Diverse views of the cinematographic and photographic productions of the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive and the representation of native peoples.

- Karla Ballesteros

- ― see biodata

Diverse views of the cinematographic and photographic productions of the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive and the representation of native peoples.

Receipt: March 14, 2023

Acceptance: April 16, 2023

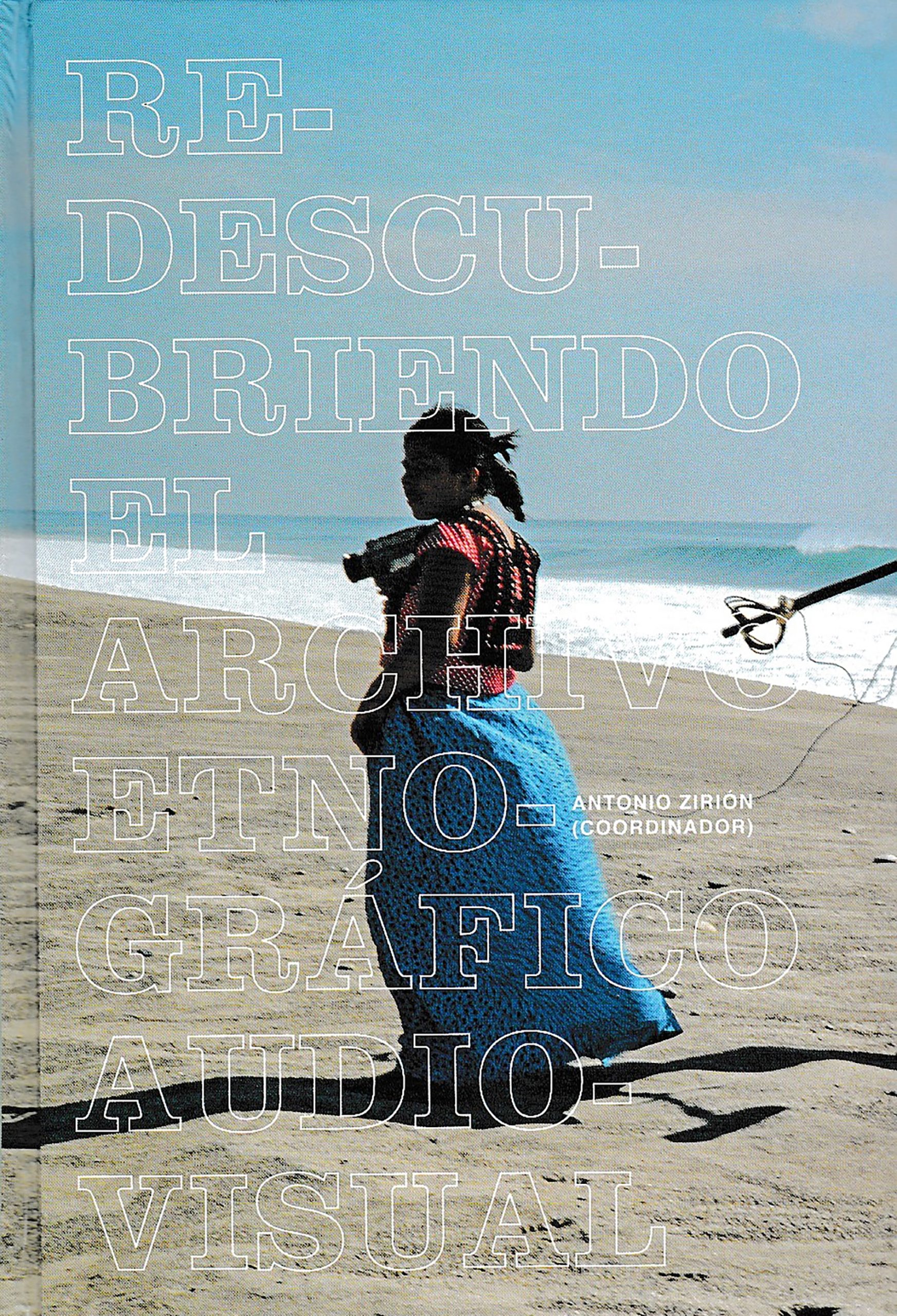

Rediscovering the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive

Antonio Zirión (coord.), 2021 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana/Elefanta Editorial, Mexico, 492 pp.

