The methodology is movement. Proposals for the study of the urban experience of transit supported by the use of the image

- Christian O. Grimaldo-Rodríguez

- ― see biodata

The methodology is movement. Proposals for the study of the urban experience of transit supported by the use of the image

Received: February 14, 2018

Acceptance: May 31, 2018

Abstract

I present a methodological strategy aimed at understanding and analyzing the objectified and internalized forms of the city from the experience of transit. The tools that I share consider two fundamental expressions of experience: practical-experiential and imaginary-referential. I emphasize the key role played by the collaborative and dialogic approach supported by the use and creation of images to understand the experience of passersby.

Throughout the text I show some interpretive sketches to show the analytical possibilities of the method that can be used to identify the overlaps between the city practiced, perceived and imagined by various passers-by, in this case users of public transport in the metropolitan area of Guadalajara.

Keywords: visual anthropology, urban imaginary, collaborative methodology, mobility, psycho-geography

Methodology is movement: image-use-supported proposals for studying the urban transit experience

I present a methodological strategy that seeks to understand and analyze the city's objectivized and interiorized forms, based on the transit experience. The tools I share take up two of the experience's fundamental expressions: related to life-practice and the imaginary-referential. I emphasize the critical role collaborative and supported-dialogic approximations play in using and creating images to understand the transit experience.

Throughout the text I present interpretive models to demonstrate analytical-method possibilities that can be used to identify overlap between the way a variety of those in transit — in this case, metro guadalajara's public-transportation users — interact with, perceive and imagine the city.

Keywords: collaborative methodology, visual anthropology, mobility, urban imaginaries, psycho-geography.

There is no definite map for those endless transfers,

where the means of transport is

more meaningful than the environment.

Juan Villoro

Oblivion: an urban itinerary.

First location: the origin of a question when traveling

I structure this article based on the similarity of a methodological strategy with a path that is traveled, sometimes in a sinuous way and many times with unexpected turns. Thus, I describe five different locations and their consequent displacements originated from the need to give logic to research practice in the urban environment. With this I seek to account for the way in which the methodology in urban anthropology needs to be, in itself, a movement. As will be seen in the following sections, what began as a study on the practical and experiential experience of traveling turned towards an inquiry into the symbolic experience of said practice, for which the use of the image became key as part of a comprehension strategy. The reason for such a turn was produced by the same experience of walking through the city with an anthropological gaze guided by the gazes of everyday passersby.

The first location that I present here coincides with the origin of my interest in studying the relationship of daily traffic with the ways of being, practicing and imagining the city, it was born in the most unexpected but perhaps most appropriate way possible: while traveling in a public transport vehicle in the city I live in and through which I have traveled since my childhood.

Like the millions of people who live in the Guadalajara metropolitan area (amg) and many others who reside in cities, I have found myself in the need to move between different parts of it to develop as a person.1 Public transport was –from adolescence and for most of my life– the most affordable way to get around and carry out study and work activities to which I owe the opportunity to be writing these types of reflections today.

On one of those seemingly insignificant and tedious journeys, one rush hour morning, I realized that there were certain recurrences in what I perceived day after day as part of my daily life in the city. In a small moment of strangeness, I seemed to perceive a relationship between the industrial landscapes through which the public transport route traveled and the faces, ways of dressing, speaking and even thinking of those of us who commuted daily on that same road. People who looked like workers got off the bus where there were industries, people who looked like clerks got off where there were executive-looking buildings, people who looked like students left where they could transfer to their schools. So I had my first two questions, perhaps just as complex: "What will I look like?" and the second "would traveling through the same places every day influence in any way the way in which those of us who traveled in the public transport vehicle perceived ourselves and the city?" I felt the imperative need to talk with other travelers about this, but at first it seemed to me that I could not do it, because for this I would have to start a conversation with strangers and I knew, implicitly, that this should not be done in public transport.

I narrate this preamble as an introduction because it was the need to enter into dialogue that led me to propose the methodology that I present in this article, as a possibility to identify objectified and internalized forms of urban space in the experience of passers-by and transport users public. The first dilemmas I faced were to think about how to study what I myself was a part of and in what terms could I construct a horizontal definition of what seemed to me to be a principle of the order of urban life that is created and re- creates every day from the practices of those who walk through the city.

This reflection is directly related to the discussion of horizontal methodologies (Corona and Kaltmeier, 2012) because the dialogue with users of public transport allowed me to develop a methodological strategy that could account for the intersubjectivity processes that underlie the experience of transit through the city. city. For me, the encounter with the experiences of others who travel the same city as me, represented the opportunity to see, as in a mirror, the collective face of which I am a part as a resident of the same city that I study. At the same time, it allowed me to discuss my own conceptions of urban space and the people who produce it.

I return to my research practice to discuss the way in which, when studying topics related to movement, curiously, the methodology of my study itself was formed in movement; as described by Corona and Kaltmeier (2012) when referring to the particularities that horizontal methodologies acquire, due to their interest in studying social processes rather than defining truths or certifying researcher preconceptions.

The objective I pursue is to show a methodological proposal that incorporates various visual tools for the dual understanding of the experience of traffic. I consider that the use of photography and cartography, as a complement to the ethnographic approach to the study of traffic, enables analytical perspectives that show the process of social construction of the city in its practical, physical and symbolic complexity.

Second location: experience as a vehicle to understand the urban

Once I was certain about the relevance of approaching the study of the correlation between the city and pedestrians as an object of anthropological study, it was necessary to identify a comprehensive access door that would allow me to develop a methodological strategy. It seemed to me that the ideal thing would be to approach this phenomenon by means of the systematic study of the experience in the plane of the daily life.

Here I will take by experience the accumulation of knowledge about the social world acquired through personal experience and / or social reference, which in turn serve to guide the practices and meanings that we attribute to our daily lives. Alfred Schütz resorted to a typification similar to this to refer to the act, defined as “an experience installed in the available knowledge repository of something concrete, be it real or imaginary” (Schütz, 1932: 60). This means that, from this type of perspective, there are two ways of acquiring knowledge about the social world that guide our actions in everyday life: through immediate experience and practice or through imaginary contextual reference; the first nurtured mainly by personal experience, the second by the historical-cultural framework.

Considering the role of the imaginary as constitutive of the referential experience is essential, especially in terms of the urban. In the words of García Canclini (2007: 91), “the imaginary refers to a field of images differentiated from the empirically observable. Imaginaries correspond to symbolic elaborations of what we observe or of what frightens us or we wish it existed ”. This means that, despite the fact that they are differentiated elements from what is empirically observable, it is not something alien to empirical experience, on the contrary, as Hiernaux and Lindón well recognize, it is “an acting force, not a simple representation, a way of assimilating the lived reality and acting on it ”(2007: 158).

Thinking about the duality of the experiential / referential experience entails assuming that such knowledge is interwoven, so that personal experiences nourish social references and these in turn can precede and outline the type of personal experiences; it is a continuous dialectic that orders our being and being in the plane of daily life. Understood in this way, the experience outlines the type of approach that people have with reality, as well as the desire or avoidance that we have regarding certain practices, people, relationships, objects and places in the city.

The urban environment is a network of social, architectural and symbolic relationships. Such attributes constitute cities in a conglomerate of socializing structures that order and shape the people who practice them on a daily basis. The city does not model people in the manner of a higher entity, but rather through the intersubjective framework that precedes their individualities, produced and reproduced through their own practices in daily life, sustained in turn in the sense that people give them. Hence, Fernández Christlieb (2004: 14) affirms that “the human being is strictly being urban, because humanity is first of all urbanity”.

It is because of the above that various authors have proposed to think of the city from its characteristic collectivity, either as a way of life (Wirth, 1938), a state of mind (Park, 1999), a thought (Fernández, 2004) and, even a bodily experience (Sennett, 1997). In any case, it is about appreciating it as a collective process, intervened by a series of common interactions and not as a sum of material elements or a mere scenario in which individual behaviors occur.

In order to analytically approach the experience, both experiential and referential, of those who pass through the city, I resorted to the ideas of social constructionism proposed by Berger and Luckmann (2006), from which the process of objectification of urban reality can be analyzed in the world of everyday life. Thus, the social, physical and mental spheres that constitute urban life can be visualized as a continuum articulated, in which walking represents a device of constant internalization of forms, norms and symbols. When traveling we learn, reinforce and / or refute referential experiences, through personal experience; which constitutes a dialectic between what is lived and what is referenced described by authors such as Castoriadis (2013) in terms of the dialectical process between what is instituted and what is institutionalized that configures change and the permanence of society.

I recover the emphasis that Berger and Luckmann (2006: 37) put when considering everyday life as “the reality par excellence”. For them, everyday life is the reality from which we articulate our thoughts and actions regarding the social world in which we develop. This means that it is from the daily experience that people perceive, interact and internalize the city, with which we also constitute ourselves as urban beings, while reproducing the urban order that gives meaning to cities.

Berger and Luckmann proposed a conceptual apparatus interested in knowing the way in which reality is socially constructed. For them, "the man in the street lives in a world that for him is 'real', although to different degrees, and 'knows', with different degrees of certainty, that this world has such or such characteristics" (2006: 11 ). For this reason, they argued that the sociology of knowledge should focus above all on “what people 'know' as 'reality' in their daily lives” (p. 29). They recognized this type of knowledge as common sense knowledge and in it they located the type of knowledge “without which no society could exist” (Berger and Luckmann, 2006: 29).

The experience of everyday life has been a recurrent axis of theoretical articulation in the study of the physical, social and mental spheres of cities. Either to work with space, landscape and territory (De Castro, 1997), to locate the plane where people present their actions through interactions (Goffman, 1997) or to discuss the formation and action of urban imaginaries (Ortiz, 2006 ). Hence, for example, proposals to ethnograph places such as that of Vergara (2013) resort to the everyday as an articulator of the itineraries and routes that people practice on a micro (home), meso (meso) and macro (city) scale. .

