Devotions in transit: an ethnographic approach to the Soconusco Isthmus-Costa migratory circuit.

- Blanca Mónica Marín Valadez

- ― see biodata

Devotions in transit: an ethnographic approach to the Soconusco Isthmus-Costa migratory circuit.

Receipt: February 29, 2024

Acceptance: November 5, 2024

Dedicated to all the people who

have lost their lives in the process of

mobility, in particular to those who have

40 migrants who perished at the border checkpoint of

Ciudad Juárez in March 2023 and to meja.

Abstract

The migration phenomenon in the Soconusco region, Chiapas, reflects a melting pot of human experiences crossed by social, economic and cultural challenges. This border region, with a historical migratory mobility, has stood out for receiving thousands of migrants from Central America, South America, Africa and Asia seeking to reach the United States or to settle in different regions of Mexico, who face various obstacles along the way. The purpose of this paper is to show the role played by religious representations, not only as a manifestation of faith, but also as symbolic expressions that allow subjects in migratory mobility to reaffirm their social meanings, build communities of support and mitigate the challenges derived from their conditions of vulnerability.

worship in transit: an ethnographic approach to the migrant circuit from soconusco to istmo-costa

Soconusco, Chiapas, is a melting pot of migrant experiences characterized by social, economic, and cultural challenges. This border region, with its history of human mobility, has received thousands of migrants from Central and South America, Africa, and Asia who seek to reach the United States or settle in different regions of Mexico. During their journey, these migrants face a range of obstacles. This article reveals the role of religious icons in this region, as an expression of faith but also as symbols that allow migrants to reaffirm their social beliefs, build supportive communities, and confront the challenges associated with vulnerability.

Key words: human mobility, migrant circuit, religious expressions, vulnerability, agency.

Work organization

The paper is divided into five sections: the first one summarizes the history of the region and its demographic composition based on the processes of mobility; the second one discusses the importance of the migrant subject, not only as a vulnerable subject, but also as a subject in control of his or her mobility processes who, in addition, participates in cultural circulation; the third, fourth and fifth sections present brief ethnographic descriptions that allow us to recognize the challenges of migratory mobility and the way in which religious expressions operate. Finally, a conclusion is drawn about the importance of these devotions in transit in migratory mobility.

Soconusco Isthmus-Costa

Soconusco is an important region on Mexico's southwestern border with Guatemala and the Pacific Ocean, which has gone through several political processes that, in the words of Justus Fenner, ended with a neutrality imposed between 1824 and 1842.1 when the population was submerged in various uncertainties due to the lack of legitimate authorities capable of establishing order. In 1842, Chiapas was annexed to Mexico through a decree issued by General Antonio López de Santa Anna; the annexation was formalized through the Mariscal-Herrera treaty in 1882 (Fenner, 2019). The establishment of the borders of Soconusco represented a new stage for the municipalities that make up the region,2 According to María Elena Tovar, in her article entitled "Extranjeros en el Soconusco" (2000), the federal government launched a political colonization campaign that consisted of attracting European and Catholic immigrants who shared the values of freedom, progress and democracy in order to achieve the ideals of modernity, since the indigenous populations of the Soconusco region were not the only ones to be affected by the colonization campaign.3 represented an obstacle for these purposes.

With a prosperous tropical climate for agricultural activities and political conditions that favored land acquisition, groups of foreigners arrived in Soconusco with different designs and conditions. As Tovar points out, the Germans,4 Americans and Japanese arrived in the region supported by colonization policies; the Kanakas and Guatemalans, for labor in agricultural activities, and the Chinese, for the construction of railroads (2000: 30). From the logic of the farm model, agricultural production grew exponentially, thanks also to the introduction of new products such as coffee, rice and sesame. Each group had a very clear role to play, which generated significant conditions of exploitation for the groups of laborers working on the farms.5 However, it is necessary to recognize the importance of these groups as part of the cultural diversity of a region that had been inhabited by the Mam ethnic group, whose identity was significantly reduced after the Mexicanization process that began in 1930 (Fuentes and Corzo de los Santos, 2023).

In addition to this diversity, in the last decade the presence of Afro-Mexican groups in the municipalities of Acapetahua and Acacoyagua has been institutionally recognized, despite the few historical and ethnographic data that can shed light on their arrival in the region. Therefore, it is unavoidable to point out the historicity and importance of migratory mobility in the Soconusco, a door that opens and closes, a cultural space that has brought together multiple ways of living and feeling the border, and that has become a region that is nourished by the processes of migratory mobility that leave traces in the cultural and historical memory of those who inhabit it.

The Soconusco, in addition to being a place of passage, also became a place of destination, since job offers have represented important sources of income -despite precariousness- for migrants of Central American origin, who have been integrated into various economic activities and have woven cross-border and transnational relationships between the Soconusco and their countries of origin (Rivera, 2014).

