Ejido El Porvenir in Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California. Experiences and memories of an agricultural community

- Rogelio E. Ruiz Rios

- ― see biodata

Ejido El Porvenir in Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California. Experiences and memories of an agricultural community1

Receipt: October 3, 2023

Acceptance: April 2, 2024

is a researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas of the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. D. in History from El Colegio de Michoacán. Member of the National System of Researchers (sni) of the conahcyt level i.

Research topics: recent historiographical trends, tensions between history and memory, history and post-humanisms, colonization and occupation in Baja California, communities, utopias and futures. Research networks: Present Time History Network, Research Network on Communities, Futures and Utopias of the Latin American Anthropology Association, member of the Communities and Futures Project of the Frontier Science call of the Latin American Anthropology Association. conahcyt for the period 2023-2025.Abstract

This article addresses the creation and consolidation of the ejido El Porvenir, an agricultural community located in the Guadalupe Valley, Baja California, as one of the agrarian distribution projects undertaken by the Mexican State. To this end, we describe and analyze the substantive facts in the temporary development of the ejido and its community expectations in a border context subject to the corporatist practices of the Mexican State and the pressures of the regional market, private initiative, competition with neighboring communities and climatic phenomena. The research is based on governmental and private archives, bibliographic and hemerographic consultations, memories and testimonies in physical and digital formats.

Keywords: agrarianism, community, ejido, nationalism, Guadalupe Valley

Ejido El Porvenir in Valle De Guadalupe, Baja California: Experiences and Memories of a Farming Community

The founding and development of Ejido El Porvenir in Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California, is the topic of this article. This farming community is one of the Mexican government's land redistribution projects. In the analysis, historic events of the community are analyzed along with the community's expectations in this border region, the corporatism of the Mexican government, the pressures of the regional market, private enterprise, competition with neighboring communities, and weather events. The research draws on government and private archives, literature and newspapers, and memories and testimonies both physical and digital.

Keywords: ejido, land reform, nationalism, Valle de Guadalupe, community.

Methodological guide

Community identities are forged in historicity relations related to multitemporal scales and rhythms that frame events, memories and personal and collective experiences that occurred simultaneously and diachronically.2 In this article I address from these perspectives the processes of configuration of the ejido El Porvenir (ep hereinafter) started in late 1937 in the Guadalupe Valley (hereinafter vdg), Baja California. The set of memories and historical records used in this research can be classified into three areas. The first comprises testimonial material and evidence produced by the bureaucratic procedures involved in the creation and territorial expansion of the ejido. epThe documentation begins in 1937 with the process of founding an ejido and continues until 1959, when the land was expanded. The documentation begins in 1937 with the procedures for founding an ejido and continues until 1959, when this agrarian nucleus was expanded. Antoinette Burton considers that documentation of this nature constitutes "memories of the State" as sources, repositories and established historical actors. Thus, Burton warns, one must take into account how archives are constructed, policed, experienced and manipulated, recognizing that even the most sophisticated archival work does not overcome the claims of objectivity for which archives have been synonymous (Burton, 2005: 7). In a similar vein, Matt Matsuda notes that, through methodological treatment, historiographical research homogenizes, to some extent, archives of diverse origin. For Matsuda, memory is an appropriated and politicized object that can be nationalized, aestheticized and profiled in terms of gender, as well as commodified, so that the state remembers and acts through the documents and practices and institutions that constitute its own memory (quoted in Robinson, 2005: 81).

It is commonly assumed that the optimal use of a methodology and research expertise are sufficient to mitigate the disparities that exist between the various types of memories and records consulted. It should be clear that research materials have particular origins and purposes, and that they carry intrinsic power relations capable of silencing and inhibiting certain types of experiences, while enhancing and highlighting others. Enzo Traverso distinguishes between "strong" and "weak" memories in opposition in cases such as those of "official memories, maintained by institutions, even by States, and [the] subway, hidden or forbidden memories". Thus, whether a memory is visible and recognized will depend on the strength of its bearers (Traverso, 2007: 86). This is complemented by Michel-Rolph Trouillot's statement that the material treasured as historical evidence is imbricated with the distances between power and silence; thus, the challenge lies in discerning "the multiple ways in which the production of historical narratives involves the irregular contribution of competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to the means to produce History" (2017: xxviii). If in historical research there is an eagerness to present a reflective, analytical balance, with aspirations of objectivity based on the articulation and synchronization of diverse experiences in time and space, the existing disparities and hiatuses must be identified in the processes of consultation and processing of research material, as well as in the analysis, reflection and reportage.

A second order of the documentation and records reviewed here comes from the testimonies and experiences gathered between 1997 and 1998 by a research group in which I participated, with the purpose of creating an "archive of the word" at the Autonomous University of Baja California (hereinafter referred to as "the archive of the word"). uabc) to serve as the basis for a series of historical accounts projecting the point of view of the people of the region. vdg. The storage, transcription, cataloguing and consultation procedures to which this material was subjected, whose content sometimes disagrees with the official and officialist memories -although in others it coincides-, give it an ambivalent condition. On the one hand, it is a memory of community or individualized roots, which, given the origin and process to which it has been exposed, is institutionalized. However, it is also one of the few resources that allow access to the testimonies of those who participated directly in the settlement and development of the area. vdg (who are mostly deceased).