In the specific case of the transit experience, multiple methodological efforts have also been developed, from which my proposal derives. Such is the case of what Büscher and Urry (2009) recognize as mobile methods, a product of what they identify as a “shift towards mobility”, characterized by the identification of new study entities in the field of everyday life. The proposal of such methods aims to consider the value of the multiple, the chaotic and complex that occurs in the space between here and there that usually represent the origin and destination of the geographical points where the anthropological study scenarios are located. For this type of proposal, the path itself is the object of study.

For Büscher and Urry (2009) the research methods are assumed to be mobile in two senses; on the one hand, there are those who seek to follow the interdependent and intermittent forms of the physical movement of people, images, information and objects (Sheller and Urry, 2006); and on the other, those who seek to tune into the social organization of the movement, as a consequence of moving with and through the research collaborators. In this second case, it is about investigations on how people, objects, information and ideas move and mobilize in interaction with others, which reveals a grammar of the social, economic and political order (Sheller and Urry, 2006: 103). What is interesting about these two senses is the description and analysis of the methods that people use to achieve and coordinate orientations and norms in the social world through which they pass.

Among the most common ways to practice these methods is the practice of following people in motion using techniques such as shadowing or shade (Alyanak et al., 1980), in order to identify their relationships with places or events during their journeys through the city. As an example of this type of exercise, the work of Jirón and Mansilla (2014) can be consulted, in which they use shading to account for the consequences of fragmented urbanism in the daily life of passers-by in the city of Santiago de Chile.

There are also techniques focused on participating in movement patterns while the research is being carried out, such as walking accompanied (Morris, 2004) unlike shading, this tool implies a more direct relationship with research collaborators, through immersion in their worldviews . It is usually characterized by including interviews that take place during the journeys, in which detailed descriptions of what is perceived, felt and meant by research collaborators are sought. These types of tools are basic, but they become more complex according to the needs and anthropological questions of the research, in some cases involving the use of technological, visual, textual or cartographic tools, as in the work of Büscher (2006) on the perception and intervention of the landscape in the UK.

A methodological strategy to study traffic and its ordering meaning in urban life may vary in terms of the techniques used, but I suggest that these be articulated around the approach of the three key spheres in which the experience occurs: the material, corresponding to the experience of the perceived; the social, linked to the experience of what is practiced; and the symbolic, linked to the experience of the imagined. The three spheres are intertwined in a co-constitutive way and can only be separated in analytical terms, since, in reality, they occur and exist as the same phenomenon.

I propose to consider these three spheres based on what was proposed by Henri Lefevbre, who considered the existence of three types of space: 1) the perceived space (real-objective), 2) the conceived space (of the experts, scientists and planners) and 3) the lived space (of the imagination and the symbolic, within a material existence).2 I return to the expression of this triallectic to account for the process by which individuals internalize the city they practice, but in this case I am interested in thinking more in terms of experience than space; Therefore, I choose to speak of what is perceived, what is practiced and what is imagined. I use different adjectives to define experience because I consider, for example, that speaking of the space conceived as the space of the experts passes to a different analytical plane than the one I am interested in showing here. Another reason I pursue is to avoid the problems that the similarity of the adjectives "perceived" and "conceived" as they are translated into Spanish from Lefebvre's original proposal can engender; For practical purposes, it seems to me that it is better to talk about what is perceived, what is practiced and what is imagined hand in hand with experience.

To address the three aforementioned spheres, I propose: 1) the reading of the urban landscape by systematically registering its regularities during transit from strategic routes; 2) the practice of urban transit to recognize the ritual patterns, codes and norms of interaction typical of daily life from movement; 3) the externalization and objectification of those elements of urban life that passersby keep internalized as part of their urban imaginations, and 4) the definition and sharing of the experience and meanings attributed to the city from the point of view of their own passersby.

In the following sections I present some of the situations that gave rise to the methodological strategy that I have discussed, as well as some reflections on the techniques used to record the experience of traveling. I emphasize the type of information that emanates from its uses and the way in which two different types of experiences intersect in the same task of the researcher: that of the observing passerby and that of the everyday passerby. The researcher who studies the daily traffic is above all a passerby and that entails various challenges and virtues in the investigation.

As will be seen, the study and analysis of the experience of the transit from ethnographic tools, in my case, resulted in the need to think and typify the diversity of the experience beyond its experiential side, to think about its referential components. This means that not all experience is defined in personal and / or individual terms, but that many of the times the social-referential experience outlines and filters such types of experience when passing through. The use of the image became key to better understand how both types of experience are articulated in everyday life. This occurred above all from the recognition of the role that appearance and perception play in the experience and social categorization of passersby, which will be seen in the following sections.

Third location: the city perceived and practiced (the observation in transit and the semi-structured interview)

In my case, and very probably in that of many students of urban culture, observation serves to re-know the city that one practices and in which one has been socialized. The re-knowledge implies the possibility of re-knowing aspects of urban life from a strange and necessarily curious look (never from scratch), so that the observation and the records that derive from it problem and destabilize the normalized look of the researcher. I will refer to this exercise as observation in transit, without intending to add yet another technique to the already extensive drawer of the existing multiples, but to emphasize that, in this case, participant observation requires transit as an articulating logic.