Soconusco Istmo-Costa Migratory Circuit

Migratory mobility in Soconusco has a long history and has occurred in different forms; however, in recent decades, migratory transit through the region has become much more visible due to the multiple forms of migrants' organization to safeguard themselves during their journey, which, at the same time, has become more complex due to the political, economic and even environmental situations that have affected social dynamics; For example, the impact of Hurricane Stan, which hit southeastern Mexico in October 2005, profoundly disrupted daily life in the Soconusco and Istmo-Costa regions, because, in addition to human losses, the destruction of sources of work and infrastructure was considerable; likewise, the migratory journey acquired new challenges. According to Jaime Rivas Castillo, in his article "Victims nothing more? Central American migrants in Soconusco, Chiapas" (2011), the contingency caused by Hurricane Stan moved the railroad track along which the "Bestia" (the Beast) travels.6 from the municipality of Ciudad Hidalgo, which is located on the border with Guatemala, to the municipality of Arriaga,7 Chiapas; that is to say, it was traveled 274 kilometers from the border.

From this disposition, the Soconusco and Isthmus-Costa regions were articulated and brought new challenges for migrants in transit because the conditions of vulnerability during the journey were accentuated. However, as Rivas Castillo points out in the aforementioned text, it is not possible to reduce migrants to vulnerable and passive beings in their mobility process, but rather to observe the mechanisms and strategies they develop to face the challenges they encounter during their journey, such as detentions,8 extortions by migratory agents and criminal groups, sexual violations, economic extortions, robberies, persecutions, kidnappings, among others. The author continues: "migrants are also creative individuals who, despite the constraints, are protagonists of their migratory processes" (Rivas, 2011: 9). For this reason, he proposes the construction of new lines of analysis that avoid totalizing migrants as subjects marked only by their vulnerability and recognize the strategies and resources they design and have at their disposal to face risks. For my part, I would add that migrants are cultural subjects and that these referents allow them to symbolically express their desires, which, I would dare to point out, even mitigate the vicissitudes encountered during their journey.

Soconusco and the Isthmo-Costa have become a migratory circuit through which people, goods, stories and symbolic expressions, such as religious representations, circulate. I agree with Renée de la Torre and Patricia Arias (2017), in the introduction to the book. Religiosidades trasplantadas. Recomposiciones religiosas en nuevos escenarios transnacionaleswith its point that the manifestation of the sacred in migratory mobility recomposes the social fractures that are produced by the diverse practices of human mobility:

Migration generates the need to reconcile times and distances between two homes: the one of origin and the one of destination. What was left and what was arrived at. And it is here where religiosity becomes a very important resource of migration, a resource to reconnect dispersed territories, to reconnect multicultural identities, to reconnect networks of countrymen and families dispersed in space, to reconnect memories with experiences of the present and utopias (De la Torre and Arias, 2017:18).

In relation to the points made by both authors, the following three ethnographic descriptions present the crossroads between the religious phenomenon and migratory mobility in different contexts and circumstances in the Soconusco region, a scenario marked, from its beginnings, by multiple migratory dynamics.

Exodus and prayer: conflicts and convergences in one of the caravans of the Soconusco Istmo-Costa migratory circuit.

At the end of October 2021, a migrant caravan of close to four thousand people of different nationalities departed from Tapachula. It was known in the media as the "caravan of pregnant women and children" and, in fact, it was one of the caravans that has stood out for the diversity of conditions: pregnant women, men and women of adult age who transited the territory with their families, some of them extended, as well as a large group of the community. lgbttiq+All of them were accompanied by international non-governmental organizations, as well as by different security agencies, such as the Federal and State Police, and the Beta group.9

The organization of this migrant caravan occurred after having been waiting for a response from the immigration authorities in Tapachula, where some had been detained for up to a year. Several had met Juan, a lawyer, activist and religious leader in favor of human rights who maintains a shelter, where, in addition to offering them lodging and some food, he prayed with them; the experience of other caravans inspired several migrants to ask for Juan's help to set out on the road to Mexico City, where their immigration status would supposedly be resolved, and then begin their journey to the United States. In this way, the group of the "caravan of pregnant women and children" left Tapachula in mid-October, stopping in some towns where they rested, ate and refreshed themselves. Most of the caravan stops in the Soconusco Istmo-Costa circuit have been set in the following municipalities: Huehuetán, Huixtla, Villa Comaltitlán Escuintla, Acacoyagua, Ulapa, Mapastepec, Pijijiapan, Tonalá and Arriaga.10 One of the problems faced by the population was the hot weather, which can reach up to 45 degrees Celsius, which determined the pace of the walk, as pregnant women, some elderly people and children could not walk at the pace of the other members.

As the caravan approached the town of Escuintla,11 the dynamics of the place was transformed: a day before the arrival, at the entrance of the village, some vans of the National Institute of Migration (Instituto Nacional de Migración (imm) and tents were set up for members of the state and federal police in the vicinity of the coastal highway. Their presence caused some tension and uncertainty among the population, which also became polarized after the arrival of the caravan. The migrants settled in the central park, where there are basketball courts, a parking lot, several planters and a large auditorium. The organization Doctors without Borders placed its team to treat the health problems that arose during the journey, especially the most vulnerable members, such as children, the elderly and pregnant women, who suffered from dehydration, heat stroke and blisters on the soles of their feet.

The staff of Médecins Sans Frontières, overwhelmed by the multiple cases, incorporated into their team local people who volunteered to help, some of them with basic training in nursing. Another institution that tried to attend to the health problems was the Beta group; however, some caravan members were somewhat afraid to approach them because they perceived them as agents of the im and feared arrest.

It is important to note that the inhabitants of the region are generally considered xenophobic; this is undoubtedly a serious error that builds stereotypes of the populations that belong to this circuit, in which, of course, there are locals who strongly reject the arrival of these populations to their municipalities, but there is also a large population that has shown supportive and empathetic attitudes.

