sennett (2015), is deeply intertwined with the dynamics of the new capitalism. This apprehension in the face of work has eroded people's self-perception and self-consciousness, weakened the self-worth of families, fragmented communities, and altered the significance of work, which used to be linked both to personal history and to the individual conceived as a fundamental piece within social history.

The transfer of structural problems to the individual level revealed in the biographical diagrams presented here begins with labor trajectories at an early age with university degrees and that, due to the dismantling of the right to a secure job, individuals are forced into constant labor temporariness and uncertainty; These structural transformations have material and psychological repercussions, which bring with them feelings of failure of various orders in the personal life and promote new forms of self-blame, feelings of needlessness that erode the subject from his or her own intimacy and compromise the meaning of life.

In short, it is necessary to advance in the understanding of the social basis of suicide to the extent that it is a priority to recognize, in the massification of unemployment and the disarticulation of the social fabric, the dynamics of a system that has managed to generate enormous quantities of unnecessary and dispensable populations; at the basis of suicide it is necessary to recognize a system that has managed to undermine human dignity from its own subjective intimacy, through the individual distribution of inequalities.

Bibliography

Bauman, Zygmunt (2003). Vidas desperdiciadas, la modernidad y sus parias. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Berardi, Franco (2012). La fábrica de la infelicidad: nuevas formas de trabajo y movimiento global. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños.

Beck, Ulrich (1998). La sociedad del riesgo. Hacia una nueva modernidad. Barcelona: Paidós. https://www.gub.uy/sistema-nacional-emergencias/sites/sistema-nacional-emergencias/files/documentos/publicaciones/La%2Bsociedad%2Bdel%2Briesgo%2Bhacia%2Buna%2Bnueva%2Bmodernidad%20-BECK.pdf

— (2003). La individualización: el individualismo institucionalizado y sus consecuencias sociales y políticas. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica. https://latam.casadellibro.com/libro-la-individualizacion-el-individualismo-institucionalizado-y-sus-consecuencias-sociales-y-politicas/9788449314704/929505

Borges, Guilherme, Ricardo Orozco, Corina Benjet y María Elena Medina-Mora (2010). “Suicidio y conductas suicidas en México: retrospectiva y situación actual”, Salud Pública de México, 52 (4), pp. 292-304.

Butler, Judith (2004). Vida precaria: el poder del duelo y la violencia. Buenos Aires/México: Paidós.

Cárdenas Méndez, Eliana (2021). La puerta falsa del paraíso. El suicidio en Quintana Roo. Chetumal: Universidad de Quintana Roo.

Consejo de Promoción Turística de México (2018). Informe consolidado de actividades 2018. Ciudad de México: Gobierno de México. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/415759/Informe_Consolidado_VF.pdf

Coordinación General de Comunicación (2023). “Registra zona maya Quintana Roo incremento de visitantes en vacaciones de verano”. Recuperado el 30 de noviembre de 2023. https://cgc.qroo.gob.mx/registra-zona-maya-de-quintana-roo-incremento-de-visitantes-en-vacaciones-de-verano/#:~:text=De%20acuerdo%20con%20cifras%20de,alcanzado%20un%20incremento%20de%203.9

datatur (2018). Compendio estadístico del turismo en México 2017. México: Secretaría de Turismo/Subsecretaría de Planeación y Política Turística. http://www.datatur.sectur.gob.mx/SitePages/CompendioEstadistico.aspx

Dinamismo y Estudio Frente a la Pobreza, A. C. (2021). “Presentación: Semáforo de trabajo digno sur/sureste”. Semáforo del Trabajo Digno estatal, Quintana Roo. https://frentealapobreza.mx/com-2113/

Ibarra, Alejandro (s. f.). “Cancún y Chetumal, con más suicidas en Quintana Roo; 70%, son hombres”, PorEsto! https://www.poresto.net/quintana-roo/2023/9/13/cancun-chetumal-con-mas-suicidas-en-quintana-roo-70-son-hombres-399444.html

Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (imss) (2022, 19 de septiembre). Hablemos de suicidio. México: Gobierno de México. https://www.gob.mx/imss/articulos/hablemos-de-suicidio

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (inegi) (2021). Estadísticas de suicidios en México, 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx

Montañez, José Luis (2020). “Alarmante incremento de suicidios”. Diario Imagen Quintana Roo On Line. https://diarioimagenqroo.mx/noticias/?p=178643

Ramírez, Alma (2022). “Pandemia incrementó número de suicidios en QRoo”, La Jornada Maya, 9 de septiembre. https://www.lajornadamaya.mx/quintanaroo/202774/suicidio-pandemia-incremento-numero-de-suicidios-en-quintana-roo

Diario de Chiapas (2020). “Pandemia aumenta suicidios en jóvenes”, 15 de agosto. El Diario Media Group. Recuperado de: https://diariodechiapas.com/ultima-hora/pandemia-aumenta-suicidios-en-jovenes/

Sennett, Richard (2015). La corrosión del carácter: consecuencias personales del trabajo en el nuevo capitalismo. Barcelona: Anagrama. https://www.anagrama-ed.es/libro/argumentos/la-corrosion-del-caracter/9788433905901/A_239z

Standing, G. (2011). The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. Londres: Bloomsbury Academic.

Eliana Cardenas Mendez holds a PhD in Social Anthropology, a master's degree in Psychoanalytic Theory, and a degree in Ethnology. ptcProfessor-researcher, tenured B, in the Department of Humanities and Languages at the University of Quintana Roo. Member of the National System of Researchers. Lines of generation and application of knowledge: anthropology of violence and anthropology of international migration. Visiting professor at national and international universities: El Colegio de San Luis, San Luis Potosí; unacarUniversidad Autónoma del Carmen, Campeche; cephci Peninsular Center for Humanities and Social Sciences, unam. ciesas Mexico, ciesas Peninsular, Universidad de La Habana, Cuba, Universidad de Costa Rica, Universidad del Valle, Colombia. He has done research and sabbatical stays at the Universidad del Valle, University of North Texas, usa uu. Author of books, coordinator of books and author of book chapters and articles on her lines of research. The false door to paradise. Suicide in Quintana Roo (2021) is his latest book on self-inflicted violence.