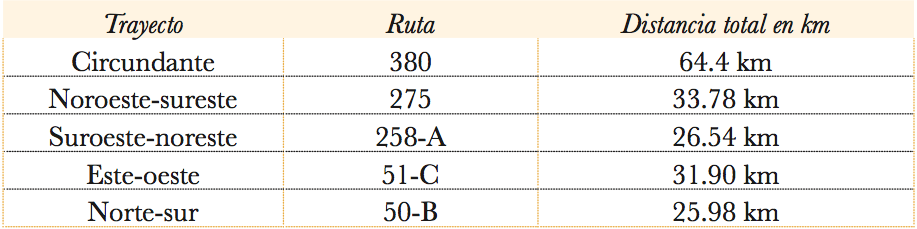

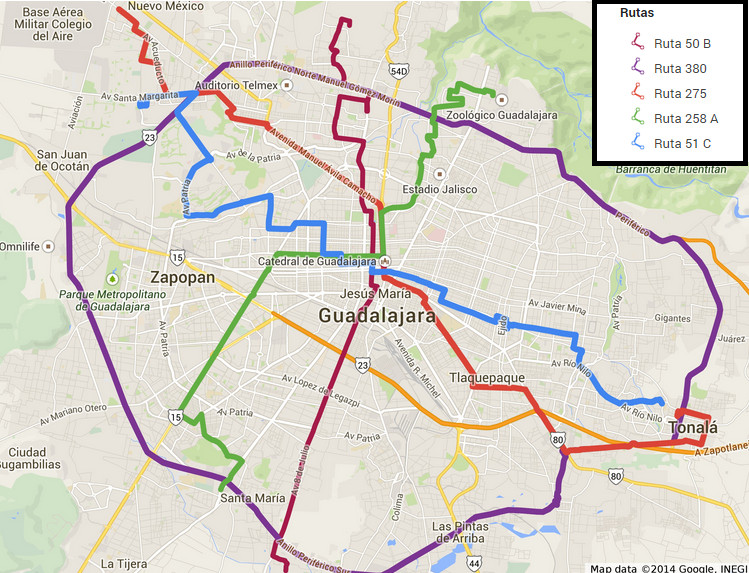

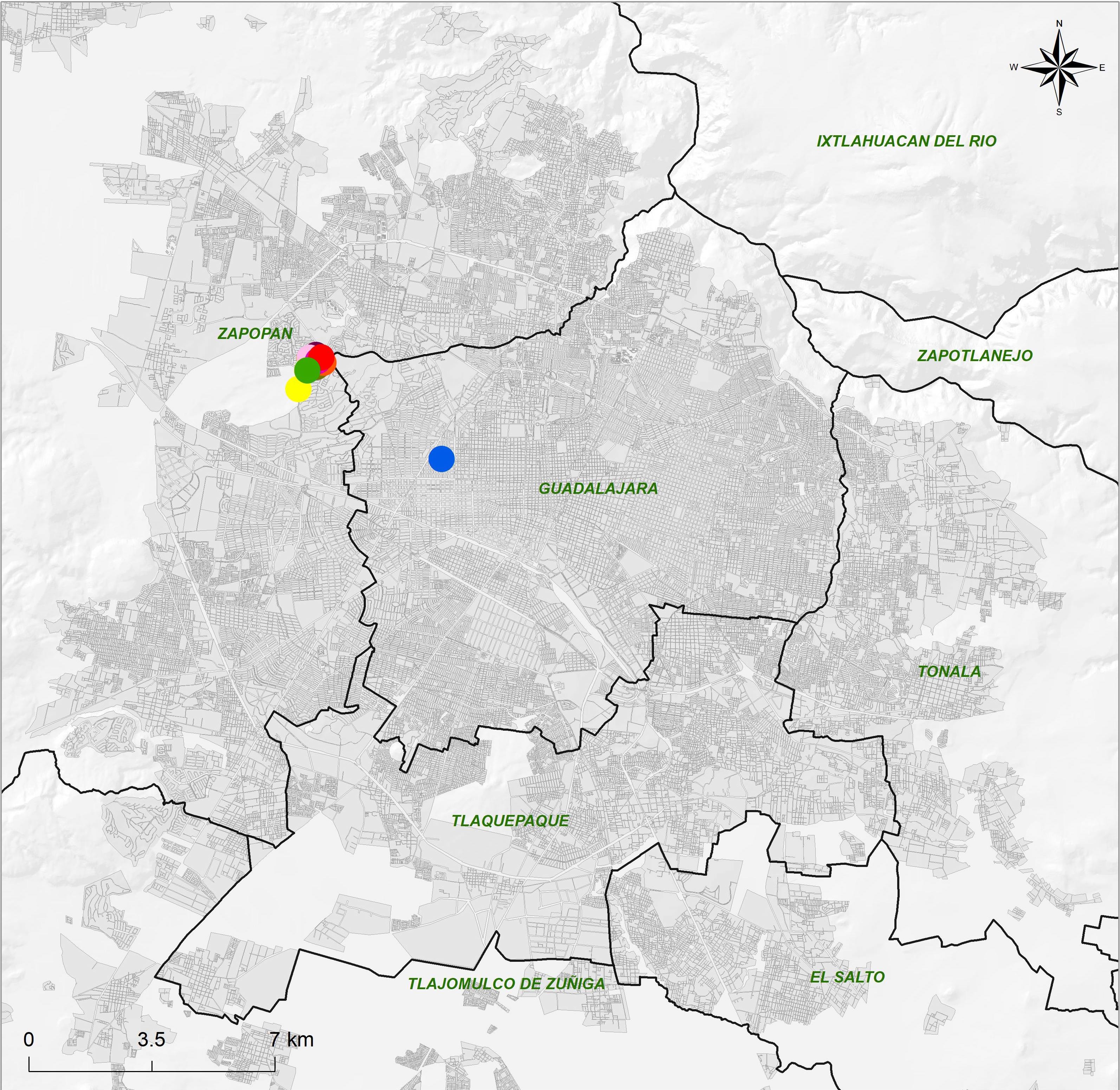

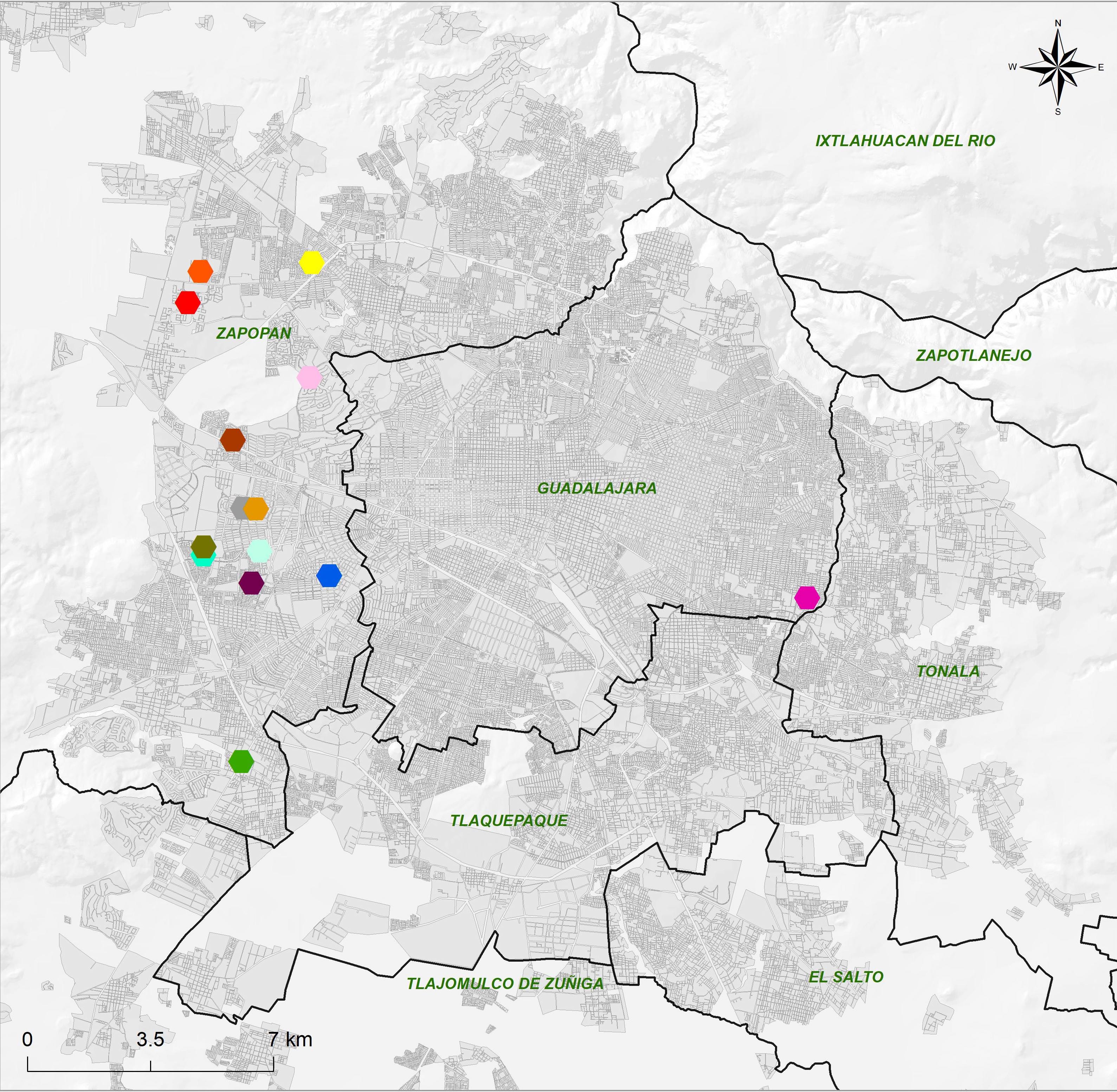

Given that the research I carried out was interested in the perception and experience of transit through the urban territory, I considered the possibility of studying in depth five public transport routes on their round trip.3 I selected routes that will travel through the various cardinal points of the city in north-south, east-west, southwest-northeast, northwest-southeast and one surrounding routes. In map 1 I present the routes that these routes follow; As will be seen, they fulfill the objective of contrasting the diversity of the city's landscapes according to its cardinal points. I sought to approach the routes at three different times and on different days of the week, so that I could identify variations in the interaction, the types of passers-by, and the conditions of the areas through which the different public transport routes circulate.

During the tours I devoted myself to observe mainly the appearance of the people (age, gender, complexion, clothing), the type of landscape (architectural facades, vegetation, roads, vehicles, bus stops, advertising) and the interactions between users (symbols , notices, implicit and explicit rules, informal talks).

