The Fiesta de los Arcos: the renewal of the alliance between the ancient Indian villages of Lagos de Moreno.

- Hector Medina Miranda

- ― see biodata

The Fiesta de los Arcos: the renewal of the alliance between the ancient Indian villages of Lagos de Moreno.

Receipt: June 3, 2024

Acceptance: September 9, 2024

Abstract

The article describes the ritual performed by the three ancient Indian villages of Lagos de Moreno (Jalisco, Mexico) in which they renew a long-standing alliance and reclaim their common history and origin as indigenous societies. It is an act of resistance to attempts to deny or make them invisible in a context of adverse policies.

Keywords: Indian villages, ritual, original societies, territory

festival of the archesa renewed alliance among pre-hispanic indigenous peoples in lagos de moreno

A ritual jointly organized by three Pre-Hispanic Indigenous peoples in Lagos de Moreno (Jalisco, Mexico) is the topic of this article, which examines how an old alliance has been renewed to reclaim a common history and a shared origin of these indigenous societies. The ritual here is an act of resistance in the face of detrimental state policies and attempts to deny the existence of these peoples or erase them.

Keywords: indigenous peoples, territory, ritual, aboriginal societies, plunder.

Introduction

The Fiesta de los Arcos is a celebration that involves the three ancient Indian villages located north of the city of Lagos de Moreno, in the region of Los Altos Norte de Jalisco. It is held to celebrate Our Lady of Candelaria, the patron saint of the town of Buenavista, which invites the towns of San Juan Bautista de la Laguna and Moya. All three claim to have a shared autochthonous origin and the celebration seeks to vindicate this origin, their identity and their unity. Many people call it the "celebration of brotherhood" and consider that this is part of the struggle they sustain in favor of their recognition as indigenous peoples and the defense of their rights, a movement in which the role of women has had enormous relevance (Facio, 2021; Guzmán, 2024).

Municipal and state authorities have been ambiguous in their position regarding the vindication of indigenous peoples. Although in tourist information brochures these peoples are mentioned as part of the local attractions, in recent years they have been denied their right to self-representation and to make decisions about their territory. In these cases it is said that the indigenous peoples no longer exist, that they have been "amestized", that they are now colonies of the city of Lagos de Moreno and that the municipality has the power to make decisions regarding their resources. This position is very convenient when concessions have been granted to private companies to form an industrial corridor over the space that has been occupied by indigenous peoples for centuries. The overexploitation of resources has generated important changes in the environment, the water of the lagoon that is at the heart of their habitat and that has been fundamental to satisfy their needs has been depleted.

In this article I will refer to the origins of these Indian villages, historical episode in which the informants located the beginnings of the celebration. Then I will approach the Fiesta de los Arcos from the ethnographic observations I have made between 2023 and 2024, the year in which I can attend this celebration.1 Finally, I will briefly describe the problems they have to face, what their claims are and the way in which the Fiesta de los Arcos becomes an act of resistance, but also of renewal of the alliance between those who consider themselves descendants of the original inhabitants, in the face of the frequent attempts to deny or make them invisible.

The three Indian villages of Lagos de Moreno

Lagos de Moreno and the adjoining Indian villages were part of a region that was known as Los Llanos. Peter Gerhard (1996 [1982]: 136) suggests that, at the time of contact, this may have been inhabited by Chichimecs, perhaps by those who were identified as Guachichiles. Under these denominations, the Spaniards and their allies grouped an enormous diversity of societies that, at present, are difficult to identify by language or ethnic affiliation, so we cannot give a clear account of the social profile of the communities that made up these peoples, although it is undeniable that they were Native Americans.

Gerhard also asserts that the area came under Spanish control in the 1530s and the village of Santa María de los Lagos, later renamed Lagos de Moreno, was founded in 1563, "as a fortified point to protect traffic to and from Zacatecas against Chichimec raids, as well as to defend the Neo-Galician frontier against claims from New Spain" (Gerhard, 1996). Subsequently, between 1605 and 1610, the final demarcation of the mayor's office of Lagos was established.

Alonso de la Mota y Escobar recorded that the village of Los Lagos began to be settled in 1561, "for the convenience of some unqualified and unknown Spaniards" (1940 [1605]: 121), motivated by the great fertility of the land and the desire to establish a point of defense against the "brave Indians". The date of origin of the village of Santa María provided by Gerhard seems to be accurate, as this has been corroborated by the documentation presented by Andrés Fábregas (1986: 83), as well as in the detailed research carried out by Celina G. Becerra Jiménez (2008: 33, 69, 75, 313), who gives an account of the foundation orders and points out that it was one of the best spots in the Alteña geography, with very good land and water in abundance provided by the confluence of two rivers and a lagoon. Undoubtedly, it was a suitable space for orchards and cattle. The town had been created in a district with ambiguous boundaries that was recognized as the mayor's office of Pueblos Llanosinstituted in 1549.

Gerhard considers that the village of Santa María de los Lagos was, at first, a congregation of poor ranchers and farmers who achieved prosperity after peace with the Chichimecas and whose population multiplied in later years (1996 [1982]: 139). Later, he states that San Juan de la Laguna was the first Indian town founded in the vicinity around 1570. De la Mota y Escobar's chronicle assures that, by the first decade of the century xviiAround the lagoon there were twenty settlements of Indians "whose occupation is fishing, and on its banks there is also a quantity of yerba mate, which they call tule" (1940 [1605]: 123). The production of tule objects has been very important for these populations, which is still practiced as part of the tradition and is considered an element of identity. It should be added that the chronicler refers to the excellent quality of the pastures that allowed the rapid creation of cattle ranches. The creation of the villa and the estancias required, as in other places in New Spain, the concentration of the Indians in towns and behind this phenomenon lies the advance of the Hispanics on the land of the Indians.

Celina Becerra (2008: 115) affirms that the year 1606 could be considered the date of the foundation of San Juan de la Laguna, when the oidor Juan Paz de Vallecillo -during his visit- attended to the request for land endowment of the natives. Although the town already existed de factolacked that character and the inherent benefits. Becerra reached this conclusion after reviewing the account of the oidor's visit, published by Jean-Pierre Berthe. et al. with the paleography of Thomas Calvo, in which the following can be read:

Being in the said town he went three times on three different days personally to the village of the Indians of San Joan de la Laguna and visited them and gave them lands for their work and sowing, for being next to the said village and contiguous with it and not having in which to sow or till, which he took with his citation to Father Alonso Lopez [de Espinar], cleric, and in his presence that many years had been deserted and uncultivated by him or by the Indians, to whom he reserved his right either for them or to give him others that he might ask for elsewhere and without prejudice to his right, with which the Indians were very happy and in the spirit of continuing that population and increasing it, which was becoming depopulated because they had no land for their farming and breeding and the necessary land for the said Villa de los Lagos and for the strangers and passengers. et al., 2000: 81).

