Wixárika art, a door of recognition to the sacred

- Isaac Mariscal

- ― see biodata

Wixárika art, a door of recognition to the sacred

Reception: August 20, 2019

Acceptance: September 4, 2019

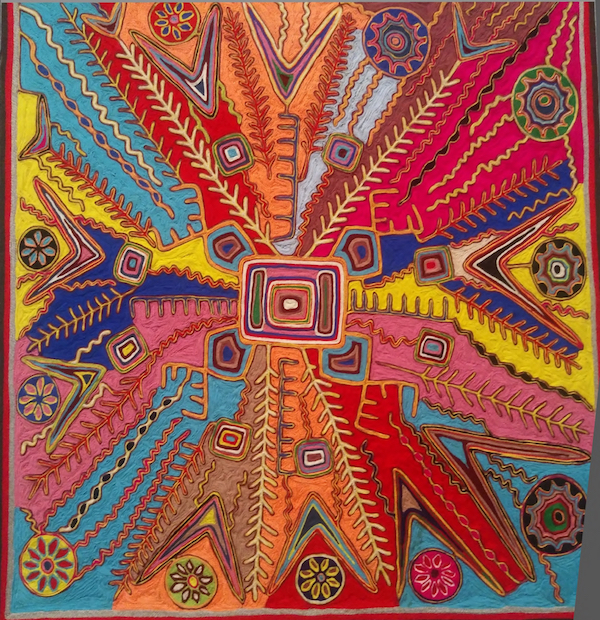

Grandes maestros del arte wixárika. Acervo Juan Negrín

Cabañas Cultural Institute, June to October 2019, Guadalajara, 84 works.

With regard to the exhibition Great masters of Wixárika art. Juan Negrín Collection, exhibited at the Cabañas Institute from June 20 to October 2019, I present the following reflections on the approach to Wixaritari sacred art through the museum or commercial medium.

Since ancient times, art has been a manifestation of the social and cultural life of peoples. As the processes of modernity were touching the traditional communities, their artistic expressions were recognized by an audience that was attracted by the exotic image, but also by the religious expressions aesthetically embodied in their works. This was the case with Wixaritari art, which was the medium with which the Huichols gained international fame. In the early 1960s, Juan Negrín was one of the few researchers who managed to establish very close relationships with the Wixaritari experts in ritual practices. They agreed to his idea that the sacred art they produced would not be used for profane use, but rather to inspire spiritual awareness in other people. "My goal was that the Huichols, who in my opinion had artistic gifts, could really dedicate themselves to a religious artistic work and thus give us a visual reading of the philosophical-religious thought of their tribe."1

According to Johannes Neurath (2013), every Wixárika ritual practice is impregnated with art and vice versa, every work of art implies the performance of a ritual. Between these two poles there is an interstice, "intermediate forms" that in a back and forth –like waves– touch the narrative representational art (such as that of paintings where the founding myths are expressed), but also tend towards the action of ritual dialogue with the gods; as well as between public art for tourists and the ritual taboo accessible only to the initiated.

It is from the clash between these "tectonic plates" that the particular Wixárika aesthetic emerges. (…) It is an art of confrontation, of paradox, that is why it would be incorrect to argue, for example, that contemporary Huichol art is a derivation or misrepresentation of ritual art (Neurath, 2013: 126).

What happens, Neurath argues, is that Wixaritari rituals already have a built-in crisis consciousness. From our point of view, this is the awareness that the Wixaritari have that their relationships with non-indigenous people are closer, daily and permanent. Ritual cannot be the exception to such exchanges and therefore art also tends to express that reality, which may seem contradictory.

Our objective with this review is to analyze this gap by focusing our attention on the double characterization that Wixárika art has: on the one hand it is sacred art and on the other it is commercial art, which due to the approach of cultures and societies can coexist at certain times. .

Wixaritari sacred art is the product of a network of ritual commitments between the Wixaritari and their ancestors: its creation means the concretization of an alliance and consequently implies equal responsibilities. Therefore, the Wixaritari do not see it propitious to produce sacred art to be exhibited in museums, much less to sell it. On the other hand, commercial art does not imply that ritual fabric of commitments, since its purpose is to produce illuminated aesthetics in the combination of colors and the fascination of the public for ancestral figures that allude to a mysticism that is often romanticized. Hence the great success of Wixárika artistic production.