For the organization of the caravan, some responsibilities were delegated to different members of the caravan, in order to avoid the infiltration of external agents that could create conflicts. One of the most vulnerable sectors was the community lgbttiq+The migrants, who were rebuked by other sectors of the caravan, pointing to them as alcoholics, "mariguanos", scandalous and setting a bad example to the children, seemed to be an expression of the homophobia of some of the migrants, since members of the community lgbttiq+ had collectively accepted the agreements not to drink during the tour.

One problem that was attended to by the caravan guards and which alarmed the population was the following: they identified a presumed trafficker within the organization, who had identified himself as Guatemalan, but his behavior generated some suspicions when, with his cell phone, he "discreetly" began to take pictures of the women resting in the auditorium. When one of the security guards noticed this, he alerted the other members of security, who checked him and found that he was carrying his credential from the National Electoral Institute (ine) with address in Zacatecas; the migrants captured him and presented him to Juan, who asked some lookouts to safeguard the young man's integrity and take him to the local authorities. In this situation, some people had anxiety crises because they were frightened by the fear of being confronted by criminal groups; some women even began to cry, especially the mothers of those who had been photographed. For their part, some men, annoyed, waited outside the town hall to confront the man; however, at that moment, Juan took a megaphone and summoned the migrants to the center of the park and recited the following words:

Migrant brothers and sisters, you are God's chosen people. Let us pray and thank our Lord Jesus Christ for the protection he is giving us in this journey and because we have the right to seek a better life for our children, and no one can stop us. My God, thank you, because you are the only one who can decide about the future of our migrant brothers and sisters! Give us strength, because this is not a migrant caravan, this is a migrant exodus; that is why our lives are in the hands of our Lord Jesus, and long live Honduras, long live Guatemala, long live El Salvador, long live Venezuela!

As John spoke, the congregants began to shout and clap their hands; the people repeated John's words in unison, men and women held hands, some began to pray in silence, others bowed and wiped their tears, embraced each other and asked Jesus to reach their destination safely.

Following the reflections of Erika Valenzuela and Olga Odgers, in the article "Usos sociales de la religión como recurso ante la violencia: católicos, evangélicos y testigos de Jehová en Tijuana, México" (2014), we agree that religious systems are composed of a web of meanings that operate in the decision making of individuals. The authors take up Lester Kurtz's perspective to analyze the elements present in these systems:

[...] we take up Kurtz's proposal, who distinguishes three closely related spheres or dimensions: beliefs are legitimized and embodied through rituals; in turn, rituals and beliefs are regulated by more or less institutionalized bodies. And such institutions fulfill the function of controlling changes and preserving the ideas and practices that constitute the core of belief systems, around which a community of believers is built (Kurtz, 2007, in Valenzuela and Odgers, 2014: 15).

The complexity of the journey, the siege by security agencies, the health conditions of the members of the organization, and the homophobic remarks made by the community lgbttiq+ The fact that the young man who was taking photographs was a constant source of fractures within the caravan, and the incident with the young man who was taking photographs increased the tension. Nevertheless, the prayer that Juan recited through the megaphone managed to bring together all the participants -despite the diversity in terms of creeds and identities- and restore the social fabric. This is why symbolic expressions based on religious representations play an important role in strengthening communities in transit; they are also preponderant in facing conditions of risk and vulnerability individually and collectively, as they not only connect the migrant community when social ties are weakened, but also constitute an intangible resource to face diverse challenges, becoming a significant element in the recomposition of fractured fabrics.

Migration processes produce and recreate different communities permeated by the conditions of mobility and the belief systems involved. The following reflection deals with the cross-border dynamics of the cult of San Simón in the municipality of Escuintla, Chiapas.

Saint Simon, the itinerant saint

In Soconusco there are multiple religious expressions that make up the cultural scenario of the region, and one of them has to do with Saint Simon, a saint of Guatemalan origin who does not belong to the Catholic pantheon, whose cult has flourished in different Central American countries, in Mexico and in the United States. Its plasticity in terms of its symbolic content has been fully adjusted to the processes of migratory mobility, as it functions in this context as a protective saint and a symbolic agent of deportation: there are those who make offerings to him to request the deportation of a loved one who forgot his affections upon arrival in the United States. In the Soconusco region his cult is practiced in two main scenarios: one of them is in bars and cantinas, and the other in Mesas Sagradas, where Saint Simon is the patron saint and different practices of white and black witchcraft are carried out.

One of its characteristics is related to its ambivalence, since the saint is asked to perform works to cure a person or to destroy him or her; to make someone fall in love or to humiliate and dominate him or her; to "raise" a business or to make it fail. The arrival of Saint Simon to the region has been produced thanks to cross-border mobility; in that sense, it is a religious expression that has circulated constantly between Guatemala and Soconusco and has even produced organizations that visit its two main temples in Guatemala: one of them, in San Andrés Itzapa, Chimaltenango, and the other in Zunil, Quetzaltenango. Some researchers of the cult in Guatemala have exposed its deep relationship with indigenous groups, although in other contexts its devotees do not belong to these social sectors. San Simón the mestizo, the ladino, is the devotion that has been incorporated with exponential force in Soconusco, as well as in other regions of the southern border of Mexico and even in the United States.