The fragment makes it clear that the endowment was, rather, an act of restitution in the face of an invasion that reduced their subsistence capacity. The reinstatement of the land allowed the town to increase its population in 1669 (Becerra, 2008: 116). Carlos Gómez Mata, the chronicler of Lagos de Moreno, in his book Indian Lakesindicates that the primitive nucleus that would form the town of San Juan de la Laguna already existed at the beginning of the century. xvii and that it received its first legal recognition in 1644 (2006: 72).2 It also adds that over the centuries, it has been xvii and xviii were recorded in various documents that today are kept in the Archive of Public Instruments of the State of Jalisco. With these he confirms that the measurements were made in 1672, date that corresponds with the official foundation of the town of La Laguna, although they already had other previous grants and acquisitions arranged by their brotherhood, recognized in 1644 by General Cristóbal Torres. Gómez Mata calculates that, through grants and purchases, the town of San Juan accumulated more than 2,000 hectares of communally owned land (Gómez Mata, 2012: 72-73).

With the creation of this town, the principle of residential separation between Indians and Spaniards became a reality and the necessary conditions for the existence of the two republics were established; this was intended to promote evangelization and ensure labor for the urban area, while at the same time integrating the natives into the Hispanic economy. It should be added that in 1669 the Indians were the majority in the region and, in 1676, a new indigenous settlement called San Miguel de Buenavista was registered, whose founders were originally from La Laguna. By the xviiiThe mestizaje was notable and the indigenous population was concentrated in the towns of San Juan de la Laguna and Buenavista, although some were also registered in the cattle ranches (Becerra, 2008: 116-117, 121-126, 129).

San Juan de la Laguna was the first Indian republic in the vicinity of the head of Santa María de los Lagos, which perhaps attracted many Indians from different groups and languages, which could have caused the split of some families to form Buenavista, according to the hypothesis of Becerra (2008: 139). They received recognition as an autonomous town in 1691 with the denomination of San Miguel de Buenavista, in spite of the opposition expressed by the inhabitants of La Laguna. They immediately undertook the expansion and reconstruction of their church, which assured them autonomy and avoided subjection to another town.

At the same time a new town was formed on the lands adjacent to the Santa Cruz de Moya hacienda and was named Limpia Concepción de Moya. Its population could have been made up of laboring Indians from the latifundia and landless Indians from the surrounding area. In order to receive recognition as a town, they had created a brotherhood of Marian invocation and as such requested a cavalry of land from the hacienda of Moya; later, in 1716, they requested the grant of nearby lands that they supposed to be realengas (Becerra, 2008: 140-142). Regarding these three cases of foundation -La Laguna, Buenavista and Moya-, Becerra considers that they are not the product of forced congregations in the strictest sense of the term, but of initiatives of the Indian population. However, it is worth reflecting on whether these decisions were not also a defensive response to the accelerated appropriation of the space by Creoles and Spaniards, an initiative with which the natives tried to guarantee the possession of a portion of land for their subsistence. Although many people in the village did not agree with the recognition of these lands and competed for them, they all knew that these settlements would allow them to ensure that they would have cheap labor in the vicinity.

Before the end of the century xviiiEach of the Indian villages had a confraternity that managed its own livestock for the maintenance of its temples and religious activities. They had autonomy, but they were not free from the close surveillance maintained by the parish priest over the alms and goods of the cofradía (see Carbajal, 2023). Apparently, that of San Juan de la Laguna was the richest (Becerra, 2008: 160). Over time, the growth of their herds forced them to buy land that they would use for grazing. Likewise, the policy of grazing in open fields exposed their lands to occupation, giving rise to constant competition, a competition in which the Indians lost out.

The work of Becerra (2008: 393) affirms that the exponential growth of the population of La Laguna forced them to expand, which provoked the split and foundation of Buenavista and Moya. In principle, these foundations were viewed favorably by the inhabitants of the village, but their growth generated territorial disputes that were detrimental to the Indians. Perhaps the most significant example of this was the confrontation they had with José Zermeño de Anda over the appropriation of royal lands. At first they divided them, but the controversy went on for half a century and they ended up losing part of their lands. Hence, in 1757, the mayor and the principals of La Laguna requested the demarcation according to the boundaries established in their title deed dated 1672. The following year, in 1758, they initiated a lawsuit against Antonio Rincón Gallardo, the Indians of Buenavista and the town council to have half a league per wind recognized, but the result was not as expected. They did not obtain the missing lands, but lost part of the lands they owned (Becerra, 2008: 166).

Among the Indian towns, San Juan de la Laguna had the highest population and property density, so its lands were the most coveted, although it was not the only town in the municipality that had to use much of its strength and resources to conserve the land it needed for its subsistence. Unfortunately, many battles seem to have been lost, but the struggle continues. In this regard, Becerra's comment is very significant: "Finally, the Indian republic paid the price for a situation that characterized land ownership throughout the viceroyalty: the deficiency and ambiguity of land titles" (Becerra, 2008: 169).

By the second half of the century xviiiThe loss of territory that La Laguna had suffered was very important and derived from the ambiguity with which its boundaries were established, in contrast to those of its neighbors. The dispossession was obvious and, since the town was surrounded by other properties, there was no land to compensate them, so the commissioner suggested that it was the neighbors who should return at least part of their land. However, these proceedings did not achieve their objectives, nor did they prevent the neighbors from continuing to enter and seize the town's lands, as evidenced by the available archival documentation.3 This dispossession has continued to the present day. Carlos Gómez says:

Since the recognition of its legal basis in the 20th century, the xviito the following centuries xviii, xix and xxThe leaders of this community distinguished themselves by displaying a sustained pugnacity in countless lawsuits and legal proceedings in the courts; first, the colonial courts of Nueva Galicia and later of the state of Jalisco and even of the nation. There was an inveterate disagreement in this nucleus because it was not fully endowed with the lands established in the Royal Ordinances for the Indian towns (Gómez, 2006: 74).