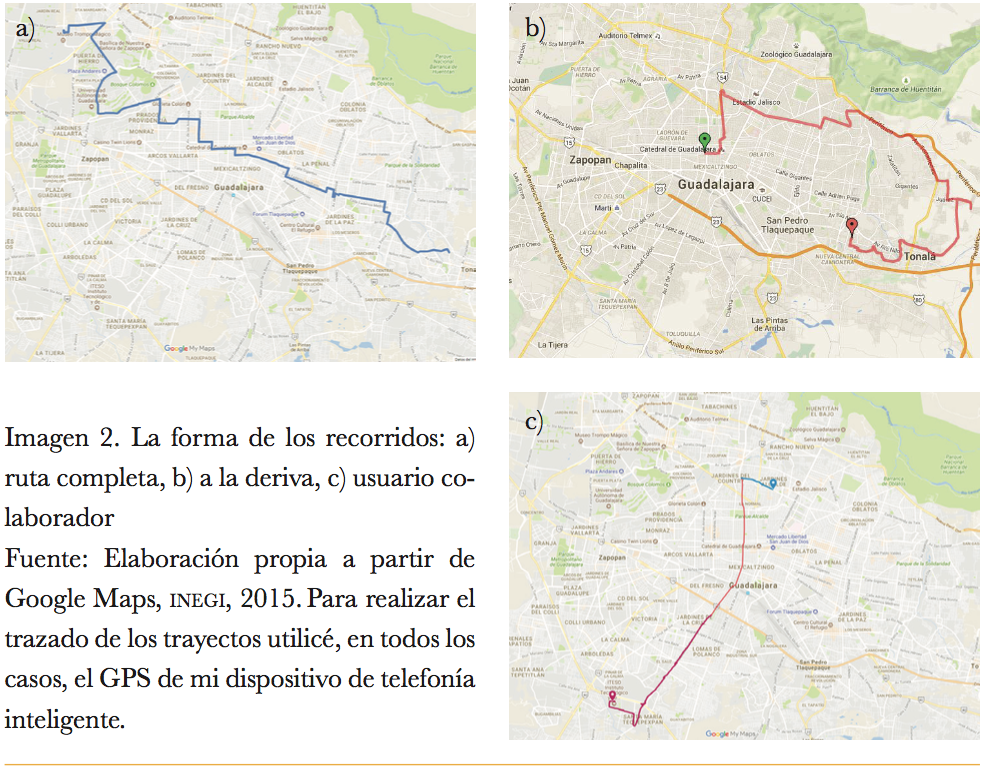

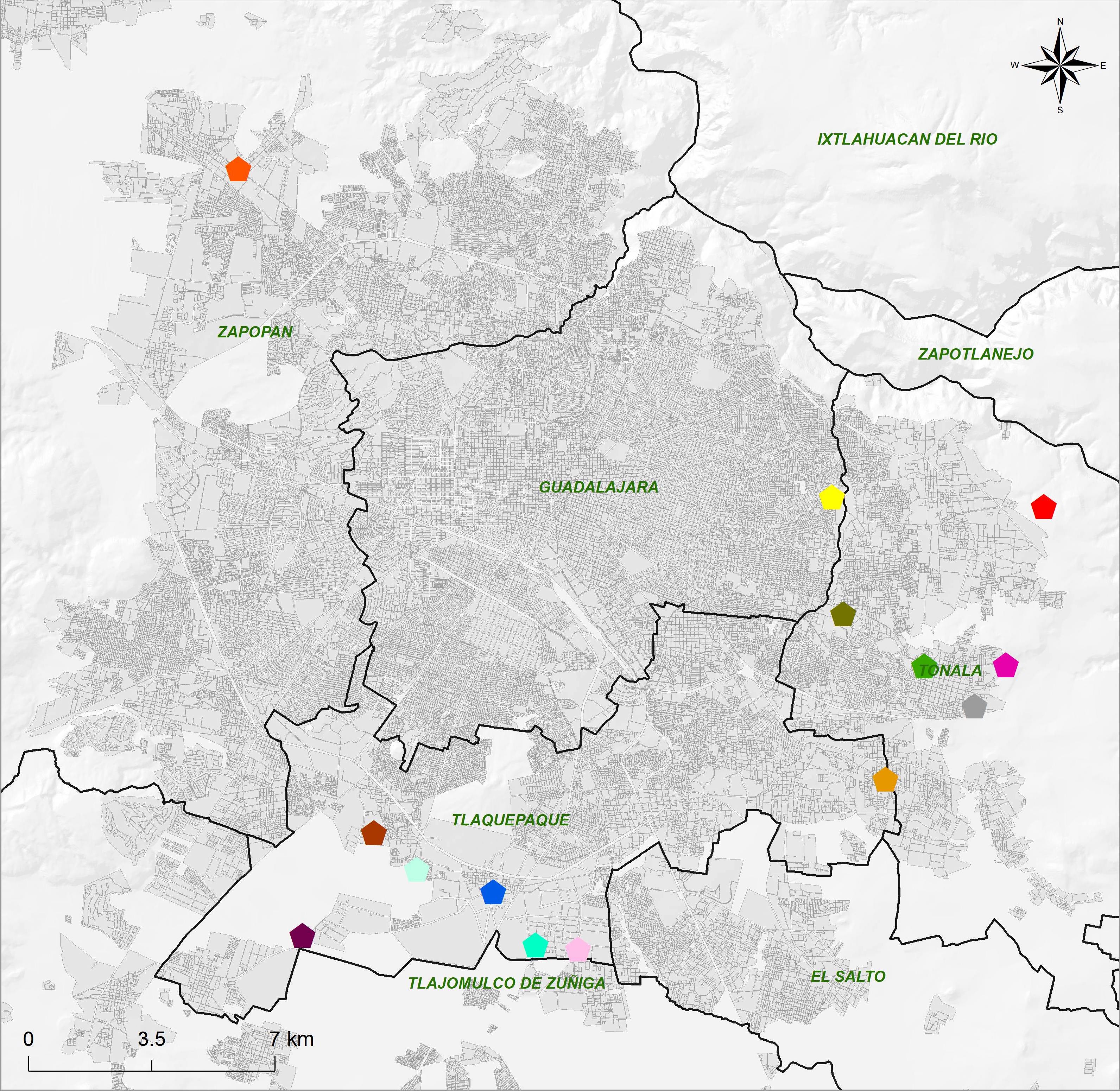

Once my observations began to reiterate what I had already appreciated in multiple tours, I decided to modify the logic under which I carried them out. Thus, I chose to continue the observation in transit, but this time under the logic of letting myself be carried away by curiosity and chance. The hazardous journeys helped me to corroborate my first appraisals and to be able to break with the limitations that traveling along a complete route imposed on me. On certain occasions, for example, I had been curious to get off at stops where many people did, to appreciate the directions to which most transshipped and what characteristics these transfer spaces had. Drifting (Pellicer, Rojas & Vivas, 2013) allowed me to satisfy that curiosity. As can be seen in image 2, the shape of the drifting routes is usually confusing and does not convey the idea of a functional route. Rather, their tracing reflects chance and curiosity.

Finally, I made three tours following the route of public transport users collaborating with the project; In these he took the opportunity to see if, in a tour carried out in a common way, he appreciated the same aspects of the interaction and the characteristics of the landscape. In addition, I took the opportunity to talk with the three people about what they considered recurring in their daily trips, the actors they used to see, the places they went through and their opinions about the service and the route in general.

Observation in transit serves to create a record of common interaction patterns and norms in the use of public transport through notes written in a field diary, supported by photographs that help to collect recurrences in the landscape and interactions. Photography, in this case, serves to create a more detailed ethnographic record and narrative, relying on the shape of the journeys as a guide to order and make sense of the experience. The day after each tour, I would sit in front of the computer to transform my telegraphic notes into a field diary. In one window of my computer I opened the map of my route, and in another my folder of photographs; At the time of writing, both the sequenced photographs and the map helped me remember elements that I had not written down in my notebook and, in a way, I re-experienced the journey.

The notes generated by these types of observations can show quite revealing recurrences and contrasts. For example, in the case of amg, the landscape contrasts enormously in the route of the same public transport route, to the extent of generating a feeling of foreigners within the city itself. The photographs taken along the route, arranged in order of succession, make it possible to identify contrasts that can be clearly associated as symbolic borders. In the images that I show below, I present one of the results that come from the collection of photographs in transit; In this case, the contrast between the architectural facades of two cardinal points other than the one can be recognized. amg.4

In an entry in my field diary I related, about my experience of traveling through the area of image 4, the following:

I would dare to say that of the routes that I have observed until today it is in this one, and in particular in this area [of the west], where I feel a greater sense of estrangement, a kind of barrier to my presence. When I look at the content of the billboards in the area, I recognize that they advertise products or establishments that do not match my lifestyle, the same happens with the luxury auto dealers that seem to be a constant commercial. The sensation is repeated when the truck passes through streets flanked by the long walls of exclusive subdivisions that are protected from the gazes of passersby. Here I feel like an intruder.

Without a notion of the route and its respective narrative, the photographs lose their meaning and become disjointed. As Ardévol and Muntañola (2004: 24) argue:

To think of photography from the gaze is to recognize that our experience, our memory and our knowledge of the world intervene in the relationship between our gaze and the image, and in this complex relationship the image provides us with new information and new knowledge.

Ardévol and Montañola complete the previous quote by saying that “thinking about the image as a gaze also pours us towards the subject, to ask ourselves how we are looked at and to recognize the gaze of the other” (2004: 24). This results in a second contribution from the observation in transit that I discovered from a technical difficulty. It was the answer to an extremely important question for me from the beginning of my research: the image that other users had of me. It all started as a result of the occasions when it was impossible for me to sit down, once on board the unit, to take notes quietly, which I solved by trying to emulate the strategies of other actors on the bus:

To take some notes I used the body posture that I have seen people who play guitar in trucks take. Feet spread, knees slightly bent, and waist leaning on the unit's seats or poles. This helped me to maintain my balance, although it did not completely solve the discomfort when writing (Christian O. Grimaldo. Field diary. Monday, May 25, 2015).

After riding routes for a while, I noticed my practice of taking notes on board the truck went unnoticed, which was very convenient for me. Later I realized that this happened because my backpack and my body postures for taking notes were very similar to those used by "checkers". These are people assigned to supervise the different routes, especially in terms of the schedules in which they circulate and the mandatory distribution of passage tickets among users. These people, in addition, usually come up with a notebook or a table in which they take notes.

It is common that when a "checker" gets on a public transport vehicle, he requests the tickets of the passage to the users, which is reflected in an anxious search of these among their belongings. It is said that, if it is not shown, the "checker" can ask the user to descend from the unit, although I have never seen this happen. After being aware of this similarity with my appearance, I realized that, on occasions, when people saw me on board, standing and taking notes, they looked for their passage ticket with that desperation of someone who does not want to be taken off the bus, I even noticed that sometimes they took the sneaky attitude of someone who did not find their ticket and does not want to be seen. My body and my appearance transmitted something unexpected by me to others, the context of the bus transformed me into a "checker" for some. Understanding that it did not go unnoticed, but rather that it was confused, led me to rethink my anthropological work.

Realizing from my own experience that, in the city, the context personifies and, above all, that only on the basis of my appearance I could pass before others for something that was not led me to question the value of records you had made. My notes were full of observations in which I assumed that certain subjects had this or that role according to their appearance, and now I realized that in many cases this would not be adapted to their concrete and individual realities. However, this made the recognition of the role played by our perceptions of others and its correlation with the urban context when traveling even more important. Would that which governs our conduct in public space cease to be real just because we do not see it all the time?

This is where returning to the ideas of Berger and Luckmann acquired a guiding sense in my research, since, in the study of interactions in the street and the conceptions of the street, it does not matter as such if the reality of the appearance corresponds with the factual reality, but the fact that this perceived reality is what orders the practices of those who perceive, giving meaning to something that could well be read as an interaction from the imaginary. The above means that the experiential experience never occurs separately from the referential and many times, it is even the second that limits the experiential experiences.

The urban order in which we live is sustained more than it seems in the urban imaginary, due to the complex and immense amount of fleeting interactions that occur on the street. To give meaning to encounters with the unknown and unexpected, people articulate an urban reality that is based on an imaginary built in the image and likeness of the urban culture in which we are socialized; at the same time, that city acquires material forms that correspond to the imaginary that we feed every day. The process is not linear, and it is precisely the confrontation of this imaginary component through the experiential experience that allows the possibility of transforming the city materially and socially; or, where appropriate, reaffirm it.

To give an intersubjective value to this strategy, observation is not enough; a dialogue with others is necessary to help articulate experiences. In this way, I took on the task of meeting other users of public transport who could share their experience with me, which led me to find different ways to record their experiences in physical, social and symbolic terms.

With the identified actors, I began to hold conversations in the form of semi-structured interviews, where I could learn more about the biography and experiences of users with different profiles. With this technique I delved into the explicit and implicit rules of interaction on buses; the recognition of places in the city and their association with what is feared or desired; the sense of belonging to certain areas; the socialization patterns typical of traveling by bus and the experience of their daily journeys.