The main objective of this book is to combine a series of reflections on the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive (aea) of the National Indigenist Institute (ini), as well as the context in which it was created and developed as part of a visual record of the social organization and other aspects of the original peoples of Mexico. It also tells us about the different stages that this organization has gone through and its repercussions on the productions.

Although the archive has already been addressed by several authors (Becerril, 2015; Piño Sandoval, 2013; Rovirosa, 1992), this book is necessary because it brings into discussion issues of dispossession, marginalization, migration, loss of language, identities, just to mention some of which we continue to witness the consequences in force today. They are approached through the review of the archive's documentaries from various angles and from an interdisciplinary perspective. The great contribution is, as the title refers, "rediscovering" a foreign treasure that we seek to return through research, reflection and, above all, by making it public, that someone identifies themselves or their community, as well as their problems and contexts within each documentary. The book's coordinator's recognition of the role of women in the audiovisual record and anthropological research is relevant, which also shows stories told from them and for them.

The eight sections: substrates, otherness, spaces, divergences, memories, pedagogies, becomings and snapshots, are very suggestive words that invite us to read the thirteen chapters, and each one deals with different documentaries of the aea and also others that are not included but are closely related. In addition, the book is accompanied by a series of photographs from different archives that help us to have a broader view of the documentary production.

The first chapter, "He is God and the origin of a new ethnographic cinema in Mexico" by Álvaro Vázquez Mantecón, provides a historical context for the production of this film, which focuses on the dance of the concheros, the processions and religious cults that converged in the then Federal District in the middle of the 20th century. xxand of which we can still find samples in our days in the city and even outside the country. In the text there are a series of reflections on the narrative style of the documentary and its importance within the Mexican audiovisual production, as well as its close relationship with the way of doing anthropology.

In the second chapter, Eduardo de la Vega talks about the trajectory of two documentary filmmakers who are extremely relevant for the aeaAlberto Cortés and Rafael Montero, both graduates of the Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos, which has played a very important role with respect to the archive, since several of its graduates began their film work there, with new forms of representation and understanding of documentaries, as well as a professionalization of productions. The review of their trajectory is relevant since they offered a critical look at documentary filmmaking in the aea and his time there was decisive for his later works, turning the archive into a space of realization and reflection on the "indigenous" world and its representations; in this case, as part of an auteur cinema.

In the chapter entitled "Imaginarios cinematográficos de los pueblos rarámuri en la segunda mitad del siglo xx"Adriana Estrada presents a historical tour of the representations of the Rarámuri people, emphasizing their portraits through film with experiences that dialogue with other artistic and academic representations related to the northwestern region. The first testimonies are by Joseph Neuman in Stories of the rebellions in the Sierra Tarahumara 1626-1724also addresses the photographic and ethnographic work of Car Lumholtz and Rudolf Zabel, as well as the work of Robert Zingg.

The movie Tarahumara (1965) by Luis Alcoriza is important in Mexican cinema as a social critique that for the first time questions the nation-state relationship through the figure of a young worker of the ini and the native peoples, in this case the Tarahumara people. Sukiki (1976), by François Lartigue and Alfonso Muñoz, tells the story of overexploitation in the Sierra Tarahumara with a particular documentary style. On the other hand, Raramuri Ra´Itsaara (1983) y Teshuinada (1979) have different intentions within the framework of the same indigenism. Similarly, the author has a relevant reflection, as she wonders what the image of the Rarámuris made by them would be like, which would be interesting to investigate in the current context, since, with greater access to electronic devices, perhaps a self-representation has been generated.