It should be emphasized that, after centuries of historical dispossession, the people continue to claim the lands recognized in the viceregal era, because they represent a principle of unity among the ten neighborhoods that make up the town. Although they know that it is not feasible to recover them in their totality, they are convinced of the importance that these lands have in their identity, history and culture, and clamor for the conservation of the natural resources that are now in the process of depletion, since the space they have inhabited for generations has become more arid and lacking in vegetation.

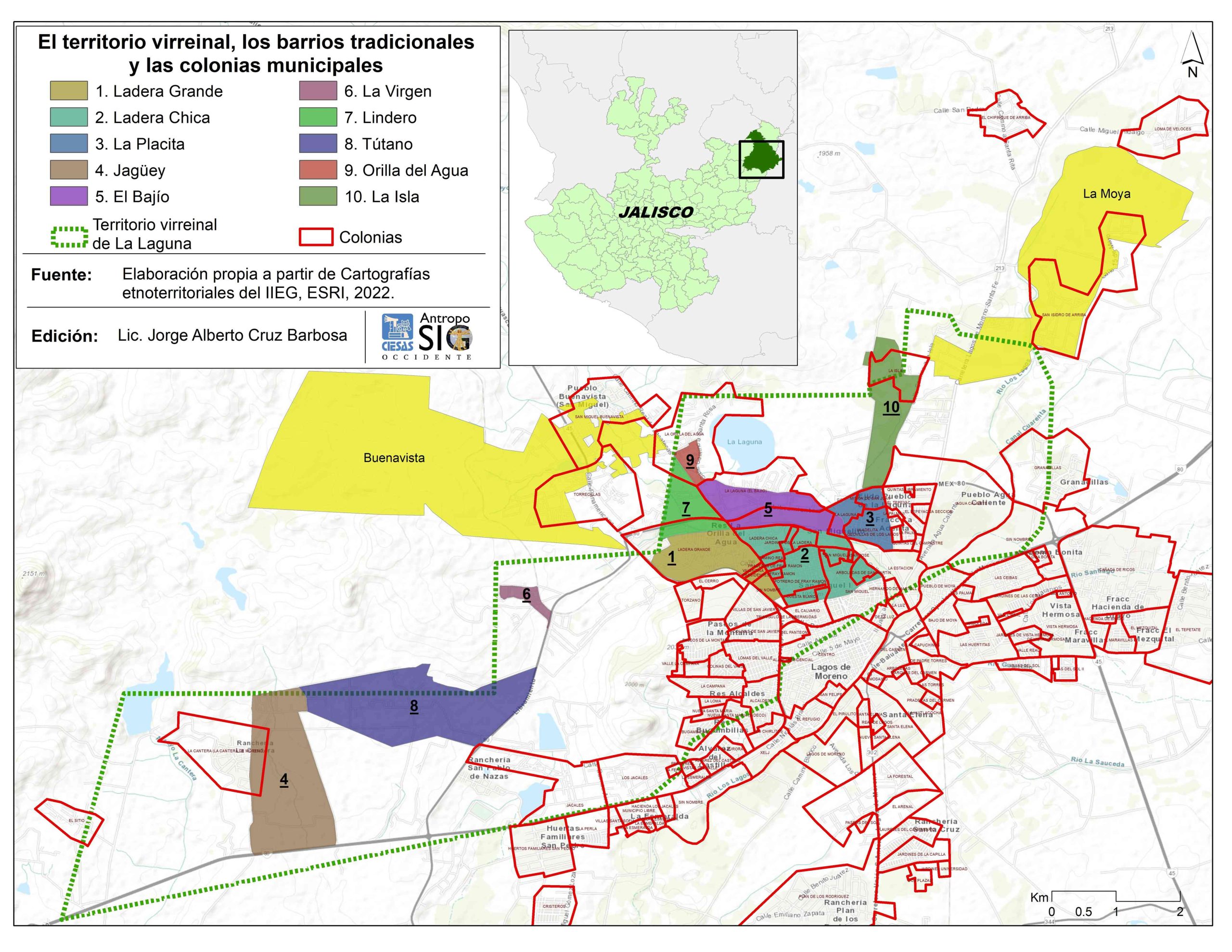

The people interviewed point out that, in the last few centuries, the xx and xxiThe process of dispossession was related to the refusal of the Agrarian Department to recognize the viceregal territory and the subsequent creation of an ejido and a community that regularized only a small part of the original lands, which divided the population and generated internal confrontations. At present, both agrarian units have been converted into small properties. They also recall that a good number of military men settled on village land during the second half of the last century. During this same period, the introduction of industry took place, which was installed on San Juan lands with the authorization of the municipal authorities. This stage has continued to the present and is characterized by the proliferation of factories and sugar mills throughout the territory, especially in the vicinity of the Libramiento Norte, the current industrial corridor. Finally, there is a third stage, still in progress, which has consisted of the construction of private subdivisions and social housing. In this way, the space has been occupied by external agents and a foreign population has been introduced, making the native people invisible or, at least, minimizing their presence. However, these families that self-identify as indigenous share a series of traditional practices that have been strengthened in recent years, through dialogue between the younger leaders -many of them women- and the elders.

The invitation to the feast and the arches' wake

For the Indian villages of Lagos de Moreno, the first activity of the year is the Convite a la Fiesta de Los Arcos. Thus, on January 1, a committee from Buenavista makes a parade through the neighboring towns, accompanied by music of reed flutes (with six holes) and drums. They visit the houses of the people in each neighborhood who will be responsible for assembling the arch with which they will make the pilgrimage to the Candelaria temple. They invite them to attend by giving them tobacco and distilled beverages, tequila and mezcal are the most common. This committee, currently composed of twenty elders and people knowledgeable about the tradition, is also responsible for buying the pulque that will be given to the pilgrims on January 24. They insist that they cover the cost of this drink with their own money, which represents an expense that is not always recognized by their neighbors. In addition, they are responsible for raising the funds for the fiesta that is celebrated on the same day and on February 2. The money raised is mainly invested in music and fireworks.4

The Convite Committee travels on foot and first visits Torrecillas, a neighborhood that belongs to Buenavista, but also builds its arch for pilgrimage. Then, they continue through Rancho de la Virgen, El Lindero, Ladera Grande, El Callejón, Ladera Chica, Moya, La Isla, El Bajío and, finally, La Orilla del Agua. All of these, except Moya -which is an independent town- and El Callejón, are neighborhoods of San Juan Bautista de la Laguna. San Juan has ten barrios, so in addition to those mentioned above, there are three more: Tútano, Jaguey and La Placita. Tútano and Jaguey do not usually make arches, although they attend the festival. Some people say that it may be because of the distance or because they are few people, but there is no doubt that they claim to be part of the town of San Juan. Others say that, in the past, these neighborhoods were part of the Rancho de la Virgen, which is why they are still represented in the arch of this place.