The first conversations guided me to the development and implementation of the next part of the strategy, more focused on understanding the role that what is perceived of the city plays in the construction of typifications about the people who transit the city. In the voice of the collaborators themselves, public transport represents a way of knowing the diversity of the city. When I asked them about learning that they considered acquired from the use of public transport, responses such as the following emerged:5

Excerpt from the interview with Donato

You know places, streets, avenues, neighborhoods, that you go in the truck and you are locating to one side and another of the city. As you normally take a route and you know the whole routine more or less of that truck, then suddenly you already [change to] another job or another, if another side and that you are also getting used to taking that one, you are also recognizing different places; that sometimes you don't recognize in the cars because you always go along the almost straightest avenues that take you, and not in the truck, the truck takes you through different neighborhoods. [You see] how neighborhoods live and apart from how they look, how neighborhoods are also from different sides (Donato, 59 years old, sales agent).

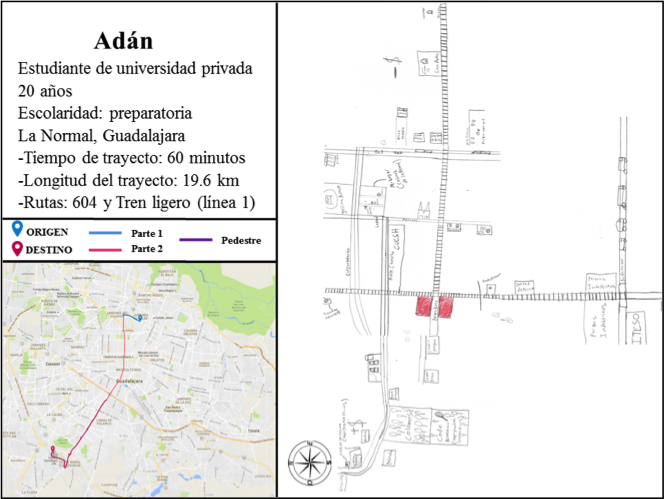

Others highlighted the use of public transport as a facilitator of the recognition of others who practice the city by the mere fact of perceiving them. Something that happens very differently in other forms of traffic, especially with the car. For Adam,

Excerpt from the interview with Adam

[Public transport] brings you closer to people, that is, if you are in a car all your life, then you will have nothing to live with other than the walls of the car, but if you move on public transport Well, even if you don't know them, even if you don't talk to them, you see them, right? and you perceive their problems, you perceive if they are angry, if they are happy, if they are in a hurry, that is, you perceive many things about them and even if they do not tell you about their life, you can get to know a little more about the people simply by getting on the a truck (Adam, 20 years old, private university student).

The correlation between the materiality of the areas and the feeling of security was an explicit mention in several of the experiences, as in Bertha's opinion when referring to an area of the city in which she feels calm:

Excerpt from the interview with Bertha

[I like the area of Providencia and Terranova], it makes me super sure, really that you can walk with the phone and that you are walking super calm, that you meet people and ... not all, but the vast majority are friendly, or that they take their dogs for a walk and so on and on a leash, so super polite. I love [I attribute it to] the infrastructure, that ... I like it too, that is, it is clean, it does not have graffiti, there is not so much garbage, I see a lot of policemen sometimes hanging around there, not very many, but it has touched to see patrols passing by. I don't know, I think I also like the part of… as people of good resources, can you say that? So how do you know that they won't do anything to you, because they don't have the need to do something to you? (Bertha, 22 years old, private university student).

Bertha herself told me about her preference for using the luxury public transport services offered by the line tur, because they generated a greater sense of security than conventional transport vehicles, mainly for two reasons: the first was that the route he used to use had security cameras on board; the second had to do with the distrust generated by what, in his perception, is about a particular type of users who do not usually use this kind of public transport, whom he described as follows:

Excerpt from the interview with Bertha

I'm going to sound bad, I never say it, but as if, people like very dark and ugly, that is, ugly, I don't know how to define it, but… ugly. And so they have ridiculous hairstyles that I had to see, they put a lot of gel here * points to his temple * oh no, horrendous !! I do not know why they do it ... but I do not know, what watery pants and I do not know, loose shirts, or when they have a cap or ... of those that have a cap and then apart they wear another cap here in the jacket (Bertha, 22 years old, student from Private university).

Even on the same route, Bertha distinguished between users who generated more trust than others, according to the zones. In his speech there were correlations between zones, appearances and sensations such as fear or security. In the area that he considered safe, he described users as follows:

Excerpt from the interview with Bertha

I almost always feel that they are like workers, so they are going to dress, I don't know, with a button down? and I don't know, with a uniform or that they smell a lot of perfume, they just had a bath (Bertha, 22 years old, private university student).

While the unsafe part of the route associated her with people of different appearance:

Excerpt from the interview with Bertha

Well, with jeans or I don't know, sweatshirts or people who I imagine clean in houses of ... like when you get to Plaza del Sol and then turn around like Obsidiana Avenue, then there are many women who get off there, they are like ladies of the toilet, I think so, I don't know, I'm not sure, a little more humble (Bertha, 22 years old, private university student).

Aurelia, another of the collaborators, shared with me her interest in knowing different areas from the ones she used to travel on her journeys; In his description appeared the curiosity to perceive the physical and interactional differences of an area that he referentially recognized as discriminatory:

Excerpt from the interview with Aurelia

I would like to know the rich areas such as Andares Palace… what is the other's name? Puerta de Hierro and those things, but as if to see how different people are or ... how they move there or how they treat me, I don't know, they say they treat those who are not from there very badly (Aurelia, 22 years old, student public university).

When I questioned Aurelia about the way she imagined those rich areas, she mentioned aesthetic attributes that characterized bodies and architectural forms alike. He distinguished the inhabitants of the area that he considered privileged even in their skin tone and pointed out: "even though they are dark, I don't know, I don't feel like they are like the dark one that I have." Which continued to reinforce the apparent nexus between what is perceived and what is imagined about certain areas of the city.

Other testimonies, such as that of Elda, an architect by profession, suggested self-reflective readings on the class condition of public transport in the amg. She recalled that the first time she used public transport, she lied to her family to be able to board it, because she had very clear restrictions for its use, especially because of the negative imagery attributed to both the service and the people who use it:

Excerpt from the interview with Elda

I come from a middle class, upper middle class family, in which… uh, they instilled in me that the truck is for the poor, right? so you can't get on a truck, because you're not poor, you know? that super strong imaginary that we have, then sometimes I lied to my mother because it shocked me that they went to school for me because it seemed like a waste of time, of money; my mother denied the traffic and well, "why are you going for me?" right? Don't complicate your life, let me take the truck back. So there was like a confrontation of ideologies in that sense, because my mother saw it as "they are going to rape you, they are going to rob you, the truck is dangerous, unwanted people get on", and so on. (Elda, 32 years old, architect).

These types of experiences and opinions led me to the next part of the methodology, more focused on deepening the connections between the form that the city acquired in its imaginary, the places where they identified perceptual borders and the relationship played by their role as passerby in the construction of such typifications, considered as anterooms for action and experiential experience.

Fourth location: the imagined city experience (the mind maps)

Once aware of the value that perception and appearances have in the senses that we give to the city and the urban, I found myself with the need to formulate a way to identify objectified forms of the urban imaginaries of other passers-by. At the same time, I needed to put into dialogue the perception that I had had about the landscape and the interactions of the users of public transport.

From the observation in transit and the semi-structured interviews, I drew a possible order in the landscape and the interactions that corresponds to certain ways of practicing and identifying oneself in the city. As Reguillo (2000: 87) maintains: “the differentiation in the perceptions and uses of time-space generates various action programs that in turn define interaction regions”, And these will, to a large extent, allow us to understand patterns of urban differentiation and segregation in a public space that is usually assumed to be homogeneous. The form we attribute to the city from our perception matters to the extent that it is directly linked to the ways in which we practice it.

The expression of the shape of the city in the conception of an individual and the collective traits that emerge from it have been highly relevant for the understanding of urban culture. The development of an analytical proposal on city images by Lynch in 1960 (Lynch, 2008) and of cognitive maps by Downs and Stea in 1970 correspond with the need to construct information on the ways in which subjects they shape the meaning of the cities they practice. In the words of Downs and Stea:

Cognitive mapping is a process composed of a series of psychological transformations through which a person acquires, encodes, stores, remembers and decodes information about the relative locations and attributes of phenomena in their daily spatial environment (Downs and Stea, 1974: 312).

Mind maps can be expressed in a number of ways, including storytelling and graphical representation; in both cases, by presenting sites and events arranged in a sequence that makes sense as it is linked by a line or path. This means that what makes cartography subjective is the act of thinking and articulating a series of connected or disconnected points on a plane (physical or mental), in order to give meaning to urban experiences or practices. The routes, the tactics, the biography, the emotional markers, the times; They all set directional coordinates and therefore the use of maps of this type allows us to externalize and objectify the processes of singularization of the city.

Mind maps incite people to endow the city with a meaningful shape, created from their experiences. To obtain these representations, I gave each collaborator a letter-size white sheet, a wooden pencil, an eraser and a pencil sharpener. I started with this slogan: “I am going to ask you to draw on this sheet a map of the city where you live, what you consider your city, and the places that you recognize best in it. You can start where you want and add whatever you want. If you need more sheets you can take the ones you need ”. Immediately, he would bring each person a small white-leaf alter and make it clear that he could take all the time he had to make it. In all cases, the maps were created in individual sessions, just in front of me.

It should not go unnoticed that, although these are representations made by individual subjects based on their perception and experience of urban life, these cartographic expressions account for patterns of internalization of the city based on the type of routes that each of the passers-by performs. Thus, mental maps give rise to generating typifications from what is shared by passers-by themselves.