"Children's shelters in the audiovisual discourse of the. ini" is the chapter written by Alejandra Jablonska, who seeks to analyze the role of the school shelters that this organization installed and implemented to offer education to children from native peoples and thus integrate them into the national life of the country, with all the controversies that this entails. The author criticizes the representation of children through the analysis of the discourse and cinematographic narrative in the documentaries that had the shelters as a theme. The first film is The World Food Program in indigenous shelters directed by Ernesto Heyerdahl in 1988, and subsequently addressed Días de albergue of 1990 by Alfonso Muñoz and lastly Future generation by Alberto Becerril from 1955. Jablonska makes a very critical review of the contradictions of what is seen in the images, in the texts and what is said in the voice of the artist. off The first two documentaries, the latter being the one that actively shows this situation -through a series of interviews with the social actors of two shelters in San Pedro and San Pablo Ayutla and El Espíritu Santo Tamazulapan-. They also give an account of the major problems they faced and, above all, how overwhelmed they were by the large number of children arriving and their demands.

The chapter "Audiovisual Geographies of the Potosi Highlands" by Frances Paola Garnica seeks to explore the representations of the geography of that region in the cinema of the ini and other fiction and non-fiction films. What is most striking about this text is the methodology, which is very different from the rest, as it places the region and its space at the center. One of its findings is that for fiction films, the area has been used for the making of films of the genre westernas well as the life of haciendas and ranches. For the documentary, the desert has been recorded and approached from different angles, having as its center the wixaritari. Undoubtedly, this article leads us to the analysis of space, geography and habitation from cinema and highlights the ability of the latter to generate crossings between space and time.

The author finds that the Wirikuta desert is one of the most registered, leaving out the Real de Guadalcázar protected natural area, which shows environmental degradation. It is a document and a reminder that the territories of the peoples wixarikas The Caravan of Dignity and Wixárika Conscience carried out a walk in May 2022 to demand the return of more than 11,000 hectares; they arrived at the zocalo of Mexico City after traveling more than 900 kilometers for 32 days to demand the restitution of their lands and to demand an audience with the president (Contreras, 2022).

In the Divergences section, the first chapter is written by Martha Urbina and is entitled "Laguna de dos tiempos", testimony of a forced modernity, a counterpart of the 1982 documentary by Eduardo Maldonado Soto. This documentary was a co-production of ini and the Cine Testimonio group and had a critical and denouncing approach to the oil development plan in Minatitlán, Veracruz, implemented by the federal government. It is relevant because it recorded the process of marginalization of the Nahua and Popoluca communities.

The author offers an analysis of the filmography of the Cine Testimonio group, which highlights its criticism and denunciation of the developmentalism and dispossession of peasant communities and native peoples in Mexico, through direct and testimonial cinema, as well as a historical, economic and social context of the country and the region. Likewise, he tells us about the making of Two-stroke lagoonThe anthropologist Victoria Novelo participated in the project, so the anthropological work was present and a much more empathetic look was achieved, according to the author.

Claudia Arroyo Quiroz writes the chapter entitled "Between ethnography, history and politics".. Luis Mandoki's team's documentaries on the Mazatecs reflect on the historical development of the Mazatec people. iniThe institution's colonialist actions, based on good intentions, to its criticisms within the institution, have made possible relevant actions such as the promotion of the indigenous video and the formation of the aea. Likewise, the Audiovisual Media Transfer project was a very strong step towards the search for self-representation and, later, the audiovisual work directed by filmmaker Luis Mandoki in conjunction with other filmmakers and anthropologists who produced two documentaries: El día que vienen los muertos, Mazatecos I and Papaloapan Mazatecos IIboth from 1981. These films lack a voice in offIn this film, they use Spanish subtitles to record the Mazatec language and collect the testimonies of dispossession, which is a very relevant act for the time and a political position against the dominant language, which is Spanish in our country.