A third order of documentation that nourishes this work are records and data of different formats, such as images and comments shared by residents of the following communities, of their own free will and without institutional mediation ep and their descendants on social networks, mainly on the Facebook page "Porvenir memoria fotográfica".3 In recent years, a sector of the ep has expressed on digital platforms its desire to recover and share photographs, documents and personal and collective testimonies. These memory exercises are often encouraged by feelings of nostalgia and melancholy among older adults to prevent forgetfulness and to extend their bonds of coexistence and familiarity in their kinship networks. My access to these records has been like that of any user as they are available on social networks without any restriction as memories, memorable objects and with testimonial value to attest to some fact or event. They have, therefore, a emic which does not necessarily diverge them from the narrative lines followed in the "state memoirs". In addition to the above, I have consulted bibliographic and newspaper material and academic works that have also served as inspiration, record and reservoir of information to reinforce or propose the narrative lines imbricated in the collective memories referred to in this work.

The origins of the ejido

In the process of institutionalization of the Mexican Revolution that began in 1910, agrarian reform was one of the axes of social justice expressed in Article 27 of the Political Constitution promulgated in 1917, which established that the land and surface and subsoil resources were the property of the nation and that the State had the power to grant them in concession. Popular pressures in favor of agrarian distribution led to the presidential decree of August 2, 1923, which provided for the granting of farmland to Mexican citizens (thus, in masculine) who lacked plots of land through the distribution of uncultivated, national and idle land; for this it was required to have Mexican citizenship, to be at least 18 years old and to be without other possibilities of acquiring land. The entry into force of the decree detonated the notices of occupation of national lands. It was enough to occupy the land claimed and request it in writing to the agrarian authorities and the property registry. Private, ejido and previously occupied lands were exempted from the affectation. In the opinion of Moisés T. de la Peña, the government suspended the decree in 1926 due to the difficulties involved in "legalizing the numerous occupations", and only reactivated it until 1934 with modifications that made the procedures more bureaucratic (1950: 190).

Agrarian distribution was intensified during the presidency of General Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940). The agrarian and demographic policies were linked in the first General Population Law decreed in 1936, which sought to increase the country's population, balance its distribution throughout the national territory and promote miscegenation. With these objectives in mind, the repatriation of Mexican immigrant families or those born in the United States of America was promoted (henceforth usa). Population growth was encouraged through natural growth, repatriation and immigration. Article 29 stipulated that it was the power of the Ministry of the Interior to "distribute and accommodate repatriates and immigrants, founding, as the case may be, agricultural or industrial colonies", in addition to facilitating their transfer to Mexican soil when there was justification (Diario Oficial, 1936: 3). Those who returned to the country after having resided abroad for at least one year were considered "repatriated" (Diario Oficial, 1936: 5). It was established in the law to encourage migratory currents "towards the most convenient places" in the country, that is, those with lower demographic density, those that required economic development and the strengthening of the "national culture". Article 6 of the 1936 Population Law sought the "Mexicanization" of the border in order to stop the risk of invasions from the following areas usa and counteract the cultural influence of the neighboring country on local populations. The low demographic density, compared to other entities in the country, and the border location with usaThe Mexican authorities determined that Baja California would be a priority destination for repatriation.

The objective was for the returnees to have the "most complete reintegration into the country"; therefore, it was up to the Mexican foreign service to follow up on "the Mexican emigrants" in order to take advantage of their knowledge and skills obtained abroad. In addition, it was stipulated that the "repatriated farmers" should acquire machinery and tools to facilitate their settlement and productive activities in the regions of the country considered relevant by the authorities, providing them with social, political and legal protection, tax and administrative incentives (Diario Oficial, 1936: 4).

The repatriation plans were echoed among a certain sector of the Mexican-origin population in usa. The racism experienced in that country, aggravated by the economic crisis of 1929 (cf. Wallis, 2010: 141-146) motivated his desire to repatriate. Candelario Carreón's life experience [pho–and/1/37(1)] describes the vicissitudes of the repatriation process. Carreon was born in 1920 in the state of Kansas, usaShe grew up between that country and the state of Guanajuato where her family came from. Candelario's consort was also a native of usa and raised in Mexico. Carreon said they decided to return to Mexican territory after hearing on the radio that land and equipment were being given to those who wanted to return. Candelario's father gathered the family for this purpose. Previously, Pedro, one of his brothers, had visited Baja California as part of a delegation interested in repatriating, so they visited several ejidos in order to evaluate the availability and condition of the land. In the town of Gardena, near Los Angeles, interested persons had formed committees to raise funds. From there they sent outposts to inspect the land and ejidos in Baja California, including Candelario's brother Pedro. The Carreon family crossed into Mexico on August 18, 1939, with the exception of one of his brothers who decided to remain in Mexico. usa. The family was concentrated in Los Angeles, California, where the Mexican government provided transportation to Mexico and, according to Candelario, California state authorities also collaborated with resources and facilities for their return.

The data provided by another interviewee, Alfonso García [pho-e/ 1/30(1)], allow us to broaden the perspective on the composition of the repatriated families. Alfonso was born to a father from Guanajuato and a mother from Durango. USA, where she had nine sons and daughters; in 1939, they repatriated to settle in ep where they had three more sons and daughters, including Alfonso, born on the ejido in 1941.

El Ejido ep was founded on the west bank of the vdgapproximately 28 kilometers northeast of the port of Ensenada. In the memories of Candelario, who found the way of speaking of the other founders of the ejido "very curious", the impression of those who took part in these events, seeing themselves congregated in a place that seemed strange to them together with other unknown people from various Mexican states and from other countries, is evident. usa. In the days following his arrival, the sense of otherness increased as he came into contact with the Russian Colony [hereinafter cr(also called Colonia Guadalupe), five km east of the ejido.4

The historical discrimination suffered in usa by people of Mexican origin served as a parameter for the repatriated families in their relations with the population of Russian origin. Looking back on those years, in addition to the racial experience in usaThe marks of difference instilled between the Mexican population, self-perceived as "mestizo", in relation to the native peoples, which in this case was the Kumiai community of San José de la Zorra, stand out.5 [hereinafter sjz]:

at that time there were many girls [in the ejido] and they didn't want them to cross paths with the Russians, because they had the impression that Mexicans were like those from San José de la Zorra, that they were indigenous [...] and they were therefore from Russia, in a certain way superior, according to them, and that's why they told us '...they were not the same as the Russians [...].chorny mexicansky'6 which means black or black.