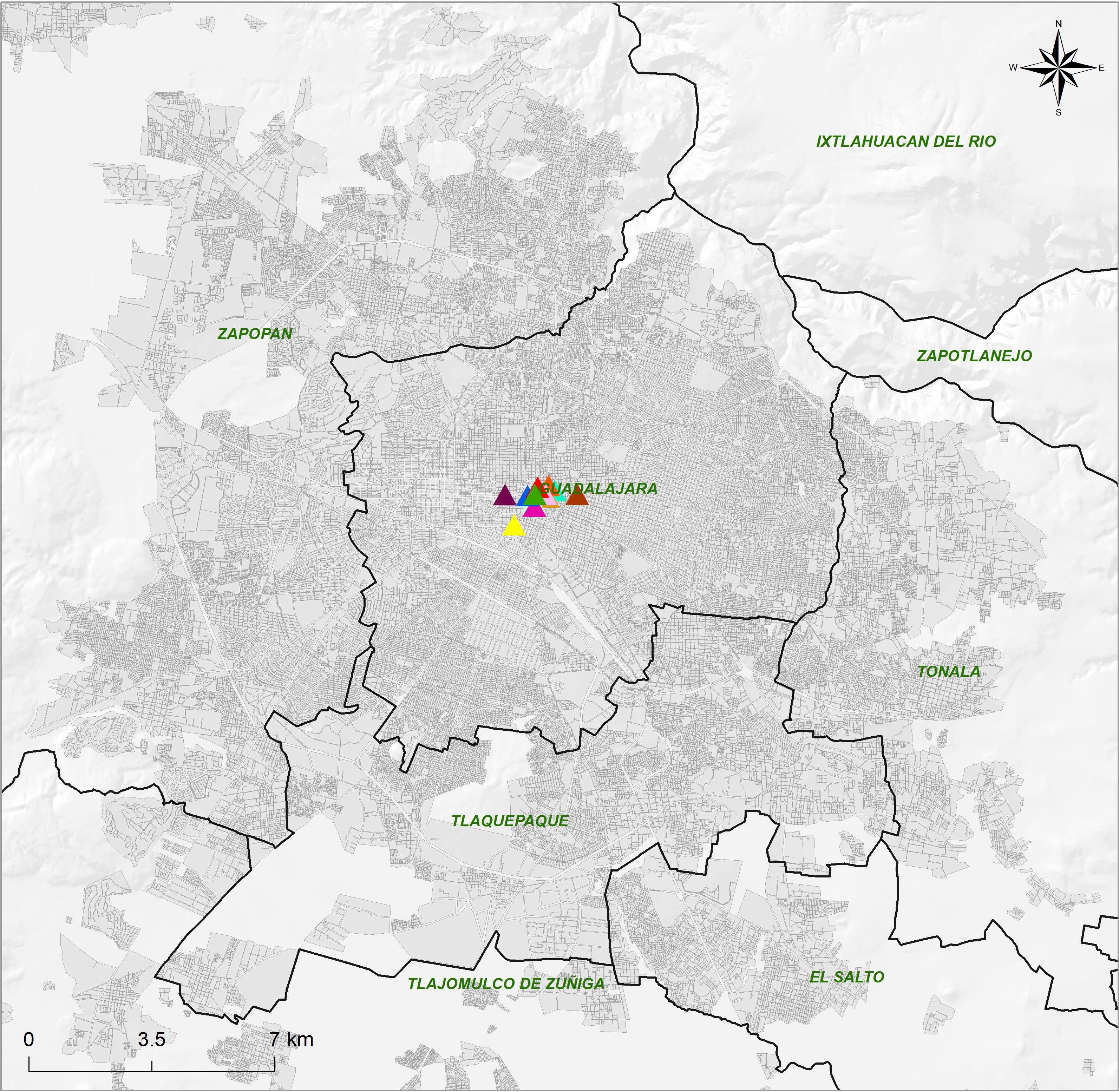

Figure 4 shows an example of the analytical value that mind maps offer. In this case, the map created by Adam, a private university student, is displayed. As can be seen, his representation of the city corresponds to the type of route he takes every day through line 1 of the light rail. In fact, in the image he produced, the city is articulated from the two existing lines of the light rail, characterized by tracks that cross the sheet vertically and horizontally. An important detail is the presence of the legend "-$" in the east and the legend "+ $" in the west of the representation. In Adam's imaginary and his narrative description, the differences captured in images 2 and 3 that I showed in the previous section are represented, which shows that the differences in the landscape have a correlate of meanings attributed to socioeconomic class markers.

In the following example I present the map created by Fausto, a bricklayer who does not have a predefined route due to his trade. His journeys last the same as the projects for which he is hired. He was the first person who explained to me why Route 380, which runs through the Periférico del amg, is associated with a high presence of bricklayers, since the surrounding route of the route allows them to reach different parts of the city by means of few transfers.6 When explaining his representation to me, he told me that, for him, “the city is like a bicycle wheel, the avenues are the spokes and the Peripheral is the rim”.

The urban form represented in the maps not only allowed me to identify conceptions of the urban fabric that corresponded with the observations in transit that I had made, but also to find parallels with my way of organizing the methodological strategy. When I saw Faust's map, I realized that the trace it presented was very similar to the strategy that I had proposed from the beginning to study the urban landscape from its different cardinal points, which can be seen on map 1 Our logic was based on a common objective: to cover most of the amg in the least number of trips possible. This makes more sense considering that the morphology of the city of Guadalajara is concentric, and 80% of the public transport routes circulate through the center of the city that both he and I practice (Caracol Urbano, 2014).

Of the 17 mental maps prepared by the collaborators, only in two was the influence of the routes on the image of the city that passersby have, but it is undoubtedly part of it. In these two cases, the collaborators only represented the area close to the neighborhood they inhabit; The reason is that it was in that fragment of the city where they felt in what they defined as their city; Above all, what made the difference with the rest of the city was that it was in that fragment where they rested from the constant traffic. This means that the experience of prolonged transit limits their notion of city to limited spaces, in which they do not experience the sensation of encountering strangeness or the unexpected. This pair of maps are the idealization of a city where the length and times of the journeys are shortened. The key point to be able to read this type of representation is, in any case, to accompany the image created with the reading of the routes and the detailed narratives of those who create them. These types of maps are a perfect pretext to start the conversation and find the intersections of experiential and referential experiences.7

One of the most illuminating details that emerged from the overall analysis of the maps was the relationship between the center and the periphery in all cases. The concentric morphology of Guadalajara, articulating the amg, sets the standard in the mental conception of each of the collaborators. The structure of the maps is articulated from the road connections between the historic center and what exists beyond it.

The role played by the Peripheral Ring is crucial to understanding the collective shape of the city. In the sense that has been presented in the mental maps, it has two main functions: road facilitator and cultural frontier. In the first case, it is a circuit that facilitates the transport of people to various places in the city. In the second, it acts as a limit between the inside and the outside of what is considered in some cases the urban setting and in others the amg.8

The representation of the Peripheral in the maps establishes a beyond Guadalajara that not only marks differences in the territory, but also in the landscape, in the services and in the subjects that inhabit-transit what exceeds this circuit. In the conception of collaborating pedestrians, living outside the Peripheral implies the need to plan more complex routes, based on greater distances, vehicles in worse conditions, in the company of people from marginalized populations. At amg, the circuit of the peripheral ring demarcates the social periphery.

In contrast to the Peripheral, which symbolizes the form of the far away, there is the center, which is a symbol of the near; together they mark in the blank space of the maps with the values of here and there, near and far. Such is the naturalness with which the center is conceived linked to the city that it not only appears in most of the maps, but in several cases they represent it in greater detail, largely based on its iconic markers. In several maps, the center is the origin of the rest of the areas that make up the collective shape of the city, a component that guides the orientation of the mental maps; a sort of compass rose of internalized space. This is extremely enlightening to understand the relationship between the experience of public transport users and the way they imagine the city, especially if we take up the fact that most public transport routes go through the center, as if it it was a service funnel. It is not for nothing that the advice is usually given that, if one day you get lost in Guadalajara, take a truck that takes you downtown and from there transfer to your respective destination.

Fifth location: the overlaps between the lived and the referenced (mapping of the imaginary)

Now that the mind maps had shown me that there were correspondences between what was seen from the observation in transit, what was heard in the interviews and what was captured in the mind maps, I felt even greater need to make visible the relationship between the experiential and referential experience of passers-by on public transport. The techniques that I have described so far give account of some indications that relate the landscapes and bodies perceived along the routes with certain socioeconomic and racial correlates, as well as with certain sensations of desire or repulsion.

Throughout my travels, I gathered a collection of 3,809 photographs; Most of them account for a collection of urban situations that show a territoriality created by my own gaze from the traffic. As I went through my photographic archive, I realized that I could remember almost exactly the geographical point where I had taken each photo, due to the exhaustive work I had done in writing my field journals, supported by the maps of my travels.

In one of my methodological readings, I found clues about the use of images for the analysis of the urban experience in relation to the various places in the city. Aguilar (2006) describes a strategy that considers the possibility of using images to evoke different places in the conception of people who travel the city. The author describes this type of images as "speaking", because their function is to incite the narration of the experience and, in turn, incite the creation of areas of meaning (Aguilar, 2006: 137).

The technique mentioned by Aguilar is an expression of what Amphoux (cited by Aguilar, 2006) called "recurrent observation technique", in which audiovisual materials are presented to city dwellers with the intention that they let their interpretations of the places from the image; According to Amphoux, this does not seek to make people speak, but rather the city (Aguilar, 2006: 136). These types of strategies seek to establish a nexus between the sensory experience and the symbolic experience of the city, which is quite enriching.