The following chapter, "Generación futura: Una experiencia comunitaria 25 años después", by Alberto Becerril Montekio, has a special value, since its author was involved in the aea and tells us how the production process of this film was carried out, as well as a brief historical context from his perspective. Throughout his long journey, Alberto recognized the importance of incorporating community members in the production process, and although he directed the research, production and creation process in Generación Futura, he had previously experimented with collaborative productions. So for Alberto the process was the most important thing in this production, because he considers that it is when more information is obtained and above all when collaboration is achieved. The research was done together with Dr. Gonzalo Camacho. He also shared production and post-production with the youth collective Video Tamix, originally from Espíritu Santo Tamazulápam Mixe, with the protagonists being the ayuuk ja ay or people who speak the language of the mountain. A central part of this article, which offers us a guideline for future journeys of the archive, is that the author makes an analogy about food and images, and assures us that consuming industrially made images is just as harmful as eating processed food, so he invites us to see homemade images. Hence, he describes the different projections that the documentary had inside and outside the communities; in this sense, it represents a very circular model of the image that seems to me to be exemplary.

In the chapter "The Last Kiliwa Voices" by Eréndira Martínez confronts us with the disappearance of a language through the analysis of a documentary film. Cruz Ochurte Kiliwa from 1995-1998. The author leads us to reflect on language and its relationship with the original peoples, as well as the importance of the recording media. Through the stories of Cruz Uchurte, who presents the situation of her people before the exile, the land grabbing and the exploitation of the habitat, as well as the lack of economic resources to reclaim their properties, she brings us closer to this intimate and small northern town where the context does not seem to be very promising. Although the author recognizes that language is not the only thing that makes up a people, it is a fundamental part of their identity, which is why this documentary is part of the resistance of the Kiliwa people who seek to be reborn. The theme of the disappearance of languages in our country has also inspired other fictions, such as the film Sueño en otro idioma (2017) by Ernesto Contreras.

On the other hand, "Mirar en Clave Ikoots. Ethnographic readings of the first indigenous cinema" by Lilia García Torres and Lourdes Roca exposes some relevant aspects of the first indigenous cinema workshop held in November and December 1985, as well as a reading that seeks to recognize from the fictions the anthropological aspects represented in the final productions. The idea of the workshop was proposed by Luis Lapone, who had the experience of the Varan Workshops based in France, from which they have sought to train future filmmakers from different parts of the world so that they can film their own reality. Thus, Luis sought to replicate this workshop in several coordinating centers in the world. iniThe San Mateo del Mar workshop was the pilot project that gave rise to three film exercises that are discussed and analyzed in this chapter. In addition, the authors give us an account of the process to carry out the workshop, the process of finding the women participants, the creation of the scripts, the research that went behind it and details about the field work that accompanied the workshop.

The chapter "The pedagogical turn in ethnographic cinema. Dominique Jonard and collaborative animation" by Itzel Martínez del Cañizo Fernández describes part of the teaching and representation processes of this artist. Dominique's work is an exceptional case worthy of further dissemination. Her pedagogical work focuses on the children of different communities in the country -although, particularly in the state of Michoacán- bringing the production of animation to the children who are the heirs of the narratives of their communities. The author manages to give an account of the value of his trajectory as a filmmaker and introduces us to a participant of Dominique's animation workshop who is now an audiovisual producer thanks to the motivation and inspiration that the workshop gave her.

The next section is "From the aea to the transfer of audiovisual media: a paradigm shift at the twilight of the ini"Alberto Cuevas Martinez exposes the context in which economic and social policies in our country, as well as international ones, dominated at the end of the century. xx and the beginning of the century xxiThese had repercussions on the actions of the institutions on civil society, seeking to keep cultural management outside governmental institutions. In this case, in the aea The aim was to implement the Transfer of Audiovisual Media to Indigenous Organizations and Communities from 1989 to 1994, in order to promote the use of video among the villagers to create their own productions. In this sense, there were several aspects that made this initiative possible, as well as previous projects as mentioned. On the one hand, the author highlights the indigenist policies that supported these workshops, which accentuate the neoliberal schemes of the government headed by Carlos Salinas de Gortari, so that this new way of understanding representation has different interpretations. Likewise, the author highlights the scope and challenges faced throughout the process: from technological changes to the legitimization of the materials as audiovisual productions, since they have particular characteristics of the different communities.

