The hinge in the religious phenomenon: the diversity of the sacred in contemporary Mexico.

- María Fernanda Apipilhuasco Miranda

- ― see biodata

The hinge in the religious phenomenon: the diversity of the sacred in contemporary Mexico.

Receipt: August 27, 2024

Acceptance: October 30, 2024

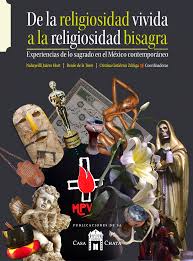

From lived religiosity to hinge religiosity. Experiences of the sacred in contemporary Mexico.

Nahayeilli Juárez Huet, Renée de la Torre, Cristina Gutiérrez Zúñiga (Coordinators)Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2023, Mexico City, 809 pp.

I am grateful to the Postdoctoral Fellowships Program at the unamand to my advisor, Dr. David de Ángel García, for the support received.

From lived religiosity to hinge religiosity. Experiences of the sacred in contemporary Mexico. Nahayeilli Juárez Huet, Renée de la Torre, Cristina Gutiérrez Zúñiga (coordinators). Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2023, 809 pp. isbn: 978-607-486-677-3

In the book From lived religiosity to hinge religiosityD. and coordinators Nahayeilli Juárez, Renée de la Torre and Cristina Gutiérrez share with us a long-range research -of national scope and plural dimension- on the subjectivity of religious life and its diversity in contemporary Mexico, in which quantitative elements and qualitative methods are used to provide a powerful analysis to understand religious plurality through two key concepts and methodologies: lived religiosity and hinge religiosity. These are also applied and analyzed by 21 researchers -with expertise in different religions- whose work, together with that of the coordinators, make up the body of the book.

The book as a whole challenges the reader in multiple ways, from the existential sphere (which considers the homo religiosus as a human dimension -Mircea Eliade-), to the academic, first as researchers with respect to their own methodologies, the ways in which they relate to their interlocutors and their voice in ethnographic works; and as a relevant proposal in studies of the religious field -mainly sociological and anthropological-, which puts on the table the discussion in the social sciences on structure and agency.

Given the complexity and length of the text, this review is divided into three sections: the first one presents the general proposal of the coordinators; the second one presents how the book is articulated from its 27 chapters; and finally, in the third section, some resonances of the theoretical proposal of the hinge with respect to Latourian-inspired concepts such as node and ontological uncertainty are enunciated.

Extraordinary research

In general terms, this book is the result of previous research work by the coordinators.1 Since 2017, they have been in charge of studying religious diversity in Mexico based on quantitative sources such as the censuses of the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics (inegi), and the National Survey of Religious Beliefs and Practices (Encreer, 2016), based on which they expose the reconfiguration of the religious field in Mexico as a slow but sustained process (p. 21). Their interest is to account for the "different ways of living religiosity in Mexico, in which religiosity is diverse and represents frameworks of cultural differentiation" (p. 21). One of its aims is to contribute to a culture of acceptance, appreciation and respect for religious otherness (p. 21).

The coordinators are interested in knowing how people live their religiosity and the sacred, from everyday life and materiality, how they construct it from different cultural and religious logics, and the decisions they make from their biographical history and as subjects situated with respect to social class, gender and age group, among others. Therefore, they emphasize the experience of the subject who is within the framework or at the margin of religion in terms of institution, but which does not determine it. Here, the religious structure or system does not serve as an interpretative framework for the action of the religious actors, but allows the actors to guide and show the multiple ways of constructing the religious from their life experience (crossroads, crises, adversities, political positions, dissidence, criticism, among others) and how this is not lived in the abstract but from the materiality (objects, places, spaces, the body, prayers, prayers, among others). This proposal does not imply individualizing the analysis and leaving it as isolated cases, but situating the stories of the subjects in their broader social context (p. 719).

The coordinators discuss the way in which the religious phenomenon is usually studied, mainly from an institutional and census perspective, and propose a phenomenological methodology based on the concept of everyday religion or lived religion, which shows how subjects construct their interpretative frameworks for being and being in the world based on their religiosity. These frameworks do not emerge from nothing, but from a social context that implies the individual's position in family, neighborhood, local and national terms.