On the other hand, museum art originates from authentic ritual works, but also from mythological narratives that the Wixaritari share with anthropologists studying their culture and a demand from the foreign market, collectors and spiritual seekers. So a portion of museum art may also be destined for sale to a public attracted by Wixárika mysticism. However, this type of art keeps the collective memory of a people in time, so it has the function of safeguarding a cultural heritage, and it is important because the studies that seek to understand the past and the past depend on that. different cultural groups due to physical and cosmogonic distance. This allows those of us who are not immersed in that other culture to have the means in that collection. So it is necessary that museum art be bridged with the living culture of traditional communities in their day-to-day lives, in their struggles and challenges.

Precisely what is sought in any art show is to connect with the sensitivity of the attendees and their desire for understanding. Perhaps this is the first step that a teiwari (mestizo) can lead to an encounter in which the need to understand the other is prioritized rather than the desire to obtain it for oneself, as is often the case when buying commercial artistic pieces.

An anecdote that can serve to understand how ritual art allows building bridges between the physical and spiritual worlds is the following: in Taimarita, a community of the Wixárika Taizán family, located near Tepic de Compostela, Nayarit, it was the dawn of the year New from 2010 when I was able to contemplate the mara'akame Don Pablo design and make one of the popular yarn paintings. The old man looked to the horizon and returned to his painting with wax while tracing hills and mythological figures. I asked him what he was doing and he said he was portraying the new year. I did not think that the old man was making a portrait, like that of a painter. I always believed that yarn paintings were based on patterns designed in advance. But there in the painting, through a special symbology, the mara'akame He was capturing the figure of Father Sun coming out of the mountain, while other deities were in dialogue with him. This experience was special because it allowed me to be a witness to the process of artistic production, which in turn recreates the process by which it shows us the spirits doing projects about the future. On another occasion I managed to observe the same artist and mara'akame making a picture of yarn: Pablo Taizán told me what the spirit of a place to which he had been invited had expressed to him; days later this painting was bought by the owner of the site.

Wixaritari art is one of the main means of subsistence and work for this cultural group; It is common practice for many Wixaritari to recreate commercial imitations of other paintings - created not for commercial purposes - for the public attracted by the ancestral air of these works. However, Wixaritari sacred art transcends the decorative; it crosses the barriers of habitual communication insofar as there is a memory that can be activated, and with which, from its belief system, it is possible to literally enter into dialogue with otherness, because it is a living, performative memory that if properly contemplated with a preloaded cosmogonic heritage, communication may be assumed, or as the Wixaritari themselves say, “speech” with what previously seemed striking but inert objects. This type of art, we must say, transcends the commercial and even more transcends certain classical anthropological observations, because it is an art that lives and gives life to those who are willing to interact with the cultural reality they observe and who, through their meanings, integrates.

In this sense, an authentic artistic cultural heritage is of great value. For example, him mara'akame Pablo Taizán pointed out in life the importance of what he had left to Juan Negrín. He said that as many of the monoliths representative of the gods had been lost, and few mara'akate They could sculpt the ancestors, which is why he dedicated himself to carving many figures in order to safeguard all the ancestral memory of the Wixaritari deities, so that, when a sculpture for the god was needed, a copy could be made. Wixaritari museum art is a key sample for this and it is important that it be a source of consultation, because even for Wixaritari who already know more about the worldview it can be a valuable source to keep alive the sense of sacred knowledge, that is, the custom. In addition to the aforementioned symbolic value, the important thing about this art as a cultural heritage for the public's contemplation is that we are talking about Wixaritari sacred art legacy as a heritage for humanity. This was a somewhat daring movement of the artists, but necessary to safeguard it, since being artists who at the same time perform a ritual practice that implied revealing knowledge that should or usually be kept in reserve.

Neurath (2005) has already said it, there is a cultured art and a commercial one. Commercial art is splendidly aesthetic, but its meaning does not usually reflect a coherent religious sense, because the artists do not want to sully the deities by subjecting their representation to a context outside their ritual dimension, which would attract punishment and sacrifice.

To avoid health problems, artists often stopped making visionary works and preferred to make handicrafts devoid of religious significance. One strategy to avoid religious meanings is the random combination of icons. (…) The same reasons are used, but they are arranged in an arbitrary way. In other words, they are designs without a syntagmatic dimension (Neurath, 2005: 22).