The following is a brief outline of the studies that have been carried out on this religious figure.

A sketch of the cult of St. Simon

San Simón has been consolidated within the scenario of popular religiosities. In that sense, there have arisen diverse and heated debates among some specialists in the subject who maintain that this saint is actually Maximón, that is, the Rilaj Mam, a nawal of the Mayan cosmovision that is venerated through a complex system of brotherhoods in the Tz'utujil village of Santiago Atitlán, which belongs to the department of Sololá. There he is represented with a palo pito trunk covered by different textiles of the region and a Texan hat; he wears a mask with an orifice in the lower part, where they place intoxicating drinks, cigars and cigars (Mendelson, 1965; Vallejo, 2005). The other representation is that of a white man with a mustache and Texan hat who is seated on a chair; in one hand he carries a staff and in the other, a Guatemalan flag or a "borolita" of guaro; this image is named as Saint Simon and is venerated outside Santiago Atitlán.

In San Andrés Itzapa, Chimaltenango, a temple was built in his honor, where the image of St. Jude Thaddeus is also found, and the brotherhood in charge of protecting the enclosure is named after the saint (Debroy, 2003). In Zunil, the image differs slightly: there he appears without a mustache and with dark glasses; his cult is guarded by the brotherhood of the Holy Cross, and the prayer dedicated to the saint is related to the myth of origin that is reproduced in that locality, where the figure of the Indian Philip stands out, who had an encounter with St. Simon thanks to his generosity and the saint is disassociated from Judas Iscariot. Regarding this topic, a discussion has been generated about the legitimacy of the cult, pointing out that the Maximón venerated in Santiago Atitlán and the Saint Simon venerated in Chimaltenango are two different personalities; while others affirm that both are the same deity and that their veneration was born in the Tz'utujil village.

It should be noted that the image venerated in different latitudes of Central America, Mexico and the United States corresponds to that of San Andrés Itzapa, Chimaltenango, and the family and botanical units are in charge of guarding and protecting his cult through the Sacred Tables, in which the witchdoctors "administrators of the gift" are responsible for keeping the saint clean, organizing the feast on October 28 and performing works of white or black witchcraft for the devotees who come with him. Undoubtedly, this form of organization is complex because it incorporates Saint Simon as a member of their family unit.

The mobility of the saint has been captured by Antonio García-Espada in his text "Los cumpleaños de san Simón. Etnografías salvadoreñas" (2016), which records two feasts in El Salvador and distinguishes, through cultic practices, different symbolic contents: for example, in the feast celebrated in Tamanique the saint is not offered alcoholic beverages, that is, he is abstemious, since the dominant religious context punishes alcohol consumption (García-Espada, 2016: 165); while in Cuyultitlán, where he is also venerated, the feast summons diverse social sectors, the attendees get drunk and offer various liquors and beers to the saint (García-Espada, 2016: 172).

The styles of the religious practices of the cult of Saint Simon are varied in their transit through different spaces. In my work "Prostitution and religion: the Kumbala Bar and the cult of Saint Simon in a place called Macondo on the Mexico-Guatemala border" (Marín-Valadez, 2014) I presented an investigation in the prostitution zone of a municipality bordering Guatemala, where the saint acquires an important meaning for the local sex workers, since their condition as women, migrants, prostitutes and mothers accentuates their vulnerability. During my approach, I ethnographically recorded ritual activities, such as offerings, feasts and punishments, practices that contain a deep meaning in the lives of these women who, being excluded from Judeo-Christian churches because of their condition as prostitutes, find in Saint Simon a spiritual refuge that symbolically mitigates their vulnerability (Marín-Valadez, 2014).

The traces of the saint are also recognized by Sylvie Pédron-Colombani, who has investigated the cult in Guatemala and the United States, which has contributed significantly to the knowledge of this devotion. The author points out in her text "The cult of Maximón in Guatemala" the recoding of the image of Maximón outside of Santiago Atitlán and the place that this devotion has in the complex religious field (2008); furthermore, in "The patrimonialization of Saint Simon in Los Angeles" (2017) she describes the way in which the migratory movements of Guatemalans to the United States intensified after the weakening of the welfare state, a situation that allowed their relocation to Los Angeles. Pédron-Colombani (2017) focuses on recognizing the patrimonialization of Saint Simon by Guatemalan migrants vis-à-vis the Black Christ of Esquipulas, which is another transplanted devotion articulated to Guatemalan identity. In his text he presents some situations in which the saint is intertwined with the condition of Guatemalan migrants, one of them, as a protector saint, and another, as the border patrol.

Based on the reflections in the collective book by Carolina Rivera Farfán, María del Carmen García Aguilar, Miguel Lisbona Guillen, Irene Sánchez Franco and Salvador Meza, Diversidad religiosa y conflicto religioso en Chiapas. Intereses, utopías y realidades (2005), I take up one of the main ideas that allow us to understand the crossroads between religion and human mobility as follows: "people, when they migrate, take their religions with them" (2007: 259). This simple phrase raises the complex scenario in which different belief systems have been disseminated through migratory mobility and unsuspected latitudes, in the usual sacred territories and in which Saint Simon has crossed borders, flourishing and strengthening itself in new spaces, where, in addition, it plays a contradictory role resulting from the ambivalence that allows condensing the symbolic expressions of its devotees or believers.12

St. Simon, an itinerant religiosity

O mighty Saint Simon, I, a humble creature rejected by all, come to prostrate myself before you to ask your protection from every danger. If it is in love, you will stop the woman I love; if it is in business, may she never fall; you will not let the sorcerers have more power than you; if it is my enemy, it is you who will win; if they are hidden enemies, you make them leave as soon as I name you. O mighty Saint Simon, I offer you your cigar, your tortillas, your candle. Great art thou, Lord, drive away the people I owe money or death, I ask thee for him whom thou didst deliver for thirty coins. Oh, Judas St. Simon.