Carreón considered the founding of the ejido as an imposition of the will of the founding families on nature, a demonstration of ingenuity in having to improvise in the face of scarce conditions. He said that on the land where they camped there were coyotes, snakes, "Russian cows", as well as "pure chamizo", because "it was a primitive shot". They got their water from a waterwheel. He remembered that period with pride and satisfaction because it gave way to everything that is in the present. Cultural exchanges stand out in these foundational experiences. Carreón pointed out that upon arrival they settled in a tent made by the army of usabut later his father made "a little house in the Mexicali style, of cachanilla and reed", a construction model they took from the people from the Mexicali Valley, since "many who came here came from there, like the Cerda family", although later "they made the houses with adobe bricks like in Mexicali [...] they were a little more modern, we were made of cachanilla". However, the heavy rains of September 19, 1939 forced them to replace the tents with cachanilla houses. The storm caused flooding and the breakage of the tents where they were sheltered. According to Carreón, as a result of the damages caused by the water, "the Russians" helped them with wheat flour processed in their own mill, in spite of the fact that "they believed that we came in the spirit of war, no, we came in the spirit of peace, we came to make homeland, later they realized it and said 'chócala', and we got along well". The expression "to make homeland" reflects a certain degree of awareness and conviction among the people of the ejido of what their presence meant in the vdg. In effect, nationalism and patriotism were feelings exalted by the revolutionary regime that sought to mold a certain type of citizenship identified with mestizaje, through the various institutions and material and symbolic resources mobilized and deployed by the State. Civic rituals, educational programs, artistic manifestations and a diversity of ideological devices permeated public and private spaces, strategies to recreate and reinforce those feelings were installed in everyday dynamics, a process that may well fit into what Michael Billig (1998) conceptualized as "banal nationalism" as a mechanism to reproduce national identity on a daily basis.

The experience narrated by Mariana Ramírez [pho-e/1/24/(1) and (2)] provides additional information about the founding of the ejido. She lived with her family in Buena Park, California. Her husband was working in the fields when he began to attend meetings where they were told that President Lázaro Cárdenas was giving away land for those who wanted to return to Mexico. Thus, several families returned to Mexico in August 1939 via Mexicali, one of the points established by Mexican authorities for repatriation, aboard automobiles (unlike the Carreón family who traveled by bus); they brought their belongings and animals with them. Families from different parts of Baja California and Mexico also participated in the founding of the ejido. The testimony of Silvia Lugarda, daughter of the ejido's founders and a resident of the ejido, helps in this regard, as well as emphasizing the distinctions between ejidatarias and people of Russian and Kumiai origin:

We arrived at the Guadalupe Valley, on February 22, 1938, here it was pure water and there was nothing but bronco horses [...]; the horses of the Russians and the Indians and God knows who else! Because this was abandoned, it was alone, it was pure bush. The crops were there, but over there on the Russian side, over there in the valley of the Russians [...] at that time it was far away (in Ensenada, 1999: 679-680).

Until 1938, the cr was the main population center in the vdg. The settlement was founded in 1905 under the colonization, naturalization and foreigner laws in force during the Porfiriato period. In turn, recognition as a native population in the vdg corresponds to the Kumiai population congregated in two settlements: sjz and San Antonio Necua [hereinafter saint]. The latter community is located southeast of the valley, a little more than 10 km from the ejido. In addition to the aforementioned communities, Mexican and U.S. citizens lived on nearby ranches.

The application to form the ejido began on September 19, 1937 in the name of the agrarian group "El Porvenir" in compliance with the Agrarian Code. One requirement was the prior existence of a settlement in the place where the ejidal nucleus was to be created, with a minimum of 20 individuals with land rights. The individuals with land rights had to lack sufficient land to support their families and had to have resided for at least six months in the locality where the ejido was to be founded. The most important town in the area where the ejido would be located would be taken as the base for the settlement, and a radius of seven kilometers around it would be drawn, within which national and privately-owned lands larger than a certain extension could be affected.7

Candelario Carreón recalled that one of his older brothers told him that, during the early days of organization, the group of agraristas used to refer to the future ejido by the name "Guadalupe", but in one meeting, Manuel Hernández, a long-time resident of the vdgproposed calling it "El Porvenir" to avoid confusion with the "Colonia Guadalupe", and argued that the ejido had "a lot of future" [...].pho-e/1/37(1)]. The families requesting the creation of the ejido had the support and advice of agrarian leaders and activists from other parts of the Ensenada area. On September 29, 1937, the governor, in accordance with the Agrarian Code, designated the representatives of the petitioning group as members of the Agrarian Executive Committee and informed the Mixed Agrarian Commission based in Mexicali (the political capital of the entity). The request for the creation of the ejido was published in the Official Gazette The Northern Territory on October 10, 1937, with which the respective dossier was created. Afterwards, an official commission visited the vdg to make the first demarcations and delimit the legal estate.

The governor of the then Northern Territory of Baja California, Lieutenant Colonel Rodolfo Sánchez Taboada, received the request for an ejido endowment at the cost of the "idle lands" of the vdg belonging to the San Marcos or Huecos and Baldíos ranches, Bella Vista or Rancho Barré, and the cr. The petition alleged that the petitioners lacked land "despite being natives, Indians and Mexican citizens", while the lands claimed were almost entirely "unduly and illegally in the hands of foreigners". By "foreigners" were meant the Russian families and the estate of Dolores Moreno de Cheatam,8 owner of the Bella Vista ranch, whose heirs, surnamed Flower Moreno, were born in Mexico, but had U.S. citizenship; Percy Barré, the widower of one of the heirs, was also a U.S. citizen and in charge of the ranch.