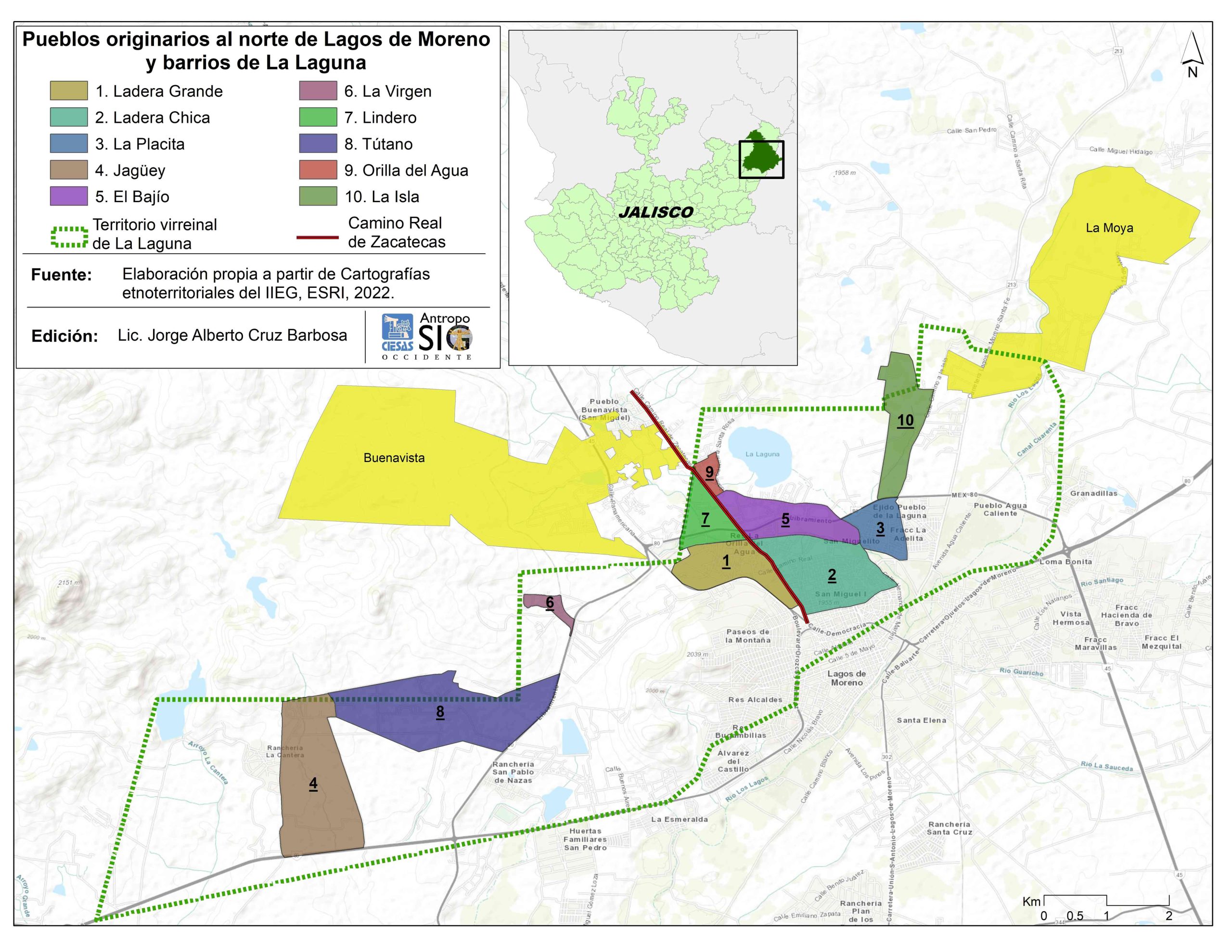

La Placita, La Adelita or El Pueblito is the old center of the Indian village of San Juan, so it is not considered a neighborhood at all, but something more, the heart of the town, it represents all the neighborhoods. There is the main temple that became a parish church in 2005. They do not usually build an arch there either, but they do participate in the celebration. El Callejón -known colloquially as El Calle- is a fragment of Lucas Nolasco Street located in the Ladera Grande neighborhood, but, above all, it refers to a group of neighbors who live there and who in recent years have claimed their independence to build their own arch and participate in the celebration in an autonomous manner. The distribution of the neighborhoods of San Juan Bautista de la Laguna is shown in Figure 1.

The town of Moya also began building its arch recently and joined the claim of unity and common origin in 2013. In 2024 they celebrated their twelfth participation. As is now customary they elaborated a large arch in blue with white in honor of the Immaculate Conception, patron saint of the town. The initiative to build an arch came from Alfredo Santos Martínez. He himself assures that the town has always been present in this celebration and remembers that the Santos family has been selling bread in the context of the celebration for more than thirty years. He also points out that since he was very young he felt the need to build an arch and, when he was older, he talked to Mrs. Estela Valadez, a neighbor of Buenavista. She talked about it with the members of the Convite Commission and put him in contact with Don Adolfo Rocha and Don José de Jesús Rocha, who has been part of this group since 1985. Alfredo had the intention of consolidating the union of Moya with the other two former Indian villages and he succeeded; in January 2013 the commission visited them for the first time to invite them to the pilgrimage.5

At first it was an extended family and other friendly families who participated, but the following year others joined in and proposed that a second arch be built, dedicated to the Lord of the Assumption, also patron saint of the town. They agreed that the arch of the Immaculate Conception would always be in the possession of the Santos family, as a reminder that they were the first to receive the invitation, although there are other families who help them.6 The arch of the Lord of the Assumption would change hands every year and would wear the colors white and red.7 Subsequently, they decided to make a small arch for the children, bearing the colors they attributed to the three towns: the yellow of Buenavista, the blue of La Laguna and the green of Moya.8 The largest arch, that of the Immaculate Conception, is carried by men, the one corresponding to the Lord of the Assumption is lighter and is carried by women. The smallest of the three is carried by children.