Thus, the reflexivity of the subjects, their conditions, possibilities and dynamism in the religious field (religious mobilities) that generate dynamic belongings and identities, political positionings (feminisms or environmental practices) and modes of economic subsistence throughout life are highlighted.

The gear

Juárez, De la Torre and Gutiérrez brought together a group of researchers with expertise in various religions and religiosities in Mexico to explicitly employ the methodology of lived religiosity. This group had as its axis the implementation of an interview guide and the recording of materialities (included in the annexes of the book), which each one complemented with other ethnographic tools. Although they had a very marked guideline: the interview and the analysis, as well as the collective discussions, each author put her own stamp; some had a previous link of several years with the interviewees, which is noticeable in the depth of their analysis, such as the work of David de Ángel, Gabriela Gil, Antonio Higuera and Cristina Mazariegos. Thus, there are very rich descriptions that place the reader in the space of the interview, and descriptions of the interviewees that make one's skin crawl with respect to their experiences and feelings. There are also voices that are not so convinced of the methodology, but that expose its possibilities and limitations, and those that even question themselves with respect to the questions and observations that they elaborate from a logocentrism, epistemocentrism or western ontology, as is the case of Cristina Gutiérrez and Gabriela Gil. In the chapters we can find the expertise of the authors with respect to the religious system in which the actors are drawn or blurred. It is very important to highlight that each researcher exposes what he/she understands as materiality, in some cases they thematize it from latitudes such as ontologies, the diverse ways of being of objects and their relations with humans (see Renée de la Torre, Gabriela Gil, Olga Lidia Olivas, Cristina Gutiérrez, Arely Medina and Adrián Yllescas).

The structure of the book takes into consideration two key elements: statistical trends on the recomposition of the religious field in Mexico, and how this is experienced in people's daily lives (p. 22). Therefore, the cases presented were chosen in order to represent the current religious diversity and to exemplify the different regions and socio-demographic variables -age, ethnicity, sex, socioeconomic level and level of education- (p. 22). Thus, the work is composed of a general introduction, 27 chapters and general conclusions. From the first page, the care taken by the coordinators in terms of rigor, dialogue with the authors of the chapters and, above all, the voice of the interlocutors, is evident.

The book is divided into three sections whose objectives are to account for religious diversity, even within apparently well-delineated and structured religions such as Catholicism and Evangelicals or Christians. The first section, "Catholics" -with seven chapters- was coordinated and introduced by Cristina Gutiérrez, in which an account is given of the regional and ethnic diversity of Mexican Catholicism, a religion currently professed by 77% of the population according to the 2020 census (p. 64). The emphasis is placed on showing the internal differentiation of Catholicism, which implies a regionalization model based on its historical configuration and its ethnic diversity from the indigenous groups in terms of syncretism (p. 64 and 65). Thus, we can read testimonies of a critical and liberationist Catholic from Cuernavaca, Morelos (Cecilia Delgado-Molina), an "Ibero girl" of Opus Dei from Mexico City (Gabriela García), a young Catholic from Guadalajara, Jalisco (Anel Victoria Salas), a non-practicing Catholic from Guadalajara, Jalisco (Renée de la Torre de la Torre), a young Catholic from Guadalajara, Jalisco (Anel Victoria Salas), and a non-practicing Catholic from Guadalajara, Jalisco (Renée de la Torre), Jalisco (Renée de la Torre), a Mayan Catholic from Nunkiní, Campeche (David de Ángel García), a Catholic Rarámuri with his traditional customs from the high Tarahumara in Chihuahua (Gabriela Gil), and the charismatic experience of a Tseltal migrant woman in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas (Gabriela Robledo).