In most of the bars and cantinas in the municipalities that are part of the Soconusco-Istmo Costa migratory circuit, there are small and luminous altars with different virgins and saints, such as the Virgin of Guadalupe, Saint Jude Thaddeus, Saint Death, Buddha, Jesus Malverde, among others; however, the figure that is constantly present and occupies the central place in the altars is Saint Simon. The owners of these businesses are the ones who have placed the figure, since, within the narratives, Saint Simon is attributed to the success of the businesses in this line of business because he likes intoxicating beverages. Likewise, small ritual organizations have been created in the bars, made up of sex workers and/or ficheras.13 who are devotees of the saint, most of them of Central American origin, who distribute various activities: arranging the altar and reciting the prayer to the saint; removing the extinguished candles and the withered flowers, as well as cleaning the plastic flowers; changing the beer containers and, before placing the new ones, spilling some of the drink on the floor; throwing away the "bachichas" from the cigarettes and, when the saint is placed on the altar, they put one on the pinzón on his face while the ashes are read, since they assure that if the ashes remain intact in the cigarette, Saint Simon is happy. In these spaces there is no rigid dynamic regarding the ritual, since it can be performed at any time of the day while attending to the customers who arrive early in the morning.

One of the most important practices in the bars is the feast of St. Simon, celebrated on October 28, which begins at dawn, when one of the bar's devotees starts to thunder "rockets", which is the signal for the other devotees to arrive at the establishment and sing to her. Las mañanitas, the Cumbia de Monchito and dance with him to popular music. Throughout the dawn and morning, the celebration is intimate. At 11:00 a.m., when the doors of the bars open, some customers "invite" the saint for a few beers. On certain occasions, women buy chicken broth or Chinese food, since these are the favorite dishes of Saint Simon. In some bars, after or before the feast, some sex workers and/or ficheras have organized trips to the interior of Guatemala to visit his temple, either in Zunil, Quetzaltenango or in San Andrés Itzapa, Chimaltenango.

The religious field in the towns that are part of this migratory circuit is very diverse, although Christian churches and congregations predominate; consequently, devotion to Saint Simon is carried out in intimate spaces because it is qualified by the majority as "idolatry to Satan." In addition, women who work in these establishments, especially if they are Honduran, carry various social stigmas and are referred to as "las mujeres de cantina." It is therefore important to recognize how populations living in marginalized and vulnerable situations build their own communities and organizations.

These women have been marked by being sex workers and/or ficheras, as well as by their national origin; they are exposed to various situations of social exclusion, discrimination and violence. In this sense, Saint Simon is a devotion that produces community, since, despite the competition among them (for clients, money, etc.), they manage to unite through their devotion to the saint and consolidate support networks articulated by solidarity, inclusion and a sense of belonging.

Devotions in mobility

Migration in transit through the Soconusco region in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, is a phenomenon that cannot be reduced solely to migratory caravans. Although these large mobilizations capture media and social attention due to their magnitude and organization, a significant part of the migratory flows occur in small groups or even individually. In this modality, the conditions of vulnerability may increase because, given the lack of presence of the media and human rights observers, migrants traveling in small groups are more exposed to human rights violations.

Thus, small groups of migrants in transit park in different municipalities to rest, receive money at convenience stores or look for better ways to continue their journey to their first destination, which is the municipality of Arriaga, where the migratory transit forks to San Pedro Tapanatepec, Oaxaca, or to Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, where they request temporary permits to cross the national territory and enter the United States.

The migratory transit population has become more diversified14 The number of new agents, mainly from Venezuela, Colombia, Haiti, Cuba, Ecuador, Peru and the Dominican Republic, as well as people from countries in Asia and Africa, has increased in the last decade, and some of them, who do not speak Spanish, use their cell phones to communicate with the local population, thanks to the fact that many applications allow translation. ipso facto.

At the transportation terminals that connect several municipalities in the Soconusco and Istmo-Costa regions, migrants tend to gather in order to get a means of transportation to their destination; sometimes, the crowds make them wait for several hours and, in the meantime, they look for food and electrical connections to charge their cell phones. Local people who have food businesses nearby have implemented strategies to attract migrants; for example, they hang flags in their establishments, mainly from Venezuela, Honduras, Colombia and Cuba, since they have identified that most of the people in transit come from these countries; they have incorporated some typical dishes such as arepas, Colombian empanadas and tajadas, and they even buy flour of the brand name bread by Mercado Libre to offer its customers a culinary experience closer to their cultural experiences.

In this scenario, the manifestation of the sacred occurs constantly. In more than a year that I have been making this record, I have observed the diversity of religious expressions that pass through the circuit. Although it has been impossible in many cases to obtain an interview, I have noticed the multiplicity of devotions that pass through this corridor. A clear example happened in November 2023, when I had the opportunity to meet five young people from Bangladesh, who were wearing hats called tupis and, with certain difficulties generated by the language, they told me that they had arrived through Puerto Madero and that they were Muslims; they had not found transportation and spent the night in the park of the municipality of Escuintla.