The case of Moya is a good example of the patterns that govern the distribution of positions in general and the way in which each group generates an iconographic discourse in the construction of its arches by reproducing a particular mystique. Sometimes these responsibilities remain in a single family, and at other times they rotate throughout the village or neighborhood. Both organizations are possible and are combined in the same collective. In addition, they usually have an alternative to introduce children and young people to these practices, which is achieved with great success. It is worth mentioning that, in some schools, the teachers organize themselves so that the children assemble their own bows.

The origin of the festival dates back to the founding of Buenavista. In order to become a town, it was necessary to first build a temple, since this was the basis for the measurement of land by reason of the town or legal estate of the viceregal era (see Castro Gutiérrez, 2016). They say that when the Virgin of Candelaria arrived for the first time, all the people of the town of San Juan gathered to escort her and lead her to her new residence in the temple of Buenavista. The arrival of the virgin some place it in the year 1692.9 Others say that the people of the town of Buenavista were laborers of a hacienda in San Miguel, where they had formed a brotherhood in the 1650s to take care of the virgin in that productive unit. Later they decided to found a town and the owner of the hacienda gave them the image as a gift.10 Both versions agree that the pilgrimage commemorates the arrival of the patron saint to the town, that upon arrival they were given pulque as a gift and that they had forgotten their differences derived from the split and decided to repeat this pilgrimage every year. Here it is appropriate to reproduce some words of don Jesús Rocha:

According to our beliefs, that is what the Blessed Virgin asked for when she arrived here, to the community of the town of San Miguel Buenavista. The one who brought her, that is what he explained to the ancestors. He told them that she wanted to be received with bows, with a band, with dance,11 music and a lot of people. That was when the invitation was made to all the neighborhoods, so that there would be people. Now, without lying to you, you will see and you will realize tomorrow that approximately two thousand people come on the pilgrimage, making the pilgrimage about five hundred meters long [calculates the length of the contingent] (Buenavista, January 23, 2024).

A third version of the origin of the festivity points out that an Indian from the town of Moya used to beg for alms carrying a pilgrim image of the Virgin of Candelaria, asking for money for the construction of the town and to celebrate the feast of the Virgin of Candelaria. This would take place since 1708, when the bishop of Nueva Galicia, Nicolás Carlos Gómez de Cervantes, authorized them to form a brotherhood. Thus, the Fiesta de los Arcos would represent the return of the commissioner of the confraternity to raise funds (Gómez Alonzo, n.d.).

As I have already mentioned, the Comité del Convite gives cigars and distillates to those in charge of the arcos. In the old days, they used to give them the tobacco they grew or collected, which they wrapped in a corn leaf. They remember that this "was prayed", that prayers were said so that it would fulfill its function effectively and would contribute to the alliance between the peoples. In reciprocity, the people in charge of the arches receive the committee with food and drink, they allow themselves to be entertained for a moment and continue on their way.

Activities resume on January 23, when neighborhoods and towns call their members to assemble, dress and watch over the arches. Some call people together at noon, but most gather in the evening. People will go to the meeting point, which will be the home of the person responsible for the arch, with sheets, blankets, fabrics and tarpaulins that will be used to dress the arch. A secretary or secretary will make an inventory of the garments provided by each person, so that they will be returned at the end of the celebration. The men will be in charge of shaping the structures of the arches so that, later, with the help of the women, they can dress and decorate them.

The structure of the arches is based on a beam with two forks that allow them to rest on the ground as legs. On this they form a rectangular frame that serves to fix a canvas, canvas, tablecloth or quilt with some religious or representative image of the collective that builds the artifact. In the upper corners of the rectangle they fix three curved rods forming concentric arcs. They usually use the branches of the mulberry tree for its flexibility. From the center of the base to the top of the arches they tie a thin rod or a long reed that ends in the form of a cross at the highest part. At the point where the rod converges with the upper pole of the frame, six reeds will radiate above the arches, three on the right side of the cross and three on the opposite side.

Once the structure is ready, they will proceed to "dress the arch". This consists of rolling and tying fabrics over the wood and reeds, preventing them from being exposed. Almost everything is put in place by tying it with ixtle or cords of different types. In the center of the largest arch, they place a small umbrella, formed with a semicircle of sticks or other materials, which will serve to protect the small picture of the Virgin of Candelaria that everyone must carry. On the cloth-covered structure, they tie oranges, cowbells or bells and flowers. As I have already indicated, on the frame they place an image with which the group that built the arch identifies itself. The reeds that radiate overhead will carry on the tips scarves or flags. About these there are several interpretations. Some say that there are six flags because each one of them corresponds to the neighborhoods of San Juan that participated from the beginning in the pilgrimage.12

Others say that the six flags and the central cross represent "the seven sorrows of the virgin" (Gómez Alonzo, n.d.: 11). Finally, on one side of the forks, inside the structure, they place horizontally two parallel crosspieces that will serve to form the platforms with which they will carry the arch on their shoulders. It is worth mentioning that, sometimes, some wooden or reed pieces are replaced by other metal ones, which are more stable and durable, but the shape of the arch does not change.

The construction of the arch keeps people busy late into the night. While the men work on the structure, busy women are seen preparing food for all who come to help. Stoves with pots of festive dishes invite the curious with their vapors. In El Lindero they cooked pozole, in Buenavista they made birria and in La Orilla del Agua they gave tamales. Everywhere they usually offer hot drinks (cinnamon infusion, punch or coffee) and the background music cheers up the attendees. Sometimes they share some distilled drinks. This previous congregation of collaborative work and festive preamble is known as "velar el arco". In the morning, in gratitude for the help, the landlord responsible for the arch and the families that assist him offer breakfast to all present. Traditionally they serve menudo, although they are not closed to innovation. After sharing the food, they get ready to go to the starting point of the pilgrimage.

The pilgrimage of the arches

The meeting point is in Cuesta Blanca, a colony located near the old gate of the town of Santa María de Los Lagos, where the territory of Santa María de Los Lagos ended and that of San Juan Bautista de la Laguna began. Some refer to this place as "La Puerta Blanca" (The White Gate). It is the point where the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro -a road considered Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations- ends. unesco- has been truncated by Democracia Street,13 as well as through the historic center of Lagos de Moreno. People say that, in the past, the tour started on the other side of Democracia Street, where the gate was originally located, but gradually they have moved to the north. First, to the Hotel Cuesta Real and, later, to the Sagrada Familia temple, recently built.