The "Mexican" population in the vdgThe Mexican families, less numerous than those of Russian origin, lived dispersed in the ranches of the area, dedicated to agricultural and livestock work. At the end of 1937, the government had already sent an engineer to inspect the lands susceptible of being affected; he reported that only three Mexican families lived in the area. vdg. From various records we can establish that these were the families of the school teacher in the school in which the teacher's family was enrolled. crThe distinction between the Russian and Mexican populations is due to ethnic criteria rather than citizenship. The distinction between the Russian and Mexican populations is due to ethnic criteria rather than citizenship, because, although the majority of those who made up the cr had spent almost their entire lives in Mexican territory, and were even born there, but due to legal issues and lack of interest, they did not apply for Mexican citizenship. For their part, the Kumiai population in sjz and saint self-identified, and was also recognized by the Russian and Mexican population, as "Indians". The Kumiai population referred (to this day) to the "mestizo" population as "Mexican" and subsisted mainly on hunting, fishing and gathering;9 sometimes adult males were employed as day laborers and cowboys on nearby ranches and in the cr. From the very beginning, the agrarian authorities urged the population of sjz to join the ejido as an "annex".

The parties affected by the possible expropriation in order to establish the ejido's legal boundaries pointed out certain irregularities in the initial request, such as the fact that there was no previous settlement whose inhabitants had organized to found this agrarian nucleus. The representatives of the affected ranches denounced that the school located on the cr as the most inhabited and important place in the valley. They added that the population of this colony did not have Mexican nationality, so they had not taken any steps to receive an ejido endowment. There was also non-compliance with the requirement of at least 20 agrarian right holders in the previously existing settlement, since, according to the non-conforming party, the agrarian census registered people from outside the area who did not meet the six months of previous residence. As a measure of détente, seeking to save most of their land, the owners of the Bella Vista ranch proposed to the Governor of the Territory and the authorities of the Agrarian Department to dispose of 575 hectares of the "Cañón del Trigo" area.10 located to the northeast of the property. The land was fertile clay soil, wedge-shaped between granite mountains, suitable for growing wheat and with access to a spring.11 Perhaps due to the defense of the landowners, the San Marcos ranch was no longer contemplated for the land appropriation (although it was expropriated in the subsequent expansion of the ejido) and only the Bella Vista ranch remained as a target. Initially, it was proposed to take 2,500 hectares of this property, but in the end only less than half of that area was affected.12

For his part, on October 18, 1937, the vocal secretary of the Agricultural Executive Committee of ep transmitted to the governor an agreement adopted at the ejido's General Assembly to protest the "acts" of the cr They claimed that they contravened the government's "social program" and asked for support to stop the hostility. They accused this "foreign colony" of representing a "danger", of having insulted them and prevented them from passing through their property, in addition to the fact that an army captain confiscated "quite a few weapons" from the Russian population.

At the beginning of 1938, it was decided to provide ep Provisionally, while it was being ratified by federal authorities, 2,920 hectares of uncultivated land was divided into 59 plots of 20 hectares each, distributed among 58 qualified individuals according to the agrarian census, plus one lot destined for a school plot and 1,740 additional hectares for the collective needs of the ejido. From the Bella Vista property, 1,180 hectares were taken, while the remaining 1,740 hectares came from national lands. Later, in 1959, an ejido expansion was approved, this time at the expense of the San Marcos ranch and national lands.

The ejido's population agreed to maintain the local roads under their jurisdiction in good condition, which was a common practice in the region's rural areas. The community of sjz in the ejido endowment as a measure to ensure that their lands were respected, since the end of the 20th century. xix, They faced threats from private individuals due to the lack of legal titles, which put them at risk of having their lands classified as "national". The governor verbally agreed with the Kumiai community that their lands would be incorporated into the ejido for their own use. Alberto Emes, "captain of the Indians" from sjzThe community's representative on the ejido oversight committee. Without ignoring the interest in legally protecting the Kumiai lands, the fact is that confining the native populations to the ejidal regime was a State strategy to "campesinize" the native populations in order to complete the cultural mestization.

Community organization and social change

The ejido's hamlet was established on the banks of the road to Ensenada, in the El Tigre area, which, according to the engineer in charge of the demarcations, seemed "almost a continuation of the Russian Colony settlement". The one-hectare housing lots were assigned by lottery. Some of the old adobe buildings belonging to the Bella Vista ranch built between the end of the century xix and early xx were rehabilitated to house ejido families. The school-age population, 20 children, were sent to the school of the cr while they built their own campus. After a few months, ten of the ejidatarios resigned and were soon replaced by the same number of people. The Agrarian Commission representative disqualified those who left the ejido, stating that their departure was because they were not farmers and could not bear the "sacrifices inherent to the organization of the work"; he accused that some of the deserters had tried to "dissolve the ejido". The Agrarian Commission reported that the substitutes joined with their families, bringing with them farming equipment, horses, pigs, goats and chickens, and with a willingness to settle in tented houses, work without support from the ejidal bank and support "the ejidal society". The emphasis on these aspects reflects the political and social imaginary of the authorities, who valued sacrifice and a cooperative attitude among the beneficiaries of the agrarian distribution.