In this diversity of religious expressions, the body plays a fundamental role in the manifestation of the sacred, since young people of different origins and religious affiliations have tattoos that tell stories related to their mobility process, as in the case of Isaac, a 35-year-old Cuban, who had tattooed the image of his daughter, who lives in North Carolina, the place where he was looking to go, since most of his family was there. He got the tattoo when his partner decided to emigrate to the United States. Another tattoo he had was that of Eleguá, a deity of Cuban Santeria, which he got when he began to organize his departure in Cuba, since he is the saint of the roads and assures him to reach his destination. Isaac traveled accompanied by different people he met in Guatemala who also practiced Santeria.

Religious practices in the migratory circuit of the Soconusco Istmo-Costa are profoundly diverse and are expressed in multiple ways. In relation to narrative, I take up the reflection of Jorge Yllescas Illescas in his article "Los altares del cuerpo como resistencia ante el poder carcelario" (2018), in which he exposes the symbolic content in religious tattoos. Now, the author focuses his study on prison spaces and his discussion allows us to recognize the multiple spaces in which hierophany occurs.

Tattoos become a means of linking the wearer to his or her numen. Through them, the inmates can protect themselves from an evil or invoke it, they embody the pacts with their beliefs and give them identity. But this identity is not precisely one that alludes to belonging to a group, but one that is born from a personal decision, so that the choice of the drawing responds primarily to a personal initiative and an aesthetic preference, it is not a gesture of adhesion (Yllescas, 2018).

Continuing with this discussion, in the context of migratory mobility, tattoos play two main roles: one of them, as the author points out, is to articulate the believer with his devotion in order to symbolically resolve the challenges he encounters along the way and produce certainties of reaching the objectives of his odyssey; Another is that through the tattoos, similar communities are recognized in relation to belief systems, since, in Isaac's case, he did not leave Cuba with the other migrants, but they met during the journey and identified themselves through the tattoos; in this sense, the sense of belonging acquires a significant importance and manages to mitigate the uncertainty caused by the migratory dynamics in transit.