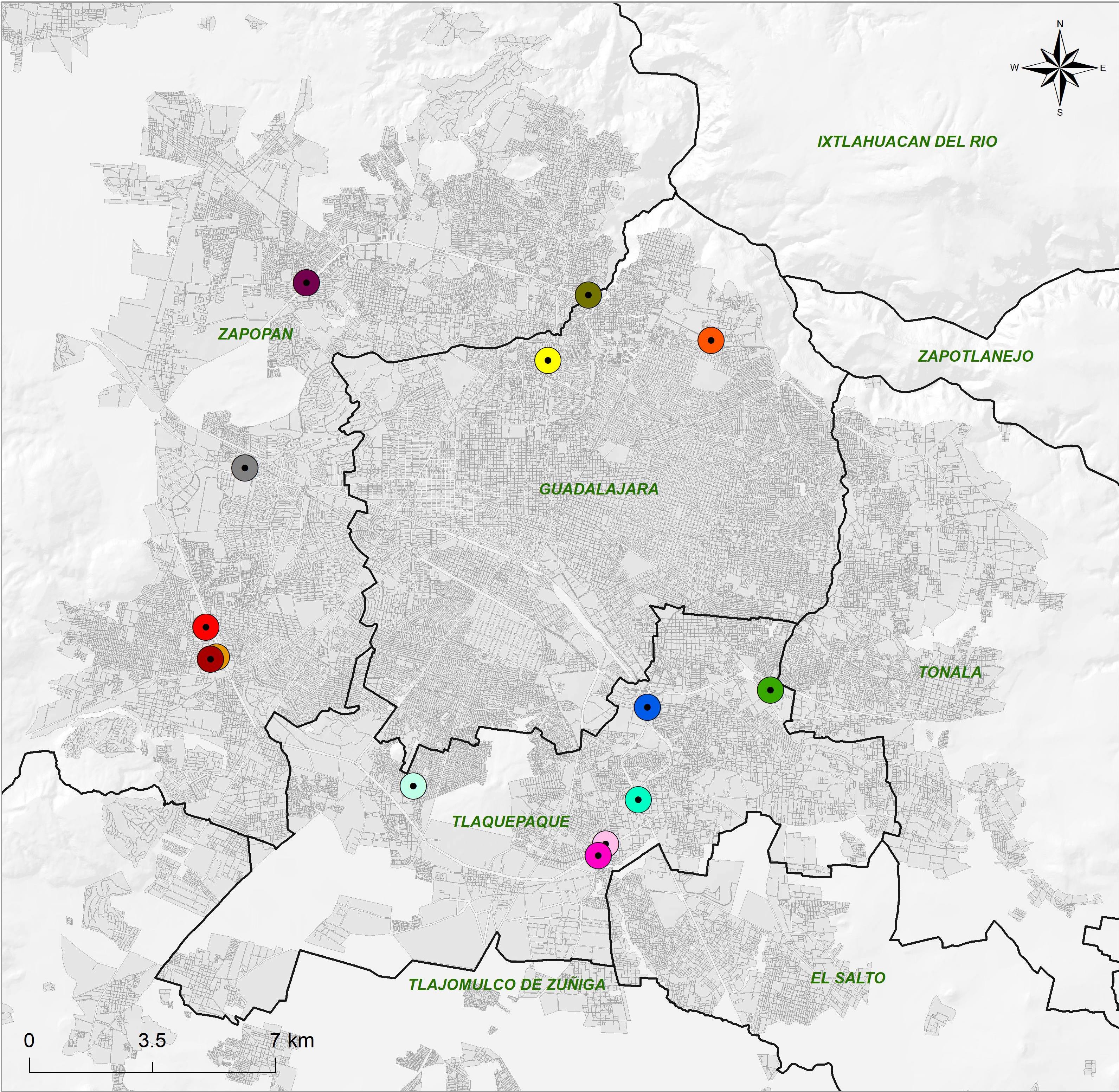

Given the familiarity I already had with the use of maps, it seemed to me that it would be a good idea to maintain the dialogue from the photograph with the other passers-by on a map, so that I could show them various urban scenes and listen to where they thought they were happening and the reasons why they placed such scenes at certain points on the map. I started from the assumption that an evocation of this type would capture in the cartographic plane a territorialized and objectified expression of the imaginary of the collaborators.

I made the selection of the photographs from different categories according to areas: commercial, residential, downtown, peripheral, services and iconic. In addition, I added a couple of places that I considered cryptic, whose architecture or context did not have elements that would make them easily located on a map. In addition to the images of places, I added two images of spectacular advertising and three images that show scenes that occurred on board different buses with no route number in sight, in the foreground of which other users of public transport appear as protagonists. In total, they added a series of 27 photographs.

Before each collaborator I spread out a cut-out plan of the amg, where he asked them to indicate their home and their work or place of study. If they had difficulty locating themselves, he helped them find points close to both sites. Then he told them that he was going to show them a series of photographs that had been taken in various locations contained within that plane, then he would show the first image and ask them to observe it carefully and to point out the point on the map where they considered that that place or that situation was. Each point was numbered in succession until the map was filled with the locations of the 27 points.9

After the participants located each photograph at a point on the map, I asked them some questions in order to find out the reasons why they had located the place of the image in a certain location and not in another. Usually, these questions were asked in the manner of a dialogue, seeking for each collaborator to detail as much as possible the reasons that made them locate each image at a certain point; Some examples of these questions were: what makes you think that it is there? Wouldn't that happen in another place? And only in that place have you seen it? Why not in another place?

Here are some examples of the results of these types of records. The photograph of point 1 shows the exclusive commercial zone located to the west of the amg known as Plaza Andares. The image captures a general plan of the area where a department store and a series of vertical buildings are located. The location that is awarded to this place is unanimous among the collaborators. That is why the map shows a series of overlapping points. An important detail is that several of the participants stated that they had never been to that place; In some cases, it was even claimed that they had not even passed that way, but they located the point exactly where it is.

Map 2. Location attributed to photograph 1

The location of point 3 shows an interesting reading about the landscapes that denote marginality in the amg. It is a site on the outskirts of the municipality of Tonalá. In the foreground, a “mototaxi” is shown, a small vehicle that has been introduced irregularly, but whose owners have been granted protection that they exhibit before the authorities to continue circulating; They operate mainly in areas where public transport service is nil or scarce and which are usually places where there are new developments, on the periphery. The reading of most of the participants began by identifying the motorcycle taxi with the periphery, which was accompanied by its association with the dirt road. The building in the background was considered by some to be an ostentatious house and by others as a party venue.

One of the most interesting details of the way in which these points are distributed is that they are associated with the east and the south of the city. In several cases it was commented that this could be in the municipality of Tlajomulco, despite the fact that it was made explicit that all the photos had been taken within the perimeter that included the map. For this reason, a good part of the points appear in the south, towards where the mentioned municipality would be. This is important if the mention of the Peripheral Ring is taken up as the border that marks the social periphery, in addition to the mention of aesthetics as a pattern that guides the geographic location of the collaborators and their areas of affiliation.

Map 3. Location attributed to photograph 3

Photo 4 shows Juárez avenue, one of the main avenues in Guadalajara near the center. The road with circulation of some cars is shown; in one corner you can see a clothing store with a long tradition, called El Nuevo Mundo. In this case, the architecture of the building that houses the aforementioned store and the cobblestones were the main reason that guided the participants to locate the place in very similar places. As in Map 1, an overlay of the points is shown. The center is highly recognizable, just like on mind maps. For the regular user of public transport, it is common to have traveled through this and other areas of the center.

Map 4. Location attributed to photograph 4

Photograph 9 shows the entrance to a private preserve located in the municipality of Zapopan, on Guadalupe Avenue. There is a perimeter surrounded by a fence and blacksmith shop; This perimeter separates the public space from the private space of those who live behind the enclosure. You can also see a security booth in the lower right corner and some parking spaces. The houses inside are two or three stories high and their facades show some common finishes and designs.

Map 5. Location attributed to photograph 9

Map 4 offers a reading that complements that of map 2. Here, the collaborators decided to locate the place based on what they consider to be the area where it would be more common to identify facades than what some define as “good taste”; or in areas where there is a higher purchasing power. A detail that stands out in the reasons why it is decided to locate the place in the west is the presence of well-preserved gardens. This area of the west appears as a representation of a type of housing inaccessible to people from the east.

Map 6. Location attributed to photograph 24

Finally, photograph 24 shows a situation that occurred in a public transport vehicle. It is a unit of Route 380, which circulates around the Peripheral Ring. I took the photograph at rush hour, around 6 pm, while the truck was traveling through the southern zone. The most impressive thing is the recurrence with which the points are distributed towards the peripheries, in addition to the constant with which the collaborators identified the vehicle as belonging to Route 380 due to the fact that the people who appear in the photograph are dark-skinned. This reaffirms the correlation between the notion of social periphery that marks the Peripheral Ring, in addition to the patterns of racial segregation associated with certain areas of the amg, in this case hand in hand with the stigma attributed to Route 380.

The examples I've shown here are just some preliminary results from an exercise that has been done with more collaborators. The intention is to show the type of relationships that are established between the image, the map and the urban imaginary of the participants. The cases that I have presented illustrate the existence of very marked recurrences in the evocations of the collaborators, who do not necessarily have a homogeneous profile; among them are men, women, professionals, graduate students, bricklayers, office workers, laborers. One of the roles that makes them more common is that of users of public transport, passers-by who perceive the city on a daily basis from journeys aboard collective vehicles.