The engineer in charge of the boundary delimitations stated that in principle the cr was "nervous" about the fear that "some ill-intentioned people" sowed in her, but that she had returned to "relative tranquility". What was said in this report coincides with what was mentioned by Candelario Carreon and others. The engineer reported to his superiors that since the previous decade, Russian families had been emigrating to usaHe added that the phenomenon intensified after the ejido was founded. The engineer added that the younger people left the colony due to the "lack of entertainment" and in search of a better life in the neighboring country, so that only the older people remained in the colony.13 In fact, one of the immediate effects on the cr The main reason for the formation of the ejido was to be deprived of access to the affected area of land, which they had been leasing since their arrival in the area. vdg The second factor was the alteration of the social and cultural environment, as they were exposed to coexistence with the people of the ejido. A second factor was the alteration of the social and cultural environment as they were exposed to coexistence with the people of the ejido. Nevertheless, some Russian farmers leased ejido land after a certain period of time. For example, in 1945, Pablo Rogoff and his family lived within the ejido perimeter,14 despite contravening the agrarian law.

The engineer informed his superiors that the heavy rains hindered his work and left the roads in poor condition, which is why he was unable to leave the ejido until two or three days after completing his work. At various times, the population of the vdg has been cut off from communication and its crops have been damaged by floods, landslides and deterioration of the roads due to the flooding of the river, streams and lagoons. The most significant climatic calamities include the years 1939-1941, 1978-1982 and 1993. In reference to the mishaps caused by the rains, Candelario Carreón [pho-e/1/37(1)] indicated that when it began to rain on the first day of May 1940 or "41",15 at first believed that it would benefit their wheat crops, which were gleaning at the time, but a gentleman by the name of Cosio, whom he alluded to as one "of the natives" (i.e., a resident of the vdg Carreón warned them that the rain would bring chahuistle, a fungus that makes wheat sick, which was true. Carreón said that they had planted wheat at the behest of the ejido bank because that institution would only refinance and credit wheat and barley crops, despite the fact that the ejido wanted to plant vines and olive trees at the suggestion of "the natives". To deal with the plague, the bank suggested that they pack it and sell it as fodder, but they did not find buyers because not even the cattle would accept this product as food. This situation led some people to abandon the ejido, which was one of the reasons for the withdrawal of a group of inhabitants in the initial stage.16 Carreón indicated that the ejidal bank recommended using a "pink powder" to treat the wheat and thus they recovered part of the crop. The adverse situation led them to try barley crops provided by the owner of the "Tecate brewery".17

From late 1978 to 1982 there was a cycle of heavy rainfall in the region that replenished the groundwater table in the vdgwhich since the beginning of the 1970s had been suffering from depletion and high salinity due to overexploitation and droughts (interview with Joaquín Alves [pho-e/1/35(1)]). In 1978 the Guadalupe River overflowed its banks and the town was cut off. To help the people of the ejido cross the river and break the isolation, workers from the Olivares Mexicanos company,18 most of whom came from the ejido and the neighboring town of Francisco Zarco [hereafter fzIn January 1980, the river flooded and the population was cut off for several days. In January 1980, the flooding of the river cut off the population for several days. Due to the floods fz was relocated to a higher surface (where it is currently located).

Government intervention in the public life of the ejido was crucial to strengthen the State's corporate control and reinforce the model of national identity proposed by its institutions. In this sense, Mariana Ramírez [pho-e/1/24(1) and (2)] recalled that a teacher named Güirola, originally from El Salvador, attended the elementary school in the ejido and was in charge of organizing the patriotic celebrations with dances, poetry and plays. The teacher urged the women to form a "Women's League" to assist the sick, especially since there were cases of tuberculosis. This speaks of the active role of the women in the ejido, as they carried out surveillance patrols, made representations to the municipal president of Ensenada (to whose jurisdiction the ejido belonged), and took part in the activities of the women's league. ep) to build the first ejido store and in agricultural work. In Mariana's words, the professor taught them how to manage the store; however, the store and the women's league only lasted about two years due to the disinterest of the ejidatarias. Despite their participation in public and private tasks, until approximately 1965 Juana Cariaga, head of household while her husband worked in usawas the first woman to be recognized as a holder of agrarian rights (information provided by her son Victor Bravo Cariaga, [pho-e/1/35/(1)].

The nationalist ideology of the Mexican Revolution had in the ejido one of its strongholds; it was the main instrument of agrarian distribution and a means of transmission and exercise of the hegemonic national project. It is in this context that the memory of Mariana [pho-e/1/24(1) and (2)] about the saying of the men from ep The ejidos did not allow churches or visits from religious ministers because they advised the ejidatarios to leave the land because it was not their property; hence, on one occasion an ejidatario chased a priest who had come to officiate mass from the town. In the ep The commemorations of national independence, the Cinco de Mayo battle and the Mexican Revolution opened spaces for staging to promote the nationalist project and inculcate a model of citizenship in line with the regime:

the ejido began to form, to form commissions, there were meetings all the time, even at night. There was a Salvadoran teacher, Víctor Güirola [...] he was one of those who was stirring up communism at that time, so he organized us, he helped us because he was the teacher [...] ah, but when we arrived here we arrived in August [1939] and we celebrated September 16, well, we all paraded and there was nobody to look at us! (Interview with Pedro Carreón, in Ensenada, 1999: 675-676).