The second section corresponds to "Christians" -with nine chapters-, coordinated and introduced by Renée de la Torre, which gives an account of the plurality of Christians or evangelicals that today make up 11.2% of the Mexican population (inegi 2020). Here it is shown how the particularities of the cases generate cultures that demand religious adaptations, whose trajectories of multiple religious mobility involve constant negotiations, articulations and integration (p. 248). Also noteworthy is the approach to materiality in the daily lives of the interlocutors, as it shifts from conventional sacred objects to the body, domestic or intimate spaces and prayer, among others. The experiences are of a Methodist-feminist woman from Guanajuato (Hilda María Cristina Mazariegos), a Presbyterian from Xalapa, Veracruz who lives her religion with freedom (Felipe R. Vázquez), a Pentecostal from Ciudad Juárez (Patricio Vázquez), a Tojolabal Pentecostal in Chiapas (Enriqueta Lerma), a young evangelical-Pentecostal from Tijuana, Baja California (Carlos S. Ibarra), a homosexual of dissident evangelical identity from Mexico City (Karina Bárcenas), an Adventist woman in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas (Minerva Yoimy Castañeda), an immigrant Jehovah's Witness in Chetumal, Quintana Roo (Antonio Higuera), and a Mormon woman from Aguascalientes (Genaro Zalpa).

The last section is entitled "Without religion and minority religions" -with eleven chapters-, coordinated and introduced by Nahayeilli Juárez, which encompasses the experiences of disaffiliated and non-affiliated people who explicitly do not belong to a religious or ecclesiastical institution (p. 453); in a single section it groups together people with their own spiritual path (p. 454), and people within minority religions in the country. Thus, in this section one can find a tantric priestess from Mexico City (María del Rosario Ramírez), a doctor in literature self-styled as spiritual, deep in the Wixárika cosmovision from Guadalajara, Jalisco (Renée de la Torre), a follower of Krishnamurti in Guadalajara, Jalisco (Cristina Gutiérrez), a lay Zen in Mérida, Yucatán (Nahaye de la Torre), a follower of Krishnamurti in Guadalajara, Jalisco (Cristina Gutiérrez), and a lay Zen in Mérida, Yucatán (Nahaye de la Torre), Yucatán (Nahayeilli Juárez), a practitioner of the Mexican-Lakota path in Tijuana, Baja California (Olga Lidia Olivas), a homosexual Mason in Aguascalientes (María Eugenia Patiño), a Muslim in Guadalajara, Jalisco (Arely Medina), a Jew in Guadalajara, Jalisco (Cristina Gutiérrez), a Marian Trinitarian spiritualist in Veracruz (Gabriela Castillo), a Santero and coach spiritual in Mérida, Yucatán (Nahayeilli Juárez), and a Santa Muerte devotee in Mexico City (Adrián Yllescas).

It is important to emphasize that the book as a whole and the methodology employed take seriously the word, the feeling and the materiality of the other (with careful and beautiful photographs, by the way), in one term: their experience in the world, without limiting, classifying or simplifying it, but rather taking into account its scope, limitations, complexities and, above all, the reflexivity of the subjects with agency, capable of deciding and interpreting -within determined frameworks- their being and acting.

In this way we find agents who communicate their need to believe in something or someone in a reflexive and critical manner, as well as the materialization of their beliefs, their transitions between different religions, their constructions about the sacred, about the body, about the family, about the person, about gender, about death and the meaning of their existence through the sacralization or contemplation of their daily lives and their relationship with others and with the environment. This is glimpsed in a diverse and heterogeneous way, but as a constant in all the chapters.

In the conclusions of the work, the coordinators compare and analyze the chapters as a whole, and share their theoretical-methodological contribution: hinge religiosity, from a phenomenological and materialistic approach, which implies understanding the religious phenomenon from the concrete experience situated as a process and not as preconceived classifications (p. 723), which is not only due to an institutionalized religious logic, but to the assembly that each subject makes from his or her life experience. The hinge religiosity is then, a relational perspective, an articulation of anchorage and dynamism, that are

points of articulation where individual expectations are negotiated with the system of institutional norms and values, the adequacy of changes to traditions and the validity of faith in secular spheres [...] offers the possibility of imagining concepts not based on oppositions but on intersections and complements set in motion from everyday religiosity (p. 726).