According to Arriaga and Negrín (2018), many avoid making pictures with yarn because it has a symbolic ritual charge and commitment to the ancestors. Neurath adds that “the chaquireados would be less problematic objects” (2005: 40-43). The same author points out that the production of commercial Wixaritari art responds to a buying and selling logic for people eager to “consume some impressions of indigenous shamanism and wisdom” (2005: 23). So their representations allude to a non-indigenous decorated as indigenous, there is a double masking, it is an art "of the other of the other."

However, as an alternative to this logic of consumption, in this type of artistic representations we can also find a genuine intention and vision of Wixaritari artists. In some cases it is not only about selling, but the vision of the rejuvenated and revitalized Wixárika culture is expressed with the incorporation of the non-indigenous. It is also their hope for us, so that we recognize the sacred Wixárika and look for it in our lives, since they consider that we are brothers; is the invitation to that lost younger brother (in mythology)2 to now rediscover a new, more human and deified path. They are the hopes of some Wixaritari who on many occasions run into marketing invasion, consumption, ritual depredation and natural resources. As has happened with the sacred cactus hikuri, at risk of extinction from the constant looting of spiritual seekers and merchants on Wirikuta.

As has been said, museum art is established at a midpoint between commercial and sacred art. There, pieces of authentic value for the Wixaritari converge, it is a living memory but in repose. Unlike the sacred art of the communities, which is active and active, with which the Wixaritari and those initiated in the knowledge of their culture can dialogue, a work protected in the museum can serve at a certain moment to refound the traditional memory already turn inspire watchers. With these cultural heritage we are given the opportunity to carry out an understanding exercise through contemplation and study of said material.

How to comprehend understandingly deciphering the Wixaritari by studying their artistic production? Are they sellers or producers of culture? We can say that the Wixaritari continue to produce culture in each exchange meeting. We can only marvel at how they have managed, in an increasingly surprising way, to penetrate a different culture and allow themselves to be impacted by it, as well as strongly influence it. The logic of consumption with which many Wixaritari artists work can also be translated as a spiritual conquest not through violence, as happened in the colony with them, the indigenous people, but through art, with appreciation, love and hope, but also with zeal and prudence. Therefore, from the cultural logic of the Wixaritari, revealing culture in art and ritual implies a serious commitment to the deities. But in the consideration of many of these ritual specialists it is well worth taking the risk if teiwari They need it, because this exercise is circular and that could be beneficial for the traditional life of the communities.

So how to decipher the art of the Wixaritari, the murals, the works of various artists taken to foreign museums? What is its value and what is its representation? What would be the logic in awarding these pieces for exhibition in the museum? In the case of the Negrín collection (exhibited in the Cabañas museum), the cultural depth with which the artistic works are expressed is impressive. By observing the paintings, one can make a reflective projection of abstraction to be transported to the mythical plane and in this way observe the birth of the first times, of the first gods, of the challenges that were overcome so that the ancestors received the cosmological forces and these were kept in balance. Other paintings show us the conception that the Wixaritari have about death and the successive steps when dying. A worldview is evidenced that proposes a continuity after death under stages of experiences that are related to the actions carried out in life. But also the sample of the Negrín collection offers us the enormous appreciation that the Wixaritari have for their deceased wise relatives, who due to their spiritual quality ascend to the mythical temple of the deities and are spiritually brought to the community and densified in small crystals that are placed in the altar of the temples or shrines, xirikite or tuki, also called kaliwey. Those spirits (+ r + kamete) will be the guides and will give advice to the inhabitants of the place. This gives us a conception in which spiritual forms and sacred knowledge after death continue as a living and pulsating heritage. Other paintings show long and complex myths that are sung during a whole night of ceremony, so the painting can be interpreted as a book from which one can meditate while abstracting to get closer to the understanding of Wixárika thought.

The Wixaritari are aware that they have never been isolated, so these moments of cultural exchange give us the possibility that the people of the city open their eyes and understand what they keep there in their ritual art. However, understanding is not just doing an exercise in interpretive reasoning of cause and effect. It implies an exercise with the hands and with the heart, an exercise, a work towards the interior and the exterior with the culture that one seeks to embrace.

Once the old woman Lucía Lemus, when she recorded a prayer that she made to the divinities, told me: “With that - pointing to the tape recorder - you are not going to learn, you can only learn with this - pointing to her heart - and with this - the head-". So intercultural understanding implies taking a step beyond a classical external observation; nor is it about romanticizing the other. Sarah Corona (2007) says that it is an interculturality, that is, of recognition, of the difference in the other because we are not the same, and that difference is precisely the basis of respect and appreciation that will arise between different cultures. Based on that and on a horizontal (non-paternalistic) dialogue, joint efforts could be used to help each other.