Camino Real is a dirt road, paved in fragments, which the city council has named Presidentes Street and heads northwest, marking the division of the neighborhoods of La Ladera Grande and La Ladera Chica, where it has been given the name of Chichimecas Street. Then, it crosses the railroad tracks and the Libramiento Norte that leads to San Luis Potosí and, from that place, it recovers its old title specifying its next destination: Camino Real de Zacatecas. From there it continues in the same direction tracing a straight line that runs along the western side of what was once the lagoon that gave its name to San Juan Bautista and leads to the town of Buenavista,14 destination of all the pilgrims who gathered at the opposite end of the road.

The appointment was at eleven o'clock in the morning, at which time the arches began to arrive and the contingents took their places. The hosts from Buenavista always lead the way, followed by those from Ladera Chica, Torrecillas, Rancho de la Virgen and La Orilla del Agua. Behind the latter, the image of the Virgin of Candelaria, which had been transported to this point by the parish priest of La Laguna and a group of men from Buenavista in a red pick-up truck, went on pilgrimage. The image of the virgin was followed by El Lindero, El Callejón, La Isla, El Bajío and Moya, the last to join the pilgrimage. At first it was said that Ladera Grande would not participate, as they had been sanctioned for having caused a brawl the previous year, but the arch was present and made the pilgrimage behind El Lindero.15 Behind all of them are the charros on horseback, young and old, men and women, some with their children. These are riders who live mainly in Torrecillas and Buenavista.

The arches require four porters who support the ends of the bows on their shoulders. At the highest part of the arch they tie two ropes, one will fall from the front and the other from the back. At each end a person helps to balance the arch, to prevent the wind from knocking it down, and assists in overcoming obstacles. In addition, they must have the services of a garrotero, a pilgrim who carries a long reed with which he lifts the cables that hang from the poles and allows the structures to pass. Let's remember that each group usually carries more than one arch and a crew that will accompany and assist the cargadores when necessary. Some neighborhoods hire a band to play exclusively for them and animate the entire route, other bands are included in the pilgrimage and offer their services by the hour or by song.

The road is long, especially for those who carry the bows on their backs, and the intense sunlight does not make it any easier. The movement is slow and solemn. The rocket booms are constant since the night of the vigil and accompany each step of the pilgrimage. The band music cheers the assistants and, at the end, makes them break with formality and invites the bearers to dance. The bands are made up of tarola, tambora, metal güiro, clarinet, trumpets, trombones and tuba. They play lively music, to which the younger bearers jump up and down while spinning the bow. The elders disapprove of breaking the solemnity in this way, not only because it detracts from the seriousness of the act, but also because many times the bows break and the images of the virgin end up on the ground. Apparently, the dance of the arch is a new practice, but it is here to stay, in spite of the strong criticism against it.

In Buenavista, the bell ringer waited attentively in the tower of the temple and the people gathered in the square in front, where food stands and games for children were set up. Upon arriving in town, the bells began to ring, the arches cleared the way for the virgin on the entrance street and shook as she passed in front of them. The bearers of the patron saint placed her on an altar they had improvised in front of the church. The people shouted vivas in her honor and applauded enthusiastically, the priests encouraged these festive expressions and invited the people to sing a song in homage to Santa María. At the conclusion of the brief tune, the bows were presented, one by one, before the altar. There the cargadores bowed slightly in reverence, uncovered their heads and knelt in front of the virgin. The charros did not get off their horses nor did they kneel, they only took off their hats. By then the clock was striking four o'clock in the afternoon, five hours had passed since they had gathered at the starting point, but the pilgrimage had begun around one o'clock.

After passing through the altar, each of the arches took its place on the perimeter of the square. For this, they follow the same order of the route and that corresponds to the turns to march back home. Each group knew very well which was the place that corresponded to them. Then the mass began, officiated by the parish priest of La Laguna and his auxiliary. It concluded with a blessing for all the families of the towns: "To these families so in need of God's blessing" and "disintegrated and incomplete because of the disappeared". There is no space to delve into this, but the situation of violence that afflicts them is well known. Afterwards, the parish priest took the image of the Virgin in his hands and carried it to the place where each of the arches was located. There he placed the statuette above his head and the groups bowed. This concluded the participation of the priests.

After the mass and blessing, the Buenavista committee gave twenty liters of pulque and a pack of cigars to each group. Jesús Rocha, one of the people responsible for this gift, said: "It is our tradition and many people call it La Fiesta del Pulque. We are proud that our ancestors have left us this jewel, right, because we follow it [...]".sicWe are rescuing until God gives us license. There are also families from Buenavista who gather to offer food to visitors free of charge. The traditional food of this fiesta is mole with rice, which can be made with turkey or chicken, although the former is less and less frequent.16 The dish is accompanied with corn tortillas and orejona or romaine lettuce leaves, both of which are used as spoons, since it is not common to use cutlery to eat mole. The people of Buenavista see these gifts as a way to reciprocate the gestures of hospitality that began with the feast and that, with respect to Buenavista, have their ultimate expression in the farewell of the arches.

The conviviality in Buenavista lasted for a few hours, during which people danced to the band music and drank pulque happily. Visitors know they must leave before dark to walk home. Then, the arches dance with more frequency and energy. In the village a dry law has been imposed, no alcoholic beverages are sold, only pulque is supposed to be allowed, but many provided themselves in advance. Each of the archers must be dismissed individually and is led out of the village by the hosts and the brass band. It is the last gesture of reciprocity by Buenavista during the festival. Then, everyone will take the road home. In the meantime, the townspeople will prepare for a dance that will last until the early hours of the morning.

In La Laguna and Moya the pilgrims will be welcomed by family and friends who will offer them a dinner. After recovering their strength, they will have to undress the arches. Everyone helps to remove the fabrics and dismantle them. With list in hand, the secretary will return the garments to their owners. At that moment, the person who will be in charge of the arch next year is usually appointed. The new person in charge will receive from the hands of the outgoing person the picture of the Virgin of Candelaria that was in the center of the arch. With this act the transmission of the commitment is consummated.

This concludes the celebration of the arches, but it only marks the beginning of the novenario that will conclude on February 2 with the Fiesta de la Luz or Fiesta de las Candelas, patronal feast in honor of the Virgin of Candelaria, patron saint of Buenavista. Undoubtedly it is also an important day for the people of La Laguna and Moya, but for everyone it is especially significant that moment when they assemble the arches, go on pilgrimage, share pulques and recall the reconciliation that ended the confrontation produced by the fragmentation of the original town.