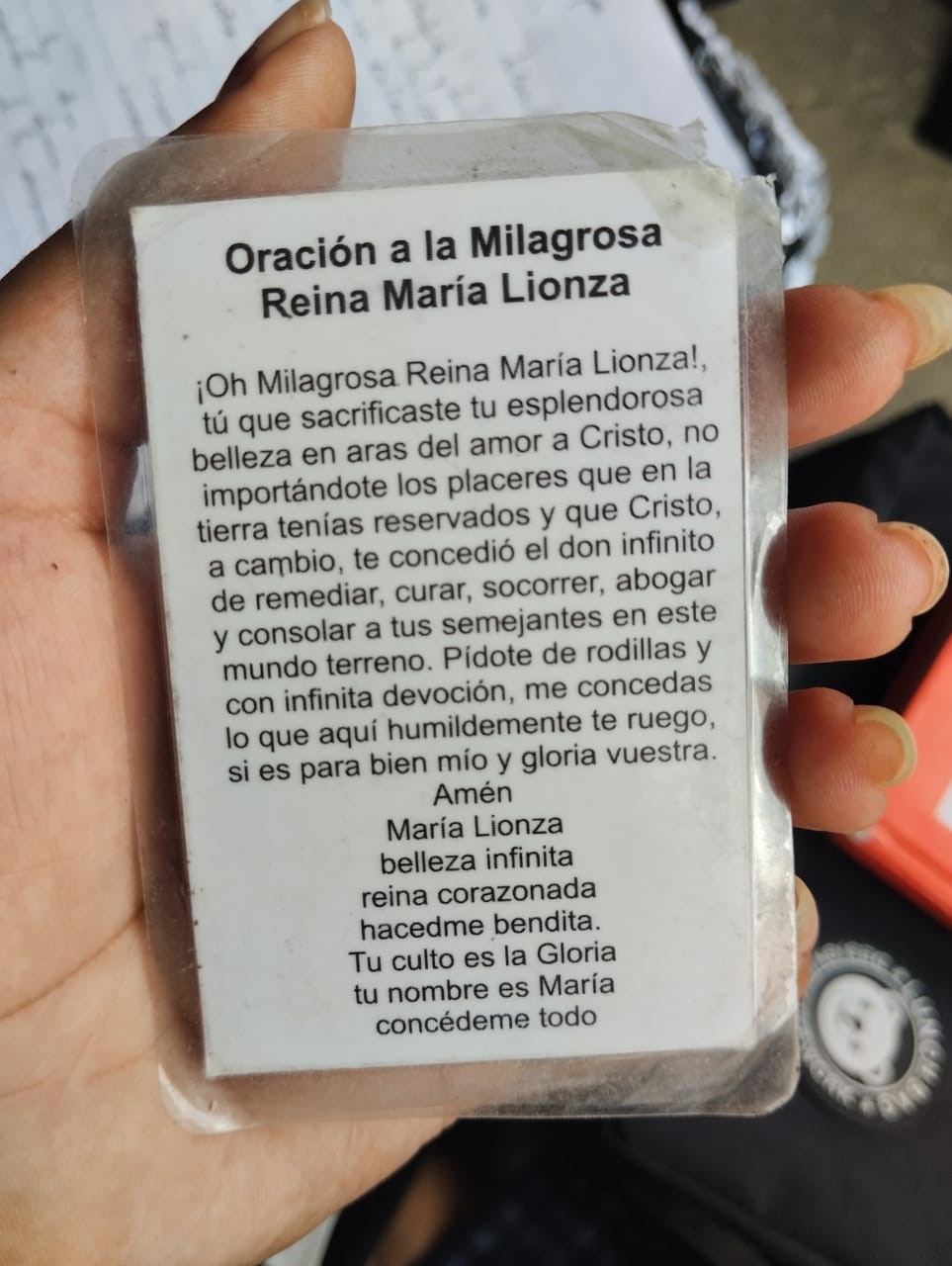

In the same space of the transport terminal I met Marcelo, Janis and Julieta, of Venezuelan origin, members of the community lgbttiq+, who were sitting on the asphalt at the side of the road waiting in line to get on one of the public transports. Marcelo caught my attention because of the extravagance of his outfit., as he was wearing a golden suit that clung to his slim body, and he was also wearing dreadlocks and several tattoos of Maria Lionza.15 in her arms. Those religious images prompted me to approach her and ask her if the tattoo she was wearing was about that deity; with a little mistrust, she answered me in a straightforward manner that it was so and that she was the queen of the Sorte mountain. Janis and Julieta approached me surprised by my curiosity and asked me if I knew the "queen"; I explained that I had read some things about her and that the image seemed very beautiful to me; they also told me that they were devotees and that Marcelo was, in addition, a spiritualist.16

Marcelo grew up in a Catholic family that has always venerated María Lionza; since he was a child he used to go with his mother and grandmother to the town of Yaracuy for the celebration at the Sorte Mountain on October 12, offered to María Lionza and her heavenly court, who cure people of their ills by possessing their bodies. Marcelo, along with her friends, attended the Sorte Mountain in 2021, before starting their journey to the United States, with the purpose of asking for protection during their trip; they lit some cigars in front of an altar of Maria Lionza and were predicted success, but endless adversities. Then they approached one of the courts where some drums were playing; at that moment Marcelo fainted and then joined the dance to the rhythm of the music and lost his mind, but Janis and Julieta testified that, while dancing, her breasts began to grow, which meant that Maria Lionza had possessed her body. The dance lasted about an hour, until she again fell to the floor, and the ritual attendants sprinkled alcohol on her face. The trance had been very heavy for Marcelo's weak body, who later woke up in pain. When the witnesses of the trance told Marcelo what had happened, he was very astonished and joyful, for he felt that it was a manifestation of the protection of the mountain saint.

In the narrative presented, Marcelo's encounter with María Lionza is presented, which strengthened his decision to migrate to the United States and to face the possible uncertainty about his purpose; it is this narrative that has allowed him to revitalize his decision and continue the journey, despite the challenges he faces along the way. In the context of mobility in transit, the narrative has become a social fabric in which the belief systems that give meaning to the odyssey are articulated and endorsed. "María Lionza manifested herself in Marcelo's body, while he was in a trance, according to him and his friends," and that manifestation gave the young man the security to reach his goal. Subjects who find themselves in the multiple dynamics of mobility need to reaffirm the meaning of their experience. In this sense, Manfredi Bortoluzzi and Witold Jacorzinsky, in their introduction to the book Man is the flow of a story: anthropology of narratives. (2017), point out that individuals are essentially "narrative" and life is organized and understood from the stories we tell about ourselves, about our experiences, about the world we inhabit; to show this, the authors turn to Rabindranath Tagore's poem "Liptika" which points out the following:

The creator made Man develop in one tale after another. The life of animals and birds is reduced to eating, sleeping and caring for their young; but the life of man consists of storytelling, because of all that he has to endure and experience, his sorrows and joys, the good and bad acts he performs and the reactions they provoke, as well as the mill that generates the clash of one will against another, of one against ten, of desire against reality, of nature against inspiration. Just as a river is a stream of water, man is the flow of a story (Tagore, 2001: 36, in Bortoluzzi and Jacorzynski, 2010: 9).

Soconusco is a scenario where the crossroads between the multiple dynamics of mobility and the religious and cultural references of migrant populations is fully exposed. In this sense, exploring the importance of religion in migratory mobility allows us to understand that religious beliefs and practices not only accompany the subjects in their journey, but also help the subject in mobility to express himself in a symbolic way to face the challenges of the contexts to which he is integrated, that is, they are a significant instrument in decision making, In other words, they are a significant instrument in decision-making, in the formation of communities, in solidarity networks and in the sense of belonging in the face of the uncertainties of displacement, the region "must" be recognized as a dynamic migratory circuit through which diverse beliefs, cultures, histories and ways of life circulate, disrupting the migrant subjects and the receiving populations.

As this paper has shown, María Lionza, Eleguá, Saint Simon and the prayer recited by John, in which migrants are socially represented as God's chosen people, are devotions that are mobile. In this sense, the reflections of Renée de la Torre and Patricia Arias in the book Religiosidades trasplantadas. Religious recompositions in new transnational scenarios (2017) make it possible to recognize the way in which religious practices adapt and resignify themselves in contexts of mobility, since migrants, by transplanting their religious traditions and symbols to new cartographies, not only recompose their identity, but also reconfigure their new "places", where the religious allows them to reconnect their past and present.