In the meantime, let us continue making the intellectual and moral effort to transform our way of observing the art of other cultures, and more so in the case of a very lively one that, although it is based on their geographically remote communities, is in turn here among us, with the young, with the Wixaritari who come to the city to study and work, with the elders of wisdom who are called by non-indigenous people. But there is also a physical closeness and a cultural distance; how to take that challenge depends on us.

Perhaps these artistic works are a door, an invitation to recognize a different culture and cosmogony. For this we need to look and observe with enough sensitivity that transcends the desire to possess the pieces to decorate the home, with the intention of acquiring an understanding of their religious and cultural practices. Our point of view is that to achieve this understanding it is essential to acquire the disposition that is required of students of philosophy. According to García Morente, the childlike disposition of admiration is necessary:

perceive and feel wherever you want, in the world of sensible reality, as in the world of ideal objects [spiritual wixaritari] problems, mysteries; admire everything, feel the profoundly arcane and mysterious of all that, stand before the universe and the human being himself with a feeling of stupefaction, admiration, insatiable curiosity, like the child who does not understand anything and for whom everything is a problem ( 1994: 24-25).

The same author points out that "the spirit of rigor, the demand for accuracy" is also necessary. For our purposes, we classify this rigor as "cultural", because it is not possible to follow a thought of reasoning like that of philosophy, but a philosophical hermeneutical sensitivity with which one has the disposition to find answers to different rationalities. However, the rigor will always be satisfied with the participation of the experts of the native culture. So we could not take our speculations further without the wixaritari themselves showing us once again the mythical and ritual path to which the work of art we observe belongs, or sufficient evidence to support our hypotheses. The first guide will be the description next to the pictures; this will be the starting point from which we can deepen the worldview of the Wixárika culture. Finally, it is necessary to remember that understanding the sacred art of another culture does not mean that its world has been penetrated. It only implies the intellectual and intuitive sensitization towards the other. The only way to achieve a deeper understanding is through intercultural embrace, and that implies social relationships, work and participation in activities that are useful for the subjects of both groups.

The Wixaritari learned to value the religious art of other cultures; in the colony they had to forcibly adapt it as a means of survival. Thus, the pictures and images of some Catholic saints became part of the Huichol sacred pantheon. However, they drew parallels, linked Christian sacredness with their own sacredness. Now many of the religious images of their traditional temples are Catholic images, but they preserved in the background of those images the ancestral Wixárika identity while they became flexible towards the other culture.

In this sense, a museum collection saves the efforts and sacrifices so that the cultural and identity portent is safeguarded and a little later it is opened as a base of study and learning for future Wixárika generations and for those with the genuine interest of respectfully recognizing a culture "Other", different, but with the need to move forward, to fulfill the sacred produced there "so that it is not lost custom”And for us to transform our gaze and thus try under a different paradigm to approach more harmoniously.

Bibliography

Corona, Sarah (coord.) (2007). Entre voces… Fragmentos de una educación “entrecultural”. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara/Pandora.

García Morente, Manuel (1994). Lecciones preliminares de Filosofía. México: Porrúa.

Arriaga, Ingrid y Diana Negrín (2018). “Arte y procesos creativos en la circulación de la espiritualidad wixárika”, en Carlos Alberto Steil, Renée de la Torre y Rodrigo Toniol (coord.), Entre trópicos. Diálogos de Estudio Nueva Era entre México y Brasil. México: ciesas.

Negrín, Juán (1985). Entrevista personal con Javier Ramírez. “La visión de Juan Negrín sobre el arte wixárika”, Partidero. Disponible en https://partidero.com/la-vision-de-juan-negrin-sobre-el-arte-wixarika/. Consultado el 2 de septiembre de 2019.

Neurath, Johannes (2013). La vida de las imágenes. Arte huichol. México: Artes de México/conaculta.

Neurath, Johannes (2005). “Máscaras enmascaradas. Indígenas, mestizos y dioses indígenas mestizos”, en Relaciones, núm. 101, vol. xxv, pp. 23-50. https://www.colmich.edu.mx/relaciones25/files/revistas/101/pdf/Johannes_Neurath.pdf, consultado el 2 de septiembre de 2019.