Concluding remarks: reclaiming the indigenous past

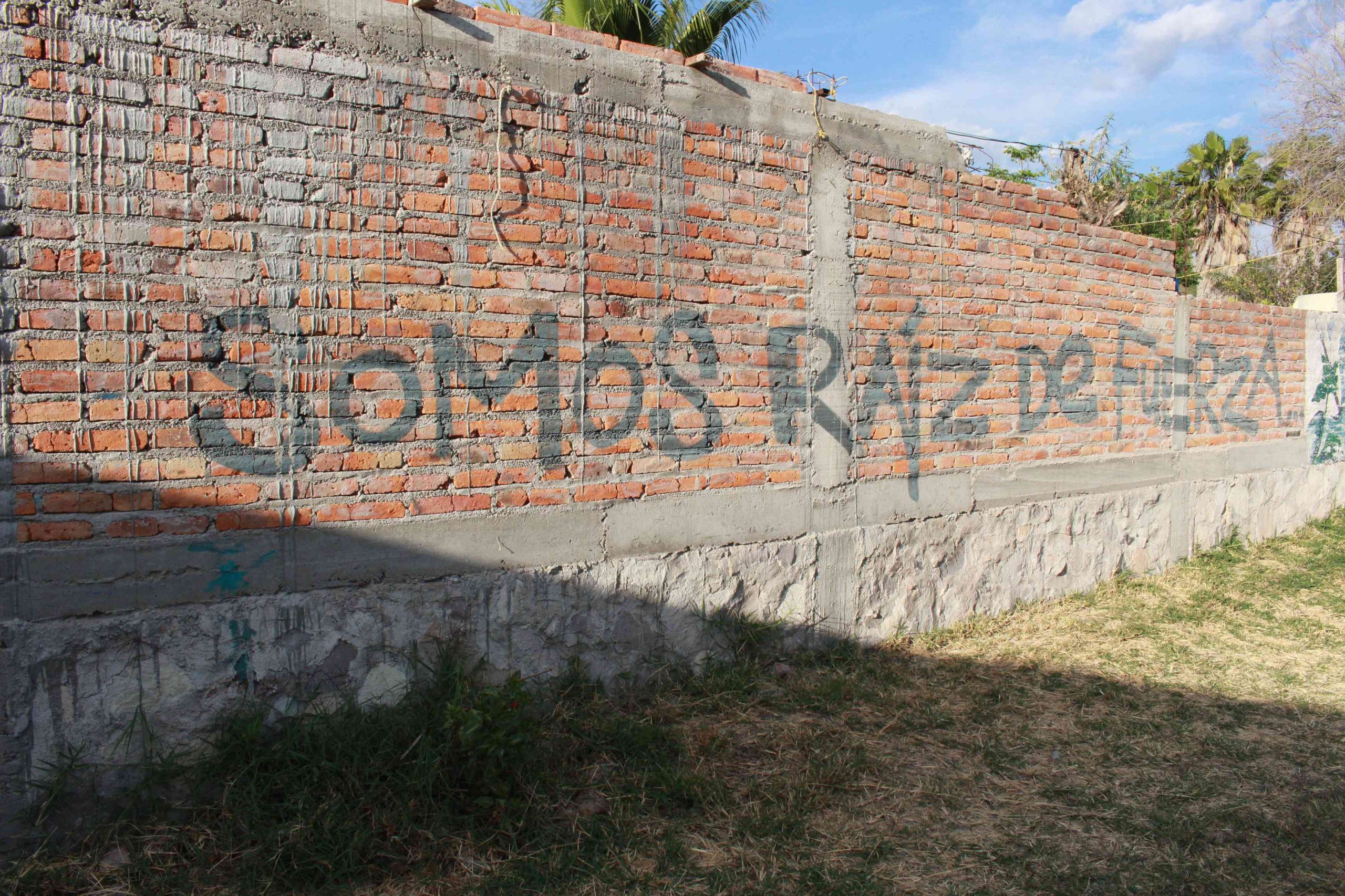

The people interviewed at the festival insisted that carrying the arches on their shoulders is hard and painful work, but they assured that it is endured thanks to the feeling of rootedness, pride in identity, affection for tradition and "the strength that characterizes the men who have dedicated themselves, for generations, to the manufacture of bricks".17 This last sentence highlights the predominant role that men have played in the reproduction of this celebration, which has recently been strengthened by the enthusiastic participation of women and children. Apparently, not many years ago, women accompanied the men and occupied a secondary place. They point out that they went to take care of them, to make sure that they did not fight, that they did not hurt them and that they returned home safe and sound, since incidents due to excessive consumption of intoxicating beverages were very common. It appears that his intervention has led to a significant reduction in these incidents.

Moreover, they are convinced that "the feast is strength", a phrase that has given title to one of the few descriptions that have been made about La Fiesta de los Arcos (Facio, 2021). They think that this ritual is a way to fight for the vindication of their identity as native peoples, for the respect of their rights and the defense of their territory. The construction of the arches and the festival is considered an act of resistance (see Facio, 2021; Guzmán, 2024).

The struggle for the territory has resumed with renewed vigor following the mobilizations that began in 2018 to prevent the construction of a gas pipeline by the Gas Natural company on the lands of San Juan de la Laguna. The complainants pointed out that this project did not have a land use change authorization, nor environmental, social and risk impact studies, that the natives had not been consulted about the project, its objectives and beneficiaries, among other things. They wanted a dialogue to be established and their right to consultation as an indigenous people to be respected. On May 13, 2019, a protest demonstration was held against the works, which was repressed, taking things further. Five people were detained by the municipal authorities and the people of San Juan mobilized and took over the municipal presidency to request their release. The repression went on for some time, and several of the activists claim that they were visited by people from the Jalisco Prosecutor's Office to carry out searches in a threatening attitude. Currently, the camp where they set up to prevent the construction work continues to be an important meeting point.

The Institute of Statistical Information and Geography (iieg) has calculated, in a study of ethnoterritory and social cartography, that the village of La Laguna eventually covered an area of 4,847 hectares.18 These lands have now been converted into small properties and recently La Laguna has been divided into colonies of the city of Lagos de Moreno, a territorial scheme that overlaps the traditional system in which the town of San Juan de la Laguna thinks of itself as a space of sociocultural interaction among the ten neighborhoods that compose it and that are distributed throughout the territory they acquired by grants and purchases during the viceregal period. The same can be said for Buenavista and Moya. In turn, the three towns constitute a unit, based on their common past, traditions and important kinship ties.