In the early 1930s, Gilberto Loyo, demographer, political scientist and ideologist of the regime, pointed out that in order to alleviate the "lack" of "identity" elements, public school teachers had the task of (re)affirming the attributes of "Mexicanness", with special emphasis on the northern border (1935: 383). In epThe performative exaltation of Mexican elements was a determining criterion at the moment of choosing a "queen" to lead the patriotic parades:

the first party I remember was on September 16, 1938 [...] oh well, we were just a handful of people! Professor Víctor Güirola was there [...] then he said, "we are going to have a queen" [...] There was a cart without an awning [...] they said "well, here we are going to walk her", through which streets if there weren't even people? [...] The teacher liked that she [one of the ejidatarios' daughters] was [the queen] because she represented, because of her long hair, and she wore very thick braids, they said "she can represent a Mexican". As we had nothing [...] until the following year we started to make our skirts of china poblana and we embroidered them with chaquira, sequins, we made our shirts and we said we had parties, but she was the first, a Mexican [...] to lead the parade (Interview with Silvia Lugarda, in Ensenada, 1999: 679-680).

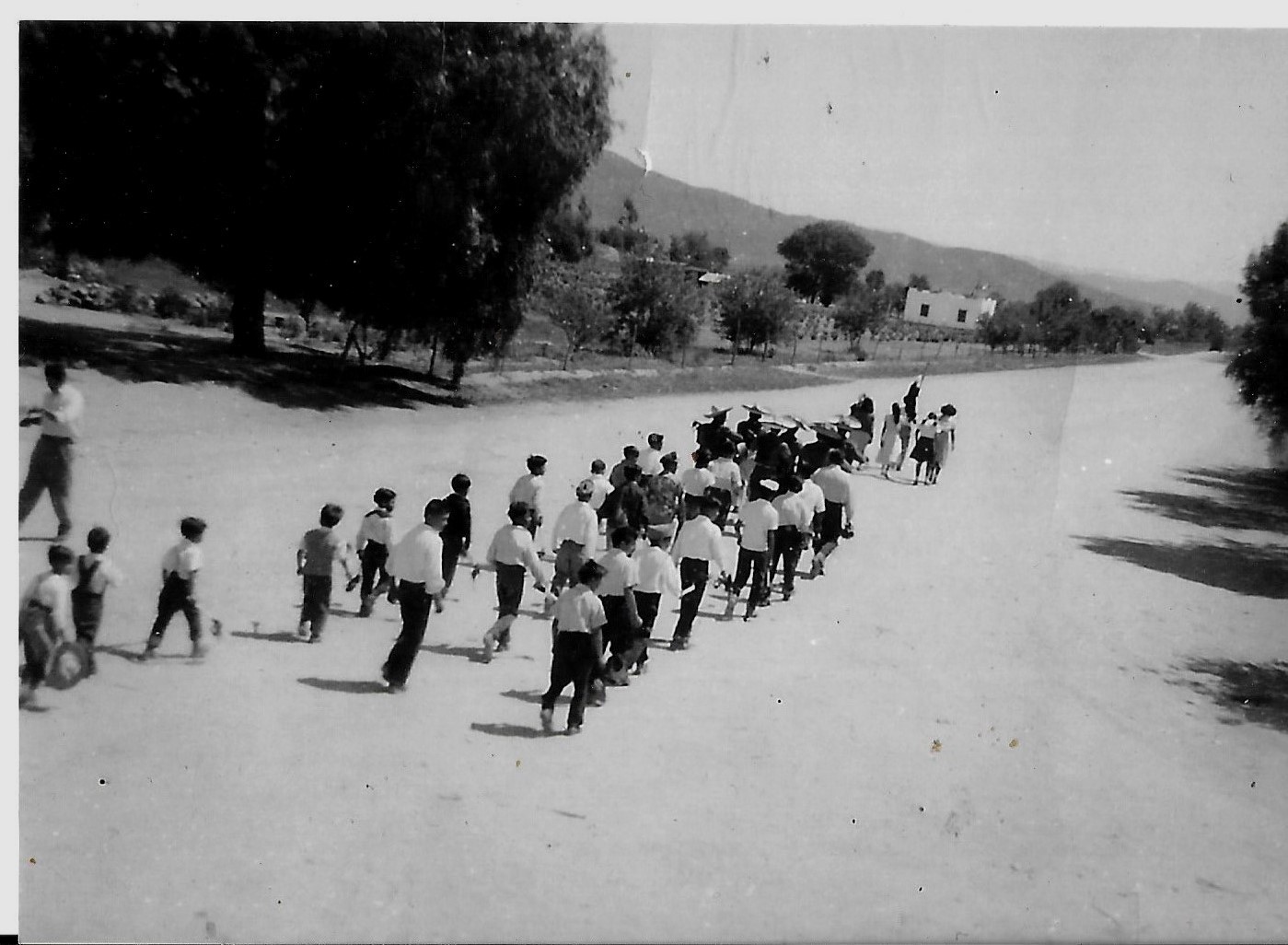

After a while, the "queen" destined to lead the patriotic parade was no longer selected, but the one who sold the most "votes". In one of the events held in the 1960s, "Srita." Yolanda Portillo participated as a "candidate" [sicTo achieve his goal, he sold vouchers equivalent to 10 votes at the price of one peso.19 The patriotic procession included a contingent from the local elementary school that also led a "queen" guarded by her "princesses", all of whom were chosen from among the students. Photographs from the 1940s and 1950s show the progress of the parade on the wide dirt road that crossed the ejido, made up of groups of men and women, young people and school-age children, some of whom were dressed in mariachi costumes.20 Students of Russian origin also marched in the processions.

Social activities in the ejido were key to the articulation of the sense of belonging and community affiliation of its inhabitants. Life became more diverse and entertaining. In addition to the genuine concerns of the community, the Mexican State was interested in strengthening community identity in accordance with the national project based on national affiliation, civic loyalty and civic commitment. Images from the 1940s show baseball and other sports involving uniformed Mexican military personnel and the presence, at least as spectators, of young Russians.21 The 1960s saw the emergence of musical groups in genres such as mariachi, rocanrol and pop. In the 1970s, a cowboy club was formed to compete in regional events.22 At that time it was in session in ep the "Masonic Lodge number 5", with a membership of between 20 and 25 members, some of them residing outside the village (interview with Maclovio Rodriguez [pho-e/1/32/(1) y (2)]).