The last chapter contains Valeria Pérez's reflection on the aeaIt is above all an invitation for a new circulation of images outside the institutions, which is pertinent and necessary. The work of editing and selection of photographs throughout the book is undoubtedly a treasure to be enjoyed and appreciated, because talking about so many images makes one want to have at hand a fragment of what was experienced.

By way of conclusions

Undoubtedly, this book confronts us with time: with the present in which we can recognize that all these social conflicts and mistreatment of the native peoples of the country, which were manifested several decades ago, are still in force and worsening; with the past, not only the past of these documentaries, but with the colonial past that lies behind, which is not of decades, but of centuries. In the same way, it confronts us with the future, in which the native peoples must be present and they are the ones who will be able to imagine a better future.

Perhaps the greatest debt of this book is not addressing the concept of "indigenous", and that among the members of the original peoples themselves there has arisen a noise and discomfort about the term; therefore, I believe that the circulation of the documentaries among the communities should also be accompanied by a broad discussion on the subject.

It is necessary to emphasize the possibility of watching the documentaries after scanning the code. qrI think it is very appropriate and, above all, it shows the multiple layers of times, spaces and even technologies, as well as fragments, glances, stories and so on that lie behind this archive. This aspect recognizes the ability of books and research to combine so many elements at the same time and to place us in different times and spaces.

Bibliography

Becerril, Alberto (2015). “El cine de los pueblos indígenas en el México de los ochenta”, Revista Chilena de Antropología Visual, núm. 25, pp. 30-49.

Contreras, Mónica (2022). “Caravana de Dignidad y Conciencia Wixárika avanza con paso firme hacia la cdmx”, Zona Docs, 17 de mayo. https://www.zonadocs.mx/2022/05/17/caravana-de-dignidad-y-conciencia-wixarika-avanza-con-paso-firme-hacia-la-cdmx/ Consultado el 31 de mayo de 2024.

Piño Sandoval, Ana (2013). “El cine etnográfico mexicano”, en María Guadalupe Ochoa Ávila (coord.). La construcción de la memoria. Historias del documental mexicano. México: Conaculta.

Rovirosa, José (1992). Miradas a la realidad. Vol. ii Entrevistas a documentalistas mexicanos. México: cuec, unam.

Filmography

Alcoriza, Luis (dir.) (1965). Tarahumara, cada vez más lejos [película]. México, 105 min. Español.

Becerril, Alberto (dir.) (1995). Generación futura México [documental]. 60 min. Español y mixe.

Contreras, Ernesto (dir.) (2017). Sueño en otro idioma [película]. México, 103 min. Español.

Cruz, Carlos (dir.) (1995-1998). Cruz Ochurte Kiliwa [documental]. México, 50 min. Koleew/kiliwa y español.

Echevarría, Nicolás (dir.) (1979). Teshuinada [documental]. México, 29 min. Español.

Heyerdahl, Ernesto (dir.) (1988). El Programa Mundial de Alimentos en los albergues escolares [documental]. México, 17 min. Español.

Lartigue, François y Alfonso Muñoz (dirs.) (1976). Sukiki [película]. México, 29 min. Español.

Mandoki, Luis (dir.). (1981). El día que vienen los muertos, Mazatecos I [documental]. México, 69 min. Español.

— Papaloapan Mazatecos II [documental]. México, 50 min. Español.

Méndez, Óscar (dir.) (1983). Raramuri Ra´Itsaara [documental]. México, 70 min. Español y rarámuri.

Muñoz, Alfonso (dir.) (1990). Días de albergue [documental]. México, 26 min.

Karla Ballesteros holds a degree in Communication Sciences from the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, a master's degree in Visual Anthropology from the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, and a master's degree in Visual Anthropology from flaccid D. in Social Anthropology from the Universidad Iberoamericana. cdmx. She has received awards and grants for audiovisuals and photographs that address migration, gender and diverse cultural practices. Her lines of research are migration, masculinities and photography as an ethnographic resource. She is currently a lecturer in the Department of Anthropology at the uam-Iztapalapa and is in charge of the Visual Anthropology Laboratory. She is a candidate in the National System of Researchers.