In these lands, mainly in the vicinity of the lagoon, important concessions have been granted to industries that have significantly affected the ecosystem, depleting and contaminating the water. In addition, the old village has promoted the introduction of new inhabitants in an attempt to dilute the indigenous profile of the population. Their lands are no longer recognized as communal property, nor are their traditional authorities considered as mediators in municipal or state politics. This blurs their existence as native peoples, making them invisible as societies and subjects of law -they claim-. In this regard, the State Human Rights Commission issued a recommendation on the case for "violation of the rights to legality and legal security, to peaceful demonstration, to personal freedom, to the rights of native peoples and indigenous communities, as well as to development, cultural heritage and a healthy and balanced environment, of the inhabitants of San Juan Bautista de la Laguna, in the municipality of Lagos de Moreno".19 The first recommendation is that the people of San Juan de la Laguna be incorporated into the Register of Indigenous Communities and Localities of the state. Then, it talks about the reparation of damages to the indigenous community, the suspension of licenses granted to various companies without consultation, the restoration of the ecosystem and that this area be declared an ecological reserve, among many others. Recognition as an indigenous people and their territorial rights are central to this recommendation.

The truth is that the residential separation between the republic of Indians and that of Spaniards, which was intended to promote evangelization and ensure labor for the town, is still in force. In the original villages there are the brick makers and bricklayers who still build the city. In addition, there are the plumbers, electricians, mechanics and other trades. There are also domestic helpers, employees in restaurants, hotels, bars and others in the service sector. They are also frequently employed as workers in local industry, which often affects the environment in which they live and with whose productive strategies they often disagree.

The transformation of the environment, derived from overexploitation, has resulted in the displacement of agricultural activities, placing the original inhabitants in the lowest strata of the local economy, a level to which many others from abroad have been added and who have been introduced into their space through the purchase of land and the construction of low-income housing. Many of them are foreign laborers who work in the industries that have established themselves in the vicinity of the Libramiento Norte industrial corridor.

However, this has not prevented the families of the original peoples from continuing to claim to be descendants of those who made up the ancient republic of Indians, even though they are told that they are now only colonies of the municipal capital. Thus, while the contemporary original peoples are denied, the past peoples who inhabited these lands are vindicated in the official discourse. Recently this paradox has had a monumental expression. In February 2024, the municipality inaugurated a sculpture in honor of Xiconaqui and Custique, indigenous leaders of the region who opposed the European occupation in the 20th century. xviwhose "original tribes" are represented in the coat of arms of the city by two mounds with a pennant on top symbolizing the triumph of the Spanish crown. On the border surrounding the coat of arms, one can read the inscription "Adversus populos Xiconaqui et Custique fortitudo"which translates as "Fortress against the adverse peoples of Xiconaqui and Custique". A vindication of an indigenous past or of their reduction?

It should be added that in April 2024, by popular initiative, the monument began to be surrounded by search cards of missing persons in the municipality, now it is thought of as "the Glorieta de los Desaparecidos" (Roundabout of the Disappeared). Resignification of a past that does not seem to be present for some. For their part, the families that descend from the indigenous societies that made up the villages north of the town of Santa María de los Lagos do not see in the public sculpture a tribute, but rather the unnecessary waste of public resources to avoid addressing the real problems of these populations. Their demands do not imply the recognition of the ownership of the space they have occupied since the foundation of the towns, but respect for the environment in which they have lived, the possibility of making decisions in the face of overexploitation, but, above all, to be recognized as native peoples and to keep their identity alive. This is the struggle they maintain in the tenacious reproduction of their traditional life, in which the arches are past, present and future.

Bibliography

Aguilar Alcaide, José Fernando (2004). La hacienda Ciénega de Mata de los Rincón Gallardo: un modelo excepcional de latifundio novohispano durante los siglos xvii and xviii. Guadalajara: UdeG/csic.

Becerra Jiménez, Celina (2008). Gobierno, justicia e instituciones en la Nueva Galicia. La alcaldía mayor de Santa María de los Lagos 1563-1750. Guadalajara: UdeG.

Berthe, Jean-Pierre, Thomas Calvo y Águeda Jiménez Pelayo (2000). Sociedad en construcción. La Nueva Galicia según las visitas de oidores (1606-1616). Guadalajara: UdeG/cemca.

Carbajal López, David (ed.) (2023). Dos iglesias de Lagos hacia 1729: La Parroquia y Moya. Guadalajara: Amate.

Castro Gutiérrez, Felipe (2016). “Los ires y devenires del fundo legal de los pueblos indios”, en María del Pilar Martínez López Cano (coord.). De la historia económica a la historia social y cultural. México: iih-unam, pp. 69-104.

Fábregas, Andrés (1986). La formación histórica de una región: Los Altos de Jalisco. México: ciesas.

Facio, Lilith (2021). La fiesta hace la fuerza. La Fiesta de los Arcos como práctica de comunalidad en el pueblo indígena de San Juan de la Laguna. Puebla: Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco/pacmyc.

Gerhard, Peter (1996 [1982]). La frontera norte de la Nueva España. México: iih-unam.

Gómez Alonso, José Israel (s. f.). Historia de San Miguel de Buenavista: 331 años de su fundación. Lagos de Moreno: Ayuntamiento de Lagos de Moreno/H. Junta Patriótica Pedro Moreno/Archivo Histórico de Lagos de Moreno.

Gómez Mata, Carlos (2006). Lagos indio. Lagos de Moreno: UdeG.

Guzmán Orozco, Carmen (2024) “El trabajo de las mujeres en la defensa del territorio en el pueblo indígena chichimeca de San Juan Bautista de la Laguna y su movimiento de resistencia. Una lectura desde el género, las relaciones de género y lo común”. Tesis de la Maestría en Desarrollo Rural. México: uam-Xochimilco.

Mota y Escobar, Alonso de la (1940 [1605]). Descripción geográfica de los reinos de Nueva Galicia, Nueva Vizcaya y Nuevo León. México: Editorial Pedro Robredo.

Hector Medina Miranda is a research professor at ciesas and member of the National System of Researchers., level ii. He holds a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Salamanca; a master's degree in the same discipline with a specialization in Ethnology from the University of Salamanca. unamdegree in Social Anthropology from the enah. He has conducted research on social organization, rituals and mythology. wixaritari. In recent years his studies have focused on the analysis of the territorialities of these peoples from an anthropological and historical perspective and has ventured into the study of other indigenous societies of Jalisco. In addition, he has developed projects on livestock stereotypes in Spain and Mexico, as well as bullfighting rituals and livestock traditions on both sides of the Atlantic.