Along the same lines, religious practices cannot be understood as reproductions, but rather as creative processes that reflect the capacity for agency of mobile subjects, which help them to re-signify their environment and the experiences of their journeys.

Bibliography

Bortoluzzi, Manfredi y Witold Jacorzynski (2010). “Introducción”, en Manfredi Bortoluzzi y Witold Jacorzynski. El hombre es el fluir de un cuento: antropología de las narrativas. Ciudad de México: Publicaciones de la Casa Chata, pp. 9-22.

De la Torre, Renée y Patricia Arias (2017). “Introducción”, en Renée de la Torre y Patricia Arias (eds.). Religiosidades trasplantadas. Recomposiciones religiosas en nuevos escenarios transnacionales. Ciudad de México: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte/Juan Pablo Editores, pp. 13-35.

Debroy Arriaza, Iracema Maribel (2003). “Magia, religión y ritos. Un acercamiento etnográfico a la cofradía de San Simón del municipio de San Andrés Itzapa, departamento de Chimaltenango”. Tesis para obtener el grado de licenciada en Antropología. Ciudad de Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos.

Fenner, Justus (2019). Neutralidad impuesta. El Soconusco, Chiapas, en búsqueda de su identidad, 1824-1842. Ciudad de México: cimsur-unam.

Fuentes Malo, Sinue Hammed y Enrique Coraza de los Santos (2023). “El pueblo mam de Soconusco. Recuperación de su memoria y su realidad ante el proceso de mexicanización”, Región y Sociedad, 35. https://doi.org/10.22198/rys2023/35/1760

García-Espada, Antonio. (2016). “Los cumpleaños de San Simón. Etnografías salvadoreñas”, Liminar, 14(2), pp. 163-181.

Marín-Valadez, Blanca Mónica (2014). “Prostitución y religión: el Kumbala Bar y el culto a san Simón en un lugar llamado Macondo de la frontera México-Guatemala”. Tesis para obtener el grado de maestra en Antropología Social. San Cristóbal de las Casas: ciesas-Sureste.

Mendelson, E. Michael (1965). Los escándalos de Maximón. Guatemala: Instituto Indigenista de Guatemala.

Pédron-Colombani, Sylvie (13 de octubre de 2008). Trace. Recuperado de El culto de Maximón en Guatemala: http://trace.revues.org/457

— (2017). Patrimonialización de san Simón en Los Ángeles, en Renée de la Torre y Patricia Arias (eds.). Religiosidades trasplantadas, recomposiciones religiosas en nuevos escenarios transnacionales. Ciudad de México: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte/ Juan Pablos Editor, pp. 213-244.

Pollak-Eltz, Angelina (2004). María Lionza. Mito y culto venezolano, ayer y hoy. Caracas: Universidad Católica Andrés Bello.

Rivas Castillo, Jaime (2011). “¿Víctimas nada más?: migrantes centroamericanos en el Soconusco”, Nueva Antropología, 24(74), pp. 9-38.

Rivera Farfán, Carolina (2014). “Introducción”, en Carolina Rivera (coord.). Trabajo y vida cotidiana de centroamericanos en la frontera suroccidental de México. Ciudad de México: Publicaciones de la Casa Chata.

—, María del Carmen García Aguilar, Miguel Lisbona Guillen, Irene Sánchez Franco y Salvador Meza (2005). Diversidad religiosa y conflicto religioso en Chiapas. Intereses, utopías y realidades. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social/Consejo de Ciencia y Tecnología del Estado de Chiapas/Secretaría de Gobierno del Estado de Chiapas/Secretaría de Gobernación.

Tagore, Rabindranath (2001). “Liptika”, en Obras selectas. Madrid: Edimat Libros.

Tovar, María Elena (2000). “Extranjeros en el Soconusco”, Revista de Humanidades: Tecnológico de Monterrey, 8, pp. 29-43.

Valenzuela, Erika y Olga Odgers (2014). “Usos sociales de la religión como recurso ante la violencia: católicos, evangélicos y testigos de Jehová en Tijuana, México”, Culturales, 2(2), pp. 9-40.

Vallejo, Alberto (2005). Por los caminos de los antiguos nawales: Rilaj Maam y el nawalismo maya tz´utujil en Santiago Atitlán. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Yllescas Illescas, Jorge Adrián (2018). “Los altares del cuerpo como resistencia ante el poder carcelario”, Encartes, vol. 1, núm. 1, pp. 121-131. https://doi.org/10.29340/en.v1n1.20

Blanca Mónica Marín Valadez holds a degree in Social Anthropology from the School of Anthropology of the University of California, Berkeley. uvM.A. in Anthropology at ciesas-D. candidate in Mesoamerican Studies at the Universidad de la Plata. unam. He received an honorable mention from the inah in 2015, in the Fray Bernardino de Sahagún category with the master's thesis "Prostitution and religion: the Kumbala bar and the cult of Saint Simon in a place called Macondo on the Mexico-Guatemala border". She has participated in publications in Mexico, Poland and Guatemala, and has taken part in several colloquiums and congresses. His main lines of research are popular religiosities, violence, migration and border between Mexico and Guatemala. She is a member of the Mexican Society for the Study of Religions (smer) as of March 3, 2020.