During the first half of the xx the crops of the vdg depended on rainwater; only the orchards were irrigated from a few water wells. The transition from the traditional wheat, barley and alfalfa crops to vineyards to supply the region's growing wine industry fostered economic and other dynamics that connected the ejido with diverse economic actors. This is evidenced by the "Harvest Fair", whose first edition was held in 1963 in the ejido.23 In October 1964, a poster with the logo of Cerveza Mexicali, promoted the candidacy of "Srita." Anita Carreón for "queen" of the festivities of the ii Harvest Fair to be held at the vdg. In the fifth edition, corresponding to 1967, several young women competed for the title of "queen" and "princesses" of the festival.24 The plasticity and performativity deployed in these leisure, consumption and entertainment activities formed a collage of popular representations associated with "Mexicanness". For example, in a 1964 photograph of the second Harvest Fair, a man and two young women wear "Aztec" style attire. In the 1970s, the Harvest Fair gave way to the "grape harvest festival". In another edition, held in the ejidal park, Enrique Guzmán, a singer from the Televisa company, performed, indicating that the festivity had reached a certain size.25 The Pedro Domecq winery, located in the vdg in 1972, organized its own celebration (El Heraldo de Baja California, 1972: 6a).

Agricultural changes, labor and water

The competition generated between ep and the cr The competition for access to land, the use of water and the availability of agricultural credit increased through the technification of crops and the shift towards more profitable crops. The cr took the first steps to introduce changes and adaptations through pumping equipment, irrigation equipment, technical advice and financing (see Dewey, 1966; Kvammen, 1976). From an early stage in ep had the support of the agrarian and credit institutions of the Mexican State, but the difficulties involved in a new population settlement conditioned the adaptation and changes in production. In the 1960s, the traditional crops of wheat and barley gave way to alfalfa, grapes and olives, which found a better national and regional market, as well as technical and financial support from the government and industry. Between the 1960s and 1970s, the following were installed in the region vdg companies with greater economic, technical and commercialization resources. At that time, winemaking gained economic, social and cultural preponderance.

On July 10, 1958, the social dynamics of the vdg was disrupted when groups of land claimants from other parts of Baja California and the country took over the land plots of the cr and other properties with the support of the then governor of the state, Braulio Maldonado. These events resulted in the formation of the town of fz. As Maldonado stated in his political memoirs (1993: 127), he aspired to convert the vdg The region has become the "largest olive and wine industry center in the American continent". As early as the late 1950s, at the behest of the federal and state governments, the installation of agro-industries dedicated to the cultivation of alfalfa, olives and grapes was encouraged. The diversification and intensification of the economic activities in the vdg Some of these people settled in the ejido, without agrarian rights, with the endorsement of the ejidal authorities and the community through a series of agreements between individuals in terms of leasing, buying and selling, concession or loan of plots or fractions of land.26 At the end of the 1980s, more people arrived, linked to the hotel and catering industry, winemaking and other agricultural activities [interview with Pablo Ruiz pho-e/1/28(2)].

Economic changes had an impact on the labor market. In the 1960s, the inhabitants of the fz organized themselves into unions affiliated to the large pro-government labor centers in order to secure access to available jobs over their counterparts in ep, sjz and saint. The unions controlled the filling of vacancies by rotating vacancies among unionized personnel every few years. The ejido also became unionized, so that during those years there was a headquarters of the Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Industria Olivarera Similares y Conexos, affiliated to the Confederación de Trabajadores de México (Confederation of Mexican Workers (ctm).27

A crucial issue in the vdg The main problem has been water shortages since the 1960s and 1970s due to droughts and overexploitation of aquifers. In 1964 the federal government restricted indiscriminate and uncontrolled water extraction, a measure that had been recommended since 1941. The dispute over water intensified because of the use of the liquid available in the vdg to supply the fish processing industries of the neighboring town of El Sauzal, located some 20 km to the west. In 1960 Juan Rodríguez, son of the former governor of Baja California and former president of the republic, General Abelardo L. Rodríguez, as the owner of a canning company, illegally built a 34 km long aqueduct to carry water from the vdg to his company. To mitigate tensions with the local population, where part of his company's workforce came from, particularly the fzwater was distributed to their homes by means of pipes [see interview pho-e/1/31(1)].

At present, the vdg is a tourist and agricultural enclave dedicated to wine and gastronomic activities with a rural profile that attracts thousands of visitors. These dynamics have encouraged disputes over the management of natural elements, changes in land use, the flow of capital, development plans, population growth and identity tensions. Community relations in ep are disrupted by the antagonisms arising from the management and control of available resources and the pressures of external economic agents seeking access to the use of ejido assets and commercial opportunities. At present, the future of the ejido looks as uncertain as it has been under neoliberalism for so many of Mexico's agrarian communities.

Abbreviations

cr Russian Colony

ep El Porvenir

fz Francisco Zarco

usa United States of America

Ha Hectares

pho Oral History Project

saint San Antonio Necua

sjz San José de la Zorra

vdg Guadalupe Valley

Files consulted

Archivo de la Palabra, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (ap iih uabc), Tijuana, México.

Archivo Judicial de Ensenada, en Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (aje en iih-uabc), Tijuana, México.

Registro Agrario Nacional (ran), Archivo General Agrario, Ciudad de México.

Bibliography

Billig, Michael (1998). “El nacionalismo banal y la reproducción de la identidad nacional”, Revista Mexicana de Sociología, vol. 60, núm. 1, pp. 37-57.