One might well wonder what the role of being a user of public transport plays in pointing out certain points on the geographical plane, especially when I myself have pointed out that some collaborators argued that they had never passed through certain areas before putting the point in the map. What this cartographic exercise tells us is that the presence of certain actors in certain parts of the city is regulated, that is, that there are certain areas of public space in which the practice of people will be limited exclusively to traffic, due to institutionalized imaginaries that precede them. Furthermore, in some cases, if their respective bus does not pass through these areas, or they are not work points, it will be difficult to find reasons why they decide to approach. Because of the referential experiences, there will be public transport users who limit themselves to passing through certain areas and not using them, such is the case of Aurelia, who when interviewed commented on the warning not to go to Plaza Andares because they treated badly there low-income people; as well as his idea that the brown skin of those who inhabit that area is not the same as their brown skin. In cases like this, the role of user of public transport is added to other attributes of segregation, such as race and social class.

Hiernaux and Lindón (2007) highlight that an important part of what is studied under the concept of imaginaries is sustained by what Alfred Schutz considered as the concept of Wissensvorrat or “stock of knowledge”, with which he referred to the knowledge of a society that people incorporate and rethink in their lives, through the experience of their life trajectories. This incorporated knowledge forms subjective collections of knowledge, in which personal biographical experiences are integrated. As they point out, each person shares a part of their subjective heritage with the others, and in these fragments is what sustains social life, interaction and communication (Hiernaux and Lindón, 2007: 160). In this sense, the urban imaginaries involved in the mapping that I have shown here do not only account for the superficial evocation of certain places, but rather an orientation to practice, a tendency towards interaction and identification of people with the city. created from urban experience.

Conclusions

My intention when sharing the experience of configuring a methodological proposal for the study of the experience of transit through the city of other users of public transport has been to highlight that, when the study strategies completely precede the reality studied, there is a risk reaching a dead end. In anthropological terms, the urban reality is similar to a road without signs in which we need to ask for directions from others who walk along it.

At first glance, the interaction of public transport pedestrians with other actors and the urban landscape occurs in the fleeting and nondescript terms characteristic of anonymity. However, the methodology that I have proposed here shows that, behind the superficiality and transience of individual encounters, a more lasting encounter occurs: the encounter at the level of socializing structures that order the urban territory, as well as the presence and practices of people in certain areas.

On the personal scale of experience, it can be of little significance when an individual “superficially” identifies another and classifies him or her under a functional role in the public space: he is a woman, he is a man, he is young, he is an adult, he is a student, He is a bricklayer, he is a clerk; Most likely, the faces of the participants in the interaction that takes place in these terms will soon fade in the memory of the perceiver and classifier, almost at the same time that another encounter of the same type occurs. However, on the social scale of the experience, these encounters, which can be taken for superficial and fleeting, prove to be the sustenance of the most lasting order of the city; above all, because such recognitions occur in a spatialized socio-historical context. When we perceive someone when traveling through the city and we classify them according to their image within the social order in which we live every day, we are also classifying ourselves through an interplay of urban imaginaries. These superficial readings support the deeper order of modern cities and the most surprising thing is that they happen incessantly as we walk through them.

In the specific case of my study, the use of the image was presented more as a necessity than as an alternative, and this occurred because the very sense of urban reality is articulated from interactions based on the image; a type of society that, due to these characteristics, Delgado (2011: 20) recognizes as “optical”. In the strategy I have described, the image is shown both as a pen to write ethnography (Ullate, 1999) and as a stimulus to evoke and objectify the various experiences of transit through the city. It is precisely in the identification of the common between diverse experiences –in the sense that passersby attribute to the city they practice– where the main contribution of the use of the image lies; it is a dialogical potential to weave urban experiences.

The methodology that I propose makes it possible to understand the process by which passersby appropriate and reinterpret certain relatively coherent narratives based on what they experience in their daily journeys, according to territorialized units of meaning. It is from these narratives that their individual experiences when passing through the public space give the city a collective meaning.

The strategy that I have shown articulates the experience and the reference as part of the same process through which the users of public transport know and act in the daily plane of urban transit. Thus, the way in which passersby orient themselves in the geographical and social plane is visible, showing that they travel daily both through a network of road circuits and through a network of symbolic relationships that configures them as people and restricts them to certain practices and geographical points. .

The main limitation of this strategy, as I have shared it, is that it fails to show all the elements and factors that make up institutionalized imaginaries, within which most urban subjects insert ourselves when being socialized from an early age. For this, a critical and longitudinal reading of the particular history of the morphology of the city or metropolis in which the transit occurs is necessary, as well as the enunciation of the political actors who benefit from a given urban order. Otherwise, one can fall into the erroneous assumption that the urban order is woven only with the sum of experiences in the present.

Bibliography

Alyanak, Oguz et al. (1980). “Shadowing as a Methodology: Notes from Research in Strasbourg, Amsterdam, Barcelona, and Milan”, en George Gmelch, Petra Kuppinger (coord.) Urban life. Readings in the Antrhopology of the City. Long Grove: Waveland Press, pp. 89-102.

Aguilar, Miguel Ángel (2006). “Recorridos e itinerarios urbanos: de la mirada a las prácticas”, en Patricia Ramírez, Miguel Ángel Aguilar (coords). Pensar y habitar la ciudad. Afectividad, memoria y significado en el espacio urbano contemporáneo. Madrid: Anthropos.

Ardèvol, Elisenda y Nora Muntañola (2004). “Visualidad y mirada. El análisis cultural de la imagen”, en Elisenda Ardèvol, Nora Muntañola (coord.) Representación y cultura audiovisual en la sociedad contemporánea. Barcelona: uoc.

Berger, Peter y Thomas Luckmann (2006). La construcción social de la realidad. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Büscher, Monika (2006). “Vision in motion”, Environment and Planning, vol. 38, pp. 281-299.

— y J. Urry (2009). “Mobile methods an the empirical”, European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 12, núm. 1, pp. 99-116.

Caracol Urbano (2014). “Ensayo de ruta. Apuntes etnográficos de una investigación sobre transporte público en la zona metropolitana de Guadalajara (México)”, URBS Revista de Estudios Urbanos y Ciencias Sociales, vol. 5, núm. 1, pp. 147-158.

Castoriadis, Cornelius (2013). La institución imaginaria de la sociedad. México: Tusquets.

Castro, Constancio de (1997). La geografía en la vida cotidiana. De los mapas cognitivos al prejuicio regional. Barcelona: Serbal.

Corona, Sarah y O. Kaltmeier (2012) En diálogo. Metodologías horizontales en ciencias sociales y culturales. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Delgado, Manuel (2011). El espacio público como ideología. Madrid: Catarata.

Downs, Roger y David Stea (eds.) (1974). Image and environment. Cognitive maps and spatial behavior. Aldine.

Fernández, Pablo (2004). El espíritu de la calle. Psicología política de la cultura cotidiana. Barcelona: Anthropos.

García Canclini, Néstor (2007). “¿Qué son los imaginarios y cómo actúan en la ciudad?” Entrevista realizada por Alicia Lindón, 23 de febrero de 2007, Eure, vol. 33, núm.99, pp. 89-99.

Goffman, Erving (1997). La presentación de la persona en la vida cotidiana. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Grimaldo, Christian (2017). “La práctica del recorrido como construcción de sentido y territorialidad en la vida urbana”, Anuario de Espacios Urbanos. Historia, cultura y diseño, núm. 24, pp. 15-35.

Hiernaux, Daniel y A. Lindón (2007). “Imaginarios urbanos desde América Latina. Tradiciones y nuevas perspectivas”, en Imaginarios urbanos en América Latina: urbanismos ciudadanos. Barcelona: Fundación Antoni Tàpies.

Jirón, Paola y P. Mansilla (2014). “Las consecuencias del urbanismo fragmentador en la vida cotidiana de habitantes de la ciudad de Santiago”, Eure, vol. 40, núm. 121, septiembre-diciembre, pp. 5-28. Chile: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Lynch, Kevin (2008). La imagen de la ciudad. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

Morris, Jim (2004). Locals and Experts: The New Conservation Paradigm in the manu Biosphere Reserve, Peru and the Yorkshire Dales National Park, England. Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Lancaster.

Ortiz, Anna (2006). “Uso de los espacios públicos y construcción del sentido de pertenencia de sus habitantes en Barcelona”, en Alicia Lindón, Miguel Ángel Aguilar, Daniel Hiernaux (coord.), Lugares e imaginarios en la metrópolis, pp. 67-84. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana/Anthropos.

Park, Robert (1999). La ciudad y otros ensayos de ecología urbana. Barcelona: Serbal.

Pellicer, Isabel, P. Vivas-Elias y J. Rojas (2013). “La observación participante y la deriva: dos técnicas móviles para el análisis de la ciudad contemporánea. El caso de Barcelona”, Eure, vol. 39, núm. 116, pp. 119-139.

Reguillo, Rossana (2000). “La clandestina centralidad de la vida cotidiana”, en Alicia Lindón (coord.), La vida cotidiana y su espacio-temporalidad, pp. 77-93. Barcelona: Anthropos.

Sheller, Mimi y J. Urry (2006). “The New Mobilities Paradigm”, Environment and Planning, vol. 38, pp. 207-226.

Sennett, Richard (1997). Carne y piedra. El cuerpo y la ciudad en la civilización occidental. Madrid: Alianza.

Torre, Renée de la (1998). “Guadalajara vista desde la Calzada: fronteras culturales e imaginarios urbanos”, Alteridades, vol. 8, núm. 15, pp. 45-55.

Ullate, Martín (1999). “La pluma y la cámara. Reflexiones desde la práctica de la antropología visual”, en Revista de Antropología Social, núm. 8, pp. 137-158.

Vergara, Abilio (2013). Etnografía de los lugares: Una guía antropológica para estudiar su concreta complejidad. México: inah.

Wirth, Louis (1938). “Urbanism as a way of life”, The American Journal of Sociology, vol. 44, núm. 1, pp. 1-24.