Thus, from this approach, the religious phenomenon can be understood as a polyphonic concept composed of different melodies, ranging from the reflective experience of individuals to institutional norms.

Resonance

Finally, the theoretical-phenomenological contribution of the coordinators to the religious field echoes with some elements of pragmatic perspectives such as the Actor-Network Theory (tar). The coordinators slide from lived religiosity to the hinge, blurring apparently dichotomous or binary classifications and notions, and placing materiality as a central element for their analysis. The usefulness of the hinge lies in "naming interstitial processes that articulate different religious traditions and that occur simultaneously in the same event" (p. 728); it is, then, a point of contact "where different currents, scales or contents are articulated and the hinges operate as anchors, where emerging religiosities interact with traditional ones" (p. 728). Such mobility of classifications and articulation resonates with two Latourian notions that point to the authors' contribution.

The first is the principle of ontological uncertainty which, in the study of practices, implies not establishing the agency a prioriThe aim is to be guided by the principle of uncertainty; that is, to have a lack of certainty of the goals in social interactions in order to trace the action of all the actors involved. Consequently, it is not necessary to establish essences of subjects and objects, nor to create fixities or goals around them (Latour, 1994). This coincides with the coordinators in considering that the hinge religiosity supposes adaptations of the subjects -through their experiences- to religious diversity, so that the emphasis is on the dynamics of identification and not on pure or closed identities that provide the fixity of religion in institutional terms (p. 732). The second is a notion of node inspired by Bruno Latour, understood as an articulation where many sets of agencies converge and act simultaneously (Apipilhuasco, 2021: 5). Although the node for Latour dissociates itself from the informatics that plans the node as an articulation (cfr. Latour, 2008), it is feasible to rethink it as such, in methodological terms, connecting with what he does consider: "the action must be understood as a node, a knot and a conglomerate of many surprising sets of agencies and that have to be slowly unraveled" (Latour, 2008: 70), it does not have a defined structure, it does not have a strategic character, it is not fixed and has as many dimensions as connections (Latour, 1996: 369 and 370). To characterize action, events and even materiality as a node consists in thinking of it metaphorically as a place where connections are made and transit diverse sets of actions that are neither fixed nor established, they are in constant dynamism, depending on all the human and non-human actors involved in them (Apipilhuasco, 2021). This refers to the hinge as that space of articulation where diverse religions interact, from which "syncretic and hybrid products derived from religious goods and meanings result" (p. 728).

In this way, the hinge, together with the ontological uncertainty and the node, can be notions that help in the investigation of the religious field, as elements that allow the generation of methodologies that start from a perspective that is based on the following emic -The main objective of this study is to understand the mobility, diversity and dynamism of religious identities, framed in a broad social context.

Bibliography

Apipilhuasco, María Fernanda (2021). “Ñatitas. Producción, agencia y ritualidad de los cráneos en La Paz, Bolivia”. Tesis de doctorado. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán.

Latour, Bruno (1994). “On Technical Mediation: Philosophy, Sociology, Genealogy”, Common Knowledge, vol. 3, núm. 2, pp. 29–64. Recuperado de https://philpapers.org/rec/latotm

— (1996). “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications”, Soziale Welt, vol. 47, núm. 4, pp. 369-381. Recuperado de http://www.jstor.org/stable/40878163

— (2008). Reensamblar lo social: una introducción a la Teoría del Actor-Red. Buenos Aires: Manantial.

María Fernanda Apipilhuasco Miranda D. in Social Anthropology from El Colegio de Michoacán and a B.A. in Sociology from the School of Political and Social Sciences of the University of Michoacán. unam. He has conducted research projects in Janitzio, Michoacán, La Paz, Bolivia and Pomuch, Campeche. Her research topics are sociology and anthropology of religion, myth, anthropology of death, indigeneity, patrimonialization and ontologies of the central Andes. She is currently in her second year of postdoctoral stay at the Centro Peninsular en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.