Burton, Antoinette (ed.). (2005). “Introduction. Archive Fever, Archive Stories”, en Archive Stories. Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History. Durham/Londres: Duke University Press, pp. 1-24.

Dewey, John (1966). “The Colonia Rusa of Guadalupe Valley, Baja California: a Study of Settlement Competition and change”. Tesis de maestría. Los Ángeles: California State College at Los Ángeles.

Diario Oficial. Órgano del Gobierno Constitucional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (1936). xcvii (52), México.

El Heraldo de Baja California (1972). Tijuana.

Fabila, Manuel (1941). Cinco siglos de legislación agraria en México (1493-1940). México: Registro Agrario Nacional, pp. 482-549.

Kvammen, Lorna (1976). “The Study of the Relationships between the Population Growth and the Development of Agriculture in the Guadalupe Valley, Baja California, Mexico”. Tesis de maestría. Los Ángeles: California State University of Los Ángeles.

Loyo, Gilberto (1935). La política demográfica de México. México: Secretaría de Prensa y Propaganda del pnr.

Maldonado, Braulio (1993). Baja California (comentarios políticos). México: sep/uabc.

Paul, Herman (2016). La llamada del pasado. Claves de la teoría de la historia, traducción Virginia Maza. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando El Católico/Excma. Diputación de Zaragoza.

Peña, Moisés T. de la (1950). “Problemas demográficos y agrarios”, Problemas Agrícolas e Industriales de México, México, ii (3-4).

Robinson, Craig (2005). “Mechanism of Exclusion. Historicizing the Archive and the Passport”, en A. Burton, Archive Stories. Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History. Durham/Londres: Duke University Press, pp. 68-86.

Ruiz Ríos, Rogelio Everth (2023). “Salidas de la aporía: enfoques y perspectivas en la historia después del giro lingüístico”, en Miguel Ángel Gutiérrez y Guillermo Rodríguez (coords.). Formas de ver y escribir la historia. Experiencias y preocupaciones historiográficas contemporáneas. Morelia: Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, pp. 36-60.

— (2022). “Utopía, mesianismo y milenarismo en Tomóchic y Canudos”, Relaciones. Estudios de Historia y Sociedad. Zamora, pp. 119-139.

— (2020). “Dos temas paralelos al auge de la historia del tiempo presente: el tiempo histórico y las relaciones entre historia y memoria”, en Eugenia Allier et al. (coords.). En la cresta de la ola. Debates y definiciones en torno a la historia del tiempo presente, México: unam, pp. 93-113.

— (2008). “De colonos prósperos a extranjeros reticentes. Rusos molokanes en el Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California, 1906-1958”. Tesis de doctorado en historia. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán.

Samaniego López, Marco Antonio (1999). Ensenada, nuevas aportaciones para su historia. Mexicali: iih, uabc.

Schmieder, Oskar (1928). “The Russian Colony of Guadalupe Valley”, Lower Californian Studies, ii (14). Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 409-434.

Traverso, Enzo (2007). “Historia y memoria. Notas sobre un debate”, en Florencia Levín y Marina Franco (comps.). Historia reciente. Perspectivas y desafíos para un campo en construcción. Buenos Aires: Paidós, pp. 67-96.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (2017). Silenciando el pasado. El poder y la producción de la historia. Traducción Miguel Ángel del Barco. Granada: Comares.

Wallis, Eileen (2010). Earning Power: Women and Work in Los Angeles, 1880-1930. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

Entrevistas (ap iih uabc)

Álves Iglesias, Joaquín, entrevista realizada por Bibiana Santiago y Carlos Alberto García Cortés, instalaciones de Formex Ibarra, 28 de febrero de 1997, pho-e/1/35(1).

Bravo Cariaga, Víctor, entrevista realizada por Bibiana Santiago, El Porvenir, 14 de febrero de 1997, pho-e/1/35/(1).

Carreón Gutiérrez, Candelario, entrevista realizada por José Luis González López y Carlos Alberto García Cortés, El Porvenir, 1997, pho-e/1/37(1).

García, Alfonso Remigio, entrevista realizada por Carlos Alberto García Cortés, El Porvenir, 24 de enero de 1997, pho-e/1/30(1).

Peralta García, Juan, entrevista realizada por María Jesús Ruiz, El Porvenir, 1997, pho-e/1/31(1).

Ramírez Rodríguez, Mariana, entrevista realizada por María Jesús Ruiz, El Porvenir, 17 de enero de 1997, pho-e/1/24/(1) y (2).

Rodríguez Melgoza, Maclovio, entrevista realizada por Bertha Paredes Acevedo, 22 de enero de 1997 y 14 de febrero de 1997, pho-e/1/32/(1) y (2).

Ruiz Madrigal, Pablo, entrevista realizada por Bibiana Santiago Guerrero, El Porvenir, 7 de febrero de 1997, pho-e/1/28(2).

Electronic resources

Legislación preconstitucional de la Revolución (1915) [https://congresoweb.congresojal.gob.mx/bibliotecavirtual/libros/LegislacionPreconstitucional1915.pdf]

“Porvenir memoria fotográfica” [https://www.facebook.com/PorvenirMemoriaFotografica].

Rogelio E. Ruiz Rios is a researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas of the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. D. in History from El Colegio de Michoacán. Member of the National System of Researchers (sni) of the conahcyt level i.

Research topics: recent historiographical trends, tensions between history and memory, history and post-humanisms, colonization and occupation in Baja California, communities, utopias and futures.

Research networks: Present Time History Network, Research Network on Communities, Futures and Utopias of the Latin American Anthropology Association, member of the Communities and Futures Project of the Frontier Science call of the Latin American Anthropology Association. conahcyt for the period 2023-2025.